| Page Created |

| May 6th, 2022 |

| Last Updated |

| November 11th, 2023 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Additional Information |

| Special Air Service Order of Battle Commanders Operations Equipment Multimedia Sources |

| Badge |

|

| Motto |

| Who Dares Wins |

| Founded |

| July 1941 |

| Disbanded |

| October 8th, 1945 |

| Theater of Operations |

| North Africa * Egypt * Libya Mediterranean * Italy * Greece Western Europe * France * The Netherlands * Germany |

| Foundation |

You might consider the foundation of the Special Air Service (SAS) as one big coincidence. It all starts on May 20th, 1941, when the Germans perform the first coordinated parachute and glider attack on the island of Crete. This airborne assault makes the British realise that airborne troops can be used to land a large body of troops and equipment in hard-to-reach places to seize tactical objectives. Until then, the British focus on a more commando-like approach in the use of paratroopers. They decide to form two Parachute Brigades, one to be raised in Great Britain and the other in India. To facilitate the formation of the Parachute Brigade in India, Type X parachutes are shipped to the area.

However, fifty of these parachutes end up in Alexandria, in the hands of Jock Lewes, a member of No. 8 Commando. This commando is part of the Commando Brigade known as “Layforce,” under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Laycock. Layforce consists of No. 7 Commando, No. 9 Commando, No. 11 Commando, and the Special Boat Section of No. 8 Commando. The Brigade is created to support troops in North Africa with special operations. Unfortunately, General Headquarters Middle East lacks the ships to support any seaborne assaults of the Brigade.

Major-General Sir Robert Edward Laycock, Chief of Combined Operations in 1943

Another young officer from No. 8 Commando, known now as David Stirling, like Jock Lewes, is also playing with the idea of airborne insertions instead of seaborne. So when Jock Lewes comes up with the misplaced parachutes and has permission from Lieutenant-Colonel Laycock to start experimenting with them, Stirling is among the first to enter the program. In June 1941, a total of eight men from No. 8 Commando start parachute training at Mersa Matruh Airfield in Egypt. Lewes also gets hold of an old Valencia bomber. The biggest problem the group faces is that there is no parachute training center in the Middle East and none of them are parachute trained or qualified. Accidents are therefore waiting to happen. Unfortunately, the Vickers Type 264 Valentia they use has been converted to a mail plane. The aircraft lacks the proper rigging for fixed line parachutes. Undeterred, they tie them to the seats instead and jump anyway. For the first few jumpers, things go well, but Stirling’s parachute snags on the tailfin of the plane. This sends him plummeting to earth significantly faster than intended. Not much later, David Stirling is lying in the Scottish Military Hospital in Alexandria with temporary paralysis of both legs due to a spine injury.

Major Archibald David Stirling, founder and first Commander of the Special Air Service

During his time in the hospital, Stirling works on a paper in which he envisions a small raiding unit. This unit would consist of patrols of four men, with a total of no more than sixty men. They would land behind enemy lines by parachute, close to the target, hide until nightfall, then attack and retreat to a rendezvous area. There, they would be picked up by a transportation unit and returned to Allied lines. The significant advantage of parachute insertions over seaborne landings is that targets are not limited to coastal areas. Moreover, there’s no need to secure a beachhead and leave up to 25 to 30 percent of the troops behind. Thus, a larger force is needed than is necessary to reach the objective, which could compromise the element of surprise.

In July 1941, Stirling is released from the hospital. Convinced that the unit he envisions will be successful, he tries to sell his plan to General Headquarters Middle East. One story tells that Stirling, still on crutches, climbs the wall of GHQ Middle East to gain entry. After some effort, Stirling manages to contact the Deputy Commander of the Middle East, General Ritchie. Ritchie likes the idea and brings Stirling into contact with the new Commander in Charge of the Middle East, General Auchinlek. Auchinlek almost immediately takes to the idea, under pressure from Winston Churchill to mount commando-like offensive operations. With no ships available for Layforce and the Commando Force in North Africa diminished by action in North Africa and Crete, Stirling’s unit appears to be Auchinlek’s best bet. General Auchinlek authorises Stirling to draw a group of sixty-six men from Layforce to form his unit. This unit becomes known as L Detachment, suggesting that the parachute capability in North Africa is much larger than it actually is. It is attached to the Special Air Service Brigade.

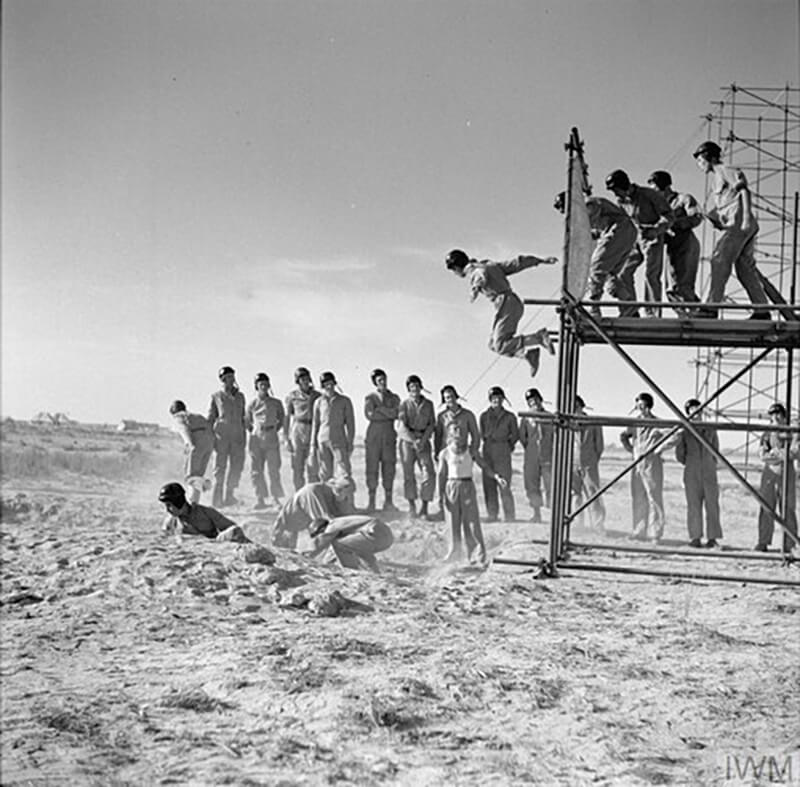

L Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade jumping from steel gantries while undergoing parachute training at Kabrit, Egypt in July 1941.

Within a week, six officers, five non-commissioned officers, and fifty-five enlisted men are selected to form the nucleus of the unit. The training area is set up in Kabrit, at a small airport on the edge of the al-Buḥayrah al-Murra al-Kubrā (Great Bitter Lake). The training facilities at Kabrit are quite basic, but a nightly “shopping trip” to a nearby New Zealand army camp makes things more comfortable. Training includes improvised parachute training, navigation skills, desert survival, and combat. The parachute training proves particularly hazardous, as the unit cannot draw from the experiences at Ringway.

Their trainers are sourced from No.1 Parachute Training School (P.T.S.), formerly the Central Landing School, an RAF-operated facility in Ringway and Tatton Park, Manchester. This center has been active in parachute training since June 1940.

The dispatch of these instructors to the detachment comes after prolonged communications with Middle East Headquarters (M.E.H.Q.), instigated by a request from Stirling himself. Eventually, approval is granted, and the trainers are transported via the WS 10 convoy, boarding the R.M.S. Windsor Castle and arriving at Suez in September 1941. There, they begin their assignments after a period of acclimatisation.

At Kabrit, the new arrivals, Flight Sergeant Jim ‘Ginger’ Averis, Sergeants ‘Natch’ Markwell, Ian ‘Mac’ McGregor, and Ken ‘Joe’ Welch, quickly become known as ‘The Four Toffs.’ This nickname results from their high-stakes games of poker and boxing during the voyage, which net them a stash of luxuries like quality cigarettes and other coveted items. Their living conditions are a far cry from what they have known back at Ringway, with only tents for shelter and a directive to make do as best they can. They are quickly assimilated into the fold under the guidance of Pat Riley, who ensures that they integrate smoothly with the troops.

Their training methods include some innovative techniques, likely inspired by Len Willmott, an S.O.E. signaller who has experienced similar training. The instructors begin in earnest once parachutes and aircraft are at hand, initially using the limited resources they bring with them to teach proper parachute packing techniques to avoid malfunctions like the dreaded ‘roman candle.’

They take a hands-on approach, building a twelve-foot tower to drill the men in the art of jumping and landing correctly. This rigorous regime results in a significant improvement in training quality, transforming the camp into what would be recognised as No. 4 Middle East Training School, a hub that sees forty-seven courses through by the summer of 1943.

The trainingis is not without casualties. During parachute training, two men die when their static line fails as they drop from a Bristol Bombay Bomber. The “graduation” assignment is, besides testing the unit’s capabilities, also intended to silence the critics of the unit.

During the exercise, forty men of the unit move 140 kilometres through the desert on different routes towards Heliopolis, the main Royal Air Force base near Cairo. They slip in unnoticed, stick tape on the aircraft, and slip out undiscovered. In the months to follow, the unit prepares itself for their first assignment. A parachute assault on five German airfields to support General Auchinlek’s November offensive. They gather intelligence, study maps, work on their assault plan, and prepare their equipment. Jock Lewes produces the Lewes bomb, a time-delayed bomb to destroy aircraft. L Detachment is ready for their first assignment. Despite some reservations and the tragic loss of two men, the instructors’ steadfastness brings the others up to a commendable level of proficiency.

Men from L Detachment emplaning into an RAF Bristol Bombay transport aircraft prior to a practice jump while undergoing parachute training at Kabrit, Egypt in July 1941.

| Into Battle |

On November 15, 1941, the assault force, along with their charges, heads to the forward landing ground at Maaten Bagush, ready for Operation Squatter. All four instructors participate, with an Australian, John Pott, as the fifth dispatcher. Joe Welch’s concerns about the upcoming conditions are dismissed, and the operation proceeds, with Welch dispatching Stirling’s section, Pott with Bonington’s section, and McGregor, Averis, and Markwell joining Mayne, McGonigal, and Lewes.

Operation Squatter, starting on the night of November 16th/17th, 1941, is a testament to the courage of the men who jump into the maelstrom, their training, instruction, and the knowledge they receive from their instructors. Of the four sections that jump, only six out of the forty-od

| Special Air Service Regiment |

In September 1942, General McCreery, Chief of Staff to General Harold Alexander, Commander-in-Chief of Middle East Command, writes to his superior regarding a small special forces unit active in North Africa. He praises the unit for its notable past successes and high morale, attributing much of this to the leadership of the current commander of L Detachment Special Air Service Brigade. McCreery suggests that L Detachment Special Air Service Brigade, the 1st Special Service Regiment, and the Special Boat Section be amalgamated under the command of Major D. Stirling, recommending his promotion to lieutenant-colonel.

General Alexander agrees with this proposal, and on September 28th, 1942, General Headquarters Middle East Forces issues an order promoting David Stirling to Lieutenant-Colonel, authorising him to expand his unit into a regiment. Stirling plans for the Special Air Service regiment to consist of five squadrons, A, B, C, D, and Headquarters. D Squadron being the former members of No. 1 Special Boat Section. The unit has a total establishment of 29 officers and 572 other ranks. He is immediately faced with the challenge of filling his expanding regiment with suitable personnel while also contributing to the Eighth Army’s upcoming offensive against Axis forces at El Alamein.

Stirling assigns his most experienced men from L Detachment to form A Squadron, led by the formidable Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne. Their mission is to launch attacks on targets along the coast between Tobruk and the rear of the enemy front line. As A Squadron ventures into the desert to confront the Germans, Stirling heads back to the Special Air Service base at Kabrit, situated about 145 kilometres east of Cairo, to carry on with recruitment and oversee the training of the new soldiers. He has to create his regiment from the units assigned to his new command.

First of all, there is, L Detachment, Special Sir Service Brigade. It transforms into the 1st Special Air Service Regiment in October 1942. It aims to comprise five squadrons with about 50 officers and 450 other ranks. At that time, the regiment hasn’t achieved full strength, having approximately 40 officers and 350 other ranks. Stirling plans to supplement these numbers with members from the Middle East Commando. When Stirling takes command of the Middle East Commando around November 1942, he finds the unit to be of good quality but underutilised and poorly led. Initially consisting of about 30 officers and 300 other ranks, Stirling’s plan is to disband the majority of the unit, retaining only 10 officers and 100 other ranks to bring the 1st Special Air Service Regiment up to its intended strength.

The French unit under his command is by January 1943, transformed into a French Special Air Service Squadron, expanded to roughly 14 officers and 80 other ranks. Stirling envisions this squadron as the core of a prospective French Special Air Service Regiment, envisaged to conduct operations in France in anticipation of, and during, the expected Second Front in Europe.

Besides the French towards the end of 1942, Stirling has assumed command of the Greek Sacred Company. His intention is to deploy the Greek Sacred Squadron for raiding operations in the Eastern Mediterranean, where their local expertise would be highly valuable.

Operating independently until August 1942, No. 1 Special Boat Section is known for numerous successful missions, Stirling’s intention is to incorporate them into the 1st Special Air Service Regiment as D Squadron, providing them with comprehensive Special Air Service training, including parachuting, in the meantime. They comprise about 15 officers and 40 other ranks.

One marginal unit under Stirling’s command Captain Buck’s Special Interrogation Group, ceases to exist due to recruitment challenges and casualties.

In January 1943, David Stirling instructs Sutherland of D Squadron to lead a detachment of 50 men to Beirut to train in seamanship and guerrilla warfare tactics. Initially, Sutherland resists, eager to join the Special Air Service in pushing the Germans out of North Africa. Stirling’s response is immediate and emphatic, highlighting the invaluable small boat operational experience possessed by the Special Boat Section.

Sutherland arrives in Beirut on the early morning of January 20th, 1943. Four days post Sutherland’s arrival, Stirling is captured, which precipitates Sutherland’s return to Kabrit. With Stirling captured, the Special Air Service finds itself without clear direction or leadership. Paddy Mayne, who is Stirling’s nominal successor, has an even more profound disdain for bureaucracy than Stirling, leaving the complex administrative tasks at Kabrit to the regiment’s adjutant, Captain Bill Blyth. Blyth now sits, surrounded by piles of files, facing the administrative challenges head-on, symbolising the Special Air Service’s momentary state of limbo.

Despite Stirling’s absence, Middle East Headquarters is actively deliberating over the future role of the Special Air Service. The Desert War is on the brink of conclusion, significantly reducing the need for the Special Air Service’s renowned hit-and-run raids as Axis forces retreat from North Africa. This situation leads Middle East Headquarters to consider how to effectively utilise the unique skill set of the Special Air Service moving forward.

The resolution involves disbanding the regiment. The French Squadron is sent back to Great Britain to form two separate regiments. The Greek Sacred Company heads to Palestine to start gearing up for operations in the Mediterranean. In April 1943 four out of the five Special Air Service squadrons are merged to establish the Special Raiding Squadron under Paddy Mayne. The leftover D Squadron, a blend of new recruits and seasoned members from what Stirling had dubbed the ‘Folboat Section’, is rebranded as the Special Boat Squadron (SBS), under the leadership of Captain the Earl George Jellicoe. This restructuring signifies a crucial transition in the Special Air Service’s organization and strategic orientation, aligning with the evolving demands of the conflict.

| 2 Special Air Service |

From late 1942, it becomes clear that Lieutenant Colonel Bill Stirling, Comanding Officer of the Small Scale Raiding force (SSRF) and others are considering moving part or all of the Small Scale Raiding Force to North Africa. The Small Scale Raiding Force also knwown as No. 62 Commando, was formed in 1941, consists of a small group of 55 commando-trained personnel working under the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Under the operational control of Combined Operations Headquarters, No. 62 Commando is commanded by Major Gustavus Henry March-Phillipps.

The Small Scale Raiding Force carries out a number of cross-channel operations with mixed fortunes. Operation Barricade and Operation Dryad are complete successes. However, during Operation Aquatint on the night of September 13th, 1942, at Sainte-Honorine on the coast of Normandy results in the loss of all involved, including Major Gustavus Henry March-Phillipps. Following the loss of March-Phillipps, Captain Geoffrey Appleyard is given command of the Small Scale Raiding Force. After a few more succesful raids the unit is expended and Lieutenant Colonel Bill Stirling. Bill Stirling is the older brother of David Stirling.

With the prospect of the upcoming invasion in Northern Europe raiding becomes less and less attractive in the area, the Mediterranean’s relative calm offers better prospects for sea raiding than the British Channel. The frustrations of operating the Small Scale Raiding Force in domestic waters around Britain are well documented in previous chapters. With the United States involved in the war, the North African campaign is under joint Allied command. The idea of invading Vichy French North Africa has been discussed throughout 1942, and in July 1942, a decision is made for an autumn invasion, led by American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, named Operation Torch.

Simultaneously, Special Operations Executive begins negotiations in August to establish an advanced, self-supporting base in North Africa to support both Operation Torch and the planned Allied invasion of Europe. By November, arrangements are in place for Special Operations Executiveo open its North African base under the codename Massingham Mission.

Operation Torch commences in early November 1942, with seaborne landings at Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers. The Allied forces fight eastward into Tunisia. On November 17th, 1942, the advance party for Brandon Mission arrives and sets up a base at Cap Matifou, near Algiers. Brandon Mission, under Lieutenant Colonel Young, assists Operation Torch with special detachments behind enemy lines in Tunisia, employing many Free French agents. Major Gwynne joins Brandon Mission in February 1943.

However, in December 1942, U.S. Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson, commanding the British and American forces in Algiers, is disappointed with Brandon Mission’s work. This Special Operations Executive Mission in Algiers was responsible for organising special operations in the First Army area in Tunisia. It is set up under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Young in November 1942. On December 18th, 1942, Anderson requests Colonel Bill Stirling of the Small Scale Raiding Force and some of his detachment be sent to him. The British High Command consents and indicates that the Small Scale Raiding Force should receive reinforcement from the commandos. The Operations and Training Director of the Special Operations Executive is Brigadier Colin McVean Gubbins, code name M. M visits Massingham Mission in early 1943, staying for nearly six weeks in preparation for the expected European invasion. He initially agrees to the American request.

Special Operations Executive’s Lieutenant Colonel Young, commanding Brandon Mission, is displeased with Anderson’s criticisms and the request for a fresh unit. It is unclear how Anderson learns of and requests the men from Anderson Manor. Bill Stirling and Geoffrey Appleyard’s enthusiasm to go to North Africa likely contributes to Anderson’s request. By January, the impending loss of MTB 344 and difficulties in finding suitable targets in the Channel fuel Stirling’s wish for a more profitable war zone.

Bill Stirling spreads the word that the Small Scale Raiding Force might be more productive in North Africa, which reaches Lieutenant General Anderson, possibly through Stirling’s brother, David. M had previously shared control of the Small Scale Raiding Force with Mountbatten’s Combined Operations and is reluctant to loan Small Scale Raiding Force men to Anderson, not wanting to lose experienced agents like Appleyard and Lassen. However, since Massingham and Brandon are SOE missions, attaching the Small Scale Raiding Force to them allows M to retain overall control.

On January 16th, 1942, British General Alexander meets Eisenhower and Lord Mountbatten to agree on creating a new force similar to David Stirling’s 1 Special Air Service. Initially, this force is to consist of 200 commandos under Eisenhower’s command. The Small Scale Raiding Force men, with their special skills, are an obvious choice. Mountbatten announces the agreement on January 20th, 1943, to Major General Haydon in London. Concerns arise about Bill Stirling leading the new force due to potential conflicts with David Stirling and Lord Lovatt.

Generals Alexander and Eisenhower, eager to increase long-range sabotage raids and amphibious operations, seek a detachment of the Small Scale Raiding Force. The Small Scale Raiding Force is asked on January 20th, 1943, to provide two officers to train and participate in operations with David Stirling’s men. Despite Major General Haydon’s firm opposition, the decision is made to send 50 British commandos, including half of the Small Scale Raiding Forcemen at Anderson Manor, to North Africa. Bill Stirling is determined to command the force, and David Stirling’s capture in January 1943 removes objections about potential personality clashes.

Two Small Scale Raiding Force officers, Philip Pinckney and Anders Lassen, are sent as the advance guard to Cairo in early February 1943, formally attaching to 1 SAS under Major V. W. Street. Bill Stirling travels by air shortly afterward, along with either his Administrative Officer, Captain Barkworth, or Patrick Dudgeon. Geoffrey Appleyard, the Operational Commander of the Small Scale Raiding Force, brings the main body of men and equipment by sea, divided into two parties. Peter Kemp assumes operational command of the remaining Small Scale Raiding Force men at Anderson Manor.

The Massingham Mission war diary for February 1943 shows SOE’s misgivings about the Small Scale Raiding Force’s impending arrival. Initially, London understands that the Small Scale Raiding Force will be under Eisenhower’s orders, but this position changes. M, present at Massingham in February, learns that Allied Force Headquarters (AFH) in North Africa is less anxious to have the SSRF, foreseeing limited scope due to a shortage of sea transport. Allied Force Headquarters suggests using the Small Scale Raiding Force as commando reinforcements, which M opposes.

Despite orders to reconsider, Appleyard departs England before any counter-orders arrive. By February 17th, 1943, Massingham Mission is informed that Appleyard’s party has left the Great Britain by sea, followed by the rest of the Small Scale Raiding Force detachment on February 19th, 1943. M’s control over his agents’ movements is less effective with his absence from England, and both Stirling and Appleyard are keen to join the “real war” in North Africa.

On February 19th, 1943, M receives a message indicating Appleyard’s departure may impact the Small Scale Raiding Force’s leadership in England. Horning, suggested as the new planning role at Anderson Manor, lacks navigational experience. M decides to instruct Stirling to send Appleyard back to England after handing over his party, replacing him with Horning. Appleyard’s return to Anderson Manor will ensure the Small Scale Raiding Force’s future as a unit there.

By mid-February 1943, Major Geoffrey Appleyard of the Small Scale Raiding Force travels by ship to North Africa with the first contingent of the unit from Anderson Manor in Great Britain. Captain Roy Bridgeman-Evans, whom Appleyard interviewed and recruited after Gus March-Phillipps’ death, serves as his second-in-command during the voyage.

The Small Scale Raiding Force arrives in North Africa to find confusion. 1 Special Air Service is in flux after David Stirling’s capture, and there is no immediate work for the Small Scale Raiding Force. M orders Bill Stirling to send Appleyard back to England, but a power struggle ensues. M departs for England on March 7.

Massingham Mission becomes hostile to the Small Scale Raiding Force’s arrival. Bill Stirling is disillusioned by the situation, partly due to Combined Operations’ enthusiasm to deploy the Small Scale Raiding Force despite no appropriate work. Allied Force Headquarters threatens to send the Small Scale Raiding Force to Army Group Headquarters for general operational duty, exactly what M feared. Coordination issues arise with Brandon Mission over personnel and operations.

Eventually, it is decided that Stirling’s command will include the Small Scale Raiding Force men who traveled with him and a small detachment of 1 Special Air Service. For veterans like Appleyard and Lassen, the situation resembles their arrival in West Africa with the Maid Honor Force, initially kept idle by local commanders.

On March 16th, 1943, M asks if Appleyard has left for home. Despite direct orders, Appleyard remains in North Africa. A power struggle continues, with Appleyard caught between commanders. By April 23rd, 1943, Combined Operations asks for Appleyard’s immediate return, but this is deferred to mid-May. London loses the power struggle, and Appleyard remains in North Africa for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

After David Stirling’s capture, 1 Special Air Service reorganises into the Special Boat Squadron (SBS) under Lord Jellicoe and the Special Raiding Squadron (SRS) under Paddy Mayne. Pinckney and Lassen join the SBS. Bill Stirling sets up 2 Special Air Service, taking Appleyard and Dudgeon, although Appleyard remains officially under SOE. Stirling aims to run 2 Special Air Service similarly to his brother’s 1 Special Air Service.

Major Appleyard does not appear troubled by the competition for his and the Small Scale Raiding Force’s services. He enjoys a peaceful voyage, undisturbed by enemy action, and arrives in North Africa by late February or early March. He describes the force as 1 Small Scale Raiding Force, the title given to the men of No. 62 Commando at Anderson Manor after its expansion following March-Phillipps’ death. Appleyard is keen to keep the force together, even if it means temporarily detaching from M’s command.

In North Africa, 1 Small Scale Raiding Force settles near Philippeville in Algeria, initially staying intact. By April 19th, 1943, Cochrane is still writing home using the 1 Small Scale Raiding Force address. Appleyard praises the camp in a letter home: “A delightful place, right on the sea amongst sand dunes about ten miles from the nearest town. A healthy spot with excellent training areas, wonderful surfing, and great fun with the boats.”

As weeks pass, special forces in North Africa reorganize. Under Bill Stirling’s plans, 1 Small Scale Raiding Force becomes part of the new 2 Special Air Service, with Philippeville remaining their base. Despite its beauty, Philippeville hides a deadly malarial swamp, which hampers 2 Special Air Service operations in 1943 and 1944. Appleyard’s earlier assessment of a “really healthy spot” proves wrong, as Major Roy Farran describes: “The undergrowth hid a dangerous malarial swamp.”

Initially, the dangers of malaria are not appreciated, and Appleyard and 1 Small Scale Raiding Force/2 Special Air Service experience a time of optimism. Appleyard writes home about their prospects and the potential for significant contributions: “Prospects are good, and we’ll be busy soon. We can do a useful job here, and there’s much cooperation and keenness.”

In March, Appleyard begins rigorous training for his men in local conditions, including marches across the African countryside with heavy packs. Bridgeman-Evans is impressed by Appleyard’s meticulous planning, recalling: “He taught me how to plan operations with detailed precision. Every exercise was planned and executed as an operation.”

Between March and July, Appleyard and the men of the 1 Small Scale Raiding Force gradually integrate into 2 Special Air Service. By June 25th, 1943, Appleyard commands A Squadron of 2 Special Air Service, with 12 officers and 156 men, under Bill Stirling. As Operations Officer, Appleyard oversees all regimental operations. All ranks are parachute trained, but I’m more interested in other entry methods where my experience lies. George Jellicoe is with us, and he’s one of the best.”

It is difficult to pinpoint the last operation by the 1 Small Scale Raiding Force and the first by 2 Special Air Service. However, Special Operations Executive records show Appleyard remains on their books until July 1st, 1943, with plans to return to Secret Service duties.

Appleyard remains busy with planning and executing operations from his arrival in North Africa. Whether under the 1 Small Scale Raiding Force or 2 Special Air Service, his operations continue the character developed during the Small Scale Raiding Force days at Anderson Manor.

| Northern European Invasion Preperations |

In mid-1943, the Chief Of Staff to Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC) proposes a concept of operations for the Special Air Service during the invasion. They envision the SAS as a self-sufficient unit capable of deploying mobile detachments by land, sea, or air to conduct prolonged offensive operations behind enemy lines, 80 to 480 kilometers from the beaches, likely in conjunction with local resistance forces. However, there are no concrete plans for the command, control, organizational, and logistical needs of the Special Air Service Brigade, nor for a sponsoring higher formation. As a hostilities-only creation from the Middle East, it lacks a permanent home.

On December 6th, 1943, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) considers bidding for the brigade but is already stretched thin with operations like Jedburgh, Bardsea, and Dunstable, along with activities in Norway and France. Its fragile logistical infrastructure cannot support a motorized, multinational brigade involving amphibious and airborne warfare. The Director of Military Operations decides in December 1943 that the brigade should be integrated into an army structure, supporting the 21st Army Group rather than being part of any secret service. The Chiefs of Staff committee reject the Special Operations Executive’s bid, much to the satisfaction of various Army factions vying for control of the Special Air Service.

Several military bodies tender bids for the brigade, including the Directorate of Combined Operations, facing an uncertain future after Admiral Lord Mountbatten’s departure to Southeast Asia. The British, Canadian, and Polish-manned 21st Army Group, commanded by General Sir Bernard Paget, also bids for control. As this group is one of two Army Groups (the other composed of American and French formations), and the Special Air Service Brigade is to support both, their bid is not considered. COSSAC, still a planning group and not yet transformed into the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), is also interested but lacks the necessary administrative machinery and mandate for raising a new, multinational formation.

In late December 1943, Generals Morgan and some of the British staff align themselves with General Paget and the 21st Army Group, a purely Anglo-Canadian formation. However, they receive a shock when General Montgomery is appointed Commander-in-Chief of the 21st Army Group and Land Force Commander for the invasion phase of Overlord, bringing General Freddy de Guingand as Chief of Staff. General Paget is reassigned to Cairo as Commander-in-Chief, Middle East Forces, under General Henry Wilson, Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean Theatre. General Morgan becomes Deputy Chief of Staff, SHAEF, working loyally under General Bedell Smith, the American Chief of Staff.

In summer 1943, Headquarters Airborne Forces, initially subordinate to the War Office and not part of the 21st Army Group, becomes technically subordinate to the 21st Army Group by December. Airborne Forces have a sound administrative structure and recent, albeit limited, experience in commanding Special Forces, having temporarily placed elements of the Special Raiding Squadron (SRS) and 2 Special Air Service under the 1st Airborne Division in southern Italy. This integration is instigated by General Frederick Arthur Montague ‘Boy’ Browning, an advisor to the Commander-in-Chief, Allied Forces Mediterranean, General Eisenhower.

General Browning, eager for active command, envisions the Special Air Service as part of an Allied Airborne Army that would descend into Europe ahead of an invasion force. In Italy, Browning rationalizes aircraft sorties and equipment use, especially parachutes. Despite some suspicion that Airborne Forces want to assimilate any parachute or glider-capable formation, there is harmony on a personal level between Special Forces and airborne units during preparations for Overlord. Lieutenant Colonel Ian Collins, a world-class tennis player and publisher, becomes GSO2 (Special Air Service) at Headquarters Airborne Forces, significantly aiding the Special Air Service’s establishment in north-west Europe.

COSSAC Study Paper No. 6, issued on 28 December 1943, outlines Special Air Service operations in enemy rear areas before, during, and immediately after D-Day. The Special Air Service is tasked with harassing enemy formations, supporting resistance forces, and conducting strategic operations during the breakout and advance into Germany. However, the paper is simplistic and naive, prepared by staff officers with little experience in Special Forces operations. It receives review and revision when experienced Special Air Service officers arrive in Britain.

The Special Air Service Brigade’s formation involves headquarters and four to six regiments, with a base near Perth, Scotland, offering ideal training and operational facilities. The French Demi-Brigade, comprising the 3rd and 4th Bataillons d’Infanterie de l’Air, integrates into the new formation. On December 6th, 1943, it commences moving to the Perth area, with the Etats-Major (HQ) and 3 Bataillon d’Infanterie de l’Air to Comrie, and 4 Bataillon d’Infanterie de l’Air to Largo, soon to become 3 and 4 SAS. In late 1943, the War Office requests training assistance from Allied Forces Headquarters, Algiers, leading to the establishment of an Special Air Service Training Centre at Baltilly Camp, Ceres, near Largo.

In late 1943, there is a proposal for the Special Air Service Brigade Order of Battle to include five or six operational squadrons, including an American unit. This idea is thought to have come from Special Operations Executive/Office of Strategic Services and comprised the NORSOG, French, and US Marine Corps operations groups, augmented by volunteers from the 1st Ranger Battalion and parachute and glider units.

A directive from June 1944, includes 6 (US) SAS Regiment as part of the brigade. However, due to the long-held U.S. antipathy to having their personnel commanded by foreigners, the proposal disappears as the Americans refuse to accept the primacy of Special Operations Executive in directing clandestine warfare on the continent.

Despite initial plans to base the brigade in Perth, complications related to Operation Fortitude North and SIGINT breaches prompt a change to Ayrshire. The area offers excellent training facilities and accommodations for the brigade, which begins relocating in February 1944. The bureaucratic struggle to secure the return of Special Air Service units from the Mediterranean theatre further delays preparations. The new Special Air Service formation has just over 100 days to prepare for D-Day, with training and recruitment challenges to address.

On September 28th, 1943, the War Office requests Allied Forces Headquarters to release Special Air Service units in the Mediterranean for Overlord. Allied Forces Headquarters replies on September 30th, 1943, indicating a need to retain some Special Air Service for operations in the Aegean. On October 13th, 1943, Allied Forces Headquarters agrees to release 2 SAS, less one squadron, for Great Britain. Further signals and delays ensue, with Allied Forces Headquarters clarifying on October 19th, 1943, that 1 SAS should return to the Middle East while retaining one squadron of 2 SAS in Italy.

On November 16th, 1943, General Headquarters Middle East requests to retain all of 2 SAS for Aegean operations. The War Office insists on 2 SAS’s return for Overlord preparations. After further exchanges, Allied Force Headquarters agrees on December 17th, 1943, to dispatch 2 SAS with convoy MKF 27. By December 20th, 1943, the War Office demands immediate clarification and finalizes the return arrangements.

On January 26th, 1944, Winston Churchill intervenes, ensuring the return of 2 SAS for Operation Overlord. The Chiefs of Staff follow up on January 30th, 1944, questioning the availability of special service troops in the Mediterranean. On January 31st, 1943, General Wilson insists on retaining 2 SAS but is overruled by Churchill on February 14th, 1943.

The final arrangements see 2 SAS departing Algeria on February 23rd, 1944, with convoy MKF 29. Despite continued requests to retain a squadron in Italy, 2 SAS returns to Great Britain in time to prepare for Operation Overlord. This bureaucratic struggle leaves the Special Air Service Brigade with just over 100 days for final preparations, significantly impacting their readiness for D-Day.

| Special Air Service Brigade |

The initial plan for the Special Air Service formation envisions a brigade headquarters and four to six regiments. Brigade Headquarters divides into five elements: Tactical Headquarters, Rear Headquarters, Administrative Base, Special Air Service Training and Reinforcement Camp, and 20 Liaison Headquarters. Each regiment, theoretically, comprises a headquarters, a headquarters squadron, and four operational squadrons. The French also have an additional company, later designated as a squadron, known as the Compagnie/Escadrille Leger. Two regiments are British and Commonwealth, two are French, and the others are manned by Allied troops.

The French Regiments are under the command of the Etats Major d’Infanterie de l’Air (EMIA), the headquarters for all Free French airborne forces. This unit is initially non-operational. In early 1944, it relocates from Camberley to Sorn Castle, sharing space with the Special Air Service Brigade Headquarters. This move increases its responsibility for non-Special Air Service and non-British based Free French airborne formations. In the winter of 1943-44, twelve Etats Major d’Infanterie de l’Air personnel attend parachute courses at No. 1 Parachute Ttraining School, fostering comradeship and creating a small reserve pool. When regiments move south for Operation Overlord, the Etats Major d’Infanterie de l’Air splits. Most of the staff heads south to stay close to the Special Air Service and Special Forces Headquarters. A rear-echelon remains in Ayrshire before moving south with the rest of the Special Air Service Brigade. At one point, an Etats Major d’Infanterie de l’Air element is considered for deployment with Tactical Special Air Service of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), 21st Army Group, or 9th Army Group but remains in London due to lack of operational equipment.

20 Liaison Headquarters, a team of twelve French or French-speaking British officers and other ranks, is led by Lieutenant Colonel Oswald Cary-Elwes, a pre-war officer in the Lincolnshire Regiment. The team’s role involves handling inter-Allied liaison, especially over supply and administrative matters between the British military, civil authorities, and the Etats Major d’Infanterie de l’Air, Demi-Brigade Headquarters, and individual French Special Air Service Regiments. Lieutenant Colonel Cary-Elwes, fluent in colloquial French from his schooling in France, joins the British Army in the 1930’s and is appointed Brigade Major of a Nigerian brigade after Dunkirk. His main role as Officer Commanding 20 Liaison Headquarters is to act as a liaison between the French and Belgian regiments and the British military, civil, and sometimes ecclesiastical authorities.

The Special Air Service Brigade officially forms on February 8th, 1944. Brigade Headquarters is set up in Sorn Castle, Ayrshire, described as a “spacious, commodious, and comfortable mansion.” Brigadier Roderick William McLeod, of the Royal Horse Artillery, commands the brigade. McLeod, experienced in active service on the North-West Frontier Province of India, Algeria, and Sicily, is unfamiliar with Special Forces tactics and requirements but does not shirk responsibility. He faces challenges, including the unpopular decision to order 1 SAS veterans to wear red berets instead of sand-colored ones, a decision made above his rank due to manufacturing difficulties during wartime. Despite bureaucratic issues, McLeod supports Lieutenant Colonel Robert Blair Mayne, ensuring the establishment of a new 1 SAS regiment within the Special Air Service Brigade.

The French Demi-Brigade with the two Bataillons d’Infanterie de l’Air relocates to Ayrshire by mid-February 1944, occupying billets in hutted camps near Cumnock and Auchinleck. The accommodation is deemed satisfactory, partly due to the presence of a large number of young women. The French regiments, 3 and 4 SAS, are separated by a few miles to prevent conflicts, often arising from differing allegiances to General de Gaulle. Prior to the outbreak of war, the British government made plans to build several Emergency Medical Service Hospitals around major cities. One such hospital for Glasgow, built in the grounds of Ballochmyle House near Mauchline, specializes in plastic, reconstructive, and maxillofacial surgery for badly burnt patients, both civil and military. In 1943, it has 1,200 patient beds and over 2,000 female staff, many living on-site and not uninterested in polite conversation with French paratroops.

Belgian paratroops, forming No. 5 (Belgian) SAS Regiment, arrive in Ayrshire after a journey starting from the surrender of the Belgian Army on May 28th, 1940. They undergo several transformations and training courses, culminating in their integration into the Special Air Service Brigade. The Belgian unit, known for its smartness and discipline, avoids separating Walloon and Flemish-speaking sub-units, fostering team spirit. In December 1943, the Belgian Independent Parachute Company moves to Inverlochy Castle near Lochailort for special training. In January 1944, the company commander, Eddie Blondeel, learns that their new location is Moscow, a village in Ayrshire, not Russia, much to the relief of his men. They settle in a hutted camp in the grounds of Loudoun Castle near Galston.

The SAS Brigade includes F Squadron, Phantom, commanded by Major Jake Astor, with a strength of about one hundred all ranks. Each member is an expert in long-range wireless communications, battlefield reconnaissance, and SIGINT to intercept Allied and German tactical radio networks. F Squadron personnel maintain their skills, run the brigade wireless net, man a rear-link to Headquarters Airborne Forces, and train wireless operators for 1 and 2 SAS.

The regiments are equipped mainly with the Jedburgh wireless set, complete with an aerial pack, hand/foot generator, and spare parts packages. Brigade Headquarters has teleprinters and high-powered wireless sets for contact with higher headquarters. Transmissions to and from the field are sent via powerful transmitters owned and operated by the BBC, which also trains some Special Air Service personnel in broadcasting for daily news bulletins.

Additionally, Special Air Service and Phantom patrols have access to a steam-powered generator, solving the problem of electricity supplies but being heavy and noisy unless well-insulated or buried in a mini-bunker.

| Discussion over Role In Operation Overlord |

In March 1944, a major disagreement over the tactical deployment of the brigade in France erupts, focusing on the missions allocated to the five regiments for the period D-1 to D+15. Planners want the brigade to deploy detachments into the immediate rear of the coastal defense zone to interdict German reinforcements and attack Luftwaffe communications centers and airfields on D-1.

These targets, selected by planners with no Special Forces experience, face criticism from experienced officers like Lieutenant Colonels Stirling and Mayne. Issues include making heavy drops in flak-rich areas and lack of ground cover, reconnaissance time, and safe jeep routes during curfew.

The argument is vigorous and sustained, with traditionalists advocating adherence to orders and Special Forces veterans arguing for practical tactics. Airfield attacks are quickly ruled out due to the well-defended locations of Luftwaffe aircraft. The revised plan focuses on interdiction of German reinforcements and supply columns, with jeeps equipped with either a British PIAT or a US 2.75-inch Rocket Launcher for disabling light armoured vehicles.

The debate ultimately leads to the resignation of Lieutenant Colonel Bill Stirling. Major Brian Franks, an experienced hotelier adept at handling crises and disaffected individuals, replaces him, proving to be an inspired commander and helping 2 SAS settle down after its disjointed birth and disturbed formative years.

Two high-level decisions impact the Special Air Service role. First, no uniformed Special Forces are to deploy onto the continent before H-Hour on D-Day to preserve secrecy. This decision covers the Special Air Service, Operational Groups, Jedburgh teams, and Inter-Allied Missions, halting many planned operations. However, Pathfinders for the British and U.S. airborne divisions are exempted, deemed essential for marking Dropping Zones and Landing Zones.

Second, MI9 requests Special Air Service assistance in evacuating evaders and escapers from northern France and southern Belgium. These pools, comprising mainly aircrew evaders and some escapers needing medical treatment, are under threat from the Gestapo and Milice. Operations Marathon and Bonaparte successfully recover evaders, bringing great satisfaction to Special Air Service veterans.

Special Operation Executive’s Air Supply Section, Red Cross medical staff, and Ministry of Food nutritionists devise an Invalid Ration Load to sustain two hundred “weakened” men for one day. These loads, fitted into standard Mark III parachute containers, include meat extract, arrowroot powder, condensed milk, sugar, tea, boiled sweets, salt, cigarettes, matches, chocolate, brandy, and Army biscuits. They are a boon to MI9 reception committees in the weeks before D-Day as travel and food supply movements in France are severely restricted by Allied bombing and Resistance sabotage.

In April 1944, S Force, a land-based deception unit, co-locates with the Special Air Service Brigade in Ayrshire. Equipped with US White Scout cars, S Force’s exact relationship with the Special Air Service Brigade remains unclear, possibly attached for “pay and rations.” The Special Air Service Brigade faces growing administrative problems, leading to the establishment of a separate base organisation in early May, less than five weeks before D-Day.

The new base area is at Williamstrip Camp near Down Ampney, about thirteen kilometres from the brigade holding area at Fairford. The Special Air Service Brigade plans over fifty missions but conducts twenty-eight, focusing on interdiction of German reinforcements and supply columns. Operational planning evolves with input from experienced veterans, but the distance between Special Forces Headquarters and Ayrshire creates communication challenges.

Plans drawn up in late winter and early spring 1944 for Special Air Service operations in support of the first two phases of the invasion envisage around fifty missions. Ultimately, twenty-eight missions are mounted, plus three others: part of Operation Fortitude South, an unsuccessful assassination attempt, and a successful Prisoner of War recovery mission. The “Bill Stirling Resignation Incident” leads to the deletion of tasks to delay Panzer forces, adopting a more sensible alternative involving airborne and air-landing operations to isolate German Panzer forces from the invasion beaches.

To insert as many jeep-mounted detachments as quickly as possible, gliders are used. The Special Air Service Brigade headquarters canvasses its regiments for volunteers to undertake a special, less intensive training course for co-pilots. Six men complete the course and qualify to wear the small co-pilots brevet. X Flight, created to land Special Air Service units behind German lines, is equipped with Hadrian gliders, capable of carrying one jeep and a trailer or a 6-pounder anti-tank gun.

| Disbandment |