| Page Created |

| October 30th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| December 2nd, 2024 |

| United States |

|

| Related Pages |

| U.S. Aircraft |

| Crew |

| 2 |

| Length |

| 14.9 metres |

| Wide |

| 25.6 metres |

| Height |

| 4.7 metres |

| Weight |

| 1,770 kilograms |

| Loaded Weight |

| 4,080 kilograms |

| Propulsion |

| – |

| Armour |

| – |

| Armament |

| – |

| History |

In February 1941, following reports of the capture of Fort Eben-Emael, U.S. Army Air Forces Commanding General Hap Arnold orders the development of an assault glider, with experimental contracts for a series of prototypes to meet two separate specifications. The first requirement is for an 8-9 seat transport, and contracts are placed for single prototypes of the Frankfort Model TCC-41 as the XCG-1, the Waco NYQ-3 as XCG-3, the St. Louis XCG-5, and the Bowlus XCG-7.

The second requirement is for a larger, 15-seat glider, and the same four companies each receive contracts for a single prototype: Frankfort TCC-21 as XCG-2 (41-29616), Waco XCG-4 (41-29618), St. Louis XCG-6 (41-29620), and Bowlus XCG-8 (41-29622). Of the eight prototypes ordered, only the XCG-1, XCG-2, and XCG-6 are completed and test-flown, but no further development occurs for the St. Louis or Bowlus designs. Ultimately, only the two Waco types reach quantity production, with the CG-4 becoming the first and most widely used U.S. troop glider of World War II.

After trials with the XCG-4 in 1942, a second prototype is ordered (42-53534), and plans are made for large-scale production. The effort to establish a new military organisation, equip it with advanced technology, and train operators and maintainers becomes an urgent wartime priority, plagued with challenges from the outset. Proven American aircraft manufacturers not already engaged in government contracts for military aircraft are hesitant to participate. Some claim that their facilities are too small, while others view the concept as untested and too risky.

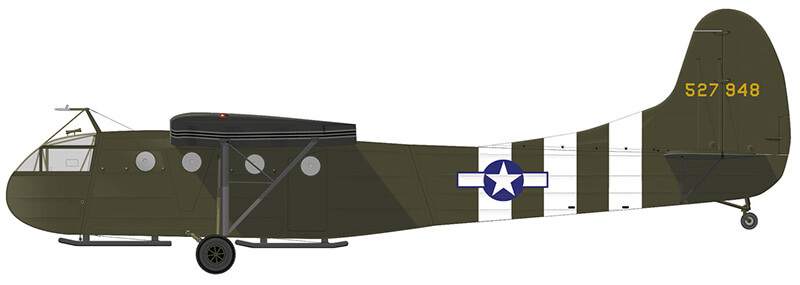

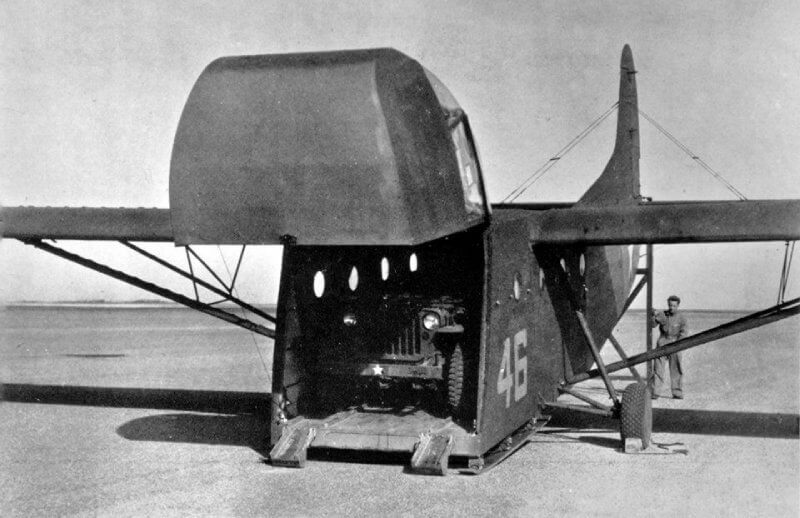

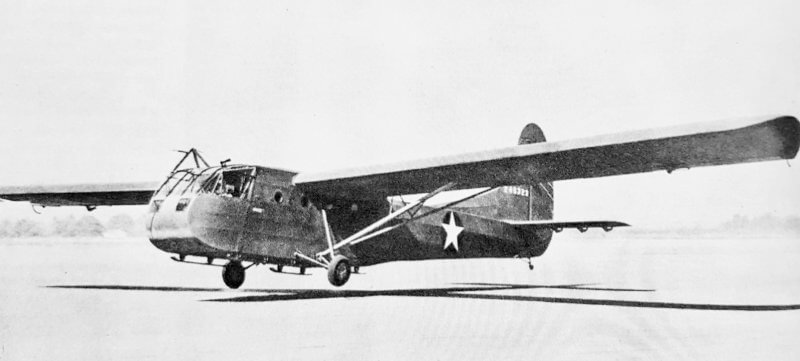

Various types and sizes of combat gliders are developed, but only the Waco Aircraft Company succeeds in producing a prototype that meets all of the Army’s structural and flight test requirements for the 15-seat workhorse, known as the CG-4A. The CG-4A is constructed from fabric-covered wood and metal, crewed by a pilot and co-pilot. It features two fixed main wheels and a tail wheel. The glider has the capacity to carry thirteen troops along with their equipment. It can also transport cargo, such as a Jeep, a 75 mm howitzer, or a half-ton trailer. Loading of the CG-4A is completed via an upward-hinged nose section, which includes the pilot’s and co-pilot’s seats and flight controls.

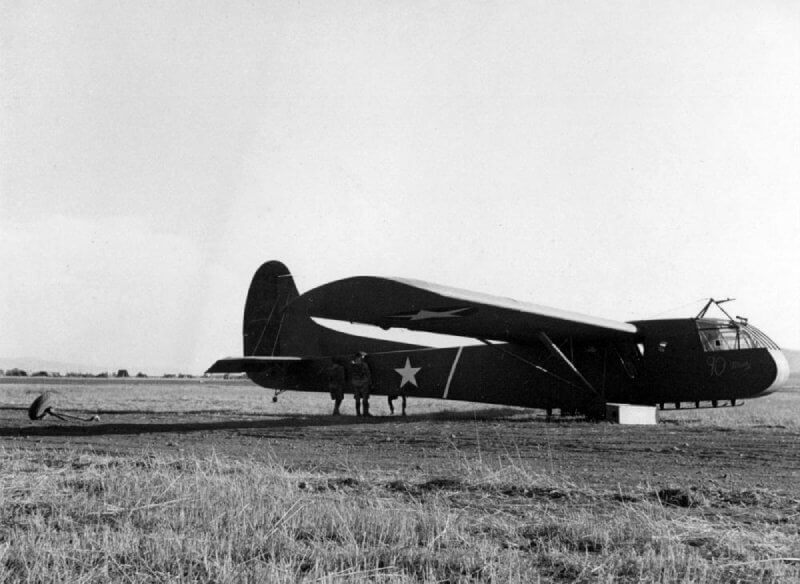

The CG-4A Waco has a wingspan of 25.6 metres and a length of 14.9 metres. The height of the CG-4A is 4.7 metres. The production model weighs 1,770 kg when empty and can fly at a maximum weight of 4,080 kg. The glider is typically towed by an aircraft such as the Douglas C-47 at speeds of up to 240 km/h. The CG-4A’s tow line is made of nylon, 107 metres long, while the pickup line is 19 mm in diameter and 69 metres long, including a doubled loop. Additionally, the CG-4A can be retrieved by a C-47 in flight using a tail hook and a grapple system.

A skilled pilot can bring the glider to a stop within a few hundred metres, depending on the load and ground conditions. Although designed to land intact for reuse in multiple airborne assaults, the realities of combat result in many gliders crash-landing, rendering them irreparable.

The CG-4A finds its niche due to its small size, which allows it to land in tighter spaces compared to the larger British Airspeed Horsa and General Aircraft Hamilcar gliders. The Horsa can carry up to 28 troops, a Jeep, or an anti-tank gun, while the Hamilcar can carry up to 7 tonnes, sufficient for a light tank.

Construction of the first CG-4A begins in 1941, with initial flights commencing in May 1942. The first glider is delivered in April 1942, and by the end of the war, nearly 14,000 are produced. Of these, 750 are handed over to the British, who name them the Hadrian.

| Production |

In total, sixteen companies are contracted to produce the CG-4A gliders:

- Babcock Aircraft Company of DeLand, Florida

- Cessna Aircraft Company of Wichita, Kansas

- Commonwealth Aircraft of Kansas City, Kansas

- Ford Motor Company of Kingsford, Michigan

- G&A Aircraft of Willow Grove, Pennsylvania

- General Aircraft Corporation of Astoria, Queens, New York

- Gibson Refrigerator of Greenville, Michigan

- Laister-Kauffman Corporation of St. Louis, Missouri

- National Aircraft Corporation of Elwood, Indiana

- Northwestern Aeronautical Corporation of Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Pratt-Read of Deep River, Connecticut

- Ridgefield Manufacturing Company of Ridgefield, New Jersey

- Robertson Aircraft Corporation of St. Louis, Missouri

- Timm Aircraft Company of Van Nuys, California

- Waco Aircraft Company of Troy, Ohio

- Ward Furniture Company of Fort Smith, Arkansas

More than 70,000 individual parts make up the CG-4A. After acceptance, some 7,000 modifications are made to the aircraft. None of these modifications are a major change and most applied to specific individual contractors to better accommodate their production facilities and methods. Factories operate 24-hour shifts to meet production demands. Ultimately, these factories produce more than 13,900 CG-4A units at an average cost of $18,800.

| Deceleration Parachute |

During the Second World War, the Waco CG-4A cargo glider plays an essential role in Allied airborne operations, but landing these gliders safely becomes a major challenge. They are required to land in confined and unpredictable landing zones, often surrounded by obstacles like hedgerows topped with tall trees. These conditions necessitate the development of a solution to improve the safety of glider landings.

Initially, glider pilots are trained in various techniques to control their descent, including using wing spoilers and side-slipping to reduce speed and lose altitude quickly. However, these methods prove risky, especially with heavily loaded gliders, making them impractical for combat landings. Recognising the need for a better solution, the U.S. Glider Branch at Wright Field, near Dayton, Ohio, begins working on an innovative idea in the autumn of 1942: a deceleration parachute designed to help gliders land more safely.

Testing of the concept starts at Clinton County Army Air Field in Wilmington, Ohio. Engineers attach a 7.3-metre air brake parachute to the tail of the CG-4A glider, inspired by earlier successful trials conducted in the 1920’s on powered aircraft. The idea is that deploying a parachute during landing will significantly reduce the glider’s ground roll, making landings much safer. Initial tests confirm that a parachute can reduce landing roll effectively, prompting further development.

In early 1943, William Milanovits, an engineer in the Parachute Branch at Wright Field, is tasked with advancing the project. He works closely with Richard duPont, who oversees the Glider Programme in Washington, D.C. Milanovits orders canopies of different sizes, ranging from 1.2 to 4.3 metres in diameter, from Reliance Manufacturing Company. Initial flight tests reveal that the larger 4.3-metre parachute nearly stalls the glider, while a 3.7-metre canopy also proves ineffective. Eventually, a 3.0-metre parachute is found to be optimal, although its initial deployment causes the glider’s tail to swing back and forth.

To solve the stability issue, a 7.6-metre leader is added between the parachute’s shroud lines and the glider’s tail. This modification helps stabilise the glider during parachute deployment, improving the safety and reliability of the system. Milanovits also designs a new parachute pack that includes a board covered in duck cloth for rigidity, ensuring the pack can be securely mounted to the glider.

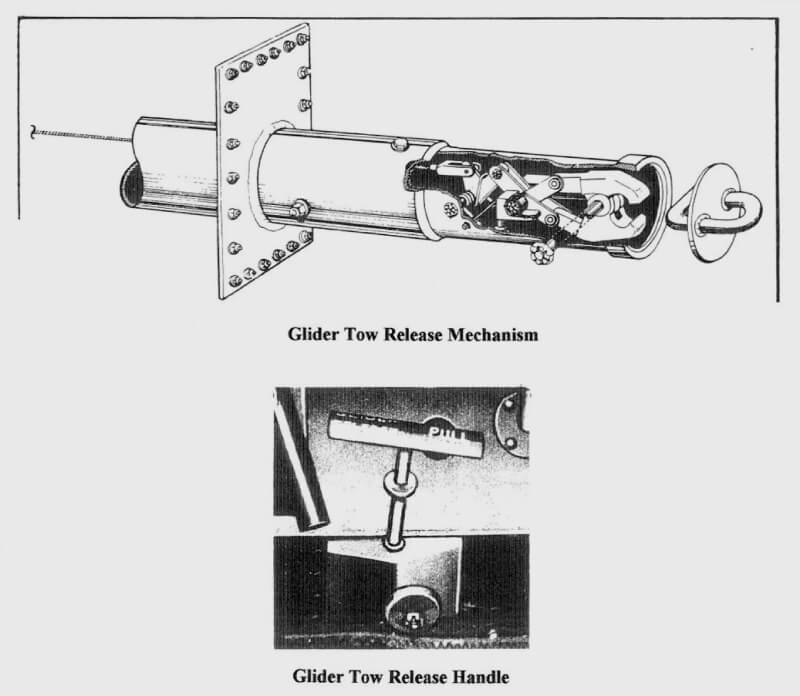

The parachute release mechanism, initially developed by Lt. Marion “Smokey” Miller, also undergoes improvements. The early design lacks bracing, as it assumes only a straight pull force when the parachute is deployed. Subsequent modifications add double tubing to the release mechanism to withstand the dynamic forces experienced during landing.

After a series of successful tests, the deceleration parachute is approved for operational use. By mid-1944, the U.S. military issues Technical Order No. 09-40CA-36, detailing the installation, inspection, and use of the parachute on CG-4A gliders. Milanovits oversees the production of 400 parachute assemblies, which are field-installed on gliders in both the United States and Europe.

The deceleration parachutes see action in several significant airborne operations. On June 6th, 1944, during the Normandy landings, several CG-4A gliders equipped with deceleration parachutes take part in the invasion. Later in September 1944, during Operation Market Garden, more CG-4A gliders make use of deceleration parachutes while landing in Holland. In March 1945, during the Rhine River Crossing, the deceleration parachutes are widely used.

Pilot opinions on the deceleration parachute are mixed. Some, like James L. Larkin and Ed Ryan, report that the parachute is effective, enabling a safe and controlled landing. Larkin, who uses the parachute in both Normandy and Rhine operations, finds it beneficial in managing the glider’s speed and stability. However, other pilots, including Sam Mitchell and William D. Knickerbocker, prefer the traditional side-slipping method, arguing that it is quicker and safer for losing altitude compared to the parachute. Knickerbocker describes instances of parachutes leading to glider crashes during training exercises, although no injuries are reported.

Despite the differing opinions, the parachute provides an added measure of safety for glider pilots and their passengers, particularly in confined and hazardous landing areas. Its successful use in operations such as the Normandy invasion, Holland, and the Rhine crossing suggests that the device plays a valuable role in enhancing the glider’s landing capabilities.

| Operational Use |

The Sedalia Glider Base is activated on August 6th, 1942, and by November, it becomes Sedalia Army Air Field (later Whiteman Air Force Base). It is assigned to the 12th Troop Carrier Command of the United States Army Air Forces and serves as a training site for both glider pilots and paratroopers. Aircraft assigned to the base include CG-4A gliders, Curtiss C-46 Commandos, and Douglas C-47 Skytrains. However, the C-46 is not used in combat as a glider tug until Operation Plunder, the Rhine crossing in March 1945.

The CG-4A sees its first operational use in July 1943 during the Allied invasion of Sicily. The gliders are flown over 720 kilometres across the Mediterranean from North Africa for nighttime assaults, such as Operation Ladbroke. Inexperience and poor conditions contribute to heavy losses. CG-4As also participate in the American airborne landings in Normandy on June 6th, 1944 and other major airborne operations in Europe and the China-Burma-India Theatre. While the Army Air Forces do not intend for gliders to be expendable, European theatre officers and combat personnel generally treat them as such, abandoning or destroying them after landing. Although equipment and methods for retrieving intact gliders are developed and sent to Europe, much of it becomes unavailable due to decisions made by higher-ranking officers. Despite this, several gliders are recovered from Normandy, with even more retrieved during Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands and in Wesel, Germany.

The CG-4A is also used to deliver supplies to partisans in Yugoslavia.

After the end of World War II, the remaining CG-4A gliders are declared surplus, with most sold off. Many are bought for their wood, while others are repurposed as towed camping trailers or used as hunting and lakeside cabins. The last recorded use of the CG-4A is in the early 1950’s by a USAF Arctic detachment supporting scientific research. The gliders are used to transport personnel to and from floating ice floes, fitted with wide skis for landing on the ice. They are towed, released for landing, and then retrieved using the hook and line system developed during the war.

| Aerial Retrieval System |

The development of the aerial retrieval system for gliders during the Second World War begins in response to the high costs faced by the U.S. Army Air Forces regarding troop and cargo-carrying gliders. In 1942, it becomes evident that abandoning gliders after a single mission is impractical due to their expense, with the CG-4A costing approximately $15,580 each, and some models costing significantly more. Given that most landing areas are unsuitable for conventional plane landings, an innovative solution for recovery is required.

To address this challenge, the Army Air Forces turn to Richard C. duPont, a 1930’s gliding champion and president of All American Aviation. DuPont’s company has previously developed a successful aerial retrieval system for picking up U.S. Postal Service mail pouches from the ground without landing. In July and September 1941, duPont and his team demonstrate to the U.S. Army Air Corps at Wright Field, Ohio, that this system can be adapted to retrieve gliders. The initial tests show the potential for aerial glider retrieval, establishing a foundation for further development.

The concept of aerial retrieval is not entirely new; the U.S. Marines use a basic retrieval system as early as 1927, employing a surplus World War I de Havilland D.H.4 biplane fitted with a trailing wire. This wire hooks a loop suspended between poles, allowing the retrieval of pouches containing dispatches. In 1939, Richard duPont partners with Dr. Lytle S. Adams, a dentist and inventor from Morgantown, West Virginia, to form All American Aviation in Wilmington, Delaware. Dr. Adams designs an aerial retrieval system in 1938 but lacks the financial resources to develop and market it; duPont, a member of the wealthy E.I. DuPont family, provides this support. Together, they modify and improve Adams’ design, eventually using a specially modified Stinson SR-10C monoplane to collect mail pouches from rural areas without requiring an airport.

To meet the Postal Service’s requirements, All American Aviation installs the AAS-4 internal cable winch, which includes a braking mechanism that functions much like a fishing reel. This cable runs through an external boom mounted on the fuselage and is connected to a hook, allowing the aircraft to pick up a nylon loop suspended between poles roughly 4 metres above the ground. When the aircraft approaches at low altitude, approximately 6 metres above the ground, it snags the loop, and the pilot then adds power to ascend, towing the retrieved object.

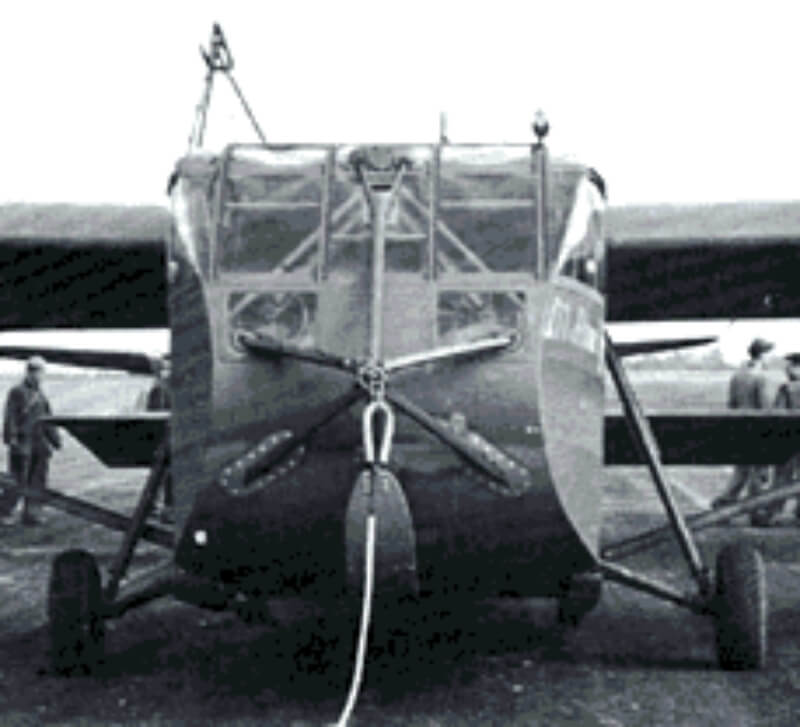

In 1941, following the success of these demonstrations, the retrieval system is tested further for military use. The AAS-4 winch system is installed in a Stinson SR-10C, and during the tests, the aircraft successfully snatches a 500 kg Midwest Utility glider containing a weighted dummy from the ground. Following these successful demonstrations, the Army Air Forces see the potential for an aerial retrieval system capable of retrieving larger gliders.

In late 1942, tests are conducted to retrieve larger gliders, including the Waco XCG-3 troop and cargo glider, using a twin-engine Douglas B-23 Dragon aircraft fitted with the new AAA Model 40 retrieval system. These successful tests lead the Army Air Forces to contract All American Aviation to develop equipment for retrieving gliders weighing between 3,600 and 7,200 kg. As a result, the Model 80 system is developed, incorporating improved braking systems to provide a controlled retrieval.

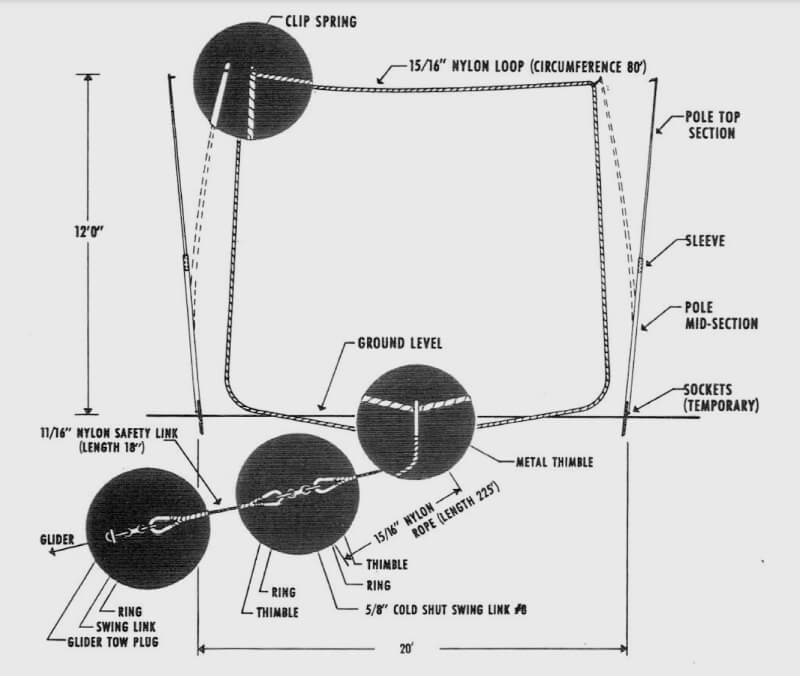

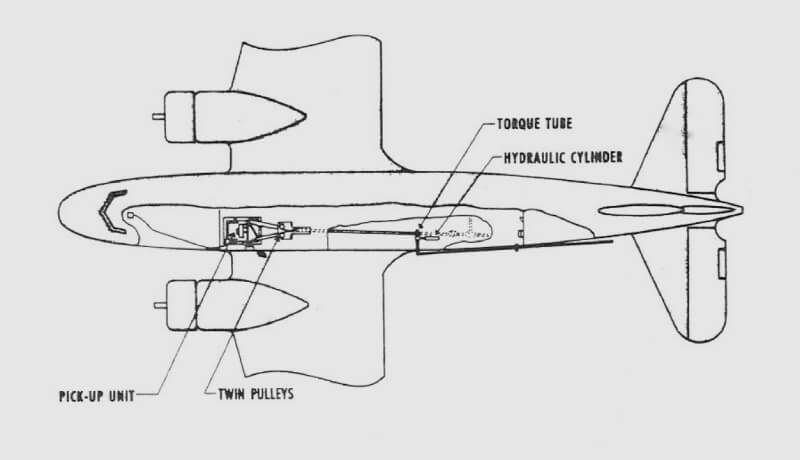

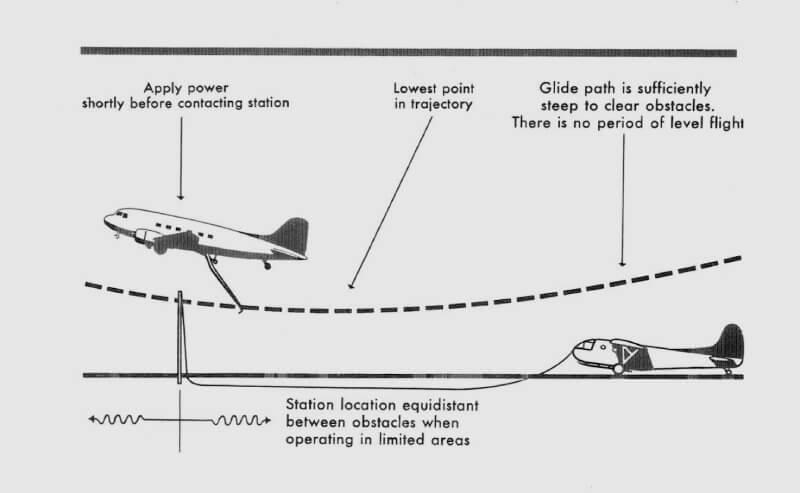

Initial testing of the Model 80 system takes place at DuPont Airport in early 1943, and subsequent primary tests are moved to Clinton County Army Air Field in Ohio. The twin-engine Douglas C-47 transport aircraft is fitted with the M-80C retrieval system to test the retrieval of Waco CG-4A gliders. These gliders are equipped with a specially designed 15-metre nylon tow rope, which can stretch by up to 30% to absorb the shock of retrieval, enabling a smooth and effective lift.

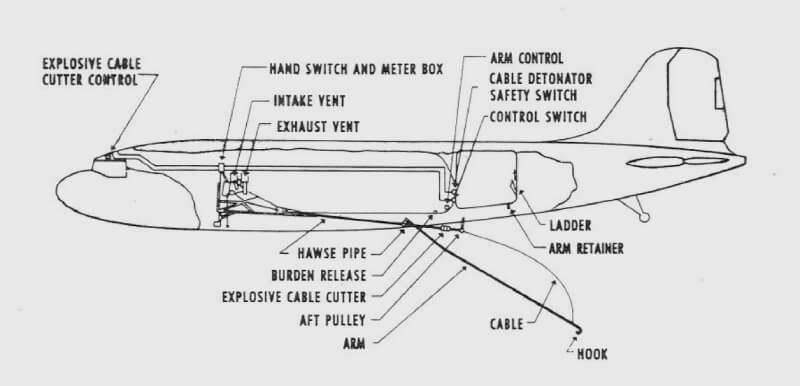

The C-47 tow aircraft is fitted with an energy-absorbing drum containing approximately 305 metres of steel cable. During retrieval, the aircraft approaches the glider at an angle, and the trailing hook snags a rope loop suspended between two poles. Once the hook engages the loop, the winch releases cable to accelerate the glider gradually, with the glider typically becoming airborne within about 60 metres and taking 7 seconds to reach flying speed.

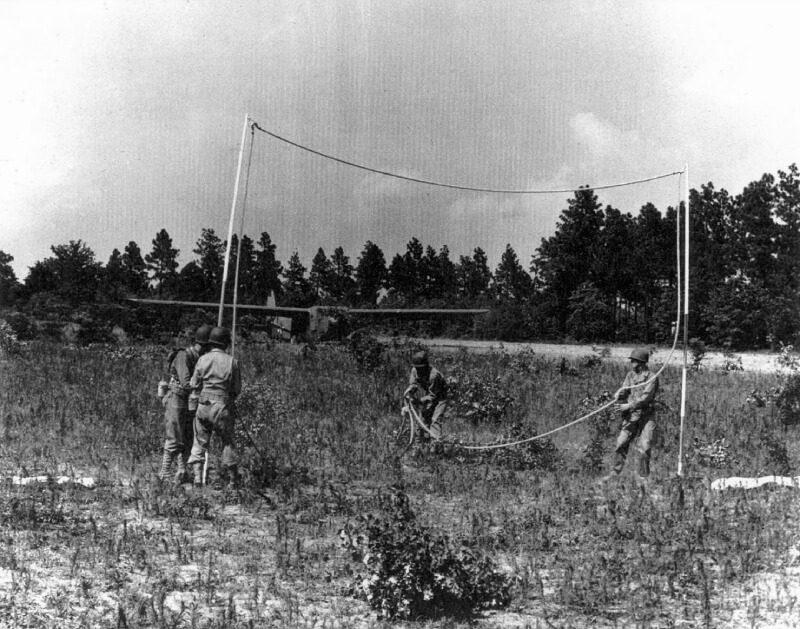

In July 1943, Major Louis B. Magid Jr. conducts further tests of the retrieval system at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In these tests, a C-47 successfully snatches a glider from the ground, demonstrating the effectiveness of the system. Additional tests involve gliders equipped only with skids as take-off gear, showing that the retrieval method places less strain on the aircraft than a conventional take-off.

Tragically, 1943 also sees the death of Richard C. duPont, who had taken up an advisory role with the Army Air Forces. In September 1943, he dies during a test flight of a glider at March Field, California. Despite this setback, duPont is posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his contributions to the war effort and the development of the aerial glider retrieval system.

The aerial retrieval system continues to evolve and sees extensive use by the U.S. Army Air Forces during the Second World War, enabling the retrieval of downed gliders from battlefields in France, Holland, Burma, and Germany. One notable mission occurs in March 1945, where two CG-4A gliders, each carrying 25 wounded American and German soldiers, are retrieved from near the Remagen bridgehead in Germany. The gliders are fitted with stretchers to accommodate the injured, and an Army nurse from the 816th Medical Evacuation Squadron, Lieutenant Suella V. Barnard, accompanies them, becoming the only nurse to participate in a glider combat mission during the war.

In May 1945, another significant mission takes place in Hidden Valley, New Guinea, where a C-47 and a CG-4A glider are used to extract survivors from a remote crash site. The survivors include two soldiers and a WAC corporal. The glider makes three separate flights to extract all the survivors and rescue personnel, highlighting the adaptability of the retrieval system for rescue missions.

Following these successful missions, experiments begin with retrieving two gliders in a single operation. The process involves the C-47 snatching one glider before circling back to retrieve a second, with the tow lines being carefully transferred between retrievals. This complex operation demonstrates the versatility and effectiveness of the retrieval system.

The aerial retrieval system ultimately proves to be instrumental in sustaining glider operations during the Second World War, making it possible to reuse gliders that would otherwise be abandoned. The retrieval process, involving the C-47 approaching at around 150 km/h and snatching a nylon loop, allows for rapid acceleration and recovery, transforming gliders from disposable assets to reusable resources. The technological advancements behind the system, including the energy-absorbing drum, adjustable friction clutch, and innovative nylon tow ropes, showcase the ingenuity required to overcome the challenges faced by airborne operations during the conflict.

By the end of the war, the retrieval system has become an essential component of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ glider operations. It is used across the European and China-Burma-India theatres, with hundreds of gliders retrieved from campaigns in Normandy, Holland, and Germany. These retrieval missions play a crucial role in ensuring the sustainability of airborne operations and demonstrate the adaptability and determination of the Allied forces in finding innovative solutions to complex challenges.

| Variations |

XCG-4 – Two Prototypes produced by WACO

CG-4A – Definitive production model; 13,903 examples

XCG-4B – One-off plywood model by Trimm

XPG-1 – One-off model with 2 x Franklin 6AC-298-N3 engines by Northwestern.

XPG-2 – One-off model with 2 x Ranger L-440-1 engines by Ridgefield.

XPG-2A – Engined model; 2 examples

PG-2A – Fitted with 2 x L-440-7 engines of 200 horsepower by Northwestern; 10 delivered during 1945.

XPG-2B – Proposed model with 2 x R-775-9 engines; never produced.

LRW-1 – United States Navy CG-4A model; 13 examples from existing U.S. Army CG-4A stocks.

G-2A – Redesignation of PG-2A in 1948

G-4A – Redesignation of CG-4A in 1948

G-4C – G-4A with revised towing equipment; 35 examples converted from existing G-4A models.

Hadrian Mk.I – British RAF designation for CG-4A; 25 examples.

Hadrian Mk II – British RAF designation for CG-4A with revised equipment fittings; 1,026 examples.

NK-4 – Czechoslovakian Air Force designation

| Multimedia |

| Manuals |

| Movies |

| WACO CG-4A |

| WACO CG-4A Hadrian |

| Glider exercise in June 1943 at Thiersville Drome and Matermore, Algeria. |

| Glider Retrieval System |