| September 17th, 1944 – September 26th, 1944 |

| Operation Market Garden |

| Objectives |

- Land at Landing- and Drop Zones at Wolfheze, Oosterbeek, and Ede.

- Capture the road bridge in Arnhem and hold it for a minimum of 48 hours

- Link up with the advancing ground forces of the 30th Corps.

| Operational Area |

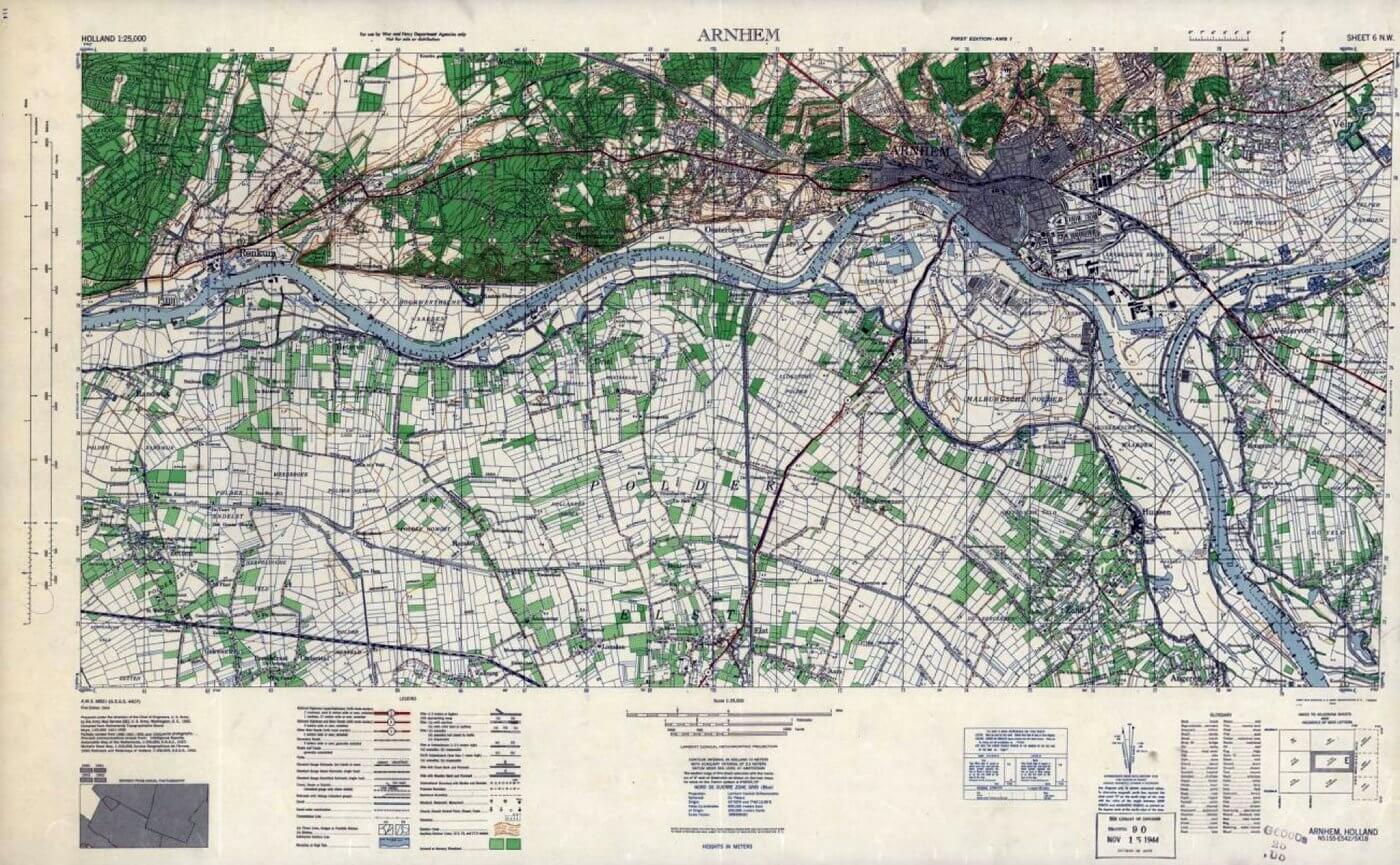

Arnhem Area, The Netherlands

| Allied Forces |

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- 52nd, (Lowland) Airlanding Division

| Axis Forces |

- II SS-Panzer-Corps

- 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen”

- 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg”

- 6. Fallschirmjäger Regiment

- Bataillon I, Hauptmann Emil Priekschat

- Bataillon II, Hauptmann Rolf Mager

- Bataillon III, Hauptmann Horst Trebes

- Pionier Kompanie

- Panzerjäger Kompanie

- Fusilier Kompanie

- Kampfgruppe von Tettau

- Feldkommandantur 642

- SS-Unterführerschule Arnheim

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Polizei Schule

- SS-Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 4

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- SS-Wach Battalion 3

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 10

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 6/14

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 2

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 3

- Artillerie Regiment 184

- Sicherheit Regiment 42

- Kampfgruppe Knoche

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- MG Bataillon 30

- FlaK Abteilung 688

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Bataillon I

- Panzer Abteilung 224

- SS Ersatz Abteilung 4

- Deelen Airfield FlaK Kompanie

- Wach Kompanie

- Reichs AD

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Kampfgruppe Kraft

- SS-Panzer Grenadier Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 16

- Schwerepanzer Abteilung 506

- Schwerepanzer Kompanie Hummel

- StuG Abteilung 280

- Artillerie Regiment 191

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Werfer Abteilung 102, Hauptsturmfürer Nickmann

- Kampfgruppe Brinkmann

- Kampfgruppe Bruhn

- Kampfgruppe Harder

- Sperrverband Harzer

- MG Bataillon 47

- Marine Kampfgruppe 642

- Kampfgruppe Schörken

- Kampfgruppe Kauer

- SS-Abteilung “Landstrum Nederland”

- Kampfgruppe Knaust

- Ersatz Abteilung Bocholt

- Panzer Kompanie Mielke

- Kampfgruppe Spindler

- FlaK Abteilung Swoboda

- Kampfgruppe von Allworden

- Kampfgruppe Weber

| Glider Landing of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade |

As the Third Lift with the Polish Airlanding forces approaches the 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers holds a critical defensive position around Landing Zone L. This location is of paramount importance as it is where the gliders carrying the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Group are expected to land. The Polish gliders carry the Commanding Officer and two additional troops of the Polish Anti-Tank Battery, with a total strength of 50 men and 10 guns. The remaining gun crews are due to arrive later via a parachute drop with the main body of parachutists, set to drop on Drop Zone K, approximately 1.6 kilometres south of Arnhem Bridge. In the meantime, British Glider Pilots temporarily take their places. However, a thick fog blankets the airfields in England, grounding the majority of the Polish parachutists and canceling their lift. Although the Royal Air Force glider airfields are similarly affected by fog, it eventually lifts, allowing the glider segment of the Third Lift to proceed.

The 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, face relatively light enemy interference at Landing Zone L, despite a heavy shelling around midday. Earlier in the day, a small number of German fighter aircraft strafes the British positions. Although their attack causes minimal damage, the mere presence of enemy aircraft, after having enjoyed near-total Allied air superiority, catches the British off guard.

As the scheduled time for the Third Lift passes with no sign of the gliders, the 1st Airborne Division becomes increasingly anxious. They are unaware of the delays caused by the weather and anxiously await the much-needed reinforcements. This delay places the 4th Parachute Brigade of the 1st Airborne Division in a precarious situation. Meanwhile the 10th Parachute Battalion and the 156th Parachute Battalion of the 1st Airborne Division are retreating from their positions towards Landing Zone L, pursued closely by enemy forces, including armoured vehicles. The possibility that the zone could be overrun before the gliders land looms large.

The situation is further complicated by the 4th Parachute Brigade’s need to cross south of the railway line to regroup with the rest of the 1st Airborne Division and attempt another advance toward Arnhem. Unbeknownst to them, the 11th Parachute Battalion of the 1st Airborne Division has failed to secure the critical high ground at Heijenoord-Diependal. The Brigade identifies two potential crossing points for their vehicles: the stations at Oosterbeek and Wolfheze. It is assumed that both, if not already in German hands, soon will be. The closer Oosterbeek Hoog station lies at a junction with Dreijenseweg, which is firmly under German control. Initially, the Brigade plans to attack this area, but intelligence from the Dutch Resistance reveals that a large enemy force, Kampfgruppe von Tettau, is closing in from the west. Alarmed by this news, the Brigade decides to take a longer route to secure Wolfheze before the enemy arrives. With the 7th Parachute Battalion of the 1st Airborne Division unable to abandon Landing Zone L and the two parachute battalions being squeezed against the railway line by advancing enemy forces from three directions, the 4th Parachute Brigade finds itself in dire straits.

This lift, that starts taking off from 12:00 on, is the third glider operation for the 1st Airborne Division, included not only stragglers from previous lifts but also 15 Horsas departing from Royal Air Force Keevil. These gliders carried personnel and equipment from the Brigade’s Headquarters, Signals, Medical, and Transport and Supply Companies, with a total cargo of twenty-two jeeps, eleven trailers, and thirty-five men. The gliders were towed by aircraft from No. 196 Squadron and No. 299 Squadron, with pilots from various squadrons including A, B, D, and E.

An additional 20 Horsas assigned to the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade flew from Royal Air Force Tarrant Rushton, towed by aircraft from No. 298 Squadron and No. 644 Squadron. These gliders carry 20 jeeps, 10 trailers, 10 6-pounder anti-tank guns, 16 motorcycles, and 74 men, all from the Polish Anti-Tank Battery. The pilots come from a mix of squadrons, including A, C, and G.

Of the thirty-five Polish gliders leaving Great Britain, thirty-four gliders reach the designated landing zone with one Polish glider from the Anti-Tank Battery, forced to land in Belgium. Despite the danger, the pilots maintain their course, releasing the thick nylon tow ropes from the gliders at the precise moment over the target area. As the gliders approach their target, they fly at a higher altitude than the supply aircraft, making them less vulnerable to flak. However, as they descend, they are met with a barrage of anti-aircraft fire and small arms fire. The gliders descended at various angles, some catching fire even before they touched down. Jeeps inside the gliders, with their fuel tanks punctured, flooded the aircraft with petrol, and flak turned some into blazing wrecks. Several gliders are hit, though only one is brought down. Its nose is shot off by flak, causing it to crash and eject its cargo of Polish soldiers and a Jeep over the Landing Zone. Other gliders crashed into trees, snapping off their wings, though the passengers and equipment inside remained mostly intact. Out of the 34 gliders reaching the target area, it is believed that 28 successfully land on Landing Zone L.

At that critical moment, something completely unforeseen occurs. From the north, Messerschmitt’s appear, rapidly closing in on the slower-moving Horsas. Their machine guns erupt, filling the sky with gunfire. Several gliders catch fire, spiraling out of control before crashing to the ground. Others are forced to land with damaged undercarriages, their torn fuselages, and broken rudders visible from a distance. One glider disintegrates in mid-air, scattering a jeep, an anti-tank gun, and personnel as it breaks apart. The severity of the attack is far beyond what anyone anticipated.

Two British gliders mistakenly land three kilometres away on Landing Zone S, which has already been overrun by German forces. These gliders should have landed during the Second Lift, and their pilots had not been informed that the Third Lift was designated for a different zone. While one group may have managed to slip away and rejoin friendly forces, the other, part of the 7th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers Mortar Group, is quickly surrounded and taken prisoner.

Although the 7th Battalion is unable to prevent the Germans from firing at the gliders while they are in the air, the gliders manage to land without interference once they descend below the tree line. Unfortunately, many gliders land heavily, damaging much of their equipment. Polish soldiers who survive the Messerschmitts’ assault and manage to land quickly disembark and begin unloading their gliders. However, the Messerschmitts continue to circle above the landing zone, strafing it with machine-gun fire. As they withdraw, German infantry, advancing rapidly from the surrounding forest, press forward towards the landing area. The numerically superior German forces engage the British defenders, pushing them back and ultimately taking control of the landing ground.

Upon landing, the Polish troops acted quickly. Using explosive charges, they blew off the tails of the gliders to unload the guns and vehicles stowed inside. The Germans, having initially focused their fire on the incoming aircraft, then redirected their artillery and machine guns towards the landing troops. The Poles had to dodge intense enemy fire to get off the exposed landing zone, and in some areas, they engaged in direct combat with German infantry.

The German troops then turn their fire on the surviving gliders, riddling them with bullets that tear through the wooden frames, vehicles, and men. The soldiers who remain unscathed are forced to flee to escape the overwhelming enemy assault, which has caught them completely off guard.

Although eight guns had initially landed, it is believed that only three of the ten anti-tank guns are successfully unloaded. One of these guns is commandeered by an officer, reportedly from the 10th Parachute Battalion, and is never seen again. Two others manage to reach Oosterbeek through Wolfheze under the command of 2nd Lieutenant W. Mleczko. Here the two anti-tank guns and their crews join the first troop, which landed one day earlier, and take positions near Hotel Hartenstein. This brings the Polish anti-tank battery to 7 guns and 44 men and their accompanying Glider Pilots. Another two jeeps with trailers, and their crews are unloaded. Their whereabouts are unknown. But most likely they joined the anti-tank battery.

Additionally, Major-General Sosabowski’s personal jeep is flown in and safely unloaded, but it is intercepted by German forces en route to Oosterbeek. The driver is wounded and captured, and when the Germans discover a suitcase bearing Sosabowski’s name, they falsely broadcast that he is killed. The landing is costly, with nine of the 93 Polish personnel either killed or fatally wounded.

| Parachute Group of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade |

On the morning of the scheduled departure, set for 10:00 hours, Major-General Sosabowski instructs his troops to be ready by 09:30 hours. The day starts off dull and foggy, but based on past experience, they expect the weather to clear as the morning progresses. As Sosabowski drives through the airfield with his aide, they become part of a vast military operation, working to organise and bring order to the chaotic scene. Jeeps weave between parked aircraft, which loom out of the mist, while groups of soldiers lift heavy containers into the bomb bays of the planes. Parachutes, helmets, haversacks, and weapons are laid out in neat rows on the ground. Y.M.C.A. vans serve tea, chocolate, and cigarettes to the troops, while American airmen, identifiable by their bright scarves, attempt to converse with the Polish soldiers, despite the language barrier.

Meanwhile, engineers carry out last-minute adjustments to the aircraft engines, ensuring everything is ready for departure. Occasionally, gusts of wind from the propellers send helmets and jump smocks skidding across the airfield, with soldiers chasing after them. Sosabowski’s driver brings the vehicle to a stop near the headquarters aircraft, where fellow passengers are gathered, eager for any updates on the situation.

They ask questions about the weather clearing and their chances of taking off, but Sosabowski offers only a brief response, explaining that he is still awaiting the latest weather report.

After ensuring that his own equipment is in order, Sosabowski continues to drive around the airfield, stopping to check in with the troops, offering words of encouragement and observing the preparations being made for the mission.

As the hours drag on, Sosabowski and the others keep glancing at the sky, watching for any signs of improvement in visibility. Ten o’clock comes and goes, and still, the fog clings to the ground. By midday and then 13:00 hours, there is little change. A weather reconnaissance plane takes off and circles the airfield, but returns without any signs of better conditions.

At around 15:00 hours, the Station Commander approaches Major-General Sosabowski with an apologetic tone, informing him that due to the weather conditions, the mission will not proceed that day. He suggests they try again the following morning at 10:00 hours.

Fortunately, Sosabowski has not sent the lorries back to camp, allowing his staff to swiftly organise the return of the troops to their billets. Later, as he sits in his office, Colonel Stevens arrives with concerning news. He informs Sosabowski that the second glider lift, which had taken off earlier that morning from Down Ampney and Tarrant Rushton, had better weather conditions. However, there is an unconfirmed report suggesting that the gliders may have been destroyed by German forces during the landing.

The news hits Sosabowski hard, leaving him momentarily stunned, as thoughts of his worst fears surface. Yet, despite the alarming initial report, the reality of the situation is not quite as severe as it first appears.

By 17:00 hours, the complete paratrooper lift returns to the garrison areas around Stamford to prepare for the rescheduled take-off the following day.

| Multimedia |