| Page Created |

| November 10th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| November 19th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Special Pages |

| Special Raiding Squadron |

| Related Operations |

| Operation Mincemeat Operation Turkey Buzzard/Operation Beggar Operation Narcissus Operation Husky Operation Husky, Special Raiding Squadron Operation Husky No. 1 Operation Ladbroke Operation Ladbroke, Coup de Main Operation Husky No. 2 Operation Fustian Operation Chestnut Special Raiding Squadron, Raid on Augusta |

| July 9th, 1943 – July 10th, 1943 |

| Operation Husky, Special Raiding Squadron |

| Objectives |

- attack and destroy the Lamba Doria gun battery.

| Operational Area |

Maddalena Peninsula, Sicily

| Allied Forces |

- Special Raiding Squadron

| Axis Forces |

| Preperations |

The Special Raiding Squadron departs from Egypt in early April, arriving at Azzib, Palestine, after a slow and monotonous journey of over forty hours. They arrive at around two in the morning, resulting in the chaotic process of unloading in complete darkness. There is no station, and the group finds themselves on a grassy verge beside the tracks, disoriented and weary. However, the arrival of unit transport, which had accompanied the advance party, soon brings some order, and the men are ferried to camp. Eventually, a tent is found, and they settle down to rest.

The following morning, they wake up late and survey their surroundings. About 800 metres away, the sea is visible, with the coast road running along a hill near the camp and bordered by orange groves, a refreshing sight compared to the arid landscapes of Egypt. Inland, the coastal hills of Palestine rise beyond a two-mile-wide strip of cultivated land. The camp itself is centred on the hilltop, with the various messes and cookhouses situated there, while tents for the men’s lines are spread neatly across the slopes, arranged by troop.

The camp is located on the coast road, approximately 32 kilometres north of Haifa and 5 kilometres south of the Syrian border. A small village, Azzib, lies just north of the camp, while a Jewish holiday resort, Nahariya, lies to the south. Around midday on the first day, a meeting of all the officers is called to outline the training procedures. The nature and duration of the training remain undisclosed, but it is made clear that, due to the varied backgrounds of the men, training must start from scratch, assuming no prior knowledge. Thus, all men are required to complete a second round of recruit training before advancing to more specialised skills.

The new organisation and role of each sub-unit are also detailed. Each troop is divided into three sections, which are further divided into two equal sub-sections, each commanded by a corporal or lance sergeant. These sub-sections consist of three parties of specialists: the light machine gun (LMG) party, the rifle party, and the rifle-bomber party, each comprising three men. This structure ensures that each sub-section functions as an efficient, self-sufficient fighting unit.

At this point, the Special Raiding Squadron consists of 18 officers and 262 enlisted personnel. The Headquarters is led by Major Mayne as Commander, with Major Lea serving as Second in Command. Captain Francis manages administrative duties, while Captain Gunn fulfils the role of Medical Officer. Captain Melot is responsible for intelligence, and Captain Muirhead commands the Mortar Platoon, which includes 28 men. The unit’s chaplain, Captain Robert Lunt, has recently been appointed.

No. 1 Troop operates under the leadership of Major Fraser, supported by Captain Wilson and Lieutenants Riley and Wiseman, who each command a section. Captain Poat directs No. 2 Troop, with Captains Marsh and Lieutenants Davis and Harrison in charge of sections. No. 3 Troop falls under the command of Captain Barnby, assisted by Captain Lepine and Lieutenants Gurmin and Tonkin as section leaders. Additionally, a small contingent of Royal Engineers is attached to the Squadron, providing essential technical support.

Training is conducted near the beach, across a thin line of sand dunes and scrubland separating cultivated land from the sea. This rough terrain, intersected by the coastal railway, proves ideal for training due to its ample cover and natural sand dunes for firing practice. The area is only a five-minute march from camp, allowing for easy access. The first month is focused on physical fitness, basic skills, and familiarisation with equipment and loads. Gradually, a complete scale of arms, ammunition, and equipment is developed for each sub-unit, assigning specific loads to individual soldiers.

Although Raiding Forces Headquarters, which controls both the Special Raiding Squadron and the Special Boat Section, oversees administrative aspects of training, the Special Raiding Squadron maintains practical independence. Paddy Mayne insists on full control of the squadron’s activities, leaving Raiding Forces Headquarters largely uninvolved. During this period at Azzib, Bill Fraser rejoins the unit, as does Sergeant Johnny Cooper, who previously escaped captivity after being captured with Stirling’s party. Cooper and Sergeant Mike Sadler had walked to First Army lines, unarmed and subjected to various dangers, including an attack by hostile locals, before being flown back to the Eighth Army.

During the initial training phase, officers have ample opportunity to become familiar with their sections and assist in training. The presence of experienced Non-Commisioned Officers proves invaluable to the green officers. In one section, Sergeant Andy Storey, ex-Scots Guards and a stoic Yorkshireman, provides steadfast leadership, while Corporal Bill McNinch, a charismatic leader and humourist, has a more animated personality and is popular with the men. Corporal Bill Mitchell, another experienced Non-Commisioned Officer, offers reliable support, having previously served under the section officer in Syria.

After about a month of rigorous training, it is deemed that a satisfactory standard has been reached in basic skills, and the focus shifts to more advanced aspects of preparation. Physical fitness remains a priority, and the first major test is a forced march from Lake Tiberias, 183 metres below sea level, over the coastal hills back to the camp, a distance of 72 kilometres. Each of the three troops carries out the march independently. No. 3 Troop, the first to undertake the challenge, finds it particularly arduous, with only eight men completing the journey. No. 1 Troop fares better but loses time by taking a wrong turn, returning to camp almost forty-eight hours later.

When it is their turn, the remaining troops leave camp by truck in the morning and arrive at Lake Tiberias at midday, beginning the march in sweltering heat. The journey proves gruelling, climbing through thick cornfields without respite. The initial descent to a small stream is a welcome relief, though orders prohibit drinking water without command permission. The midday sun grows increasingly oppressive, leading to frequent halts as men succumb to heat exhaustion. Eventually, the decision is made to rest until the evening.

The march resumes at dusk, and they soon reach a village, stopping by a stream to cook a simple meal using lightweight rations devised by the intelligence officer, which include oatmeal, dried lentils, and bacon. Following a short rest, they resume the march, continuing through another village before encountering a steep climb up a mountain road that zigzags into the darkness. Exhaustion sets in, but the men find motivation in singing together, covering over 32 kilometres that night.

By dawn, they stop near a Palestine police barracks to rest and wash. Having covered 51 kilometres in 18 hours, only five or six men have dropped out, but many suffer from sore feet and blisters. The next part of the journey proves particularly challenging, especially with an assault on an old ruined castle lying on their route. Upon reaching the castle, they find it abandoned, leaving rude notes on the walls for the absent defenders before resuming the march.

The final stage of the journey is the most difficult. Walking through a gorge along a riverbed offers initial relief, but the water softens their feet, making every step painful. Eventually, they reach the open plain leading to camp, a further 5 kilometres away. Weary and aching, they press on under the blazing sun. At the approach to camp, the officer in charge decides to make a final effort, ordering the men to slope arms and form into threes. Despite their exhaustion, they march into camp in good order, completing the march of 77 kilometres in 26 hours.

The Tiberias march is a foretaste of the intensity of training still to come. Shortly afterwards, a group, including officers and a dozen men, is sent to Jerusalem to attend the Grant-Taylor revolver course. The course is overseen by Bob Merlot, the unit’s intelligence officer, whose friendly and patient nature earns the respect of all. Sandy Wilson, known for his clumsiness but with a heart of gold, also joins the group, providing some light relief.

During the Jerusalem trip, one soldier, Sturmey, has too much to drink and confronts a major about his unauthorised parachute insignia, resulting in a night in the guardroom. However, it turns out the major is indeed an imposter, avoiding a court-martial for Sturmey.

Upon returning to camp, they find it buzzing with activity. During their absence, the regiment is visited by General Dempsey, who reveals that they will participate in an operation involving an amphibious assault to capture a coastal gun battery, an essential part of the larger mission. Training intensifies, with a focus on practising cliff climbing in silence and preparing for the assault.

Training also includes the use of horses and mules, and some officers begin taking riding lessons, though enthusiasm wanes after a particularly difficult training day. By mid-May, there is a sense of urgency as the troops are briefed on the upcoming mission. The plan involves No. 1 and No. 2 Troops landing and clearing enemy positions while No. 3 Troop cuts off the main road. This process is rehearsed repeatedly until the drills become second nature. Much attention is paid to improving marksmanship and speed, with competitive shooting used to enhance skills.

One of the final training exercises involves practising with live ammunition, with spectacular tracer fire creating an impressive visual display. This, however, attracts the attention of a passing Allied aircraft, leading to a reprimand for supposedly firing at friendly planes. Alec Muirhead, tasked with training a mortar section despite his lack of experience, improvises a highly effective approach. Despite some miscalculations, including an incident where mortars nearly hit their own position, the training pays off, and the men prove capable and efficient.

As training concludes, the squadron reaches a peak of efficiency. They are prepared physically and mentally, with every man aware of his role. They depart Azzib on June 6th, 1943 for an undisclosed destination, confident in their readiness for the mission ahead.

The final night before departure sees much celebration, with officers and men indulging in liquor and borrowing Jeeps for final trips to Haifa. Remarkably, despite the chaos, all personnel make it to the station for departure. As dawn breaks, they begin their journey, uncertain of their destination but eager to face whatever lies ahead, confident in their abilities and determined to succeed in the mission awaiting them.

| Final Preperations |

The troops of the Special Rading Squadron gather at Suez at dawn, uncertain of their destination. Even when they arrive, they wait on the platform for hours, still guessing about their immediate future. The certainty of soon being deployed operationally grows when they hear that they will all be transferred onto a ship. It seems evident that they will be sailing towards their unknown destination within a few days.

Tenders carry the men to a ship, a sleek and fast steamer weighing about 3,000 tonnes. The ship, named the Ulster Monarch, was once a passenger ferry crossing between England and Northern Ireland before the war. Now, repurposed by the navy, she serves as a Landing Ship for Infantry, equipped with six assault landing crafts that can be lowered fully loaded into the water when the time comes. With the white ensign flying proudly, she exudes an air of order and efficiency, nothing like a simple ferry. The men are unaware at this time that the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch will be their home for the next five weeks, and a comfortable one at that.

The crew consists of a dedicated group of officers and ratings, and inter-service cooperation quickly becomes evident. Respect grows between the troops and the navy, and both parties “muck in” seamlessly. The soldiers do not get in the way of the crew, nor the crew in theirs. Friendships form, and the cooperative atmosphere becomes the prevailing spirit of the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch. Each officer is given a small cabin, and the men settle into spacious mess-decks, finding more comfort compared to the overcrowded troopships of the past.

A week later, conditions further improve when No. 3 Troop transfers to another ship, the Dunera. The first few days at Suez are spent aboard the ship, and ample opportunities arise to study aerial photographs and the final details of their objective. Mornings are dedicated to physical training and arms inspections, while the rest of the time is spent reviewing operation details with the section.

Special training takes place in the afternoons, the reason they were transferred to the ship well before the operation’s D-Day. The H.M.S. Ulster Monarch is equipped with six Landing Craft Assault that will carry them onto the beaches. During practice, the Landing Craft Assaults are lowered just opposite the doors of the mother ship, and the men climb aboard. The Landing Craft Assaults are lowered into the water and then cast loose. The Landing Craft Assault crews consist of sailors from H.M.S. Saunders, and a sense of camaraderie is immediately formed as they recognize each other from their days near the camp at Kabrit. These Saunders men take pride in their role, confident they will land the soldiers at the designated location, regardless of the resistance faced.

Entering the boats is a challenge, particularly on a dark and turbulent night with the ship in motion. If the boat is lowered unevenly, there is a risk of it being swamped, or it might crash against the side of the mother ship if not quickly cast loose. The navy personnel, however, are well-trained, and it is crucial that the troops become familiar with the embarkation drill to avoid any errors due to inexperience.

Though the Landing Craft Assault might seem small and fragile to the untrained eye, it is not the case. Weighing 3 tonnes and powered by twin engines, it is no lightweight craft. The Landing Craft Assault can carry 20-30 fully equipped troops, in addition to its crew of two or three, and is armored to protect against small arms fire. With a draft of only 0.6 meters, it is ideal for landing troops on hostile shores under the cover of secrecy and surprise.

Once the men understand the boarding order and their positions, they are ready for embarkation. The next task is disembarkation and beach drills, which are practiced every afternoon. Their positions within the Landing Craft Assault are carefully planned so that, as soon as they reach the shore, the section can disembark as a combat-ready unit. Each sub-section occupies either side of the LCA, with the section headquarters in the middle. Upon landing, the officer leads headquarters up the beach to establish a defensive vantage point for the whole section. These drills are repeated until perfection is achieved.

After spending a few days aboard the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch, the men receive news of a full-scale rehearsal of the operation at Aqaba, an isolated and rugged area at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, where Sinai, Palestine, and Transjordan meet. Every aspect of the rehearsal is treated like the real thing. Maps and aerial photographs of Aqaba are distributed, and thorough operational planning ensures that everyone knows the objective. The men learn the terrain thoroughly, and one morning they sail under active service conditions.

Aqaba is an austere sight, with vivid blue waters contrasting sharply with the glaring sandy mountains. The harbour is flanked by palm trees, with just a few native huts, emphasizing the poverty of the region. That evening, the rehearsal takes place. The men embark on landing crafts at 23:00, and the blackness of the shoreline contrasts against the dark sea. They land silently and swiftly form up to move towards their objective, an imaginary gun battery atop a steep mountain.

The ascent is grueling, with dislodged stones clattering down and the slope’s steepness making it hard to avoid slipping. The mountain’s convex shape, however, keeps them out of sight from the defenders. The men approach within 75 metres of the top, preparing for an assault when the silence is broken by their commander’s irate voice. Spurred on, they launch a double-time attack, surprising the defenders, who have been waiting for their slow approach.

The exercise proceeds with blanks, lights, noise, and confusion until they consolidate on top and begin the even tougher descent back down. As dawn breaks, they signal for landing crafts to return them to the ship.

Returning to Suez, they spend three more weeks waiting, often doing nothing. General Montgomery visits to inspect the troops and eventually realizes they are the unit that operated behind enemy lines in the desert. The realization prompts him to deliver his characteristic motivational speech, stating how crucial their contribution was to the advance to Tripoli. The men, skeptical of his hyperbole, refrain from cheering until he is in his launch, causing some confusion but ultimately bringing cheers drifting across the water.

The Derby is held one afternoon, and they organize a sweepstake. During a practice exercise, each section works with the No. 38 transmitting and receiving sets. The aim is to ensure each operator understands the drill, particularly the procedure for radio communication. One of the runners, Percival, finds it challenging and, with earphones on, often ends up shouting messages unintelligibly during the exercises, much to the section’s amusement. His idiosyncratic responses lighten the atmosphere in an otherwise demanding training environment.

Later, the men undergo an endurance march at night. Despite being lightly loaded, the march is exhausting and monotonous, exacerbated by the uninspiring surroundings. The intense mental challenge is as much a part of the exercise as the physical strain. Paddy, the leader, keeps a relentless pace, his long stride effortlessly overtaking them. Though Paddy remains sympathetic and encouraging, he pushes the men hard to ensure they develop operational stamina.

An experiment is conducted on them during the march. Some troops are given Benzedrine tablets to gauge whether these stimulants would enhance their physical endurance. Paddy observes marked improvement in the selected men, who begin to march energetically and sing after previously showing signs of fatigue.

While in Suez, a final training exercise is carried out. The men are assigned to attack a coastal anti-aircraft battery. No. 3 Troop cuts the road, while the others detour along the beach to mount a flank attack. The attack succeeds, with the gunners completely surprised by the diversion. They admit that they did not see the flank attack coming.

The wait in Suez stretches on, with Paddy Mayne occasionally waking officers in the middle of the night for drinking sessions. One such gathering turns into an impromptu operational briefing. Paddy, uncharacteristically eloquent, clearly and confidently runs through the entire plan of the operation while standing over a relief model. The officers, initially drowsy, are engaged as Mayne explains every aspect of the mission. Though it starts as a drunken social, the night turns into an effective and beneficial tactical lesson.

Each day, the sense of impending action looms larger. The waiting becomes harder, and as the days pass, the strain builds. The men know it is coming soon, but cannot pinpoint when. They are unable to make plans beyond the next few hours, always anticipating the next command. Finally, one day, the ships begin moving, reshuffling their positions. One by one, they disappear into the entrance of the Suez Canal, signaling that the time has come.

Soon, the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch also enters the canal. As they move through the canal, their predominant emotion is one of relief, the anticipation, the uncertainty is finally coming to an end. The troops watch the banks of the Suez Canal drift past with a sense of excitement. In the distance, they spot their old camp at Kabrit and wave goodbye as they move through the Great Bitter Lake. As they round the ‘Point’, the men from HMS Saunders wave enthusiastically, exchanging banter with the Saunders personnel manning the landing craft on board. The good wishes shouted from the shore suggest that even those on land are unaware of the destination, just like the troops.

The day passes quickly, and by the afternoon they arrive at Port Said. Here, they find a large fleet of liners, cargo ships, and escort vessels assembled, all presumably headed for the same mission. It is only now that they begin to understand the scale of the operation. Around them are massive ships, fully packed with troops and landing craft, ready for deployment. The navy is active, with corvettes, destroyers, and landing craft busily moving around. Port Said is much smaller than Suez, which makes the packed ships and tight formation all the more impressive, underscoring the size of the invasion fleet.

The next day, they are informed that the entire invasion force will be allowed ashore instead of staying aboard all day. For security reasons, this is done in an organized manner, though the effort involved seems hardly worth it. Badges, decorations, and regimental insignias are removed, though it seems unlikely the Germans would be particularly interested in individual unit identifications. Marching through Port Said, the troops feel like they are simply drawing attention to their presence and strength, essentially advertising the invasion force. The only explanation they come up with is that Montgomery must be so confident in the mission’s success that he doesn’t mind if the enemy knows they are coming.

The sight is impressive, a seemingly endless line of units from different nations marching through the palm-lined streets of Port Said. Locals gather to watch, and the troops wonder what they might be thinking. They speculate if someone is secretly transmitting messages to Germany as they parade through the city.

After some confusion and a long wait for a ferry, they eventually make it back to the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch and the troopship H.M.T. Dunera. From that point, the atmosphere shifts to one of tension and anticipation. The men know the wait is almost over. The next morning on July 5th, 1943, at 11:00, they leave the harbour, heading out into the Mediterranean. They are far from alone, as ships ahead and astern maneuver into formation. Once in convoy, they begin moving along the Egyptian coast towards their still-unknown objective.

Once at sea, the destination is no longer a secret. They are given a small blue booklet containing everything a soldier or tourist might need to know about Sicily, the stepping stone to Europe. Many had already suspected Sicily was the target, and now, with the booklet in hand, the pieces fall into place.

From the map, they learn their landing site is a foot-shaped promontory on the southeastern coast of Sicily, about eight kilometres south of Syracuse, which is one of the initial targets.

Officers are summoned for a final briefing, and last-minute aerial photos are distributed. The ship turns into a hive of activity as everyone realizes that time is running out. The photos are scrutinized both individually and collectively, and a relief model of the objective area is passed around the sections. Back in Azzib, they had planned and rehearsed the general attack strategy, which is now refined down to the smallest detail—from troop to section, section to sub-section, and down to individual soldiers. Each man knows his role, his expected position, and which flank to cover. The operation is so meticulously planned that it could proceed without a single order once they land and begin the assault on the gun positions.

The photo analysis is very thorough, almost too thorough, leading to conflicting interpretations. One particular mark on a photo causes debate, and nobody can determine what it is. A figure nearby is studied, if running away, it might indicate an ammunition dump; if running towards, possibly an air raid shelter. But they can’t agree which direction the figure is moving. Later, they find that the mysterious object was nothing more than a haystack.

On the practical side, the troops are also busy. Equipment is sorted and distributed evenly, weapons cleaned and loaded, grenades primed, and protective coverings prepared for gear to withstand seawater. Various improvisations are made, oiled silk for valuables, and rubber items to protect weapon muzzles and watches. After final checks and fittings, they are ready. Each man is given an inflatable ‘Mae West’ life belt, in case they have to swim, an unsettling thought given they are each carrying almost 36 kilograms of gear.

With preparations finished, there is nothing left to do but wait and discuss the operation. The scene around them is deceptively peaceful, the sun shines on the calm blue-green Mediterranean, and the Libyan coast appears faintly on the horizon. Ships steadily advance towards the enemy shores, hoping to remain undetected.

The hope for a surprise landing lingers, though they doubt it is possible given the scale of the operation. A single enemy aircraft could easily compromise the mission. During the five-day voyage, tension mounts, with anxious glances frequently cast skyward, hoping enemy planes stay away. The tension peaks as they pass Crete, knowing the threat is highest there. But, miraculously, they remain unnoticed. There is a report that a four-engine reconnaissance plane, possibly a Focke-Wulf, flew over, but there is no attack. Later, they learn that the Special Boat Squadron had been tasked with raiding Crete to keep enemy aircraft grounded, likely the reason for their safe passage.

Sailing towards Sicily is uncomfortable, and waiting for battle is the hardest part—anxiety and inactivity dominate their minds. It is difficult to resist dark thoughts, and fear of the unknown takes hold. They wonder who among them might not return. Letters and photographs are packed away, perhaps for the last time. The uncertainties ahead consume their thoughts.

The troops understand the task ahead, Sicily is considered the best-fortified island in the Mediterranean, and they are assigned to breach its defenses at one of the strongest points. They know the assault will be tough, and many accept that some of them will not make it back. However, their rigorous training has given them confidence in their abilities, and they are determined to prove themselves against the enemy.

| The Plan |

The southern coast of the Maddalena Peninsula, located south of Syracuse in Sicily, is characterised by rugged, rocky terrain throughout its entire length. At the western end, near the area known as Terrauzza, there is a flat, rocky beach suitable for landing from the sea. In contrast, towards the eastern end, near Cape Murro di Porco, the cliffs rise steeply, reaching heights of 15 to 20 metres, often undercut at the base, making them appear nearly impossible to climb.

Between Cape Murro di Porco and the beach at Terrauzza, the cliffs alternate between sheer faces and sections where the rocks are near sea level. In these areas, the rocky ground rises in stepped layers or steep bluffs towards the central ridge of the peninsula. Today, remnants of a Second World War gun battery, named Lamba Doria after an Italian naval hero, can still be found among the rocky outcrops above the cliffs near the cape, approximately 200 to 300 metres from the cliff edge. This gun battery played a significant role in defending the Sicilian coast during the Allied invasion.

During the night of July 9th, 1943 and July 10th, 1943 the Special Raiding Squadron was tasked with climbing the cliffs of the Sicilian coast and to attack and destroy the Lamba Doria gun battery. The plan to land 800 metres west of the battery was likely devised for several reasons. The lower cliffs and increased distance from the battery provided a measure of safety, allowing the only road leading to the battery to be blocked before the main assault. This would also prevent Italian reinforcements from attacking the Special Raiding Squadron from the rear during the assault.

No. 3 Troop was meant to land at the westernmost point and move north to block the road and capture a farm called Masseria Damerio. Next to them, the mortar troop was intended to land and take positions inland, along the ridge’s crest. No. 2 Troop was to circle around the battery and attack from the north, while No. 1 Troop was tasked with a direct assault from the west. The careful distribution of troops was intended to ensure coordinated attacks from multiple directions while cutting off any Italian reinforcements. Other units are notified of the potential locations of the Special Raiding Squadron to prevent any incidents of friendly fire.

Upon completion of the assigned task, the squadron is instructed to either:

(a) Rejoin H.M.S. Ulster Monarch directly. Arrangements should be made to summon the landing craft to the selected beach or embarkation point.

(b) Move westwards to join the 5th Infantry Division, which will be advancing northwards from Beach 44 towards Syracuse.

Therefor they move towards the nearest flat beach, located at the base of the Maddalena Peninsula, near an area called Terrauzza. This site also provides the nearest road leading off the peninsula. From there, the Special Raiding Squadron can either re-embark on H.M.S. Ulster Monarch or proceed westwards towards the main highway, where they are likely to join up with the main force advancing northwards to capture Syracuse.

The method chosen is left to the discretion of the commanding officer based on the situation at the time, with the objective being to return the squadron to H.M.S. Ulster Monarch as soon as possible for reorganisation and preparation for further seaborne operations. If hostile batteries or defended positions are encountered during withdrawal, the squadron is authorised to engage and destroy them if it is within their capability.

| The Operation |

On July 9th, 1943, a ship-wide announcement pulls everyone back to reality. The navigator’s calm voice announces, “If you look out to starboard, you can see the summit of Mount Etna, Sicily’s highest mountain.” The sight of the volcano’s cone rising above the clouds brings home the realization that this is not an exercise, this is the real invasion.

By 16:00 hours, the sea becomes choppy. Earlier, the Mediterranean had been calm, but now the wind has risen, and the waves grow larger. Seasickness begins affecting some of the men. By nightfall, the wind is a full gale, and the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch and the troopship H.M.T. Dunera pitch violently. The prospect of boarding landing craft and heading for shore under these conditions adds to their unease.

As darkness falls, tension builds, they are just hours away from the invasion. The ship rolls, seasickness takes hold, but by 01:00, the ship slows, and they switch to invasion lighting. The atmosphere becomes eerie, lit by dim, pale lights. They gather in the mess, forcing down bacon and eggs with hot coffee to stave off nausea.

At 02:00 Hours, they prepare to embark. The order comes over the loudspeaker, and they head to their boat stations. Despite the nerves, the familiarity of the routine is reassuring. Through the open doors, they see the dark, rough sea. The sailors struggle to lower the boats due to the waves, and the men wait for what feels like an eternity.

Finally, the order to embark is given. The men move forward, helping one another into the landing craft. Weighed down by their gear and weakened by seasickness, it is a difficult process, but the sailors assist them. Suddenly, there is a splash and a shout of “Man overboard!” One of the soldiers has fallen in but is quickly rescued and returned to his boat. Lowering the craft into the sea is tricky, but thanks to the skill of the Landing Craft Assault crew, they manage it without incident and move away from the ship.

Once formed up, they begin the five-kilometre journey to shore, their landing site barely visible as a low, dark line. The sea remains rough, and waves and spray drench them. Many shiver, seasick and cold, using the cardboard buckets provided. After about thirty minutes, the sea becomes calmer as they approach the shelter of the shore, and some of the men recover slightly.

In the darkness, they approach the shore, nerves on edge. A searchlight sweeps the sea, raising concern, but the roar of engines and the crump of bombs reveal that their bombers are distracting the defenders. The searchlight swings skyward, chasing aircraft, and the men breathe a collective sigh of relief. They watch as bombs strike the target, while the anti-aircraft fire tries, and fails, to find the bombers.

The night is calm, with only the sound of waves as the landing craft move closer to the Sicilian shore. Suddenly, the silence is broken by a loud commotion nearby. Though still about 180 metres from the coast, the noise seems very close. In the dim light, approximately 20 metres away, they spot a low, dark shape with torches flashing and men shouting. Panic briefly sets in as they fear they have been discovered by an enemy E-boat. Their hearts pound, believing that their end is near in their defenceless state. However, relief quickly replaces fear as they realise the voices are shouting in English, and quite colourfully at that. They halt to investigate and discover that it is one of their own gliders that has crashed in the sea. One of the boats picks up the remaining survivors, a small and disheartening number, and they continue their slow and quiet journey towards the shore. Somehow, the noise from the glider crash has not alerted the enemy, and the men feel fortunate for their continued luck.

The landing craft bumps gently onto the shore, and they disembark, executing the landing drills they have practised many times before. After assembling on the beach, they move towards the cliffs ahead. However, these are not true cliffs, after a short climb of about 1.5 metres, the terrain gradually rises in rocky steps and boulders, allowing them to reach the top without difficulty. Once there, they wait, as trained, and quickly establish contact with Captain Harry Poat at No. 3 troop headquarters. He orders them to stay put while he contacts the rest of the unit. They lie low, waiting for further instructions.

Suddenly, a sharp whistle cuts through the air, followed by the dull thud of a mortar bomb. Saunders cries out in pain, and word spreads that he has been wounded. Concerned, they check on him, finding that a bomb fragment has cut his hand. Saunders insists on staying, he refuses any suggestion of being evacuated. Mortar bombs continue to fall, but they soon realise that these are from their own side. Alec McDonald, with his mortar section, must have arrived minutes earlier and immediately started engaging targets. His second round hits directly, igniting ammunition and dry grass, conveniently illuminating the entire area. The troops of the Special Raiding Squadron land approximately 800 metres east of the planned assault point, directly below the battery, in what was considered the most hazardous area. No. 1 Troop and No. 2 Troop, the main assault force, land southwest of the battery, while No. 3 Troop and the mortar troop land further west, where the landing is originally intended. The unplanned landing locations of No. 1 Troop and No. 2 Troop places them in danger from both the Italian defenders and friendly fire.

The pylon, meant to be on the southwest corner of the two troops, should have been almost out of sight to their right if they had landed correctly. As No. 1 Troop and No. 2 Troop end up much closer to the battery than planned, this results in significant confusion. They conclude they have touched down too far east, placing them directly below the battery. The lack of enemy resistance at such a critical spot further confirms their unplanned landing. To their left, the steady, slow bursts of a Bren gun can be heard, then silence returns, interrupted only by the intermittent thump of Alec Muirhead’s 3-Inch Mortar Section mortar fire. There is still no sign of the enemy until they hear a pitiful wailing, a sound like a small child crying for his mother. It is an Italian soldier, evidently struck by the realisation that enemy forces are now within 90 metres of him, and that the noise is not an isolated glider landing but part of a larger invasion.

For about ten minutes, they remain in position, listening to the distant sounds of battle but with no sign of Captain Poat’s No. 3 Troop. Unsure of his whereabouts, and feeling frustrated at being left behind, they decide to take matters into their own hands. Given their off-target landing, they doubt Captain Poat has stuck to the original plan, which involved detouring to the west to attack from the north. Confident in the lack of opposition, they decide to move directly towards the gun battery, now visible and illuminated by the mortar section.

Upon cresting a small rise, they encounter a long, low barbed-wire fence. Just ahead, they spot silhouettes of troops, which they recognise as friendly. Approaching them, they find it is Johnny Wiseman’s section from No.1 Troop. Realising the mix-up, they quickly climb over the wire, anxious about possible booby traps or hidden machine guns. The urgency causes an unfortunate mishap, with one soldier tearing his trousers on the wire, resulting in a rather drafty situation.

Once across, they find themselves alone again as Wiseman’s section disappears into the night. Moving in extended line across an exposed area, the first bursts of enemy fire begin. Red tracer rounds streak towards their objective, intensifying in volume. The answering green tracers from the enemy are sporadic and weak.

“Sir! I don’t think we should move any further unless you want us all killed,” Corporal Mitchell advises calmly. As an experienced veteran, he recognises the danger of the near-misses. The lieutenant, still inexperienced, hesitates but eventually agrees with Mitchell. They come across another wire obstacle, even more formidable, and wisely choose to take cover behind a low bank they find nearby. Taking up defensive positions, they prepare to provide support where needed and to block any potential enemy escape from the battery’s southern side.

Mortar fire ceases, and a storm of bullets passes overhead. The lieutenant silently thanks Corporal Mitchell for his advice; otherwise, they surely would have taken casualties. They have no doubt that the fire they hear is from their own side, confirmed by the occasional burst of a Mills bomb and the faint sound of English voices. The noise gradually dies down, and they see figures moving through the enemy positions, sporadically firing or throwing grenades into dark corners. Recognising the voice of Sergeant Chalky White, a sergeant from No.1 Troop, the lieutenant shouts the password.

“Desert Rats?” he calls. “Kill the Italians!” comes the prompt reply, and they climb over the wire into the gun position to join their comrades from No.1 Troop.

A quick survey reveals that Captain Bill Fraser, commander of No.1 Troop, has kept his earlier promise to Harry that he would not be content with just capturing the camp buildings and leaving the guns to No.2 Troop. Instead, No.1 Troop pressed straight on to take the battery. The change of plan came directly from Paddy Mayne, who, realising the enemy’s weakness, decided to seize the objective immediately, abandoning the original strategy.

As they arrive at the scene, they find No. 1 Troop busy clearing the area. In the pale dawn light, they see groups of Italians standing under guard, visibly shivering. Some of the men are gathered around an air raid shelter entrance, from which noises emanate. After repeated threats and some persuasive small arms fire, the occupants are coaxed out, clearly relieved to be alive. Some are wounded, and much to their surprise, women and children emerge as well. The sight of these civilians,shabby, dirty, and ingratiating, is a stark contrast to the tough, fanatical defenders they had expected.

In the midst of the activity stands Paddy Mayne, calm and evidently pleased with their success. They have taken this important position without losing a single man. Paddy inquires about Harry Poat and the rest of No. 2 Troop, and although it is uncomfortable to admit they do not know, Paddy seems unconcerned. He signals their success by firing three green Very lights, and Harry Poat’s group arrives ten minutes later, having stuck to the original plan of attacking from the north. The lieutenant and his section sit in one of the gun pits, resting and lighting cigarettes, finally able to relax.

With dawn breaking, the men grow more confident, and discussions begin about their unexpectedly easy success.

Mayne soon orders the troops to disperse and prepare the prisoners for transport. They need to move quickly before daylight fully arrives, allowing time to demolish the guns and signal their success to the fleet. The prisoners, already numbering over 200 within 45 minutes of landing, are gathered and marched down a nearby track. The Italians, now reduced to harmless captives, appear pitiful, dirty, diminutive men who had been bullies when in control but are now eager to please. Their reputation for treating prisoners cruelly does not sit well with the British troops, who remain cold towards their ingratiating behaviour.

With the prisoners moved, engineers set charges on the guns, and soon the area echoes with explosions as the artillery pieces are destroyed. Tony Andrews is tasked with sending the prearranged success signal to the fleet, three green rockets, but has some difficulty. The first two rockets topple over, scattering green sparks, and the third manages only a short spiral before falling back. Nonetheless, it appears sufficient for the ships offshore, as within minutes, the fleet begins steaming towards the shore. Watching the ships approach, the men feel a sense of pride, knowing their efforts have made this possible.

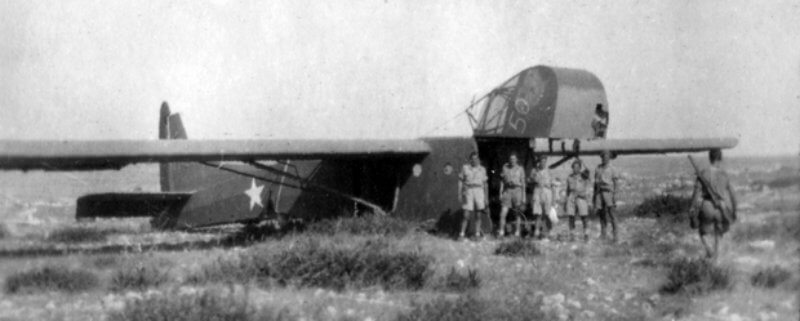

As the sun rises, they get a better view of the previous night’s events. They notice about a dozen small black patches floating on the water, gliders that had landed in the sea after being released too early. They estimate that at least twenty gliders went down in the water, possibly costing the lives of over three hundred men who never got the chance to fight. Turning their attention inland, they take in the rocky, shrub-dotted landscape. Among the stunted olive trees and dusty fields, they spot another glider wrecked against a stone wall, its back broken.

As they regroup, more glider survivors, including a brigadier, are brought in, shivering and disoriented. They attach themselves to Paddy’s headquarters, grateful to have been found. Soon after, the sound of approaching aircraft has the men diving for cover. A German Focke-Wulf 190 flies’ low overhead but passes without incident.

They take up a defensive position near the coastal track leading to the battery, wondering what Mayne’s next move will be. As they regroup at Masseria Damerio, a farm captured at the beginning of the operation. Suddenly, the sound of a distant gun makes them sit up. At first, they think it is artillery from their main forces inland, but then they see a plume of water rise near the fleet. An inland coastal battery has opened fire on their ships. Paddy immediately decides they must take out this new threat.

Initially, it appears that Mayne decides to return to the ship, as H.M.S. Ulster Monarch sends a signal to Corps Headquarters at 07:40 stating: “SRS moving by craft to UM.” This message suggests that the Special Raiding Squadron is already on board landing craft and heading back to the ship. Instead, the Special Raiding Squadron leaves Farm Damerio at approximately 06:00 hours and moves inland towards a tall farm building they can see in the distance.

This building turns out to be the observation post for the enemy battery. Most of the defenders have fled, and the few that remain are swiftly dealt with. Paddy establishes his headquarters there, and as the troops prepare to move on the battery, enemy fire ceases. The farm, is Casa Mallia, located near the highest point of the ridge. Here, the men taking a brief rest, with one receiving water from a local resident, while others are still wearing inflatable life-belts, suggesting that a sea journey remains a possibility. The farm at Casa Mallia provides a strategic view of the peninsula, including the location of battery AS 493, situated roughly 1.6 kilometres away, with its prominent rangefinder tower visible. They soon realise that the building is under fire from their own destroyers, mistaken for an enemy position. Fortunately, they have a forward observation officer who quickly calls off the bombardment.

The Mortar teams under Captain Muirhead begin bombarding the battery. The mortar bombardment achieves effective hits on the target. The assault on the battery takes on a relaxed, almost casual air. The troops move forward with confidence, often exposing themselves to draw enemy fire and locate their positions. There is little resistance, and the Italians either flee or surrender when the British approach. Despite the sporadic fire, the men chew on pieces of grass or snack on tomatoes from the fields, pressing on with their advance.

Eventually, they reach the battery to find it deserted. The officers’ mess still contains personal belongings, which are swiftly appropriated, and the magazine, rigged with explosives but left untriggered, is discovered. The enemy had fled in such haste that they had not completed their preparations to destroy the site. The battery at AS 493 is equipped with both anti-aircraft and anti-ship guns. The rangefinder is mounted on a high turret to maximise visibility, with a fire control centre positioned below. Captain Muirhead’s mortar teams, having been instrumental during the attack on Lamba Doria, now demonstrate similar effectiveness in engaging AS 493. Mortar fire begins at a range of 1,700 metres from near Casa Mallia, with bursts visibly landing on the target. The mortar team advances 250 metres closer, managing to score a direct hit on the rangefinder tower. They continue moving forward, firing from a position just 250 metres away, with rounds successfully striking the gun pits.

After the Italians discover that Lamba Doria has been overrun, The Crew of AS 493 returns to the battery and help to prepare for close-quarters defence. Despite efforts to respond, the battery suffers casualties, and the fire control centre takes multiple hits from mortar fire.

At the same time, Nos. 1 and 2 Troop attack. Even though they encounter strong resistance, they are able to capture the gun position comprising: five anti-aircraft guns (75 millimetres to 80 millimetres), one large rangefinder, four 4-inch mortars, and several machine guns. The guns are later identified as 102/35 anti-aircraft guns. The mention of 4-inch mortars is unusual, as gun batteries typically do not have such mortars. It is possible that the Special Raiding Squadron encountered a platoon of 81 millimetres mortars belonging to the Italian 385th Coastal Battalion, positioned nearby.

Following the capture of AS 493, the Special Raiding Squadron advances to two additional batteries guarding the entrance to Syracuse harbour. One of these, named Emanuele Russo, is captured by No. 1 Troop. They capture the gun position, including the battery commander and personnel. The final battery, numbered AS 309, consists of six 76 millimetres dual-purpose guns and is engaged by Muirhead’s mortars, which achieve significant results, including setting a cordite dump on fire and forcing the enemy headquarters to evacuate.

By midday, they settle into the shade of olive and walnut trees, resting while waiting for further orders. Their prisoners are tasked with gathering more tomatoes and walnuts, which are used to supplement their rations. Around mid-afternoon, they receive orders to return to squadron headquarters, where they regroup and learn they will be moving inland to link up with the main British forces.

Before setting off, the men share stories of the previous day’s events. The captured Italian troops number around 500, with another 200 enemy soldiers believed killed or seriously wounded. They have also rescued over fifty glider troops. Despite their success, one incident stands out, a prisoner who pretended to surrender before throwing a grenade, severely injuring a British soldier. Mayne had swiftly shot the Italian, ending the situation.

The prisoners seem eager to be captured. In one instance, they even helped a guard who had accidentally dropped his magazine. In another, Italians who had escaped capture earlier snuck back to join the prisoner column, preferring the certainty of captivity to the unknown dangers of freedom.

By early evening, they set off on their march inland. The formation is loose, as they believe all significant resistance has been dealt with. The route takes them past the second battery and through a valley lined with hedgerows. Suddenly, anti-aircraft fire erupts, and they stop to watch a dramatic scene unfold overhead. Twelve enemy bombers are intercepted by Spitfires, their tight formation scattered. They see several enemy planes shot down, their smoking wrecks spiralling to the ground.

Continuing their march, they come across the wreckage of more gliders and the body of a British soldier. Mayne leads the Special Raiding Squadron westwards, spending the night at a farm called Luogo Ulivo. This location is approximately 900 metres from the highway, where the Special Raiding Squadron is expected to link up with the main force. Fires are lit, sentries posted, and they eat a rough meal before bedding down in ditches with armfuls of straw. The cold bites through their thin blankets, making sleep elusive.

In the early hours, they are woken by another enemy air raid targeting the fleet. Anti-aircraft fire and the roar of engines fill the air as they watch from their ditches. As dawn breaks, they get up, eat a quick breakfast, and pull off ticks and other pests picked up during the night.

Marching again, they reach the main road and watch columns of British tanks rumbling inland—a heartening sight that signals the invasion’s progress. They settle in a field to rest, exploring a nearby farmhouse that turns out to have belonged to a Fascist, now abandoned. Chickens and turkeys are caught and roasted over open fires.

The Special Raiding Squadron joins the main force the following morning, on July 11th, 1943, nearly a day later than originally planned. On the morning of July 12th, 1943, they receive orders to return to the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch, now at Syracuse harbour. As they march towards the town, they see signs of the recent battle, ditches filled with discarded equipment and, occasionally, a decomposing corpse.

They cross a large bridge that had been the glider troops’ main objective. Only two gliders had landed near the target, and the men wonder what acts of heroism had occurred there during the fight for the bridge. They speak with the rescued glider troops, who are angry about their poor briefing and the inexperience of the American pilots, whom they blame for dropping them too far from the target. Whether true or not, it is clear that the glider operation had suffered from poor planning and inexperience, leading to heavy losses.

Reaching Syracuse just before 10:00 in the morning, they find the town in disarray, almost deserted, with shattered buildings and streets strewn with debris. They are taken aboard a ferry craft, fed, and transported out to the H.M.S. Ulster Monarch, anchored offshore with the rest of the fleet.

| Aftermath |

In 36 hours, they destroy 18 large guns, mortars, and machine guns, capturing over 500 prisoners and inflicting 200 casualties.

The Special Raiding Squadron loses Corporal Caton, with two others wounded. Their mission covers 40 kilometres in 18 hours, often outnumbered 50 to 1.

| Multimedia |