| Page Created |

| January 11th, 2026 |

| Last Updated |

| February 22nd, 2026 |

| Germany |

|

| Related Pages |

| Fall Gelb DFS 230, Lastensegelflugzeug Fort d’Ében-Émael Preperations Unternehmen Danzig Fall Gelb, The Maastricht Gateway Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Beton Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Eisen Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Granit Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Stahl |

| Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Granit, May 10th, 1940 |

| Podcast |

| Objectives |

- Neutralise the artillery positions at Fort Eben Emael.

| Operational Area |

| Allied Forces |

- Sturmabteilung Koch

- Sturmgruppe Granit

- 17. Staffel, Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 5

- Flak-Sondereinheit „Aldinger“

| Axis Forces |

- Sturmabteilung Koch

- Sturmgruppe Granit

- 17. Staffel, Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 5

- Flak-Sondereinheit „Aldinger“

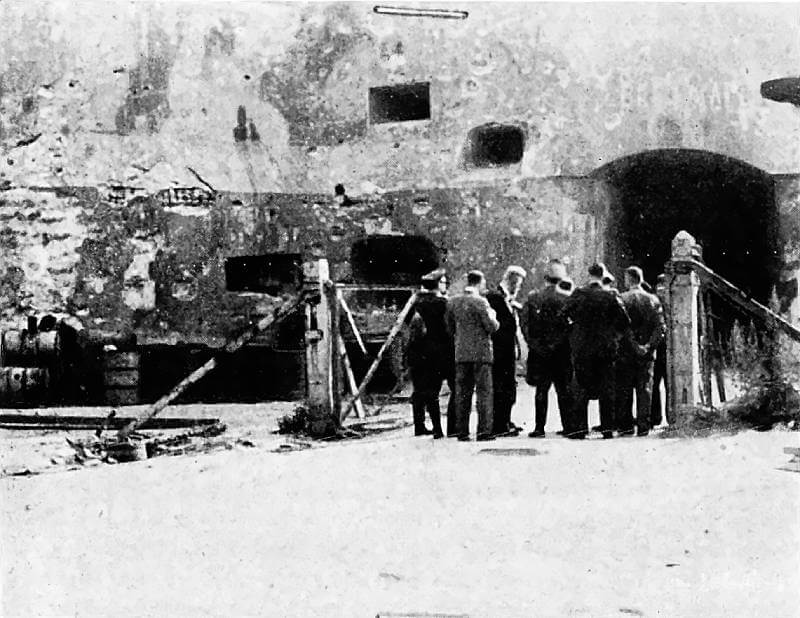

| Fort Eben-Emael |

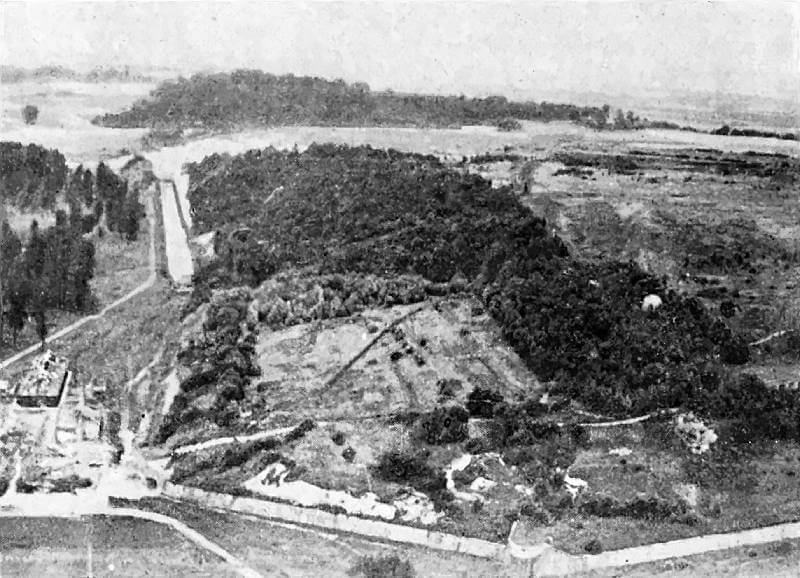

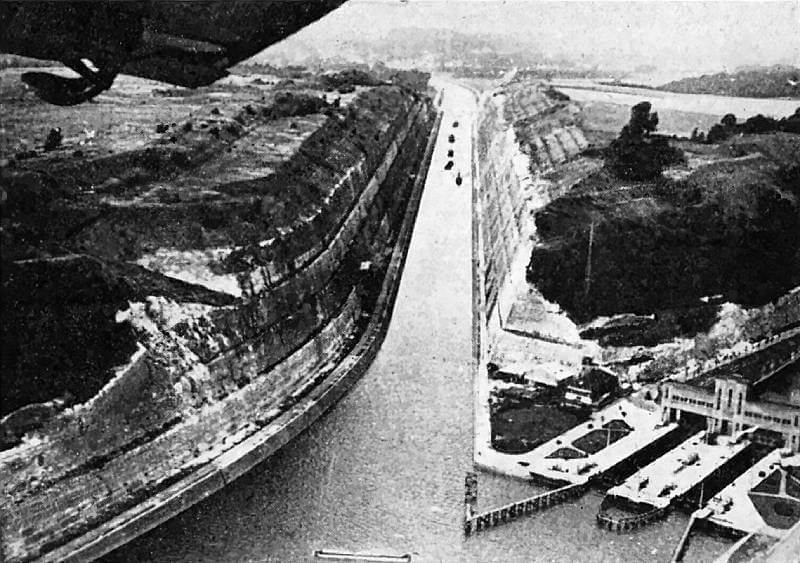

Located between Maastricht and Visé, Eben Emael is built between 1932 and 1935. It covers the Visé Gap to the north. It also controls the main crossings over the Albert Canal from the Netherlands into Belgium to the south. These crossings include the bridges at Veldwezelt, Vroenhoven, and Kanne.

The fort is situated on St Peter’s Hill near Caestert. It rises approximately 60 metres above the Albert Canal. Eben Emael is designed as a reinforced artillery position. It forms one of four new forts constructed east of Liège after the First World War. These strongholds are intended to defend Belgium’s eastern approaches.

At the time of completion, Eben Emael is regarded as the most technologically advanced fortress of its era. Construction costs amount to 24 million Belgian francs. This equals approximately £2 billion in modern value. The fort is constructed in the shape of a rough equilateral triangle. Each side measures approximately 800 metres. The total surface area measures about 75,000 square metres. The superstructure alone covers roughly 45,000 square metres.

Eben Emael functions as a self-contained underground city. It consists of three levels. The lowest level lies almost 60 metres below ground. This level serves as the living area. It contains large galleries, central staircases, and lifts. Oil tanks and water tanks are installed there. Electrical power is generated by six diesel engines. Barracks house the enlisted men. Separate sleeping quarters are provided for officers. Toilets, showers, and washrooms are present. An armoury and a prison are also located on this level.

The intermediate level lies about 40 metres below ground. It consists of tunnels and galleries with a total length of 4 kilometres. With few exceptions, all combat bunkers are accessed only from this level. Ammunition storage rooms are located beneath each bunker. These rooms are connected to the bunkers by lifts and stairways. The ventilation system is also housed on this level.

The upper level contains all firing and observation installations. It includes artillery cupolas and observation cupolas. It includes machine-gun bunkers on the surface. Thick armoured doors separate the various levels and compartments. These doors are hermetically sealed and resemble naval bulkheads. Technical innovations include air conditioning and central heating. A filtration and overpressure system continuously cleans the air and expels dangerous gases.

The garrison numbers approximately 1,200 men. Around 1,000 serve as artillery personnel. Around 200 serve in support roles. With its underground layout and extensive defences, the fort is widely considered impregnable. In the event of war with Germany, the French General Staff expects resistance for at least five days. The Belgian Army’s eighteen divisions rely on the border forts as their first line of defence.

The forts are not intended to stop the German Army alone. Their purpose is to deter attack by increasing the cost of offensive operations. They are also intended to delay an advance. This delay is meant to gain time for Belgian and Allied mobilisation.

On paper, Eben Emael appears well designed for this mission. Its defences include moats and anti-tank ditches. Trenches, minefields, and barbed wire are installed. Blockhouses and artillery cupolas are constructed. False cupolas and observation cupolas are also present. Provision is made for emergency evacuation. Three main exits are built. Six additional emergency exits are constructed.

The fort contains seventeen bunkers. Two additional bunkers are located at Kanne and Hallembaye. Six observation posts are positioned outside the fort. These posts are located at Loën, Caestert, Opkanne, Vroenhoven, and Briegden. All positions are connected to Eben Emael by telephone. The fort is also connected by telephone and radio to the Belgian Army General Staff in Liège.

Eben Emael mounts artillery providing all-round defence. Its primary mission is artillery support for field troops. The guns are manned by two artillery groups. Each group numbers about 500 men. These men rotate weekly between service in the fort and rest. Rest and recuperation take place at barracks in Wonck. Wonck lies four kilometres to the south. Approximately 200 additional personnel serve as electricians, armourers, cooks, medical staff, and clerks. These men are billeted with civilians in the village of Eben-Emael or housed in wooden barracks near the fort entrance. The garrison is commanded by a Major of the Belgian Army. Personnel work eight-hour shifts.

The command structure governing the fort’s artillery is highly complex. This structure dilutes the effective use of Eben Emael’s firepower. The fort commander and his fire-control office may issue firing orders. Target selection remains the responsibility of field commanders. Cupola 120, armed with two 120-millimetre guns and capable of full rotation, falls under Belgian I Corps. Cupola North and Cupola South are retractable cupolas, each mounting two 75-millimetre guns. These are allocated to the commander of the Belgian 7th Infantry Division.

Maastricht 1 and Maastricht 2 each mount three 75-millimetre guns. These positions fall under the commander of the 18th Infantry Regiment. Visé 1 and Visé 2 also each mount three 75-millimetre guns. Visé 1 is controlled by the commander of the 2e Grenadier Regiment. Visé 2 falls under the Lower Meuse regional command.

Defence of the Albert Canal is shared with the Belgian 2e Grenadier Regiment. The regiment is authorised a strength of 3,400 men. This includes 3,000 enlisted soldiers, 300 non-commissioned officers, and 100 officers. Like many Belgian units, it is understrength. It numbers approximately 2,600 men.

The regiment defends a frontage 9 kilometres wide and 1.5 kilometres deep. It deploys in depth along the Meuse River and the Albert Canal. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions hold the forward line from Kanne through Emael, Loën, and Lixhe. The 1st Battalion occupies a rear line from Fall to Weer and Wonck.

Artillery support is provided by the 105th Artillery Battalion. This unit belongs to the Belgian Army’s 20th Motorised Artillery Regiment. On paper, the defences appear imposing. In reality, serious deficiencies remain. Barbed wire, minefields, and trenches are insufficient near the bunkers and on the superstructure.

The designers do not anticipate an airborne assault. Major Jean Fritz Lucien Jottrand commands the garrison. He recognises the flat roof as suitable for aerial resupply. It instead serves as a football field. This supports morale in a force with weak esprit de corps. This use largely explains the absence of obstacles.

Several cupolas lack firing periscopes. These installations are therefore ineffective. The fort lacks sufficient explosives to seal the main gallery after a breach. Belgian Army regulations require such measures. Many telephone sets are removed for use at a rifle range located 30 kilometres away.

The surrounding hills restrict effective fire toward Aachen and Maastricht. If Maastricht falls, the fort cannot engage the area effectively. The original ventilation system is defective. A replacement system is only partially installed. Anti-aircraft defence is inadequate. Only four anti-aircraft machine guns are available. All are positioned on the superstructure.

Training standards within the garrison are poor. Many soldiers have never fired live ammunition. Although trained as artillerymen, they are expected to fight as infantry. They are also required to launch immediate local counter-attacks after a penetration. Morale is low. Absenteeism is common. Many soldiers suffer throat infections caused by dust and mould. Others are absent on special leave granted to miners, farmers, and fathers of large families.

These shortcomings are known to the Belgian senior command. Efforts to correct them are underway. The war begins before these measures can be completed.

| Multimedia |

| Operational Planning |

Together with Oberstleutnant Bruno Bräuer, Kommandeur des Fallschirmjäger-Regiments 1, Student selects the assault leaders. He assigns Hauptmann Walter Koch the task as operational leader. He assigns Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig the task of capturing Fort Eben-Emael.

The task of the assault is assigned to a parachute engineer platoon because no other qualified engineers exist within the airborne forces at that time. The German airborne arm remains small in 1940. Luftwaffe engineer personnel lack the specialist training required for complex assault operations. These men are regarded as infantry engineers rather than fully trained combat engineers. The platoon assigned to the mission originates from the Heeres-Pioniertruppe. Its members are identified by the black piping worn on their shoulder straps. Although the unit is transferred to the Luftwaffe, its training, doctrine, and professional identity remain those of Army combat engineers.

The platoon benefits from long and comprehensive preparation, particularly for assault missions. It is regarded as confident and disciplined. The engineers, like the parachute infantry of Hauptmann Walter Koch, are considered superior soldiers in training and morale. No recorded instance exists of a soldier attempting to withdraw. Every member of the unit is a volunteer. Each man first volunteers for parachute training. He then joins a Fallschirmjäger infantry battalion. From there he volunteers again for parachute engineer service. The unit is composed entirely of motivated and experienced personnel.

High morale characterises not only the airborne formations. At this stage of the war, the Heer, Luftwaffe, and Kriegsmarine all display exceptionally strong morale. Reactions to stress are not always restrained. Nevertheless, overall confidence within the German armed forces is high during this period.

A clear distinction exists between Army-trained parachute engineers and Luftwaffe parachute engineers. Luftwaffe engineer units are initially trained for a narrow mission profile. Their task focuses on demolition operations. These units are expected to jump in, destroy assigned objectives, and attempt to return by any available means. During manoeuvres in 1937, recovery by aircraft is planned but not executed. In practice, returning personnel are issued railway tickets. By contrast, the Heer organises its airborne units from the outset for a wide range of tactical and operational missions.

The Army parachute engineers are trained and prepared for more than a supplementary role. Their qualifications are such that during the winter of 1938 to 1939 they are tasked with instructing other soldiers in demolition techniques and engineer skills within the regiment.

For the assault on Eben Emael, the parachute engineer platoon is reinforced. Its original strength of 40 to 50 men is increased to between 70 and 80. The additional personnel are Fallschirmjäger drawn from the parachute infantry company of Hauptmann Koch.

Orders for the operation are issued in November by General der Flieger Kurt Student. A meeting is held at the divisional staff at Berlin-Tempelhof. At this meeting, Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig, Hauptmann Walter Koch, and Oberst Bruno Bräuer, Kommandeur des Fallschirmjäger-Regiments 1, are informed of the mission. Shortly thereafter, Koch’s 1. Fallschirmjäger-Kompanie and the reinforced parachute engineer platoon are detached from the 7. Flieger-Division.

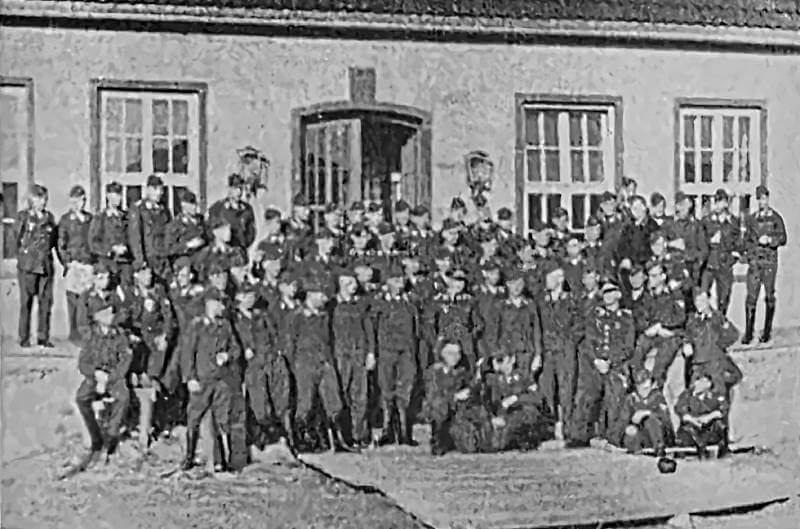

Later that month, General der Flieger Student orders the formation of a special airborne task force at Hildesheim. The unit is organised at battalion strength and designated Sturmabteilung Koch. It consists of carefully selected officers and men from the German airborne forces. Strict security measures are imposed. Training begins using Polish fortifications at Gleiwitz to practise assault techniques.

Sturmabteilung Koch is commanded by Hauptmann Koch. The formation consists of 11 officers and 427 men. This includes 42 glider pilots and 4 reserve glider pilots under Leutnant Walter Kiess. The air component includes an additional 16 officers and 182 men. It incorporates 44 Junker 52 tow pilots with 4 in reserve. A second reserve group includes 6 Junker 52 pilots with 1 pilot in reserve. In total, 84 gliders and tow aircraft are allocated.

The air component is organised into four Staffeln. Each Staffel supports one assault group. Each Staffel is divided into two Startegruppen. Each Startgruppe contains between 3 and 6 Ju 52 aircraft. A fifth Staffel holds all reserve aircraft and crews.

For the assault phase, Sturmabteilung Koch is divided into four Sturmgruppen. Each group corresponds roughly to an understrength company. Each group is tasked with seizing and holding a specific objective until relieved by advancing Heer formations.

Sturmgruppe Granit is commanded by Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig. Its mission is to neutralise the outer works of Eben Emael and hold the position until relieved by Pionier-Bataillon 51. The group consists of 2 officers and 83 parachute engineers. It deploys in 11 gliders.

Sturmgruppe Eisen is commanded by Leutnant Martine Schächter. It is tasked with securing the bridge at Kanne until relieved by Infanterie-Regiment 151. The group consists of 2 officers and 88 men. It deploys in 10 gliders.

Sturmgruppe Beton is commanded by Leutnant Gerhard Schacht. Its mission is to secure the bridge at Vroenhoven until relieved by Infanterie-Regiment 162. It consists of 5 officers and 129 men. Because of the importance of this objective, Hauptmann Koch accompanies this group.

Sturmgruppe Stahl is commanded by Leutnant Gustav Altmann. Its task is to secure the bridge at Veldwezelt until relieved by Infanterie-Regiment 176. The group consists of 1 officer and 91 men.

With Sturmabteilung Koch deployed against Belgian objectives, the remainder of the 7. Flieger-Division is assigned operations against Dutch airfields and bridges.

Every member of the parachute engineer platoon is an experienced Fallschirmjäger. All are veterans of the Polish campaign. All are trained demolition specialists. The unit is unique within the airborne forces in being composed entirely of engineers. All members are volunteers. Many are accomplished glider pilots from the pre-war period. Over two years, the unit develops into a cohesive formation characterised by strong mutual trust.

At Hildesheim, the unit is housed in a gymnasium at the airfield. The mission is explained without naming the objective. Security restrictions are extreme. The area is guarded continuously. Movement is strictly controlled. All outgoing and incoming correspondence is censored. Soldiers are forbidden to use telephones or send mail.

Parachute insignia and distinctive uniform items are removed. This measure proves deeply unpopular. Special meals are provided. Contact with other units is prohibited. Leaving the quarters without permission is forbidden. Violations are punished severely. In one instance, three soldiers leave the Kaserne for coffee. They are apprehended, tried, and sentenced to death. The sentence is not carried out, but the incident demonstrates the seriousness of the security measures.

A detention cell is made available for disciplinary purposes. Because of security requirements, only members of the unit are permitted to guard it. Informal assistance to detained comrades occurs when possible.

Security is regarded as vital. Operational success and survival depend entirely on surprise. No leave is granted. Units operate under false names. All parachute insignia and uniforms are removed. Glider training is conducted on the smallest possible scale. Gliders are dismantled, transported to Köln in civilian vehicles, and reassembled in guarded hangars surrounded by wire obstacles.

Because transport capacity is limited, the parachute engineer platoon is relocated to Köln and Düsseldorf. This reduces travel time to the departure airfields at Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof. Personnel live under assumed identities. Their role and mission remain unknown to outsiders.

Training intensifies under close supervision. Glider landings are rehearsed repeatedly. Assault procedures are refined in detail. Preparation time is limited to 10 to 14 days. The initial target date for the attack is November 13th, 1939.

At this stage, confidence in the mission is high. Trust in the command structure is absolute. No part of the assignment is regarded as impossible. Morale and discipline replace doubt.

Planning responsibilities rest with the assigned officers. Technical expertise in assaulting fortifications shapes training and preparation. Logistical and administrative support is provided by higher command. Tactical planning is developed through detailed discussion with non-commissioned officers. Sand-table models are used to refine the plan.

By February 1940, demolition training takes place on the former Czechoslovak Beneš Line. Casemates are assaulted using flamethrowers and heavy explosives, including Bangalore torpedoes. These fortifications prove more robust than anticipated. At the time, however, the relative strength of Belgian defences remains uncertain.

Additional instruction is conducted at the Pionierschule at Karlshorst. Fortress construction principles are studied in detail. Belgian deserters are interrogated. Their information confirms existing intelligence assessments. Confidence increases steadily.

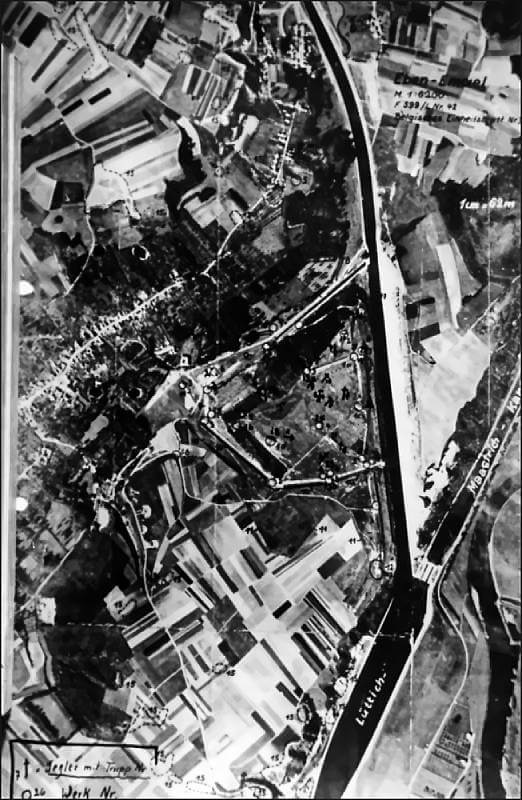

Detailed intelligence on Eben Emael is provided. This includes aerial photographs and comprehensive engineering drawings of the fort. Stereoscopic images allow the identification of elevations and depressions. Key structures are highlighted by intelligence officers. All references to the fort’s name and the Albert Canal are removed from documentation. No soldier is informed of the objective’s identity or location. Absolute secrecy is maintained throughout preparation.

For the assault, Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig and every Fallschirmjäger under his command carry miniature maps of Eben Emael. These maps are stored in small pocket-sized cases and are issued individually before the operation.

Training for the assault is comprehensive and continuous. Aircraft loading procedures are rehearsed repeatedly. Rapid embarkation, unloading, and immediate exit drills are practised under realistic conditions. Training is never conducted as a single complete exercise. Individual tasks are broken down into isolated components. This method prevents outside observers from understanding the purpose of the training.

Demolition training and ground assault techniques are conducted at the Pionierschule in Dessau. Further training takes place in the Sudetenland. There, Czech fortifications are used as training objectives. These fortifications prove more difficult to assault than those at Eben Emael. Joint training is conducted with the glider pilots. These pilots are required to master infantry and pioneer combat skills. They are trained not only to understand these tasks but to execute them under combat conditions.

For the operation, Oberleutnant Witzig organises his force into eleven squads. Each squad consists of two or three Unteroffiziere and four to six enlisted soldiers. This structure reflects the carrying capacity of the Junker 52 tow aircraft and the DFS 230 gliders. Each squad is assigned sufficient equipment to complete its task independently. Every squad is responsible for capturing two emplacements or casemates. All squads are also required to be capable of assuming the mission of any other squad rendered ineffective. The first nine squads receive specific objectives. The tenth and eleventh squads are designated as the reserve.

Unlike conventional aircraft pilots, a glider pilot retains command authority until landing. After landing, the pilot cannot disengage from combat. For this reason, glider pilots are fully integrated into the assault detachments as combat engineers. Each pilot is assigned to a specific squad. This ensures reliability and cohesion during ground combat.

Command arrangements place Oberleutnant Witzig initially with the eleventh squad. His deputy company commander, Leutnant Delica, accompanies the first squad. The planned date of the operation is postponed several times. Training continues without interruption during these delays. Precision landing with explosives on prepared airstrips and open terrain is rehearsed. Rapid disembarkation while fully equipped is practised repeatedly.

Special equipment for the assault includes flamethrowers and collapsible assault ladders. These ladders are designed and constructed by the assault troops themselves. The operation also requires approximately two and a half tonnes of explosives. Most of these explosives consist of hollow charge devices. These devices are employed for the first time in combat during the assault on Eben Emael. Their primary purpose is the penetration of armoured cupolas.

Two secret weapons are prepared for the operation. The first is the combat glider. The DFS 230 is developed to transport assault squads intact and ready for immediate action. This capability is unattainable with conventional parachute insertion.

The glider also enables the assault force to transports approximately five tonnes of explosives. This load includes twenty-eight shaped charges weighing fifty kilograms each, twenty-eight shaped charges weighing twelve point five kilograms each, eighty-three charges weighing three kilograms each, and more than one hundred additional explosive devices. The assault force is also equipped with six medium machine guns, eighteen submachine guns, fifty-four rifles, eighty-five pistols, more than thirty thousand rounds of ammunition, and nearly seven hundred and fifty hand grenades. Each assault squad carries a substantial combat load.

The second secret weapon is the shaped charge. These devices are employed operationally for the first time during the assault. Witzig introduces his men to these charges in January 1940. No prior doctrine exists for their tactical use. No formal training programme is available. Instruction is provided directly by engineers and technicians from the explosives industry involved in their development.

Two types of shaped charge are issued. One weighs fifty kilograms. The other weighs twelve point five kilograms. The larger charge is transported in two hemispherical sections. It is capable of penetrating armoured cupolas with thicknesses up to twenty-five centimetres. Where armour thickness reaches twenty-eight centimetres, internal damage is still sufficient to disable weapons and crews through fragmentation. In areas of greater thickness, repeated detonations at the same point are required. The smaller charge penetrates armour between twelve and fifteen centimetres. It is also used for precision demolition of embrasures and artillery openings. All charges are fitted with ten-second fuses.

The assault troops are trained to place shaped charges directly onto armoured cupolas. The large charge is assembled on site from its two halves. Detonation causes fragments from the interior of the cupola to ricochet at high velocity. This effect destroys equipment and incapacitates personnel inside. Breaching the armour is not always required. Rendering the position inoperable is sufficient to neutralise the weapon.

Extensive experimentation determines the minimum safe distance between the operator and the charge. A ten-second delay is selected as optimal. All assault troops receive training with the shaped charges. Only a limited number of soldiers carry the devices due to restricted availability. Remaining personnel carry standard infantry weapons.

As a final deception measure, parachute-deployed dummy figures in uniform are dropped west of the Albert Canal. These decoys are intended to simulate additional airborne landings. The measure successfully creates confusion within Belgian command channels and contributes to operational surprise.

| Multimedia |

| The Way In |

After six months of strict isolation and repeated postponements, the alert is issued during the afternoon of May 9th, 1940. On that day Adolf Hitler releases a proclamation to German soldiers on the Western Front. The proclamation declares that the battle beginning that day will determine the fate of the German nation for the next thousand years and calls upon the troops to fulfil their duty with the blessing of the German people.

That evening, the assault detachment moves by truck from the Seldorf Flakkaserne to the airfield at Köln-Ostheim. The unit is quartered in a newly constructed building isolated from other formations. Equipment is loaded inside the hangars. The troops then await further orders. Platoon leaders conduct final inspections and confirm readiness. At 21:00, all platoons report prepared for action.

In the early hours of May 10th, 1940, reveille is sounded at 02:45. The men of Sturmabteilung Koch assemble at the airfields of Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof. At 03:30, the troops form up in full equipment and prepare to embark. Final instructions are issued. The order to board the aircraft follows. The men move to the gliders and take their seats. At exactly 04:30, the tow aircraft begin their take-off into the pre-dawn darkness. The take-off time is selected to allow all four assault groups to land simultaneously. The planned landing time is 05:25, five minutes before formations of the Wehrmacht cross the frontier.

The aircraft depart in complete darkness and climb by circling southwards. By 04:50, all forty-two unmarked gliders are airborne. They then turn west and follow a route previously marked by radio beacons and searchlights. By the time the formation reaches Aachen, the aircraft and gliders have climbed to a height of 2,500 metres. At this altitude, the gliders possess a gliding range of approximately 30 kilometres. The Belgian border lies only 10 kilometres ahead. Fort Eben Emael is 25 kilometres distant.

Sturmgruppe Granit proceeds toward its objective in eleven DFS 230 assault gliders. Each glider is towed by a Junkers Ju 52. The corrugated aluminium fuselage of the DFS 230 amplifies engine noise within the cabin. Communication inside the aircraft relies on hand signals, klaxons, and lights. The interior is stripped to essentials. Canvas seating lines the fuselage. German Fallschirmjäger are transported to the objective under these conditions.

At 05:15, the tow aircraft release the DFS 230 gliders. Each glider still has approximately 30 kilometres to travel to its landing zone. During the flight, two gliders are lost, including the glider carrying Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig. Shortly after crossing the Rhine, the Junker 52 towing Oberleutnant Witzig’s glider dives sharply. The manoeuvre avoids a collision with another aircraft. The sudden dive snaps the tow cable. The manoeuvre places excessive strain on the tow rope, which parts under the load.

While the main formation continues its descent westwards, Witzig’s glider remains alone in the air. Witzig orders the pilot to turn back toward the Rhine. The intention is to cross the river again. The departure airfields at Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof lie on the eastern bank. To attempt a renewed start, the glider must first regain the east side of the Rhine.

At 05:25, the remaining nine gliders arrive over the fort. Defensive fire is finally opened from four Belgian anti-aircraft machine guns mounted on the superstructure of Eben Emael.

| Multimedia |

| Ziel Granit |

At 05:25 hours on May 10th, 1940, the first German glider lands on the roof of Fort Eben Emael. Each Glider carries a Trupp of German troops carrying six Rifles, two MP-40 Submachine guns, one M34 Machinegun and one Flamethrower. The glider also carries one 4 metre folding ladder, one Flare pistol, two 50-kilogram hollow charges, three Bangalores torpedoes, two 12.5-kilogram, one 6-kilogram pole charges, five 3-kilogram, one 20-kilogram crate, five bags of charges and two large flag markers

| Gruppe 1, Maastricht 2 (Objective 18) |

The north-facing casemate Maastricht 2 mounts three 75-millimetre guns and contains artillery observation post Eben III. This objective is assigned to Feldwebel Niedermeier and Gruppe 1 of Sturmgruppe Granit. Leutnant Delica accompanies the assault as deputy commander of the Sturmgruppe.

The DFS 230 glider is flown by Feldwebel Raschke. The approach speed is high and results in a heavy landing. Glider 1 encounters intense antiaircraft fire on approach. The pilot takes evasive action. The hard landing stuns Leutnant Delica, Feldwebel Niedermeier and Trupp 1. The glider lands cleanly at 04:25 hours in open ground between Maastricht-2 and the 120-millimetre turret bloc. The men recover quickly and execute their rehearsed drill.

Inside the observation post, the Belgian sergeants do not observe the landing. The first indication of the attack comes when unfamiliar boots appear on the roof. A warning is shouted to the gun crews below. Before further action can be taken, a hollow charge detonates. The charge is placed by Obergefreiter Drucks and Feldwebel Niedermeier.

The first detonation does not penetrate the armour. It creates a shallow crater. Despite this, the internal effects are severe. Steel fragments tear loose inside the cupola. Both Belgian sergents inside the observation post are killed.

A second shaped charge weighing 12.5-kilograms is brought forward by Obergefreiter Kramer and Obergefreiter Graf in the embrasure of the first 75-millemetre gun. The explosion tears the gun from its mounting. The weapon is hurled into the rear of the gun chamber, killing additional defenders. The blast leaves an opening measuring 60 by 60 centimetres. Niedermeier and two others throw grenades through the opening and enter firing.

Two Belgian gunners are dead. One is wounded. Others are burned or stunned by the blast. Two signallers are missing. As wounded personnel are dragged down toward the intermediate level, a three-kilogram charge detonates inside the barrel of Gun Number Two. While the wounded receive aid, the explosion destroys the barrel of the second gun. The Belgian Sergent Poncelet orders the remaining crew to withdraw to the lower level. The Germans pursue them inside and down the stairway. Poncelet’s men quickly seal the lower airlock doors. Access to the intermediate level is secured.

Machine-gun fire rattles above them. Smoke and dust fill the casemate. The gap is large enough for a man to crawl through. Entry is delayed until visibility improves. Feldwebel Niedermeier and two Fallschirmjäger enter the vacated casemate wearing gas masks. Several MP 38 bursts are fired down the stairwell to hasten the Belgian retreat.

On the intermediate level, Belgian personnel attempt to seal the access. Steel beams are fitted into their channels. Sandbags are packed between the steel doors. Fear of pursuit into the interior of the fort is evident. Meanwhile, the mortally wounded Caporal Verbois is carried out through the shattered embrasure. Medical treatment is impossible. He dies shortly afterwards.

Within the opening minutes of the assault, a second offensive casemate is neutralised. Of the remaining artillery positions, three are under direct attack. Two remain untouched, likely due to incomplete identification during intelligence preparation.

Fire from Cupola Sud begins to fall near Maastricht 2. Niedermeier orders his men into the casement for cover. As planned, Feldwebel Niedermeier dispatches Obergefreiter Drucks north across the open surface to locate Oberleutnant Witzig and report success at Objective 18. While the Gruppen reorganise and secure prisoners, glider pilots not engaged in prisoner handling lay out aircraft recognition panels beside the captured casemates. These panels serve as signals for Junker 87 dive bombers standing by to support Sturmgruppe Granit if further resistance proves difficult.

Leutnant Egon Delica’s Glider Gruppe 1 attacks Objective 18, known as Maastricht-2. Its guns, together with Ma-1, cover the three northern glider landing zones. Sergent Poncelet, commander of Maastricht 2, orders emergency barriers erected. Three defenders are dead and seventeen wounded. Sandbags and steel rods seal access doors to block entry into the tunnel system.

| Gruppe 2, Cupola 120 (Objective 24) |

At the centre of the open upper surface stand the fort’s most powerful weapons. These consist of twin 120-millimetre guns mounted in a large revolving steel cupola. The structure closely resembles the false cupolas at Objectives 14 and 16, which have already been attacked on the northern part of the surface. Cupola 120 is assigned to Feldwebel Max Maier and Gruppe 2 of Sturmgruppe Granit. Their DFS 230 glider, however, fails to reach the fort after the tow rope parts. As a result, the cupola is not neutralised during the first wave of the assault.

This failure presents a potentially serious danger. German armoured spearheads are expected to advance into the effective range of the 120-millimetre guns. Inside the steel cupola, Sergent René Cremer observes events through the gun sight. He watches gliders skid to a halt on the surface and hears the repeated heavy detonations of hollow charges against neighbouring casemates. His observation is severely restricted. The cupola lacks a functioning periscope. To survey the area, the entire cupola must be traversed slowly.

Because no rapidly rotating periscope is available, the only observer capable of reporting from Cupola 120 can provide only fragmentary information. Despite repeated requests from the command post, details remain incomplete. Cremer observes a group of German paratroopers sheltering beneath the wing of a glider located between Cupola Nord and his own position. This information is transmitted immediately to the command post together with a request for permission to open fire.

Eventually an order is received to engage targets on the slope in front of Bloc I using shells with very short-delay fuses. Orders are issued inside the cupola. The turret begins to traverse. Ammunition is placed into the hoist. At this point, a series of mechanical failures occurs. The hoist ceases to function. The ammunition loader discovers that the shafts of the loading pincers are missing. A man is dispatched to the repair workshop. While waiting, the crew attempts to repair the hoist and open ammunition crates manually.

The command post is informed that the hoist is inoperative. Without the pincers, the crew opens ammunition boxes by hand using pocket knives and hammers. Eventually, shells intended for surface clearance are unpacked and carried up to the guns. Cremer attempts to aim the cupola by sighting through the barrel of one gun. He realises that the line of fire passes above Cupola Nord. Despite this, the decision is made to fire regardless.

A further malfunction occurs within the turret mechanism. The counterweight components cannot be separated. This problem is reported by Caporal van Gelooven. Observers are assigned to monitor the sight telescope from the dugout while Cremer descends to the Intermediate Level. Inspection reveals that the clutch does not disengage and the counterweight fails to drop. Attempts to operate the loading mechanism manually also fail. Either the shell weight or insufficient pressure from the rammer prevents proper loading. Each attempt ends with the mechanism returning to its original position.

The corporal continues efforts to repair the system. He is experienced but expresses doubt that the mechanism can be restored. This assessment proves accurate. Without coming under direct attack, Cupola 120 is rendered inoperative. The Belgian crew remains occupied with repair attempts while the battle unfolds elsewhere.

| Gruppe 3, Maastricht 1 (Objective 12) |

The final position capable of threatening the bridges is Maastricht 1. This western cupola mounts three 75-millimetre guns. Maastricht 1 is assigned to Feldwebel Arent and Gruppe 3 of Sturmgruppe Granit. Further tasks assigned to Feldwebel Arent include destruction of the generator exhaust tower and action against Bloc II. These objectives are assessed as low priority. Neither forms part of the fort’s offensive artillery system.

The glider is flown by Hauptfeldwebel Supper. The glider circles the fort twice before landing. During the landing approach, the DFS 230 glider comes under machine-gun fire at a height of approximately thirty metres. A steep banking dive brings the aircraft down safely. The glider skids to a halt roughly 20-metres east of the objective. Feldwebel Arent exits first and urges his men forward as they struggle under the weight of the shaped charges.

A search for an external access door proves unsuccessful. The casemate is silent and without observation capability. Maastricht 1 has no observation cupola. No obvious method exists to neutralise the position except through the gun embrasure. They attempt to fix a charge to the gun barrels. Preservation grease prevents adhesion. A 50-kilogram charge proves too large for the embrasure of Gun Number One. It is replaced by a 12.5-kilogram charge. Arent attaches the 12.5-kilogram charge to the ball joint at the base of gun number three. The fuse is ignited. Feldwebel Arent withdraws for cover.

The assault troops remain too close to the casemate at the moment of detonation. Familiarity gained during training contributes to the error. The explosion throws the Fallschirmjäger to the ground and stuns them. After a brief interval, the men return to examine the effect. Inside Maastricht 1, conditions are chaotic. The explosion hurls the Belgian gunner Langelen from his position beside the gun into the telephone room. The seventy-five millimetre gun is torn from its mounting. It is flung across the casemate, crushing Soldat Borman against the ventilator, before tumbling into the stairwell where it comes to rest.

Daylight penetrates the interior through the breach, carrying dust and smoke. Sergent Gigon, badly concussed, locates two wounded men by their voices and carries them down to the lower level. The blast has also ignited propellant charges from the 75-milimetre ammunition. Thick black smoke fills the casemate. The black smoke pours from a wide breach. Groans echo inside. The lights fail. The air smells of burned propellant.

A breach less than sixty centimetres square is torn through concrete and steel. Thick, oily smoke pours from the opening. Moans are audible from inside. Belgian gunners regain consciousness amid burning propellant charges ignited by the blast.

Sergent Gigon returns for a third ascent toward the gun chamber. The propellant charges are now burning fiercely. Smoke becomes so dense that his gas mask obstructs breathing. The sound of MP fire and nine millimetre Parabellum rounds ricocheting from the concrete walls forces him back. He staggers down the stairwell and collapses into the arms of one of his men. Before evacuation to the fort hospital, he reports to Lieutenant Deuse, who is assembling gunners for a counter-attack toward the upper level. Sergent Gigon reports that wounded personnel remain in the gun chamber. Enemy movement is clearly audible above.

Arent throws two hand grenades into the opening before entering the casemate feet first through the breach. He advances by touch through the smoke-filled interior. He reaches a wounded Belgian gunner who is barely conscious but not severely injured. The prisoner is dragged to the opening and handed over to Gefreiter Kupsch and Gefreiter Stopp, who have also entered the casemate. Two further Belgian soldiers are located. One suffers gunshot wounds. Both are removed through the opening.

The surviving crew faced with further explosions, grenades, and German sub-machine gun fire, withdraws to the lower level. Fire from Cupola Sud soon falls outside the position. The section takes shelter within the casement. Arent notices a stairway descending into the fort. From below, he hears the Belgian troops moving back up the stairs. Sounds of a Belgian counterattack forming below become audible. To disrupt it, Feldwebel Arent drops a 2.5-kilogram explosive charge down the shaft. The detonation in the confined space produces a violent concussion. The German assault troops are thrown against the concrete walls and temporarily stunned. However, they remain unharmed. Silence follows from below. Interior lighting extinguishes.

Arent and two men go down 118 steps. Two heavy steel doors block further access. Hours later, he returns with a 50-kilogram charge. He shortens the fuse and detonates it. Six Belgian defenders are killed. The staircase to the surface is destroyed. Unable to breach the doors, Arent withdraws to the roof.

Meanwhile, artillery fire from Cupola Sud has ceased. Trupp 3 immediately attacks Block 02. A hollow charge neutralises the position. The section remains between Maastricht 1 and Block 02. It disrupts Belgian patrols as they approach. In a remarkable reversal, the men use one of the captured 75-millimetre guns to fire against those patrols.

| Gruppe 4, Mi Nord (Objective 19) |

Mi Nord is sited to dominate the open upper surface of the fort. The site is equipped with three heavy machine guns, two armoured searchlights, one artillery observation cupola, and one light machine gun covering the entrance. The Eben 2 observation post sits on top of the bloc. Only a small part of the bloc crew is present. These men have moved to the lower level on their own initiative. The remainder assist with evacuating the external barracks. It is capable of delivering lethal machine-gun fire onto the southern casemates, where the main body of Sturmgruppe Granit is engaged. The position is therefore of critical importance.

Shortly before 04:30, 2 Belgian non-commissioned officers, Vossen and Bataille, occupy the observation post Eben II on top of Mi Nord. They observe the gliders and movement on the fort surface. Before further action is possible, an explosion strikes the position.

The glider lands 80 metres from the target. Wenzel suffers a bloodied nose during the landing. The assault is led by Feldwebel Wenzel. Immediately after landing, he advances at once toward the bunker. Vossen and Bataille spot the Germans as they approach the bloc. They open fire immediately. Wenzel climbs the earth bank on the right and reaches the roof. A small opening exists in the observation cloche roof for the periscope. The periscope is withdrawn when the Germans are seen. Feldwebel Wenzel carries a 1 kilogram charge with a 4 second fuse. The charge is armed. After a brief delay, it is dropped through the periscope opening into the casemate.

At the same time, the remainder of Gruppe 4 arrives with the 50 kilogram hollow charge. It is placed directly on top of the cupola and detonated. Both Belgian non-commissioned officers in the observation post are killed. A 12.5 kilogram charge is then used against the south-facing machine-gun embrasure. The blast detonates but does not penetrate the armour. The concussion forces the Belgian crew to abandon the position.

The second 50-kilogram charge is brought forward in 2 parts. The rest of the Gruppe takes up firing positions in the bushes in front of the rampart. The machine gunner Polzin suppresses the machine-gun embrasures with fire. The charge is suspended in front of the embrasure and detonated. The blast produces a severe shock wave even at a distance of 4 metres. A large breach is torn into the concrete wall. Entry into the casemate is now possible. Meanwhile, a 12.5-kilogram charge destroys the south-facing machine-gun embrasure.

Wenzel and several men enter the bloc. Thick smoke fills the interior. The machine-gun crew is dead. The searchlight is destroyed. At this moment, the internal telephone rings. Wenzel answers the call. A French voice speaks on the line. Wenzel does not understand the language. He answers in English, stating simply that the Germans are present. The voice on the other end responds in shock.

The attackers place a signal flag on the roof. Overflying German pilots can identify the captured position. The team secures the bloc against counter-attack and defensive posts are established. Mi-Nord offers a commanding view of the fort. It becomes the German command post.

Feldwebel Wenzel establishes a command post against the rampart beside Mi Nord. The Gruppe is deployed in a defensive perimeter. The location provides excellent observation across most of the fort, except for the southern and western slopes obscured by vegetation. The Gruppe waits for Witzig’s arrival.

| Multimedia |

| Gruppe 5, The Anti-Aircraft Position (Objective 29), Bloc IV (Objective 30) |

The glider of Gruppe 5, commanded by Feldwebel Erwin Haug, encounters heavy resistance on final approach. The glider is flown by Feldwebel Heiner Lange. Belgian machine guns open fire as the glider descends. The fire reveals the target’s location to the pilot. He steers directly toward the muzzle flashes.

Heavy fire is encountered from both sides during the final approach. The direction of the fire clearly identifies the objective. This allows a precise landing despite intense opposition. Bullets tear through the fabric skin of the glider and strike the steel framework.

The glider descends extremely low. The left wing strut strikes a machine-gun position and tears the weapon from its pit. The aircraft comes to a halt beside a second emplacement. One Belgian gun is knocked over by the impact. The glider stops immediately next to the remaining position.

Feldwebel Lange opens the cockpit, releases his harness, and climbs onto the edge of the glider. He jumps directly into the shallow machine-gun pit. Four Belgian gunners are sheltering inside. Lange carries a pistol in his right hand and a dagger in his left. The Belgian soldiers immediately surrender.

At the same moment, Feldwebel Haug throws a Stielhandgranate into the pit, unaware that Lange has entered it. The grenade malfunctions and only the detonator functions. No one is injured. The incident narrowly avoids friendly casualties. Seeing that Lange has control of the situation, Feldwebel Haug turns his attention to a second machine-gun pit.

Three Belgian gunners in the adjacent position continue firing sustained bursts. Feldwebel Haug advances with the remainder of Gruppe 5. Two Fallschirmjäger rush forward, firing MP 38 submachine guns as they move. A second Stielhandgranate is thrown into the pit. This grenade detonates fully. One Belgian soldier is killed. Two others are stunned and taken prisoner.

With the surrender of the anti-aircraft crews, the Fallschirmjäger of Gruppe 5 are free to assist in suppressing resistance in the nearby hut. Feldwebel Lange remains behind to secure the prisoners. He orders them out of the pits. Additional Belgian gunners arrive from neighbouring positions. Lange suddenly finds himself guarding between fourteen and sixteen prisoners.

Gruppe 5 attacks the small observation bell on top of Bloc IV. The bell is located close to the former machine-gun pits. Inside, the Belgian observer Furnelle has a severely restricted field of vision. He does not observe the glider landings. As he attempts to report activity, a hollow charge detonates against the bell. Furnelle is killed instantly. Simon is seriously wounded. The remaining crew inside the bloc are deafened but remain at their post.

Other defenders fire from a rear window toward Cupola Nord and Gruppe 8. As Cupola Sud opens fire across the fort roof, Trupp 5 responds. Two 50-kilogram hollow charges are placed on the cupola. The detonations shake the structure and dislodge gun mountings. Belgian gunners continue firing but require lengthy realignment after each salvo. Haug then observes trouble near Cupola Nord. Feldwebel Unger’s glider has landed under heavy fire. One man lies wounded on the wing. The rest are pinned down. Haugh moves forward to assist and comes under fire himself. The two sections combine their efforts. They destroy the machine-gun position at close range. The cost is severe. Two men are killed. One is badly wounded. Several others are injured. Despite the damage, artillery from Cupola Sud resumes fire across the fort roof.

Cupola 120 remains active. This central position mounts 120-millimetre guns. Responsibility for its destruction lies with Feldwebel Maier and Gruppe 2. Their location is unknown. Inside the casemate, Sergeant Cremers, the Belgian commander, observes the glider landings. At 05:30 he orders his gunners to engage the attackers. When the crew attempts to operate the ammunition hoists and rammers, they discover that electrical power has failed. Repairs are attempted under pressure.

Heiner Lange, the glider pilot from Gruppe 5, escorts prisoners toward headquarters. As he passes Cupola 120, the guns swing toward him. Shells from Cupola Sud land nearby and wound him multiple times. Lange orders the prisoners to lie down. He retrieves a 50-kilogram hollow charge from his glider. He places it on the cupola and detonates it. The blast causes no visible damage. A soldier from Trupp 5, Grechza, approaches the position. Having consumed alcohol earlier, he is intoxicated. He climbs onto the gun barrels as they rotate. Oberfeldwebel Wenzel arrives and places a 3-kilogram charge into each barrel. The explosion kills the gunners inside and disables the casemate.

| Multimedia |

| Sturmgruppe Granit, Gruppe 6 and 7, the Northern Cupolas (Objective 14 and 16) |

The northern cupolas are designated Objectives 14 and 16. German intelligence assesses these positions as among the most powerful elements of Fort Eben Emael’s armament. Both are believed to be 120-millimetre artillery cupolas positioned at the northern apex of the fort. Because of their perceived importance, each objective is assigned a full Gruppe from Sturmgruppe Granit.

At the same time, Feldwebel Fritz Heinemann leads Gruppe 7, and Feldwebel Siegfried Harlos leads Gruppe 6. Their objectives are these two northern turret blocs.

The two Gruppen land to the north-east and north-west of Mi Sud. Their landing points place them between approximately one hundred and forty metres and one hundred and sixty metres from their respective objectives. Feldwebel Harlos and Feldwebel Heinemann lead their men forward across the open surface of the fort. Progress is obstructed by extensive barbed-wire entanglements. Bangalore Torpedoes are employed to blast lanes through the wire and permit further advance.

The assault groups then move towards the two northern blocs. Harlos and Heinemann quickly identify the true situation. The armoured turrets in the northern angle of the fort are light metal decoys. The Belgian deception functions as intended. It causes brief confusion. It has no influence on the outcome of the assault.

German intelligence has also identified another cupola, designated Objective 32, located beyond the southern boundary of the fort. This position is likewise a false installation. Either its true nature is recognised in advance or its location is judged beyond the practical reach of the airborne assault. In either case, the position is ignored by the Fallschirmjäger and no attempt is made to attack it.

The two Gruppen then establish defensive positions facing west toward the Geer River.

| Gruppe 8, Cupola Nord (Objective 31) |

The first to land are Oberjäger Karl Unger and Gruppe 8. The glider is piloted by Pilot Diestelmeir. At an altitude of 300 metres, the glider starts circling to lose height. They descend steeply towards the fort under anti-aircraft machine-gun fire. To avoid the fire, he rapidly loses height. Flying low, he swings south and approaches from that direction. It lands at 04:24 hours, 30 metres from Objective 31, Cupola Nord.

Immediately after landing, the pioneers exit the glider at maximum speed. Each man grabs his 25-kilogram explosive load and rushes towards the cupola. Inside Cupola Nord, Sergent Joris observes the landings through the periscope. He sees gliders touching down in the open area to the north. He lowers the retractable cupola into its chamber and reports to the command post that aircraft have landed near Mi Nord (19).

As Diestelmeir’s glider comes to a halt, Belgian troops sheltering in the hangar (25) open fire on Gruppe 8. Being first to land and close to the hangar, Unger’s section draws most of the small-arms fire. Unger, Bruno Hooge, and Ernst Hierlaender exit the glider at once. Feldwebel Meyer is wounded only metres from the glider. Weinert takes cover beside the glider. He deploys the bipod of his MG 34, feeds the 7.92 mm ammunition belt, and returns fire.

Under cover of the machine-gun fire, Gefreiter Else and Gefreiter Pliz dash towards the hangar. As they reach the building, Feldwebel Hauge’s section joins the fight. This section has already secured its own objective at position 29. Else places a conventional 2.5 kilogram charge at the door. The explosion neutralises the defenders inside. Soldat Remy and Soldat Heine are killed. Adjudant Longdoz is wounded. A potentially dangerous Belgian group, led by an officer, is eliminated within minutes.

Meanwhile, Feldwebel Unger, assisted by Hooge and Hierlaender, runs towards Cupola Nord. Inside, Sergent Joris shouts for ammunition. Cupola Nord has not yet received its allocation of boîtes-à-balles ammunition. With such rounds, the turret could have swept the surface at close range. No one expects close combat so early in the action. Had they been ready, the outcome of the attack might have been different. Instead, Soldat Hanot arrives with two high-explosive rounds carried up from the magazine. The rounds are loaded into the breeches. As the crew prepares to raise the cupola, a violent explosion shakes the structure.

From beside his glider, Pilot Diestelmeir observes two men placing a 50-kilogram charge on the cupola. The charge is fused and ignited. The detonation is immense. The ground heaves and throws him into the air. With this blast, Cupola Nord is put out of action.

Obergefreiter Else positions a machine gun to provide covering fire. Inside Cupola Nord, Sergents Kip and Joris man the 75-millimetre guns from 05:30. They report enemy movement on the fort roof. Sergent Joris, the cupola commander, carries antipersonnel ammunition up the stairway when the first heavy charge detonates. No one is inside the turret at that moment. Seeing no external damage, Unger orders another 50-kilogram charge placed near the steel exit. The explosion disables electrical systems and renders the cupola inoperable.

Inside, Sergent Joris experiences the explosion as it penetrates the steel cupola. The blast twists the guns in their mountings. The ammunition mechanism is damaged. Control cables are severed. The cupola is neutralised before firing a single round.

Outside, Feldwebel Unger posts a man to cover the heavy steel door of the infantry sally port. This is the most likely direction of a counter-attack. Unger then places a 12.5-kilogram hollow charge against the door. The explosion rips it from its hinges. Large blocks of concrete collapse into the opening and seal it.

The Belgian defenders do not attempt a counter-attack. They instead bring a machine gun into action. It fires at Fallschirmjäger attacking other structures along the southern edge of the fort. A conventional 2.5 kilogram charge is placed beneath the mount. It fails to silence the weapon.

With the enemy on the Upper Surface and his troops under concrete cover, Major Jottrand requests artillery support from headquarters Position Fortifiée de Liège. As the shells begin to fall, Feldwebel Unger completes his task near Cupola Nord. He sees a signal, likely from Feldwebel Wenzel or one of his men, ordering him to move to Mi Nord. Unger orders his section to disperse into open formation to reduce losses. While crossing scrub on the crest of the Tranchée de Caester, a shell fragment kills Unger. Only Obergefreiter Else and two other Fallschirmjäger reach Wenzel’s command post. Else takes command of Gruppe 8.

Up to this point, Sturmgruppe Granit suffers unusually light casualties. Other sections that breach casemates remain well protected from Belgian fire. They must still leave cover to complete neutralisation tasks or move towards Mi Nord to form a defensive perimeter.

At 05:45, Major Jottrand orders the tunnel sealed and Cupola Nord abandoned. The Belgian crew retreats down the stairway. The airlock doors at the base of the bloc are closed. They are reinforced with steel beams and sandbags. The Germans do not follow the defenders to the lower level.

| Multimedia |

| Gruppe 9, Mi Sud |

Mi Sud is assigned to Gruppe 9 of Sturmgruppe Granit. Gruppe 9 is led by Oberjäger Neuhaus. The DFS 230 assault glider is piloted by Hauptfeldwebel Schultz. The glider faces antiaircraft fire near Maastricht. The glider is shaken but remains airborne. The Glider lands approximately forty-five metres east of the objective. The target is one of two machine-gun casemates whose three embrasures dominate the open upper surface of the fort and pose an immediate threat to Fallschirmjäger operating in the open.

On landing, the men find themselves trapped in barbed wire. The obstacle is cut quickly. Oberjäger Ewald Neuhaus leads the men forward. He cuts through barbed wire to reach the bloc. At first, the position appears abandoned. The Belgian crews of the Mi Sud and Mi Nord casemates are expected to be among the last to come into action. Their weapons are intended for use only after enemy forces advance on the fort from the direction of Maastricht. At the time of the glider landings, the machine-gun crews are tasked with moving documents into the interior of the fort and destroying the external barrack blocks. As a result, both casemates are temporarily unmanned at the critical moment of the airborne assault. This circumstance is not anticipated by German planning and represents a decisive element of chance combined with operational surprise.

Unlike the southern artillery positions and the anti-aircraft emplacements, Mi Sud is protected by extensive barbed-wire entanglements. Feldwebel Neuhaus encounters immediate difficulty while attempting to breach the wire. Fire is received from other Belgian positions on the fort, including initially from the area of the hangar. While cutting through the wire, clothing and equipment become entangled, delaying progress. Men following through the breach carry hollow charges and a flamethrower. Fire from the southern sector intensifies to such an extent that the Fallschirmjäger are temporarily forced into cover on the northern side of the earth bank.

Once resistance from the hangar area is suppressed and Adjudant Longdoz and his men are neutralised, Feldwebel Neuhaus and two soldiers are able to crawl forward around the casemate. By this time, Belgian troops have reoccupied Mi Sud. The south-facing machine gun opens fire. Fallschirmjäger Ernst Schlosser avoids the field of fire and manoeuvres into a position suitable for employing the flamethrower. A jet of dark, smoking flame is directed into the embrasure. The Belgian machine-gun crew is forced to cease fire.

This allows the German pioneers to place a 12.5-kilogram charge is placed against the embrasure of Mi Sud. The fuse is ignited and the men withdraw. The Belgian crew, observing the activity through the sight opening, reacts quickly. The breech of the machine gun is opened. Using a cleaning rod pushed up the barrel, the defenders dislodge the charge. It falls to the ground and detonates with little effect.

Further charges are brought forward. Two additional 12.5-kilogram charges and three 50-kilogram hollowcharges are employed in succession. The south-facing embrasure is destroyed. A 50-kilogram hollow charge is then placed against the observation bell. The detonation penetrates the armour.

The blast opens a man-sized breach. Grenades are thrown into the casemate to ensure it is clear. After only a brief occupation of the position, the Belgian defenders withdraw down to the Intermediate Level. By the time Neuhaus enters the position, several Belgian soldiers are found inside, stunned and left behind during the withdrawal. Neuhaus posts guards to secure the position. He then advances towards his secondary objective at the north end of the fort. Additional turret blocs are believed to be located there.

Feldwebel Neuhaus does not pursue the retreating defenders into the interior of the fort. He blocks the steel sally-port door. Another 50-kilogram hollow charge is emplaced. The explosion tears the door inward and wrenches the frame from the structure. His secondary task is to provide covering fire for the assault elements operating in the northern sector of the fort. His men are positioned in firing points both within the casemate and along the eastern slope. No immediate threat develops from the north.

Neuhaus organises a defensive perimeter. A runner from Gruppe 9 is dispatched to Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig. The report confirms that Mi Sud has been captured and that the group is ready to receive further orders.

| Multimedia |

| Sturmgruppe Granit, Gruppe 10, Visé 1 (Objective 26) |

Feldwebel Hübel and Trupp 10 are designated as the reserve element. Their glider lands without opposition. A runner is dispatched immediately to report their position to platoon headquarters. Oberfeldwebel Wenzel assumes command, as Oberleutnant Witzig is still unaccounted for. Wenzel orders an attack on Visé 1.

Visé 1 is set into the large earth bank on the eastern edge of the fort. The casemate is oriented to engage targets to the south. From this position, the crew has a clear view of events unfolding along the southern edge of the upper surface. The casemate is originally assigned to Feldwebel Max Maier and Gruppe 2 of Sturmgruppe Granit. Because this Gruppe fails to land on the fort, Visé 1 remains untouched during the opening phase of the assault.

At 05:35, the Belgian gun crews inside Visé 1 receive a general order to fire several salvos. Almost immediately, air attacks by Junker 87 aircraft force the gunners down to the Intermediate Level. At the same time, detonations from hollow charges on neighbouring positions blow air-intake valves off the interior fittings of the casemate. The Belgian gunners are unable to counter these effects. Morale inside the casemate deteriorates rapidly.

Feldwebel Hubel and Gruppe 10 land less than 100 metres south of Visé 1. While moving toward Mi Nord, where his Gruppe is intended to join headquarters and become the reserve of Sturmgruppe Granit, the runner returns with the order to attack Visé 1. Hubel immediately turns his attention to the casemate and begins preparations to neutralise it. This position lies in the north-east sector of the fort. It mounts three 75-millimetre guns facing south. Within five minutes, the observation cupola is destroyed.

Throughout this phase of the battle, Junker 87 dive bombers remain on call above Eben Emael. Their presence exerts constant pressure on the Belgian defenders.

After a short interval, the crew returns to their posts. At 06:00, Sous-Lieutenant Desloover and Soldat Delcourt fire several salvos. Shortly thereafter, the officer is recalled to the command post. The crew again evacuates toward the Intermediate Level.

At 06:10, Major Jean Fritz Lucien Jottrand issues an order for general fire intended to occupy the crews. The guns are not directed against the Fallschirmjäger on the surface, as the trajectory of the shells passes over their positions.

The situation at Visé 1 remains confused. At 06:40, the command post prematurely reports to RFL that the casemate has been knocked out by German action. Five minutes later, the unsettled crew transmits a new report. Direct bomb hits are claimed against the casemate. Sounds of German movement are heard on the exterior of the structure.

At 07:00, worsening conditions inside the casemate caused by lack of ventilation force the crew to withdraw once more to the Intermediate Level.

| Sturmgruppe Granit, Gruppe 11 |

As said earlier, Leutnant Rudolf Witzig. Unternehmen Granit’s commander also commands Glider Team 11. The team does not reach Eben-Emael with the task force. After crossing the the River Rhine, the towing rope snap. Having progressed this far, Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig refuses to abandon the operation or allow his men to attack Eben Emael without him. He instructs the glider pilot to cross the river Rhine into Germany and to search for a meadow large enough to permit both landing and a renewed take-off. Once the DFS 230 is on the ground, orders are issued to unload the aircraft. The glider is moved to the edge of the meadow. It is then reloaded. Witzig orders his men to clear hedges and fences. He hopes to create an improvised take-off strip.

During these actions, Witzig sets out to return to Köln-Ostheim. He begins on foot. He then requisitions a bicycle from a railway worker. He subsequently requisitions a motor vehicle from a medical officer. Using this means of transport, he reaches the Luftwaffe headquarters at Köln-Ostheim.

At the airfield, Witzig locates a flight commander familiar with the operational requirements. Acting on his own authority, the officer secures a reserve Junker 52 from General der Flieger Kurt Student. A parachute is issued to Witzig in case landing proves impossible. Preparations are made to resume the mission.

While airborne, Witzig briefs the Junker 52 pilot on the situation. He provides precise instructions for the landing site. At 05:05, Witzig returns with the Junker 52. The pilot lands the aircraft and taxis to the edge of the field where the glider is positioned. The engines remain running. The glider is reattached without delay. Orders are given for the tow flight to proceed toward Aachen. The route follows the same course toward the western German border. The assigned altitude is set at 750 metres. Subsequent events beyond this point are considered secondary to reaching the objective.

The renewed departure takes place under clear morning conditions. The glider is released over German territory. During the flight westwards, Luftwaffe formations are observed heading toward the front. Anti-aircraft fire is visible intermittently as small bursts in the distance. No hits are sustained. The course continues toward Fort Eben Emael, which the pilot navigates without difficulty.

| Sturmgruppe Granit, Gruppe 2 |

Shortly after take-off, the DFS 230 glider of Gruppe 3 commanded by Walter Meier and piloted by Oberjäger Bredenbreck is forced to make an emergency landing near Soller, close to Düren. This occurs about ten minutes into the flight after an evasive manoeuvre to avoid collision with the towing aircraft.

Once on the ground, the occupants consider how they might still reach Fort Eben-Emael overland. A Leutnant of Pionier-Regiment 22 persuades the owners of two civilian vehicles, Adler 2.5-litre cabriolets, to lend them to the Fallschirmjäger. None of the men know how to drive. Their determination nevertheless outweighs all difficulties. With the assistance of two drivers from Organisation Todt, they set off toward their objective. Pilot Oberjäger Bredenbreck remains behind to guard the glider.

The two cars head for Maastricht. The journey proves difficult. Roads are congested with lorries and long columns of German troop transports moving west for the invasion of Belgium and the Netherlands. The group forces its way through. On reaching Maastricht, they cross the River Maas in rubber dinghies alongside the first infantrymen to reach the far bank after the bridges have been destroyed. They then seize a Dutch lorry from a market square and use it to drive the short distance to Kanne on the eastern bank of the Albert Canal.

In effect, Meier’s party becomes the first German troops to make contact with the paratroopers at Kanne. Their sudden appearance comes as a shock to the Belgian defenders, who are preparing to engage the airborne troops landed on the Opkanne heights. Shortly after entering the village, Meier’s Gruppe takes between thirty and forty Belgian soldiers prisoner. They then move toward the Canal, where they encounter a new obstacle. The bridge has been destroyed. This prevents them from reaching the rest of Sturmgruppe Granit, which is fighting less than two kilometres away at Fort Eben-Emael on the western bank.

Fire from Belgian strongpoints D and E, together with the casemates flanking the bridge, sweeps the canal bank where Meier’s men are pinned down. Max Maier is struck in the head by machine-gun fire from the position commanded by Lieutenant Berlaimont and is killed instantly. Fritz Gehlich confirms that nothing can be done to save him. Following this loss, Walter Meier decides to attempt a crossing of the Canal. The waterway is not wide, and debris from the destroyed bridge offers some concealment by breaking up movement in the water.

Meier, known as Pi-Meier because he serves with the pioneers, crosses alone while the rest of Gruppe 2 remains under cover. After reaching the western bank, he proceeds on foot toward Emael. He avoids contact with enemy forces, which proves easier than expected, as his Fallschirmjäger uniform is not immediately recognised. At the entrance to Fort Eben-Emael he finds no guards. He moves on to Block II, roughly 300 metres to the left of the main entrance. On the way he is forced to take cover during a Stuka attack. Block II is also deserted.

Meier intends to return to Kanne and lead his Gruppe across to Fort Eben-Emael. When he reaches the Canal again, he comes under fire from Belgian strongpoints D, E, and C. This deters him from attempting another crossing. He withdraws back to Block II. There he encounters Oberjäger Harlos, commander of Gruppe 6 of Sturmgruppe Granit. Re-establishing contact with his own Gruppe proves impossible. Meier therefore remains under cover and waits for nightfall.

After dark, he returns once more to the western bank of the Canal. Using field glasses, he observes German infantry now occupying the eastern bank. To his astonishment, they open fire on him. They fail to recognise his airborne uniform. Meier attempts to signal that he is German and that he can show them a safe route to the fort. The combination of the destroyed bridge and continued Belgian machine-gun fire prevents the infantry from crossing.

Frustrated, Meier exposes himself to Belgian fire and crosses back to the eastern bank. There he briefs two German infantry Lieutenants on the situation. Despite all complications, relief for the paratroopers is finally imminent. Before the infantry reaches Kanne, the three 88-millimetre batteries of Aldinger’s Abteilung move forward. They take up positions on a hill midway between Fort Sint Pieter, an old Dutch fort south of Maastricht with no strategic value, and the Albert Canal. From there, they improve the accuracy of their fire. These batteries support the attacks on the Canal crossings and provide crucial assistance to Sturmgruppe Granit, which remains cut off and in a critical situation outside Fort Eben-Emael.

At 22:30, the bridgehead established by the paratroopers after a day of intense fighting finally makes contact with Oberstleutnant Mikosch. A hazardous relief operation follows. 6. und 7. Kompanie, II. Bataillon, Infanterie-Regiment 151, reinforced by 2. und 3. Kompanie, Pionier-Bataillon 51, together with a machine-gun platoon, cross the Albert Canal in rubber dinghies. Before this crossing, German troops succeed in silencing machine-gun fire from well-concealed Belgian positions outside Kanne. Another decisive factor is the suppression of Belgian artillery fire. At 03:00, the relieving forces reach the airborne troops and take over their positions.

During these hours, Walter Meier continues his urgent search for the remaining men of his Gruppe at Kanne. He later records that he is unable to find them. An infantry officer has ordered them back to Maastricht after relieving them, in recognition of their actions at Kanne. Meier later learns that Gefreiter Bader alone has taken 121 Belgian prisoners. He does manage to locate Gefreiter Ölmann, who has remained behind. Ölmann appears exhausted and worn down after firing throughout the night toward the western bank of the Canal. Although Ölmann wishes to accompany him, Meier sends him to the dressing station. Meier then returns to Block II. There he finally meets his Gruppenführer, Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig. Shortly afterwards, infantry units arrive and complete the relief of the airborne troops.

In the early hours of May 11th, 1940, additional Fallschirmjäger under Leutnant Meissner cross to the eastern bank of the Canal. The remaining men of Sturmgruppe Eisen are relieved during the morning. Rubber dinghies operate continuously, forming a makeshift ferry. Only wounded men and Belgian prisoners remain to be transported across. By about 15:00, the last Eisen paratroopers leave Kanne and rejoin the other survivors in Maastricht. They spend the night of May 11th, 1940, in a school building.

At around 18:00 on May 12th, 1940, the Fallschirmjäger arrive at the Dellbrück barracks in Cologne. The journey by lorry is repeatedly interrupted. In Maastricht it is halted by a British air raid. Further delays occur en route to Cologne, where roads are clogged with German military traffic moving into Belgium and the Netherlands.

| Multimedia |

| The rest of the day |

Within the first thirty minutes of the assault, all antiaircraft guns and exposed machine-gun positions are destroyed. Mi Nord, Mi Sud, Vise 1, and Cupola Nord are neutralised. Cupola Sud is damaged and continues firing at reduced effectiveness. German troops now move freely across the fort roof.

Feldwebel Wenzel conducts reconnaissance of nearby casemates to determine which remain operational. At the same time, he attempts to locate Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig to report the capture of Mi Nord. Contact is made with the radio operator Gilg, who is also searching for orders to establish communications. No runners succeed in locating Witzig or elements of Gruppe 11. It becomes apparent that Gruppe 11 has not landed on the fort.

With Oberleutnant Witzig absent and Leutnant Delica heavily engaged near Maastricht 2, Feldwebel Wenzel assumes effective command of the northern sector. Familiarity with the operational plan allows him to carry out this role without disruption until Witzig arrives.

A radio position is established at the northern rampart. A dressing station is set up at the same location. Early fighting has already resulted in 2 dead and 12 wounded. Radio contact is made with Sturmgruppe Beton at Vroenhoven, where Hauptmann Walter Koch maintains his command post. A situation report is transmitted. Close air support is requested to suppress approaches to the fort entrances and to prevent Belgian reinforcement from the village of Eben Emael.

Within 20 minutes, Junker 87 dive bombers and Henschel 126 aircraft arrive overhead and conduct precision attacks. A Heinkel 111 bomber passes over the fort and drops containers filled with fresh ammunition.

By 07:30, sixty-two German soldiers hold the roof of Fort Eben Emael. They have been in position for nearly two hours. Two men are dead. Eight are seriously wounded. Four are lightly wounded. Oberleutnant Witzig and Trupp 2 are still missing. All antiaircraft guns and exposed machine guns are destroyed. Mi Nord, Mi Sud, Vise 1, Maastricht 1, Maastricht 2, Cupola 120, and Cupola Nord are neutralised. Cupola Sud continues firing at reduced capacity. The surrounding blockhouses remain inactive.

Leutnant Delica has been coordinating Stuka attacks within forty-five minutes of landing. He also directs two aircraft to deliver ammunition and water. Oberfeldwebel Wenzel remains in command. He maintains radio contact with Hauptmann Koch and reports the situation.

At 08:30, a single glider appears over the Fort and lands near headquarters. Oberleutnant Witzig emerges with Feldwebel Schwarz and reserve Trupp 11. By the time Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig reaches Eben Emael, most of the fort is already in German hands. Fighting on the surface has largely subsided. Fire is sporadic and limited in intensity. Witzig proceeds to Objective 19, the designated command post location. There he reports to Feldwebel Wenzel, who has assumed control of the position in the interim. Wenzel is already receiving situation reports from various assault elements. A functioning command post is established. Essential items, including aerial photographs, call signs, radios, and command material, are assembled to sustain control of the platoon.

Feldwebel Wenzel is an experienced Heeres-Pionier with extensive operational background. At Eben Emael he proves an energetic and capable troop leader. With the surface largely secured, Sturmgruppe Granit has two remaining tasks. The first is to breach the fortified entrances in order to carry the attack into the interior of the fortress. The second is to hold all captured positions until relief forces arrive.