| Podcast |

| Development History |

The concept of amphibious tanks exists before the war, yet early designs struggle with buoyancy. Heavy armour proves difficult to float. Designers test detachable pontoons and rigid floats, as seen in Japanese work, but these systems are bulky and slow. They cannot support large armoured formations in assault conditions. The breakthrough comes in 1940. Nicholas Straussler, a Hungarian-born engineer, creates a collapsible flotation screen made from waterproof canvas. The screen folds around the hull in transit. When raised, it forms a light and flexible boat-shaped wall. The screen increases buoyancy and allows the tank to float, yet it can be folded down for land combat.

In July 1940, Straussler receives a redundant Light Tank Mk VII Tetrarch from the British 1st Armoured Division. The vehicle weighs about eight tonnes. The choice of the Tetrarch is deliberate. It is the lightest available tank and ideal for a risky concept. The Royal Navy’s Construction Branch initially dismisses the idea as impractical. Straussler continues regardless and develops the system further.

By June 1941, he has fitted the Tetrarch with a collapsible flotation screen and an engine-driven propeller. The first trial takes place on the Brent Reservoir, also known as the Welsh Harp, in north London. General Sir Alan Brooke, Commander-in-Chief Home Forces, attends the demonstration and becomes an early supporter. The small tank successfully swims across the reservoir. The trial takes place on the same water where a floating Mark IX tank is tested at the end of the First World War.

Encouraged by the freshwater results, Straussler moves to sea trials. In December 1941, tests take place off Portsmouth, near Hayling Island, possibly within Langstone Harbour. The Tetrarch floats and manoeuvres in choppy coastal water and proves the soundness of the system. As a result, the British Tank Board approves the adaptation of the Duplex Drive equipment to a more suitable combat vehicle, the Vickers-Armstrong Valentine infantry tank. From this point, the Tetrarch DD serves mainly as a proof-of-concept machine.

Further experiments follow with the prototype. These include firing trials to test whether the main armament can operate while the tank is afloat. The United States Army also shows interest. American engineers attempt to fit the Duplex Drive system to an M3 Stuart light tank. That early American trial ends in failure when the prototype sinks quickly. The incident confirms the British preference for larger, more stable tanks as production Duplex Drive platforms.

In September, the Tank Board decides that Straussler should apply the Duplex Drive system to a Vickers-Armstrong Valentine infantry tank. A Valentine II, powered by an AEC A190 diesel engine, is issued for the work. The heavier tank requires a larger rubberised canvas screen, so the design is adjusted. The propeller also needs a new arrangement, and a drive shaft is extended from the rear of the transmission. A pivoting mechanism allows the crew to lift or lower the propeller as required.

Trials of the Valentine DD begin in May 1942. In July, the Ministry of Supply approves the construction of 450 Valentine DD tanks. These are all based on the Valentine V, which uses the American GMC 6.71S diesel engine rather than the earlier AEC unit. At the same time, the Royal Armoured Corps reports that sea-going trials have begun, yet the General Staff issues a policy paper stating that amphibious tanks are not required. Straussler refines the DD system through 1942 and 1943 as trials continue with the Valentine DD.

In late 1942 the British Army creates the 79th Armoured Division under Major-General Percy Hobart. The division develops specialised armour for future invasions. The disaster at Dieppe in August 1942 reinforces this need. Tanks landed from craft at Dieppe struggle on the beach. Many arrive late or fail to move inland. Amphibious tanks able to land under their own power become essential.

Despite this contradiction, Metropolitan-Cammell in Birmingham prepares to manufacture the Valentine DD using the hulls they are already building. Production begins in March 1943 with a planned output of thirty-five vehicles per month. By mid-1943, however, the Royal Armoured Corps is already asking for a DD version of the new American Sherman tank.

During this period, the Army selects the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards, the 13th/18th Royal Hussars, and the East Riding Yeomanry as the first regiments to train on the new equipment. They move to Fritton in East Anglia, which soon becomes the main training centre for British, American, and Canadian DD crews.

Fritton Lake provides more than open water. A separate submerged escape tank is installed for emergency drills. Crews climb into an armoured hull placed at the bottom of this tank. Water is then allowed to rise and submerge the vehicle. When ordered, the men activate their Amphibious Tank Escape Apparatus and climb out through a hatch before surfacing. After mastering these drills, the crews move on to open-water training. Additional training centres are created at Loch Fyne and the Moray Firth in Scotland, at Barafundle Bay in South Wales, at Stokes Bay near Gosport, and at Studland Bay on the Dorset coast.

By mid-1943, the Valentine itself is approaching obsolescence. The Valentine IX carries the 57-millimetre 6-pounder gun. The Valentine XI mounts a 75-millimetre gun derived from the 6-pounder to take American ammunition. By late 1943 Metropolitan-Cammell has converted 625 Valentines. These include Mk V, Mk IX, and Mk XI models. The Mk IX and Mk XI carry 6-pounder or 75mm guns. Yet shortcomings appear. The Valentine offers limited freeboard and must swim with the gun facing rearwards.

Yet the design cannot keep pace with the war. The hulls continue in production for a time and form the basis of the Archer, which mounts the powerful 17-pounder anti-tank gun on a Valentine chassis.

As D-Day approaches, it becomes clear that the Sherman DD is more seaworthy than the Valentine. The Sherman has more internal space and can swim with its gun facing forwards. The Valentine must swim with its turret reversed and must remove the screen before it can fire. Even as Sherman DD’s arrive in Britain, crews continue to train on the Valentine.

On April 4th, 1944, Exercise Smash 1 is held at Studland Bay. It is the first of a series of live-fire rehearsals planned for April. The 4th/7th Dragoon Guards has already demonstrated Valentine loading and launching drills in December 1943. That earlier exercise ends with only two technical issues and produces a memo stating that the DD tank is a formidable new weapon.

The exercise has already been delayed due to rough weather. The beach is divided into King Green and King White. Two squadrons of Valentine IX and XI DDs launch from LCT(3)s to support infantry of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division. The wind rises and the sea becomes heavy with waves slopping into the tanks as they leave the craft. The extra water disturbs the trim. The bow dips. Water pours over the canvas screen and the tank sinks. The Valentine’s bilge pumps of some tanks cannot cope. Although most of the Valentines reach the beach with many drivers sitting waist-deep in water when they finally touch the sand, seven tanks are lost. Six crewmen drown despite the escape training at Fritton. The dead are Lieutenant C. Gould, Sergeant V. Hartley, Corporal A. Park, Corporal V. Townson, Trooper A. Kirby, and Trooper E. Petty.

Two weeks later, on April 18th, 1944, King George VI watches Exercise Smash 3 from the Fort Henry bunker. He stands with Prime Minister Winston Churchill, General Eisenhower, and General Montgomery. On that day, a regiment of Valentine DDs is launched and lands without loss.

By that time it is clear that the M4 Sherman is a better platform. It offers greater buoyancy and can keep its 75-millimetre gun facing forward while swimming. By April 1943 Straussler’s flotation screen adapts successfully to the Sherman. The first Sherman DD prototypes are ready soon after.

Production increases during 1944. Great Britain converts 693 Sherman DD tanks that year. An additional 247 Valentine DD’s enter service mainly as training vehicles. The United States adopts the Sherman system after a successful demonstration in November 1943. American officers take Straussler’s plans and begin local production. By early 1944, U.S. factories produce DD Shermans at a rate of fifteen per day for Allied forces.

By the time of the Normandy invasion, British, Canadian, and American forces have trained extensively with DD tanks. Valentine DDs serve mainly as training vehicles. Crews learn the system on these older tanks before moving to Sherman DD’s. By mid-1944 the Valentine DD is obsolete in Europe. Many are scrapped or shipped to training units in Burma and India. Valentine DDs see combat only once, and only in a supporting role. Their single operational use takes place in northern Italy in 1945. During the final Allied advance, a small number of Valentine DD’s assist the 7th Queen’s Own Hussars. They are not employed as swimming tanks. Instead, they serve as improvised fuel carriers during the Adige River crossing. Their flotation screens allow them to shuttle fuel across the water to supply Sherman DDs already fighting on the far bank. This brief episode becomes the only recorded combat service of the Valentine DD.

| Multimedia |

| Amphibious Technique: Flotation and Propulsion Systems |

The Duplex Drive technique allows a tank to swim without giving it a permanent buoyant hull. It uses temporary buoyancy and powered movement in water. Two main elements make the system work.

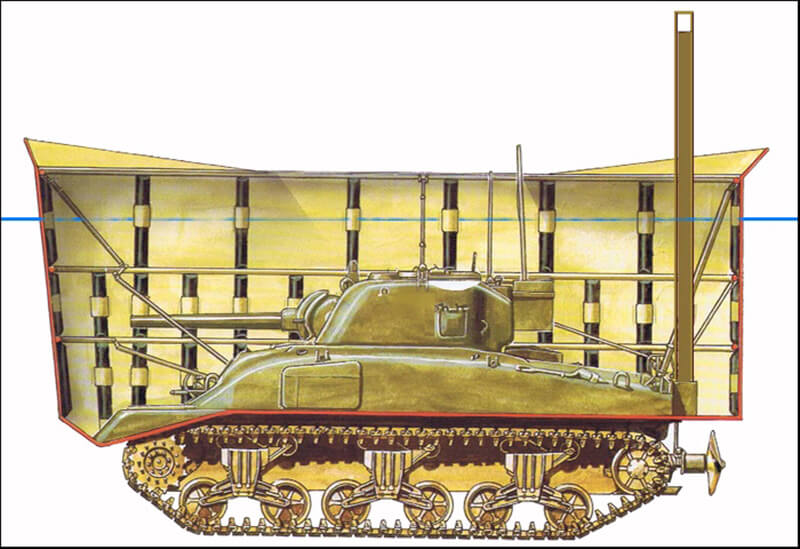

The flotation screen is a collapsible canvas structure fitted around the upper hull. When stowed, the canvas folds flat around the tank and allows normal visibility and movement. To deploy, crews inflate rubber tubes using compressed air. Metal struts rise with the tubes and pull the canvas skirt into a rigid upright position. Straussler explains that each tube produces about 270 kilograms of upward force when filled. Dozens of tubes therefore hold the screen upright with nearly twelve tonnes of total force. The canvas and frame form a hollow raft around the tank. This increases displacement and keeps the heavy vehicle afloat. The canvas wall sits just above the turret when raised. On the Sherman DD, the top of the skirt usually sits only about thirty centimetres above the waterline. This gives very little freeboard. The tank can only operate safely in calm water. Sea State Three or Four is considered the practical limit. Waves of one or two metres can swamp the canvas. The canvas is tough but remains vulnerable to puncture from obstacles or gunfire. DD crews rely on smoke, low visibility, and surprise to cross the water safely. To collapse the screen, the crew releases the air through valves. They usually wait until the tank enters shallow water where the tracks can bite, or they deflate it immediately if enemy fire threatens the canvas.

The propulsion system gives the tank movement in water. Once afloat, the tank needs power and steering. Straussler adds propellers driven by the tank’s own engine, a dual system that gives the name Duplex Drive. Sherman DD tanks carry two propellers at the rear, one on each side. Smaller tanks like the Valentine normally use a single screw. Power transmission is achieved without breaching the hull armour. Straussler attaches a crown gear to the rear idler or sprocket. A pinion gear then connects this to the propeller shaft. When the driver engages the water gear, the turning tracks spin the crown gear and drive the propellers. The propellers sit on hinged arms lifted clear of the ground on land. In water, the propellers swivel for steering. The driver uses hydraulic controls to angle them. The commander stands behind the turret and uses a tiller bar for fine corrections. Water speed is slow. Most DD tanks reach only three or four knots, about five to seven kilometres per hour. This low speed means launches usually take place close to shore to reduce exposure. As the tank enters water of about 1.5 metres or less, the tracks begin to grip the bottom. The crew then collapses the screen, raises the propellers, and shifts to normal drive to climb onto the beach.

The entire transition is risky. Tanks can flood in rough water or drift off course in current and wind. They ride high in the water and are very vulnerable to waves and surf. Underwater obstacles and sandbars can trap them. Training stresses precise launch technique, including careful backing out of a landing craft at the correct speed to avoid swamping. Crews also learn to balance weight inside the tank. Yet despite training, accidents occur. Flooding and sinking happen often enough to show how narrow the safety margin is.

In essence, the Duplex Drive system turns a tank into a temporary boat for a brief period. It is an ingenious compromise. It uses a removable flotation collar rather than modifying the armour or hull shape. Crucially, the system allows DD tanks to launch from standard landing craft at sea and swim under their own power towards the shore. This capability offers the assault troops immediate armoured support emerging from the surf. Such support can unsettle defenders who expect no tanks until landing craft reach the beach. The system works well in favourable weather with careful preparation. It fails quickly in poor conditions.

| Multimedia |

| Technical Characteristics of DD Tank Variants |

Duplex Drive tanks retain the core features of their base models. They keep the original armour, armament, and engine, but gain specialised amphibious equipment. With the Tetrarch DD being a prototype the two main wartime variants are the Valentine DD and the Sherman DD.

| Tetrarch DD Tank |

The Tetrarch DD is based on the standard Light Tank Mk VII. It remains a light airborne tank designed by Vickers-Armstrong. It weighs about 7.6 tonnes, around 16,800 pounds. It measures roughly 4.11 metres in length, 2.31 metres in width, and 2.12 metres in height. The crew consists of three men: commander, gunner, and driver. The armour uses riveted plate up to fourteen millimetres thick. Protection is modest by mid-war standards.

The main armament is the QF 2-pounder gun of forty millimetres, with about fifty rounds carried. A coaxial 7.92-millimetre Besa machine gun sits beside the main gun. The tank uses a twelve-cylinder Meadows petrol engine producing about 165 horsepower. Power-to-weight is roughly twenty-two horsepower per tonne. On land, the Tetrarch reaches about sixty-four kilometres per hour, roughly forty miles per hour. Its small size and light armour make it quick but vulnerable as the war progresses.

Straussler’s Duplex Drive conversion adds a collapsible waterproof canvas skirt around the upper hull. This screen provides the extra buoyancy needed for swimming. When raised, it forms a canvas boat that encloses the tank above the tracks. The base of the screen attaches to a rigid metal frame fixed around mudguard level on the hull.

The skirt is supported by inflatable rubber tubes and metal struts. Around thirty-six vertical tubes run around the perimeter and are linked by horizontal steel hoops. Together they give the screen its shape and stiffness. In effect, the system creates a temporary hull with enough displacement to float about eight tonnes.

When not required, the canvas screen folds neatly down around the hull. Erecting it takes only a few minutes. Compressed air inflates the rubberised tubes and forces the skirt to spring upright and lock into position. Once ashore, the crew can collapse the screen quickly. Later versions use release cables or small explosive cords to deflate the tubes instantly and drop the skirt for combat.

In water, the Tetrarch DD moves using a propeller powered by its own engine. Straussler’s Duplex Drive mechanism allows the crew to switch engine power between the tracks and the propeller through a transfer gearbox.

The first prototype does not yet use this full system. For the earliest swim trial, the Tetrarch carries an outboard motor. That trial is therefore not a true Duplex Drive test. The design soon evolves into a fully integrated arrangement.

In the production Duplex Drive layout, power runs from the rear drive sprocket to the propeller. A crown gear is added to the sprocket and meshes with a pinion on the propeller shaft. When the crew engages the transfer box, drive to the tracks is disconnected. The engine then turns the propeller instead of the tracks.

The Tetrarch DD uses a single three-bladed propeller mounted at the rear. Later DD tanks, such as the Sherman, adopt twin propellers for greater thrust and reliability. Steering on water is achieved by pivoting the propeller assembly. The propeller can swivel from side to side to direct thrust. It can also be raised out of the way when not used.

Both driver and commander share responsibility for steering. On later DD types, a hydraulic linkage allows the driver to turn the prop. The commander can assist from a small tiller at the rear of the turret. The modest engine drives the Tetrarch through the water at only a few knots, about four kilometres per hour. This is sufficient for harbours, rivers, and short coastal crossings.

For swimming, the tank remains fully sealed. All hull openings are closed, and a bilge pump removes any leakage. The Duplex Drive system therefore allows the Tetrarch to sail under its own power, then revert to tracked movement as soon as it reaches land.

Development of the Tetrarch DD exposes many inherent problems with amphibious tanks. Buoyancy and stability remain constant concerns. The canvas screen offers only limited freeboard, just a few feet above the water. Any tear or flooding can swamp the tank very quickly.

The Duplex Drive system on the Tetrarch introduces a clever blend of flotation and propulsion to create a swimming tank. The design uses a collapsible flotation screen and a dual-mode drive system. Together they allow the light tank to move through water and then continue fighting on land.

The collapsible flotation screen becomes the Tetrarch’s most distinctive feature. It is essentially a folding canvas boat fitted around the upper hull. When raised, it encloses the top half of the tank and traps enough air to keep the vehicle afloat. The base of the skirt attaches to a metal frame fixed around the mudguard line. The sides are made from thick rubberised canvas. Vertical inflatable tubes sit between the layers of canvas and are filled from compressed-air cylinders. These tubes stiffen the screen and hold it upright. Steel hoops add further structure. The Tetrarch uses around thirty-six inflatable tubes, forming a continuous ring of buoyancy around the vehicle.

To deploy the screen, the crew halts at the water’s edge and inflates the tubes. Within minutes, the canvas rises to chest height around the turret. Once erected, the tank sits inside what looks like a canvas raft. The system gives surprising buoyancy for such a small vehicle. After completing the swim, the crew drops the screen rapidly using quick-release valves or explosive cords. The canvas then collapses or folds down, allowing the tank to fight on land without obstruction.

The propulsion system provides the second half of the Duplex Drive concept. Duplex Drive refers to the tank’s two methods of movement: conventional tracks on land and a propeller in water. For aquatic travel, Straussler introduces a transfer gearbox that switches power from the tracks to a marine propeller. The earliest prototype uses a simple outboard motor, but this soon gives way to a fully integrated design.

In the refined arrangement, the system uses the tank’s own rear sprocket. A special gear is fitted to the sprocket and drives a pinion connected to a propeller shaft. When the crew engages the transfer box, the engine stops driving the tracks and spins the propeller instead. The Tetrarch carries a single three-bladed propeller at the centre rear of the hull. Later DD tanks, including the Sherman, use twin propellers for extra thrust and security.

While swimming, the driver controls the throttle to move the tank forward. Steering is achieved by swivelling the propeller on a vertical axis to direct thrust. A simple tiller or mechanical linkage permits left or right movement. The tracks can also be turned slowly to act as rudders when required. The Tetrarch’s water speed reaches about three to four knots, roughly five to seven kilometres per hour. This is enough for harbour crossings or short coastal runs. Once the hull touches the beach, the crew switches back to tracked drive, raises the propeller, and collapses the flotation screen. The tank returns to full combat readiness within minutes.

The Duplex Drive system offers clear advantages. It gives amphibious capability without major changes to the tank’s core structure. The Tetrarch can still drive and fight like any normal light tank once the screen is down. However, the system has serious limitations. The canvas skirt remains fragile. Surf, rocks, or enemy fire can tear it. The inflatable tubes are especially vulnerable, and even light damage can collapse the screen. Early trials show this clearly when a test tank sinks after its skirt is riddled with bullet holes.

The Tetrarch’s small size also limits performance. Only a few feet of canvas stand above the waterline, leaving very little freeboard. Any strong wave threatens to swamp the tank. The system is suitable only for sheltered water or moderate sea states. Later designs address these issues with higher freeboards, stronger materials, and more rigorous crew training.

Despite these limitations, the Tetrarch DD proves the core idea. It shows that a standard turreted tank can float, steer, and propel itself across open water using temporary flotation gear. Before Straussler’s trials, such a notion appears almost impossible.

| Multimedia |

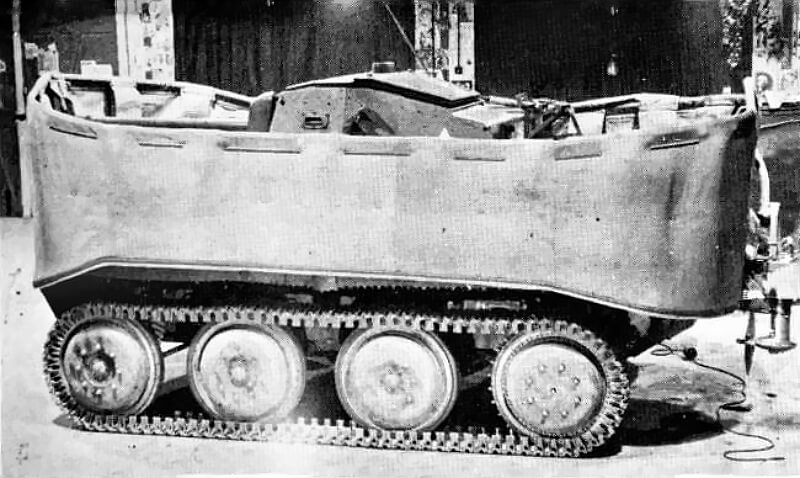

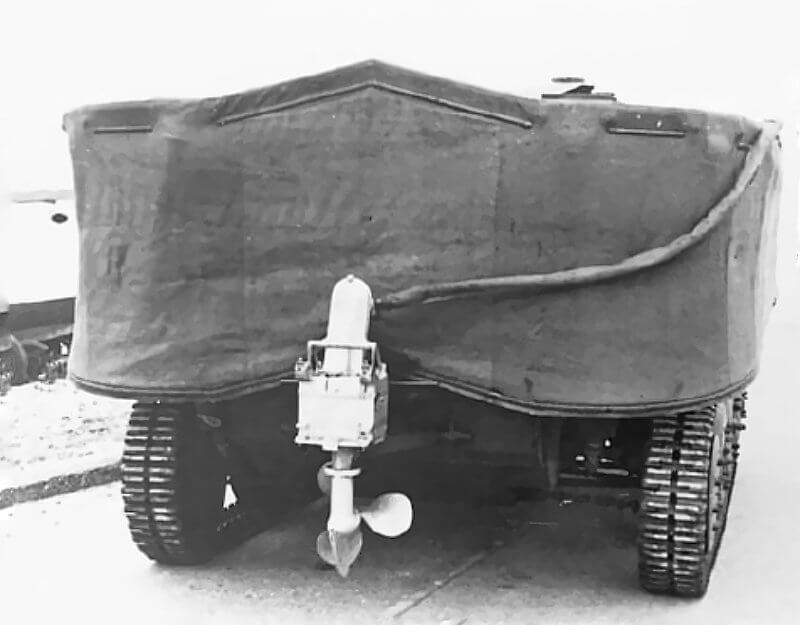

| Valentine DD Tank |

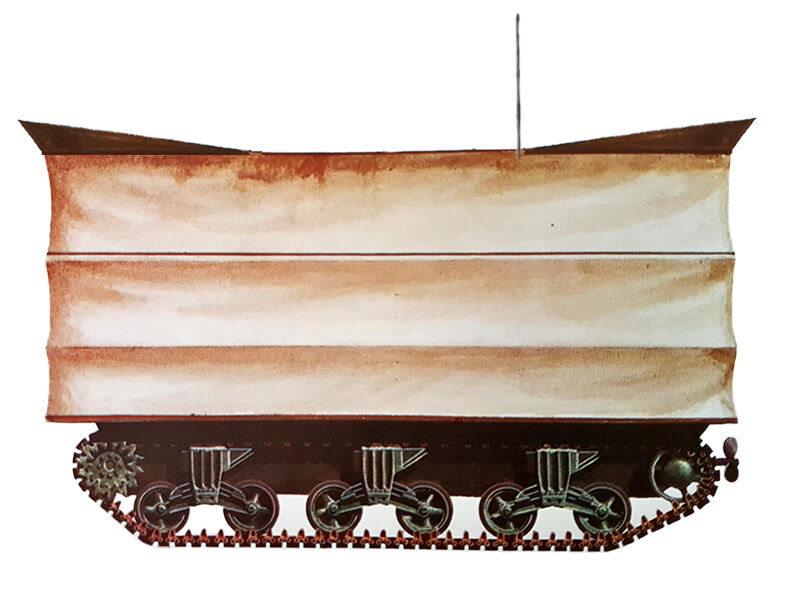

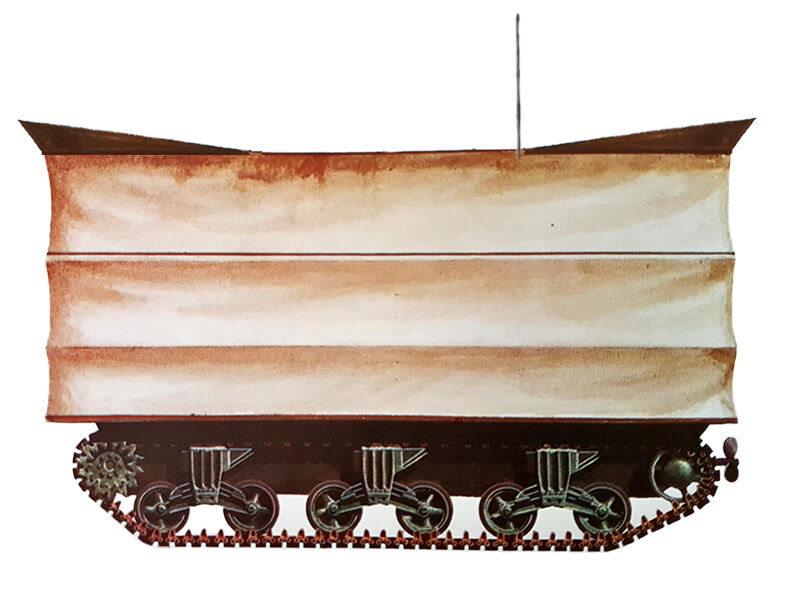

The Valentine DD is a British-built infantry tank adapted for amphibious use. It weighs between sixteen and seventeen tonnes in combat trim. It measures about 5.4 metres in length, 2.6 metres in width, and 2.2 metres in height with the screen folded. It remains small and has a low silhouette. The armour reaches about sixty-five millimetres on the turret front in the later marks. This protection makes the tank well shielded for its size.

Early conversions carry the QF 2-pounder gun of forty millimetres. Most later conversions use the Mk IX or Mk XI with a 6-pounder gun of fifty-seven millimetres or a 75-millimetre gun. A coaxial machine gun remains standard. The crew consists of three or four men, including the driver, the commander, the gunner, and sometimes a loader in the three-man turret.

The tank usually uses a GMC diesel of 138 horsepower or an AEC diesel, depending on the model. It reaches a land speed of about twenty-four to twenty-six kilometres per hour. In water it moves much more slowly and reaches only a few knots. Its small size limits seaworthiness in anything rougher than modest conditions.

The DD equipment includes a canvas flotation screen fitted around the upper hull. Inflatable rubber tubes and a light framework support the screen when it rises. The raised screen gives a freeboard of about one metre above the water. A propulsion system sits at the rear. Most Valentine DD’s use a single screw propeller driven by the engine and transmission. Sherman DD’s later use twin propellers, but the Valentine’s smaller hull usually carries only one. The crew can lift or disengage the propeller once ashore. The Duplex Drive name reflects the dual modes of propulsion, with tracks on land and a propeller in water.

| Multimedia |

| Sherman DD Tank |

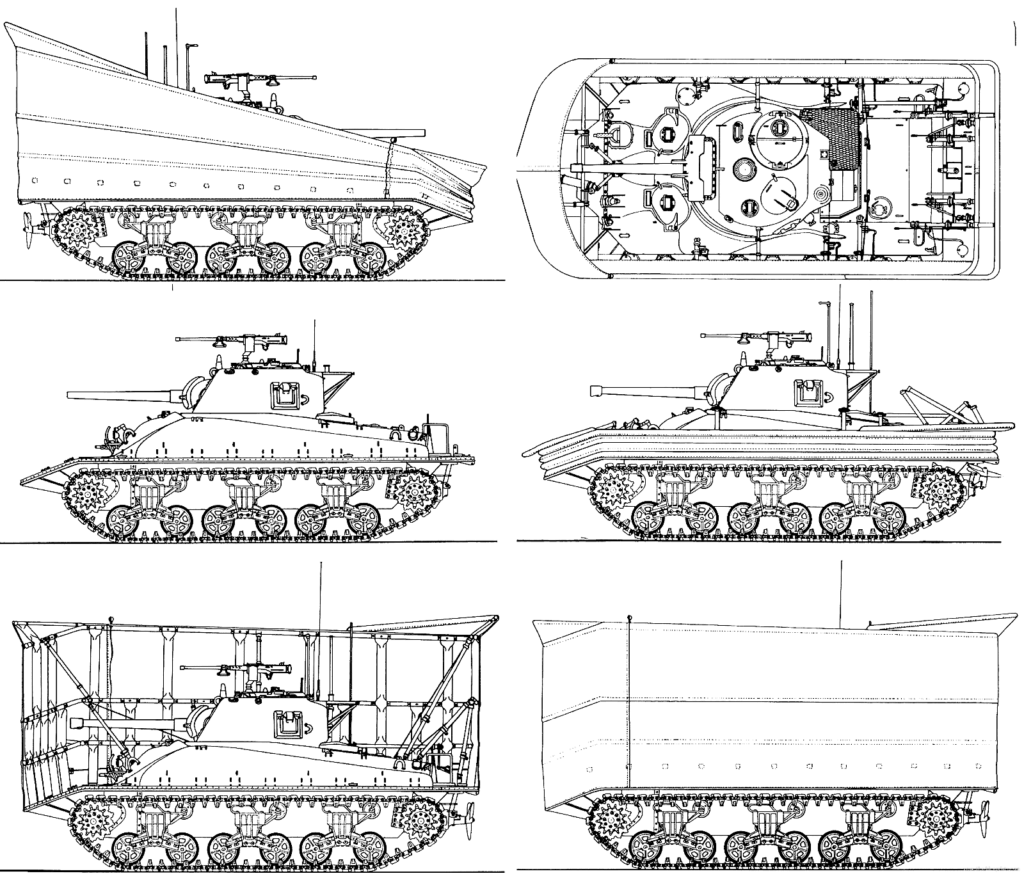

The Sherman DD is a modified M4 medium tank used by British, Canadian, and American forces. It weighs between thirty and thirty-three tonnes, as the conversion adds some weight. It measures roughly six metres in length, 2.7 metres in width, and about 2.5 to 2.7 metres in height with the turret and screen folded. When the crew erects the screen, the height increases as the canvas must rise above the turret roof to prevent swamping.

The armour matches the standard M4 Sherman. The hull front measures about fifty millimetres, and the turret front about seventy-six millimetres. The sides measure between thirty-eight and forty-five millimetres. The canvas flotation screen offers no protection. It exists only to keep water out of the hull.

The armament remains the 75-millimetre M3 gun with a coaxial .30-calibre Browning machine gun. DD crews avoid firing the main gun while swimming, as the tank becomes unstable. Once on land, the weapon is ready for action. Some conversions remove the bow gunner to simplify waterproofing and reduce weight. These tanks function with four crewmen instead of five. Ashore, the Sherman DD fights like a normal Sherman and offers strong fire support to the infantry.

Shermans use several engines. The M4A1 carries the Continental R975 radial engine of about 400 horsepower. The M4A4 uses the Chrysler multibank. Land speed remains between forty and forty-eight kilometres per hour. In water the tank reaches about four knots, roughly seven kilometres per hour. This speed suffices for short crossings but leaves the tank exposed during the swim.

The DD system on the Sherman is more complex. A mild steel boat-shaped platform is welded around the lower hull. It forms a base for the flotation screen. The canvas screen, made from heavy rubberised canvas, is supported by thirty-six vertical inflatable tubes and a set of horizontal metal hoops. High-pressure air bottles inflate the tubes in about fifteen minutes, even when the tank remains aboard a landing craft. Later tanks use an engine-driven compressor. When raised, the screen provides roughly one metre of freeboard in calm seas.

Two propellers, each between forty-five and seventy centimetres in diameter, sit at the rear. They swivel for steering and can be lifted clear of the water when the tank reaches land. The Sherman’s transmission sits at the front, so engineers route power to the props through the rear sprocket and idler wheels. Gears on the idlers feed power from the turning tracks into the propeller shafts. The driver controls the propellers hydraulically. The commander assists steering from a platform behind the turret using a large tiller. In shallow water, the crew collapses the screen by releasing air from the tubes, lifts the propellers, and allows the tracks to take over for the run up the beach.

All DD tanks receive extensive waterproofing. Crews seal the hull and engine intakes and rely on bilge pumps to clear small leaks. Each crew carries inflatable personal rafts and escape equipment. The flotation gear is considered expendable. Once ashore, the crew may tear away the screen and its supports to regain full visibility and turret traverse. Many tanks, however, keep the equipment for later amphibious operations, provided the gear remains usable.

| Multimedia |

| British DD Tank Schools |

During the war, Britain establishes a network of specialised DD tank schools to train crews in swimming operations. These schools operate under the 79th Armoured Division, famous for Hobart’s Funnies. In April 1943, responsibility for the Duplex Drive system passes to Major-General Percy Hobart. His division begins the task of training ten armoured units, including British, Canadian, and American regiments. The main training sites are located in England. Fritton Lake in the east and Stokes Bay on the south coast become the central training wings for the new amphibious tanks.

Fritton Lake, on the Norfolk and Suffolk border, is requisitioned in May 1943. The lake measures about four kilometres in length and is isolated enough for secret trials. From June 1943, crews attend two-week freshwater courses at Fritton. They learn the fundamentals of flotation, steering, emergency drills, and navigation in calm water. More than 1,200 men pass through Fritton Lake before the Normandy landings. The site remains valuable after D-Day. It becomes part of the Assault Training and Development Centre and later the Specialised Armour Development Establishment. Experiments continue there on river crossings, soft-ground operations, and new equipment designs.

After passing the Fritton Lake programme, crews move to the saltwater school at Stokes Bay, near Gosport. Stokes Bay serves as the advanced open-water training site from September 1943 to May 1944. Bay House and the Alverbank Hotel are taken over to house troops and instructors. Training lasts about three weeks. Tanks are waterproofed and checked on the beach before being loaded onto Landing Craft, Tank at the concrete hards. Each landing craft carries up to nine Valentine DD tanks. Naval crews then ferry the tanks into the Solent. At roughly 1.1 kilometres from shore, the tanks erect their flotation screens and launch. They swim towards Osborne Bay on the Isle of Wight. This coastal training gives crews realistic experience with wind, swell, currents, and the coordination needed between tank and naval crews. By May 1944, roughly 1,200 men have trained at Stokes Bay. The DD training programme in Britain is then considered complete, and the regiments move to their marshalling areas for the invasion.

Additional training sites appear as the war develops. Early in 1944, the United States establishes its own DD school at Torcross on the Devon coast next to Slapton Sands. Major William Duncan of the 743rd Tank Battalion, having trained on Valentine DDs in January, is ordered to set up this school. American crews begin arriving in March 1944. Two companies each from the 70th, 741st, and 743rd Battalions rotate through Torcross for intensive courses on Sherman DDs. The school works closely with United States Navy LCT flotillas based at Dartmouth. Training continues day and night through March and April. By the end of April, American instruction is complete. Reports record more than a thousand launch trials with very few tank losses.

DD tank training does not end with the Normandy landings in June 1944. Fritton Lake continues to serve as a centre for experimentation and refresher training. As the Allies advance towards the Rhine, British crews return to Fritton and then move to the River Humber at Burton-upon-Stather to practise swimming in stronger currents. As operations shift into the Netherlands and Germany, new forward training areas appear along the Maas and Waal. These allow regiments already deployed in Northwest Europe to sharpen their river-crossing skills close to the front.

Late-war records show that DD tank technology spreads even further. Valentine DD tanks are shipped to North Africa and the Middle East for planned operations that do not take place. By 1945, British forces in Asia are preparing to use DD Shermans in the war against Japan. The 25th Dragoons train on DD tanks in India in anticipation of landings on the Malayan coast.

From mid-1943 to 1945, the DD tank school network expands from secret lakes in England to rivers across Europe and even to training grounds in India. The system grows in step with the changing direction of the war and the increasing need for amphibious armour.

| U.S. DD Tank School |

The U.S. DD tank programme develops under intense pressure and at high speed. At the start of 1944, no M4 Sherman DD tanks exist in Britain, so early training relies entirely on the Valentine DD. That training runs from mid-January to mid-February. Major William Duncan of the 743rd Tank Battalion attends this course with several men from his unit. He is then chosen to create a dedicated Duplex Drive training school. His task is to prepare two companies from each of three American battalions. The 741st and 743rd Battalions are assigned to Omaha Beach, while the 70th Tank Battalion is allocated to Utah Beach.

Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Dean Rockwell of the U.S. Navy, commander of Group 35 of Flotilla 12, receives responsibility for the naval half of the school. He must supply the landing craft required for training and prepare the LCT crews for their invasion role. The school is set up at Torcross, beside the Slapton Sands training grounds, with the LCTs operating out of Dartmouth.

On February 27th, 1944, Colonel Severne MacLaughlin, commander of the 3rd Armored Group, issues a training plan for the 741st and 743rd Battalions. The tank companies will arrive without vehicles. Their DD Shermans will be issued at Torcross as they arrive from the United States. MacLaughlin hopes to run the course between March 20th,1944, and April 4th, 1944, provided the tanks reach Britain in time. Each battalion will train for five days.

The timetable soon proves impossible. The first fifteen DD tanks are not due until mid-March, and ten of these are destined for the British. Only five might be available for the start of training. Even these require urgent modifications, including changes to the supporting struts to prevent sinking. A larger batch of twenty-four DD tanks is expected in early April, but will arrive too late for the original schedule.

Launching DD tanks proves far more complex than expected. The flotation screens can snag on fittings within the landing craft and rip open. The propellers must avoid damage, so the LCT has to reverse at about 1,600 rpm while the tank drives off the ramp. As the tank leaves the ramp, it makes a short but deep plunge before the screen provides enough buoyancy to lift it. If the plunge is too deep, water can pour over the top of the canvas, and the tank sinks. To solve this, special ramp extensions are designed to guide the tanks deeper into the water before release. These delays slow both the Army and Navy preparations.

Formal training therefore extends well into April. On May 1st, 1944, Duncan and Rockwell each file detailed reports. Their findings match closely. Rockwell states that he has trained twenty-three of the twenty-four LCT’s needed to deliver the DD tanks of all three battalions. He urges that these craft be reserved exclusively for the invasion. He lists 1,087 launches from LCTs during training, with only two tanks lost and no personnel casualties.

Duncan reports that 250 DD tanks have arrived and been made ready. One hundred of these are used in training. His figures include more than 1,200 launches from LCTs, 500 launches from land, and 800 hours of water navigation. He records six non-fatal cases of carbon-monoxide poisoning, three tanks lost, and three men killed.

Many of the officers’ shared recommendations later prove critical. They argue that DD tanks must never be launched more than 3.7 kilometres offshore. They insist that the decision to launch should rest with the senior Army officer present. They also recommend that DD operations be limited to wind and sea conditions no worse than Force Three.

Records differ over whether DD tanks take part in the full-scale rehearsals for Utah and Omaha Beaches. Because the Duplex Drive system remains highly secret, some commanders prefer not to risk exposing it. On March 25th, 1944, Major General Clarence Huebner of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division advises that the DD tanks remain at Torcross rather than join the coming rehearsal. Yet Rockwell’s final report states that thirty-one DD tanks launch during Exercise Tiger, the main Utah Beach rehearsal. DD tanks are also believed to participate in Exercise Fabius I, the Omaha Beach rehearsal, though direct confirmation remains elusive.

After the school closes, training does not end. Crews continue to practise sighting, gunnery, and final checks on their new equipment. Rockwell continues to drill LCT crews, including the last of his primary craft, LCT 713. He also trains several backup craft. When the invasion force departs, all twenty-three of the original LCT’s, together with the late-arriving 713, embark as a single, fully trained group for D-Day.

| Training Methods |

Training at the DD tank schools is demanding and innovative. Crews must master armoured warfare and nautical skills at the same time. Instruction is divided into clear phases. Basic work is carried out on land and in calm water. More advanced training follows in open sea conditions and alongside naval and infantry units. Safety, maintenance, and careful handling of the unique DD equipment remain constant priorities.

The tanks used in training depend on availability. At first, the British rely on the Valentine DD. These Valentines are Mk II or Mk V hulls fitted with Straussler’s flotation screen and a single propeller at the rear. The tanks are reliable, though underpowered, and are available in numbers. They are also expendable by 1943, as the Valentine is becoming outdated in battle. By late 1943, the Sherman DD begins to replace it. The Sherman offers a higher freeboard, twin propellers, and a gun turret ready for action the moment the tank lands. British DD conversions use Sherman III and Sherman V models. American crews prepare on M4A1 Shermans.

The flotation screen defines the Duplex Drive system. It is a waterproof canvas curtain fitted around the hull. When the tank prepares to swim, compressed-air bottles inflate dozens of rubber tubes that stand inside the screen. Metal struts and hoops support the structure. The process takes about fifteen minutes. Once deployed, the screen rises to a height that gives about one metre of freeboard. Only the upper canvas band appears above the sea. The tank itself remains hidden below the waterline. Propellers drive the tank in water. The Valentine DD uses a single screw, while the Sherman uses two and can manage about seven kilometres per hour in calm conditions. Steering comes from the driver, who swivels the propellers hydraulically, and the commander, who stands on a small platform behind the turret with a long tiller. A DD tank behaves as a hybrid craft. Crews must handle it comfortably on land and in open water.

Training at Fritton Lake begins with classroom work and practical instruction. Crews learn to waterproof engines, seal vents, prepare bilge pumps, and inspect the flotation gear. They practise erecting and collapsing the screen and fitting the propellers. They switch the tank from land mode to sea mode and back. Navigation and manoeuvring drills take place on the lake. Instructors mark courses with buoys across the two-and-a-half-mile stretch. Drivers learn how wind and minor currents affect their tank. Mock LCT ramps on the lakeshore allow practice launches from a fixed incline into the water. Crews rehearse beaching drills, learning how to climb ashore without swamping the tank.

Safety instruction is essential. Crews train with the Amphibious Tank Escape Apparatus, a small breathing device that helps them escape from a submerged hull. Fritton Lake includes cut-down hulls placed in special dunking tanks. In these simulators, crews sit inside as water flows in. They must open the hatches, exit underwater, and swim free. These drills save lives. One Sherman DD still lies at the bottom of Fritton Lake as a reminder of the risk.

After about two weeks at Fritton, troops advance to Stokes Bay. The coast presents new challenges. Training here lasts a further three weeks. Naval involvement is far greater. Tank crews work closely with LCT crews. A typical exercise uses real landing craft. Tanks are loaded at the beach hards, taken into the Solent, and launched in open water. Launching is the most hazardous part of the operation. The LCT can tear the screen if the tank snags on a fitting. The landing craft must reverse at about 1,600 rpm while the tank drives off the ramp. If the tank drops too sharply on leaving the ramp, it plunges below the height of the flotation screen and floods. Special ramp extensions are therefore fitted to support the tank a moment longer. These reduce the depth of the downward plunge and increase the chance of a clean entry. By spring 1944, these methods greatly improve success rates.

At Stokes Bay, crews practise formation swimming across the Solent. Tanks form in line or echelon and cover roughly one to one-and-a-quarter kilometres to the Isle of Wight. These swims replicate the distance expected on D-Day. Crews maintain spacing, steer to set bearings, and land on designated beaches. After each run, tanks pass through a wash-down pool to remove saltwater. Mechanics inspect the screens, engines, and propellers. Repeated drills at sea, carried out in various weather, give the crews confidence.

Combined training follows. DD units take part in large-scale rehearsals with infantry, engineers, and naval forces. Some move to the Moray Firth in Scotland or Barafundle Bay in Wales. Here, they practise full assault landings with beach obstacles and follow-on infantry. Conditions can be hazardous. During Exercise Smash at Studland Bay on 4 April 1944, rough seas rise without warning. Six Valentine DD tanks swamp and sink. Six men drown. The accident leads to new rules: tanks must not launch in conditions above Sea State Three, and the senior Army tank officer must make the final decision on launching.

By early June 1944, the crews have trained on lakes, in open seas, on beaches, and in live-fire rehearsals. They know how to fold the floats, how to escape a sinking tank, how to launch correctly, and how to swim in formation. They are as ready as training can make them for the conditions they will face in the assault.

| Units Trained and Operational Role |

The DD tank schools ultimately prepare a select group of Allied armoured units for amphibious operations. By the summer of 1944, ten regiments or battalions have trained on Duplex Drive tanks. Five British regiments, two Canadian armoured regiments, and three American tank battalions complete the programme. Their training shapes the opening hours of the Normandy landings and influences later river-crossing operations across Northwest Europe.

Hobart’s 79th Armoured Division forms a dedicated DD Brigade. The brigade includes the 4th/7th Dragoon Guards, the 13th/18th Royal Hussars, the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry, the East Riding Yeomanry, and the 15th/19th King’s Royal Hussars. Canada assigns the 1st Hussars and the Fort Garry Horse to the DD programme. The United States Army trains the 70th, 741st, and 743rd Tank Battalions on Sherman DD tanks during the spring of 1944.

| Operational Use in World War II |

After almost two years of development and training, DD tanks enter combat in 1944. They take part in several major amphibious operations in Europe. Their use brings mixed results. Some landings succeed. Others expose the limits of the system.

| Operation Overlord |

The Normandy invasion on June 6th, 1944 becomes the defining test of the DD tanks. The Allies assign DD Shermans to lead the assaults on several beaches. Eight tank battalions in British, Canadian, and American service receive DD equipment. Each landing craft carries four or five DD tanks for a planned seaborne launch. The intention is to launch between 1.8 and 4.5 kilometres from shore. The tanks are to swim ahead of the infantry and provide fire support as soon as they reach the sand.

On the British and Canadian beaches, most DD tanks arrive successfully. At Sword Beach, the 13th/18th Royal Hussars launch their tanks about four kilometres offshore. One tank loses its screen and must land by craft. Another sinks after a collision with a landing craft. The rest swim ashore and support the assault troops. At Gold Beach, the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry also cross without major incident because the sea is calmer in that sector. At Juno Beach the surf is heavier. Some DD tanks swamp or drift off course. Many still reach land and support the 3rd Canadian Division. Tanks of the 1st Hussars land in the first wave. One troop sinks after launching too far out. Even so, at least twenty-one Canadian DD Shermans operate on Juno soon after H-Hour and help secure the beachhead. British and Canadian commanders later state that amphibious tanks and other specialised vehicles reduce casualties and accelerate the advance inland. By 09.30, infantry on Sword Beach advance about 2.4 kilometres inland with tank support. In contrast, troops at Omaha struggle to gain even a few hundred metres in the same period.

At the American Utah Beach, planning is more conservative. The U.S. 4th Infantry Division launches its DD tanks only 550 to 730 metres offshore. Naval support craft guide them during the crossing. Most of the twenty-eight DD Shermans reach the beach. Only two sink. The tanks provide immediate fire support. Utah Beach is secured with relatively low casualties by midday.

Omaha Beach presents the opposite experience. Conditions off Omaha are rough. Currents are strong. The 741st Tank Battalion launches twenty-nine DD Shermans about 4.5 kilometres from shore. Almost all are lost. Twenty-seven sink in the heavy swell before reaching land. Waves overwhelm the screens. Some tanks drift sideways to the waves and are swamped. Only two reach the beach under their own power. A few more arrive later when delivered directly onto the sand by landing craft. The near-complete loss of the battalion deprives the first assault waves of armour. The infantry face intense fire with little support. Casualties rise sharply. Progress is slow and depends on later landings of conventional tanks. Post-battle reports blame the disaster on launching too far out, poor sea conditions, and the low freeboard of the screens. Some crews launch at an angle to the waves rather than head-on, making swamping more likely. The experience earns the DD tanks a harsh reputation on Omaha. Crewmen refer to them as floating coffins.

Despite the failure at Omaha, the DD tanks prove their value on other beaches. They help open exits on Sword, Juno, and Gold. General Eisenhower later remarks that Hobart’s specialised armour, including the DDs, is frightening to the German defenders and vital to the assault. German commanders express surprise at the sight of tanks swimming ashore on June 6th, 1944.

| Operation Dragoon |

DD tanks next enter combat in Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of the French Riviera on August 15th, 1944. Three American tank battalions, the 191st, 753rd, and 756th, receive thirty-six Sherman DDs for the landings between Toulon and Cannes. The Americans apply lessons learned during the Normandy assault and use the tanks with greater caution.

The 756th Tank Battalion launches eight DD Shermans about 2.3 kilometres offshore. The sea is calm and conditions are favourable. Most of the tanks reach the beach without difficulty. One DD is swamped when the bow wave of a passing landing craft collapses its screen. Another strikes an unseen underwater obstacle and sinks. The remaining six tanks swim ashore and support the landing troops.

The 191st Tank Battalion adopts an even safer method. The crews decide to land their twelve DD tanks almost directly on the beach. Some enter the water in very shallow surf. Others run straight off ramps onto the shoreline. All twelve reach land intact. Once ashore, however, they move into a minefield. Five tanks from Company C strike mines and become immobilised. Their crews remain unhurt and continue fighting from the disabled vehicles as improvised gun positions.

The 753rd Tank Battalion fields sixteen DD Shermans. The battalion launches eight of them at sea, and all eight swim to the beach without incident. The remaining eight tanks stay aboard their landing craft until the beach is secure, then land directly without risk.

In total, only two DD tanks are lost in the water during Operation Dragoon. This record is far better than the losses at Omaha Beach. The DD tanks provide steady fire support as American and Free French troops advance from the French Mediterranean coast. The landings face lighter resistance than Normandy, so their role receives less attention. Even so, they help overrun coastal positions quickly and assist the infantry during the early hours of the assault. At least one DD Sherman is lost before the operation. The 753rd Battalion loses a tank off Salerno during a rehearsal in July 1944.

| Operations in the Netherlands and Northwest Europe |

After the invasion of France, British forces continue to employ DD tanks in specialised amphibious tasks. These missions focus on river and estuary crossings in the Netherlands and northern Germany.

In late October 1944, the Staffordshire Yeomanry, newly converted to DD tanks after D-Day, conducts one of the longest operational swims of the war. The regiment swims its Sherman DDs across the Western Scheldt estuary during the Battle of the Scheldt. The crossing covers about eleven kilometres. Remarkably, all tanks complete the water passage without sinking. The landing zone, however, is extremely muddy. Fourteen tanks bog down immediately on the far bank. Only four tanks manage to move and fight on South Beveland. The crossing still achieves surprise, but the marshy terrain limits the unit’s combat usefulness on arrival. The episode shows that survival at sea does not guarantee mobility ashore.

The Rhine crossing in March 1945 becomes another major test. Operation Plunder begins on March 23rd, 1945, as British and American forces carry out a coordinated assault across the Rhine River. British units, including the 44th Royal Tank Regiment and the Staffordshire Yeomanry, launch DD Shermans at night. American tank battalions, the 736th and 738th, do the same. The river has a strong current. The launch points are placed upstream so that the tanks drift into their planned landing zones. The Allies prepare the far bank in advance. Amphibious Buffalo vehicles land engineers who lay portable mats on the muddy German shoreline. These mats prevent the tanks from sinking when they emerge from the water. Some DD tanks are lost in the wide river. Reports describe several sinking, though figures vary. Most tanks, however, reach the far bank and help form bridgeheads on the eastern side. Commanders later note the psychological effect of tanks appearing out of the dark on the enemy shore.

The last combat use of DD tanks occurs in late April 1945. During the final advance into northern Germany, the Staffordshire Yeomanry swims Sherman DDs across the Elbe River at Artlenburg on April 29th, 1945. This operation becomes the final amphibious swim by DD tanks in the war. German resistance is collapsing by this time. The DD tanks cross under concealment and support the securing of the far bank. No significant losses are reported. The crossing marks the end of the DD tanks’ combat service in Europe.

| Italian Campaign |

In the river-cut terrain of northern Italy, DD tanks finally enter combat during the closing weeks of the war. By early 1945, the British 7th Queen’s Own Hussars train on DD Shermans and a small number of Valentine DD’s. The spring offensive requires repeated crossings of major rivers, and the regiment uses its amphibious tanks to overcome these obstacles.

On April 24th, 1945, DD Shermans assist the assault across the Po River, the largest river in northern Italy. The crossing succeeds. The tanks reach the far bank and provide direct fire support to the infantry as soon as they land.

Four days later, on April 28th, 1945, the 7th Hussars reach the Adige River. Many of the DD Shermans have already fought hard in the advance. Some are damaged, yet those still able to swim take part in the assault crossing. The regiment uses the tanks to carry troops across the water under fire. Valentine DDs also appear at the Adige. They are pressed into service as improvised fuel carriers. This becomes the only recorded combat use of Valentine DD’s. Their flotation screens allow them to shuttle fuel across the river to supply the Sherman tanks now fighting on the far side.

After crossing the Po and the Adige, the DD tanks continue the advance towards Venice. No further amphibious operations are required. German forces in Italy surrender on May 2nd, 1945. In the final pursuit, crews discover a practical use for the folded screens. The collapsed canvas forms a wide platform on the tank roof. Tanks often carry many infantrymen on these makeshift decks, turning the DD Shermans into temporary troop transports as the advance accelerates towards victory.

| Sources |