| September 17th, 1944 – September 26th, 1944 |

| Operation Market Garden |

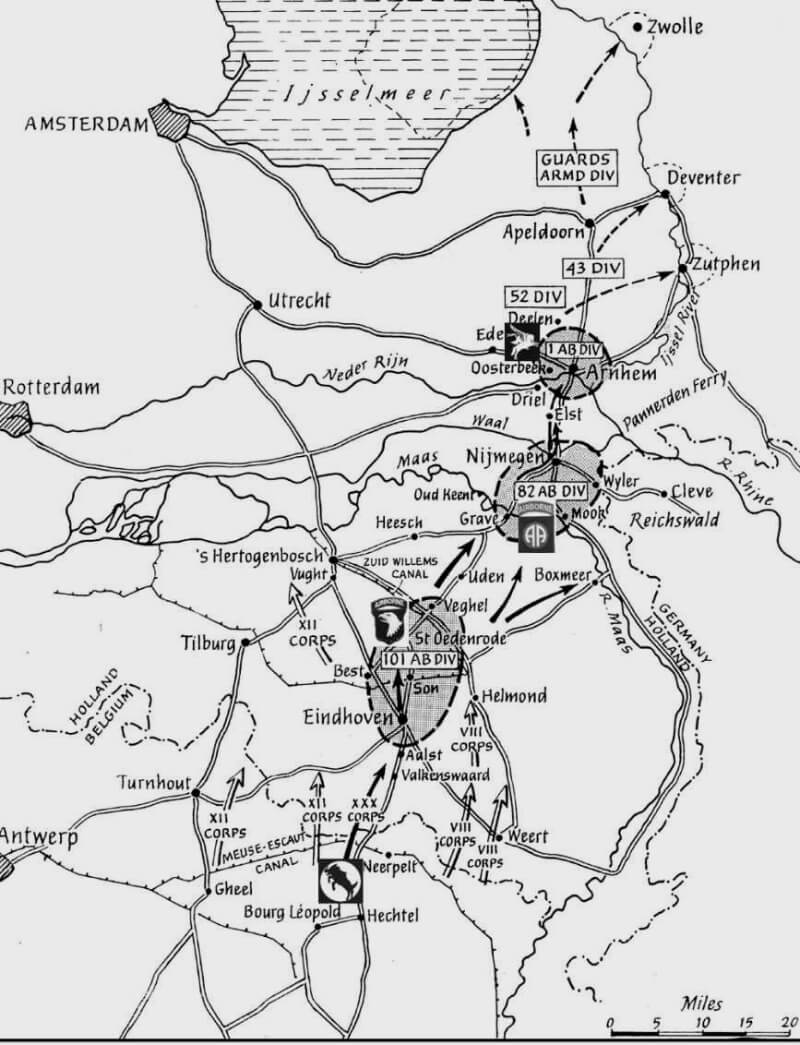

| Objectives |

- Land south of the Arnhem road bridge

- Support the 1st Airborne Division in holding the bridge for a minimum of 48 hours.

- Link up with the advancing ground forces of the 30th Corps.

| Operational Area |

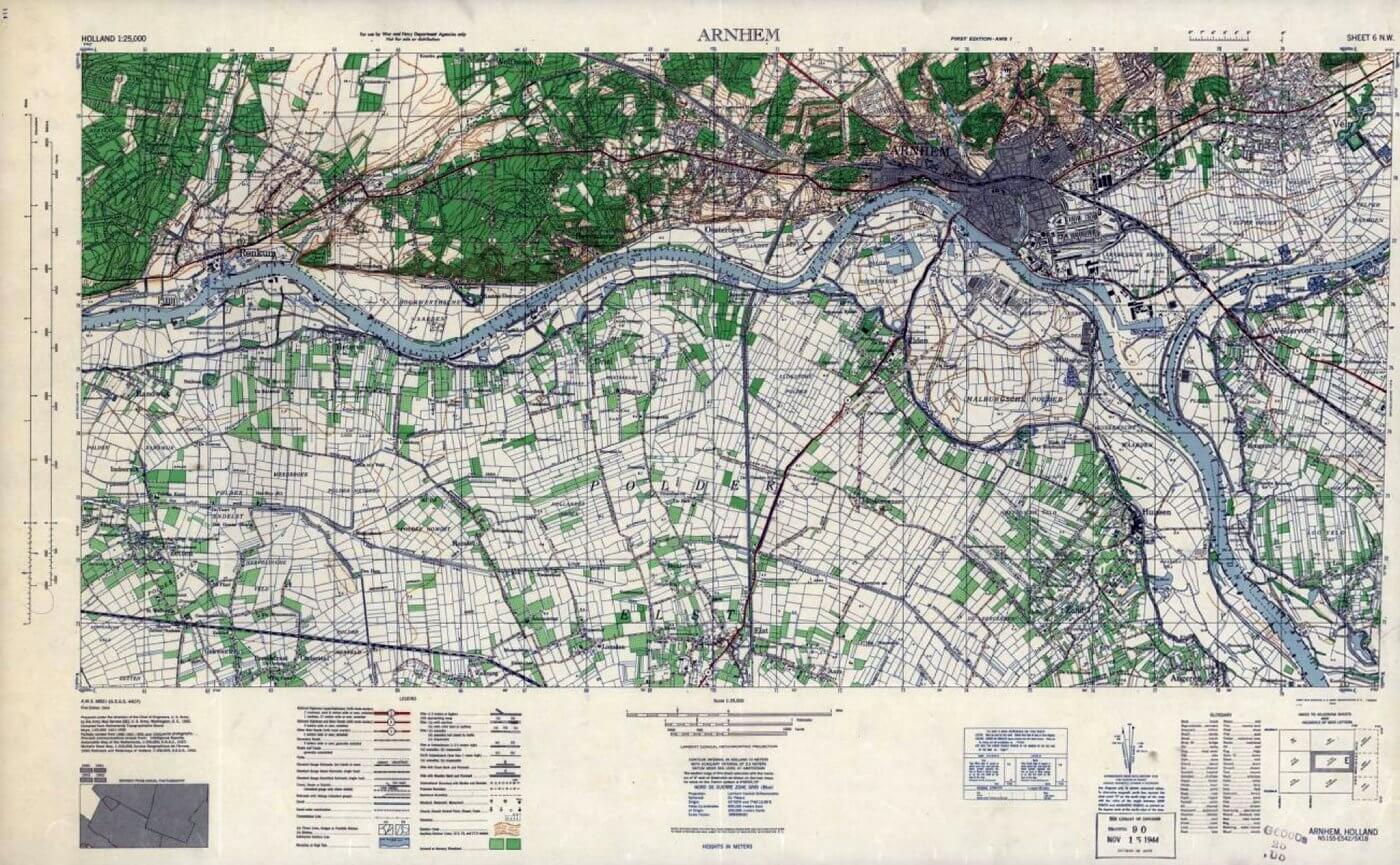

Arnhem Area, The Netherlands

| Allied Forces |

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- 52nd, (Lowland) Airlanding Division

| Axis Forces |

- II SS-Panzer-Corps

- 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen”

- 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg”

- Kampfgruppe von Tettau

- Feldkommandantur 642

- SS-Unterführerschule Arnheim

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Polizei Schule

- SS-Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 4

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- SS-Wach Battalion 3

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 10

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 6/14

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 2

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 3

- Artillerie Regiment 184

- Sicherheit Regiment 42

- Kampfgruppe Knoche

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- MG Bataillon 30

- FlaK Abteilung 688

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Bataillon I

- Panzer Abteilung 224

- SS Ersatz Abteilung 4

- Deelen Airfield FlaK Kompanie

- Wach Kompanie

- Reichs AD

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Kampfgruppe Kraft

- SS-Panzer Grenadier Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 16

- Schwerepanzer Abteilung 506

- Schwerepanzer Kompanie Hummel

- StuG Abteilung 280

- Artillerie Regiment 191

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Werfer Abteilung 102, Hauptsturmfürer Nickmann

- Kampfgruppe Brinkmann

- Kampfgruppe Bruhn

- Kampfgruppe Harder

- Sperrverband Harzer

- MG Bataillon 47

- Marine Kampfgruppe 642

- Kampfgruppe Schörken

- Kampfgruppe Kauer

- SS-Abteilung “Landstrum Nederland”

- Kampfgruppe Knaust

- Ersatz Abteilung Bocholt

- Panzer Kompanie Mielke

- Kampfgruppe Spindler

- FlaK Abteilung Swoboda

- Kampfgruppe von Allworden

- Kampfgruppe Weber

| Operation |

The 1st Airborne Division is supported by the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, under the command of Major General Stanisław Sosabowski, which is scheduled to be dropped south of the road bridge after the initial landings.

On September 12th, 1944, at Moor Park Golf Club in Hertfordshire, the morning begins with an Air Force conference, focused on the allocation of aircraft and gliders for the upcoming operation. The Brigade Group is assigned 114 aircraft and 45 Horsa gliders. Due to the limited number of gliders available, the Brigade’s light artillery will not be brought into action. The anti-tank battery can only take their guns, jeeps, and two men per gun, while transport and heavy equipment for other units must be reduced to a bare minimum, especially when compared to the provisions of similar British units.

From the outset, Major-General Sosabowski expresses concerns about the plan, as he did with the earlier Operation Comet. He considers the execution of Comet equivalent to a “suicide mission.” Whether his criticism influenced the decision to delay Comet remains unclear. During the briefing for Operation Market on 12th September, Sosabowski once again raises concerns. He argues that the distance between the landing zones and the objective, coupled with the spread of operations over three days, diminishes the element of surprise, which is crucial for the success of lightly armed airborne forces.

Sosabowski is also sceptical of the assumption made by British commanders that the Germans will offer minimal resistance. British intelligence officer Brian Urquhart (not to be confused with Roy Urquhart, commander of the 1st British Airborne Division) provides evidence of significant German troop concentrations near Arnhem. Shortly after, Brian Urquhart is transferred, and later events prove his concerns accurate, as strong SS Panzer divisions are located near Arnhem, regrouping after fighting in France.

Sosabowski fears that by the time his paratroopers land on the third day, the Germans will have consolidated their forces at the strategically critical bridge. His lightly armed troops would then be faced with heavily armed German units, while his anti-tank guns would either be stationed north of the Rhine or still in transit by road.

Sosabowski’s criticism is not born out of unwillingness to participate but from a desire to protect his troops and the British forces from unnecessary risk if the plan is not feasible. Despite his reservations, Sosabowski remains committed to his role and follows British orders faithfully, as long as they are documented in writing.

What surprises Sosabowski most, beyond the operation itself, is the relaxed attitude of the British high command. His dedication to the operation and deep concern for his men sharply contrasts with the more distant approach of the British generals. These officers, many of them from elite backgrounds, struggle to appreciate the perspective of a Polish officer with limited English and a middle-class background. Despite these challenges, Sosabowski understands that this mission represents a crucial opportunity for his brigade to contribute to the liberation of Western Europe, and indirectly, Poland.

Later that day, at 17:00 hours, the Commander of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade, Major-General Sosabowski meets with the Commander of the 1st Airborne Division Major-General Urquhart for a briefing on Operation Market. The task is delivered orally, with written orders expected by the 16th of September. A summary of the order is provided as an enclosure.

Throughout the night of September 13th, 1944 and into the following morning at Royal Air Force Stamford, the operational plan for the Brigade Group is worked out in detail.

The 1st Independent Polish Parachute Brigade is divided into three sections for its deployment:

- Seaborne Tail: On August 16th, 1944, the brigade’s heavier equipment is shipped to France for overland transport. At the time, it is not yet known that Arnhem will be the target for this “seaborne tail.” Due to a shortage of transport aircraft, the shipment includes eight 75-millimetre howitzers, 113 vehicles, including the Brigade’s ambulances, and three anti-tank guns.

- Anti-Tank Unit: Armed with 15 six-pounder anti-tank guns, this unit is flown to landing zones north of the Rhine by gliders on the second and third days of the operation. The 10 gliders on the second day will land on Landing Zone S, Seven Horsa gliders transport No. 3 Troop of the Anti-Tank Battery, including five 6-pounder anti-tank guns, as well as the accompanying troops, jeeps, trailers, and supplies. Two additional Horsas carry the heavy equipment for the Engineer Company, while the final Horsa delivers the advance party for the Brigade Headquarters. The 20 Polish gliders on the third day on Landing Zone L. They carry the Commanding Officer of the anti-tank battery and two additional troops of the Polish Anti-Tank Battery, with a total strength of 50 men and 10 guns. The Landing Zones are the same landing zones where British troops are deployed. Due to limited space in the gliders, only two Polish soldiers accompany each gun, while the rest of the gun crews arrive later via parachute drops. Until then, British glider pilots serve as temporary gun operators. According to the original plan, the anti-tank unit is expected to secure the northeastern flank once the Airborne Division captures Arnhem.

- Main Brigade: The remainder of the Polish brigade is scheduled to drop near Elden on Drop Zone K, south of the river, on the third day of the operation. The 1,500 paratroopers wil be brought in by 114 Dakotas. Their objective is to secure the traffic bridge and, if necessary, capture it before moving north to join the British troops and secure the eastern flank.

At 17:00 hours, commanders of battalions and special units of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade are informed of the Major-General Sosabowski’s plan, and the battalion commanders begin formulating their own specific approaches.

On September 14th, 1944, in Royal Air Force Stamford, during the morning, Major-General Sosabowski reviews the battalions’ plans, adding further details and ensuring all aspects are coordinated. By 16:00 hours, the Commander of the 1st Airborne Division and the Division Artillery Officer meet with the Major-General Sosabowski and his Chief of Staff to discuss how the task will be carried out, specifically the crossing of the Brigade to the northern bank of the River Rhine. The evening is spent by Brigade Group Headquarters and the battalions working through further planning and finalizing details.

On September 15th, 1944, in Royal Air Force Stamford, the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Chief of Staff heads to the Headquarters of the 1st and 4th Parachute Brigades to coordinate efforts regarding securing the river crossing. Discussions take place on taking over the defensive sector from the two parachute brigades. At 12:30 hours, a coordination conference is held between the Brigade Group Commander, the battalion commanders, engineers, and the anti-tank officers.

During the morning of September 16th, 1944, in Royal Air Force Stamford, a conference is held involving the battalion commanders and company commanders to further align plans and strategies.

| Passwords |

Like the 1st Airborne Division, the passwords for the initial days at Arnhem were similar for the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade, as specified in the operational orders, are as follows:

- H Hour to September 17th, 1944: Challenge, “Red,” Reply, “Beret.”

- September 18th, 1944, D+1: Challenge, “Uncle,” Reply, “Sam.”

- September 19th, 1944, D+2: Challenge, “Carrier,” Reply, “Pigeon.”

- September 20th, 1944, D+3: Challenge, “Air,” Reply, “Borne.”

- September 21st, 1944, D+4: Challenge, “Robert,” Reply, “Burns.”

- September 22nd, 1944, D+5: Challenge, “Troop,” Reply, “Carrier.”

Only five days’ worth of passwords were originally planned, and once these were exhausted, New passwords had to be created. There are indications that Challenge “Mae”, Reply, “West” was used on September 24th, 1944. Passwords for Saturday and Monday might be missing. Most likely passwords were arranged locally by Headquarters.

| September 17th, 1944 |

Once Operation Market Garden has started Major-General Sosabowski is shocked to find that wireless communication between his headquarters in Great Britain and General Urquhart’s 1st Airborne Division in Arnhem is almost non-existent. The lack of reliable updates leaves Sosabowski anxious and reliant on scarce, often redundant, information from official channels. His concerns are shared by Lieutenant-Colonel George Stevens, his British Chief Liaison Officer.

Meanwhile, General Browning, responsible for leading ground troops, also struggles with communication, as his headquarters lacks a long-range transmitter. This further complicates efforts to coordinate with higher command, leaving Sosabowski in a frustrating state of uncertainty.

As Operation Market nears, Polish commanders meet for final briefings. At the airfields, soldiers and ground crews prepare for departure, with the names of three Polish women written on a glider, symbolizing hope for success. On the first day, Lieutenant Alphons Wojciech Pronobis parachutes into Drop Zone X as part of the initial effort.

| September 18th, 1944 |

Major-General Sosabowski and his team learn through newspapers that the Allied Airborne Army has landed in the Netherlands and that the 1st Airborne Division is heavily engaged in fighting near Arnhem. Although some units have reached the bridge, they control only one end, with the Germans holding the other. The situation remains uncertain, with the battle far from being won. Lieutenant-Colonel George Stevens provides more updates, but it becomes clear that the element of surprise is lost, and further airborne operations will face well-prepared German defenses, increasing the risk and lowering effectiveness.

At 11:00 hours, ten Airspeed Horsa gliders take off from Royal Air Force Manston, carrying essential personnel and equipment for the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. Among the passengers are Polish officers, including war correspondent Marek Swiecicki. As they take off in gloomy weather, the atmosphere is tense but focused. Once airborne, the clouds give way to sunlight, revealing a vast formation of planes headed for the Dutch coast.

The gliders encounter light anti-aircraft fire but land successfully at 15:00 hours near Oosterbeek. The landings are rough but effective, with the troops quickly moving to secure their positions. Despite some close encounters with enemy fire, all ten gliders successfully deliver their cargo without casualties. The Polish Anti-Tank Battery sets up a defensive perimeter around Hotel Hartenstein after receiving orders not to advance toward Arnhem, as the city remains inaccessible.

Back at Royal Air Force Spanhoe and Royal Air Force Saltby, ground crews work tirelessly to prepare para-containers filled with ammunition, medical supplies, and food for the upcoming airborne assault. That evening, Major-General Sosabowski sends a report to Polish Headquarters, informing them of his brigade’s imminent departure.

| September 19th, 1944 |

As the Third Lift of the Polish Airlanding forces approaches Landing Zone L, held by the 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, the tension rises. This area is critical for the arrival of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Group, including 50 men and 10 anti-tank guns. However, thick fog in England delays most Polish parachutists, grounding them for the day. Eventually, the weather clears enough for the glider contingent to proceed, though this delay causes great anxiety among the waiting 1st Airborne Division.

At Landing Zone L, the British face light German resistance and some shelling, with enemy aircraft appearing briefly but causing minimal damage. Still, the expected Polish reinforcements are delayed, heightening the 1st Airborne Division’s concerns. Meanwhile, the 4th Parachute Brigade faces mounting pressure from advancing enemy forces, while some battalions retreat towards Landing Zone L, closely pursued by the Germans. The Polish and British forces must act quickly as they find themselves increasingly outnumbered and surrounded.

When the Third Lift eventually takes off from 12:00 onward, it includes stragglers from previous lifts and 15 gliders carrying personnel and equipment for the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. Despite anti-aircraft fire and other dangers, 34 of the 35 Polish gliders reach their landing zone, though some are damaged by enemy fire. The Germans quickly respond to the landings, targeting the gliders and landing troops, leading to intense combat. Only three of the ten Polish anti-tank guns are successfully unloaded, with two reaching Oosterbeek to reinforce defensive positions. Unfortunately, other gliders are destroyed by enemy fire, and some land in German-held areas, with their crews captured.

Despite the heavy toll, including nine Polish casualties, the troops regroup and begin to move towards their assigned positions. Major-General Sosabowski’s personal jeep is captured by the Germans, leading to false reports of his death.

Meanwhile, Major-General Sosabowski prepares the rest of his brigade for departure from England. On the day of their scheduled takeoff, thick fog delays the mission. Sosabowski and his troops remain on standby, with the airfield bustling with activity as jeeps and containers are loaded onto aircraft. The fog persists throughout the day, eventually forcing the mission to be postponed.

Sosabowski is informed that a second glider lift, which took off earlier, faced difficult weather conditions but may have encountered enemy resistance during landing. This unconfirmed report unsettles him, though later updates suggest the situation was less severe than feared. The Polish troops return to their billets, preparing for a rescheduled take-off the following day.

| September 20th, 1944 |

As the situation deteriorates near Arnhem, Major-General Urquhart revises the plan for the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade, redirecting them to the village of Driel, about 1.6 kilometres south of the Oosterbeek perimeter. The Poles are to use the Driel-Heveadorp ferry to cross the Rhine and reinforce the embattled British troops. This ferry, not originally part of the Market Garden plans, gains strategic importance as the Arnhem bridge is lost and the perimeter tightens.

By Wednesday, the ferry is disabled when the ferryman sinks it to prevent German use. Despite this setback, communication from the 1st Airborne Division informs the Polish Brigade of their new landing zone, now six kilometers west of the original one near Driel, within range of British artillery.

That morning, the 1st Polish Brigade arrives at the Royal Air Force airfields, only to be met with new orders. General Sosabowski quickly reorganizes his split forces between two airfields, instructing a delay in takeoff to 13:00 to adapt to the new plan. Despite efforts, worsening weather forces the operation to be postponed once again, giving Sosabowski’s troops an additional 24 hours to refine their plans. By evening, they return to their garrison areas, and Lieutenant-Colonel Stevens delivers troubling news: the 1st Parachute Brigade is in dire straits near Arnhem, with one battalion cut off at the bridge and the rest of the 1st Airborne Division under intense pressure.

Stevens also reports that XXX Corps is stalled, casting doubt on the overall success of the operation. Concerned about the growing risks, Sosabowski decides to seek direct assurances from higher command, fearing that outdated intelligence may lead his troops into an untenable situation. This bold decision, while risking accusations of insubordination, reflects Sosabowski’s priority to safeguard his men from unnecessary harm.

In Oosterbeek, where the Polish anti-tank battery is positioned, the situation remains critical. Under heavy artillery fire, Polish units fight to support the British on the northwestern side of the perimeter. After receiving orders to destroy a German self-propelled gun, one Polish crew is killed, and their gun is destroyed in action. As the Germans intensify their attacks from both the west and east, Polish anti-tank units move to reinforce the southern perimeter. Despite suffering casualties, they establish defensive positions near Oude Kerk and Kneppelhoutweg, prepared to resist further German assaults aimed at isolating the British from XXX Corps.

| September 21st, 1944 |

At 07:00, Major-General Sosabowski is informed that the ferry at Heveadorp is under British control, and the plan for the brigade’s deployment remains unchanged. With this assurance, Sosabowski prepares his men for departure, confirming the operation in a coded message to Polish Headquarters.

At Saltby Airfield, preparations begin amidst lingering mist. Despite previous delays, the spirits of the 1,568 men of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade remain high. By noon, the aircraft engines roar to life, and between 14:00 and 14:30, 114 Dakotas from the 314th and 315th Troop Carrier Groups take off. However, bad weather forces 41 aircraft to turn back, with miscommunication on the recall code further complicating the situation. Of the remaining 73 aircraft, 72 successfully reach the drop zone in the Netherlands, though they are met with heavy anti-aircraft fire, resulting in the loss of five C-47s and ten American aircrew members.

Despite these obstacles, 957 paratroopers land near Driel by 17:18. Under fire, they quickly regroup. Sosabowski learns that the ferry has been scuttled, preventing any immediate crossing of the Rhine to reinforce British troops. The brigade establishes defensive positions around Driel, prepared to confront German forces.

Upon landing, Sosabowski’s troops face sporadic shelling and mortar fire as they advance toward the ferry. A reconnaissance patrol confirms that the ferry is unusable and the northern bank of the Rhine is under German control. Unable to cross the river, Sosabowski sets up his headquarters in the village of Driel, where his forces dig in for the night, awaiting further orders and the possibility of crossing.

Meanwhile, the medical company establishes an emergency hospital in a local school, treating 159 wounded, including Polish, British, and Dutch civilians. By 22:30, Captain Zwolanski swims across the Rhine to deliver a situation report from the 1st Airborne Division, informing Sosabowski that they are ordered to cross the Rhine and join the defensive perimeter. However, the lack of boats or rafts makes this task impossible.

Attempts to re-establish communication with the Polish Brigade prove difficult due to equipment failures. As the night progresses, the British engineers work to construct makeshift rafts using Jeep trailers, while the Poles explore ways to build rafts on their side of the river. Both efforts face delays and complications. By dawn, neither side has successfully constructed enough rafts to facilitate a crossing. The brigade is forced to maintain defensive positions around Driel, unable to reinforce the British forces at Oosterbeek.

Meanwhile, the Polish anti-tank units stationed near Oosterbeek continue to endure heavy mortar and artillery fire, suffering further casualties but holding their positions. The battle for Arnhem and the surrounding areas intensifies, with the Polish forces remaining crucial to the overall defensive effort.

| September 22nd, 1944 |

At 01:00 hours, a Royal Engineers officer from the 1st Airborne Division informs Major-General Sosabowski that a raft is nearly completed for a potential river crossing. By 03:00, however, Sosabowski realizes that attempting a crossing in the dark would be too risky, and a daylight crossing would result in heavy casualties. He decides to relocate most of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade to Driel, where they will regroup and establish defensive positions.

By 05:30, the Brigade arrives in Driel and quickly sets up defensive positions in a hedgehog formation. The 2nd Parachute Battalion is tasked with fortifying the perimeter, while Brigade Headquarters, Engineer Company, and Anti-Tank Battery are strategically placed. Local civilians assist the soldiers with tools for digging trenches. However, as daylight breaks, the Germans, holding higher ground across the river, begin shelling the Polish positions, leading to casualties, including the death of Lieutenant Slesicki.

By 08:45, a reconnaissance platoon from the Household Cavalry arrives in Driel, enabling Sosabowski to establish communication with General Horrocks at XXX Corps Headquarters. Throughout the day, repeated German attacks target the Polish defensive positions, supported by tanks and artillery. Patrols are sent out to gather intelligence, and one returns with a German prisoner and information about heavily defended areas near Arnhem. Another solo mission by Lieutenant Detko successfully reaches General Thomas at the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division, relaying vital information.

In the late afternoon, British forces from XXX Corps, including Sherman tanks from the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards, arrive in Driel, linking up with the Polish Brigade. Their arrival helps reinforce the Polish defensive line and halt a German attack. Sosabowski’s quick leadership, even cycling to the frontlines on a borrowed bicycle, bolsters morale and ensures the coordination of British and Polish forces.

Despite establishing a connection with XXX Corps, the position in Driel remains precarious, with the brigade exposed and vulnerable to counterattacks. German forces divert significant troops to block any potential Polish or British advances, but the Poles maintain control of Driel despite intense German assaults throughout the day.

Captain Zwolanski successfully re-crosses the Rhine, reporting the Polish situation to the 1st Airborne Division at dawn. Lieutenant Colonels Mackenzie and Myers cross the river and arrive at Driel, using the Household Cavalry’s radios to contact General Horrocks. Plans to ferry the Polish troops across the river to reinforce the British perimeter are underway, but logistical challenges arise. Attempts to deploy amphibious DUKW’s are thwarted as the vehicles become bogged down in mud near the river.

With the failure of the DUKW’s, the Polish and British forces resort to using small rubber dinghies. Throughout the night, only 40 to 50 Polish soldiers are ferried across the Rhine under heavy fire. Captain Faulkner-Brown of the Royal Engineers plays a critical role in coordinating this crossing, but despite their best efforts, the number of troops successfully crossing is too small to make a significant impact.

By 04:00, the operation is halted due to exhaustion and increasing German interference. While this partial link-up provides some reinforcements, the broader strategic situation remains dire. The 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade holds Driel, but they are unable to reinforce the British forces on the northern bank in large numbers, complicating the overall operation’s objectives.

| September 23rd, 1944 |

At 03:00, the Officer Commanding the Parachute Engineer Company reports to Major-General Sosabowski that the attempt to ferry more troops across the Rhine is proving impossible. With only 52 troops successfully ferried, and heavy losses—15% of the soldiers on the southern bank killed—the operation is becoming untenable. Both rubber boats and rafts have been lost, further complicating the mission.

Throughout the night and into the day, Driel is heavily shelled by German forces, further devastating the town and impacting the makeshift hospital’s ability to care for the wounded. The weather is grey and damp, with fog providing limited visibility, but this does not deter the increasing enemy shelling and mortar fire.

At 09:00, Sosabowski receives a liaison officer from Airborne Corps, who informs him that another attempt to cross the river is expected that night, with the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division attempting to break through to the southern bank during the day. Sosabowski agrees to the plan but emphasizes the need for more boats and supplies, as only one boat remains from the previous night’s failed crossing.

Meanwhile, the remaining troops of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade that had been delayed in Great Britain are redirected to a drop zone near Grave, 25 kilometers from Driel. By 16:45, these troops land successfully but are too far from Driel to offer immediate assistance.

Polish troops have established defensive positions in Driel, laying anti-tank mines and preparing for further German attacks. Throughout the day, the Germans launch assaults on the Polish positions, forcing them to retreat. Despite the heavy pressure, the Polish troops manage to hold their lines, with assistance from local villagers. However, the situation remains critical, with the Poles facing continuous shelling and limited supplies.

The first group of Polish soldiers that crossed the Rhine on the previous night moves to reinforce the British positions at Oosterbeek. They help defend against enemy tanks and neutralize German machine gun nests, but their numbers are too few to make a significant impact.

After the failure of the previous night’s crossing attempts, Sosabowski’s Chief of Staff, Major Malaszkiewicz, travels to the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division to secure proper assault boats. By 19:00, plans are in place to ferry the 3rd Parachute Battalion first, followed by other units. However, logistical challenges continue, with food and ammunition supplies failing to reach the 1st Airborne Division due to DUKW vehicles becoming stuck on the southern bank.

At 23:00, the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade prepares to move to the crossing area, but the boats fail to arrive in time, leaving the brigade in a precarious position as they await further opportunities to cross the river and support the embattled British forces in Oosterbeek. Despite the setbacks, the Polish engineers remain determined to press forward with the operation.

| September 24th, 1944 |

At around midnight, the Polish forces faced increased German artillery and machine-gun fire. Delays in the arrival of boats from XXX Corps and the absence of Canadian crews forced Polish engineers to man the boats themselves. With limited capacity and under intense fire, the first crossing was delayed until 03:00. The chaotic situation at the riverbank, along with the limited capacity of the boats, added to the confusion.

As the troops approached the river, they encountered fixed German lines of fire. Despite determined efforts, many boats were either lost or rendered unusable, leading Sosabowski to order a shift to a different crossing point. However, heavy fire and the difficult conditions continued to impede progress. By dawn, only 153 soldiers had successfully crossed, far fewer than expected, and many of them were quickly evacuated due to severe injuries.

Following the failed crossing, Sosabowski returned to Driel, saddened by the heavy casualties. At 10:00 hours, Lieutenant-General Horrocks of XXX Corps arrived to assess the situation. Sosabowski briefed him on the precarious state of the airborne troops north of the Rhine and recommended either a large-scale reinforcement or a withdrawal. Horrocks chose the reinforcement option, but plans were also made for a possible evacuation.

At 11:30 hours, Sosabowski attended a conference at the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division headquarters. The meeting, led by Major-General Thomas and attended by other British commanders, discussed plans for a night crossing involving the Dorsetshire Regiment and the 1st Parachute Battalion. Sosabowski voiced his concerns about the plan, arguing that it would result in heavy casualties, but his input was largely ignored.

Later that evening, 551 soldiers from the 1st Parachute Battalion and parts of the 3rd Battalion finally arrived in Driel after weather delays. Sosabowski ordered them to join the planned night crossing, alongside the Dorsetshire Regiment.

Meanwhile, Polish troops who had crossed during the previous night were deployed to the western side of the Oosterbeek perimeter, relieving British forces. They faced continuous German attacks, including tank assaults, but managed to hold their ground. Communication between the Polish and British troops was sometimes facilitated in German, due to language barriers.

At 21:00, the 2nd Parachute Battalion was ready to cross the Rhine, but the operation was delayed due to a shortage of boats. Eventually, the boats were handed over to the Dorsetshire Regiment, which began crossing at 01:00 on September 25. The crossing was met with heavy German fire, and despite initial success, over 200 of the 315 men who crossed were captured. The crossing was halted, and further attempts were abandoned.

| September 25th, 1944 |

By 05:00, orders are given to the newly arrived Polish units, including the 1st Parachute Battalion and the remainder of the 3rd Parachute Battalion, to establish defensive positions. Major-General Sosabowski’s brigade, divided between the north and south banks of the Rhine, continues its efforts despite little progress being made over the past days. The route from Oosterhoud to Valburg remains open, used by ambulances and vehicles, but Sosabowski is frustrated by XXX Corps’ failure to cover the relatively short distance to reach the Neder Rhine.

On the north bank, under General Urquhart’s command, the Polish glider troops, elements of the 3rd Parachute Battalion, anti-tank, and signal companies are entrenched. On the south bank, under Sosabowski, are the 1st and 2nd Battalions, engineers, medical units, and support elements. By midday, Sosabowski receives a message that the evacuation of the northern bank units is expected that night, and his brigade is tasked with assisting the survivors upon their arrival on the southern bank.

The 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade prepares to relocate south to Valburg, where they will regroup and support the next phase of operations. Heavy artillery and mortar fire throughout the day result in significant casualties, with over 40 wounded soldiers treated, six of whom die from their injuries. Even the field hospital is hit by shellfire, killing two ambulance drivers.

In Oosterbeek, the relentless German attacks continue. Polish troops defending positions along the Stationsweg are subjected to constant mortar fire, artillery, machine-gun fire, and sniper attacks. Their headquarters suffers a direct hit, and the makeshift hospital is evacuated, indicating an imminent German assault. Although the Polish troops manage to destroy a German tank and a motorized gun, their last anti-tank guns are disabled. The pressure mounts as the Germans close in on the beleaguered troops.

By 06:00, Major-General Urquhart receives a decisive message from Major-General Thomas of the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division: XXX Corps has abandoned hope of reinforcing the 1st Airborne Division, and Urquhart is advised to begin withdrawing his forces. With Oosterbeek’s perimeter showing signs of collapse, Urquhart confirms that the division will withdraw that night, launching Operation Berlin, the evacuation plan.

Urquhart’s plan relies on stealth and deception to keep the Germans unaware of the withdrawal. Troops on the northern edge of the perimeter will withdraw first, giving the appearance that the defense continues. The 43rd Division artillery provides cover by bombarding German positions, and non-walking wounded are left behind with some medical staff to maintain the illusion of strength. Radio operators stay to transmit false orders, further deceiving the enemy.

The withdrawal plan involves two engineer companies: one British with manual assault boats and one Canadian with motorized storm boats. The faster Canadian boats handle most of the evacuation, with the British boats taking longer. Troops blacken their faces, wrap their boots in rags, and destroy non-essential equipment to ensure a quiet withdrawal. However, a misunderstanding in the 43rd Division leads to two evacuation points being established instead of one, complicating the operation.

Polish troops on the Stationsweg are ordered to withdraw at 22:00, but before they can retreat, they fend off a fierce German attack, managing to kill a high-ranking German officer. The fighting is intense, but the Polish forces hold their ground until they can begin their withdrawal under the cover of night, as part of the larger evacuation effort of Operation Berlin.

| September 26th, 1944 |

Operation Berlin was the Allied withdrawal across the Rhine River from Oosterbeek following the failure of Operation Market Garden. During this operation, the 1st Airborne Division, supported by the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade led by Major-General Sosabowski, was tasked with retreating from the heavily besieged area. Sosabowski’s Polish troops provided a rear guard to cover the retreat. The conditions were extremely challenging, with heavy rain, mud, artillery barrages, and a shortage of boats. Canadian engineer units made approximately 150 trips across the Rhine during the night, transporting around 2,500 men in total, despite damaged records from the rain.

The Polish troops, covering the withdrawal, experienced difficulties due to a lack of boats, forcing many soldiers to cross the river by any means available. Some swam across, while others were left behind, captured by German patrols, or killed during the final stages of the withdrawal. It was estimated that around 100 Polish soldiers remained on the north side of the Rhine, including wounded who could not be evacuated. Despite the chaos and loss, many soldiers managed to cross the river, though the toll was heavy, with 50 Polish soldiers killed in Oosterbeek or drowned during the evacuation.

After the evacuation, the Polish Brigade withdrew to Nijmegen, where Major-General Sosabowski met with General Urquhart and later reported to Browning’s Headquarters. The Polish brigade had lost approximately 400 men, with significant officer and enlisted casualties. Despite these losses, Browning assigned them to guard an airfield near Grave, where they faced continued threats from German forces. Tensions emerged when the brigade was placed under the command of the 157th Infantry Brigade, leading to friction as Sosabowski, a Major-General, was expected to take orders from a lower-ranking Brigadier. This move was interpreted by Sosabowski as undermining his authority, especially given his strong-willed nature and his leadership during the recent operations.

The brigade was later involved in defending critical infrastructure and conducting night patrols along the River Maas, which sometimes led to capturing enemy soldiers. During this time, they also assisted the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division by providing successful patrols to capture German prisoners. The brigade eventually returned to England, where they regrouped after being relieved from their duties in early October 1944.

Sosabowski faced significant challenges upon his return to England. The failure of Operation Market Garden led some senior Allied commanders to seek a scapegoat, and criticism of the Polish brigade began to circulate. Field Marshal Montgomery wrote to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, harshly criticizing the Polish brigade’s performance during the battle and suggesting their removal from the theater. Similarly, General Browning wrote a detailed critique of Sosabowski’s command. In December 1944, Sosabowski received a letter from the Polish President-in-Exile, informing him of his removal from command. The letter gave no reason for his dismissal but acknowledged his bravery and dedication during the battle.

Many believed that Browning, who was preparing to take a new position in Southeast Asia, was behind Sosabowski’s removal. Sosabowski’s departure caused a protest within the brigade, with two Polish units going on a hunger strike during Christmas in a show of solidarity with their former commander, though it did not change the outcome. Despite Sosabowski’s leadership and the sacrifices of the Polish brigade, they were unfairly blamed for the failure of Operation Market Garden. The brigade, though deeply affected by the experience, remained intact but faced an uncertain future as they regrouped and recovered in England.

| Multimedia |