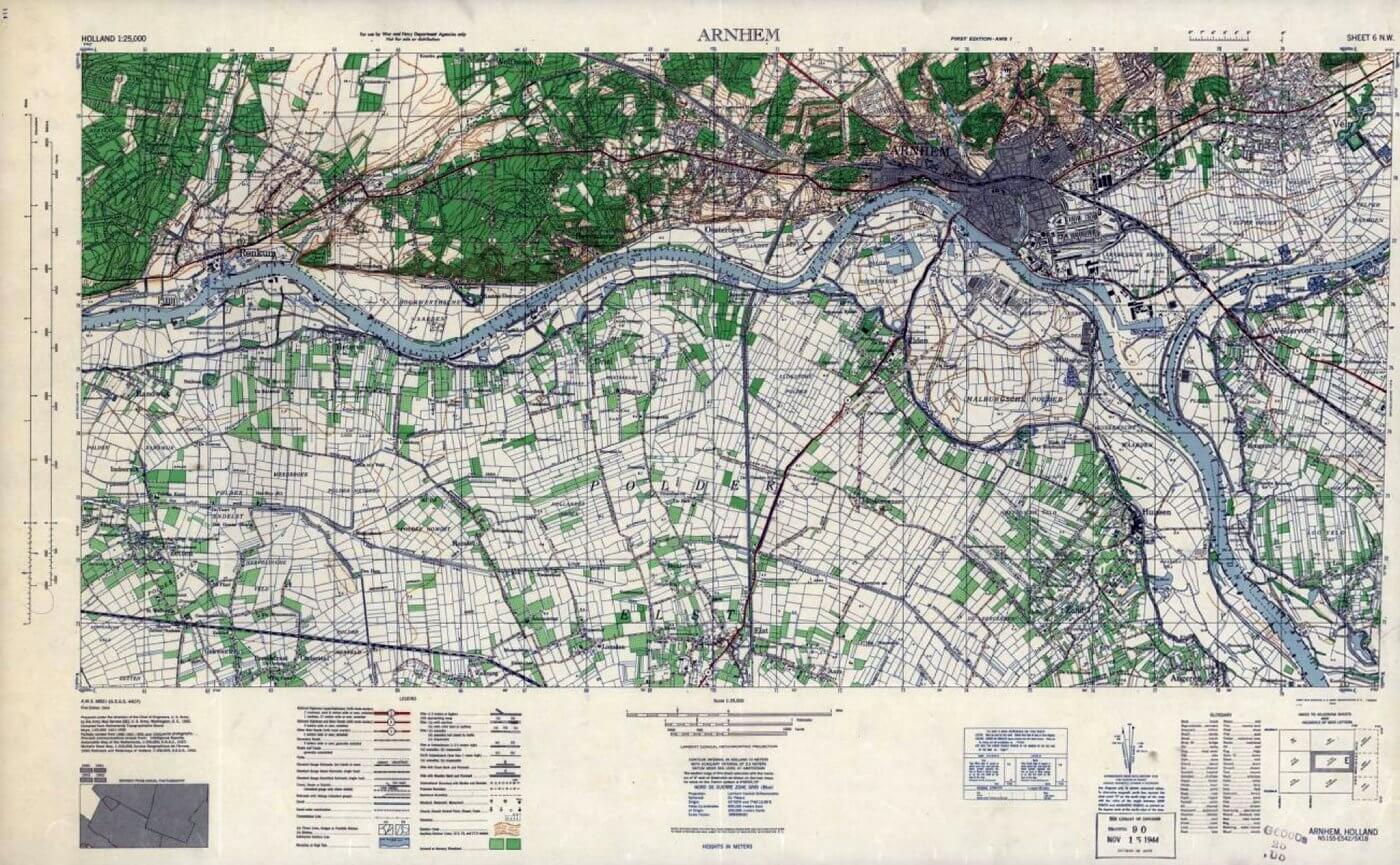

| September 17th, 1944 – September 26th, 1944 |

| Operation Market Garden |

| Objectives |

- Land at Landing- and Drop Zones at Wolfheze, Oosterbeek, and Ede.

- Capture the road bridge in Arnhem and hold it for a minimum of 48 hours

- Link up with the advancing ground forces of the 30th Corps.

| Operational Area |

Arnhem Area, The Netherlands

| Allied Forces |

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- 52nd, (Lowland) Airlanding Division

| Axis Forces |

- II SS-Panzer-Corps

- 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen”

- 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg”

- Kampfgruppe von Tettau

- Feldkommandantur 642

- SS-Unterführerschule Arnheim

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Polizei Schule

- SS-Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 4

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- SS-Wach Battalion 3

- Panzer-Kompanie 224

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 10

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 6/14

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 2

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 3

- Artillerie Regiment 184

- Sicherheit Regiment 42

- Kampfgruppe Knoche

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- MG Bataillon 30

- FlaK Abteilung 688

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Bataillon I

- Panzer Abteilung 224

- SS Ersatz Abteilung 4

- Deelen Airfield FlaK Kompanie

- Wach Kompanie

- Reichs AD

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Kampfgruppe Kraft

- SS-Panzer Grenadier Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 16

- Schwerepanzer Abteilung 506

- Schwerepanzer Kompanie Hummel

- StuG Abteilung 280

- Artillerie Regiment 191

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Werfer Abteilung 102

- Kampfgruppe Brinkmann

- Kampfgruppe Bruhn

- Kampfgruppe Harder

- Sperrverband Harzer

- MG Bataillon 47

- Marine Kampfgruppe 642

- Kampfgruppe Schörken

- Kampfgruppe Kauer

- SS-Abteilung “Landstrum Nederland”

- Kampfgruppe Knaust

- Ersatz Abteilung Bocholt

- Panzer Kompanie Mielke

- Kampfgruppe Spindler

- FlaK Abteilung Swoboda

- Kampfgruppe von Allworden

- Kampfgruppe Weber

| German Strategy Shift and Continued Resistance |

The arrival of the Polish forces at Driel forces the Germans to quickly reassess their troop deployments and tactics around Arnhem and Oosterbeek. The presence of the Poles on the southern bank of the Rhine is perceived by the Germans as a significant threat to their supply routes to Nijmegen. There is a real danger that the 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg” could become cut off from the 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen” on the northern bank, or worse, that the Poles might attempt to seize Arnhem Bridge from the south.

In response to this threat, as well as the advancing XXX Corps to the south, the Germans establish Sperrverband Harzer, a blocking line south of the Rhine, to contain the Polish forces. This defensive formation ties up around 2,400 German troops—forces that could have otherwise been used in the ongoing battle in Oosterbeek. The creation of Sperrverband Harzer serves as a crucial diversion for the Allies, limiting the reinforcements available to the Germans fighting on the northern bank.

Recognising that the previous day’s infantry and armour assaults on the 1st Airborne Division have yielded little success and caused significant casualties, the Germans shift their tactics. Rather than attempting to overrun the Oosterbeek perimeter outright, they focus on containing the British forces within their defensive pocket, subjecting them to relentless artillery bombardment. By the end of the battle, the Germans have positioned 110 artillery pieces of various types around Oosterbeek, ensuring they are well-supplied with ammunition. Throughout the day and the remaining days of the battle, the German strategy focuses heavily on artillery. Their infantry assaults become more methodical and calculated, using artillery and mortar bombardments to isolate individual buildings or sections of wood before launching infantry attacks supported by tanks. The goal is to gradually drive the British out of key positions, taking control of small, specific areas. Despite the Germans’ superior numbers and firepower, their progress is limited. The British forces hold their ground, inflicting heavy casualties on the attackers during each assault.

The 1st Airborne Division, unable to counter this heavy bombardment effectively, resorts to digging deeper into their slit trenches and fortifying their positions to minimize casualties from the constant shelling. The psychological toll of this bombardment is severe, particularly on those who have had little or no sleep for days, leading to cases of shell shock among the troops.

The battle intensifies along the riverbank as Kampfgruppe Spindler launches another determined assault on the British defenses. These armoured attacks pose a significant threat, particularly as the 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen” pushes from the east towards the British gun batteries and Oosterbeek Church, aiming to cut off the British forces from their river crossing. To the west, the von Tettau division continues to hold the high ground at Westerbouwing and probes the British defences, though many of their units are cobbled together from training groups, troops on leave, and even naval and Luftwaffe personnel with minimal infantry training.

The hastily assembled nature of some German units limits their effectiveness, especially in urban combat. These less-experienced troops struggle against the well-trained and battle-hardened British airborne soldiers and often hesitate to push too deeply into the fierce fighting around Oosterbeek. However, the veteran troops of the 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen”, experienced in urban warfare, continue to press the British eastern flank with a mix of infantry and Panzer support, creating a constant threat to the perimeter’s defenses.

The German Panzer units, which had performed so effectively at Arnhem Bridge, find the terrain in Oosterbeek much less favorable. The British 1st Airlanding Brigade has had time to position its anti-tank guns strategically in key defensive points, where the urban environment creates ideal conditions for ambushing tanks. This forces the German armour to proceed cautiously, as any aggressive movement risks encountering well-placed British anti-tank fire. Additionally, the British tank-hunters, using PIAT’s, take advantage of the close-quarters fighting, stalking Panzers and targeting them at short range. Panzer crews, often confined inside their vehicles, are particularly vulnerable to these ambushes, paying a heavy toll in the urban battleground of Oosterbeek.

In addition to the artillery barrage, German snipers pose a constant threat. These snipers are not only positioned on the front lines but also infiltrate deep into British territory, taking advantage of the cover provided by the woodland in the southern half of the perimeter. Members of the Glider Pilot Regiment, who are part of the Division’s reserve and frequently patrol the gaps in the British defences at night, take on the task of hunting down these snipers, a role in which they become highly effective.

| Defending the Perimeter |

In the early hours of Friday morning, at approximately 04:00 hours, around 160 pathfinders from the 21st Independent Parachute Company, under Major Wilson, are redeployed to reinforce the Oosterbeek perimeter. They establish defensive positions in houses and gardens along Pietersbergseweg and Sandersweg, taking over from the worn-out remnants of the 10th Parachute Battalion, who had been holding the line at Utrechtseweg. Another unexpected group, the 250th (Airborne) Light Composite Company, Royal Army Service Corps, commanded by Captain John Cranmer-Byng, is also moved to the front lines. Normally a supply unit, they now occupy defensive positions along the track junction at Bildersweg and van Deldenpad, extending to the road junction of Pietersbergseweg and Sandersweg. Both units are instructed to hold their positions and advance if the opportunity presents itself.

As Brigadier Hackett visits his troops that morning, he is informed of escalating German infiltration within the British perimeter. The sniper threat has worsened significantly, with German snipers infiltrating the area, not only near the front line but also deeper inside British-held positions. In particular, the parkland to the south offers ideal cover for these snipers, who are causing multiple casualties. A German sniper even uses the rear of the Hartenstein Hotel as a vantage point, further intensifying the danger.

To counter the sniper threat, the Glider Pilot Regiment is tasked with anti-sniper patrols. Previously engaged in night patrols, the glider pilots now also operate in daylight, forming small eight-man teams that split into pairs to hunt down snipers. These teams quickly become effective in neutralising the threat.

Around the afternoon headquarters recieves the follwing message: “43 Division attacking main bridge, Arnhem on a two Brigade front, 1000 hours. 2nd Household Cavalry contacted Polish Parachute Brigade.” This news, along with the hope that the British perimeter on the northern bank could hold for another twenty-four hours, raised expectations that relief was possible. British artillery was firing overhead, and there was a sense that success was still within reach.

Under the cover of early morning mist, two troops of armoured cars from the Household Cavalry had advanced and made contact with the Polish forces stationed outside Driel. The presence of these elements from the Guards Armoured Division on the southern bank indicated that XXX Corps might soon be within range of supporting the beleaguered 1st British Airborne Division. If the Polish troops could continue to hold Driel and secure the ferry crossing, reinforcements might reach the northern bank.

However, the situation on the north bank remained precarious. Although British forces controlled some areas, the loss of the Westerbouwing hill and other key positions to the Germans posed a significant challenge. The depleted British units were unlikely to have enough strength left to dislodge the Germans from the high ground or regain control of the riverbank. Control of these areas was crucial for any successful river crossing and potential reinforcement efforts.

As the day progresses, the Glider Pilot Regiment units defending Stationsweg face mounting pressure. German forces, equipped with self-propelled guns, begin to target British defensive positions, focusing their fire on the houses occupied by the glider pilots. Sergeant Louis Hagen of D Squadron describes how a German self-propelled gun moves into position at a nearby crossroads. The gun’s loud engine revs can be heard before it opens fire, sending shells that tear through the brick walls of houses occupied by British troops. These guns repeatedly strike the buildings, attempting to weaken the defences.

Throughout the day, German tanks and self-propelled guns continue their attacks, methodically shelling British positions along Stationsweg. Supporting German infantry follow these bombardments, attempting to breach the British defenses by exploiting the damage to the buildings. However, despite these efforts, the British hold their ground, though at a heavy cost in casualties.

Meanwhile, Staff Sergeant Arnold Baldwin of B Squadron, who has been stationed near the Hotel Hartenstein with Captain Angus Low and 20 Flight, is reassigned to support the 21st Independent Parachute Company. Baldwin and his team are tasked with defending a house near the Schoonoord Hotel, now being used as a hospital. Upon arrival, Baldwin is informed by the wounded commanding officer that they are to hold the building and remain on high alert for potential German attacks.

That evening, at 22:00 hours, the divisional perimeter is reduced in the north-west due to increasing pressure from German forces. As part of this reorganisation, E Squadron of the Glider Pilot Regiment moves from its position in the woods to the left flank of F Squadron, taking up a defensive line at the corner of Hartensteinlaan and Oranjeweg. This adjustment allows the two squadrons to once again fight side by side. E Squadron links up with A Company of the 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment on its left flank, while F Squadron’s right is secured by the 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers stationed at Paul Krugerstraat.

The unrelenting German shelling and mortar fire throughout the day force the Airlanding Brigade to relocate its headquarters to a more concealed position in the woods of the Hemelsche Berg estate, out of sight of German artillery observers. The brigade’s reserve, C Squadron Glider Pilot Regiment, now holds defensive positions stretching from the Kneppelhout monument to a house on the Hemelsche Berg estate. Two 6-pounder anti-tank guns from the 2nd Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment are integrated into their defence, providing additional firepower against potential German armor.

Sergeant Norman Ramsden of 17 Flight, A Squadron, is positioned west of divisional headquarters when his unit is called to conduct a patrol. However, before they can depart, they come under a heavy German mortar barrage. With casualties mounting, the patrol is called off, and Ramsden’s group returns to their original positions.

Later that evening, preparations are made to receive reinforcements from the Polish Parachute Brigade, expected to cross the Rhine under cover of darkness. Selected glider pilots are assigned to guide the Polish troops to their positions within the British perimeter. Captain Harry Brown of the 4th Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, is given command of the ferrying operation, which aims to bring approximately 200 Polish soldiers across the river. Staff Sergeant Fred Ponsford of A Squadron is one of the guides tasked with leading the Poles through enemy lines and into the British defences.

Upon reaching the Rhine, the guides wait in silence, knowing that the Germans are just 40 metres away. Despite hearing Polish boats passing on the river, the proximity of enemy forces makes communication impossible. After what feels like an eternity, the Polish troops begin to land, and Ponsford and the other guides successfully lead them to their designated positions in Oosterbeek.

Despite the bravery of the Polish forces and the determined efforts of Captain Brown and his exhausted troops, only fifty-five Polish soldiers successfully cross the Rhine to reinforce the British perimeter. To have any real chance of linking up with XXX Corps and establishing a bridgehead on the Rhine, a much larger number of Poles would need to attempt the perilous crossing. However, the resources required to support further crossings are limited, and supplies within the British-held perimeter are rapidly running out. Both ammunition and food are in short supply, and hunger is starting to take its toll on the defenders.

There is, however, a moment of hope on the south bank. As the Polish troops prepare for their next crossing attempt, an armoured column approaches their lines at high speed. Initially, the lead tank hits a Polish anti-tank mine, leading to a brief exchange of fire. Soon after, the true identity of the column becomes clear, it is a British force. The column consists of infantry from the 5th Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, and tanks from the 4/7th Dragoon Guards, both part of the 214th Infantry Brigade. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Taylor, the infantry ride on the rear decks of the tanks, completing a daring 16-kilometre journey to Driel, a manoeuvre that becomes known as the ‘Driel Dash.’ Despite this impressive feat, the newly arrived forces are unable to directly influence the battle. Without boats, they can do little except wait for the rest of their brigade and the 43rd (Wessex) Division to arrive at Driel.

Meanwhile, the situation south of Driel remains precarious. The narrow corridor along which XXX Corps is advancing, designated as “Route Club” but known to the troops as “Hell’s Highway,” is under constant attack from German forces on both sides. Aware of the vulnerability of the Allied supply line between Nijmegen and Arnhem, German forces continually attempt to sever the route. With fighting still fierce to the south and German strength around Oosterbeek increasing by the hour, the possibility of a successful river crossing to reinforce the British perimeter appears increasingly unlikely.

| Royal Air Force Resupply Missions |

The Royal Air Force does not conduct a resupply mission, as it is believed that XXX Corps will link up with the Division within hours, making further reinforcement unnecessary. This pause allows aircrews to rest and gives mechanics time to repair their damaged aircraft.

| Contacting XX Corps |

Ordered by Major General Urquhart, Lieutenant Colonel Mackenzie and Lieutenant Colonel Myers cross the River Rhine in a rubber boat, joining up with the Polish Brigade on the far side. They arrive under intense enemy fire, aimed at preventing the Poles from advancing towards the Arnhem road bridge, a move that was never part of the original plan. Just before the two officers reach Driel, a critical development occurs: the first direct contact between XXX Corps and the airborne troops. Three Daimler Dingo scout cars from the Household Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant R. Wrottesley, navigate through country lanes and reach Driel. This route bypasses the main road north from the Nijmegen bridge, where the 10. SS-Panzerdivision has blocked the advance of the Guards Armoured Division and the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division at Elst.

Upon arriving in Driel, Mackenzie and Myers use the radios in the Household Cavalry’s armoured cars to establish contact with Lieutenant General Horrocks at XXX Corps Headquarters. They relay Urquhart’s urgent message, stressing that without immediate reinforcements and supplies that night, the airborne division’s position will become untenable. Horrocks, recognising the gravity of the situation, commits to sending units from the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division to the Rhine with amphibious DUKWs as a matter of urgency. However, a new challenge arises as the route to Driel is once again cut off by enemy forces, complicating the task further.

| Polish Preperations for the First River Crossing |

Stanislaw Sosabowski and his Polish forces stationed at Driel have no intention of pursuing the actions expected by the Germans. However, the Germans remain unaware of this and continue to anticipate a potential breakout or an attempt by the Poles to seize Arnhem Bridge. Instead, the Polish forces hold their ground, staying in position as they quietly prepare boats for a river crossing, all while waiting for nightfall out of sight of the enemy.

To counter the perceived threat on the southern bank, the Germans launch a series of heavy attacks throughout the day. Mortar bombardments and coordinated infantry assaults, supported by Panzers, target the Polish defenders. Despite the intensity of the attacks, the Poles maintain a determined defense, though they are eventually forced to retreat from some of their outer positions around Driel. By the end of the day, neither side gains a decisive advantage, but the Poles successfully hold onto the village as darkness falls.

Besides the Germans attacks, the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade is confronted with another daunting task: crossing the Rhine River to reinforce the 1st Airborne Division, which is under intense pressure from German forces. The original plan had counted on the Polish Brigade landing once the Arnhem bridge was secured, allowing them to link up with the Airborne Division and launch a coordinated assault. After contacting XXX Corps, Lieutenant Colonel Mackenzie approaches Sosabowski with urgent orders from Major General Urquhart, stressing the immediate need to ferry Polish troops across the river to reinforce the perimeter’s defences before they are overrun. “Even a few men could make the difference,” Mackenzie insists, noting that several two-man rubber dinghies from the airborne forces could be used for the crossing. Sosabowski agrees and plans to begin the operation at nightfall, hoping that the DUKWs from the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division might arrive in time to assist.

Meanwhile, the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division is encountering significant challenges. The 129th Infantry Brigade is advancing along the Nijmegen–Arnhem road with the Guards Division, while the 214th Infantry Brigade attempts to push forward along minor roads to the west. Both brigades face stiff resistance from well-equipped German forces supported by armour, making progress slow and requiring carefully coordinated attacks.

To overcome these obstacles, Brigadier Essame, commanding the 214th Infantry Brigade, dispatches a flying column from Lieutenant Colonel Taylor’s 5th Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, along side roads to reach the river. The column includes two DUKW’s loaded with supplies, intended to ferry Sosabowski’s brigade across.

Taylor’s group faces a hazardous journey but eventually reaches the river after dealing with two Tiger tanks. With the DUKW’s now at Driel, there is finally a way to transport Sosabowski’s brigade across the river. However, locating a suitable launching site proves difficult. Compounding the issue, rain begins to fall, turning the ground into mud and immobilising the heavy vehicles. Despite strenuous efforts to move them towards the river, the DUKW’s slide into ditches and become hopelessly bogged down, rendering them unusable.

With the DUKW’s out of action, the Poles are left with no choice but to use the rubber dinghies provided by the 1st Airborne Division, ferrying two men at a time across the 400-metre-wide river.

| 1st Airborne Division’s Preperations for the First River Crossing |

As the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade is making its plans to cross the river, Captain Harry Faulkner-Brown of the 4th Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers is given a critical mission: to ferry Polish soldiers across the river using inflatable dinghies. The operation is fraught with difficulties from the outset. The river’s strong current, coupled with intense enemy artillery fire, makes the crossing perilous. The limited number of dinghies available, small, two-man recce boats, adds to the challenges, as each trip can only transport a single soldier at a time.

In the early afternoon, Captain Faulkner-Brown sets out to retrieve the dinghies from a location south of the Hartenstein Hotel, where the lightly wounded are being sheltered. He manages to gather six recce boats and one large dinghy from the Royal Air Force, possibly salvaged from a downed aircraft. Despite the grim circumstances, there is a brief moment of camaraderie when a padre offers Faulkner-Brown a cup of tea. However, this brief respite is shattered when a mortar bomb explodes nearby, fatally wounding the padre and starkly reminding everyone of the constant danger they face.

As night falls, the situation becomes even more critical. Faulkner-Brown selects twelve sappers to assist in the ferrying operation. They load the dinghies, along with essential equipment such as tracing tapes, signal cables, and a wireless set connected to Divisional Headquarters, onto two jeeps and head out to the riverbank. The journey is tense, as the group must navigate through the dark, rain-soaked terrain, moving cautiously to avoid detection.

| First Polish River Crossing |

Upon reaching the river, they find a suitable location for the crossing, a shoreline sheltered by stone groynes that extend about 45 metres into the water. The area is ideal for loading and unloading the dinghies, but the operation remains incredibly dangerous. As they prepare to launch the first dinghies, British Lieutenant Maclean of the Glider Pilot Regiment approaches Captain Zwolanski of the Polish Advanced Liaison Party to discuss the night crossing. Despite the risks, Maclean and his fellow glider pilots volunteer to assist in the operation, demonstrating their determination to help their beleaguered comrades.

Captain Zwolanski and Lieutenant Maclean work together to plan the crossing, establishing posts along the riverbank and mapping out the route through the meadow to the Division’s positions. As they set out, they encounter heavy artillery fire, the sound of shells passing overhead louder than anything they have experienced before in Arnhem. The intensity of the bombardment is unnerving, as the soldiers know that a single direct hit could cause catastrophic damage, especially with the Hartenstein Hotel and their trenches vulnerable to heavy artillery.

As the operation begins, Captain Faulkner-Brown sets up a defensive position on the shore and rows across the Rhine to establish contact with the Polish forces on the other side. Upon arrival, he is greeted by a group of Polish soldiers who are eager to cross but report that they are under heavy fire. Despite the difficult conditions, the soldiers are determined to push forward, aware of the critical role they play in the ongoing battle.

However, the crossing proves to be more challenging than anticipated. The strong current of the Rhine snaps the signal cables meant to guide the dinghies, forcing Faulkner-Brown and his men to rely on manual rowing. Each dinghy can only carry one soldier at a time, significantly slowing down the operation. Meanwhile, the Polish troops on the south bank continue to face intense ground fire, adding to the difficulties of coordinating the crossing.

As the night wears on, the situation becomes increasingly dire. Captain Mackowiak, leading the Polish Advanced Liaison Party, guides his men through the riverside meadow, which has now become “No Man’s Land.” The burning suburbs of Arnhem and the village of Driel on the opposite bank illuminate the night, casting an eerie red glow over the landscape. The group moves cautiously, aware that any misstep could expose them to enemy fire.

Upon reaching the riverbank, they take cover behind a stone embankment, observing German machine-gun positions on either side. Captain Mackowiak instructs his men to remain hidden and silent, ensuring that the Polish troops crossing the river can do so undetected. Despite the heavy artillery fire and the challenges posed by the burning landscape, the first dinghy manages to reach the shore, delivering six Polish soldiers.

Lieutenant David Storrs, a Field Engineer from the Commander of Royal Engineers, joins the operation with remarkable determination. Over the course of the night, he rows back and forth across the river 23 times, ferrying one Polish soldier on each trip. However, despite the best efforts of everyone involved, only 40 to 50 Polish soldiers successfully cross the river. The operation’s slow pace frustrates the Polish liaison officer, leading to tensions with Captain Faulkner-Brown, who eventually orders the officer to leave.

As more Polish soldiers arrive on the northern bank of the Rhine, they move quietly along the embankment, making their way back to the meadow. The rain intensifies, providing some cover from enemy fire, but the conditions remain harsh. The soldiers, though tired and cold, gather with a sense of purpose, knowing that their reinforcement is crucial to the ongoing battle.

The group eventually reaches the artillery positions, where they are directed to a nearby church to await further orders. Inside the darkened church, the flames from the distant fires cast a crimson glow through the windows, illuminating the high altar. The atmosphere is tense yet focused, as the soldiers prepare for the next phase of their mission.

By 04:00 on Saturday morning, the ferrying operation is halted, likely due to the exhaustion of the men and increased German interference. While accounting for his troops near the church, Captain Faulkner-Brown realises that Lance Corporal Flannery is still on the south bank. Determined to bring him back safely, Faulkner-Brown and another sapper row across the river one last time, successfully retrieving Flannery without incident.

As said earlier, only 55 Polish soldiers manage to cross the river that night, a number far too small to make a significant impact on the battle. The limited reinforcements underscore the challenges faced by the Allied forces, who are struggling to hold their ground against a relentless enemy. Despite the bravery and determination shown by all involved, the operation highlights the overwhelming difficulties and the precariousness of the situation as the battle for Arnhem continues.

| Multimedia |