| Page Created |

| November 8th, 2023 |

| Last Updated |

| August 13th, 2025 |

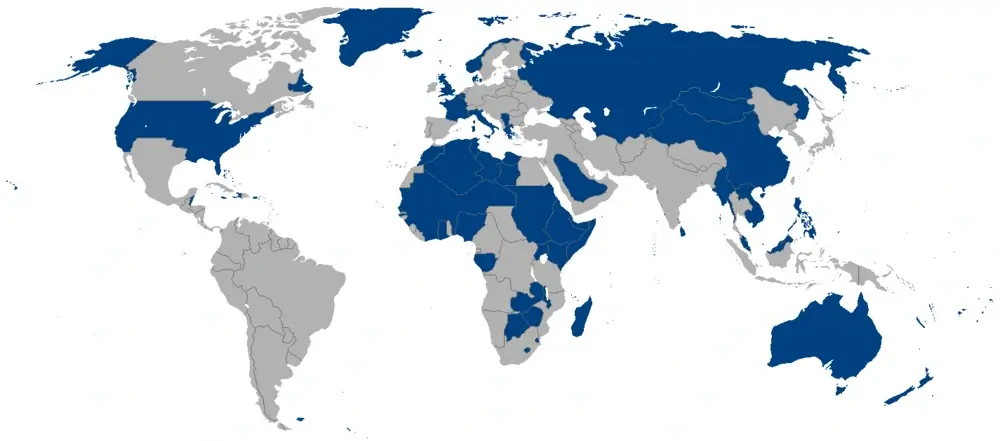

| Allied Countries |

|

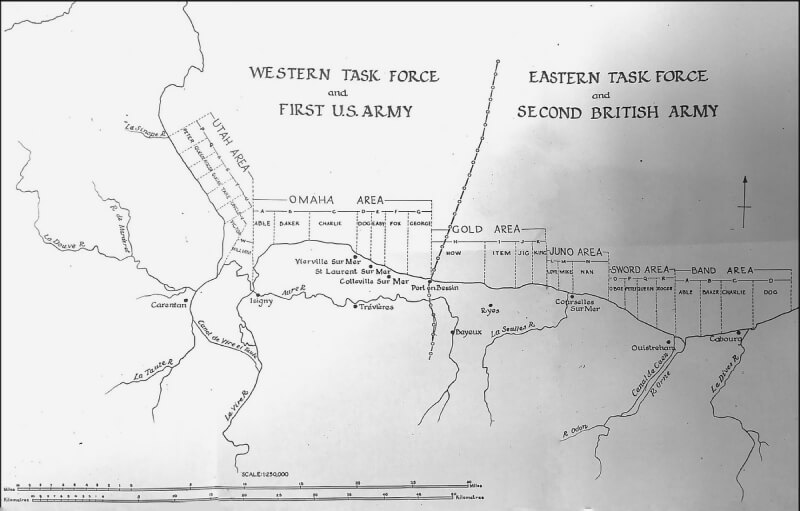

| Operational Areas |

| Special Forces Operation Neptune 6th Airborne Division Band Beach Sword Beach Gold Beach Juno Beach Omaha Beach Utah Beach 82nd Airborne Division 101st Airborne Division |

| Related Operations |

| Operation Gambit Operation Neptune Operation Perch Operation Cobra Operation Epsom Operation Charnwood Operation Atlantic Operation Goodwood Operation Bluecoat Operation Totalize |

| June 4th, 1944 – July 3rd, 1944 |

| Operation Neptune |

| Objectives |

- To mount and carry out an operation with forces of the Allied Expeditionary Force to secure a lodgement on the Continent from which further offensive operations can be developed.

| Operational Area |

| Allied Forces (Assault Phase) 21st Army Group |

| British Second Army |

- 79th Armoured Division

- Special Air Service, Brigade

- 1st Special Service Brigade

- 4th Special Service Brigade

- East of the Orne River

- 6th Airborne Division

- Sword Beach

- 3rd British Infantry Division

- 27th Armoured Brigade, 79th Armoured Division

- Juno Beach

- 3rd Canadian Infantry Division

- 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade

- 5th Assault Regiment, Royal Engineers, 79th Armoured Division

- 22nd Dragoons, 79th Armoured Division

- Gold Beach

- 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division

- 8th Armoured Brigade, 79th Armoured Division

| U.S. First Army |

- Omaha Beach

- 1st Infantry Division

- 741st Tank Battalion

- 29th Infantry Division

- 743rd Tank Battalion

- 2nd Ranger Battalion

- 5th Ranger Battalion

- Pointe du Hoc

- 2nd Ranger Battalion

- Utah Beach

- 4th Infantry Division

- 70th Tank Battalion

- 82nd Airborne Division

- 101st Airborne Division

| Allied Forces (D+10) 21st Army Group |

| British Second Army |

- 7th Armoured Division

- 51st (Highland) Infantry Division

- 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division

- 4th Canadian Armoured Division

| U.S. First Army |

- 2nd Infantry Division

- 90th Infantry Division

- 9th Infantry Division

- 2nd Armored Division

- 3rd Armored Division

| Axis Forces, 7. Armee |

| LXXXIV. Armee-Korps |

- 91. Luftlande-Infantrie-Division

- 243. Infanterie-Division

- 319. Infanterie-Division

- 352. Infanterie-Division

- 709. Infanterie-Division

- 716. Infanterie-Division

| 15. Armee Panzergruppe West I. SS-Panzerkorps |

- Schwere SS-Panzer-Abteilung 101

- 1. SS-Panzer-Division “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler”

- 12. SS-Panzer-Division “Hitlerjugend”

- 17. SS-Panzer-Division “Götz von Berlichingen”

| 15. Armee Panzergruppe West LVIII. Reserve-Panzerkorps |

- 130. Panzer-Lehr-Division

- 16. SS-Panzer-Division “Reichsführer SS”

- 21. Panzer-Divisi

| Operation Neptune |

Operation Neptune, designated as the assault phase of Operation Overlord, played a pivotal role in the liberation of north-west Europe. Indeed, its name was fittingly chosen. While recognizing the invaluable contributions of other services, it’s important to note that the Navy was primed to take a central role in the initial stages, particularly in convoy and transport operations.

Operation “Neptune” can be distinctly categorised into three phases:

- Preparation and Planning (May 1942 – June 1944).

- Execution, which includes the Assault Landings (June 4th – 6th, 1944).

- Consolidation and Build-up (June 7th, 1944- July 3rd, 1944).

However, this operation was unique in two specific aspects. First was the close proximity of the Great Britain, serving as the main base. This proximity enabled the maximal use of Allied Sea and Air superiority, quick turnaround times for build-up shipping, and innovative measures such as prefabricated harbours and submarine pipeline oil supplies. Second was the operation’s sheer magnitude in conception and execution.

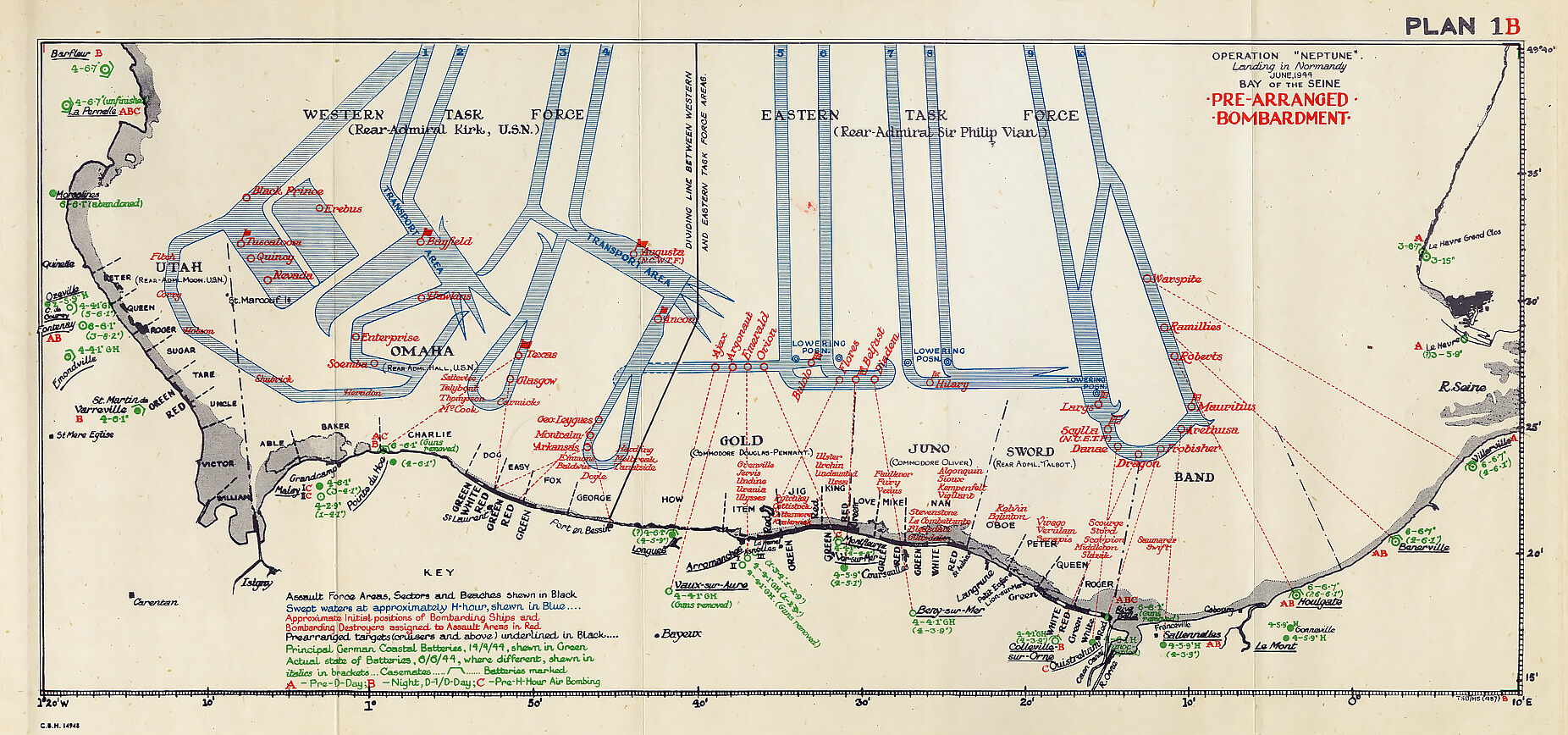

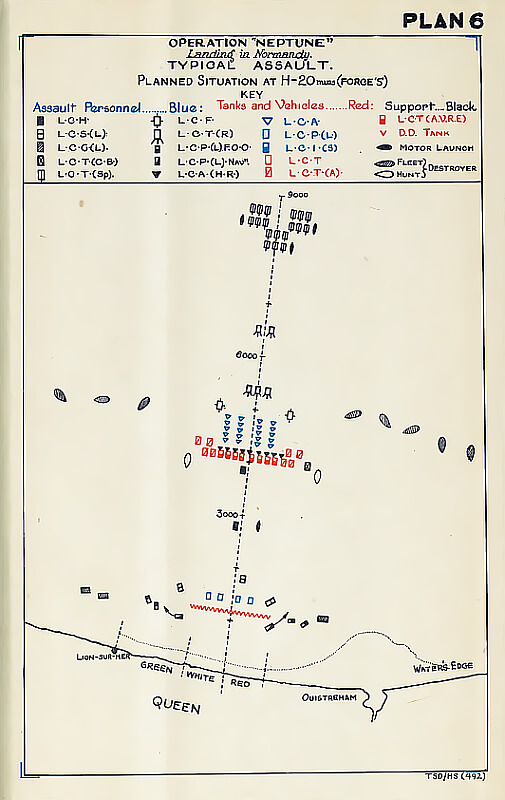

The operation involved landing five divisions, complete with their stores, motor transport, and equipment, onto open beaches fortified with modern defensive technology. Following the establishment of the initial bridgehead, the focus shifted to rapidly increasing the force to about thirty divisions and ensuring their continual support. The first four days alone saw the involvement of over 5,000 ships and crafts. Coordinating such a large armada demanded meticulous attention to loading and berthing arrangements, movement coordination, security measures against enemy interference and weather conditions, efficient disembarkation processes, and ongoing reinforcement and supply flow. Additionally, it involved providing direct support to the Army through bombardment efforts.

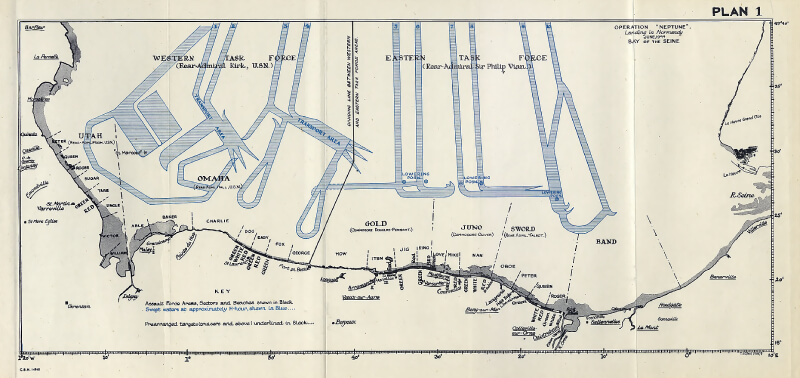

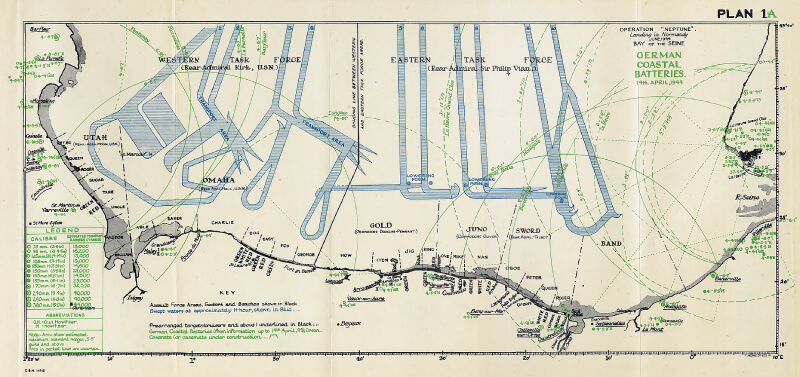

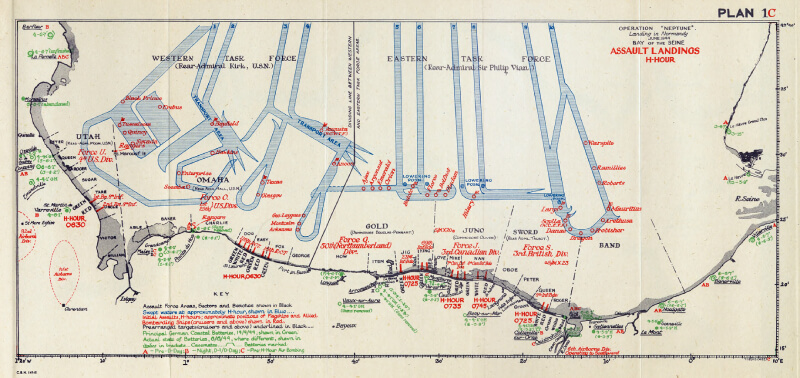

The invasion beaches are named following an Allied code-naming system, which assigned American landing sites names of U.S. cities and States, these code names are chosen for its simplicity and ease of recognition over radio communications. Omaha Beach, alongside Utah Beach, are the codenames for the beaches assigned to the American forces. The origin of the name Omaha is traced back to the city of Omaha, Nebraska. The name Utah to the State Utah in the United States.

The British beaches bore code names of fish and birds. In Operation Overlord and Neptune, they are originally called Goldfish, Jellyfish, Swordfish, and Bandfish, but the Canadians objected to landing on a beach named Jelly, leading to its renaming to Juno. Jelly is apparently, changed to Juno in honour of the wife of one of the officers. Consequently, the fish-themed names are dropped by the British, leaving the names Gold, Sword, and Band.

| Multimedia |

| Multimedia |

| April 1st, 1944 |

A strict visitors’ ban is imposed within a 16-kilometre zone of the south coast of England. This measure is implemented as part of broader security efforts to prevent leaks of information regarding the upcoming Allied invasion of Western Europe. Civilians are required to carry permits, and movement into the coastal area is closely monitored by military authorities.

| April 17th, 1944 |

A ban on all foreign diplomatic and courier movements to and from Great Britain is enacted. The British government, with full Allied cooperation, introduces this unprecedented measure to limit the possibility of espionage or unintended disclosures concerning Operation Overlord. Diplomatic personnel are either confined to London or recalled, and no official communications are permitted to leave British territory.

| April 26th, 1944 |

Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, appointed Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force, relocates his headquarters from London to Southwick House near Portsmouth. This Victorian manor house, designated as Southwick Park, is selected due to its secure inland location, extensive communications facilities, and proximity to embarkation ports. From this new headquarters, Ramsay oversees the final stages of planning for the naval component of Operation Neptune.

Exercise “Tiger” takes place in Lyme Bay, off the coast of Devon. This large-scale full rehearsal of the Utah Beach landing is conducted by Force “U”, consisting primarily of elements from the U.S. VII Corps, including the 4th Infantry Division. The exercise is intended to replicate landing procedures, embarkation timing, and fire support coordination in a realistic operational environment.

In naval action off the Île de Batz, German torpedo boat T.29 is engaged and sunk by the Canadian destroyer H.M.C.S. Haida. T.29, a Type 39 torpedo boat, is destroyed during a night action as part of Allied operations to suppress German surface raiders in the western English Channel. The engagement confirms the growing dominance of Allied naval forces in coastal waters.

Later the same day, torpedo boat T.27, a sister ship to T.29, is also intercepted by H.M.C.S. Haida and driven ashore near Pontusval, Brittany. The vessel is set ablaze by shellfire and rendered a total loss. The back-to-back engagements highlight the Royal Canadian Navy’s aggressive patrolling tactics and effectiveness in coastal interdiction.

However, in the same series of actions, H.M.C.S. Athabaskan, another Canadian Tribal-class destroyer, is struck by a torpedo, likely from German torpedo boat T.24, and sinks with heavy loss of life. The attack takes place off the coast of Brittany during a return patrol. Of her crew, 128 are killed and eighty-five taken prisoner. The loss marks one of the most tragic single-ship losses for the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War.

| April 28th, 1944 |

Disaster strikes Exercise Tiger in the early hours of the morning when a flotilla of German E-Boats (Schnellboote) from Cherbourg slips past Allied naval screens and attacks Convoy T-4. The convoy, consisting of Landing Ship, Tanks transporting troops and vehicles, is ambushed under cover of darkness.

LST 507 and LST 531 are both torpedoed and sunk, while LST 289 is heavily damaged.

A total of 749 American servicemen are killed, including many from the 3206th Quartermaster Service Company and the 1st Engineer Special Brigade. The disaster is kept secret for weeks to preserve operational morale and maintain secrecy ahead of D-Day.

| May 2nd, 1944 |

The Allies conduct Exercise “Fabius”, the largest amphibious training operation of the Second World War. Split across multiple beaches, Fabius I and II involve Force “O”, assigned to Omaha Beach, rehearsing landings in Lyme Bay. Fabius III to V, involving the Eastern Task Force, rehearse landings near the Isle of Wight and Hayling Island.

These full-scale rehearsals include live fire, simulated enemy resistance, naval gunfire support, and embarkation drills. The exercises are critical in correcting procedural errors noted during Exercise Tiger, especially in embarkation discipline and landing sequences. Weather disruptions and timing refinements provide valuable operational insight. Allied command treats these events as the final verification of readiness. The exercise lasts until May 6th, 1944.

| May 8th, 1944 |

Following updated meteorological reports and strategic briefings, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay convenes senior staff at Southwick House and determines that June 5th, 1944 or June 6th, 1944 offers the most favourable window for D-Day.

This decision accounts for tide conditions, moonlight for airborne operations, and weather forecasts over the Channel. The decision is provisional and subject to final meteorological approval nearer the date.

| May 12th, 1944 |

The Naval Assault Plan for Operation Neptune is officially frozen. No further amendments to beach assignments, timings, landing craft loading orders, or fire support schedules are permitted. All units involved receive final versions of their operational plans.

This “freezing” of the plan marks the conclusion of over a year of combined planning and enables final loading, dissemination, and rehearsals to begin in earnest across all embarkation areas.

| May 21st, 1944 |

King George VI visits key embarkation ports in southern England, including Southwick House and Portsmouth Naval Base.

He is briefed on the final stages of Operation Overlord by Admiral Ramsay and General Eisenhower and inspects elements of the Royal Navy, Canadian forces, and the Eastern Task Force. His visit boosts morale and is kept secret for security reasons.

| May 22nd, 1944 |

A practice mobilisation of 80 accredited war correspondents is carried out by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. The press corps includes British, American, and Canadian reporters who are to accompany the invasion forces and report from the beachheads once a secure lodgement is achieved.

They are issued uniforms, rations, identity cards, and sealed orders. The exercise familiarises them with embarkation protocols and signals the nearing of the invasion.

| May 24th, 1944 |

German torpedo-boat Grief, part of the Kriegsmarine’s 5th Torpedoboot Flotilla, is damaged by an air attack from No. 415 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, near the mouth of the River Orne.

Shortly after, Grief collides with her sister-ship Falke and sinks. During the same sortie, another German vessel, Kondor, strikes a mine and is severely damaged. These actions form part of sustained Allied aerial and naval pressure against German coastal patrol units along the Normandy coast.

| May 25th, 1944 |

At 23:30, sealed operational orders are opened by designated Allied commanders across Southern England.

The full written orders for Operation Neptune and the initial assault phase of Overlord are now in the hands of corps, divisional, and brigade-level officers. Naval task force commanders receive final confirmation of fire support tasks, landing timings, and communications schedules. The countdown to D-Day has effectively begun.

| May 26th, 1944 |

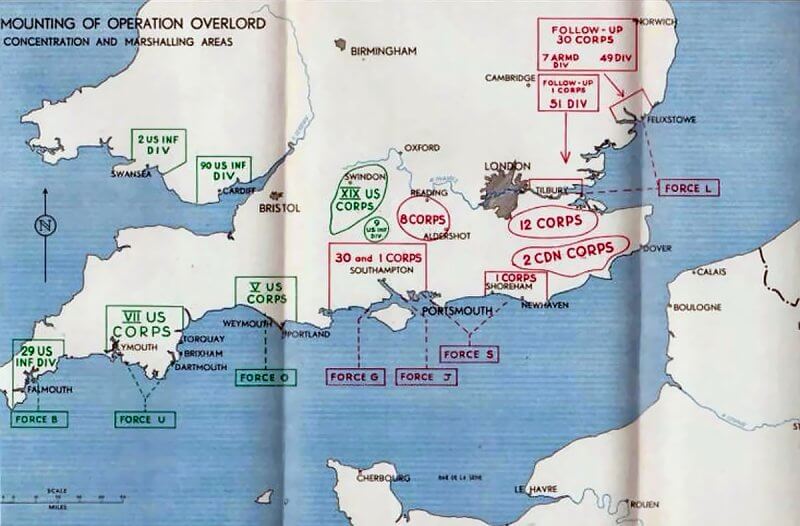

The assault troops of Operation Overlord have completed their final phase of intensive training. Units now begin moving from inland concentration areas towards their assigned marshalling camps near the ports of embarkation. These are sealed, enclosed facilities. From the moment of arrival, troops are cut off from the outside world to preserve operational secrecy.

| May 27th, 1944 |

Detailed briefings begin. Until this point, only commanding officers and a single staff officer per unit have been fully informed of the invasion plan. Now, company commanders are brought into the picture. On D-3, the briefings are extended to junior officers and non-commissioned officers. With each layer of leadership informed, preparations move rapidly towards final readiness.

Units are then reorganised into their designated assault groups. Considerable effort has gone into ensuring that every soldier knows his exact role, both for the initial landing and for the critical follow-up phase. Realism and precision are key. Intricate terrain models, aerial photographs, maps, and rehearsals are used extensively. All feature code-names in place of real geographical references. The true objective remains classified to preserve the element of surprise.

Even at this late stage, troops are not told where they will land. Only after boarding their assault ships are the actual beach maps distributed.

| May 28th, 1944 |

June 5th, 1944, is formally nominated as “D-Day”, pending final weather confirmation.

At the same time, all naval personnel are “sealed in” aboard their assigned ships and craft. Communications with the outside world are cut off. No one is permitted to disembark, and all mail is withheld. This extreme security measure ensures that no information concerning the invasion’s timing, targets, or troop movements can leak.

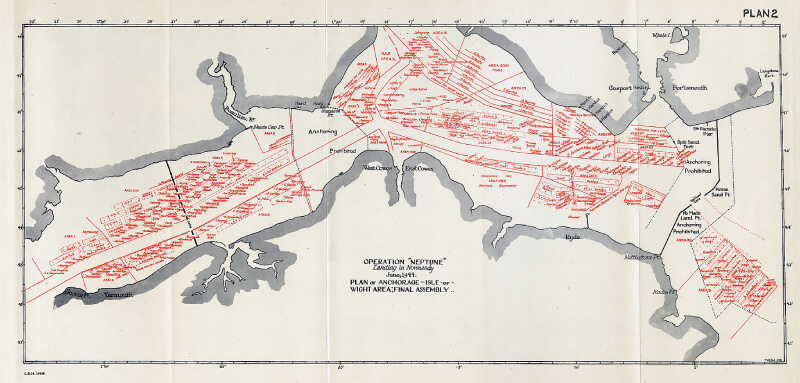

The entire invasion armada, now numbering over 6,900 vessels, is ready for the final embarkation of troops, vehicles, ammunition, fuel, and supplies under tight discipline and silence.

| June 1st, 1944 |

Final embarkation operations are underway across the entire south coast of England. Troops, vehicles, and supplies continue to load under strict security. All naval personnel remain sealed within their assigned ships, unable to disembark or communicate with the outside world.

The Allied naval armada is now concentrated in dozens of ports, hards, and anchorages from Falmouth to Harwich, awaiting final orders.

| June 2nd, 1944 |

Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay formally assumes general operational control of all Allied naval forces in the English Channel. As Allied Naval Commander, he directs all sea movements, including convoys, bombardment groups, minesweepers, escorts, and landing craft under Operation Neptune, the naval phase of Overlord.

The same day, Bombarding Force O of the Eastern Task Force (ETF) departs Scapa Flow. It consists of two battleships, one monitor, five cruisers, and eight fleet destroyers. This formation is tasked with supporting the Omaha Beach assault by neutralising German coastal batteries prior to the landings.

Onboard, final confirmatory briefings for all soldiers take place. These include the names and layouts of the real landing zones.

| June 3rd, 1944 |

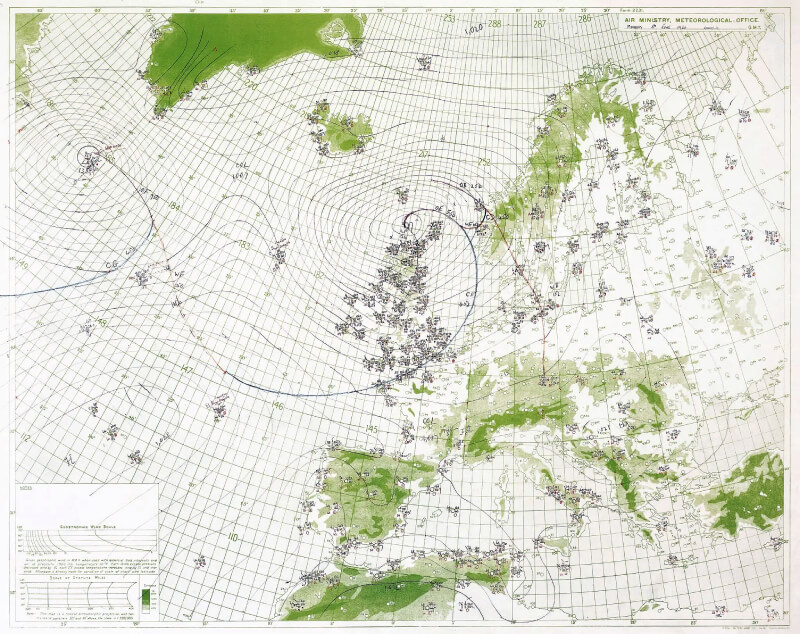

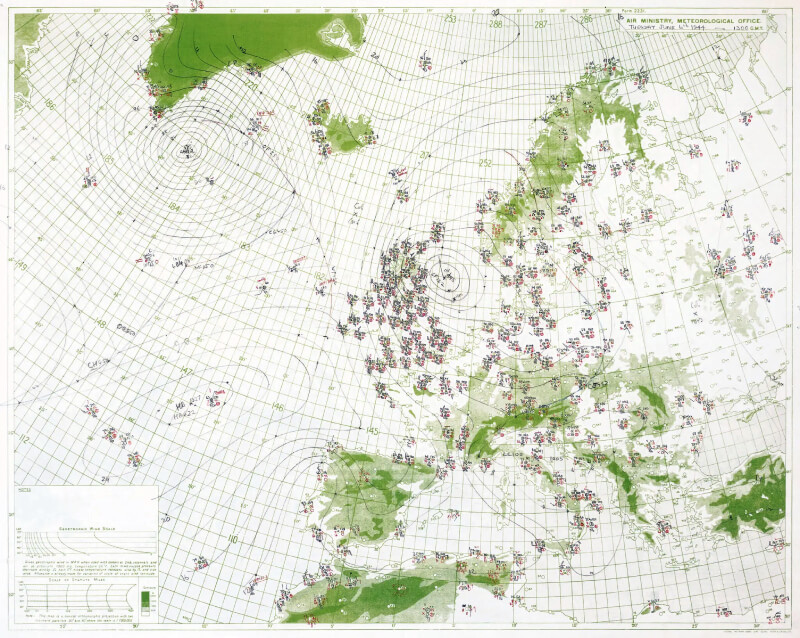

Final weather forecasts suggest deteriorating conditions in the Channel, raising concerns among Allied planners.

Meanwhile, two midget submarines, X.20 and X.23, are towed out of Portsmouth. These vessels are assigned to mark landing sectors with beacon lights and sonar signals. X.20 is designated for the Juno sector, and X.23 for the Sword sector. Their crews operate under strict radio silence and are scheduled to arrive off the French coast hours before H-Hour.

Two X-class midget submarines, X.20 and X.23, are towed out from Portsmouth to mark the Juno and Sword beach sectors using sonar and beacon signals. Meanwhile, minesweeping flotillas, begin clearing German-laid minefields. As they continue clearing safe channels, the risk of early German detection increases. Yet no German response comes. Believing the weather too severe for invasion, German commanders remain passive. The minesweepers cannot be recalled. Their task once underway is irreversible.

| June 4th, 1944 |

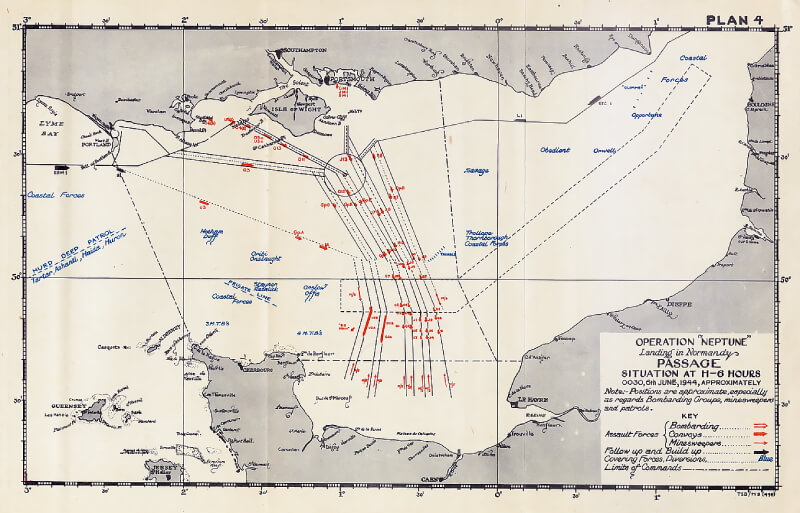

During the morning, the opening phase of Operation Neptune, the naval component of the Allied invasion of Normandy, is fully underway. More than 6,000 vessels, including warships, landing craft, transports, minesweepers, and support ships, are either at sea or preparing to depart from ports along the southern coast of England.

The assault convoys for each beach sector are assembling or already en route to mid-Channel staging areas. Force U, carrying the U.S. 4th Infantry Division for the Utah Beach assault, has departed from Start Point in Devon. Force O, bound for Omaha Beach, has sortied from the ports of Portland and Weymouth. Force G, assigned to Gold Beach, is underway from Tor Bay. Forces J and S, assigned to Juno and Sword Beaches respectively, are preparing to sail from Southampton, Portsmouth, and Newhaven.

During the afternoon, the weather across the Channel begins to deteriorate. A low-pressure system moves in, bringing strong winds, heavy seas, and low cloud cover. Conditions are judged unsuitable for an amphibious assault. Visibility is poor, surf conditions are worsening, and air support is unlikely to operate effectively. Naval gunfire would be unreliable.

At 21:00 hours, in the underground operations room at Southwick House, General Dwight D. Eisenhower convenes his senior commanders. Southwick House, is the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, the nerve centre of Operation Overlord, the Allied plan to liberate Nazi-occupied Europe. The invasion fleet is already at sea. More than 5,400 assault craft, supported by 156,000 troops, are underway or preparing to sail. Operation Overlord with landings on June 5th, 1944, has begun.

Chief meteorologist Group Captain James Stagg delivers the critical forecast: high winds and poor conditions will persist into the next morning. Stagg warns that landing operations would be too dangerous. Naval gunfire support could fail. Air cover might not arrive on time.

Captain Stagg gives the Commanders the worst report you ever saw. Gales hitting the Normandy beaches. Winds up to forty-five miles an hour. Landing impossible. General Dwight D. Eisenhower decides “All right, we’ll postpone. Twenty-four hours.”

However, throughout the day, however, a new forecast began to emerge. Group Captain James Stagg, the chief meteorological adviser, now presented an updated forecast. Despite the prevailing poor weather, a brief window of relatively good conditions was predicted for the early morning of Tuesday, 6th June. Winds would ease, seas would moderate, and cloud cover would lift sufficiently to permit both naval and airborne operations, though just for a short period.

As the storm continued to batter the English coast and the Channel remained turbulent, General Dwight D. Eisenhower convened a critical conference in the main operations room of Southwick House. Present were Admiral Ramsay, General Montgomery, Air Chief Marshal Tedder, Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, and General Walter Bedell Smith.

Debate followed. Concerns were raised about visibility, the surf conditions on the beaches, and the reliability of air support. Stagg’s team could not guarantee a second opportunity before mid-June. The alternative to seizing this brief window was to stand down the invasion force for days, or even weeks, risking German detection, declining morale, and logistical chaos.

After listening to the views of his commanders, Eisenhower fell silent for a moment. Then, with characteristic calm and resolve, he made his decision:

“Well, I am quite positive we must give the order; the only question is whether we should meet again in the morning.

Well, I don’t like it but there it is.

Well boys, there it is, I don’t see how we can possibly do anything else.”

Thanks to the persistence and judgement of the meteorological staff, a narrow but vital window had been identified. General Eisenhower jokingly promises Stagg and fellow forecaster Dr. Yates a bottle of whisky if the forecast proves correct.

With some optimism returning, the assault is provisionally reinstated for 06:30 on Tuesday, June 6th, 1944. This decision, however, remains conditional, final confirmation will be required at the early morning conference on June 5th, 1944.

The order to halt Operation Neptune goes out immediately. But it is already too late to stop much of the vast Allied armada now moving through the Channel. Dozens of convoys are already underway or preparing to sortie from English ports.

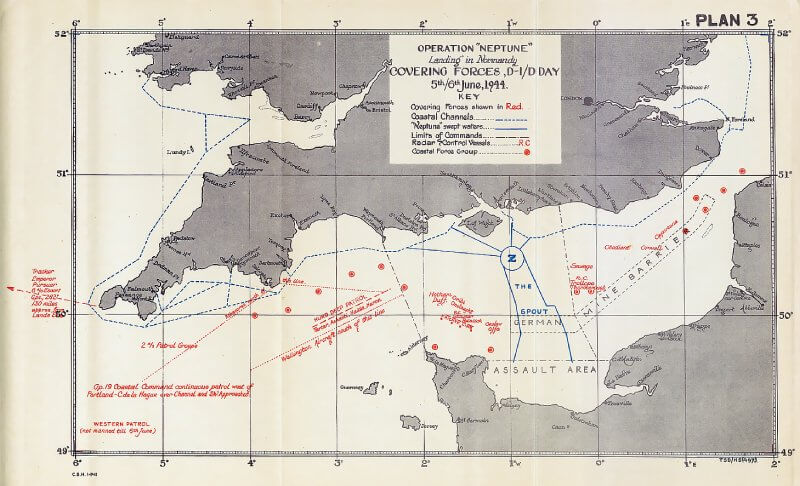

Radio silence is maintained. Coded recall signals, prearranged short-code messages, are sent to escort commanders and lead vessels. Ships at sea reduce speed, hold station, or begin slow circular movements in mid-Channel assembly zones, designated “Z” sectors on naval charts.

Convoy UT-1, toward Utah Beach, halts south of Start Point.

Convoy OB-1, bound for Omaha Beach, slows west of Portland Bill.

Convoy G-1, heading for Gold Beach from Tor Bay, receives new holding orders.

The recall does not reach all craft at once. Conditions at sea are punishing. Destroyers maintain navigational discipline and spacing as troops huddle in cramped quarters. For the men aboard, the delay is physically and psychologically punishing. Many troops have been confined to their ships since June 1st, 1944, under sealed orders and without outside communication. Letters are forbidden. Meals are cold. Sanitary facilities are crude. Seasickness is widespread. No explanation is given for the delay, and morale begins to fray.

Back at Southwick House, Eisenhower faces another dilemma. Ultra intelligence confirms that the German 91. Infanterie-Division has redeployed into the planned drop zones of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division. One grim forecast predicts that over half the paratroopers could become casualties in the opening hours.

That evening, Eisenhower sits alone in his trailer near the command compound. The weight of the decision is his alone.

| Multimedia |

| June 5th, 1944 |

By 03:30 General Eisenhower returns to Southwick House. The room is quiet. Everyone waits. Eisenhower sits down silently. Maybe thirty-five, forty-five seconds. Others say it was five minutes. General Eisenhower gets up and says, ‘Okay, we’ll go.’ And the room cleared in seconds. That’s the most terrible moment for a commander. There’s nothing more he can do once it starts.”

Orders go out immediately. At 05:15, Bombarding Forces E and K of the Eastern Task Force depart from the Clyde. This group includes one battleship, seven cruisers, and twelve destroyers. Bombarding Forces A and C of the Western Task Force depart Belfast with three battleships, a Royal Navy monitor, nine cruisers, and seventeen destroyers.

Force U resumes full speed towards the Cotentin Peninsula. Other task forces follow from their anchorages.

At 19:57, Eisenhower’s decision is officially transmitted down the chain of command: D-Day is set for 6 June.

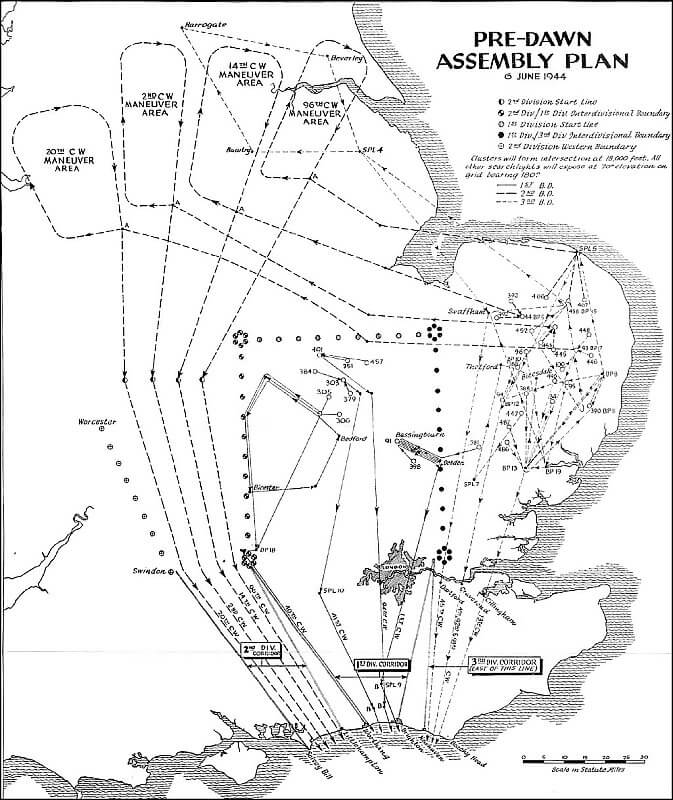

That evening, General Eisenhower visits the U.S. airborne troops at their departure airfields. The men of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions are already gearing up, faces camouflaged, weapons packed. Their mission is to secure the flanks of the invasion front before dawn.

By 23:00, the first waves of the Eastern Task Force, carrying British and Canadian assault troops, depart the Solent. Western Task Force convoys are already deep in the Channel. Behind them stretch the follow-up echelons and support craft.

| Multimedia |

| Sources |