| September 17th, 1944 – September 26th, 1944 |

| Operation Market Garden |

| Objectives |

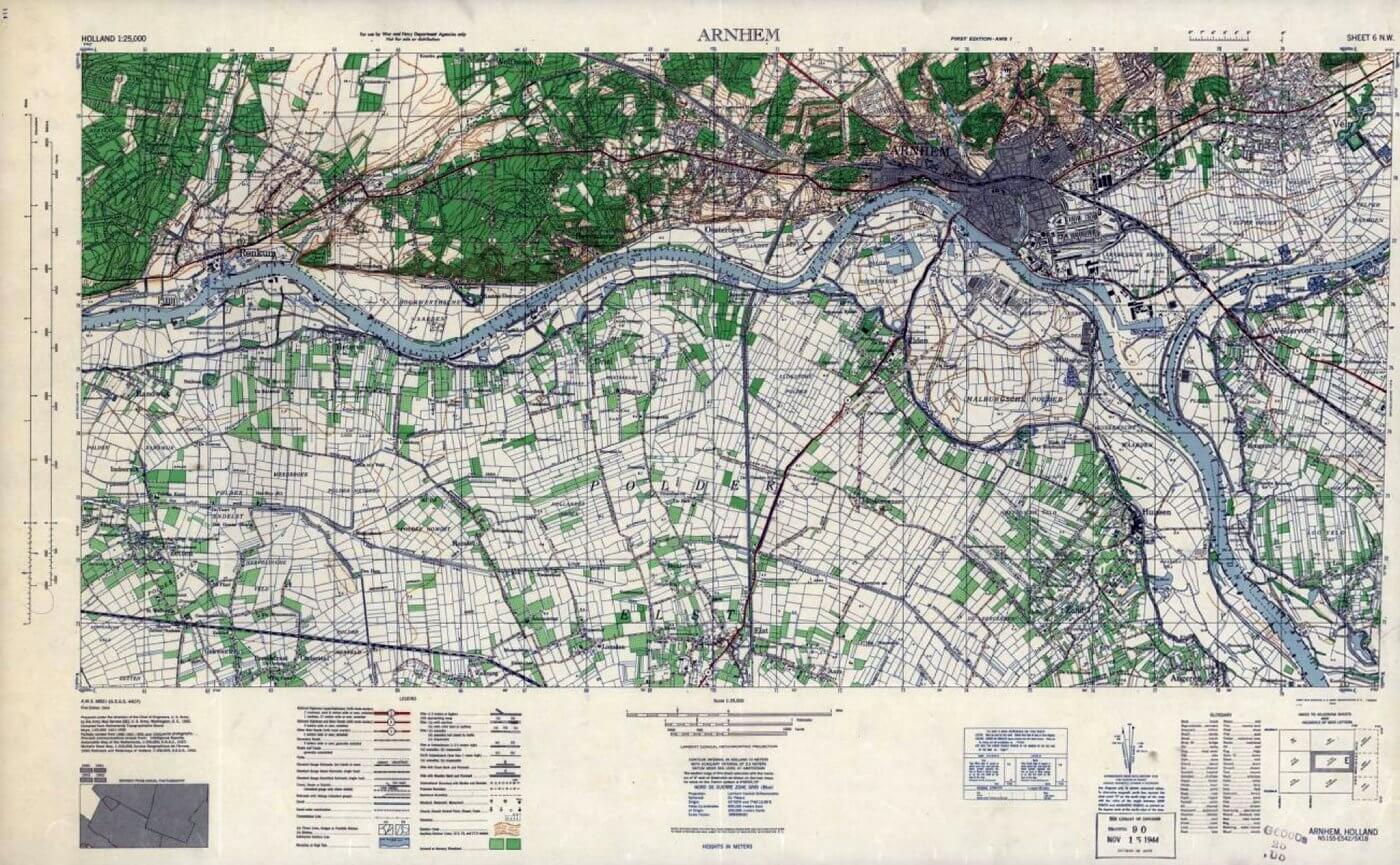

- Land at Landing- and Drop Zones at Wolfheze, Oosterbeek, and Ede.

- Capture the road bridge in Arnhem and hold it for a minimum of 48 hours

- Link up with the advancing ground forces of the 30th Corps.

| Operational Area |

Arnhem Area, The Netherlands

| Allied Forces |

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- 52nd, (Lowland) Airlanding Division

| Axis Forces |

- II SS-Panzer-Corps

- 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen”

- 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg”

- 6. Fallschirmjäger Regiment

- Bataillon I, Hauptmann Emil Priekschat

- Bataillon II, Hauptmann Rolf Mager

- Bataillon III, Hauptmann Horst Trebes

- Pionier Kompanie

- Panzerjäger Kompanie

- Fusilier Kompanie

- Kampfgruppe von Tettau

- Feldkommandantur 642

- SS-Unterführerschule Arnheim

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Polizei Schule

- SS-Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 4

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- SS-Wach Battalion 3

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 10

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 6/14

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 2

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 3

- Artillerie Regiment 184

- Sicherheit Regiment 42

- Kampfgruppe Knoche

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- MG Bataillon 30

- FlaK Abteilung 688

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Bataillon I

- Panzer Abteilung 224

- SS Ersatz Abteilung 4

- Deelen Airfield FlaK Kompanie

- Wach Kompanie

- Reichs AD

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Kampfgruppe Kraft

- SS-Panzer Grenadier Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 16

- Schwerepanzer Abteilung 506

- Schwerepanzer Kompanie Hummel

- StuG Abteilung 280

- Artillerie Regiment 191

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Werfer Abteilung 102, Hauptsturmfürer Nickmann

- Kampfgruppe Brinkmann

- Kampfgruppe Bruhn

- Kampfgruppe Harder

- Sperrverband Harzer

- MG Bataillon 47

- Marine Kampfgruppe 642

- Kampfgruppe Schörken

- Kampfgruppe Kauer

- SS-Abteilung “Landstrum Nederland”

- Kampfgruppe Knaust

- Ersatz Abteilung Bocholt

- Panzer Kompanie Mielke

- Kampfgruppe Spindler

- FlaK Abteilung Swoboda

- Kampfgruppe von Allworden

- Kampfgruppe Weber

| Withdrawal and Last Stand at Oosterbeek |

As said earlier two men who successfully reach the 1st Airborne Division positions bring copies of the withdrawal plan for Major-General Urquhart’s review. At 06:00, Urquhart receives a crucial message from Major-General Thomas of the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division. The message informs him that XXX Corps has abandoned any hope of reinforcing the 1st Airborne Division and advises that he should begin withdrawing his forces across the Rhine at a time of his choosing. With the perimeter at Oosterbeek showing clear signs of strain, Urquhart deliberates for two hours before contacting Thomas to confirm that the division will commence its withdrawal that night.

Despite the decision to withdraw, the battle at Oosterbeek is far from over. During the night, the Light Regiment intercepts German radio transmissions, revealing that a significant attack on the Lonsdale Force in the southeastern corner of the perimeter is imminent. This attack, directed against the Glider Pilots of G Squadron and the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, aims to breach the British lines and sever the division from the riverbank—a move that would effectively doom any withdrawal efforts.

Throughout the day, two battlegroups of experienced SS soldiers, Kampfgruppen Von Allworden and Harder, launch a series of coordinated attacks. The first assault penetrates the front-line defenses, targeting the Light Regiment’s positions near Oosterbeek Church. Despite their best efforts to engage the accompanying Tiger tanks, several of the regiment’s positions are overrun. The attack pushes deep into the perimeter before it is finally halted by a heavy bombardment from the 64th Medium Regiment, which fires directly into British lines to disrupt the German advance.

The 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment face similar pressure, with their line nearly collapsing under the weight of the assault. In one sector, a brutal close-quarters battle breaks out with German troops who have taken control of a wrecked building on the front line. The fight, described as a “snowball fight” with grenades, is resolved when one of the Light Regiment’s guns, firing at point-blank range, destroys the remaining structure, killing all but one of the attackers.

Despite further attacks on positions across the perimeter, the British lines hold firm. For the last time, Dakotas C-47’s of No. 575 Squadron, fly a limited number of sorties to Arnhem. Although only one aircraft is lost, the supplies once again fail to reach the 1st Airborne Division.

| Operation Berlin: The Withdrawal from Oosterbeek |

Major-General Urquhart’s plan for the withdrawal, codenamed Operation Berlin, is carefully designed to ensure that the Germans remain unaware of the impending evacuation. Urquhart knows that if the Germans suspect a withdrawal, they will launch a rapid and aggressive assault, potentially trapping the division on the northern bank of the Rhine. Major-General Urquhart, having studied the evacuation from Gallipoli in World War 1 during his time at the Staff College before the war, used similar techniques in planning this withdrawal. The plan involved a “collapsing bag” principle, where those positioned at the northernmost part of the perimeter would withdraw first. The operation relies on maintaining the illusion that the British forces intend to continue their defence at Oosterbeek.

Urquhart’s plan for withdrawal, built on this deception, is unlikely to withstand close German scrutiny or a determined offensive, so keeping the enemy at bay is vital. Both British and German artillery, positioned along the riverbanks, are central to the plan. At 20:50 hours, the Light Regiment, in coordination with the massed artillery of XXX Corps, will launch a fierce barrage. This intense fire plan is crucial, designed not only to suppress any German counterattacks but also to mask the sound of the British troops retreating from their positions. The barrage is set to continue throughout the night, shielding the withdrawing forces at their most vulnerable stage.

The intricate artillery plan is formulated by the gunners on the northern bank. Major Philip Tower and Lieutenant Paddy de Burgh, under difficult conditions, carefully draft the details. However, due to communication limitations, only part of the plan is transmitted via encoded “Slidex” to XXX Corps headquarters. The remaining details, too sensitive to send by radio, are personally delivered by Major Reggie Wight-Boycott Royal Artillery, who swims across the river to ensure its safe arrival. Ammunition is in short supply on both sides, but this night, no limits are placed on its use, without this artillery support, the withdrawal would be far riskier.

While most of the medical staff remain behind to care for the wounded, several radio operators stay with their sets, transmitting fictitious orders and false signals to distract the Germans. Some units, however, are too isolated to receive the evacuation order. One such unit is D Company of the 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment, located in the southwest of the perimeter, where they are effectively surrounded. Reduced to just nineteen men the day before, only five manage to escape the encirclement.

Those units in communication with Divisional Headquarters are instructed to fall back one by one under cover of the artillery. The phased withdrawal aims to keep the deception alive for as long as possible, with wounded personnel manning weapons and radios where needed. To avoid detection, all non-essential equipment is left behind, and strips of cloth are wrapped around boots to silence the sound of soldiers’ movements. The heavy rain, now an unexpected ally, helps to muffle their footsteps and limits German visibility.

Royal Engineers mark the paths down to the riverbank with white mine tape and place guides at critical junctions to ensure that troops do not stray in the darkness. Glider pilots, primarily from 1 Wing, Glider Pilot Regiment, are assigned this vital role. At 20:30 hours, the first troops begin abandoning their positions and heavy equipment to head for the river. The 2 Wing, Glider Pilot Regiment, with surviving Poles from the 3rd Polish Parachute Battalion under command, are included in the 1st Airlanding Brigade’s withdrawal, starting their extraction at 22:40 hours under the command of John Place.

While these plans are being circulated and preparations are underway, fierce fighting continues across Oosterbeek as the British forces hold off German attacks, allowing the withdrawal to proceed under the cover of night. Stealth is critical to the success of the operation. Troops blacken their faces, secure their weapons to minimize noise, and wrap their boots in rags to silence their movements. Any equipment that cannot be carried, such as radios, vehicles, and artillery, is destroyed to prevent it from being captured by the Germans.

During the day, the Schoonoord Hotel, now operating as the Main Dressing Station, is transformed into a Casualty Clearing Station. This change is not due to increased capability but rather the destruction of other medical stations. The hotel, though battered, continues to function as a hospital, with the operating theatre working at full capacity despite the battle raging outside.

Major-General Urquhart’s withdrawal plan for the troops on the north side of the river is sound. However, the 43rd Infantry Division’s headquarters mistakenly assumes that the previous night’s attempts to move men across the river have succeeded in expanding the perimeter. As a result, two evacuation points are chosen. One is located near the ferry site where troops have been landed the night before, and another near the artillery positions by the church in southern Oosterbeek. Unaware of this, Urquhart plans to direct all his men to the church area. Two routes to this location are marked out, each passing on either side of the Hartenstein Hotel.

Each crossing point is assigned two engineer companies: one from the 43rd Infantry Division equipped with assault crafts powered solely by the men rowing, and a Canadian engineer company with storm boats fitted with outboard motors. The Canadian boats can make the crossing in approximately three minutes, while the British boats, which must be paddled, take longer.

| Background and Initial Planning XXX Corps for Operation Berlin |

Around 10:00 hours, Major M.L. Tucker, commanding officer of the 23rd Canadian Field Company, attends an operational briefing led by the Chief Royal Engineer of the 43rd Infantry Division. The meeting focuses on the urgent task of evacuating the remaining troops of the 1st British Airborne Division from their besieged bridgehead across the Rhine. The situation is critical, with little information available regarding the number of troops needing evacuation or the precise locations for the operation. It is confirmed that stormboats will be the primary means of transport, and the 23rd Canadian Field Company is responsible for the off-loading and transportation of these boats to the launch sites using only their own resources.

Due to the lack of precise details, Major Tucker, alongside Lieutenant R.J. Kennedy, undertakes a reconnaissance mission to identify a suitable advanced marshalling area near Valburg, a likely operational zone. The terrain presents significant challenges; the area is low-lying, with roads elevated above the surrounding fields and bordered by wide, deep ditches. These narrow roads, with their soft shoulders, are unsuitable for heavy military traffic. However, a railway yard with a substantial area of hard standing is selected as the advanced company area, and a nearby tree-lined street is chosen to accommodate bridging vehicles.

| Preparation and Movement |

Upon returning to company headquarters in Nijmegen, Major Tucker finalises arrangements for the movement of personnel and bridging vehicles to the advanced positions. Lieutenants Kennedy and Tate are dispatched ahead to gather intelligence on the dispositions of both friendly and enemy troops in the area and to reconnoitre potential sites for the operation. Lieutenant Kennedy, who has prior reconnaissance experience from his time with the 204th Field Company, uses this knowledge to identify suitable locations for the evacuation.

Given the urgency, all available personnel and vehicles move forward to reach the advanced positions before nightfall. The convoy, consisting of three jeeps, two scout cars fitted with wireless equipment, two kitchen lorries, and twelve section 3-tonners, departs Nijmegen at 14:00 hours. Additional vehicles include one 3-tonner carrying twelve fitters and equipment repairers from the 10th Canadian Field Park Company, two formation padres, and seventeen bridging vehicles. The convoy navigates a perilous route, with narrow, winding roads through a corridor tenuously held by Allied forces. Despite the dangers, the convoy arrives intact at Valburg at 15:45 hours, with all vehicles dispersed and parked by 16:30 hours.

| Operational Planning and Execution |

At 17:15 hours, Major Tucker and his officers attend a briefing at the 130th Infantry Brigade Headquarters, where Lieutenant Kennedy reports that the two sites he identified earlier are deemed suitable for the evacuation operation. The Commander Royal Engineers of the 43rd Infantry Division confirms these sites for the night’s operations. The 260th Field Company is assigned to operate assault boats, while the 23rd Canadian Field Company is to use stormboats at a site northeast of Driel. The company is allotted fourteen stormboats and seventeen Evinrude motors, with a designated route forward to the operational site. Orders are given to commence launching stormboats at 21:40 hours, with a heavy artillery barrage scheduled to begin at 21:00 hours to mask the noise of off-loading and transporting the boats. A feint operation is also planned west of the main site to divert the enemy’s attention.

The operation begins under challenging conditions. Heavy rain softens the ground, turning the paths from the off-loading area to the launching sites into slippery, muddy tracks. Two floodwalls obstruct the path, one about 6 metres high with a steep 45-degree slope, and the other half as high with a gentler incline. These obstacles prove difficult to navigate, especially in the dark and with the heavy stormboats.

As the forward airborne troops prepare to move south, they are acutely aware that they need to ensure the Germans cannot follow closely behind them. With anticipation building, they anxiously check their watches, waiting for the crucial artillery support from their own guns and the heavier ones on the southern bank of the river. Brigadier Hubert Essame, commanding 217th Infantry Brigade, stands ready on the south bank, awaiting the start of the barrage. At 20:50 hours, the British artillery, along with XXX Corps’ massed guns, opens fire in a coordinated and deafening bombardment. Tracer fire from the Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment marks the flanks of the crossings, while Companies A and C of the 8th Battalion Middlesex Regiment add to the fire with mortars and medium machine guns.

The intensity of the firestorm lights up the night sky as the first boat is launched at 21:30 hours but is found to be severely damaged and rapidly taking on water, rendering it unfit for the crossing. The second boat, launched at 21:45 hours under the command of Lieutenant Martin, does not return and is believed to have been destroyed by a direct hit from a mortar. Subsequent boats are launched at 20-minute intervals, with all fourteen boats in the water by 03:30 hours. Several boats are holed by enemy fire or submerged obstacles but manage to reach the opposite shore before being abandoned. Despite the difficulties, the operation is carried out with a high degree of coordination under continuous enemy fire.

| Operation Berlin |

The withdrawal begins after dark, with the northernmost units, including the 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, silently leaving their positions and moving towards the embarkation points. They are followed in stages by other units, with the defense gradually collapsing in a controlled manner throughout the night. Some isolated units, such as D Company of the 1st Battalion, Border Battalion, remain unaware of the withdrawal due to their isolation. This company, reduced to just 19 men the previous day and surrounded in the southwest of the perimeter, manages to extract only five men.

Members of the Glider Pilot Regiment mark two routes to the river with tape and guide the withdrawing troops. The journey to the embarkation points is challenging, especially in the dark and worsened by rain, causing several groups to lose their way, and be captured. The operation was further aided by rain, and many soldiers muffled the sound of their boots by wrapping them with materials such as curtain fabric to reduce noise. Despite these difficulties, there is no panic at the embarkation points. Except for the walking wounded, who are given priority, all ranks of the division, from privates to generals, wait their turn to cross the river. The ferrying operation begins at 22:00, conducted by the 23rd Canadian Field Company’s powered boats and the paddled assault boats of the 260th (Wessex) Field Company.

Due to a misunderstanding, XXX Corps believes that the 4th Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment has secured enough of the Westerbouwing high ground to allow some of the division’s men to withdraw through that area. As a result, nearly half of the available boats spend the night at this crossing point, but they manage to evacuate only 48 men, mostly Dorsets who had been hiding since the previous evening. By the time it becomes clear that the division will not use this area for evacuation, it is too late for these boats to assist with the main operation.

The operation faces significant challenges, including intense enemy fire from machine guns, mortars, and 88 millimetres guns. While the rain provides some cover, it also causes mechanical issues with the Evinrude motors, leading to frequent breakdowns. Despite the efforts of Engineering and Maintenance personnel and fitters, many motors fail during the operation, adding to the difficulties.

Enemy fire is particularly heavy on the river and on both shores. Machine guns, set on fixed lines, sweep the river and beaches, but much of the fire is high, missing the boats. However, as daylight breaks, the machine guns on the hills above the bridgehead intensify their fire, making it increasingly dangerous for the boats still operating. Mortar and artillery fire fall across the entire area, resulting in many casualties among the airborne troops at the bridgehead. On the river and south bank, casualties are lighter but still significant. Three men are wounded in the off-loading area, and another is injured en route to the beach. Enemy snipers are also active, but some airborne troops are able to neutralise sniper positions during their crossing.

| Multimedia |