| Page Created |

| June 22nd, 2022 |

| Last Updated |

| August 27th, 2025 |

| Great Britain |

|

| United States |

|

| Facilities |

| British Facilities U.S. Facilities |

| Related Pages |

| DUKW Landing Craft, Assault Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel U.S. Assault Teams Slapton Sands, Devon, Great Britain |

| U.S. Assault Training Centre |

| Documentary |

| Establishment and Purpose of the Assault Training Center |

When Britain declares war on Germany on Monday September 3rd, 1939, the immediate realisation comes that thousands of troops must be trained. That demand means not only soldiers, weapons, and instructors, but also land,vast amounts of it. Training grounds must be set aside quickly, even while Britain also struggles to grow enough food to feed its people. Every usable field is needed for crops and livestock. This creates a constant conflict between the Ministry of Agriculture, determined to increase production, and the War Office, determined to expand the army.

Whenever possible, remote or unproductive land with few inhabitants is chosen. It is promised that this land will be taken only for the war’s duration and returned afterwards. In practice, the countryside is transformed. Woods, moorland, and chalk downs become manoeuvre areas. Quarries and pits echo with rifle fire. On the coast, beaches are used to fire weapons safely out to sea.

For the first years of the war, these measures suffice. Infantry drill on heathland. Artillery fire across empty moors. Yet as 1943 begins, new demands appear. The invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe is no longer a distant ambition. At the Casablanca Conference in January, Roosevelt and Churchill formally commit to it. Stalin, though absent, presses hard for the Second Front to relieve pressure on the Red Army. Unlike British and Canadian troops, the arriving U.S. soldiers have no doctrine or training for storming defended beaches. This gap demands an urgent solution, as the invasion of France is only months away.

The invasion, later codenamed Operation Overlord, requires a type of training Britain does not yet possess. Soldiers must learn to storm defended beaches, supported by naval gunfire and aircraft. Entire divisions must land in sequence, moving from landing craft to shore in carefully timed waves. None of the existing British training areas are large enough for this.

Complicating matters, many beaches around the United Kingdom are already in use. The Royal Air Force occupies several for bombing and gunnery practice. The south and east coasts, once under threat of German invasion, are covered with mines, barbed wire, and anti-invasion defences. Very few stretches of coast remain open for large-scale exercises.

The Admiralty takes responsibility. It must oversee the formation of five Naval Assault Forces, each capable of carrying a division at assault strength. Commandos will also require places to train. To make this possible, troops need to rehearse landings under live fire. Naval destroyers, rocket craft, mortars, and aircraft must all be coordinated with the infantry advance. The flotillas and landing craft groups that make up the Assault Forces must also gain experience synchronising their movements with air strikes.

To find the land for this training, the Admiralty forms the Assault Training Area Selection Committee, chaired by Captain R. J. L. Phillips RN. Its task is to consult the War Office, the Air Ministry, and Combined Operations Headquarters, then identify and recommend suitable beaches. The terms of reference are clear: propose combined assault training areas for the needs defined by COSSAC, gather information from all relevant departments, and report on the sites. Reconnaissance parties must then survey the chosen areas to confirm their suitability.

In that same context, the U.S. Assault Training Center is therefore established in mid-1943 to create tactics and train American soldiers for amphibious assault against the Atlantic Wall. It becomes the only U.S. facility of its kind in Great Britain. Its success is judged vital. Later accounts declare that the outcome of the American landings on D-Day depends on its work.

Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Thompson is appointed to organise and command the new centre. Thompson, a West Point graduate and Army engineer, has studied German fortifications in the 1930’s. He is regarded as the Army’s leading authority on enemy defences. Arriving in England in April 1943, he activates the centre on paper and quickly assembles a staff of American and Allied specialists. Their task is to construct a new doctrine from nothing.

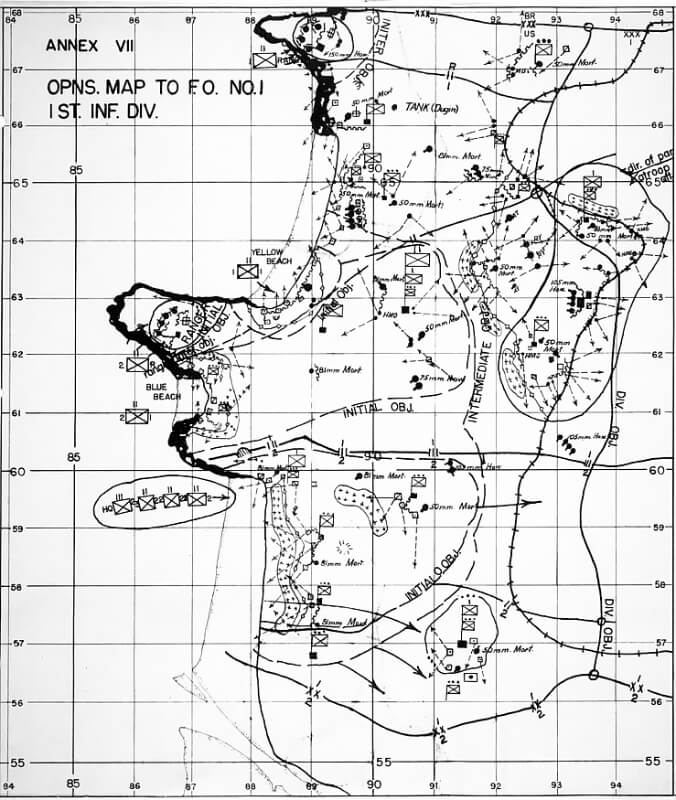

By May 1943, after a month-long conference, Thompson’s team completes its work. It draws on British, Canadian, and American experience, including lessons from the failed Dieppe raid. The new doctrine sets out the principles for attacking a defended coast. It notes the unique conditions of the American sectors. Omaha Beach is defined by steep bluffs and narrow exits. Utah Beach is bordered by flooded marshes and dunes. Unlike British and Canadian sectors, where tanks can drive directly inland, U.S. troops must fight their way clear before armour can land. Infantry and engineers must therefore learn to destroy obstacles and neutralise strongpoints with only the tools they carry ashore.

By June 1943, the overall situation is urgent. Only one close support range exists on the south coast: the Needles range, developed in late 1942 and used almost constantly since. But it is far too small, its beaches too exposed. New sites are essential.

Requirements are drafted. Two areas must lie within fifty kilometres of Milford Haven. Another must be found between Plymouth and Falmouth. A further site between Dartmouth and Prawle Point. Two more between Portland and the Needles. One between Yarmouth and Harwich. One between Bridlington and Spurn Point. Finally, two within the Rosyth Command in Scotland.

Each of the five Operation Overlord Assault Force’s is ideally to have two practice areas. Winter and spring training will be hampered by rough seas. By having two beaches facing in different directions, bad weather may close one but spare the other. A single area cannot suffice for an entire Assault Force. At best, it might allow battalion-scale rehearsals, or a brigade at most, but six battalions or more cannot train together in such space.

The distance from embarkation ports is also vital. Many landing craft are fragile, unseaworthy in heavy conditions. Long voyages for small vessels are dangerous and impractical. Training grounds must therefore be close to the ports from which the troops will embark.

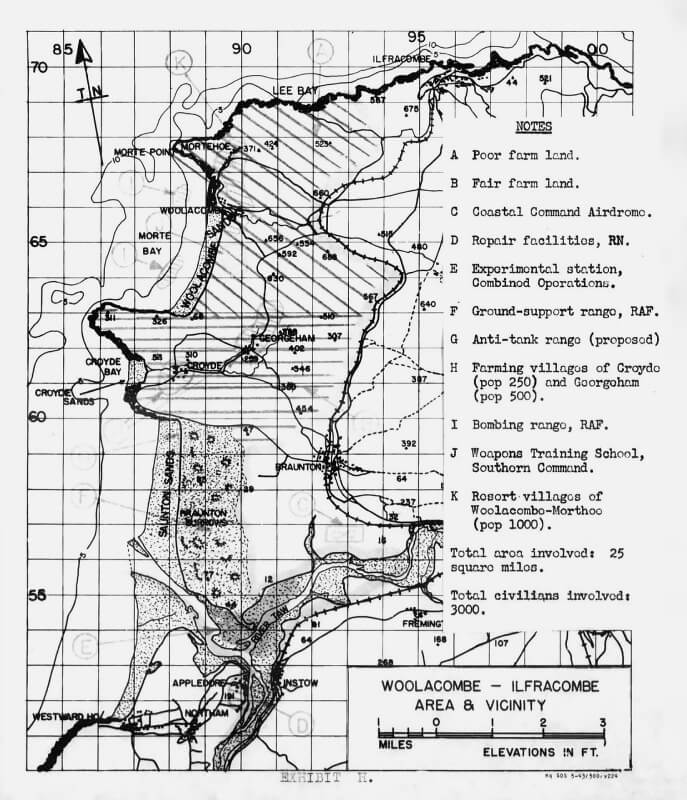

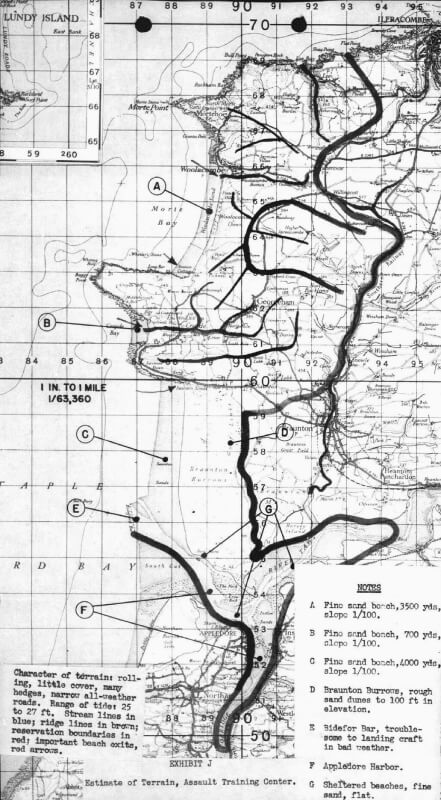

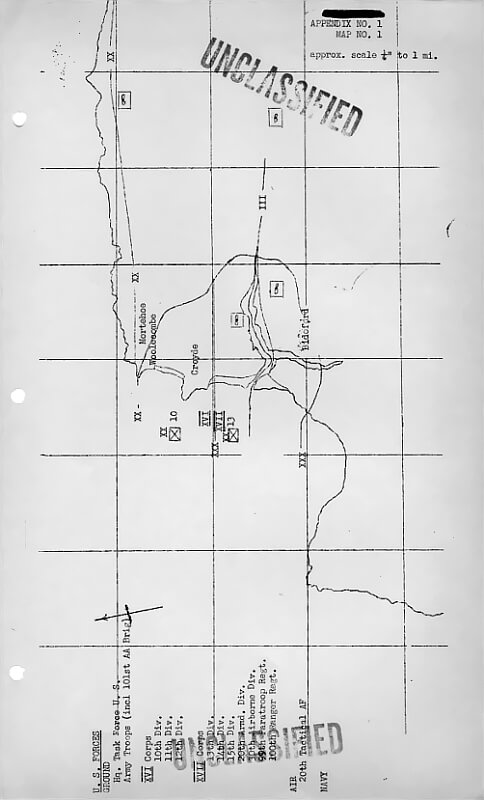

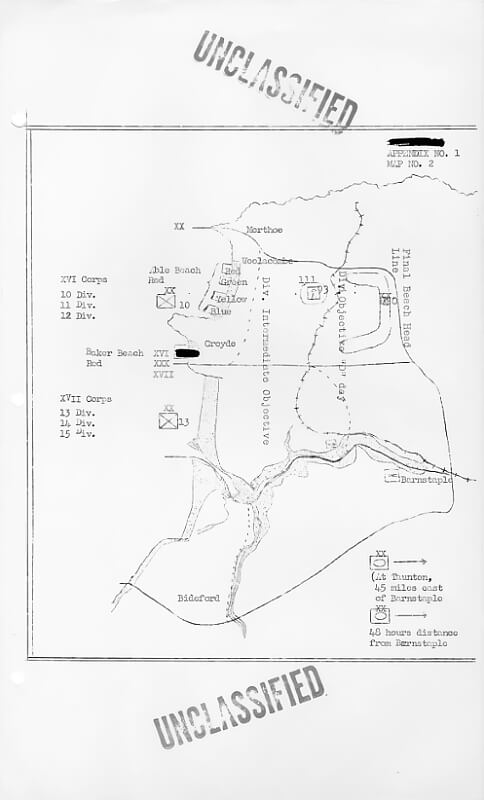

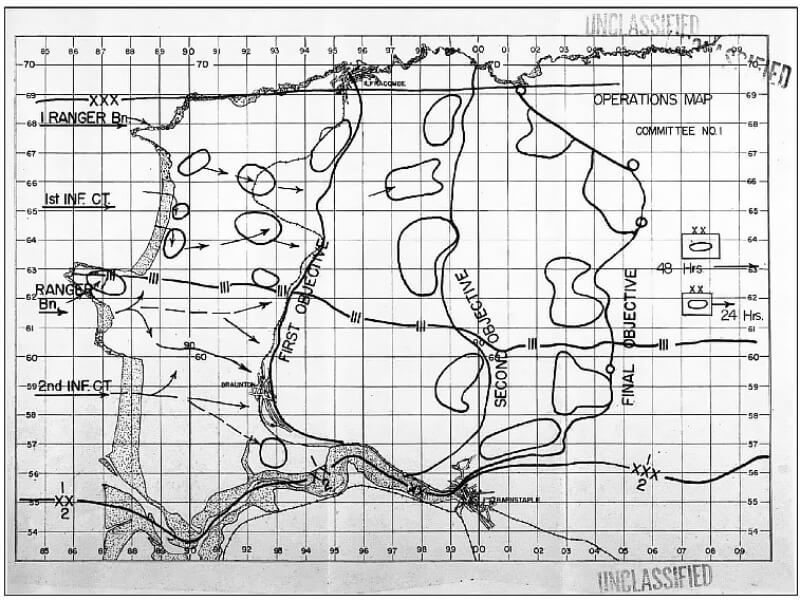

Finding a suitable training ground for the American troops is difficult. With most British beaches already taken for combined operations. The British keep the gentler shores for their own exercises. In spring 1943 British authorities offer the Americans the North Devon coast around Woolacombe and Braunton. Considered too rough for British training, the area proves ideal for the Americans. The beaches there mirror Normandy in tide, surf, sand, and terrain. Woolacombe’s profile is almost identical to Omaha Beach in slope and character. Saunton Sands and Braunton Burrows resemble the dunes and low-lying ground behind Utah Beach. These requirements expect to cover the needs of American forces. Woolacombe, is already earmarked for their use. No further beaches are anticipated for them.

The coastal stretch from Morte Point to the Taw-Torridge Estuary, around eleven kilometres in length, is assigned to the U.S. Army in mid-1943. Local authorities clear scattered minefields and evacuate a few farm buildings to make way for large-scale live-fire exercises. The Assault Training Center now has its ground: the exposed dunes of Braunton Burrows and the neighbouring beaches and headlands of North Devon.

Construction begins in August 1943. In August 1943 Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Thompson establishes his headquarters in the Woolacombe Bay Hotel. From here the Assault Training Center begins preparing the beaches for training.

Bulldozers arrive first. With chains they drag out old wooden posts left from 1940 invasion defences. Mines and barbed wire, laid when Britain expected a German landing, are cleared. New roads are built. A rough log track, soon known as the “Corduroy Road”, links Marine Drive to Putsborough. From the village, Bay View Road is joined to Rockfield Road. A steep track, the “Big Dip”, is cut to haul supplies from the beach. Paths are carved down from Marine Drive to the golf links. New pillboxes and wire entanglements are erected for assault practice.

Croyde Holiday Camp gets a new role. It is taken over to house troops undergoing intensive amphibious training for Operation Overlord. Officers are billeted in the chalets, while the surrounding fields are filled with barracks, tents, and training facilities. Elsewhere, the landscape changes on an even greater scale. “Tent cities” spring up across Braunton Burrows, covering the dunes with temporary encampments. At Braunton itself, a vast purpose-built camp is constructed. The engineers construct mock German defences. These include beach defences, bunkers and a dummy heavy anti-aircraft artillery site, complete with emplacements and revetments, and long lines of anti-tank obstacles set into the dunes. Mock-up landing craft on land are constructed to facilitate amphibious training.

On September 1st, 1943 the Assault Training Center is ready to receive its first trainees. Only nine months remain before D-Day.

| Multimedia |

| Life at the Assault Training Center |

The Americans quickly make Woolacombe their own. The Bungalow Café becomes the headquarters of the American Red Cross. Local women volunteer there, offering comfort and food.

Above the beach, Nissan huts are extended to house men. A vast recreation hall is built with polished wooden floors, a stage, and steel doors. Dances are held here, with local villagers invited. Archive accounts recall hot beef sandwiches, chocolate bars, and chewing gum. Transport is never a problem. If buses are full, the Army provides jeeps. Glen Miller is even said to have performed here.

Elsewhere, more buildings are requisitioned. Burrow Woods Camp near Lee houses over two thousand men. Hotels and cafés are taken over: the Pandora becomes a hospital, Belle View a military prison, the Boathouse Café the PX store. The Marisco Club is turned into the Forty Eight Club for Non Commsioned Officers. American Military Policemen patrol the streets. They enforce discipline harshly, locking offenders in the “glass house” or forcing them to march with heavy packs. Local children, however, adore them. Candy bars and chewing gum rain down from the guards at the prison gates.

For villagers, the presence of thousands of GIs changes daily life. The American band, billeted nearby, marches to the Woolacombe Bay Hotel to play the national anthem at flag-raising. Children listen to their music, or accept sweets and doughnuts from the soldiers. Chocolate and silk stockings become prized gifts. Friendships form quickly, and romances blossom. Several Woolacombe women later marry their American sweethearts and emigrate. Local boys scavenge from the training grounds. They collect brass detonators, discarded rations, even condoms, some used by demolition squads to waterproof fuses. Others sneak across the dunes to steal booby-trap parts, only to set them off by accident and flee in panic before the ambulance arrives.

| Multimedia |

| Layout and Construction of Training Facilities |

By summer 1943, once the site is secured, American engineers move into North Devon to transform the dunes into a live-fire assault training ground. Companies C, E, and F of the 398th Engineer General Service Regiment arrive in August to begin large-scale construction. Their task is to build facilities that replicate the German coastal defences which American troops will soon face in France.

The engineers divide the area into ten sections labelled A through M, omitting I, J, and K. Each section covers dunes, beach, or headland and is dedicated to specific aspects of training.

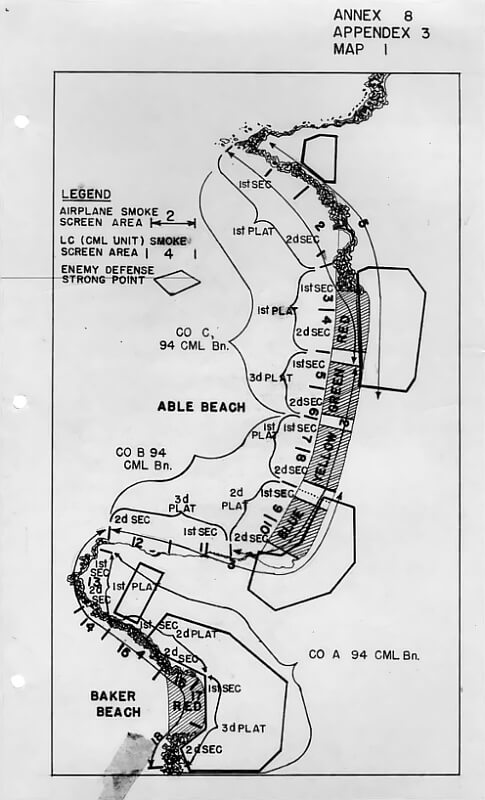

Area A runs along Crow Point, Broadsands and the Taw–Torridge Estuary. It is one of the busiest training zones of the Assault Training Center. It covers the southern end of Braunton Burrows at the mouth of the Taw–Torridge Estuary. The sector is divided into coded training beaches: Estuary Blue I and II, Estuary Red II, Estuary Green II, and Estuary Yellow II.

The sheltered waters make it ideal for rehearsing embarkation, loading, and debarkation. Amphibious vessels cross from the U.S. Navy base at Instow, where landing craft are stationed. On Broad Sands beach, soldiers practise embarking and landing from these craft under realistic conditions. Inland areas are used for specialist training and live trials with weapons.

Estuary Blue I runs along the seaward side of Crow Neck to Crow Point. This stretch of shoreline is later eroded heavily by the sea, but during 1943–44 it serves as a key training beach.

Estuary Blue II extends along the north shore of Broadsands from the White House almost to the beach access road near today’s car park. This is one of the main embarkation training sites. Structures for embarkation and landing are built along the strand. At the top of the beach, a lateral concrete wall survives, scarred with blast damage. Scattered obstacles remain in the sand, also showing explosion marks from live demolitions. At the White House, the Americans construct a concrete slipway, which still exists.

Estuary Red II lies on the south-eastern face of Crow Point. It is used as an alternative embarkation point, supplementing Green II.

Estuary Green II covers the eastern side of Crow Point. This area is designed for vehicle embarkation. Troops practise driving vehicles into landing craft under controlled conditions.

Estuary Yellow II continues anti-clockwise from the boundary of Blue II around the inner shore of Crow Neck to Crow Point. This section is covered up to low tide with replica German beach obstacles. Wooden stakes, ramps, and steel structures are positioned in the sand, mirroring those expected on the beaches of Normandy. Just inland, engineers build a mock-up area replicating amphibious landing craft. Many of these structures still survive, though in varying states of decay, and remain accessible today.

In this inland area, scale outlines of Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVPs) and Landing Craft Mechanised (LCMs) are marked out using scaffold poles. Soldiers rehearse movements on these mock-ups before proceeding to assembly areas for embarkation on actual landing craft at Broad Sands.

To the north of this site, six Landing Craft Tank (LCT) and two Landing Craft Mechanised replicas are built. These are large, substantial training structures with solid concrete bases. They are designed to represent Landing Craft Tank with ramps lowered, as if already beached. Around their edges stand six-foot scaffold poles, covered with canvas sheeting or corrugated iron to recreate the hulls of the craft.

The original concrete bases are constructed to the dimensions of the Landing Craft Tank Mark IV. When invasion planning shifts to the larger Landing Craft Tank Mark V, the replicas are extended. Additional aprons of concrete are laid to lengthen the decks and match the new dimensions. On one of these extended bases, the engineers leave their mark in wet concrete: the inscription reads “146th Eng, Co C, 1st Platoon.”

This combination of seaward beaches, embarkation points, mock landing craft, and vehicle practice sites makes Area A one of the epicentres of training at Braunton. Here thousands of soldiers experience their first realistic practice of the embarkation and assault sequence they will later perform in Normandy.

| Multimedia |

Area B lies in the southwest dunes near Braunton village. This area is designed for engineer training in obstacle clearance and demolitions. Engineers build the first training structures here, including replica German beach obstacles such as wooden ramps, barbed wire entanglements, and Czech hedgehogs. A demolition range is laid out for wire-cutting, Bangalore torpedo drills, and mine clearance. Portions of the estuary shore with beaches code-named Yellow I and Green I are also used occasionally for landing exercises. At Airy Point, a medical training site is established for casualty handling and field aid practice.

| Multimedia |

Area C covers the central dunes of Braunton Burrows. It contains several live-fire ranges and mock pillboxes for infantry weapons training. A large “rocket wall” of concrete is built as a backstop for bazooka practice. Soldiers fire M1 rocket launchers at painted bullseyes on the wall to improve accuracy and confidence. Scattered through the dunes are heavy concrete “faces” with painted embrasures, representing pillboxes. These are used repeatedly for gunnery drills and demolitions. Wooden mock pillboxes prove too fragile, as trainees continually demolish them, so engineers adopt permanent concrete targets that withstand repeated blasts.

| Multimedia |

Area D contains the greatest concentration and variety of assault ranges at the Assault Training Center. It is bounded inland by small lanes, to the north by the Braunton–Croyde road, and to the west by the beaches code-named Saunton Green, Yellow, and Red.

The area houses flamethrower and wire-cutting ranges, together with several large-scale training courses. Saunton Golf Course is requisitioned in its entirety. The clubhouse accommodates elements of the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion. Other parts of the course are given over to workshops, a motor pool, a tank park, and a flamethrower range. Training structures are also built on the fairways, though most are later demolished or buried beneath drifting sand.

One of the most prominent features is the obstacle course. It stretches more than 800 metres and is laid out across the dunes in the shape of a horseshoe. Teams of soldiers, five abreast, run the course. Obstacles include jumps, rope swings, balance beams, and climbing walls. The course is designed to test stamina, teamwork, and determination.

Another major installation is “Ship Sides.” This consists of three massive scaffold towers draped with cargo nets. Troops practise climbing down these nets to simulate embarking into landing craft from the sides of troopships.

Adjacent to the golf course lies the “Hedgehog.” This is the site of the Assault Tank Center’s final test, a demanding course of twelve obstacles designed to conclude each training cycle. Success here marks the culmination of the training programme for assault troops.

The realism of the training sometimes carries risk. In October 1943, during a live-fire crawl exercise at Braunton Burrows, infantry advance under overhead machine-gun fire. One weapon is incorrectly aligned. Its fire strays low into the training lane. Five soldiers are killed instantly. Fourteen more are wounded. The incident leads to tighter controls on the siting and supervision of live machine-gun ranges. Later that month, a mortar crew is conducting live-fire practice. A round explodes prematurely in the tube. Two soldiers are killed outright. The blast wounds several others. Training continues with mortars, but new precautions are enforced, including strict inspection of ammunition and barrels. During another exercise a 57-millimetre anti-tank shell falls through the roof of the Saunton Sands Hotel. At that time the hotel is housing the Duke of York School, evacuated from Dover. The incident underlines the hazards of live-fire training so close to civilian buildings.

Area D therefore represents the most diverse and challenging training ground within the Assault Training Center. It combines assault courses, specialist ranges, and large-scale obstacles to prepare soldiers for the physical and mental strain of D-Day.

| Multimedia |

Area E lies at Croyde Bay, north of Braunton Burrows. Its sandy, sheltered beach is used for small landing exercises and training with amphibious DUKW vehicles. The whole beach is code-named “Croyde Yellow II.” Troops practise ferrying artillery and supplies ashore as well as landing infantry. A large tented camp is established behind the dunes, near the present-day holiday park, with officers quartered in seaside cottages. Croyde serves as a bivouac and staging area for units rotating through training.

| Multimedia |

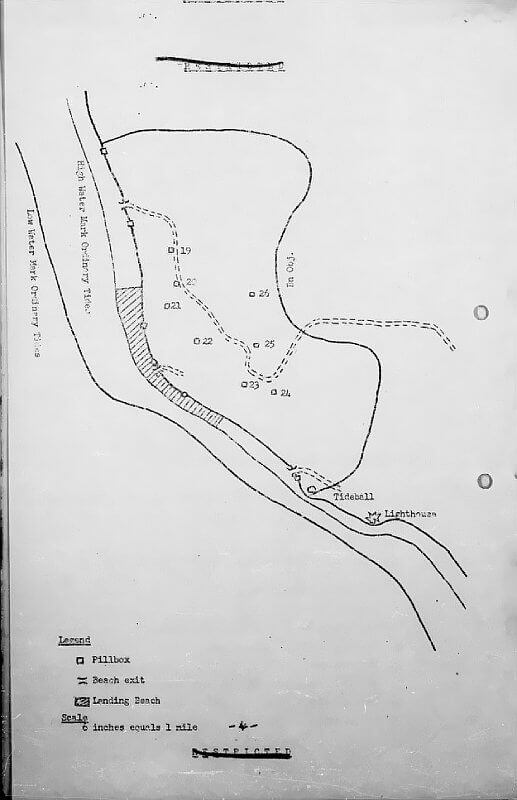

Area F is Baggy Point, a rocky headland between Croyde and Woolacombe. It is added in early 1944 for training in cliff assaults. Engineers build concrete pillboxes and “faces” against the cliffs and bulldoze gaps in hedgerows to create lanes of attack. Troops practise landing by DUKW on small coves, then climb cliffs to clear bunkers. In April 1944 the provisional Ranger unit of the 29th Infantry Division trains here for the planned assault on Pointe du Hoc. The unit later joins the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions in that mission on D-Day.

| Multimedia |

Area G is at Putsborough Beach, on the southern end of Woolacombe Bay. It is used for demolitions and small-scale cliff assaults. Engineers gather scrap timber and metal to build replica obstacles in the surf. Troops rehearse blowing them up with explosives. The cliffs also contain an old British pillbox that American soldiers repeatedly attack in live practice. Its remains are still visible on the cliff today.

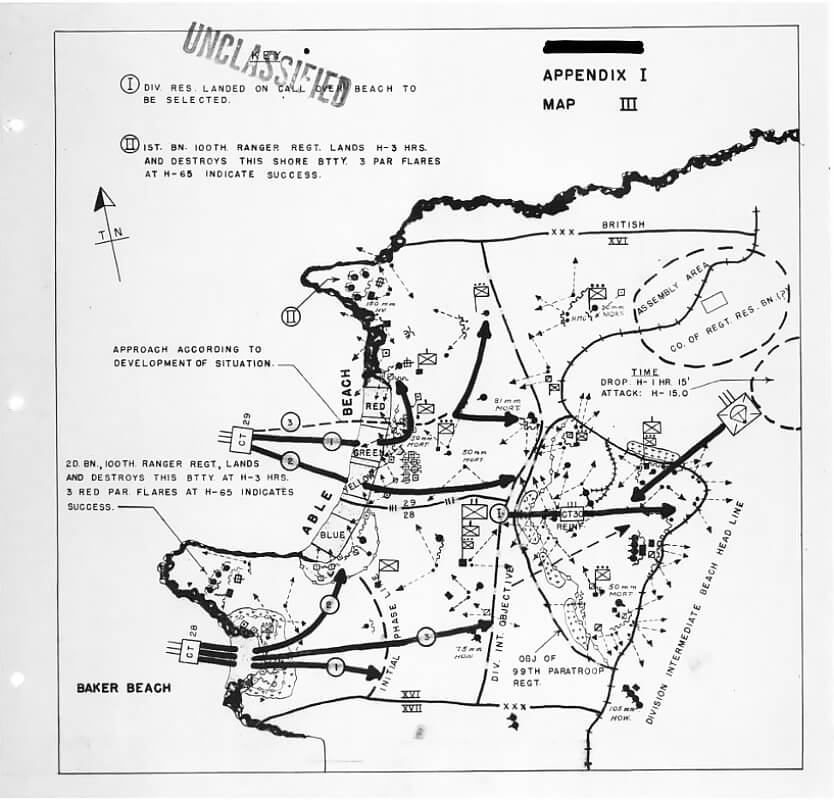

Area H is Woolacombe Sands, the main amphibious assault practice beach. Woolacombe Sands is the largest and most important assault training beach of the Assault Training Center. Its conditions closely resemble Omaha Beach in Normandy. For this reason, it hosts some of the most intense and large-scale exercises of the entire programme.

This beach is reserved for the trainee troops’ final seaborne exercise at the end of their three-week course. Each regiment or combat team completes its training here with a full-scale landing.

The sector is divided into four colour-coded beaches. Woolacombe Blue lies at Putsborough. Woolacombe Red lies directly in front of the village. Between these, below Marine Drive, are Woolacombe Green and Woolacombe Yellow.

Green and Yellow beaches are the primary landing zones for full regimental-scale exercises. Troops land here in successive waves of landing craft, supported by engineers and live fire. The beaches are divided into a chequerboard of small training squares. Each contains obstacles modelled on those expected in Normandy. Engineers and infantry train together to clear wire, destroy barriers, remove mines, and attack pillboxes. Demolition practice and live mine-clearing are routine here.

Woolacombe Red proves too dangerous for actual landings. The rocky shoreline makes it unsafe for amphibious craft. Despite this, some exercises still take place offshore. Accidents follow. On December 18th, 1943, three tank-carrying landing craft are swept off course in heavy surf. All three capsize. Nine soldiers of the 743rd Tank Battalion and five U.S. Navy crewmen are drowned.

| Multimedia |

Area L is centred on Woolacombe village. The Woolacombe Bay Hotel becomes headquarters for the Assault Training Center, housing offices, briefing rooms, and staff quarters. Local boarding houses are requisitioned for officers, and a seafront restaurant, the “Bungalow Café,” becomes an American Red Cross club known as the “Red Barn.” Woolacombe itself is filled with convoys, training troops, and the sound of landing craft offshore. Despite the intensity, the village also provides rest and recreation for rotating units.

| Multimedia |

Area M is at Morte Point, a craggy headland at the northern end of Woolacombe Bay. It serves as a target area for naval gunfire and heavy weapons. Royal Navy ships bombard the headland during live-fire demonstrations. American anti-tank guns are mounted on landing craft and fire at the cliffs. Allied aircraft stage strafing and bombing runs over the headland, demonstrating the scale of combined arms support soldiers will face on D-Day.

| Multimedia |

Throughout Braunton Burrows and its adjoining beaches, engineers construct their training facilities with speed and improvisation. Using timber, sandbags, scrap metal, and concrete, they recreate elements of the Atlantic Wall. Beach obstacles are set in rows. Dummy mines and booby traps are emplaced for engineers to clear. Replicated pillboxes and bunkers, often with reinforced concrete walls, are built to withstand repeated assaults. New gravel roads and marked junctions are laid across the dunes. Locals call one of the main tracks the “American Road.”

Supporting infrastructure develops at the same pace. At Braunton village a tent camp and Nissen hut camp, known as Braunton Camp, billet up to 4,250 men. Mess halls, kitchens, water points, shower blocks, and medical stations are constructed. The Saunton Sands Hotel and other requisitioned buildings provide classrooms and accommodation.

| Multimedia |

| Training Programme and Exercises |

As said, the Assault Training Center becomes operational in September 1943. From that moment the site runs on an intense cycle designed to prepare as many men as possible in the short time remaining before the invasion. Between September 1943 and May 1944, more than 14,000 American soldiers complete the course.

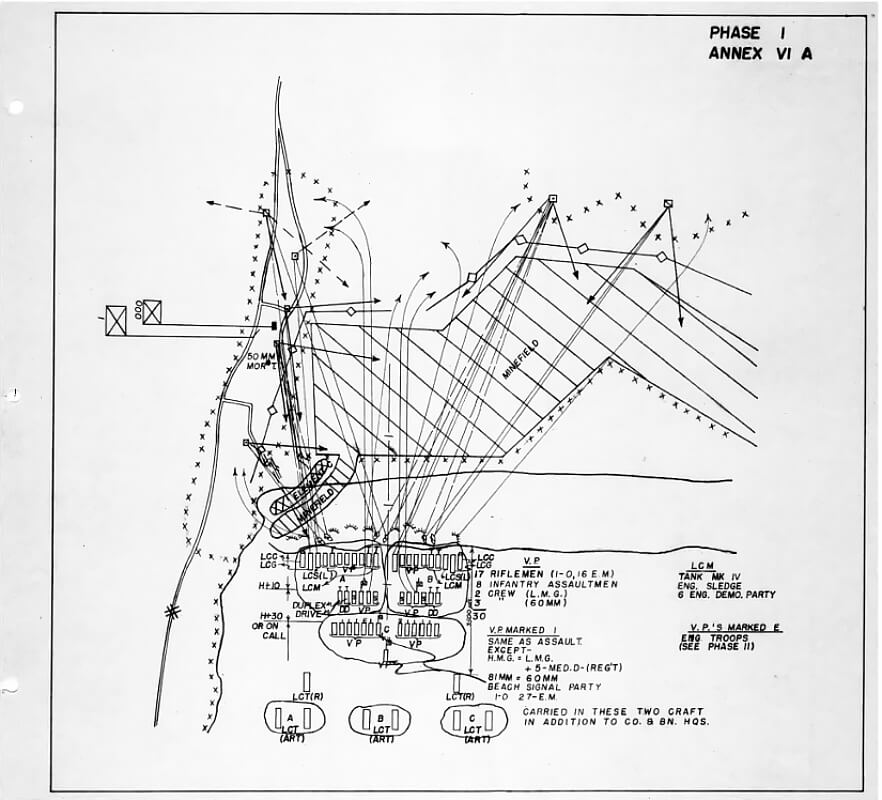

The first week focuses on individuals and small units. Soldiers learn new assault techniques at squad and platoon level. They are trained to fight in thirty-man “Assault Sections,” a special unit structure devised at Braunton. Each section, equal to the load of one Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP) landing craft, is led by a lieutenant with a staff sergeant. It contains riflemen, a bazooka team, a flamethrower operator, light machine-gunners, mortar crews, engineers, and demolitions men. Each section is capable of attacking and destroying a bunker on its own.

Across Braunton Burrows these sections practise movement, fire coordination, and use of specialist weapons. They train to fight for the “first thousand yards” of beachhead, as Colonel Thompson puts it. Live ammunition is used whenever possible. Infantry crawl under real machine-gun fire. Engineers blow wire and mines with live explosives. Mortar crews fire live rounds. The noise and danger are deliberate, intended to harden men against fear. Casualties are rare but not absent. In October 1943 a stray burst from a machine gun kills five men and wounds fourteen. In another incident two soldiers die when a mortar shell explodes prematurely. These accidents underline the deadly realism of the training.

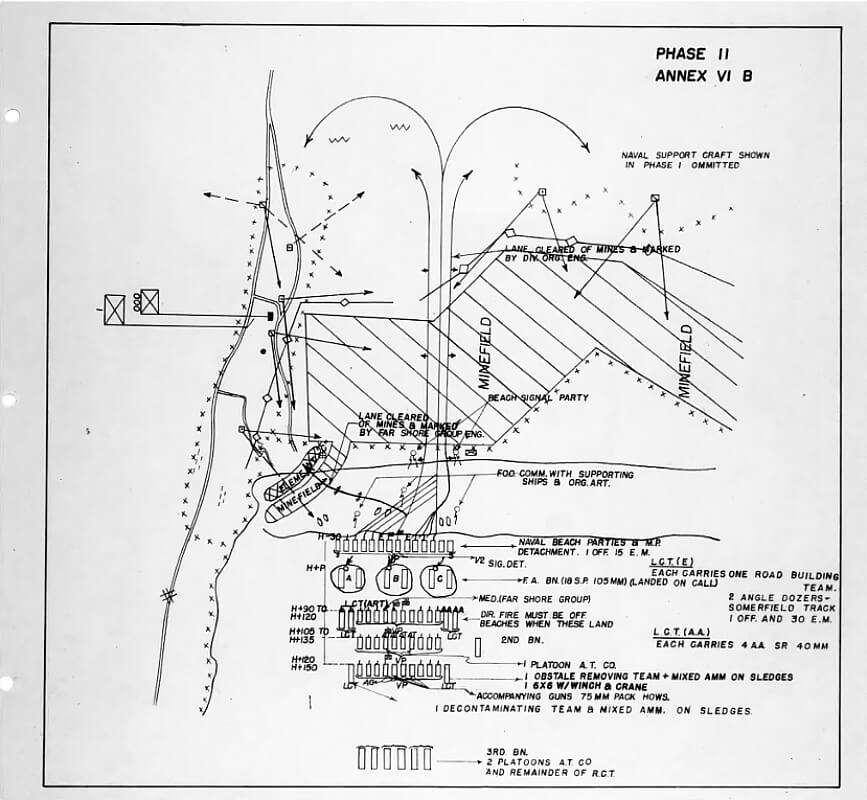

The second week is devoted to company and battalion tactics. After mastering small-unit skills, men advance to larger assaults. They rehearse company and battalion attacks, coordinating multiple Assault Sections with engineers clearing paths through wire and mines. At Baggy Point and other ranges, troops practise combined assaults. Rifle and BAR fire provide covering fire. Bazookas engage dummy emplacements. Engineers blow gaps with Bangalore torpedoes. Flamethrower teams practise against pillbox targets.

Specialist demonstrations are also held. U.S. Navy and Coast Guard officers teach boat loading and discipline for amphibious landings. Tank crews demonstrate how armour will exploit cleared beach exits. Naval and air power are displayed in full. Royal Navy ships offshore shell Morte Point. RAF Typhoons and Allied fighter-bombers rocket targets in the dunes. These displays reassure infantry that overwhelming firepower will support them on D-Day.

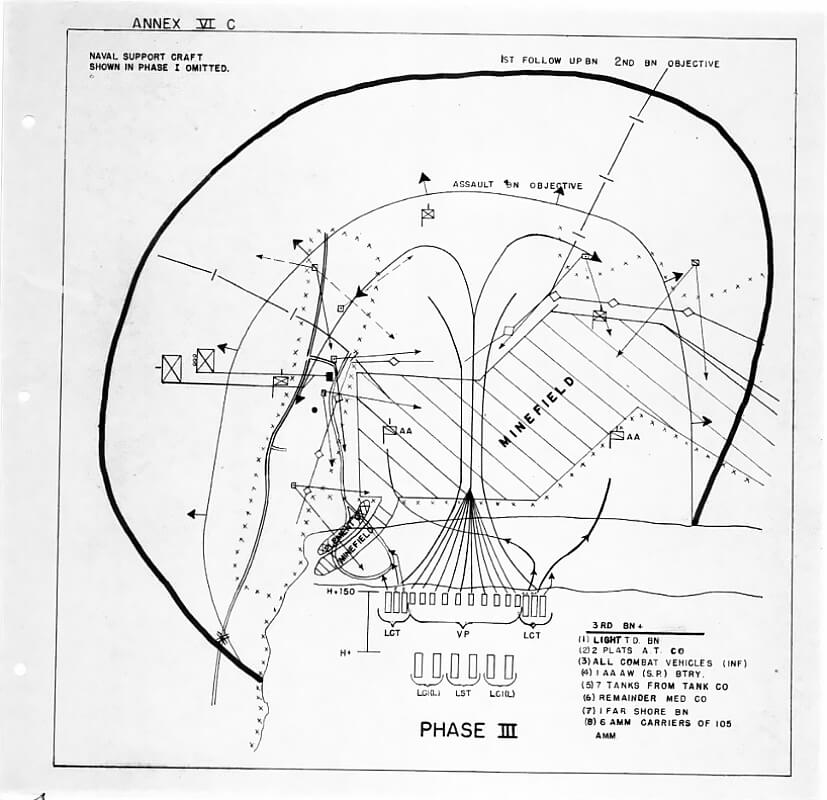

The third week ends with a full regimental landing exercise at Woolacombe Sands. The troops embark on landing craft, rendezvous at sea, and assault the beaches in timed waves. Navy crews practise approaches against the tide. Officers land in strict order. Smoke, live demolitions, and live fire add to the chaos. Soldiers pour ashore on Woolacombe Green and Yellow. Engineers blast gaps in obstacles. Infantry advance through barbed wire and mines under live overhead fire. General Eisenhower himself observes one of these division landings, the 28th Infantry Division, lifting morale.

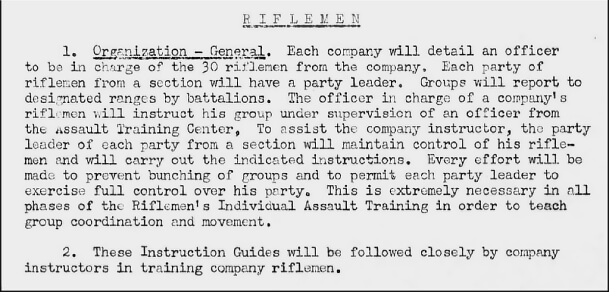

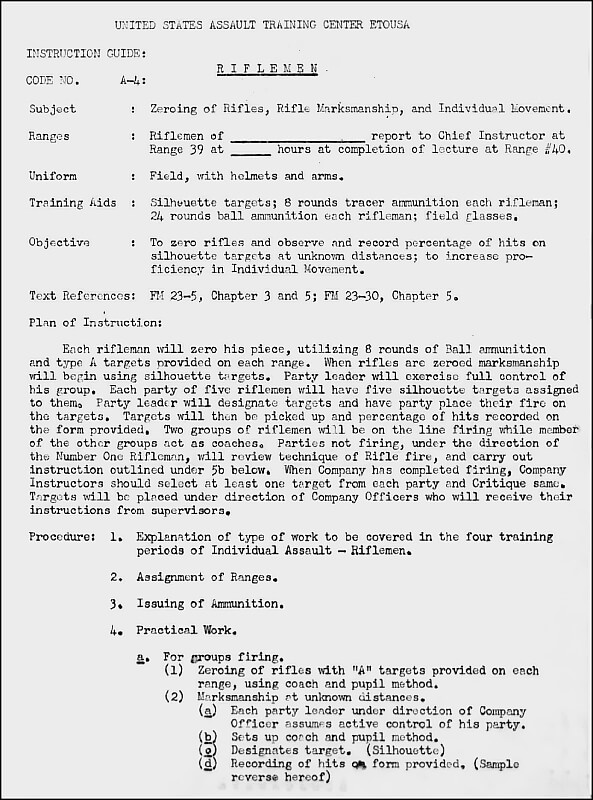

The training procedures for assault and support sections goes as followed. Weapons of the assault sections fall into two groups. Supporting weapons include rifles, Browning Automatic Rifles, machine guns, and mortars. These are already familiar to infantry units. Company officers are responsible for training in their use. They are provided with instruction guides, advisers from the Assault Training Centre staff, and suitable training aids. Officers must prepare daily instruction based on the guides. They are expected to carry the guides at all times for reference. Infantrymen armed with these weapons must become fully proficient in their operation and care.

Co-ordinated weapons are more technical and less familiar. These include rocket launchers, flame-throwers, demolition charges, and wire cutters. Training in these weapons is conducted by Assault Training Centre instructors. All officers, non-commissioned officers, and members of the training cadre assist in this instruction.

When organising individual assault training, each company assigns qualified officers to accompany consolidated parties to the ranges. These parties attend rifle, mortar, automatic rifle, machine gun, and demolition ranges. Other officers may attend rocket, flame-thrower, or wire-cutting ranges if available. It is considered essential that the company weapons platoon leader commands the mortar party. Previous experience with mortars is required to provide reliable instruction in this weapon.

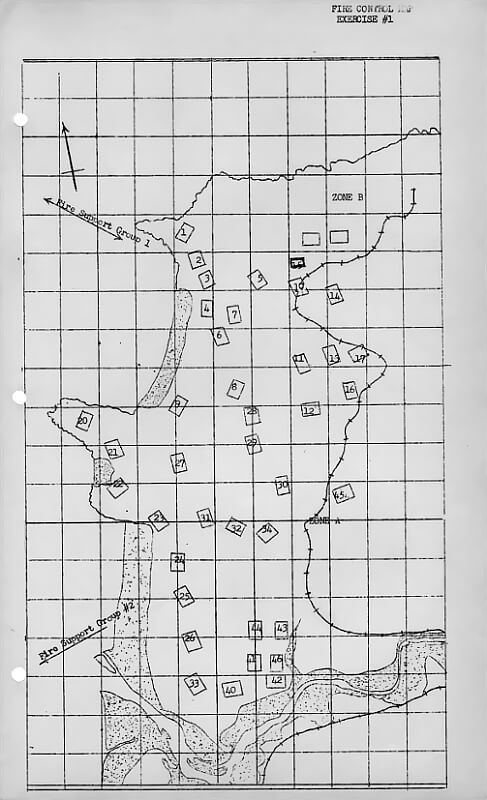

Team assault training begins with dry runs. These are regarded as the most important stage of training. The section leader trains his section in co-ordination of fire and movement. Normally one staff instructor from the Assault Training Centre supervises every third dry run. A section can complete three dry runs within four hours. Each company rotates its six sections through different runs. This rotation ensures that every section benefits from staff suggestions, experiences different terrain, and is scored on performance.

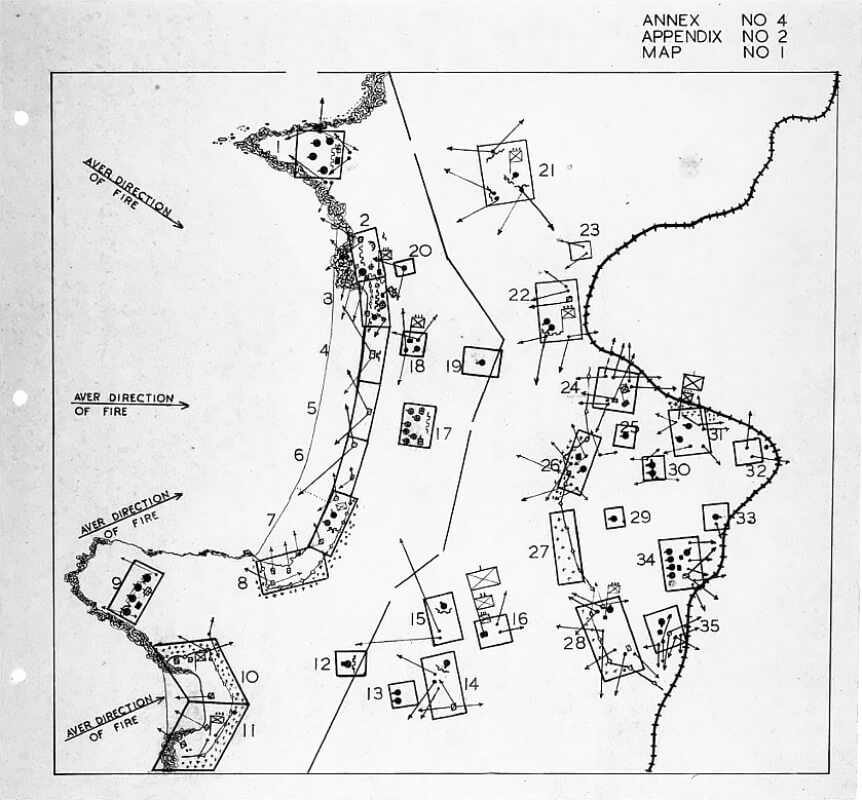

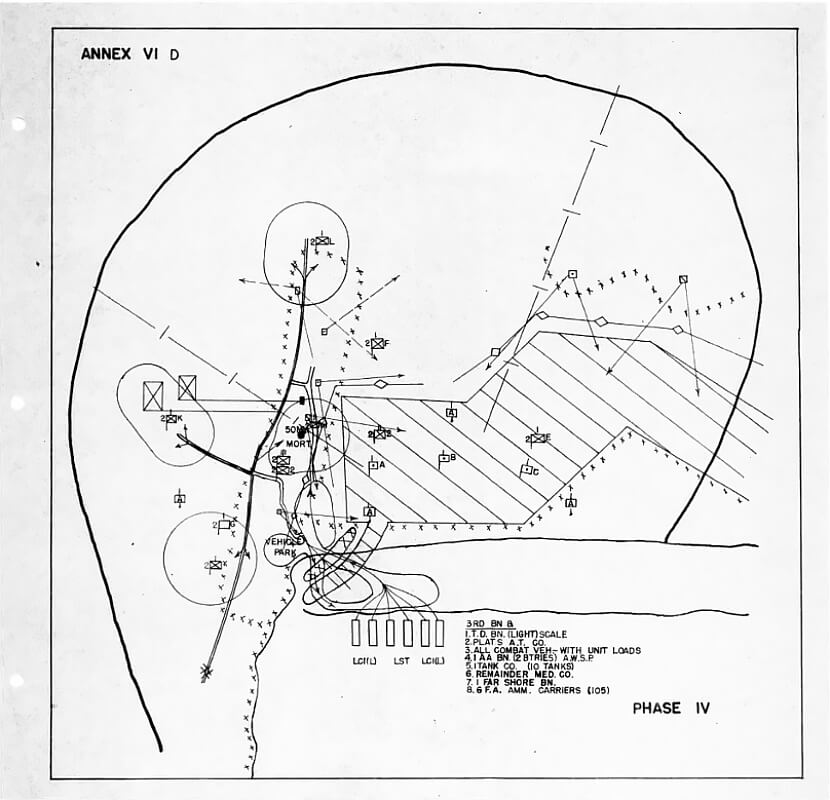

After dry runs, live firing begins with ball runs. Assignments to ranges are made to ensure suitable ground for support fire. A company will have two sections firing live ammunition while two sections receive instruction in mines and booby traps. Assault companies use ranges 38 and 39, ranges 41 and 42, and ranges 45 and 46. Support companies use ranges 47, 48, and 49. The cadre uses range 50 for dry runs and range 51 for ball runs. Ranges 47 to 49 allow the 81-millimetre mortar to fire at visible targets. Bursts can be observed while still meeting safety requirements.

Ranges for both dry and ball runs are assigned by battalion and company. Sections are therefore fully aware of their assigned ranges and duties before the exercise begins.

For individual assault training, the Regimental Munitions Officer delivers ammunition to supply points for serials A-4, A-5, A-6, and A-7. Training aids are delivered to the supply points by Area Maintenance Engineers.

For team assault ball runs, ammunition and other aids are delivered to battalion bivouac areas at least twenty-four hours before the exercise. A breakdown of supply is issued to battalion quartermasters, showing the exact allotment for each assault and support section. Ammunition is distributed in the battalion area, including loaded and charged flame-throwers. Sections must arrive at the ranges properly equipped and supplied, at the time stated in the schedule.

Crimpers and wire-cutters are distributed through the Regimental quartermaster before the first training serial. Each section draws two crimpers. The leader of the wire-cutting party carries one, and the leader of the demolition party carries the other. Each section also draws four wire-cutters, carried by members of the wire-cutting party. Dummy Bangalore torpedoes are drawn by battalions from the Training Aid depot.

Training time is often lost through preventable mistakes. Training aids and ammunition are sometimes not delivered to the correct place or at the correct time. Ranges are not always assigned down to section level before exercises. Demolition charges are sometimes unprepared when required. Flame-thrower cylinders are not always collected from the flame-thrower range, or fuel tanks are not filled. Weapons sent by vehicle occasionally fail to arrive or are sent to the wrong location. Some weapons arrive in an unserviceable condition. Too few magazines are sometimes issued for Browning Automatic Rifles. Rifle grenade launchers are on occasion not provided.

The system proves effective. Soldiers later recall that the terrifying sounds of battle are less shocking on D-Day because they have heard it all before in North Devon. Many veterans state that the hardest day of their war was not June 6th but a day on Braunton Burrows when an exercise went wrong yet they endured.

To run this pipeline efficiently, the Assault Training Center uses a “train-the-trainer” system. When a new division arrives, a cadre of its officers and Non-Commsioned Officers first attend a shortened course. They then help to instruct the rest of their unit under Assault Training Center supervision. The 29th Infantry Division, for example, sends an initial group for ten days. These men return to train their own regiments with Assault Training Center staff assisting. This system allows multiple divisions to rotate through in time for the invasion.

By spring 1944, all three American infantry divisions selected for Normandy, the 1st, 29th, and 4th Divisions, pass through Braunton. Numerous attached units also complete the course, including combat engineers, naval beach battalions, chemical and medical units. Even elements of the 101st Airborne Division attend a short five-day course in April 1944. Their commanders consider it useful that some paratroopers understand the latest assault techniques, even though they will arrive by air.

The training grounds evolve as new information arrives from Europe. When larger Landing Craft Tank Mark V landing craft are assigned to D-Day, engineers lengthen the concrete mock-ups to match. When the British develop Hobart’s specialised armoured vehicles, American officers attend demonstrations at Westward Ho!, though U.S. commanders ultimately reject most of them. The Assault Training Center stresses conditioning as well as tactics. Troops run obstacle courses in full kit, scale cliff ladders, and carry casualties across the dunes. Colonel Thompson insists the men be exposed to the full “sights and sounds of battle” before Normandy.

Notable figures emerge from the centre. In March 1944 Colonel Thompson, awarded the Legion of Merit for his work, hands command to Colonel John B. Horton. Thompson takes a combat role for D-Day. Landing with the first wave at Omaha, he sees some of his former trainees pinned down. He organises an impromptu assault group and personally leads them against a strongpoint. The position falls but Thompson is severely wounded. His actions, shaped by the very training he created, likely save many lives.

Other Assault Training Center staff also serve in Normandy. Colonel Lucius D. Chase, chief of training, holds important responsibilities during the invasion. Units that build and maintain the Braunton ranges, such as the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion, are among the first ashore. Their men clear obstacles under fire, exactly as rehearsed. One of them, Private Alfred Augustine, had scratched his name into wet concrete at Baggy Point during construction. On June 6th, 1944 he is killed in the first wave at Omaha. His name remains on the training ground, a lasting trace of a soldier lost in battle.

Some graduates are decorated for gallantry. Captain Sam H. Ball of the 146th Engineer Battalion is awarded the British Distinguished Service Order by Field Marshal Montgomery for bravery under fire. His honour symbolises the link between the hard training on the Devon dunes and the success in Normandy.

By the time the invasion begins, the Assault Training Center has fulfilled its purpose. Its harsh lessons, learned in sand and surf under live fire, carry directly onto the beaches of France.

| Multimedia |

| A regimental Landing Exercise at Woolacombe Sands |

As said earlier, the third week and final phase of training at the Assault Training Center takes place at Woolacombe Sands. This exercise was known as “Exercise Hedgehog”.A full regimental combat team, with attached engineers and support units, rehearses the entire sequence of a D-Day assault.

At dawn, troops assemble in bivouac areas inland. Final checks are made on weapons, equipment, and demolition stores. Engineers prepare explosives, Bangalore torpedoes, and mine detectors. Assault sections are briefed on their landing areas.

The soldiers march to the embarkation hards. Here they board landing craft waiting in the Taw–Torridge Estuary or nearby coastal anchorages. Troops climb aboard under strict naval discipline. Vehicles and supplies are loaded onto Landing Craft Tank. Once complete, the craft form up in convoy and head out to sea.

Off Woolacombe Sands, Royal Navy vessels are already in position. Minesweepers have cleared approach channels. Bombarding ships and rocket-firing craft line up offshore. At H–Hour the naval bombardment begins. Heavy guns pound the beach defences. Aircraft roar overhead and strike target markers in the dunes. Rocket craft unleash salvos that slam into the shoreline.

Landing craft circle in the Channel before turning towards the beach. They form into assault waves, each group assigned to a coloured sector. Woolacombe Green and Yellow are the main landing zones.

As the ramps drop, assault troops dash into the surf. Engineers wade forward with mine detectors and Bangalore torpedoes. Barbed wire is cut or blown apart. Wooden stakes and hedgehogs are destroyed with demolition charges. Infantry squads provide covering fire as engineers clear the way. Bazooka and flamethrower teams attack dummy pillboxes. Mortar crews give smoke cover as units push off the sand.

The exercise beach is laid out in a chequerboard of “problem areas.” Each square contains a different obstacle or challenge. One may hold a mined wire entanglement. Another may contain a mock concrete bunker. A third may hold flooded ditches. Assault sections move square to square, clearing each in sequence.

Casualties are simulated with markers or live-fire stress. Soldiers drag “wounded” comrades to cover. Engineers detonate real charges, and the sound of live machine-guns overhead reinforces the chaos.

By mid-exercise the regiment has pushed through the dune line. Company commanders regroup their men. Engineers clear inland routes for vehicles. In some exercises, tanks land from Landing Craft Tank and drive off the beach, supported by covering infantry.

The advance continues inland until the regiment secures designated assembly areas behind the dunes. At this point observers call a halt. Senior officers, sometimes including generals, assess the performance. On several occasions General Eisenhower watches the landings, noting the realism of the drills.

The exercise ends with troops marching back to camps, tired, wet, and often shaken. For many, the experience is the most demanding day of their training. Yet the lessons prove invaluable. By June 1944, soldiers who land in Normandy recognise the obstacles, the noise, and the fear. They have already faced them on Woolacombe Sands.

| Multimedia |

| Post-D-Day Legacy and Current State of the Site |

By May 1944, as the Normandy invasion approaches, the mission of the Assault Training Center is complete. The last units finish their courses and depart to staging areas for embarkation. In the first week of June, every American soldier destined for Omaha or Utah has trained at Braunton Burrows in some form. The Devon dunes have prepared them for the greatest amphibious assault in history.

Once the invasion begins, the camp’s purpose changes. In July 1944 the U.S. Army redesignates Braunton as the 18th Field Force Replacement Depot. The ranges fall silent. Instead of training, the site now processes replacement troops arriving from the United States. These men wait here before being shipped across the Channel to reinforce units already fighting in France. Thousands pass through in this way. The depot continues to operate until the war in Europe ends in May 1945.

After the war, the training structures are gradually dismantled or left to decay in the sand. Some traces survive: the concrete “rocket wall” in the dunes, the outlines of landing craft mock-ups, and scattered remains of demolished obstacles. Over time the Braunton Burrows return to nature, though relics of 1943 and 1944 can still be found.

Today, Braunton Burrows is both a nature reserve and a place of memory. A memorial on Woolacombe’s esplanade honours the American troops who trained there. Visitors still walk the beaches and dunes where soldiers once rehearsed the assault on Hitler’s Atlantic Wall. The site remains a reminder that the hard lessons of North Devon shaped the outcome of D-Day.

| Sources |

| Documents, Conference on landing assaults, 24 May – 23 June 1943 |