| Page Created |

| November 8th, 2023 |

| Last Updated |

| August 24th, 2025 |

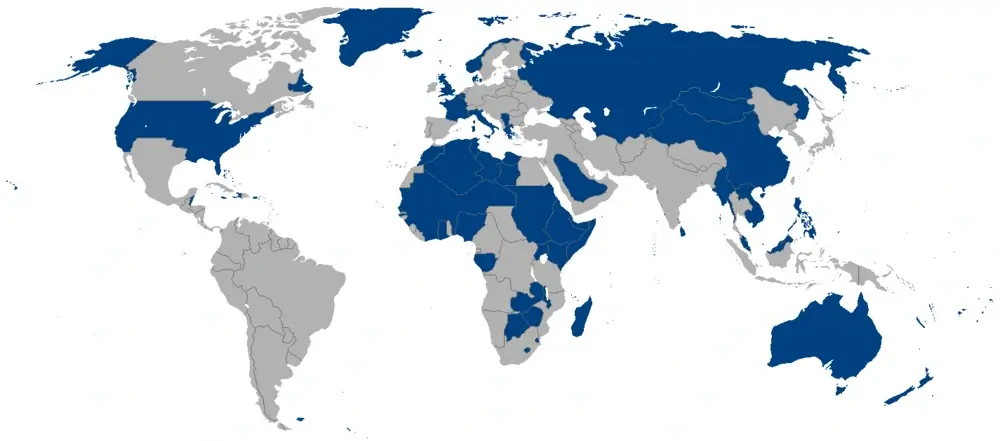

| Allied Counties |

|

| Related Operations |

| Operation Gambit Operation Neptune Operation Perch Operation Epsom Operation Charnwood Operation Atlantic Operation Goodwood Operation Bluecoat Operation Totalize |

| Operational Areas |

| Special Forces Operation Neptune 6th Airborne Division Band Beach Sword Beach Gold Beach Juno Beach Omaha Beach Utah Beach 82nd Airborne Division 101st Airborne Division |

| June 5th, 1944 – August 19th, 1944 |

| Operation Overlord |

| Objectives |

- To mount and carry out an operation with forces of the Allied Expeditionary Force to secure a lodgement on the Continent from which further offensive operations can be developed.

- This strategic area must have adequate port facilities to maintain a force of 26 to 30 divisions. Furthermore, it is essential for this position to support the augmentation of this force by follow-up formations at a rate of three to five divisions per month.

| Operational Area |

| Allied Forces (Assault Phase) 21st Army Group |

| British Second Army |

- 79th Armoured Division

- Special Air Service, Brigade

- 1st Special Service Brigade

- 4th Special Service Brigade

- East of the Orne River

- 6th Airborne Division

- Sword Beach

- 3rd British Infantry Division

- 27th Armoured Brigade, 79th Armoured Division

- Juno Beach

- 3rd Canadian Infantry Division

- 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade

- 5th Assault Regiment, Royal Engineers, 79th Armoured Division

- 22nd Dragoons, 79th Armoured Division

- Gold Beach

- 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division

- 8th Armoured Brigade, 79th Armoured Division

| U.S. First Army |

- Omaha Beach

- 1st Infantry Division

- 741st Tank Battalion

- 29th Infantry Division

- 743rd Tank Battalion

- 2nd Ranger Battalion

- 5th Ranger Battalion

- Pointe du Hoc

- 2nd Ranger Battalion

- Utah Beach

- 4th Infantry Division

- 70th Tank Battalion

- 82nd Airborne Division

- 101st Airborne Division

| Allied Forces (D+10) 21st Army Group |

| British Second Army |

- 7th Armoured Division

- 51st (Highland) Infantry Division

- 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division

- 4th Canadian Armoured Division

| U.S. First Army |

- 2nd Infantry Division

- 90th Infantry Division

- 9th Infantry Division

- 2nd Armored Division

- 3rd Armored Division

| Allied Forces (July 1944) 21st Army Group |

| British Second Army |

- 59th (Staffordshire) Infantry Division

- 11th Armoured Division

- 33rd Armoured Brigade

| U.S. First Army |

- 8th Infantry Division

- 79th Infantry Division

- 35th Infantry Division

- 4th Armored Division

- 6th Armored Division

| Axis Forces, 7. Armee |

| LXXXIV. Armee-Korps |

- 91. Luftlande-Infantrie-Division

- 243. Infanterie-Division

- 319. Infanterie-Division

- 352. Infanterie-Division

- 709. Infanterie-Division

- 716. Infanterie-Division

| 15. Armee Panzergruppe West I. SS-Panzerkorps |

- Schwere SS-Panzer-Abteilung 101

- 1. SS-Panzer-Division “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler”

- 12. SS-Panzer-Division “Hitlerjugend”

- 17. SS-Panzer-Division “Götz von Berlichingen”

| 15. Armee Panzergruppe West LVIII. Reserve-Panzerkorps |

- 130. Panzer-Lehr-Division

- 16. SS-Panzer-Division “Reichsführer SS”

- 21. Panzer-Divisi

| Operation |

Allied intelligence preparations for a European counter-invasion begin in 1941. British analysts commence a general study of occupied Europe. In October that year, Prime Minister Winston Churchill recalls Lord Louis Mountbatten from the Fleet. Mountbatten is appointed head of Combined Operations Headquarters. His mandate is clear and urgent.

Churchill orders him to prepare for the major counter-invasion of Europe. He states that unless overwhelming Allied forces can land and defeat German troops in France, Hitler will remain undefeated. The task is offensive, not defensive. Mountbatten is to formulate an invasion doctrine, create new landing craft and equipment, and ensure inter-service cooperation across the Army, Navy, and Air Force. Churchill directs that while others defend, Mountbatten’s team must think only of attack.

Upon assuming his role, Mountbatten begins to develop a doctrine for the Second Front. He defines three essential elements for success. First, the Allies must secure a firm lodgement on a chosen section of enemy coastline. This must be achieved despite all known defences.

Second, the Allies must rapidly expand their beachhead while reinforcements and supplies flow ashore. These must continue without pause, regardless of weather conditions in the critical early weeks.

Third, German reserves must be delayed or misdirected. Deception operations must draw their attention away from the true landing site. At the same time, Allied bombing must cripple road and rail links. These actions must begin months in advance to slow German reinforcement once the deception is revealed.

| Lessons from Dieppe |

While the German press gloats over the failed Allied raid at Dieppe, Combined Operations Headquarters draws serious conclusions. In October 1942, Mountbatten signs a forthright Combined Report on the Dieppe Raid. The report is widely circulated and closely studied. Lieutenant General Frederick Morgan, Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), uses the findings in his future planning.

The report highlights the most crucial lesson: the need for overwhelming fire support. It declares that no existing naval vessels can adequately support landings at close range. Without such support, any assault on Europe’s fortified coast will likely fail, especially as German coastal defences become more formidable.

Other findings are recorded in the report’s appendices. The cost of Dieppe is high, but the experience proves essential. Lessons learned there, and later in North Africa and Sicily, help shape future invasion planning. Mountbatten later assesses that each casualty at Dieppe saved ten lives in Normandy.

| The COSSAC Planning Phase |

During the early phases of planning for the Second Front, COSSAC’s staff undertakes a detailed analysis of the European coastline. The entire stretch from Norway to the Pyrenees is examined for its suitability to host an Allied amphibious invasion. This extensive study reaches maturity by late 1943. Ultimately, two principal areas are considered: the Pas-de-Calais and the Normandy coast between the Cotentin Peninsula and Caen.

Pas-de-Calais offers many operational advantages. It lies closest to Britain, minimising the time and exposure of sea and air crossings. It provides a direct route into the Ruhr industrial basin,Germany’s economic heart. The region is also well covered by Allied fighter aircraft operating from southern England. However, these same qualities render it the most obvious choice in German eyes. The Germans have therefore fortified Calais with dense defensive belts and significant troop concentrations.

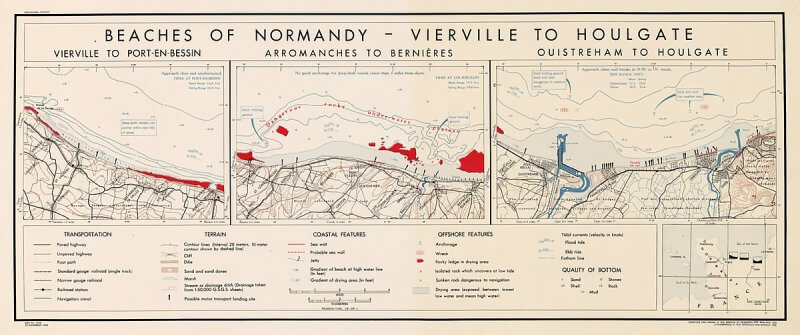

In contrast, the Normandy coastline is less strongly defended. The beaches here are partially shielded by the Cherbourg Peninsula from prevailing westerly winds. This natural protection makes the area well suited for unloading the immense quantities of vehicles, supplies, and reinforcements required to sustain a modern field army. The six-fathom line, which defines the point of deep water near shore, lies close enough to allow large transports and fire support vessels to approach within effective operating distance. The deep-water port at Cherbourg, if captured quickly and intact, offers an ideal entry point for sustaining follow-on operations.

The main drawbacks of Normandy lie in its distance. At roughly 120 kilometres farther from British ports than Calais, it shortens the loiter time of Allied aircraft and lengthens convoy exposure. Nonetheless, the Joint Planning Staff accepts these limitations. The opportunity for operational surprise, reduced enemy strength, and better beach geography outweigh the disadvantages.

For the infantryman, terrain is life. It offers concealment, protection, and opportunities for manoeuvre. Amphibious assaults leave troops painfully exposed between the surf and the first cover. The Allied planners’ understanding of the Baie de la Seine, tidal cycles, and inland terrain is remarkably thorough. Intelligence staff collect data on depth contours, gradients, sand quality, reef locations, and sandbars. The British public contributes pre-war photographs, postcards, and maps. French Resistance operatives gather intricate sketches of enemy positions. These are later displayed in the Caen Memorial Museum. Special Forces, naval personnel, and aerial reconnaissance teams also play a part.

From England, Allied signal units intercept German communications, using Ultra decrypts and electronic surveillance to identify radar sites, artillery batteries, and command nodes. This intelligence is fused into the growing operational picture.

Morgan’s planning team identifies that much of the Normandy coastline in Calvados consists of cliffs, some exceeding 30 metres in height. Inland from the beaches lie flood-prone lowlands. By early 1944, German engineers have flooded these areas deliberately. Behind Utah Beach, the marshes are deepened, isolating the beach causeways. Similar inundations occur in the operational zone of the U.S. 29th Infantry Division between Isigny-sur-Mer and Trévières. The River Aure and its floodplain have been transformed into an anti-vehicle obstacle.

In April 1943, Morgan warns his team that a planning staff must produce more than paperwork. He insists on translating plans into real operational readiness. The following month, Roosevelt and Churchill meet in Washington. Their military advisors agree to launch an assault on the Atlantic Wall in 1944.

The Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander and Combined Operations then develop a detailed military estimate. This appreciation concludes that Normandy is the most suitable site for the landing. These findings are finalised at Conference Rattle. Roosevelt and Churchill endorse the plan at the Quebec Conference (Quadrant) in August 1943. They set a provisional target date of May 1st, 1944. The operation is code-named Overlord.

The Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander’s report makes a critical deduction. The Allies cannot afford to attack a heavily fortified port directly. Nor can they rely on seizing one intact in the early stages. Once the landings begin, German reinforcements will converge on the beachhead. Their aim will be to contain and eliminate the Allied force before it can build sufficient strength.

General Omar Bradley summarises this point aboard U.S.S. Augusta on June 3rd, 1944. He explains that the landings themselves may succeed, but the decisive factor is whether the Allies can sustain and expand them. Success depends on swift reinforcement and supply.

In August 1943, during the Quebec Conference, Allied leaders formally select Normandy as the site for the invasion of Fortress Europe. Once agreed, the plan enters a phase of intense refinement. Service branches and tactical commands each conduct their own assessments, within the confines of operational security.

The Allies know that logistical superiority will determine the outcome. They must not only land troops but keep them supplied with fuel, ammunition, and equipment. Port facilities are therefore essential.

German intelligence is unaware of the Mulberry harbour concept. In the absence of a known Allied alternative, Hitler’s port fortress strategy seems logical. He believes that by denying access to major ports, he can prevent the Allies from sustaining a Second Front. His aim is to starve the invasion of the supplies it needs for breakout and advance.

Yet by late 1943, Allied planners are already designing portable harbours. These prefabricated systems, known as Mulberries, will become the key to maintaining the offensive until a real port can be captured and brought into service.

| The Broader Context of Overlord |

In isolation, Hitler’s assumption appears sound. Without a port, the Allies risk failure. However, Operation Neptune is only the opening phase of a far larger, joint campaign. Once ashore, Allied forces are sustained by enormous quantities of materiel, stockpiled in Britain over many months. The initial landings are only the beginning of a sustained effort.

Although building up combat power in the lodgement area proves difficult, the Allies possess overwhelming naval and air superiority. The Anglo-American fleets protect the flanks and maintain supply lines. Allied air forces, in particular, play a vital role in disrupting German reinforcements. Through constant bombing of roads, railways, and airfields, they slow or even prevent the arrival of German formations at the front.

By 1944, Rommel recognises that warfare has fundamentally changed. Even experienced units from the Eastern Front face challenges unknown in Russia. General Fritz Bayerlein, commander of Panzer Lehr Division, later recalls Rommel’s warning. He quotes him as saying that the enemy is no longer a mass of fanatics but a technologically advanced and methodical force. The Allied approach is based on intelligence, precision, and unlimited resources. Rommel notes that determination alone no longer defines a soldier.

| Evolving Joint Allied Plans |

After considerable discussion, Churchill and Roosevelt agree to appoint General Dwight D. Eisenhower as Supreme Allied Commander. He receives formal notification on December 7th, 1943. Just five days later, Hitler appoints Field Marshal Rommel to command the Atlantic Wall’s defence. By Christmas Eve, Allied commanders gather in England as Rommel begins inspections along the French coast.

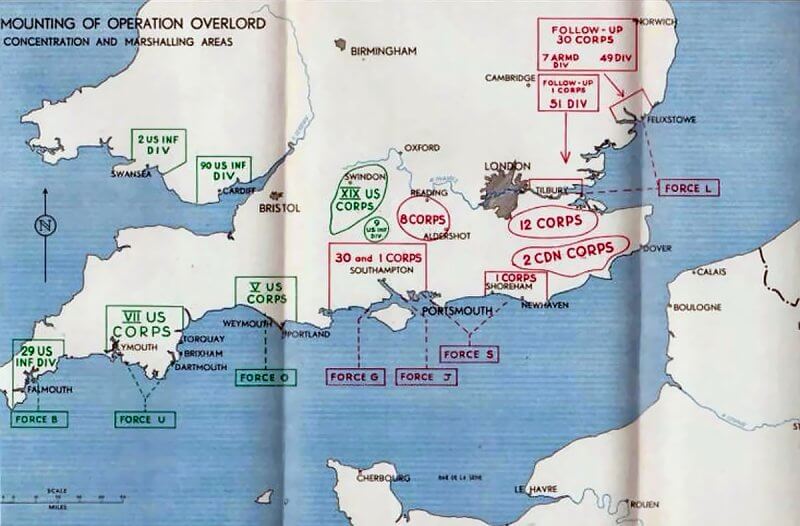

General Bernard Montgomery is appointed ground commander for the invasion. On reviewing the existing Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander plan, he identifies major flaws. General Morgan’s concept limits the initial assault to three divisions. This, Montgomery argues, is too narrow and too weak. He urges an increase in scale and scope.

Eisenhower agrees. The revised plan now calls for a five-division assault with four follow-up divisions. Montgomery argues that this wider front will confuse the German response, improve the lodgement’s security, and increase the likelihood of capturing key objectives, namely Cherbourg and Caen. These revisions are approved on January 21st, 1944. A new provisional date for D-Day is set: May 31st, 1944.

| Expanding the Invasion Front |

The Allies decide to extend the landing area. The western flank now includes the Cotentin Peninsula (Utah Beach), and the eastern flank extends to the River Orne (Sword Beach). Three airborne divisions are tasked with securing the flanks. Their mission is to block German movements and protect the main landings during their most vulnerable hours.

This expansion severely strains Allied resources. The Americans had planned to mount Operation Anvil, an invasion of southern France, at the same time as Overlord. Their intention was to divide German attention and draw reserves south. However, the Allies lack the necessary landing craft, aircraft, and warships for simultaneous operations on two fronts.

After heated debate, the decision is made to prioritise Overlord. The resources from the Mediterranean are reallocated. Operation Neptune, the assault phase of Overlord, becomes the main effort.

| The Final Assault Plan |

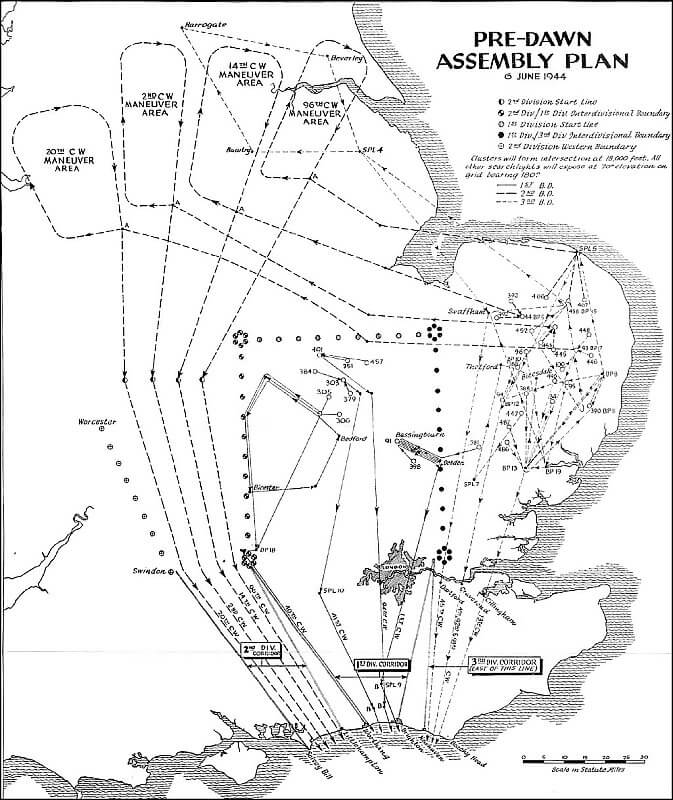

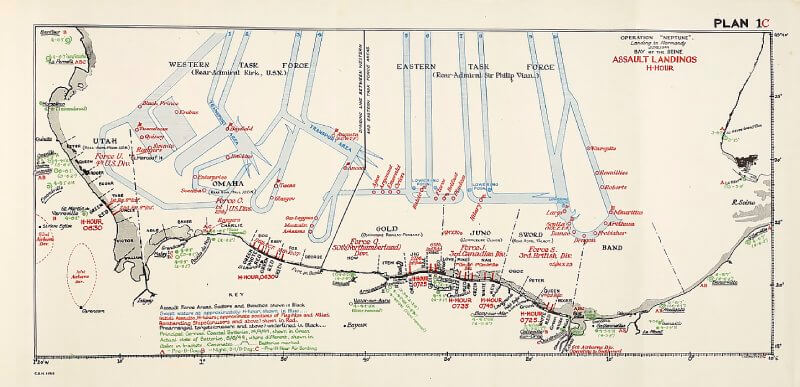

The final plan divides operations into two sectors. In the west, the United States First Army under General Omar Bradley will land on Utah and Omaha Beaches. Two American airborne divisions, will land inland on the western flank to disrupt German responses and support the amphibious assault.

In the east, the British Second Army under General Miles Dempsey will land on Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches. Each beach will be assaulted by an infantry division. On the eastern flank, the British 6th Airborne Division will drop by parachute and glider. Their objectives include the seizure of key bridges over the River Orne and its canal, and securing the high ground east of the river.

These operations aim to delay or block German reinforcements from attacking Sword and Juno Beaches. The Allied plan calls for all five beaches to be linked up by midnight on D-Day. Montgomery deliberately sets deep initial objectives. He seeks to avoid stagnation on the shoreline, as had occurred at Gallipoli in 1915 and Anzio in 1943.

| Selecting the Date and Time for D-Day |

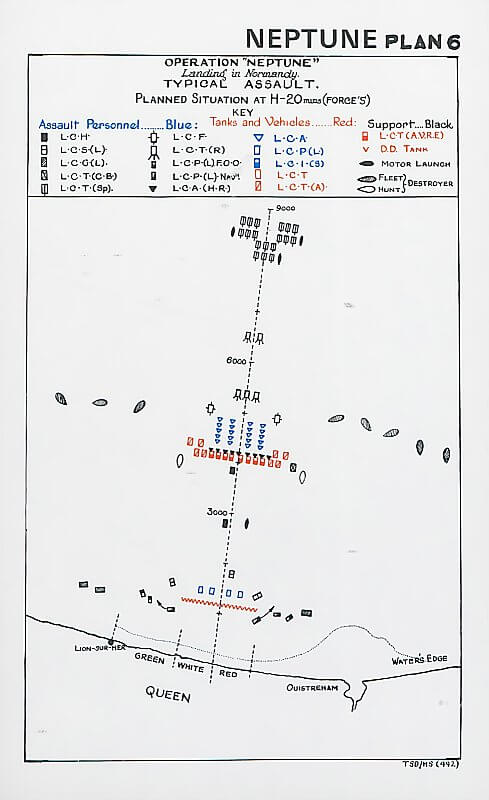

Determining the time and date for the assault proves a major command challenge. The ground forces prefer a night landing to achieve surprise. Naval and air commanders favour daylight. They need visibility to strike enemy defences with accuracy and to coordinate the vast number of landing craft.

Rommel’s deployment of obstacles on the beaches alters the equation. On 1 May 1944, Admiral Bertram Ramsay and Eisenhower agree to a compromise. The landing must begin three to four hours before high tide and ten minutes after sunrise. This schedule allows engineers to clear beach obstacles before the rising tide hides them.

The airborne operations must also occur during moonlight for accurate drops. These conditions only occur on three days each lunar month. Weather becomes the final, and most unpredictable,factor. Accurate forecasts beyond a few days are impossible. As a result, the final go-ahead for D-Day must be taken within days of the invasion window.

If poor weather delays the operation beyond the available days in early June, the entire invasion must be postponed for several weeks. The tension among commanders increases as the critical period approaches.

| The Joint Campaign: Allied Air Power |

By early 1944, the Allies have developed a highly effective joint force capability. This integration allows land, sea, and air forces to operate together in a coordinated and mutually reinforcing manner. Within this joint structure, they also achieve success in a combined setting, coordinating the efforts of multiple national forces under a single strategic command.

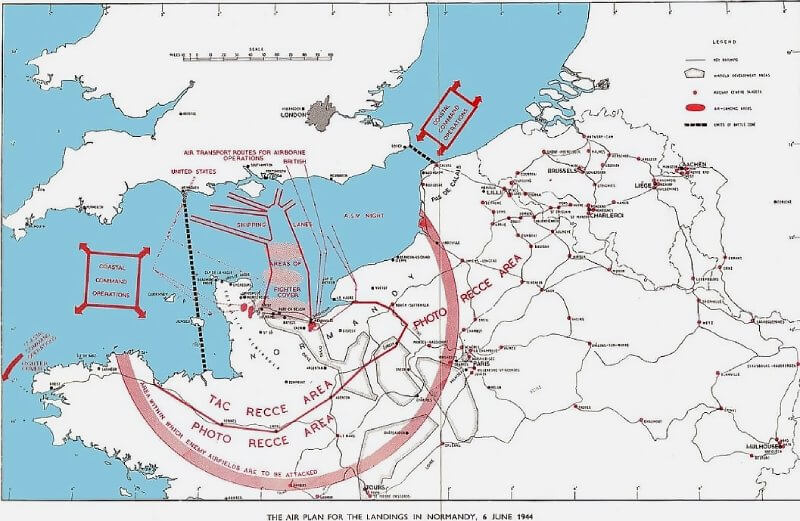

On April 14th, 1944, General Eisenhower assumes overall control of Allied strategic forces. He quickly instructs his British deputy, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, to harmonise the interests of Allied air commands. Tedder’s role is to shape a unified air campaign in direct support of the forthcoming invasion.

Tedder works closely with Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, commander of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force. Together, they oversee the development and execution of a devastating and comprehensive air plan. Leigh-Mallory stresses the importance of tightly coordinated air operations in support of land forces. He therefore establishes a small operational organisation, the Advanced Allied Expeditionary Air Force (AEAF), to plan and direct the tactical air assets of the Second Tactical Air Force and Ninth Air Force.

Despite friction and disagreement among commanders, Tedder and Leigh-Mallory succeed in concentrating the efforts of British and American air forces. Their coordination proves crucial to the success of both Operation Neptune and the wider Overlord campaign. The objective is clear: gain air superiority, disrupt German movements, and provide close air support to land and naval forces.

The Allied air campaign supporting Overlord is structured into four phases:

- Phase One involves the interdiction of German air and naval forces operating in the Channel. Allied aircraft also conduct intensive reconnaissance missions during this phase.

- Phase Two, beginning in March 1944, marks the preparatory stage. Heavy bombers begin striking fortresses, naval bases, and key infrastructure, including bridges, roads, railways, and radar installations. Importantly, to preserve operational deception, two-thirds of all bombing raids occur outside Normandy.

- Phases Three and Four coincide with the invasion itself and the subsequent battle in Normandy. The scale of the commitment is immense. Fifty-four fighter squadrons cover the beaches, fifteen protect the fleet, and thirty-three escort bombers and airborne forces. Thirty-six bomber squadrons support ground forces directly. An additional seven squadrons of Spitfires and Mustangs handle fire control. In total, more than 5,000 Allied fighters operate over the invasion area.

| The Strategic Impact of Allied Air Power |

The effect of this campaign is profound. From January 1944 to D-Day, the Transportation Plan targets the French railway system. Bombing attacks devastate the network. By June, German rail traffic in France is reduced to 30 percent of 1943 levels. Bridges across the Seine and Loire rivers are destroyed. Major routes into Normandy are rendered impassable. These disruptions delay the deployment of German reserves, including panzer and Panzergrenadier divisions.

To support deception efforts, bombing continues across northern France and Belgium. This widespread activity confuses German intelligence. The enemy cannot determine where the invasion will take place. The two-to-one ratio of raids outside Normandy reinforces this uncertainty.

Despite this success, the path to a unified air campaign is not without resistance. Lieutenant General Carl Spaatz and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, the so-called ‘Bomber Barons,’ initially oppose the diversion of strategic air assets. They argue that heavy bombers must focus on targets within Germany.

Tedder disagrees. He insists that strategic bombers must support Overlord. After prolonged political and military debate, his view prevails. The resulting air plan blends strategic bombing and tactical air power into a cohesive and deadly force.

Part of Tedder’s strategy is to provoke the Luftwaffe into battle. His goal is to destroy the German fighter force before D-Day. From January to June 1944, this policy succeeds. In that period, 2,262 German fighter pilots are killed. On average, the Luftwaffe fields 2,283 fighter pilots at any one time. In May alone, one-quarter of the German fighter pilot force is lost.

From April 1944 onwards, Allied aircraft attack every airfield within 210 kilometres of the invasion beaches. As a result, the Luftwaffe is forced to withdraw what remains of its air power. These aircraft are dispersed far inland, particularly around Paris. By D-Day, German air presence over Normandy is minimal. Only two German fighters attack the beaches in daylight.

| Multimedia |

| The Joint Campaign: Naval Forces |

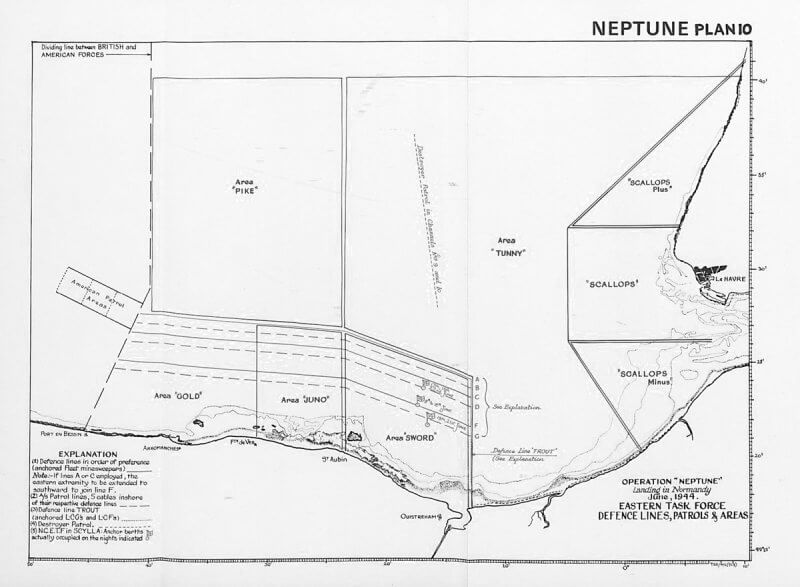

The maritime element of Operation Overlord, code-named Neptune, falls under the command of Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay. His responsibility is immense: planning, preparing, and executing the largest amphibious operation in history. Some 4,100 vessels of every type are committed to the initial assault. Each is assigned a precise role in Ramsay’s vast choreography. His objective is clear: to secure a lodgement on the continent from which further offensive operations can be developed.

Ramsay must also sustain the land forces in Normandy after the landings. Naval gunfire becomes a key feature of this support. Heavy guns engage coastal defences before H-Hour and continue to support operations until the front moves beyond range. During the Battle of Normandy, naval fire missions prove decisive,both defensively and offensively. The fleet also plays a central part in deception operations, particularly those supporting Fortitude, which aims to divert German forces toward the Pas-de-Calais.

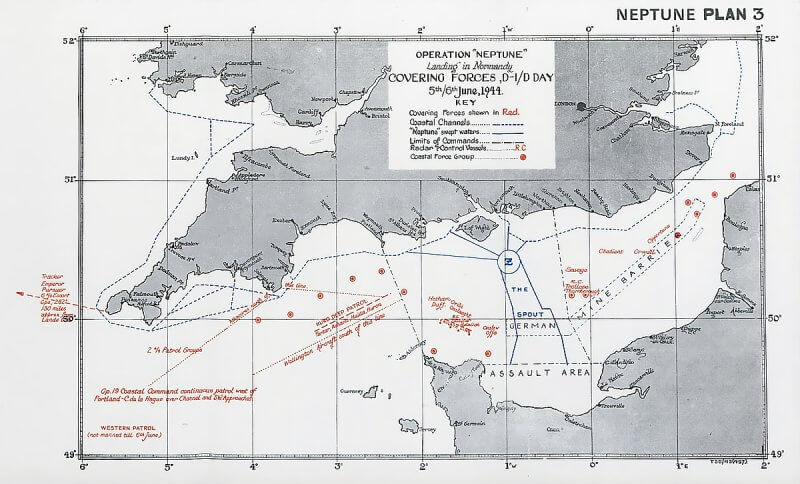

Preparations for the naval assault begin long before dawn on June 6th, 1944. A combined force of 278 American and British minesweepers begins clearing the approaches through the English Channel in the days leading up to the invasion. Ten primary assault corridors are swept and marked, five to the western beaches, allowing the larger warships to approach their bombardment positions and enabling the initial waves of landing craft to move in under protection.

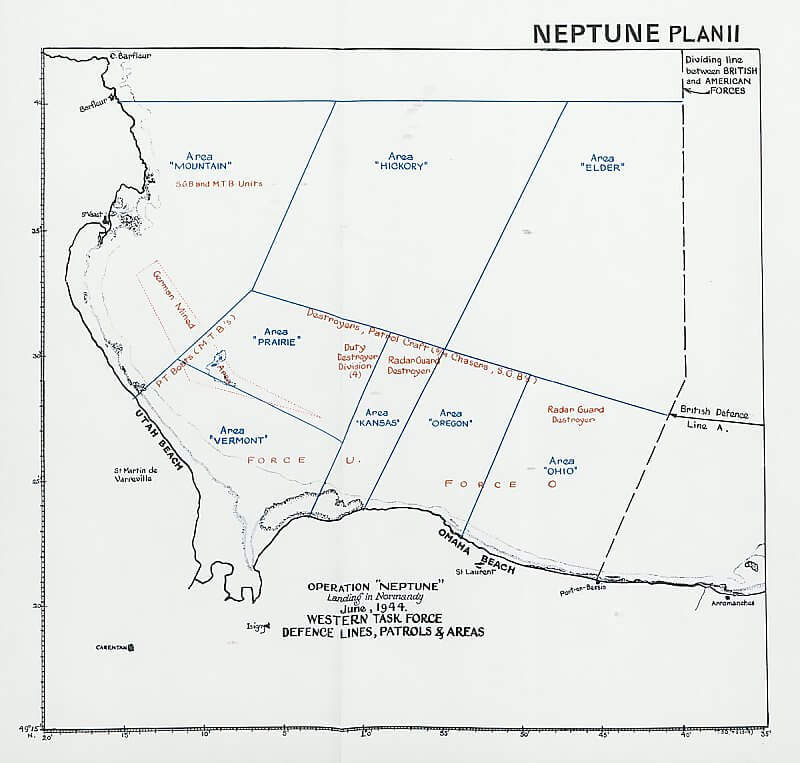

Responsibility for supporting landings at Omaha and Utah Beaches falls to the Western Naval Task Force, commanded by Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk of the United States Navy. His flagship is the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Augusta, from which he directs naval operations in coordination with Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, commanding the U.S. First Army. The Western Naval Task Force includes more than 200 warships and landing craft, divided into beach-specific groups under subordinate flag officers.

Force “O”, under Rear Admiral John L. Hall, is assigned to Omaha Beach and supports the landings of V Corps. Force “U”, commanded by Rear Admiral Don P. Moon, is responsible for Utah Beach and the landing of VII Corps. General Bradley embarks aboard U.S.S. Augusta, while Major General Leonard T. Gerow, commanding V Corps, is embarked on the amphibious command ship U.S.S. Ancon, a specially modified vessel equipped for real-time battlefield coordination. Its role in the operation remains classified in 1944.

Kirk’s task force also bears responsibility for protecting the seaborne flanks from German naval interference. The Kriegsmarine’s Schnellboots, or E-Boats, based at Cherbourg and Le Havre, remain a significant threat. Their speed and armament make them effective raiders, particularly under cover of darkness. This danger is tragically demonstrated on the night of 28 April 1944, during Exercise Tiger, a full-scale rehearsal for the Utah Beach landing. A flotilla of German E-Boats intercepts Convoy T-4 in Lyme Bay, sinking three U.S. Landing Ship Tanks in under half an hour. The surprise attack results in the loss of 749 American personnel, including most of the 3206th Quartermaster Company. Only nine are rescued alive.

The fleet must also guard against enemy naval attacks. The Kriegsmarine’s Schnellboots, or E-Boats, pose a serious threat. Stationed at Cherbourg and Le Havre, these fast torpedo boats have already proved deadly. On April 28th, 1944, during Exercise Tiger, a rehearsal for D-Day, German E-Boats attack Convoy T4 in Lyme Bay. The convoy, transporting troops of the US 4th Infantry Division, is ambushed in darkness. Three Landing Craft Tank are sunk within twenty-five minutes. In total, 749 American troops perish, including most of the 3206th Quartermaster Company. Only nine survivors are rescued the following morning.

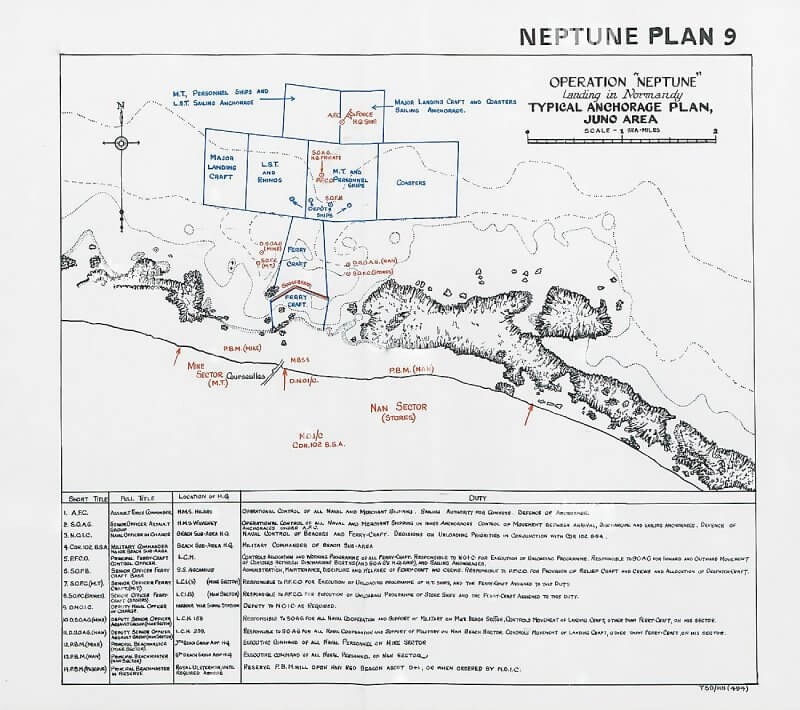

Responsibility for supporting the landings at Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches lies with the Eastern Naval Task Force, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Philip Vian of the Royal Navy. His flagship is the headquarters ship H.M.S. Scylla, from which he oversees naval operations in concert with Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey, commanding the British Second Army. The Eastern Naval Task Force comprises over 400 warships and landing craft, organised into national and beach-specific groups.

Force “G”, under Commodore Douglas Pennant, is assigned to support British XXX Corps at Gold Beach. Force “J”, commanded by Commodore E.C. Thornton, is tasked with landing the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division at Juno Beach. Force “S”, under Commodore Oliver H. Collard, is responsible for putting ashore British I Corps at Sword Beach. Dempsey himself embarks aboard H.M.S. Bulolo, another specially converted amphibious headquarters ship, coordinating the eastern assault from just offshore.

Naval preparations begin well in advance of H-Hour. Minesweepers from the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy, operating alongside Allied vessels, clear the approach routes through the German defensive minefields. In total, five primary channels are swept towards the eastern beaches, ensuring safe passage for the bombardment squadrons and assault waves. This work is perilous, carried out under the threat of coastal batteries and patrols.

Vian’s fleet is also tasked with defending against surface threats from German naval forces. Schnellboots, or E-Boats, based at Le Havre and Cherbourg remain a known menace. On the night before the landings, a small E-Boat formation attempts to intercept Allied vessels off the eastern flank. The destroyer H.No.M.S. Svenner, part of the Sword Beach screen, is struck by a torpedo and sinks with heavy loss of life. It is the only major Allied warship lost to enemy naval action during the invasion.

Despite this, the German Kriegsmarine fails to disrupt the landings. Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz’s directives for aggressive torpedo attacks are poorly executed due to limited fuel, harbours under bombardment, and overwhelming Allied naval supremacy.

| Multimedia |

| Sustaining the Invasion: Naval Logistics and Control |

Beyond firepower, the navy ensures the continued flow of supplies. Ramsay creates a network of control headquarters to manage beach landings, ship turnarounds, and repairs. The Combined Operations Tug Organisation and the Combined Operations Repair Organisation are activated to maintain fleet mobility and effectiveness.

One of the most ambitious tasks involves the Mulberry harbours. These artificial ports are floated across the Channel and assembled off Omaha and Arromanches. The effort requires 10,000 men and 160 tugs. By D+4, both Mulberries have to be in place. They enable large volumes of cargo to reach shore without reliance on existing ports.

Fuel delivery is another major task. Before the capture of Cherbourg, fuel is offloaded via flexible steel pipes offshore near Port-en-Bessin.

| Multimedia |

| Sources |