| September 17th, 1944 – September 26th, 1944 |

| Operation Market Garden |

| Objectives |

- Land at Landing- and Drop Zones at Wolfheze, Oosterbeek, and Ede.

- Capture the road bridge in Arnhem and hold it for a minimum of 48 hours

- Link up with the advancing ground forces of the 30th Corps.

| Operational Area |

Arnhem Area, The Netherlands

| Allied Forces |

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- 52nd, (Lowland) Airlanding Division

| Axis Forces |

- II SS-Panzer-Corps

- 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen”

- 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg”

- Kampfgruppe von Tettau

- Feldkommandantur 642

- SS-Unterführerschule Arnheim

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Polizei Schule

- SS-Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 4

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- SS-Wach Battalion 3

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 10

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 6/14

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 2

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 3

- Artillerie Regiment 184

- Sicherheit Regiment 42

- Kampfgruppe Knoche

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- MG Bataillon 30

- FlaK Abteilung 688

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Bataillon I

- Panzer Abteilung 224

- SS Ersatz Abteilung 4

- Deelen Airfield FlaK Kompanie

- Wach Kompanie

- Reichs AD

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Kampfgruppe Kraft

- SS-Panzer Grenadier Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 16

- Schwerepanzer Abteilung 506

- Schwerepanzer Kompanie Hummel

- StuG Abteilung 280

- Artillerie Regiment 191

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Werfer Abteilung 102, Hauptsturmfürer Nickmann

- Kampfgruppe Brinkmann

- Kampfgruppe Bruhn

- Kampfgruppe Harder

- Sperrverband Harzer

- MG Bataillon 47

- Marine Kampfgruppe 642

- Kampfgruppe Schörken

- Kampfgruppe Kauer

- SS-Abteilung “Landstrum Nederland”

- Kampfgruppe Knaust

- Ersatz Abteilung Bocholt

- Panzer Kompanie Mielke

- Kampfgruppe Spindler

- FlaK Abteilung Swoboda

- Kampfgruppe von Allworden

- Kampfgruppe Weber

| Reorganising the perimeter |

At 07:30 hours, after the surrender of the remaining troops Lieutenant Colonel Frost in Arnhem, Major-General Roy Urquhart holds a critical meeting with his surviving staff and senior commanders at the Hartenstein Hotel. His main focus is now on maintaining a defensive perimeter around Oosterbeek to secure a bridgehead for the approaching XXX Corps. He divides the responsibility between his two brigade commanders.

Brigadier “Pip” Hicks is given command of the western perimeter. His section extends from the junction of Stationsweg and Graaf van Rechterenweg, down Valkenburglaan, and along Van Borsselenweg to Heveadorp, which includes the Driel ferry crossing. Despite significant losses, his troops are positioned as follows: the Reconnaissance Squadron, 7th Battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers, 21st Independent Parachute Company, 4th Para Squadron, Royal Engineers, 2 Wing of the Glider Pilot Regiment, and 1st Battalion, Border Regiment.

On the eastern side of the perimeter, Brigadier “Shan” Hackett takes charge. His forces, also heavily depleted, are arranged from right to left: 11th Parachute Battalion around the west, south, and east of Oosterbeek Church. The 2nd Battalion, South Staffords, is positioned from south of the Hofwegen laundry to the riverbank at the junction of Benedendorpsweg and Polderweg. The remnants of 1st Parachute Brigade cover the area from Rozensteeg and Weverstraat to the flank of 10th Parachute Battalion, which occupies four houses near the Schoonoord Hotel along Utrechtseweg.

Further north, glider pilots from “D” Squadron hold a thin defensive line from the crossroads, linking up with 156th Parachute Battalion around Stationsweg and Joubertweg. The lines of both brigade sectors meet here, with the Reconnaissance Squadron and 7th Battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers positioned on the left flank of the paratroopers.

Most of the Glider Pilots are deployed throughout most sections of the Oosterbeek perimeter. The main reserve consists of 20 Flight from B Squadron, and 10 and 24 Flights from G Squadron. Major Dale and C Squadron serve as the only reserve for 1st Airlanding Brigade. Meanwhile, the vulnerable southeast section is defended by 1 Flight from ASquadron, 3 and 4 Flights from B Squadron, and 9 and 23 Flights from G Squadron. The Glider Pilot group fighting in the north-western woods consists of the remnants of E and F Squadrons. Many of these pilots never reunite with their own units but instead spend the entirety of the battle in Oosterbeek integrated into other units.

It’s important to note that all of these units have been severely reduced in strength by now. Many junior officers are either wounded or killed, and the remaining soldiers are battalions and companies in name only. Nevertheless, they remain determined to fight on until the arrival of XXX Corps.

| Assault on the Perimeter |

At 08:00, the Germans launch a coordinated assault on the positions within the perimeter held by the 1st Airborne Division. The most significant blow comes at the Westerbouwing Restaurant, located on the high ground in the southwestern corner of the perimeter and defended by B Company of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment. Taken by surprise, the company is attacked by several German tanks and an infantry battalion from the Hermann Göring Schule Regiment. Although the forward platoon manages to inflict heavy casualties on the advancing infantry, they are forced to retreat when their only Bren gun jams. The two platoons on the flanks resist fiercely but are eventually overwhelmed, with most of the men captured. The survivors abandon the restaurant but manage to stall the advancing tanks with a determined rearguard action. Despite three attempts by the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment to recapture this crucial high ground, they are unsuccessful.

Losing Westerbouwing is a severe setback. The Driel-Heveadorp ferry crossing, which the Polish forces intend to use later in the day, falls into German hands. Additionally, the base of the perimeter along the Rhine shrinks to just 640 metres, less than half its original length, placing the entire division in jeopardy. If pushed further from the riverbank, the division faces the risk of being overrun. However, Major Charles Breese quickly reorganises the surviving troops, forming a unit known as Breeseforce. This group, consisting of an under-strength platoon, two depleted platoons from A Company, No. 17 Platoon of C Company from the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, and a small number of paratroopers, establishes a strong defensive position that the Germans are reluctant to challenge for the remainder of the battle.

| Press Conference in Hotel Hartenstein |

During the morning, in the former reception hall of Hotel Hartenstein, a small table is set up with a map spread across it. General Urquhart, the Divisional Commander, prepares to brief the war correspondents who have gathered. He begins by outlining the situation.

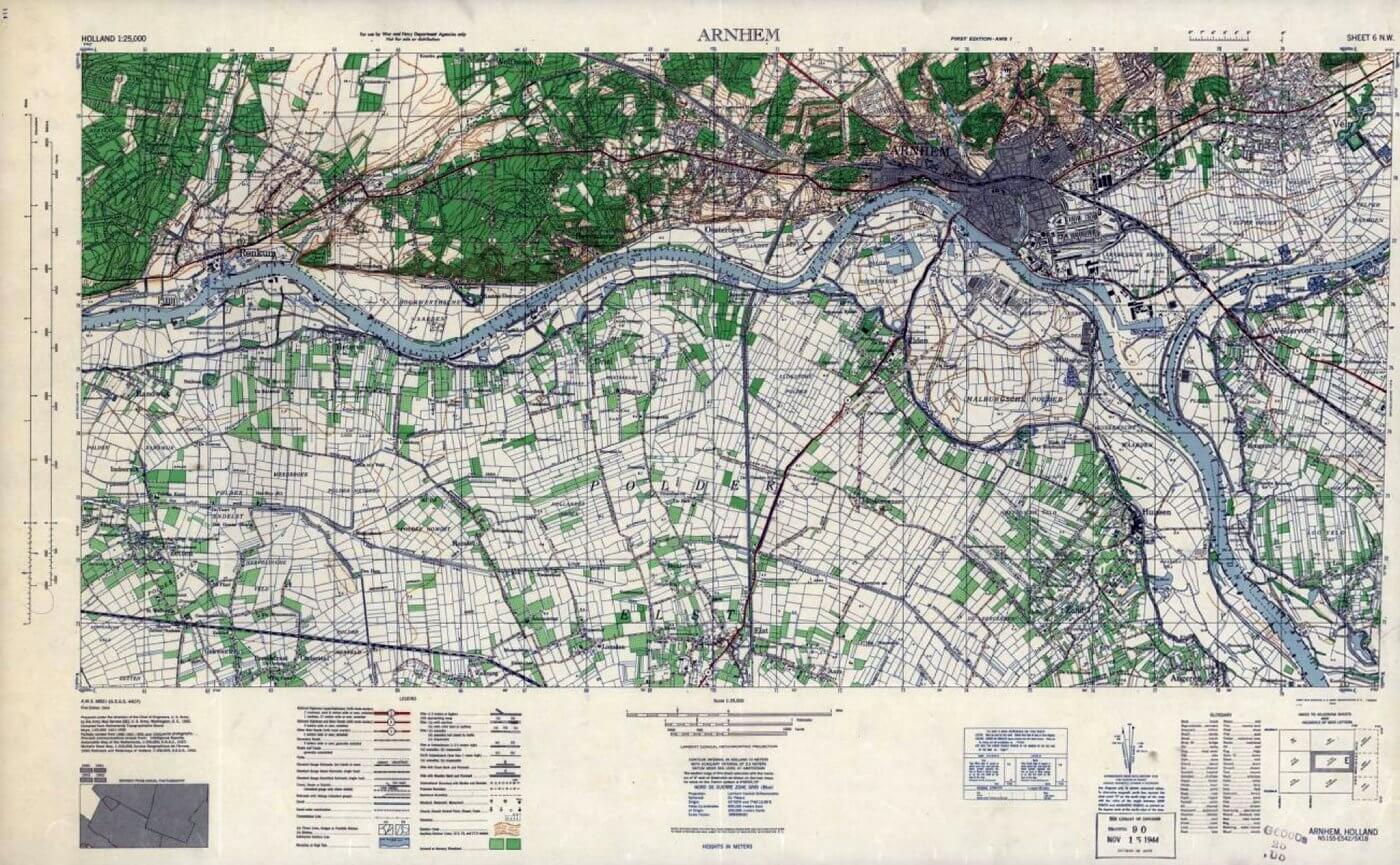

The General discusses the initial position on the first day, which had appeared favourable but carried potential complications. The Division is isolated on the northern bank of the Lek, the lower Rhine. Capturing Arnhem had been difficult from the outset, and it is now out of reach. The Germans are continuously reinforcing their positions, leaving the Division to wait for the Second Army, which is fighting its way through Nijmegen, to make contact.

Pointing to the map, the General explains, “At this moment, the Division is practically surrounded. However, the current opposition consists of relatively small enemy forces. While they limit maneuverability and keep the Division stationary, larger German forces are advancing from the west, north of Arnhem.” He indicates two large blue rings on the map. “These forces are still several kilometers away, moving through areas held by their own troops. They may reach this area today, certainly by tomorrow, which will complicate the situation.”

He also addresses the supply challenges, noting, “The supply situation is not ideal, though the air force is doing everything possible. Looking ahead, the situation will either resolve in our favour by Sunday, or…”

With a slight smile, he adds, “At present, there are a few troops in reserve for defense, along with the war correspondents.” The General briefly comments on the instructive military nature of the situation displayed on the map.

When asked about the arrival of the Polish Brigade, the General responds, “The Poles were expected on Tuesday, then Wednesday, and now we hope they will arrive today. Bad weather has been preventing them from leaving England. Their arrival would be most welcome.”

The briefing ends with the General extending his well wishes, as he bids them farewell.

| Intense Fighting for the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment |

Throughout the day, the other companies of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment face heavy engagements. The morning begins with intense mortar fire targeting A, C, and D Companies. In the northwest, A Company repels three infantry assaults during the day and another at night. By the time the last attack comes, their ammunition is nearly depleted, so they hold their fire until the enemy is just 30 metres away, inflicting heavy casualties and breaking up the assault.

In the center of the battalion’s position, C Company faces similar attacks from the front. Their situation becomes precarious when an enemy platoon attempts to outflank them with machine-gun support. Acting on his own initiative, Corporal Swan leads a counterattack with bayonets and grenades, killing many of the attackers and forcing the rest to retreat.

Near Westerbouwing, D Company endures heavy mortar bombardment and is further harassed when two tanks approach and rake their trenches with machine-gun fire. The company’s anti-tank guns struggle to find a clear line of sight. However, when a corporal in one of the crews is killed, his comrades, angered, fire six shots in quick succession when the tank breaks cover, destroying it. They must be physically restrained from continuing to fire. The exposed nature of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment’s position, particularly around C and D Companies, leaves them vulnerable to enemy observation, making it difficult to relocate, bury the dead, or evacuate the wounded.

| Struggles in the Eastern Perimeter |

The eastern perimeter, near the Rhine, also faces significant challenges. In the morning, German infantry launch a fierce assault on the Lonsdale Force, but they are quickly and decisively repelled by small-arms fire and artillery from the Light Regiment. In response, the Germans heavily shell the area, causing casualties among the artillerymen, including the wounding of their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Thompson. In the afternoon, German tanks resume the attack but are again repelled. Major Cain, now leading the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, plays a key role in this defence, displaying remarkable bravery under fire, earning him the Victoria Cross, the only one awarded to a survivor of the Arnhem battle.

Further north, the 10th Parachute Battalion comes under similar attacks from along the Utrechtseweg. Initially, they hold their ground, but a self-propelled gun is brought in, making it difficult for the paratroopers to counter its fire as it repeatedly strikes the occupied buildings, causing heavy casualties. German infantry exploit these gaps and gradually push the 10th Parachute Battalion out of their positions, leading to intense hand-to-hand combat. During this phase, most of the battalion is overrun, and all of its officers, including their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Smyth, are lost. Despite this, isolated pockets of resistance, led by Captain Barron of the 2nd Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, manage to hold out until Brigadier Hackett sends in the 21st Independent Parachute Company to relieve them the following day. The remnants of the 10th Parachute Battalion are then withdrawn into reserve. Despite the intensity of the fighting, the Germans gain little ground.

| The Battle at Hotel Dreyeroord |

The final major engagement of Thursday occurs at the northernmost positions around the Dreyeroord Hote, known to the 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers as the White House. Throughout the day, the Germans continuously harass the 300 men defending this area. However, in the morning, two platoons from the Borderers launch a surprise attack on three enemy machine-gun positions and a group of infantry. The assault is successful but costly, with one platoon attacking from the front and the other from the rear after maneuvering around the enemy.

The pressure on the position continues, culminating in a determined German infantry assault at 16:30. The attack penetrates deep into the defences of the 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers but is repelled by two bayonet charges, one led by Lieutenant-Colonel Payton-Reid and the other by Lieutenant Taylor and his No. 12 Platoon. The Borderers reclaim all lost ground, leaving an estimated 100 German dead around the hotel. However, the cost is high, with half of the Borderers becoming casualties. As a result, the position is deemed indefensible, and after evacuating the wounded, the battalion withdraws to a more secure position further south. Major-General Urquhart then orders the other exposed units in the north, including the 21st Independent Parachute Company and part of the 4th Parachute Squadron, to withdraw into reserve.

That very same day, something more powerful than mortars grenades begins to land within Oosterbeek area. It soon becomes clear that it is regular artillery fire. There was concern that the enemy had shifted their targeting from Hartenstein to Oosterbeek.

Polish Captain Mackowiak, Artillery Liaison Officer to 1st Airborne Division, Artillery, identifies the artillery as friendly fire and immediately rushes to the battery command to radio for the allied forces to cease fire. A few minutes later, the artillery barrage stops, leaving only the mortars to continue their assault on Oosterbeek. It turns out that these shells are fired from Nijmegen, approximately 21 kilometres from Arnhem, by the 64th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery. Radio contact with a Type 22 radio set is first established around 09:45, with the initial fire support missions coordinated by 10:30. The 64th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery, equipped with two batteries of 114 millimetres guns and one battery of 140 millimetres guns, is positioned about 6.5 kilometres south of Nijmegen, approximately 20 kilometres from Oosterbeek.

The No. 1 Forward Observation Unit, tasked with coordinating artillery support from XXX Corps, is now able to direct fire in support of the airborne troops. Initially, the first rounds fired fell short of their targets due to the extreme range of the 5.5-inch guns. However, the 64th Medium Regiment quickly adjusted by moving its guns closer to Nijmegen, allowing them to accurately strike German positions identified by the airborne artillery observers. From this point onward, the entire perimeter could be supported with medium artillery fire, providing a significant morale boost for Urquhart’s forces. The increasing effectiveness of the artillery support signaled that XXX Corps was drawing closer to their positions.

The 75 millimetres pack howitzers of the Divisional artillery fire shells weighing 7.5 kilograms, whereas the shells from Nijmegen weigh 45 kilograms. In the following days, many of the targets are located within 150 metres of the perimeter positions. On two occasions, fire is directed within the perimeter to disrupt German forces that have managed to infiltrate.

| Arrival of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade |

The 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade is planned to leave for Arnhem at 12:00. As midday approaches, worsening weather leads to another delay in takeoff. However, by 14:00, the order is given to proceed, and at Saltby and Spanhoe, the engines of 114 Dakotas from the 314th and 315th Troop Carrier Groups roar to life.

The American pilots face significant challenges, struggling to climb through thick cloud cover and form their designated formations. During the chaotic ascent, one paratrooper mistakenly jumps over Cambridgeshire but rejoins on a later mission. As the weather deteriorates further, a decision is made to recall the aircraft to avoid unsafe conditions. However, a miscommunication over the recall code, where the codes given to radio operators differed from those used by ground stations, complicates matters. The recall code is sent four times, but its interpretation varies among pilots. As a result, 41 Dakotas turn back, with most landing at the nearest airfield after descending through the clouds. Notably, one aircraft even lands in Ireland.

Of the 41 returning aircraft, 25 carry men from the 1st Parachute Battalion, 2 carry personnel from the 2nd Parachute Battalion, 11 from the 3rd Parachute Battalion, and 3 carry members of Brigade Headquarters.

Meanwhile, the remaining 73 aircraft press on over Belgium. During the flight, one Dakota carrying Brigade Headquarters personnel is hit by flak after straying into German-held territory. The plane turns back to Belgium, drops its troops, and then returns to England. The remaining 72 aircraft, carrying 1,003 men, continue the mission. At around 17:00, the Polish paratroopers finally make their combat jump. They are met with heavy anti-aircraft fire, resulting in the loss of five Dakota C-47’s. Although all paratroopers manage to jump before the planes crash, ten American aircrew members lose their lives. The evasive maneuvers taken by the aircraft to avoid enemy fire cause delays in the paratroopers’ jump, and as they descend, they come under fire from German troops on the ground, leading to five fatalities and 25 wounded. Despite these challenges, the drop is considered successful, and the Brigade faces no significant resistance in the immediate area.

Five aircraft from the 315th Troop Carrier Group are lost to enemy fire, but all paratroopers aboard safely jump before the planes crash. Unfortunately, 10 American aircrew members are killed, with others wounded or captured.

The 500 Polish paratroopers aboard the aircraft that returned experience a further 48-hour delay before they are finally dropped near Grave, within the 82nd Airborne Division’s area, on Saturday, 23rd September. By this time, the original drop zones closer to the Rhine are deemed too dangerous to use.

After landing, having only two battalions to his diposal, the Polish paratroopers regroup under Major General Sosabowski’s command. The 3rd Parachute Battalion sets up defensive positions along the riverbank near Oosterbeek, while the 2nd Parachute Battalion moves towards the Driel-Heveadorp ferry to attempt a crossing of the Rhine and reinforce the Allied forces.

Upon reaching Driel, Sosabowski is informed by locals that the ferry is no longer operational, which comes as a shock since the ferry was critical to their plan. Unknown to the Polish forces, the ferry had been deliberately scuttled by its operator to prevent German use after they captured Westerbouwing. Additionally, the Polish troops are unaware that German forces now control the opposite bank.

Sosabowski sends a team led by Lieutenant Kaczmarek and Captain Budziszewski to investigate. They reach the ferry site under cover of darkness, but when they attempt to signal any Allied presence across the river, they are met with heavy German gunfire. The team takes cover and, after the gunfire subsides, withdraws to Driel. They report back that no further action can be taken that night, leaving the Polish forces unable to cross the river and join the main Allied force.

The arrival of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade across the river briefly raises spirits within the perimeter, but this momentary boost is quickly dampened by another round of German artillery fire and renewed assaults.

The men within the perimeter are nearing the limits of their endurance, physically and mentally exhausted, yet acutely aware that they must hold on to survive. The question constantly on their minds is, “Where is XXX Corps?”

Major General Urquhart grows increasingly concerned about the prolonged delay in the arrival of XXX Corps. He fears that its commander, Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, does not fully understand the severity of his division’s situation. Recognising that relief must come that very night, Urquhart decides to send his chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Mackenzie, and his chief engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Myers, across the river to convey the urgency directly to Horrocks and Lieutenant General Browning, the corps commander.

| Resupply Mission |

The resupply of the airborne forces in Oosterbeek is becoming increasingly challenging for Allied aircrews, with 117 Stirlings and Dakotas taking part in the resupply mission for that day. The Allies struggle to maintain air superiority, and Operation Market Garden can no longer dominate the allocation of fighter escorts. On this particular day, many of the U.S. fighters that typically accompany supply drops are diverted to escort a major bombing raid over Germany. Additionally, poor weather ove Great Britain prevents some Royal Air Force squadrons from joining the mission.

Seizing this opportunity, the Luftwaffe, rarely in a position to outnumber Allied formations, makes an aggressive push. Messerschmitt Bf 109’s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190’s break through the reduced fighter escort, targeting the vulnerable, slow-moving supply planes. In conjunction with effective anti-aircraft fire, the German defenses cause significant losses. Twenty-nine Royal Air Force aircraft are shot down, representing a staggering 25% of the British formation. 190 Squadron Royal Air Force suffers particularly, losing seven of the ten Stirlings it sent on the mission. Despite the heavy sacrifices, much of the valuable supply drop falls into German hands rather than reaching the British forces on the ground.

| A Day of Heavy Losses |

The day proves exceptionally difficult across the entire perimeter, with around 150 British troops killed defending their positions since first light. Despite these heavy losses, there is a glimmer of hope as the Polish forces arrive on the southern bank, and the artillery from XXX Corps begins to provide much-needed support. The mood remains defiant, with no talk of defeat, as each man steels himself for the next day’s battle.

At 22:00 hours, the divisional perimeter is adjusted by withdrawing further south. The 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers is repositioned to the edge of the woods near Hartenweg and Bothaweg. They maintain contact on their left with the glider pilots of E and F Squadrons, while the 1st Reconnaissance Squadron holds their right flank, with 9th Field Company, Royal Engineers, in reserve just behind them.

| Multimedia |

In the distance, several burnt-out buildings stand just beyond the British-controlled zone. Among them is the heavily damaged Walburgiskerk, which caught fire when a German Messerschmitt crashed into one of its towers.

In the photograph, the extent of the heavy fighting on and around the Rhine Bridge during the Battle of Arnhem is clearly visible. Taken on September 21, the image captures both the physical destruction and the human toll of the fierce clashes between British and German forces, highlighting the devastation wrought in the area.

The photo mentioned above was taken on the ramp leading to the Rhine Bridge, clearly showing the damage from the fierce battles of the preceding days.