| Page Created |

| May 16th, 2025 |

| Last Updated |

| May 17th, 2025 |

| Canada |

|

| Great Britain |

|

| The United States |

|

| Related Pages |

| Office of Strategic Services Special Operations Executive |

| Camp X, Ontario, Canada |

Camp X is built in isolation along a desolate stretch of the Lake Ontario shoreline, about an hour’s drive east of Toronto. Situated on 110 hectares of sparsely inhabited farmland between the towns of Oshawa and Whitby, the site includes a half-dozen buildings and a variety of training facilities.

Camp X is formally established on December 6th, 1941 by Sir William Stephenson, the head of British Security Coordination. A Canadian from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Stephenson is a trusted confidant of both Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His role in fostering Anglo-American cooperation in covert operations is central to the early development of wartime intelligence efforts.

The British government had establishes the British Security Coordination as a covert intelligence outpost in New York City in 1940. Operating from offices in the Rockefeller Center, British Security Coordination is officially disguised as “British Passport Control,” a nondescript title that conceals its true function.

In reality, British Security Coordination serves as the principal liaison between the British Special Operations Executive, the Great Britain’s clandestine warfare agency, and emerging American intelligence figures, including those involved in the formation of the Coordinator of Information and later the Office of Strategic Services. Its presence is instrumental in fostering early cooperation between the two nations in the fields of espionage, sabotage, counter-intelligence, and psychological warfare.

| Multimedia |

| Camp X |

In early 1942, Garland H. Williams and several others selected for the new clandestine operations and intelligence sections of William Donovan’s organisation begin practical training at a secret British camp just across the Canadian border. Like said, Camp X, is specifically established to instruct agents in the methods of sabotage, infiltration, and guerrilla warfare. Prior to the United States’ formal entry into the war, Donovan had been hesitant to organise American commando units. But with the attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war in December 1941, that reluctance disappears.

In fact, plans for a joint training facility begin even earlier. In September 1941, with Donovan’s encouragement, the British agree to construct a secret paramilitary training camp near Toronto to replicate the Special Operations Executive schools in Britain. The camp is intended to serve a dual purpose: to train American operatives in the techniques of irregular warfare, and to serve as a vehicle for strengthening Anglo-American cooperation in covert activities.

Under the direction of Sir William Stephenson, head of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), the groundwork for Camp X is quietly laid in rural Ontario. To conceal the operation’s true purpose, a Vancouver businessman named A.J. Taylor is tasked with securing the land. He purchases approximately 110 hectares, near Oshawa for $12,000, registering the transaction under the inconspicuous title of “Rural Realty Company, Ltd.”

The property is ideally suited for covert training. It features a varied landscape of open fields, dense woodland, swampy lowlands, and a rugged stretch of shoreline along Lake Ontario. At the time of purchase, it includes a farmhouse and several storage buildings. These are soon supplemented with purpose-built structures, including barracks, classrooms, and a dedicated facility for radio equipment and communications, part of what would later become the Hydra station.

Because of its pastoral surroundings, students and staff affectionately refer to the facility as “The Farm.” Officially, however, it is designated Special Training School No. 103 (STS 103), a cover identity used by the Special Operations Executive. However, it functions under several designations, depending on the administrative authority involved. To the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, it is known as S 25-1-1; to the Canadian military, it is referred to as Project-J.

Construction of Camp X is completed by that same first week of December 1941, and the camp opens on December 9th, 1941, just one day after the United States enters the war. To maintain secrecy, locals are told that the camp is a military storage depot. Camp X is operated jointly by British Security Coordination and the Government of Canada. The camp’s first commandant is Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Terence Roper-Caldbeck.

On April 5th, 1942, William E. Fairbairn—renowned for his brutal hand-to-hand combat techniques and widely considered one of the world’s most dangerous “silent killers”, arrives at Camp X to begin instructing operatives in close-quarters battle. Yet his first night at Camp X very nearly ends in disaster.

Shortly after nightfall, a fire breaks out in the mess hall. Constructed almost entirely of wood, the structure burns rapidly, and flames begin spreading toward the sleeping quarters. As the alarm is raised, camp guard Mac MacDonald rushes to evacuate the buildings. He finds Fairbairn in his room, calmly attempting to gather his personal belongings. Despite MacDonald’s urgent pleas, Fairbairn refuses to abandon his possessions.

With the fire threatening to engulf the building, MacDonald calls for backup. The man who answers is George de Relwyskow, a fellow instructor and former Olympic medal-winning wrestler. Without hesitation, de Relwyskow smashes through the window and assists MacDonald in forcibly dragging Fairbairn to safety, leaving behind all of Fairbairn’s valuables, but sparing his life.

Though the fire causes significant damage to the camp’s facilities, there is only one casualty: Bessie, the beloved dog of the camp’s first commandant, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Terence Roper-Caldbeck.

Later, in 1942, command passes to Lieutenant Colonel Richard Melville Brooker of the British Army, who takes a more active role in the camp’s daily operations and instructional leadership. Though admired by many for his energetic and charismatic approach to training, Brooker remains a somewhat controversial figure within Office of Strategic Services circles due to his lack of direct operational experience behind enemy lines.

In March 1943, Camp X undergoes a significant change in leadership. The Office of Strategic Services, impressed by the popularity and effectiveness of Major R.B. “Bill” Brooker, requests his transfer for duties elsewhere. As a result, Brooker steps down from his position as commandant of Camp X, where his charismatic leadership and engaging instructional style had made him a favourite among American trainees.

To succeed him, British authorities appoint Lieutenant Colonel Cuthbert Skilbeck, who becomes the camp’s third and final commanding officer. Skilbeck, known for his competence and professionalism, assumes control at a time when Camp X’s role in the Allied training programme is beginning to shift. As the war progresses and the focus moves increasingly toward the Pacific theatre, the camp continues its operations under Skilbeck’s steady hand, ensuring that agents departing for missions in Asia, Europe, and beyond are equipped with the skills and mindset necessary for clandestine warfare.

By the latter half of 1944, as Allied forces liberate occupied territories across Europe, the strategic need for newly trained clandestine agents begins to diminish. The Special Operations Executive, which had once urgently required operatives for sabotage and subversion missions behind enemy lines, now finds its demand for fresh personnel steadily declining. With the tide of war turning in favour of the Allies, the intense training efforts of earlier years begin to scale back.

As a result, Camp X, the once-secret facility on the shores of Lake Ontario that had trained dozens of agents from the British Special Operations Executive and the American Office of Strategic Services, quietly closes its doors.

Yet the expertise developed at Camp X is not entirely shelved. Some of its seasoned instructors are reassigned to Commando Bay in British Columbia, a more remote training site that becomes a hub for preparing agents for the continuing war in the Pacific. Among those trained there are Asian-Canadian recruits, who are particularly valuable for missions in Japanese-occupied territories due to their linguistic and cultural familiarity.

| Multimedia |

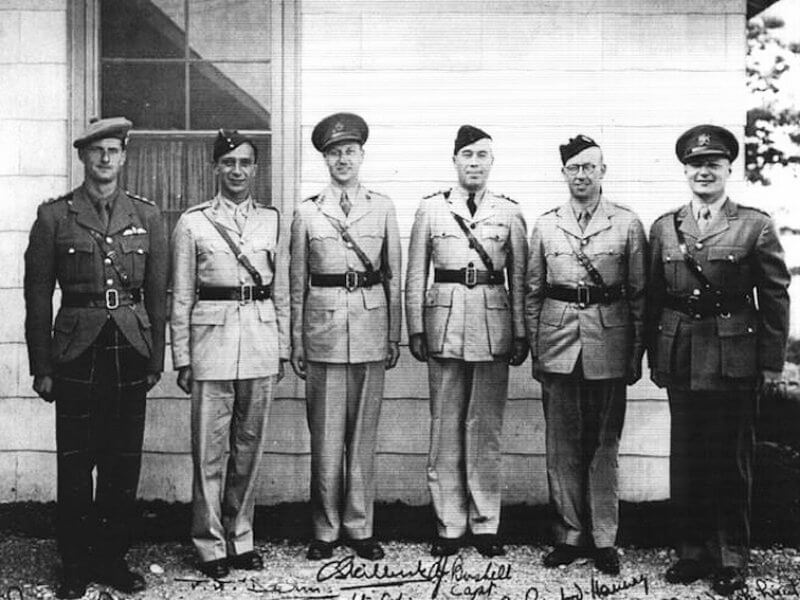

Captain Pelham Burn, Major Dehn, Lieutenant Colonel Cuthbert Skilbeck, Captain Bushell, Captain Rainsford-Hainey, and Lieutenant Walsh.

| American Cooperation |

The first contingent of American personnel arrives in February 1942. Among them is Garland H. Williams, one of the key architects of Office of Strategic Services training. The initial group, comprising about a dozen individuals, undertakes a four-week special operations course. By April, Camp X is training not only administrators and instructors from the Office of the Coordinator of Information but also the first generation of American field agents destined for assignments in India, Burma, China, North Africa, and occupied Europe. Additional recruits from both the Special Operations and Secret Intelligence branches follow over the coming months.

The impact of British training support extends beyond Camp X. British officers not only advise the Office of the Coordinator of Information and Office of Strategic Services on the structure of their training programmes, but also provide instructors, manuals, lesson plans, and course materials. They lend equipment, explosives, and weaponry developed by the Special Operations Executive and grant American personnel access to Special Operations Executive’s own advanced training schools in Britain. According to a postwar Office of Strategic Services report, the British contribution to Office of Strategic Services training during this early period is essential: “Too much credit cannot be given to the aid received from British Special Operations Executive at this stage of the game. British Special Operations Executive play a great part if not the greatest in the planning of the new Special Activities/Goodfellow, i.e. Special Operations schools.”

The ethos behind British commando training shapes the entire culture of Camp X and, by extension, the Office of Strategic Services. As one British manual describes it, the commando “started free of all the conventions which surround a traditional corps.” The aim is to merge the flexibility and independence of guerrilla fighters with the discipline and firepower of regular troops. The commando is trained to climb cliffs like a Pathan, live off the land like a Boer, and vanish like an Arab before an enemy can pin him down. With his grenades, Bren gun, and Thompson submachine gun, he is to be equally at ease in rugged terrain, hostile towns, or behind enemy lines.

By the end of its first year, Camp X has trained dozens of American agents and instructors, both from Special Operations and SI, laying the groundwork for a lasting partnership between the Office of Strategic Services and Special Operations Executive. The collaboration at Camp X marks the beginning of a transatlantic relationship in covert warfare, one that fuses British expertise with American energy and sets the tone for joint operations throughout the remainder of the war.

| Multimedia |

| Training |

Training at Camp X focuses on the fundamentals of irregular warfare. In groups no larger than a dozen, trainees learn the essentials of infiltration, fieldcraft, camouflage and concealment, silent killing, sabotage, and the use of Allied and enemy weapons. Hand-to-hand combat, leadership of guerrilla forces, and basic espionage techniques form the core curriculum.

The British bring to Camp X a deep reservoir of experience in guerrilla warfare, sabotage, and irregular operations, forged through decades of colonial conflict and counter-insurgency across the British Empire. From the rugged landscapes of Turkey to the politically charged streets of Ireland, British forces have developed and refined a system of covert training that now forms the foundation for the curriculum at Camp X. This expertise is condensed into an intensive training programme lasting three to four weeks—designed to turn civilian recruits and military personnel alike into highly capable covert operatives.

There is no fixed syllabus at Camp X. Instead, instructors tailor each course to the specific needs of the trainee groups, adjusting based on the theatres of war to which they are destined and the nature of their future assignments. An agent tasked with gathering intelligence on troop movements in North Africa requires a vastly different skillset from a saboteur sent to blow up railway bridges alongside the French Resistance. Flexibility in training is therefore essential.

Despite this variation, several core skills are taught to all who pass through Camp X. Every trainee learns to read and draw maps, move undetected, conceal themselves in both urban and rural settings, and maintain an inconspicuous appearance. Firearms training departs from the conventional military emphasis on precision shooting. Instead, operatives are taught “instinctive gunfighting”, the ability to react, draw, and fire immediately without adopting a formal stance or even using the weapon’s sights. In hostile territory, hesitation can mean death.

Close-quarters combat is another critical component. Trainees are drilled in techniques for silently incapacitating guards and sentries when firearms are either unavailable or too noisy to use. The instruction, influenced heavily by the brutal system developed by William E. Fairbairn and Eric A. Sykes, emphasises lethality, speed, and psychological domination. Fairbairn, a former Shanghai police officer widely known by his nickname “Dangerous Dan.” Alongside his colleague and fellow instructor, Sykes, Fairbairn trains numerous Special Operations Executive and Office of Strategic Services agents in hand-to-hand combat, emphasising brutal effectiveness over technique or tradition. His philosophy is direct and uncompromising: “Get down in the gutter, and win at all costs… no more playing fair… to kill or be killed.” This approach becomes foundational in preparing operatives for the harsh realities of close combat behind enemy lines.

Demolitions training is particularly prominent. Explosions are frequent at the camp, not only for practical instruction but also as a deliberate form of deception. The loud blasts help to explain the facility’s true nature to the occasional local resident who might grow curious. Officially, the site appears to be an explosives testing range.

Beyond combat and sabotage, Camp X also offers instruction in more specialised areas of clandestine work. Trainees learn to forge documents, fabricate identities, and manufacture convincing cover stories. They are trained to produce and disseminate propaganda designed to undermine enemy morale or win the hearts of occupied populations. In some cases, they are even taught how to mobilise local resistance movements and irregular militias to wage guerrilla campaigns against Axis forces.

Beyond physical training, British Security Coordination also oversees technical innovation in support of espionage and sabotage. One such effort is linked to the elusive Station M, a facility responsible for the development and production of covert devices for use in field operations. Station M remains shrouded in secrecy, and its exact location is still a matter of speculation.

What seems more probable, though still unconfirmed, is that the stables of Casa Loma were used during the war for technical development, specifically, the manufacture of ASDIC sonar devices designed for anti-submarine warfare and the detection of German U-boats. Regardless of its exact location, Station M remains emblematic of the innovation and secrecy that defined British Security Co-ordination’s wartime operations.

Although the camp is run by a stiff, formal British officer, whose approach is less than popular with many Americans, it is the, at that moment, chief instructor, Major “Bill” Brooker, who becomes a central and more approachable figure. A civilian businessman before the war, Brooker is noted for his open manner, lack of pretence, and impassioned lectures. His ability to communicate with American trainees as equals makes him an effective bridge between British formality and American informality.

Brooker, although considered charismatic and highly engaging, is not without his critics. Some Office of Strategic Services personnel question his assertive style and self-promotion, especially given that he has no direct combat experience behind enemy lines. Still, others view him as a born instructor and persuasive advocate for the unconventional methods that would define the war’s clandestine front.

| Multimedia |

| Hydra |

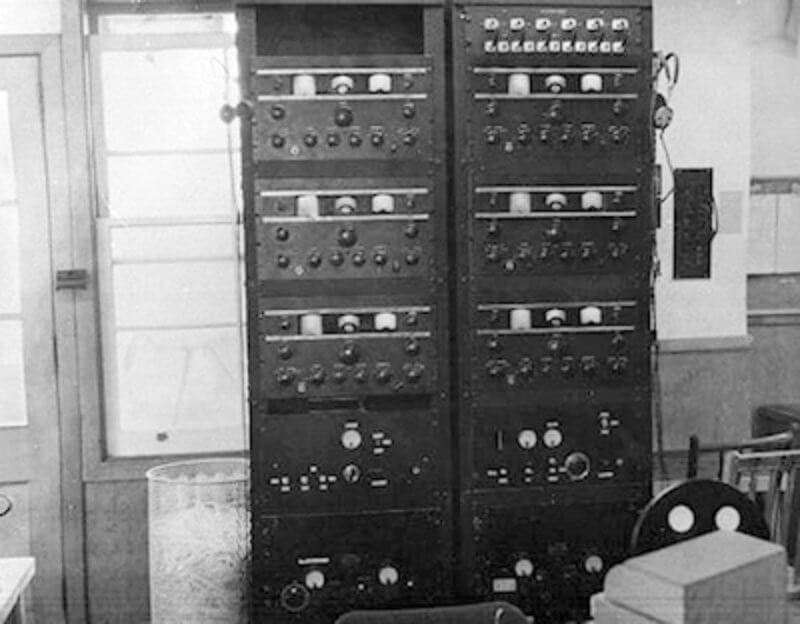

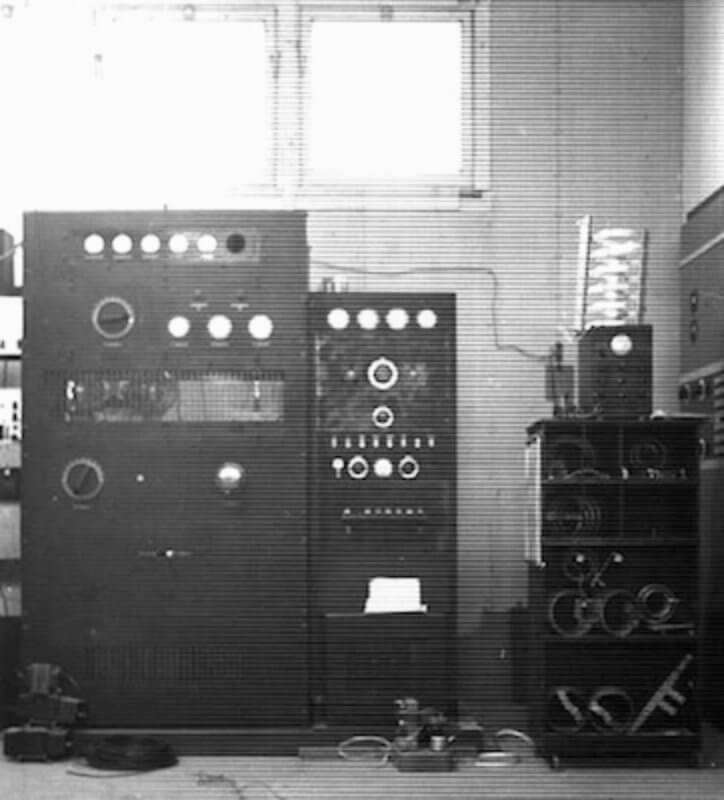

One of the most remarkable and technologically advanced elements of Camp X is Hydra, a sophisticated telecommunications relay station established in May 1942.

In the spring of 1942, large crates begin to arrive at Camp X, filled with the components of what will become one of the most advanced telecommunications facilities of the Second World War. By April, parts for the system, later codenamed Hydra, are discreetly delivered to the camp, and two men are entrusted with its construction: Bill Hardcastle and Benjamin deForest “Pat” Bayly.

Bayly, an accomplished engineer and the assistant director of Camp X with the rank of lieutenant colonel in the British Army. He works closely with Hardcastle to assemble the system piece by piece. By the summer of 1942, their efforts culminate in the full activation of Hydra, a powerful and highly secure communications relay station.

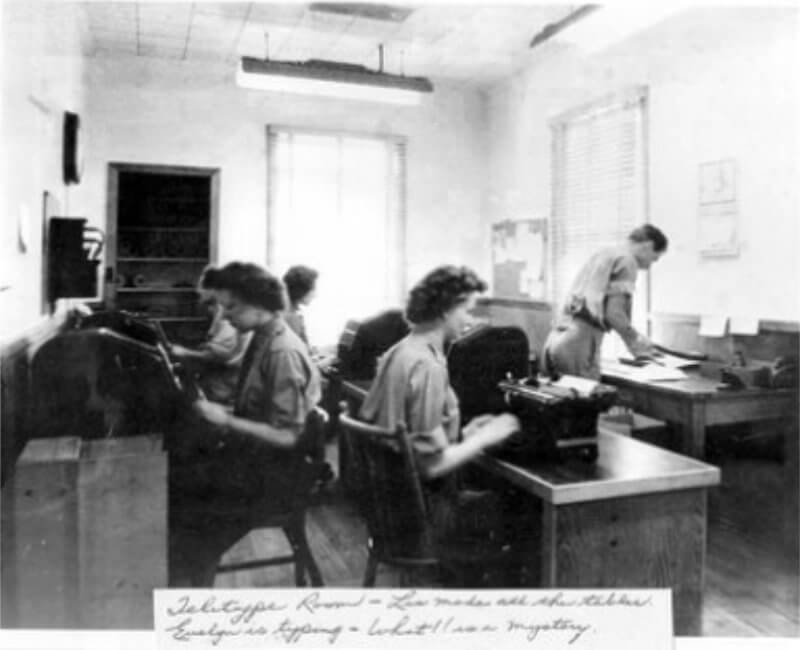

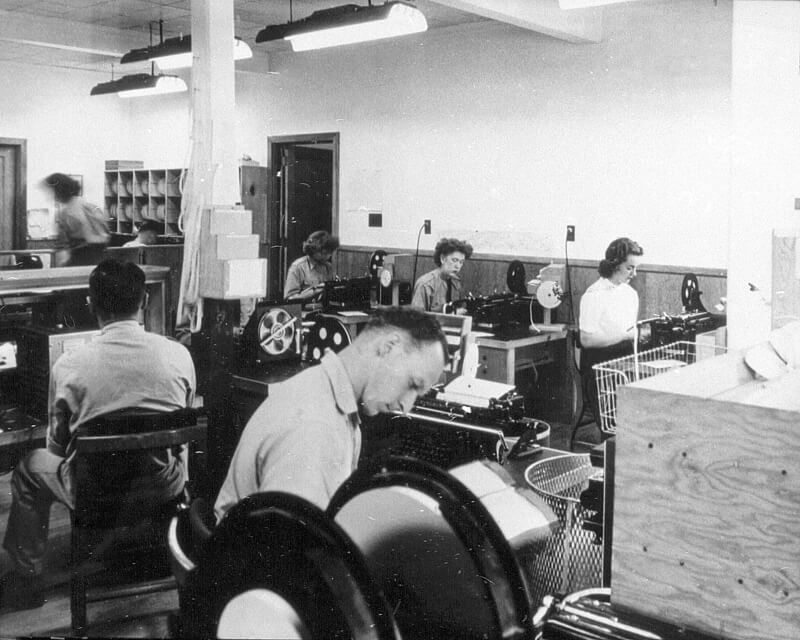

Bayly not only oversees the installation and operation of Hydra but also invents a revolutionary coding device known as the Rockex, or “Telekrypton”, a rapid, offline one-time tape cipher machine used for encoding and decoding telegraphic transmissions. This innovation significantly enhances the security and speed of Allied communications.

The placement of the facility is carefully selected for its ideal radio reception, benefiting from the topography and its proximity to both European and South American signal pathways, which often pass through the continental United States. This positioning allows the facility to intercept and transmit messages across the Atlantic with exceptional clarity. The terrain and location also make the site particularly well-suited for the secure relay of coded messages. Radio transmissions from the Great Britain are especially strong here, making Hydra an optimal listening post.

Between Thornton Road and Corbett Creek, three separate arrays of rhombic (diamond-shaped) aerials are suspended, each array strung across four telephone poles. The installation is overseen by Mr. Edmonds of Ontario Hydro, who is employed at the Camp. He is responsible for selecting the appropriate poles and supervising the construction of the system.

The rhombic configuration is chosen for its exceptional efficiency in covering a broad range of frequencies within a limited physical footprint. These aerials are notable for their high gain, indicating strong sensitivity, and for exhibiting a gradual signal fade-out, which enhances their reliability. Though still relatively new at the time, the technology proves to be both advanced and effective. To preserve the dielectric properties required for optimal function, dry air, treated with silica, is pumped through the hollow wire dipoles of each antenna.

Signals from all three rhombic arrays are channelled into a triple diversity receiver. This system combines the incoming signals into one cohesive transmission, which is then recorded as a sequence of raised dots on paper tape. Among the senior officers stationed at the Camp is a recognised authority on short wave communication and rhombic transmission theory. His duties include nocturnal calibrations, for which he routinely takes readings on the Pole Star to ensure precise alignment—an operation in which there is no margin for error.

The facility quickly becomes a key component of the broader Allied communications network. Using an array of advanced transmitters and receivers, including repurposed components from the American shortwave station W3XAU (formerly affiliated with WCAU), Hydra is capable of handling massive volumes of secure international traffic. A number of these components are discreetly acquired from amateur radio operators, delivered in pieces and assembled on-site to maintain secrecy.

Ham radio operators at Camp X play a crucial role, transmitting and receiving coded messages from Allied agents operating behind enemy lines in Europe. Hydra facilitates the constant exchange of information with London, Ottawa, New York, and Washington, D.C., thanks to direct landline connections. Through both radio and telegraph systems, it manages global Allied traffic, including communications with other Commonwealth nations.

The Canadian government later acknowledges Hydra’s significance, stating that it serves as “an essential tactical and strategic component of the larger Allied radio network.” Its ability to transmit highly classified information securely from a relatively safe location in North America shields it from the threat of German radio interception and Nazi detection. This ensures that Allied forces, intelligence agencies, and resistance networks remain connected across continents.

Hey very interesting artcle!