| Page Created |

| December 24th, 2025 |

| Last Updated |

| February 6th, 2026 |

| Germany |

|

| Related Pages |

| Fall Gelb DFS 230, Lastensegelflugzeug Fort d’Ében-Émael Preperations Unternehmen Danzig Fall Gelb, The Maastricht Gateway Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Beton Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Eisen Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Granit Unternehmen Danzig, Sturmgruppe Stahl |

| Unternehmen Danzig, May 10th, 1940 |

| Podcast |

| Objectives |

- Seize the Prins Albert Kanaal bridges at Veldwezelt, Vroenhoven, and Canne.

- Neutralise the artillery positions at Fort Eben Emael.

- Hold a bridgehead on the Eastern side of the river until relieved.

| Operational Area |

| Axis Forces |

- Sturmabteilung Koch

- Sturmgruppe Beton

- Sturmgruppe Eisen

- Sturmgruppe Granit

- Sturmgruppe Stahl

- 17. Staffel, Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 5

- Flak-Sondereinheit „Aldinger“

- 1./Flak-Abteilung 6

- 3./Flak-Abteilung 64

- Trude-Suchscheinwerfer- und Baken-Einheit

- Gallert-Suchscheinwerfer- und Baken-Einheit

| Preparations Unternehmen Danzig |

On October 9th, 1939, operational planning for a campaign in the west begins. This follows the issue of Weisung Nr. 6 für die Kriegsführung. The directive initiates preparations for offensive operations against Western Europe. Almost two weeks later, on October 21st, 1939, Adolf Hitler adds a decisive idea to the initial planning. He proposes that the Belgian Fort Eben Emael be seized by assault groups landing in transport gliders. He also envisages parachute troops being dropped on the bridges over the Maas and the Albert Canal.

General der Flieger Kurt Student travels to Berlin for consultations. During the discussion that follows, the Führer Adolf Hitler sets out his views on airborne warfare. Student later recalls the exchange clearly. Student’s own doctrine on the employment of the Fallschirmjäger is soon to be tested in practice.

Hitler explains his ideas with clear-sighted lucidity and persuasive force. Student is astonished by Hitler’s grasp of this new form of warfare. He is particularly struck by Hitler’s understanding of glider operations. Hitler stresses that airborne troops represent a completely new and untried weapon. He emphasises that, for Germany, this arm remains secret. He states that the first airborne operation must employ every available resource. It must be delivered boldly at a decisive time and place. For this reason, Hitler explains, he has refrained from using airborne forces until suitable objectives present themselves.

Hitler has already ordered planning for the war in the West to begin. He asks whether Student’s gliders and paratroopers can capture Eben Emael. He proposes a landing on the large grassy field on top of the fort. He envisages an immediate assault on the fortifications. The rapid breakthrough of the 6. Armee between Roermond and Liège depends on capturing the bridges over the Albert Canal intact. To achieve this, Eben Emael must first be neutralised. His views are shaped by experiences and accounts from the First World War. He recounts the capture of Fort Douaumont during the fighting at Verdun.

Fort Douaumont is recaptured by French Colonial troops on October 24th, 1916. German forces withdraw before the assault takes place. There is no major combat inside the fort during the recapture. The French attack follows an extensive preliminary bombardment. Nearly 4,000 heavy-calibre shells are fired in preparation. These include 300 shells of 370 millimetres and 100 shells of 400 millimetres. Railway artillery delivers the largest rounds. The bombardment devastates the external structures of the fort. The surrounding ground is reduced to a cratered landscape. Between September 1914 and November 1917, more than 120,000 shells strike Douaumont. Over 2,000 of these exceed 270 millimetres. French losses during repeated recapture efforts are estimated at more than 100,000 men. Hitler believes such losses must be avoided in future operations. He is convinced that gliders combined with hollow charges provide an alternative. He shows particular enthusiasm for sudden and unexpected assaults. His attention turns to Fort Eben Emael.

General der Flieger Student replies that he is uncertain. He states that he requires time to consider the proposal. Hitler reacts sharply to this hesitation. He orders Student to leave, reflect overnight, and return the next morning. When Student returns the following day, he states that the operation appears possible. He adds a condition. The landings must take place in daylight. Hitler agrees to this requirement.

Hitler then surprises Student again. He reveals the development of a new explosive device. The charge weighs 50 kilogram. Hitler claims it can penetrate any known steel or reinforced concrete fortification. The weapon is known as a Hohlladung, or hollow charge. Hitler assures Student that this device will guarantee success. He then issues his instructions concerning the forthcoming offensive.

Hitler orders that the 7. Flieger-Division and the 22. Luftlande-Division, under Generalmajor Kurt Student, are to seize the Reduit National. This chain of fortifications runs along the Belgian border. The divisions are to hold this line until the arrival of the mechanised columns of the Wehrmacht.

Hitler further orders that parachute troops and glider-borne forces are to carry out surprise attacks. These attacks are directed against Eben Emael, the bridges over the Albert Canal to the north, and the Meuse bridges near Maastricht. The purpose is to facilitate the rapid crossing of the Maas and the Albert Canal by the 6. Armee.

It is essential to land directly on the fort and attack the artillery positions that protect the river and canal crossings. This action is intended to convince the French and British commands that the German main effort lies in the north. The attack must appear to follow the pattern of 1914 by advancing through Belgium. This deception succeeds. Allied commanders accept that Germany is repeating its First World War strategy.

To reinforce this impression, the 6. Armee must strike into Belgium without delay. It must drive as far west as possible. The enemy is expected to conclude that Germany is advancing as before. This assumption forces Allied forces to move forward rapidly. Their concentration in the north then creates the conditions required elsewhere.

Once this reaction is achieved, the armoured groups in the south can attack. Their advance initiates the Sichelschnitt plan. In operational terms, this deception forms the true purpose of the operation. Within forty-eight hours of the meeting, operational orders are issued to neutralise the fort. The operation is assigned the code name Unternehmen Granite.

Operational planning soon confirms that a specially trained force is necessary. Both Hitler and Student rule out a parachute assault. The Junker 52 transport aircraft carries only twelve Fallschirmjäger. These troops are lightly armed and carry limited demolition equipment. A standard parachute drop occupies several minutes per aircraft. The descent disperses troops across an area of roughly 275 metres. Additional equipment must be dropped separately in containers. Soldiers must locate and retrieve this equipment after landing. This creates delays at a critical moment. The operation demands exact placement of troops on the fort roof. Cupolas, casemates, and combat blocks must be neutralised immediately. This must occur before Belgian defenders can demolish the nearby bridges. Parachute forces cannot deliver the required precision. The DFS 230 glider offers a viable solution. It carries ten men together with heavy equipment. The total load does not exceed approximately 2,090 kilograms. The glider is capable of landing silently within about 18 metres of the intended landing point.

| Multimedia |

| Sturmabteilung Koch |

On November 2nd, 1939, Generalmajor Student selects Hauptmann S. A. Koch for the mission. Koch commands Kompanie 1, Fliegerjäger Regiment 1, within the 7. Flieger-Division. He is respected as an imaginative officer with strong tactical insight. The company is reinforced by a pioneer platoon from 7. Flieger-Division. This platoon is led by Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig. These two units form the nucleus of a new assault unit.

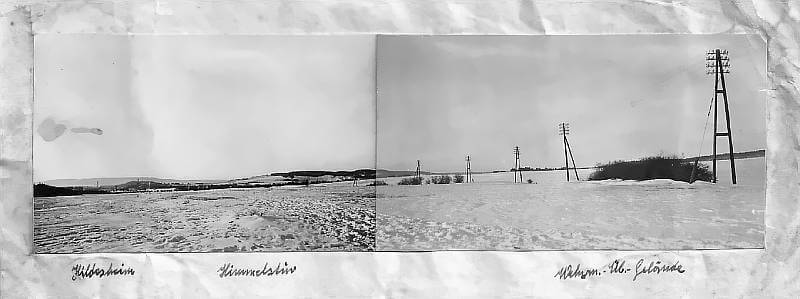

The unit is renamed Sturmabteilung Koch. That very same day, Hauptmann Walther Koch receives orders from his battalion commander, Major Erich Walther. He is instructed to transfer to Hildesheim and prepare the mission. The first Fallschirmjäger arrive soon after. They include four officers, forty-one non-commissioned officers, and 145 enlisted men. Witzig’s pioneer platoon arrives the following day.

This pioneer platoon is unique within the German airborne arm. It originates from Army volunteers integrated into airborne units in 1937. Initially formed as a company, it later expands to battalion size. In October 1939, one month before Sturmabteilung Koch is established, the platoon is separated from II. Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 1. It becomes directly subordinate to 7. Flieger-Division.

In early November 1939, Koch is informed that his unit falls under the direct authority of General von Reichenau. During the forthcoming invasion of Belgium and France, it will operate as part of 6. Armee. Alongside the Fallschirmjäger at Hildesheim, three searchlight detachments are assigned. Their task is to illuminate the flight corridor across Germany to the Dutch border. This allows Junker 52 towing aircraft to navigate accurately at night. A glider detachment is also attached and an airfield operations company. For operational employment, a towing formation with Junker 52 aircraft is assigned.

Oberleutnant Hassinger of the Pionier-Lehr-Bataillon is attached to instruct the Fallschirmjäger in engineering tasks. Major Reeps assumes responsibility for glider transport. Thirty railway wagons are allocated for this purpose. All movement occurs under strict secrecy. Oberleutnant Walter Kieß commands the glider pilot element. This formation is designated Lastensegler-Versuchszug.

That very same month, the first dismantled transport gliders arrive at the two Cologne airfields. They are intended for the strictly secret operation of Sturmabteilung Koch. The gliders are of the type DFS 230, produced by the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug. They are transported overland from Hildesheim in three columns. The transport uses sixty lorries. The fuselages are carried in furniture vans. The wings are moved separately on vehicles covered with tarpaulins.

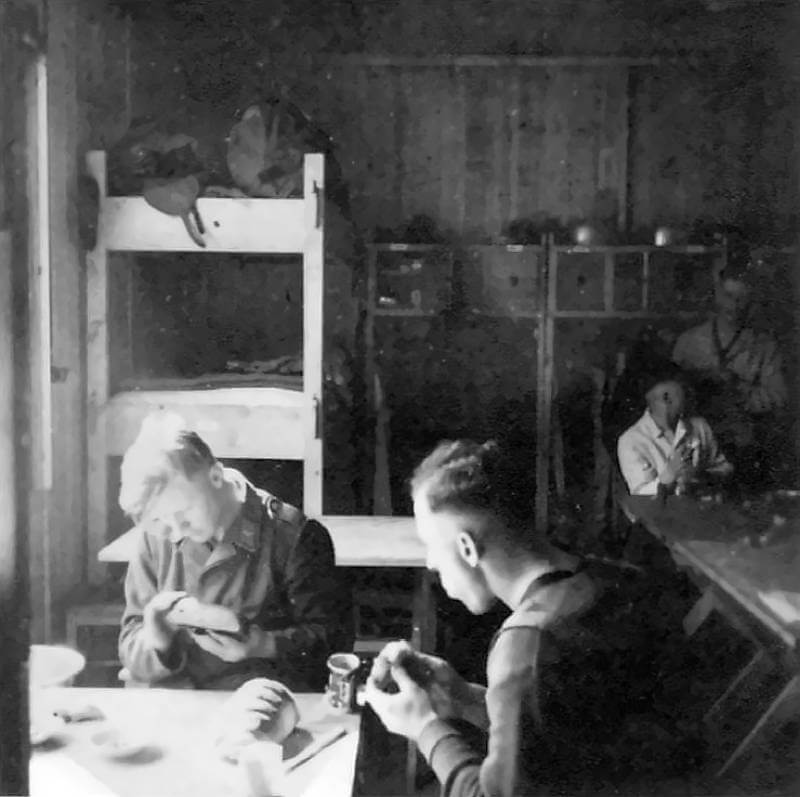

Secrecy measures are enforced rigorously. On November 3rd, 1939, the day Sturmabteilung Koch formally comes into existence, communication restrictions are imposed. Letters and telephone calls are prohibited. Personnel are confined to barracks.

Efforts are made to conceal that the formation includes Fallschirmjäger. No badges or insignia identifying Fallschirmjäger are permitted. Radio equipment is installed and cables are laid. This creates the impression that the unit is training in communications. No man is allowed to know the final objectives before training ends. Every member of Sturmabteilung Koch signs a secrecy declaration under threat of death.

From the outset, many practical issues remain unresolved. One urgent problem is the transport of Fallschirmjäger by glider. Oberleutnant Walter Kieß focuses on securing the best personnel and equipment. He ensures that technical difficulties do not delay the mission. During early November 1939 at Hildesheim, he assembles many of Germany’s most experienced glider pilots.

From November 4th, 1939, systematic testing of the DFS 230 begins. Pilots conduct flights with heavy loads. Night flying is practised. Formation flying is introduced. Precision landings within twenty metres of a target are rehearsed repeatedly. Training also familiarises Fallschirmjäger with the confined interior of the glider. Weapons and equipment must be stowed efficiently. After landing, glider pilots are expected to fight as infantry. They therefore receive training in ground combat and weapons handling.

Training for the pioneer element also begins on November 4th, 1939. Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig’s pioneers train under Oberleutnant Hassinger of the Heer. They work with fifteen hollow charges of 50 kilograms and twenty-five hollow charges of 12.5 kilograms. Other Fallschirmjäger train with hand grenades, smoke charges, 12.5-kilogram mines, limpet mines, and flamethrowers.

| Multimedia |

The relieve of Unternehmen Danzig falls within the responsibility of the 6. Armee. German Generaloberst Walther von Reichenau’s 6. Armee views the Maas crossings at Maastricht, together with the Albert Canal, as the “Maastricht Gateway” into Belgium. At the heart of this concept lies the Albert Canal line north of Eben-Emael. Von Reichenau regards the capture of Fort Eben-Emael as a prerequisite before committing his main concentration of forces. This is the sector where he intends to rupture the Belgian line and then roll up the enemy through fast-moving, expanding operations.

Von Reichenau understands the danger of delay. Every hour that the Albert Canal remains uncrossed weakens surprise and erodes momentum. The psychological shock on the defender diminishes steadily with time.

Adolf Hitler shares this concern. He expects that failure to secure Eben-Emael and the bridges will halt the panzer spearheads. Infantry divisions, he believes, will then be drawn into prolonged and costly battles to force the canal defences. The Eben-Emael sector therefore becomes the cork in the bottle, threatening the entire German strategy by giving the Allies time to organise and consolidate in central Belgium.

The opening attack of 6. Armee is to be launched between Venlo and Aachen. A leading operational echelon of four corps advances with ten infantry divisions. XXVII. Armeekorps, comprising 299. Infanterie-Division and 263. Infanterie-Division, is tasked with attacking the Dutch border fortifications east of Maastricht.

At the same time, an independent advance guard operates under the direct command of 6. Armee. This force consists of the reinforced 4. Panzer-Division. Its mission is to push ahead rapidly and force the Maas crossings in the centre of Maastricht.

Maastricht, in the southern Netherlands, lies on the river Maas at a key crossing point. For that reason, the three main bridges in the city become primary objectives in the German invasion plan: the Sint Servaasbrug, the Wilhelminabrug, and the railway bridge to the north. The plan, developed with Adolf Hitler’s direct involvement, calls for a coup de main against these crossings. The intention is to seize them intact before the Dutch can demolish them. 4. Panzer-Division, with more than 340 tanks, is intended to break through Maastricht into Belgium. For this purpose, undamaged bridges are considered essential.

The seizure of the Maastricht bridges is directly linked to the assault on the Belgian fortress of Eben-Emael. The fortress lies only a few kilometres south-west of Maastricht. It is regarded as a major Belgian strongpoint. It dominates large sections of the Albert Canal, the Maas, and the four nearby bridges. If Eben-Emael remains operational, 4. Panzer-Division risks becoming trapped in a dangerous situation.

This strategic reality drives the Germans towards an integrated plan.

Sturmgruppe Granit is to land by glider directly on to Eben-Emael. Their task is destroying the heavy fortifications of the fort. At the three bridges over the Albert Kanaal, small task forces, also largely Fallschirmjäger, land by glider, and are reinforced later by parachute troops. These lightly equipped units land in a sector defended by a Belgian division. They also face more than 1,000 men inside the fortress itself.

To reinforce these airborne forces quickly, the Germans require an immediate ground route. A secure crossing base on the Albert Canal depends on rapid reinforcement. For that reason, the intact capture of the Maastricht bridges is treated as imperative.

German intelligence on Maastricht is extensive. The Germans know the Dutch bridge security measures. They know the guard routines. They know the demolition instructions. They know the precise locations of the explosive charges. This intelligence is gathered by numerous agents, including Dutch collaborators and German operatives. Maastricht also contains many German residents.

The German assault plan for the Maastricht bridges is structured in three stages. It relies on speed, deception, and surprise, and is designed to capture the crossings before the Dutch can destroy them.

Stage 1 begins before the invasion, when German agents infiltrate Maastricht in civilian clothing. The men are part of Infanterie-Bataillon z.b.V. 100.

Infanterie-Bataillon z.b.V. 100 is formed by the German Abwehr in October 1939 for special missions. The battalion consists of four companies. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd companies are Pionierkompanien. The 4th company is a heavy company. It includes two Panzerabwehrkanone platoons and two schweres Maschinengewehr platoons. The battalion is regarded as a Sturmbataillon. However, it is equipped and organised as a Pionierbataillon. Its total strength is about 550 men. The commander is Hauptmann Fleck.

These men disguise themselves as ordinary Dutch civilians. One commando group consists of seven men, including one German Unteroffizier and six Dutch collaborators. They assemble in the Wijk suburb of Maastricht on May 9th, 1940. At sunrise on May 10th, 1940, they are to attack the Dutch guards at the Wilhelminabrug and prevent demolition.

A second infiltration group consists of thirty men in civilian clothing. Three groups of ten men cross the border on the evening of May 9th, 1940, near Herzogenrath. They collect bicycles stored for them at Bleierheide. They also retrieve weapons previously hidden at Kerkrade. They then move towards the other two bridges in Maastricht.

Their mission is to identify the Dutch demolition charges on the bridges. Before H-Hour, they carry out covert reconnaissance of the bridges and guard patterns. At the moment of attack, they are to remove the explosives or disable the fuses. The intention is to prevent the destruction of the bridges during the assault.

These advance teams are supported by a second unit in Phase 2. Sonderverband Hocke is commanded by Leutnant Hans-Joachim Hocke. It consists of men also selected from Infanterie-Bataillon z.b.V. 100.

Sonderverband Hocke is to cross the Dutch border about 21 kilometres north-east of Maastricht, near Sittard, at 03:20 on May 10th, 1940. The men move in small groups along different routes. They wear Dutch Marechaussee uniforms and travel by motorcycle with sidecars and in armoured cars. Their task is to bluff their way on to the bridges at dawn. They are also to disable demolitions if the advance teams have failed. If the advance teams have succeeded, they are to seize the bridges and hold them until the forces from Phase 3 arrive. They are followed by the rest of Infanterie-Bataillon z.b.V. 100 for secondary support at the start of Fall Gelb.

Phase 3 is the conventional assault by 4. Panzer-Division. Because major water obstacles lie along its axis of advance, the division is equipped with substantial engineer mobility resources, including rubber boats and bridging equipment.

A second operational echelon is scheduled to follow. Comprising I. Armeekorps and XVI. Armeekorps, it is committed late on day one and into day two, and is intended to drive the breakout into Belgium.

Within XVI. Armeekorps, 3. Panzer-Division and 29. Infanterie-Division (motorisiert) are designated as the leading formations. They are supported by the slower infantry divisions of I. Armeekorps, including 11. Infanterie-Division and 61. Infanterie-Division. A further reserve of five fresh infantry divisions is also available.

The army is supported by the Luftwaffe. VIII. Fliegerkorps, commanded by General der Flieger Wolfram von Richthofen, provides offensive air support, while 2. Flak-Korps under General der Flakartillerie Hubert Desloch supplies air defence. Stuka dive-bombers are integrated for close support, with anti-aircraft guns and fighter patrols providing protection against enemy aircraft.

This integrated assault plan unifies the separate attack schemes into a single master operation, designed to force the crossings of the river Maas and the Albert Canal and open the gateway into Belgium.

| Multimedia |

| Sturmabteilung Koch’s Assault Plan |

On November 6th, 1939, Koch and Kieß receive written battle orders. These are delivered personally by General Kurt Student and General Paulus, Chief of Staff of 6. Armee. The orders direct the seizure of the bridges at Maastricht and along the Albert Canal. The bridges are to be kept intact. Consideration is given to destroying bridge demolition systems by precision Stuka strikes. This idea is eventually abandoned. Sturmabteilung Koch must seize the bridges at Veldwezelt, Vroenhoven, and Kanne. It must prevent their demolition. It must also neutralise the artillery positions at Fort Eben Emael. Fort Eben Emael is to be captured. Armoured cupolas and heavy weapons are to be destroyed by explosives.

Bridge assault groups are to neutralise bunkers guarding the crossings. A bridgehead is to be established immediately. Enemy counterattacks are to be repelled. For each bridge, two assault elements are planned. Each consists of four or five squads. The first element attacks bunkers with hollow charges. The second secures a defensive perimeter of approximately 300 metres from the western bridgehead. All objectives must be achieved within thirty minutes. Bridgehead consolidation follows immediately. After ninety minutes, German artillery provides covering fire. Four hours after landing, relief forces are expected to arrive. These requirements necessitate subdivision of the force.

On November 8th, 1939, Koch finalises the organisation. After completing his mission analysis, Hauptmann Koch identifies four critical tasks. These tasks must be completed for Unternehmen Danzig to succeed and to enable the advance of General Fedor von Bock’s Heeresgruppe B and the 4. Panzer-Division.

Five groups are formed. These consist of Witzig’s pioneers and four assault groups. In this plan one Sturmgruppe is assigned to seize the Wilhelmina Bridge at Maastricht. Oberleutnant Altmann commands Sturmgruppe Veldwezelt. He is tasked with the capture of the Veldwezelt Bridge. He is assigned around ninety men and ten gliders. Oberleutnant Schacht leads the assault on the bridge at Vroenhoven. His force consists of about one hundred men and eleven gliders. Hauptmann Koch chooses to position himself near this bridge. Its central location and strong construction make it suitable for command and control. The bridge at Kanne is assigned to Leutnant Schächter. His detachment includes eighty men transported in nine gliders. The assault on Fort Eben Emael, is entrusted to Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig. He commands an engineer platoon of eighty-six men. Oberleutnant Kiess is responsible for glider maintenance and pilot training. Each Sturmgruppe includes one anti-tank gun, one flamethrower, one pioneer section, four light machine-gun teams, and three rifle groups.

As preparations continue, available gliders and Junker 52 towing aircraft increase in number. At Gardelegen, twenty-five non-commissioned officers and 101 men form four ground support groups. These are commanded by Hauptmann Eisenkrämer. By November 9th, 1939, Koch controls thirty-five Junker 52 aircraft and forty-five DFS 230 gliders. The airfield at Mönchengladbach is prepared for flight and landing exercises. A detachment under Leutnant Schacht is earmarked for deployment there.

Plans are made to billet troops at the Dellbrück barracks. General Paulus intervenes. He orders that no man may leave Hildesheim without his express permission.

For the assault on Fort Eben Emael, Witzig identifies three essential tasks. He orders them by priority. First, weapons on the fort roof must be destroyed. These weapons could interfere with glider landings and movement across the surface. Second, gun batteries covering the three bridges must be silenced. Third, entrances and exits must be destroyed to prevent a garrison counterattack. Witzig understands that speed and shock are decisive. He estimates that his platoon has no more than one hour before a Belgian counterattack overwhelms it. Time is critical.

A Luftwaffe liaison officer, Leutnant Delica, is therefore attached to the platoon. Delica serves as both forward air controller and communications officer. He is responsible for calling in bombers and fighters when required. He also controls the planned aerial resupply drop. These measures are intended to defeat Belgian garrison counterattacks. The operational plan includes a link-up with the leading elements of the 4. Panzer-Division. This link-up occurs after the division crosses the Albert Canal. The Pionier-Bataillon 51, part of Infanterie-Regiment 151, is tasked to cross at the Kanne Bridge. If required, it is to relieve the assault force and assist in silencing Fort Eben Emael.

In response to assigned tasks, Oberleutnant Witzig, commander of the assault group to attack Fort Eben Emael, implements specialised training. Pioneer instruction focuses on flamethrowers and hollow charges. Each course is led by a technical specialist. Meanwhile, Koch’s assault troops continue refining attack drills.

Oberleutnant Witzig divides his engineer platoon into eleven sections. Each section is assigned to a single glider. Every section receives the task of destroying two enemy emplacements. Each is also instructed to assume another section’s mission if required. The organisation and assignments are detailed in the planning documents. Each section consists of seven to eight men. Weapons vary by section and include machine guns and flamethrowers. The assault force carries twenty-eight hollow charges weighing 50 kilograms each. It also carries twenty-eight hollow charges weighing 12.5 kilograms each. Additional explosives are included. The total explosive load amounts to approximately two and a half tonnes.

The principle of the hollow charge is first identified in 1888. It is developed by Charles Munroe during experiments on explosive effects. The hollow charge functions by shaping the explosive force. Upon detonation, it produces a concentrated jet of extreme pressure. This jet provides exceptional penetration with a relatively small explosive mass. The pressure generated can blast an opening about 30 centimetres wide. It is lethal to personnel inside enclosed positions. Once detonated, the explosion melts the steel liner of the charge. A stream of molten metal, hot gases, and fragments is driven through a narrow opening into the target. The larger 50-kilogram charge is capable of penetrating up to 25 centimetres of armour or concrete. It is issued in two hemispherical sections and must be assembled before use. The smaller 12.5-kilogram charge consists of a single unit. It is capable of penetrating up to 15 centimetres.

Training intensity remains extreme. Fallschirmjäger conduct route marches of up to fifty kilometres. They carry full equipment loads. They train with explosive charges fitted with ten-second delay fuzes. They learn to interpret aerial photographs and detailed maps. While Fallschirmjäger master a wide range of combat skills, glider pilots focus on flying techniques. Precision landings are refined continuously. Formation and night flying at 140 kilometres per hour becomes routine.

| Multimedia |

| Intelligence |

From November 1939 onward, the Abwehr compiles comprehensive reports on the security measures and control systems at the three key bridges, Veldwezelt, Vroenhoven, Kanne, the Fort Eben Emael and their surrounding terrain. Par example, German soldiers, disguised as Belgian police, conduct reconnaissance of the Albert Canal bridges. The precision with which German agents identify Belgian obstacles and defensive works is remarkable. Their reports include detailed sketches and descriptions. On November 12th, 1939, Hauptmann Walther Koch travels to Münster together with Oberstleutnant Schmidt of the Abwehr and Gruppenführer Heckel to coordinate the intelligence collection efforts in Belgium.

The unit’s name changes repeatedly to mislead outsiders. On November 14th, 1939, it becomes Versuchsabteilung Friedrichshafen. Later designations include Flughafen-Bauzug and 17. Reservestaffel.

Facilities at Cologne airfields used by the unit are also disguised. Hangars are given innocuous names such as Silberfuchsfarm and Pelztierfarm. These measures are intended to deceive other airfield personnel. Security is enforced without compromise.

On November 16th, 1939, General Student conducts his first inspection of Sturmabteilung Koch. At this stage, the strength of the Fallschirmjäger elements continues to increase. The number of searchlight units also expands.

From November 17th, 1939, on security lifts a bit as censored letters and postcards are permitted.

Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr, meets with Hauptmann Walther Koch and General Student on November 18th, 1939. Hauptmann Fleck, Special Commissioner for Sabotage from Bataillon zbV 100, also attends. Fleck raises concerns about capturing the Maastricht bridges. He notes that failure there could affect operations at Veldwezelt and Vroenhoven. Doubts are expressed about a surprise glider assault by Fallschirmjäger. A proposal is made to use precision Stuka attacks to sever detonator cables on the bridges. Fallschirmjäger would then complete the seizure. This proposal is rejected. The original plan is approved with one modification. The Maastricht bridges are assigned exclusively to Bataillon zbV 100.

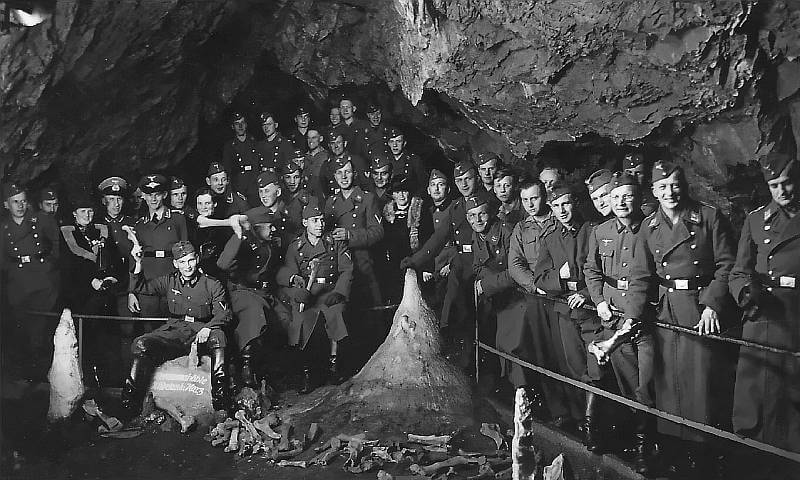

The first tactical trials take place on November 24th, 1939, at Haguenau. Before this, Witzig’s pioneers receive theoretical instruction at the Karlshorst Academy. Training focuses on the use of hollow charges. Practical exercises follow at the former Polish fortifications at Gleiwitz. The hollow charges of 12.5-kilograms and 50-kilograms are employed. Other elements of Sturmabteilung Koch also reach sufficient readiness. By mid-December, commanders decide to test the units under realistic conditions.

From November 20th, 1939, on every new arrival signs a formal undertaking. The declaration states that any breach of secrecy, deliberate or negligent, will be punished by death. This includes oral, written, or pictorial disclosure of service location or objectives. As time passes, restrictions ease slightly.

From November 21st, 1939, limited leave is granted, but only within Hildesheim. Men may not go out alone. Each group is accompanied by a non-commissioned officer. Popular establishments include the Wiener Café, Theatergarten, Korso, and Trocadero. Organised excursions also take place, including visits to the Harz caves.

By December 1939, Sturmabteilung Koch search light units expand. By that time, the unit controls seven platoons of Thurd and Gallert searchlight and beacon units.

From December 14th, 1939, Schächter’s troops train for five days in the Harz region. At the same time, Witzig’s pioneers spend eight days at the fortifications of Tarnowitz and Beuthen in Silesia. These positions closely resemble Fort Eben Emael. The exercises focus on assault methods, demolition techniques, and coordination under confined conditions.

The schwere Maschinengewehr-Halbzug is added to the plan on December 29th, 1939, on General Student’s orders. The core consists of the Maschinengewehr-Zug of 4./Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 1 under Leutnant Ringler. It expands to seventy-two men under his command, supervised by Oberstleutnant Koch. Ringler arrives at Hildesheim with Oberfeldwebel Nollau and Oberfeldwebel Sprengart. They plan the drops using terrain models and training begins immediately.

Following the Mechelen incident, the operational plan for the invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium, and France is revised. The new date for the attack is set for January 17th, 1940.

Hauptmann Koch is summoned to a conference with General Felmy on January 6th, 1940. Felmy commands Luftflotte 2. Koch briefs him on the mission in detail. Koch recognises the urgency of final preparations. Particular emphasis is placed on transferring forces to Cologne airfields. These airfields are designated as the departure points for Belgium. All leave is cancelled until after January 13th, 1940.

After the January false alarm, the Fallschirmjäger continue their preparations. Training now includes air-to-ground communications. Officers from the assault groups and commanders of the fighter units use this pause to coordinate their tasks. They seek closer cooperation for the coming operation. Recognition of ground signals is practised from an altitude of 900 metres.

Major Reeps’s detachment rejoins Sturmabteilung Koch. It assumes responsibility for transporting and assembling the gliders. Three lorry convoys are formed for this task. They are commanded by Oberleutnant Drosson. Reeps also receives responsibility for recovering the gliders after the operation. This measure aims to conceal their existence and use.

The transfer encounters difficulties. Severe cold and ice halt the second convoy. It is forced to turn back. The convoy resumes its movement fourteen hours later. Despite these delays, Reeps and the gliders arrive in Cologne on schedule. At Köln-Ostheim, nineteen gliders are assembled. At Köln-Butzweilerhof, eleven gliders are assembled. A total of sixty lorries are required to transport the components.

On January 9th, 1940, restricted sections of the operating airfields at Butzweilerhof and Ostheim receive cover names. Butzweilerhof is designated Silberfuchsfarm. Ostheim is designated Pelztierfarm. A contemporary witness also reports the Butzweilerhof area being referred to as Hühnerfarm. This sector consists of barracks screened from public view by a high, opaque fence.

Extreme weather also delays Hauptmann Eisenkrämer. Koch therefore requests additional ground personnel from Luftflotte 2. These reserves arrive on January 10th, 1940. They are led by Hauptmann, Pioniertruppe, Dreyer.

The commander of the Fallschirmjäger Vorkommando Butzweilerhof and the soldiers of the detachment are quartered in the Göring-Kaserne at Köln-Dellbrück. At Köln-Butzweilerhof airfield, eleven transport gliders are unloaded. At Köln-Ostheim, a further nineteen transport gliders are unloaded. Under the highest level of secrecy, the lorries are emptied. Personnel of the Fallschirmjäger Vorkommando move the components into hangars secured by barbed wire and electric fencing. Assembly begins immediately. One soldier observes furniture vans arriving at night on the Butzweilerhof without lights.

At Butzweilerhof, assembly takes place in Hangar I. The hangar is only partially completed at this time. It lies within the old airfield area. Even personnel of the airfield command are denied access. Only the numerous sentries patrolling around the hangar are visible.

During the winter and spring of 1940, DFS 230 transport gliders are present at Köln-Ostheim airfield. These aircraft are intended for the planned assault against the Belgian fortress Eben Emael. Security regulations surrounding the operation are extremely strict. The forthcoming Fallschirmjäger glider landings in Belgium are treated as top secret.

In February 1940, Sturmabteilung Koch undergoes reorganisation. On February 5th, 1940, a number of pilots are detached. They move under Hauptmann Arnold Willerding to Braunschweig-Waggum. Their task is to establish a Luftwaffe glider training school. Oberleutnant Walter Kieß loses twenty glider pilots. Eight Ju 52 crews and six flying instructors are also transferred. In total, two officers, forty-one non-commissioned officers, and seventeen men leave the unit. This represents a serious disruption to Koch’s planning.

For security reasons, Kieß’s command is renamed at the end of January. It now carries the designation 17. Staffel, Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 5 (17./KGzbV 5). Further changes affect the company of Oberleutnant Gustav Altmann. The most significant concerns the bridge at Kanne. The original assault group is dissolved. Its personnel are distributed among the remaining groups as reinforcements. Training in demolition techniques is expanded. It now applies to all of 1. Kompanie and to Witzig’s pioneers.

| Multimedia |

| Fire Support |

Fire support is essential for securing the bridgeheads. The Fallschirmjäger require artillery support from the outset. On February 13th, 1940, the idea of an anti-tank company of Fallschirmjäger is proposed. No unit is available. The final solution is support by the Aldinger Flak unit. It consists of three batteries with four 88-millimetre guns each. A further three batteries each field twelve 20-millimetre guns.

Because of his experience in Spain, Aldinger is selected to support Sturmabteilung Koch. His task is to reduce Belgian pressure on the bridgeheads. His three batteries advance along the eastern bank of the Meuse toward Maastricht. They provide rapid and effective artillery support to the Fallschirmjäger operations.

To coordinate fires, joint exercises are conducted. These focus mainly on communications. Detailed maps are prepared. They show numbered aiming points for Aldinger’s guns. Each assault group reports by radio to Koch’s command post. They specify which aiming point requires fire. Accurate target identification is essential. Each assault group therefore includes an artillery observer.

Aldinger’s 1./Flak-Abteilung 6 supports the Stahl and Beton groups. Batterie 3./Flak-Abteilung 64 supports the Eisen group at Kanne. Oberleutnant Rausch of the Abwehr in Cologne supplies Koch with Belgian radio frequencies. These are used by Belgian units for internal communications. This intelligence greatly assists the German operation. It enables effective monitoring and jamming of enemy radio traffic.

Oberjäger Rudolf Urban is appointed non-commissioned officer responsible for communications within Sturmabteilung Koch. Code names are assigned for security. Veldwezelt is Stahl. Vroenhoven is Beton. Kanne is Eisen. Fort Eben-Emael is Granit. Aldinger’s command post is Donner. The forward observer is Bruno. Batterie 1 is Berta. Batterie 2 is Siegrid. Batterie 3 is Hilde. Pionier-Bataillon 51 of the Heer and an attached Panzer unit operate under the code name Oberon. Koch’s command post at Vroenhoven and the headquarters of VIII. Fliegerkorps, the Aldinger group, and 4. Panzer-Division also receive separate cover names.

Oberleutnant Altmann assumes the role of coordinator for the Sturmabteilung Koch units. This includes responsibility for personnel management. The task proves demanding. Koch reportedly remarks that Rhinelanders should not be recruited. Koch himself is a Rhinelander. His main concern remains the frequent changes to the attack plan.

| Specialist Training |

In February 1940, the Pioneer platoon deploys to former Czechoslovakia. It later moves into Poland. Training there focuses on breaching casemates and cupolas. The men practise capturing fortified positions. These structures once defend against a German advance. The Benes Line stretches for roughly 480 kilometres. It is equipped with modern weapons from leading Czech manufacturers. Physical conditioning follows tactical requirements. Training emphasises climbing and rapid movement under full load. This approach mirrors modern battle-focused conditioning. On February 27th, 1940, a new restriction is imposed. All rank and branch insignia are banned. Uniform jackets must remain completely plain.

Witzig expands the programme further. Pilots are integrated into the assault sections. They train alongside infantry and engineers. In time, they are capable of operating all platoon weapons. Training areas are constructed to scale. Aerial reconnaissance photographs guide their layout. Distances and proportions match the real objectives. Platoon members attend specialist demolition courses. Their focus is the destruction of Belgian artillery and anti-aircraft positions. They also study fort construction methods. This knowledge is gained through discussions with engineers and civilian contractors.

On February 29th, 1940, objective recognition starts. The Fallschirmjäger see aerial photographs of the bridges and Fort Eben Emael for the first time. That same month, the concept shifts again. The operation is to begin with Stuka attacks. Gliders carrying Fallschirmjäger are to follow. This removes the element of surprise. It also risks heavy losses in the opening phase.

The capture of the Kanne bridge is declared essential at any cost. However, German planners cannot increase the number of gliders assigned to the objective. Severe congestion at Cologne-Ostheim airfield prevents additional take-offs. The only workable solution is to dispatch the ten gliders allocated to Group Eisen from Cologne-Butzweilerhof.

Besides that, operational conditions make an accurate landing near the bridge impossible. The gliders are instead directed toward the heights of Opkanne. This area consists of three distinct ridges, identified as North Hill, Central Hill, and South Hill. These hills rise on the western bank of the Albert Canal. German commanders fully understand the inherent weakness of this plan. The intended landing areas lie too far from the Canal. Any landing there inevitably alerts Belgian defenders. This creates a serious risk that the bridge will be destroyed before seizure. Despite this, confidence remains intact. Morale among the Fallschirmjager does not falter. From Koch downward, all ranks believe success remains achievable. The operation relies on speed, shock, and aggressive action.

However, on March 1st, 1940, Koch proposes a revised plan. On March 4th, 1940, the revised assault plan for the bridges and Fort Eben Emael is presented at a conference. Present are Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring, Generalmajor Student, Generalleutnant Graf Sponeck, Hauptmann Koch, and Oberleutnant Witzig. The immediate cause is the reinforcement of Belgian troops in the sector. Within Sturmabteilung Koch, the unit previously assigned to Kanne is dissolved. The extreme difficulty of the objective and the requirement to reinforce the attacks on Veldwezelt and Vroenhoven lead to its redistribution. Koch also rejects the use of air bombardment against those two bridges before the gliders arrive. He insists that Luftwaffe intervention begin no earlier than fifteen minutes after landing. Aircraft from VIII. Fliegerkorps are tasked with protection and close support only after this interval.

Although the original Kanne assault group ceases to exist, the Führer orders a new force to be raised. It consists of ninety Heer pioneers. These men are trained and commanded by officers from Sturmabteilung Koch. This arrangement reduces the operational burden on 7. Flieger-Division. On May 10th, 1940, that formation commits its full strength to operations in Belgium and the Netherlands. The newly formed Kanne force is further strengthened by the addition of a heavy machine-gun half-platoon. Comparable reinforcements are also assigned to the bridge assaults at Veldwezelt and Vroenhoven. General Student authorises this decision.

These adjustments again reshape the operational concept along the Albert Canal. The Kanne bridge is no longer treated as an independent objective. Its capture now depends on success at Fort Eben Emael by Rudolf Witzig’s detachment. Control of Kanne provides a secure crossing point. It enables the rapid withdrawal of Surmgruppe Granit from the fort and of the bridge detachments to the north. It also allows Wehrmacht units assigned to unite the four objectives to cross the Canal at this location.

Following this meeting, Koch and Witzig submit a detailed report to Adolf Hitler. It covers training and planning for operations in Belgium and the Netherlands. Hitler approves Koch’s proposal. He assigns ninety additional men from an Army pioneer battalion. All are volunteers from 6. Armee. They have already distinguished themselves during the Polish campaign. This group forms the core of a new assault element. It is placed under Leutnant Martin Schächter. Its task is the attack on the bridge at Kanne. The first men arrive at Hildesheim on March 11th, 1940. The new pioneers, however, have little time to prepare. This lack of preparation later contributes to difficulties during the assault. Most of Sturmabteilung Koch already has months of training by this point.

From March 1940, emphasis shifts to detailed target analysis. Every objective is studied closely. Sources include aerial photographs, Belgian deserters of German origin, agents, and even postage stamps. On March 2nd, 1940, Erwin Ziller constructs a scale model of Fort Eben Emael. On March 23rd, 1940, he builds models of the Vroenhoven bridge and surrounding terrain. He also models the bridge at Kanne.

Koch’s men study every detail. They practise on bridges near Hildesheim. Sniper training begins on March 4th, 1940. Explosive placement is rehearsed using mortar shell casings. Training also includes paddling rubber assault boats. Training with the MP 38 machine pistol becomes routine by that time. By the end of March, training reaches completion. Sturmabteilung Koch now functions as a cohesive and highly effective combat unit.

Four Belgian deserters from Eupen–Malmedy join the Fallschirmjäger on March 14th, 1940. All four have served in the Belgian Army and have been stationed on the Albert Canal bridges. Their local knowledge later proves highly valuable to Sturmabteilung Koch. The background to this lies in the region of Eupen and Malmedy, which borders Germany. This area remains German territory until 1925, when it is transferred to Belgium under Article 34 of the Treaty of Versailles. For many inhabitants of German origin, loyalty to the Belgian state and King Leopold proves problematic.

On March 26th, 1940, it is decided that three schwere MG-Halbzugs will jump forty-five minutes after the attack. All operate under Leutnant Helmut Ringler. Transport responsibility lies with I./KG zbV 172. The unit supports the bridgeheads at Veldwezelt, Vroenhoven, and Kanne.

At the end of March, cover names are formally assigned. Stahl designates Veldwezelt. Beton designates Vroenhoven. Eisen designates Kanne. These names also apply to the departure airfields. The chosen airfields are Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof. Two sites are required. No single airfield can launch all Ju 52 towing aircraft and gliders within a twenty-five-minute window.

Weeks before the western campaign begins, additional DFS 230 gliders arrive at Ostheim. They are delivered packed in crates. Transport takes place by rail to the Kalk Nord freight yard. From there, the Deutsche Reichsbahn moves the wagons onward.

The railway wagons are loaded onto Culemeyer road rollers. These street transporters move the wagons at night without lights to the airfield. The journey follows the Olpener Straße. Sections of this route are very narrow. This makes the transport of heavy low-loaders carrying full rail wagons particularly difficult.

Herr Weiß accompanies these transports in his civilian capacity. He observes the movement of the wagons from the freight yard to the airfield. The deliveries take place discreetly to avoid attention.

These gliders represent individual replacement deliveries. They do not form the main shipment. The bulk of the DFS 230 gliders has already arrived in Cologne by road between January 9th and January 11th, 1940.

Flight training continues without interruption. By March 1940, pilots can operate at night. They fly in small groups of two or three gliders. Landings take place at unknown airfields. Accuracy improves to within five to nine metres of the intended point. That very same month, Assault Force Granite completes two full rehearsals. These include glider launches, landings, and assaults against replica targets.

Two aspects of the operation remain untested. A full-scale launch involving the entire Sturmabteilung Koch is never rehearsed. The hollow charge is also excluded from training. Its existence is treated as highly classified. Hitler orders that it must not be exposed. The device is also under development for other strategic programmes. Only Oberleutnant Witzig witnesses a live detonation before the mission. As May 1940 approaches, the men wait for the assault order. The operation carries the code name Danzig.

On April 1st, 1940, Hauptmann Koch inspects the operational airfields at Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof. He also inspects the Scheinwerferzug Thurm. On April 8th, 1940, communications trials are conducted. These aim to improve coordination between the Fallschirmjäger, Aldinger’s Flak, and Luftwaffe air units. From April 9th, 1940, on steel helmets for the Fallschirmjäger are repainted at the operational airfields. The work takes place at Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof. A new camouflage colour is applied. Helmet camouflage is repeatedly revised. The final pattern is issued on April 23rd, 1940.

One day later, on April 10th, 1940, Hauptmann Koch travels to Schloss Dyck near Grevenbroich. He meets the commander of VIII. Fliegerkorps, Generalleutnant Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen. The meeting serves as an operational briefing. Afterward, Koch returns to inspect the forward-deployed elements. He visits Köln-Ostheim, Köln-Butzweilerhof, and the Scheinwerferzug Thurm. That very same day, the plan for the supporting MG-Halbzug under Leutnant Ringler is finalised. Practical training moves exclusively to Köln-Ostheim.

The parachute dummies arrive on April 11th, 1940, at Fliegerhorst Köln-Ostheim. They are delivered for use by Sturmabteilung Koch. These dummies are intended for deception and training purposes.

Startleiter Major Reeps relocates with his command on April 13th, 1940. He moves from Fliegerhorst Köln-Ostheim to Flugplatz Köln-Butzweilerhof. This relocation supports the upcoming operation scheduled for May 9th to May 10th, 1940. On the same day, Leutnant Krüger assumes the role of Startleiter at Köln-Ostheim.

Oberleutnant Zierach, the Operations Officer (Ia) of Sturmabteilung Koch, inspects the forward-deployed elements on April 14th, 1940. He visits both Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof. He coordinates supply arrangements. He also organises accommodation for the Fallschirmjäger. These matters are settled through discussions with the local commanders at both airfields.

At Fliegerhorst Köln-Ostheim, parts of the hangar apron and one aircraft hangar are sealed with barbed wire. Within this restricted area, Fallschirmjäger of Sturmabteilung Koch are quartered. These troops receive specialised training for operations using transport gliders.

Security dominates every phase of preparation. Surprise is essential for success. The timing of the assault must remain unknown. Even limited resistance on the fort roof could halt the attack. General Student later emphasises that secrecy is absolute. From the moment orders are issued, only five officers know the target’s identity and location. The unit adopts a new designation whenever it relocates. Titles include Airport Construction Platoon and Experimental Section Friedrichshafen. Gliders are dismantled after training. They are moved using civilian furniture vans. Storage takes place in guarded hangars. Perimeters are concealed behind fencing covered with straw mats.

All correspondence is strictly controlled. Letters are reviewed by Oberleutnant Witzig, Hauptmann Koch, or Oberleutnant Kieß. Soldiers are removed from public view. Contact with civilians and other units is avoided. Sergeant Helmut Wenzl later recalls the restrictions. The men may attend cinemas but only under guard. Insignia are removed. Names are not used. When contact occurs with known civilians, the entire unit is relocated immediately. Each man signs a declaration acknowledging the penalty for disclosure. The stated punishment is death. Enforcement is uncompromising. Two Luftwaffe soldiers approaching the hangar before the operation are detained. They remain in custody until the mission concludes. Two assault troops are discovered speaking with another unit. They are scheduled for execution. The assault order arrives before the sentence is carried out. Both men are released and take part in the attack.

On April 18th, 1940, Sturmabteilung Koch numbers thirty-three officers and 1,127 other ranks. Ground personnel include eleven officers and 427 men. Forty-two glider pilots are present, with four held in reserve. The flying personnel include eleven officers and 182 men. Among them are forty-two Junker 52 pilots. One reserve pilot is available. Six Junkers pilots are assigned to transport the heavy machine-gun half-platoon.

On April 21st, 1940, the Fallschirmjäger command under Hauptmann Koch conducts a demonstration attack. The exercise takes place on the Wahner Heide. Senior Luftwaffe officers observe the operation. Flak units support the assault. Sturzkampfflugzeuge provide air support. The target is a heavily defended strongpoint.

Final preparations focus on coordination. Junker 52 transport aircraft and fighter formations must operate seamlessly with the ground assault. Other details are refined.

Training continues at Hildesheim. On April 21st, 1940, fifty Junker 52 aircraft embark all Fallschirmjäger designated for the operation. The exercise tests coordination between Fallschirmjäger, Sturzkampfverbände, and Flak. The scenario involves an assault on a heavily defended objective.

On April 22nd and April 25th, 1940, a large-scale exercise follows. All sectors participate. Participants include Fallschirmjäger radio operators, commanders, and artillery observers. A reconnaissance Panzer and a radio detachment from Pionier-Bataillon 51 are present. Aldinger’s radio troop also participates. Radio operators from VIII. Fliegerkorps take part. Earlier in April, Unternehmen Weserübung is executed. The invasion of Denmark and Norway achieves relative success. Following this, Major Reeps’s detachment rejoins Sturmabteilung Koch. It occupies quarters at Köln-Ostheim airfield.

On April 30th, 1940, another large exercise takes place near Einbeck. Fighter aircraft participate. 3. Staffel simulates an attack on I./Infanterie-Regiment 132. Fallschirmjäger conduct a successful drop.

On May 1st, 1940, Witzig’s pioneers relocate to Hilden near Düsseldorf. One day later, on May 2nd, 1940, final operational discussions take place at the Führer headquarters. Present are Generalmajor Student, Generalleutnant Graf Sponeck, and Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring. Generalleutnant Graf Sponeck commands 22. Luftlande-Division, which is assigned a major role in the invasion of the Netherlands. Reichsmarschall Göring is not invited.

The principal issue concerns the timing of the attack. Glider pilots are capable of flying in darkness. Landing in darkness remains hazardous. It is therefore decided that glider landings will take place at first light. The attack is scheduled for 05.35. This is twenty minutes before sunrise.

On May 5th, 1940, Hauptmann Koch, arrives at Köln-Butzweilerhof airfield. He attends a commanders’ conference led by Generalleutnant Wolfram von Richthofen. Hauptmann Koch meets General Wolfram von Richthofen of VIII. Fliegerkorps and Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring of Luftflotte 2. Kesselring has recently replaced General Felmy. The discussion again centres on coordination between ground forces and airborne troops. It is agreed that all Luftflotte 2 aircraft will operate under Kesselring’s overall command during the attack. During this meeting, final and binding coordination is established.

The transport of the Fallschirmjäger is assigned to Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 1. The Geschwader is commanded by Generalmajor Hans-Georg von Morzik. Forty-two Junker 52 towing aircraft from 17. Staffel/Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 5 are allocated. These aircraft are divided into four operational groups. Four additional Junker 52 remain on reserve. Six further Junker 52 are assigned to carry Fallschirmjäger scheduled to jump after the initial bridge assaults begin. On April 26th, 1940, the detailed composition of the towing Staffeln is announced.

From Köln-Ostheim, the Staffel assigned to Granit operates against Fort Eben Emael. It consists of eleven Junker 52 aircraft. The Staffel is commanded by Leutnant Schweizer, with Leutnant Jahnke as deputy. Also from Köln-Ostheim, the Beton Staffel is assigned to Vroenhoven. It consists of ten Junker 52 aircraft under Leutnant Seide, with Leutnant Davignon as deputy. A third Staffel from Köln-Ostheim is assigned to Stahl at Veldwezelt. It consists of nine Junker 52 aircraft commanded by Oberleutnant Nevries, with Oberjäger Zimmermann as deputy.

From Köln-Butzweilerhof, the Eisen Staffel is tasked with the attack on Kanne. It consists of ten Ju 52 aircraft under Oberleutnant Steinweg, with Oberleutnant Rigel as deputy. Also based at Butzweilerhof is a special Staffel from I./Kampfgeschwader zur Besonderen Verwendung. It operates six Ju 52 aircraft. These carry Ringler’s heavy machine-gun half-platoon.

Because two additional Fallschirmjäger squads are added shortly before the operation, Beton receives one extra Junker 52 and DFS 230 glider. A further aircraft and glider are also allocated to Stahl. This additional aircraft is scheduled to depart from Butzweilerhof.

Five Heinkel He 111 bombers of I./Kampfgeschwader 4 are assigned for resupply. They take off from Köln-Butzweilerhof. They drop ammunition and supplies in two waves. The first drop occurs approximately forty-five minutes after the landing. The second follows around one hundred and sixty minutes later. Drops are made from an altitude of between 200 and 300 metres.

Each bridge assault group is to receive sixteen supply containers. Assaultgruppe Granit at Fort Eben Emael is to receive thirty-two containers. Four Dornier Do 17 bombers and six Henschel Hs 126 reconnaissance aircraft provide air cover over the Fallschirmjäger. Over Belgium itself, responsibility rests with VIII. Fliegerkorps under General von Richthofen. This formation specialises in close air support. It includes Stuka units, Henschel Hs 123 aircraft, and Messerschmitt Bf 109E fighters.

The aircraft of VIII. Fliegerkorps support the attacks against the fortified belt around Liège. They then support the advance inland. Fifteen minutes after the initial landings, they begin providing direct support to the Fallschirmjäger from the rear. Once the airborne objectives are secured, their task shifts to escorting the German ground advance into France.

Adolf Hitler had initially designated May 7th, 1940, as the start of Fall Gelb. After a delay of two days, he sets the final date as May 10th, 1940. On May 7th, 1940, three road convoys move the gliders to the airfields. These convoys are led by Major Reeps, Oberjäger Sticken, and Leutnant Krüger. These aircraft serve as reinforcement.

On May 8th, 1940, additional troops join Sturmabteilung Koch. Assaultgruppen Stahl and Beton each receive one additional squad. The final strength of the glider-borne assault groups is now fixed. Stahl at Veldwezelt consists of one officer and ninety-one men. Beton at Vroenhoven consists of five officers and one hundred and twenty-nine men. Eisen at Kanne consists of two officers and eighty-eight men. Granit at Fort Eben Emael consists of two officers and eighty-three men.

| Multimedia |

| May 9th, 1940 |

At 13.00 General Student receives the codeword Rumänien. Fall Gelb is confirmed as May 10th, 1940. During the afternoon, Sturmabteilung Koch redeploys from Hildesheim to Cologne. This movement is ordered by VIII. Fliegerkorps. For camouflage purposes, the entire formation operates under the cover designation Staffel / Kampfgeschwader zur besonderen Verwendung 5 or Versuchsabteilung Friedrichshafen.

Between 18.00 and 18.30, major air movements take place. Eleven Junkers Junker 52/3m aircraft of I. Gruppe, Luftlandegeschwader 1, land at Köln-Butzweilerhof. They carry Fallschirmjäger of Sturmgruppe Eisen and Sturmgruppe Stahl. At the same time, thirty-one Junkers Junker 52/3m of the same formation land at Köln-Ostheim. These aircraft transport Fallschirmjäger of Sturmgruppe Beton and the remainder of Sturmgruppe Stahl. The official designation Luftlandegeschwader is applied only after the operation.

Hauptmann Koch, lands at Köln-Ostheim. He arrives aboard a Junker 52/3m flown by Unteroffizier Otto Krutsch. At approximately 18.30, Sturmgruppe Granit arrives at Köln-Ostheim by lorry. This group consists of eighty-five Fallschirmjäger from the Fallschirm-Pionierzug. They travel from Hilden, departing from the Flakkaserne. This unit had previously been stationed at Köln-Ostheim weeks earlier. It then moves to Köln-Dellbrück and later to Hilden. These movements serve deception purposes.

Immediately after landing, all Ju 52 aircraft are refuelled at both Cologne airfields. The Flughafenbetriebskompanie under Hauptmann Eisenkrämer directs the aircraft to their assigned positions. At 20.00, Hauptmann Koch arrives at Köln-Butzweilerhof. He is accompanied by Oberleutnant Kieß, commander of the Lastenseglerkommando. Together they inspect the aircraft, the assembled Fallschirmjäger of the assault groups, the schwere Maschinengewehr-Zug under Leutnant Ringler, and the Startkommando under Major Reeps.

From 20.00 onward, the transport gliders stored in hangars since January are brought out. Assembly and positioning take place at both airfields. During this period, I. Gruppe Sturzkampfgeschwader 76 under Hauptmann Sigel redeploys to Köln-Ostheim. The unit is subordinated to Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 Immelmann. At the same time, II. Gruppe Zerstörergeschwader 76, known as the Haifisch-Gruppe, arrives at Flugplatz Wahn. The group is equipped with Messerschmitt Bf 110 aircraft. Its commander is Hauptmann Groth. Additional Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters land at Wahn.

At 21.00, the code word Danzig confirms the final execution order. Instructions are issued throughout the formations. The attack in the West is now set to begin.

| Multimedia |

| Glidersupport |

In October 1939, the Luftwaffe decides to create a transport unit for airborne operations in Belgium. Its task is to deliver paratroopers to objectives along the Albert Canal. The unit consists of glider pilots under the command of Oberleutnant Walter Kieß. For security reasons, it receives the cover name Propaganda-Ballonzug. The unit is based at Hildesheim.

The initial establishment includes one officer, twenty-nine men, and fifteen aircraft. These consist of eleven Ju 52 transports and four gliders. Immediate efforts focus on recalling former trainees from the first and second glider pilot courses. Most of these men return to their original units or civilian occupations after completing training. One example is Feldwebel Hans Hempel. After finishing the second training course, he returns to Kampfgeschwader General Wever. In September 1939, he is posted to the Stabstaffel of Kampfgeschwader 3.

Tracing these men proves difficult. At least two years have passed since their training. Their experience with the DFS 230 makes them especially valuable. In some cases, their commanding officers refuse to release them temporarily for service with Sturmabteilung Koch. To accelerate formation of the unit, a decision is taken to recruit competition glider pilots. Both military and civilian pilots are accepted. Additional instructors with DFS 230 experience are also required. Many new pilots have never seen an assault glider before.

Experienced instructors from the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug are summoned. These include Rudi Opitz, Heinz Schubert, and Ludwig Egner. They are ordered to join Sturmabteilung Koch. Refusal is not an option.

At Hildesheim, Opitz encounters around twenty former trainees. These include Bredenbeck, Bösebeck, Distelmeier, Flucke, Hempel, Kieß, Krusewitz, Lehmann, Noske, Oeltjen, Raschke, Schedalke, Scheidhauer, Schweigmann, Staubach, Stern, Stoffel, Stuhr, Supper, and Wienberg.

Many civilian pilots already hold prizes and distinctions. Several work as instructors at gliding schools. Among them is Otto Bräutigam, a former Olympic competitor. He sets a world gliding record and wins the Adolf Hitler Prize in 1939. Erwin Ziller, another world record holder, wins the same prize that year. Other well-known pilots include Erwin Kraft, Wilhelm Fulda, and Heiner Lange.

Because the operation may begin at any moment, training begins immediately. New pilots are introduced to the DFS 230 without delay. Veteran glider pilots from the experimental glider platoon provide instruction. Experienced pilots often fly the DFS 230 alone on their first sortie. Less experienced pilots are accompanied by veterans.

| Multimedia |

| Tow Pilots |

Tow pilots are recruited in parallel. Most selected tow pilots are highly experienced. Most are born between 1912 and 1915. All complete advanced navigation training at a Flugzeugführerschule C. Each also attends a Blindfliegerschule. There they receive further instruction in instrument flying and dead reckoning. After qualification, these pilots rank among the Luftwaffe’s most specialised aircrew.

Tow pilots also experience long periods without flying. November proves particularly inactive. When not flying, glider pilots remain confined to their barracks. They must sign out whenever they leave. Tow pilots, glider pilots, and Fallschirmjäger are housed separately. Contact between groups is prohibited. Meals are taken at fixed times. Pilots are forbidden to sit with or speak to members of other groups.

Relations between tow pilots and glider pilots remain strained. Hillebrand rarely flies with the same glider pilot twice. Opitz recalls widespread dissatisfaction. The glider pilots do not know the purpose of their training. Some prefer to fly other aircraft. Information is deliberately limited. Training scenarios are drawn in sand tables. No objectives or locations are named.

Tow pilots, trained in instrument flying, remain aloof. They expect long-range navigation duties. Towing gliders frustrates them. Fallschirmjäger prefer parachute descents to riding in fragile gliders of wood, aluminium, and canvas.

The are some tensions between civilian glider pilots and military veterans. Civilian pilots receive low ranks. Many veterans hold senior non-commissioned ranks. Military pilots lack experience in soaring flight. Civilian pilots bring skills gained only through sport gliding in variable winds.

| Training |

On November 20th, 1939, Pilz conducts a thirty-five-minute flight of unknown purpose. This likely forms part of Propaganda-Ballonzug trials. Tests examine multiple towing methods. These include three gliders behind one aircraft. Another method uses two gliders with tow cables of eighty and one hundred twenty metres. None proves suitable for mass take-off operations.

Doubts also exist at senior levels. The General Staff questions whether Eben Emael and the Albert Canal bridges can be captured from the air. The original plan relies on bombing and artillery fire. This fire is to cease shortly before glider landings. Civilian pilots such as Opitz, Egner, and Schubert judge this extremely dangerous. Poor timing risks friendly fire. They discuss alternatives privately. They prefer a surprise night attack in formation. Kurt Student proposes this option on December 5th, 1939.

Several experimental flights are conducted at varying altitudes. On December 12th, 1939, Heiner Lange flies at 2,500 metres. Several pilots of Sturmabteilung Koch later state that some flights reach 4,500 metres. At that height the temperature is reported as minus eight degrees Celsius. These claims cannot be confirmed.

During Christmas leave, civilian pilots visit Dr. Jacobs. He oversees development of the DFS 230. They express concerns about daylight landings. Jacobs contacts Hanna Reitsch. She is the department’s test pilot. She enjoys the confidence of Adolf Hitler and senior Luftwaffe officers, including Generaloberst Udet. The recipients of her intervention remain unknown. After the holidays, orders require one civilian glider pilot to report to General Ritter von Greim. He is tasked with investigating the complaint during a visit to Hildesheim.

To conceal the identity of the original complainant, the pilots select Flieger Otto Bräutigam. He presents their alternative plan. Hanna Reitsch later describes Bräutigam as confident, courageous, and humorous. She notes his bitterness at the treatment of glider pilots. She emphasises that these men are neither cowards nor undisciplined. They refuse to accept errors that risk lives solely due to rank. Reitsch supports their stance indirectly.

A practical test follows. A bridge and bunker near Hildesheim are selected. Otto Bräutigam and Oberleutnant Walter Kieß fly the trial. Both are released at night several kilometres from the objective. They navigate without assistance. Kieß misses his target by over one kilometre. Bräutigam lands within a few metres. The test proves a night landing is feasible.

In January 1940, glider pilots undertake test flights over unfamiliar terrain. The purpose is to identify potential landing zones. Meadows marked with bright colours serve as reference points.

Encouraged by the potential of the DFS 230, the Luftwaffe decides in January 1940 to establish a glider training school. The location is Braunschweig-Waggum. The aim is to train additional glider and tow pilots. Hauptmann Arnold Willerding becomes the first commandant. The school begins operations on February 5, 1940. Its initial strength includes eight Junker 52 aircraft, twenty DFS 230 gliders, and six instructors.

Several Ju 52 aircraft and DFS 230 gliders are transferred from Propaganda-Ballonzug. Pilots are also detached. Oberfeldwebel Alfred Hillebrand participates in these transfers. He ferries three gliders from Hildesheim between February 16th and February 18th, 1940. February 16th, 1940marks the beginning of pilot training at Braunschweig. Instructors assigned include Rudi Opitz, Heiner Lange, Hans Distelmeier, Erwin Kraft, Erich Mayer, and Wilhelm Fulda.

At the same time, the assault plan against Eben Emael and the Albert Canal bridges is revised. The number of participating troops increases. Additional glider pilots are required. The new school at Braunschweig becomes essential. Training activity there contrasts sharply with Hildesheim. At Braunschweig, flying occurs continuously. Each instructor is assigned several students. Training flights rotate throughout the day. Night flying is also included.

On the nights of January 6th and January 7th, 1940, several pilots, including Lange and Pilz, conduct short night flights around Hildesheim. These are the only night flights before May 10th, 1940. After successful trials on January 11th, 1940, command decides the assault will begin at dawn.

Eyewitness accounts differ on night training. Some pilots receive instruction based on skill level. Others, including Opitz and Egner, never fly at night before May 10th, 1940. During one experimental flight, a pilot becomes lost. Lacking height to return, he lands inside an Army barracks. The sentries are completely surprised. The incident demonstrates that small airborne forces can land inside defended positions.

To maintain correct night formation, Ju 52 aircraft are fitted with eight formation lights on the rudder. Metal shielding hides the lights if a glider climbs too high. Additional shielding prevents detection from the ground.

During that same period, Fritz Stammer proposes a rigid coupling system between towing aircraft and glider. This system offers greater stability than the seventy-metre flexible tow rope. There is insufficient time for technical development and pilot training. The concept is therefore not adopted.

| Multimedia |

| Recruitment |

Recruitment remains discreet. Candidates receive personal invitations. Many are recent Luftwaffe recruits. Each candidate is assumed to hold at least a civilian C-level glider qualification. After approximately four weeks of intensive training, students are deemed capable of flying the DFS 230. They are then replaced by a new intake.

The school also retrains pilots newly assigned to Propaganda-Ballonzug. This includes former trainees from earlier courses. Pilots such as Gerken, Nagel, Schupp, and Winkler refresh their DFS 230 skills.

On May 9th, 1940, Rudi Opitz and the other instructors at Braunschweig receive immediate orders. They are to report to Cologne. Opitz flies there aboard a Junker 52. This aircraft later tows a glider during the attack. Unteroffizier Otto Krutsch also receives orders. He is an experienced powered-aircraft pilot. He completes instrument training at Blindflugschule Wien-Aspern. In March 1940 he transfers to Braunschweig to train as a tow pilot. On May 3rd, 1940, he is ordered to report to Hildesheim with a Ju 52. On May 9th, 1940, he flies Hauptmann Koch to Cologne-Ostheim.

At the Cologne airfields of Ostheim and Butzweilerhof, preparations are complete. Glider start positions are marked on the grass strips. The DFS 230 gliders and most pilots remain inside hangars until darkness. When Rudi Opitz arrives on the evening of May 9th, 1940, he is shown his assigned glider. He receives no briefing on the plan or target until late at night. He is told only that his task is to deliver the assault force. Once landed, responsibility passes to the troops. Most glider pilots have the same experience.

| Multimedia |

| May 10th, 1940 |

During the night of May 9th to May 10th, 1940, Major Reeps and his men conduct all start preparations at Köln-Butzweilerhof. Major Reeps serves as Startleiter of Sturmabteilung Koch. He is responsible for the complete launch process of the Ju 52 and DFS 230 towing formations.

His duties include refuelling the Junker 52 aircraft. He oversees precise positioning at designated starting points. Identification boards mark the exact location for each aircraft. The DFS 230 gliders are rolled out of the hangars. They are positioned behind the towing aircraft at marked points. Tow cables are inspected and connected. Undercarriages are checked. Cable tension is verified. Final start signals are given to each aircraft chain.

All work is conducted in complete darkness. Only hand torches are permitted. These conditions significantly complicate the preparations. Despite this, the start sequence proceeds in an orderly and controlled manner.

After 05.00, two operations commence from Köln-Butzweilerhof. The first operation heads for the bridge at Veldwezelt. One towing formation of the 3. Schleppstaffel departs. It carries one Schleppzug of Sturmgruppe Stahl. Commander of the Fallschirmjäger is Oberleutnant Altmann. Commander of the Schleppstaffel is Oberleutnant Nevries. The second objective from Köln-Butzweilerhof flies towards the bridge at Kanne. The 4. Schleppstaffel departs with ten Schleppzüge of Sturmgruppe Eisen. Commander of the Fallschirmjäger is Oberleutnant Schächter. Commander of the Schleppstaffel liegt bei Oberleutnant Steinweg.

Three operations also commence from Köln-Ostheim. The bridge at Veldwezelt is again the objective of 3. Schleppstaffel with nine Schleppzüge of Sturmgruppe Stahl. Commander of the Fallschirmjäger is Oberleutnant Altmann. Commander of the Schleppstaffel is Oberleutnant Nevries.

The bridge at Vroenhoven is the next operation. The 2. Schleppstaffel departs with eleven Schleppzüge of Sturmgruppe Beton. Commander of the Fallschirmjäger is Leutnant Schacht. Commander of the Schleppstaffel is Leutnant Seide.

Fort Eben-Emael is the final objective. The 1. Schleppstaffel departs with eleven Schleppzüge of Sturmgruppe Granit. Commander of the Fallschirmjäger is Oberleutnant Witzig. Commander of the Schleppstaffel is Leutnant Schweitzer. The eleven Junker 52/3m aircraft of the 1. Schleppstaffel, mission consists of towing the 1. Lastenseglerstaffel of Sturmgruppe Granit and dropping parachute dummies.

Overall command of the glider formations lies with Oberleutnant Walter Kieß. He serves as Führer des Lastenseglerkommandos.

The towing aircraft belong to I. and II./Luftlandegeschwader 1 and bear the Kennzeichen 4H+. The towing aircraft and DFS 230 gliders are organised in groups of three. At intervals of roughly twenty seconds, a light signal authorises the next group to take off. Each group flies in a characteristic V-chain formation. One glider occupies the central position. This aircraft leads the formation.

Each Junker 52 towing aircraft carries a row of eight small lights beneath the tailplane. These lights are set into a V-shaped metal shield. The shield faces rearwards. From the ground the lights are invisible. From the glider cockpit they are clearly visible. They allow the glider pilot to maintain correct heading and height. The pilot simply ensures that the lights remain in view. If the lights disappear, the glider has climbed too high or dropped too low relative to the towing aircraft.

Up to the Dutch border, the aircraft are guided by 50-centimetre searchlights and moving beams operated by the units under Lieutenants Thurm and Gallert. These lights are active continuously between 04:30 and 05:40. The beacons remain constantly illuminated, while the searchlights are switched off for ten seconds in every forty. All beams are inclined at an angle of forty-five degrees to the east.

The first beacon is positioned eleven kilometres from the take-off point at the Efferen crossing. The final marker, a searchlight with a fixed beam, stands on the Vetschauer Berg, north-west of Aachen-Laurensberg. Over Aachen the individual aircraft begin to separate, each following the lights for at least two marked stretches. There were probably four beacon zones in total. One for each objective. The Beacon zones consisted of several searchlights with an objective specific light configuration.

The beacon zones form the disengagement point from the towing aircraft. They lay on the German side of the Dutch border. Release is intended to take place at an altitude of 2,600 metres, but not all towing combinations reach this height in time. As a result, several Junker 52 pilots have little choice but to continue briefly into Dutch airspace, an action that alerts anti-aircraft defences.