| Page Created |

| November 29th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| December 10th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Special Forces |

| 1st Airborne Division Glider Pilot Regiment Army Commandos Fallschirmjäger X Arditi Reggimento |

| Related Operations |

| Operation Mincemeat Operation Turkey Buzzard/Operation Beggar Operation Narcissus Operation Husky Operation Husky, Special Raiding Squadron Operation Husky No. 1 Operation Ladbroke Operation Ladbroke, Coup de Main Operation Husky No. 2 Operation Fustian Operation Chestnut Special Raiding Squadron, Raid on Augusta |

| Related Pages |

| Airspeed Horsa WACO CG-4A |

| July 13th, 1943 – July 17th, 1943 |

| Operation Fustian (Marston) |

| Objectives |

- Land behind enemy lines that night to capture key bridges along the road north for XIII Corps.

| Operational Area |

| Allied Forces |

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Parachute Brigade

- 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- 16th (Parachute) Field Ambulance

- 1st Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Artillery

- 1st (Airborne) Divisional Provost, Corps of Military Police

- The Glider Pilot Regiment

- 1st Parachute Brigade

- No. 3 Commando

| Axis Forces |

- 213ª Divisione Costiera

- Panzer-Division “Hermann Göring”

- 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division

- X Arditi Reggimento

| Preperations |

In the lead-up to Operation Fustian, the 1st Parachute Brigade prepares meticulously in the summer of 1943. Based in Sousse, Tunisia, their days are marked by intense training, strategic planning, and unexpected challenges.

On July 1st, 1943, the 1st Parachute Brigade begins reconnoitring training areas as company commanders are briefed on the objectives of Operation Fustian. The next day, the Intelligence Officer visits Force 141 in Carthage to gather critical information. By the end of the day, Operational Order Husky No. 14 and its administrative instructions are distributed, solidifying the operational framework.

The pace quickens on July 3rd, 1943 when two American officers deliver a lecture on escape techniques to 1st Parachute Brigade personnel, offering crucial survival insights. On July 4th, 1943, the rear party arrives from Mascara under the command of Captain Elliot, followed on July 5th, 1943 by the road party under Captain Morton, bringing additional resources.

The preparation faces a setback on July 6th, 1943, when a fire breaks out at the 1st Airborne Divisional ammunition dump. The entire dump is consumed in a massive explosion, causing significant damage and creating a chaotic backdrop to the otherwise focused preparations. Despite this, the brigade pushes forward.

On July 8th, 1943, a divisional course on new communication codes is conducted to ensure secure transmissions during the operation. The following day, General Montgomery addresses the 1st Parachute Brigade at noon, inspiring the troops as they prepare for the challenges ahead. That evening, a signal exercise codenamed Preface tests communication systems and operational readiness across all levels of command.

By July 9th, 1943, Signal Exercise Preface concludes, and the 1st Airlanding Brigade begins its journey to Sicily at 20:00 hours. The following day, final briefings are conducted, with Brigade Signals receiving their directives and consolidated parachute drop instructions being published. At 19:30 hours, Brigade Headquarters holds a final meeting to ensure all preparations are in place.

On July, 10th, 1943, Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, begins with British and Canadian forces landing on the beaches to the south of Syracuse, near the Pachino Peninsula, while American troops land further southwest near Gela. The combined air and seaborne invasion of Sicily involves a total of 180,000 American, British, and Canadian troops, supported by 3,200 ships and 4,000 aircraft, ultimately leading to Italy’s withdrawal from the war.

General Bernard L. Montgomery’s Eighth Army successfully carries out the beach landings. The Italian coastal defenders put up minimal resistance, with their coastal batteries either neutralised by naval bombardments or overrun by assault troops. By 08:00 on July 10th, 1943, the British 5th Infantry Division secures Casabile and pushes beyond Syracuse, with some troops entering the city while the main force continues advancing north along the coastal road towards Augusta.

On July 11th, 1943, they encounter Group Schmalz, a battlegroup from the 15. Panzergrenadier-Division, which is dug in at Priolo and supported by Tiger tanks and anti-tank guns, forcing the British advance to a standstill. Meanwhile, the British 50th (Northumbrian) Division under Major-General Sidney C. Kirkman lands at Avola and proceeds quickly north towards Casabile, while XXX Corps, composed of Highlanders and Canadians, moves inland against light opposition. The Malati bridge over the Leonardo River and Primosole Bridge across the Simeto River hold significant importance for the advance of British forces from the southeastern beaches towards Catania.

Montgomery arrives in Syracuse, finding the port nearly intact, and sets up his tactical headquarters after arriving from Malta. He is eager to initiate Operation Fustian. Operation Faustian is the capture of the the Malati and Primosole Bridges.

That very same say in Sousse, Tunisia, the 1st Parachute Brigade undergoes an inspection in full G1098 equipment. Life belts are distributed, and practice firing drills are conducted. Containers are meticulously loaded and checked to ensure readiness. By 22:00 hours, all personnel are ordered to rest, knowing the operation is imminent.

On July 12th, 1943, the day begins with a structured routine of reveille, breakfast, and final Royal Air Force briefings. By mid-afternoon, the 1st Parachute Brigade moves to the airfield, but upon arrival, they are informed of a 24-hour postponement. The brigade returns to camp, leaving their equipment ready on transport vehicles.

The following day, July 13th, 1943, the 1st Parachute Brigade receives confirmation that Operation Fustian will proceed that night. At 15:45 hours, the unit departs for the airfields. Intelligence reports suggest that the 50th Infantry Division will advance northward toward Catania, aiming to link up with the airborne forces at first light.

That very same day, Lieutenant Colonel John Durnford-Slater, commander of No. 3 Commando is summoned to XIII Corps headquarters in Syracuse, to receive orders for Operation Fustian. He meets General Montgomery, Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey (commander of XIII Corps), and Admiral Rhoderick McGrigor near the quayside by the old Italian naval officers’ quarters.

Durnford-Slater is concerned about the limited time available to plan the Agnone landing, but intelligence reports suggest that the Malati Bridge is only held by a small Italian force. Montgomery remains optimistic, stating, “Everybody is on the move now. The enemy is nicely on the move. We want to keep him that way. You can help us do that. Good luck, Slater.”

| Operational Planning |

This operation is assigned to No. 3 Commando and the 1st Parachute Brigade, who are to land behind enemy lines that night to capture key bridges along the road north for XIII Corps. The Commandos plan to land from the sea near Agnone, advance inland, and secure the Ponte dei Malati Bridge over the River Leonardo. Meanwhile, 1,856 paratroopers from the 1st Parachute Brigade will drop from the air to capture the Ponte dei Primosole Bridge, the only bridge over the River Simeto, located eight kilometres to the north. Securing these bridges will open the route towards Catania and prevent the enemy from establishing defensive lines along the two rivers.

In 1943 each Commando comprises a small headquarters group, five troops, a heavy weapons troop, and a signals platoon. The fighting troops consist of 65 men of all ranks, divided into two sections of 30 men each, with each section further divided into three subsections of 10 men. The heavy weapons troop includes teams operating 3-inch mortars and Vickers machine guns.

The 1st Parachute Brigade, led by Brigadier Lathbury, consists of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Parachute Battalions, along with the 16th (Parachute) Field Ambulance, the 1st (Parachute) Squadron of the Royal Engineers, and the 1st (Airlanding) Anti-Tank Battery of the Royal Artillery. The airlanding anti-tank battery is equipped with the brigade’s only anti-tank weapons, the British 6-pounder guns. Although the formation is designated as a parachute brigade, the anti-tank guns and the jeeps needed to tow them after landing can only be transported by glider.

The plan for the 1st Parachute Brigade involves deploying paratroopers across four separate drop zones, with gliders landing at two designated landing zones. The 1st Parachute Battalion is divided into two groups, with one landing at Drop Zone One north of the river, and the second group landing at Drop Zone Two to the south. Upon landing, both groups are to head to their respective assembly points before launching a coordinated assault on the bridge from both sides simultaneously.

The 2nd Parachute Battalion is assigned to Drop Zone Three, located south of the bridge, between the Gornalunga Canal and the main highway. The battalion’s objective is to assault and occupy three small hills, codenamed Johnny I, Johnny II, and Johnny III. Intelligence suggests these hills are held by an Italian platoon-sized force. Once secured, the battalion is to dig in and prepare to defend the hills against attacks from the south.

The 3rd Parachute Battalion is tasked with landing at Drop Zone Four, approximately 900 metres north of the bridge. Their mission is to secure the surrounding area and prevent any counterattacks originating from Catania.

The addition of D Troop and an expanded Battery Headquarters was a last-minute decision, made possible by the cancellation of another operation, Operation Glutton. This allowed for the inclusion of more tug aircraft, enabling additional gliders to join the mission. In total, 19 gliders, 11 Airspeed Horsa’s and 8 Waco CG-4A’s, were loaded with 12 anti-tank guns, jeeps, and essential equipment. The gliders were designated for two Landing Areas: Landing Zone Seven north of the river, and Landing Zone Eight south of the river.

Each team of gunners underwent meticulous preparation. Jeeps and guns were secured within the gliders, while crews rehearsed unloading procedures. The task ahead was daunting: land in enemy territory, unload heavy equipment under fire, and immediately join the fight.

The brigade’s glider force is allocated two landing areas, Landing Zone Seven north of the river, and Landing Zone Eight south of the river. Given the complexity of the plan and the limited time available between planning and execution, the 21st Independent Parachute Company, Army Air Corps, is tasked with marking the correct drop zones. This represents the first use of pathfinders in a British airborne operation. The pathfinder company is equipped with special marker lights, as well as Rebecca and Eureka beacons, which can be identified by both the transport aircraft and the gliders to ensure accurate landings.

The use of gliders to transport artillery into combat is a new concept for the British Army, and indeed any other military force. This operation marks the first occasion in which artillery pieces are flown directly into battle.

It is expected that the medical officers and staff from the three parachute battalions alone would be unable to manage the anticipated number of casualties. Therefore, a section from the 16th (Parachute) Field Ambulance, comprising one doctor and 16 other ranks, is assigned to support each of the parachute battalions. The remainder of the field ambulance unit, including the headquarters and two surgical teams, is stationed with the brigade to set up the main dressing station in farm buildings located south of the bridge.

The airborne operation involves a combination of aircraft, including 105 Douglas C-47 Skytrains provided by the 51st Troop Carrier Wing. Of these, 51 aircraft come from the 60th Troop Carrier Group, another 51 from the 62nd Troop Carrier Group, and three from the 64th Troop Carrier Group. Additionally, No. 38 Wing of the Royal Air Force supplies eleven Armstrong Whitworth Albemarles.

Following the parachute forces are the glider-towing aircraft, also provided by No. 38 Wing. These consist of 12 Albemarles and seven Handley Page Halifaxes, towing 11 Airspeed Horsa gliders, Nos. 119 – 129 and eight WACO CG-4A gliders, Nos. 114 – 118(c). The gliders are used to transport seventy-seven personnel, mostly from the anti-tank battery, along with ten 6-pounder anti-tank guns and eighteen jeeps.

The landings for No. 3 Commando are planned in two waves of Landing Craft Assault from the Landing Infantry Ship H.M.S. Prince Albert. Troops 1 and 3 from the first wave in Landing Craft Assaults will advance immediately to take the bridge. The remaining troops will hold the beach while awaiting the second wave. Once reinforced, additional troops will move inland, with 4 Troop sending patrols to make contact with the paratroopers at Primosole Bridge.

The relief force for both No. 3 Commando and the 1st Airborne Brigade is drawn from British XIII Corps, under the command of Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey. XIII Corps comprises the 5th Infantry Division, the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, and the 4th Armoured Brigade. The armoured brigade, equipped with American-built Sherman tanks, includes three tank regiments.

| Operation Faustian, No. 3 Commando |

At 21:30, H.M.S. Prince Albert, having earlier evaded an attack by an E-boat, begins lowering assault boats carrying No. 3 Commando. As the boats approach the shore, the scene is chaotic. To the north, Catania is under heavy bombardment. The sky to the west is criss-crossed by tracer bullets and very lights, while to the south, anti-aircraft fire and star shells illuminate the area around Syracuse. Overhead, Dakotas and glider tows roar towards Primosole.

When the boats are about 180 metres from shore, German forces open fire, and the Commandos return fire as best they can from their rocking craft. With the near collapse of the Napoli Division the previous day, the entire Axis line is at risk of disintegration, prompting the deployment of troops from the Panzer-Division “Hermann Göring” and 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division to reinforce the front.

The Commandos swiftly overcome two pillboxes on the beach. Major Peter Young gathers Troops 1 and 3 and advances quickly towards the bridge, situated eight kilometres inland.

The terrain proves challenging to navigate at night, covered in dense cacti, shrubs, vineyards, and intersected by deep streams. However, progress becomes easier once the troops locate the railway line leading to Agnone railway station and continue towards their objective. Along the way, they encounter a group of British paratroopers who have landed well south of their target. The Commandos invite them to join, but the paratroopers decline, opting to continue north to try and reach Primosole Bridge. By 03:00, Major Young and his troops reach the northeast end of the Malati Bridge over the River Leonardo, a bridge spanning 230 metres.

The pillboxes defending the bridge, manned by Italian forces, are quickly neutralised with grenades through the loopholes, and the demolition charges on the bridge are removed. The Commandos then establish defensive positions around the bridge, deploying through orange groves and shallow ravines, using rocks to build defences as the ground proves too hard to dig into.

The second wave is delayed reaching the beach, as the Landing Craft Assaults returning from the first wave lose their way back to the ship. Reloaded with additional troops, they come under fire during the approach to the beach. However, the escorting destroyer, H.M.S. Tetcott, uses smoke shells to blind the defenders positioned on the cliffs. By dawn, Durnford-Slater has between 200 and 300 men in position, armed with light platoon weapons.

However, heavier German units soon join the fight. A Tiger tank begins shelling the bridge, damaging the pillboxes and bombarding the thin cover the Commandos are using. Casualties begin to mount. The Commandos come under increasing pressure with the arrival of daylight. A PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank) on the bridge manages to destroy a German ammunition truck, resulting in a spectacular explosion.

During the morning, additional German tanks arrive, accompanied by three battalions from a panzer grenadier regiment, as well as an Italian contingent of tanks and infantry.

By 05:20, Durnford-Slater holds a brief meeting with Major Peter Young and acknowledges that they are quickly losing control of the situation. There is still no sign of the 50th Infantry Division, and casualties from mortar and tank fire are steadily increasing.

More Commandos arrive from the beach. Captain Pooley attempts to flank the enemy with Troops 5 and 6 but is driven back by intense fire; the Tiger tank is the primary cause of the Commandos’ difficulties. Positioned among cypress trees on the opposite side of the bridge, nearly hull-down, it is out of range of the PIATs, and advancing across open ground towards it is suicidal.

Vastly outnumbered and with almost a third of his men killed or wounded, Durnford-Slater has no choice but to order his surviving troops to break into small groups and make their way back to British lines. Most manage to do so, though a few isolated groups continue fighting, keeping the bridge under fire.

More than 150 officers and men are dead, wounded, or missing from No. 3 Commando, but they succeed in holding the Malati Bridge and removing the demolition charges, ensuring it remains intact when the 50th Infantry Division finally reaches it.

| Take off and Landing 1st Parachute Brigade |

By 19:20 hours, the 1st Parachute Brigade begins its take-off. The flight path for the aircraft takes them around the southeastern tip of Malta, proceeding along the eastern coast of Sicily. The route is carefully calculated to ensure that the first planes arrive over the designated drop zones at 22:20. Upon reaching the coast of Sicily, the aircraft are meant to stay approximately 16 kilometres offshore until reaching the Simeto River, at which point they would head inland to the drop zones.

As the lead planes pass over Malta at 21:30 hours, the tension is palpable. Flak from a convoy traveling toward Sicily briefly disrupts the journey, but the brigade remains focused. The stage is now set for one of the most critical operations of the Allied campaign, with the men of the brigade prepared to face whatever challenges lie ahead.

During the flight in, 33 of the aircraft deviate from their planned course and approach an Allied convoy. The naval gunners, having been warned of a potential air raid, mistakenly open fire on the incoming American and British planes. In the chaos, two aircraft collide while trying to evade the unexpected anti-aircraft barrage, crashing into the sea. Another two planes are shot down, and nine are severely damaged, forcing them to return to their North African airfields with wounded crew and paratroopers. One of the aircraft carrying No. 4 Section, 16th Parachute Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps is mistakenly targeted and shot down by the merchant vessels, presumed to be a torpedo bomber. Four personnel from the aircraft are reported missing, while the survivors are rescued by a naval destroyer. Anti-aircraft fire (flak) over the drop zones is heavy, further dispersing the units.

Those aircraft that reach the Sicilian coast encounter heavy Axis anti-aircraft fire, resulting in 11 planes being shot down. Another ten are damaged and have to abort the mission. Some inexperienced pilots, shaken by the barrage, refuse to proceed any further. On his aircraft, Lieutenant Colonel Alastair Pearson, commanding officer of the 1st Parachute Battalion, realises that the plane is circling aimlessly and is forced to threaten the crew to continue the mission.

The anti-aircraft fire and subsequent evasive actions cause the aircraft formations to become dispersed, leading to a scattered parachute drop over a large area. The erratic manoeuvring leaves some paratroopers in disarray, unable to jump when ordered. Once safely over the sea again, some pilots refuse to make another attempt, deeming the risk unacceptable. Of the aircraft that continue with the mission, only 39 manage to drop their paratroopers within 800 metres of the intended drop zone.

At 22:14, the leading aircraft brave the flak, and the Commanding Officer of the 2nd Parachute Battalion, along with part of Battalion Headquarters, successfully descends onto Drop Zone No. 3. The chaotic environment underscores the high stakes of the operation.

The most off-course landings involve groups from the 3rd Parachute Battalion and the Royal Engineers, who land approximately 19 kilometres south of the bridge. Additionally, four aircraft drop their paratroopers on the slopes of Mount Etna, roughly 32 kilometres to the north. Captain Victor Dover, adjutant of the 2nd Parachute Battalion, and his group are dropped there. Dover and another soldier take a month to find their way back across country to Allied lines, while the rest are captured. It is a rough experience for the men crammed into the violently twisting aircraft, and some are released at altitudes too low, resulting in severe injuries. Less than 20 percent of the brigade lands in the correct locations, with an additional 30 percent returning to base. It is later confirmed that only 12 officers and 283 other ranks take part in the battle.

By 22:30 hours, the first elements of the 1st Parachute Battalion begin their descent, adding to the growing presence of airborne forces on the battlefield. The paratroopers of the 1st Parachute Brigade that land on the southern drop zone find themselves well within the range of the 1. Fallschirmjäger-Maschinengewehr-Bataillon. Initially, under cover of darkness, the Germans mistake the British paratroopers for their own reinforcements, but they soon realise their error and open fire. Some paratroopers who escape the machine gun fire are captured on the drop zone, resulting in approximately 100 becoming prisoners of war as soon as they land.

Of the 16th Parachute Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps, Captain Keesey’s No. 3 Section lands far from their objective, astride a river 5 kilometres west of the bridge. Under heavy fire, they scramble to recover equipment. A wheeled stretcher is rendered useless by flak damage, and the team struggles to move forward.

On the evening of July 13th, 1943, as dusk fell over Tunisia, the gliders take off in staggered groups from Strips E and F. Between 21:45 and 22:00 hours, the last of the 11 Airspeed Horsa’s lift into the air. Horsa No. 125 damages his tow rope on take off and is unable to continue. On strip F the WACO CG-4A’s take off in the same time period. The WACO glider losses also occur during take-off, when two aircraft towing Waco gliders Nos. 115 and 118 crash. While en route, one of the gliders is prematurely released by its towing aircraft, resulting in a crash into the sea.

The remaining gliders press on, their tug aircraft climbing to a cruising altitude of over 500 metres. As they near Sicily, the tranquility of the Mediterranean night shatters. Searchlights sweep the sky, and anti-aircraft fire erupts, forcing the tugs into evasive maneuvers. The carefully planned routes are disrupted as aircraft weave through the flak, with many losing their bearings.

As the coastline comes into view, confusion among the navigators became apparent. Many mistake the River Leonardo for the Simeto, leading to widespread dispersion. From the ground, parachute troops observe gliders circling aimlessly, some veering inland, others heading back out to sea. Orders to release are eventually given, but the result was a scatter that covered an area 16 kilometres long and 10 kilometres wide.

Two hours have passed since the initial parachute landings. One glider pilot later remarks that the lights from tracer fire and explosions are far brighter than any of the pathfinders’ landing markers. Out of the surviving glider force, only four gliders, carrying three anti-tank guns, manage to land without significant damage, while the remainder is destroyed by machine gun fire from the Fallschirmjäger during their approach.

Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 119, reports suggest this glider came down in flames, with no further information available about its crew or cargo. Its fate remains unknown. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 120, landed approximately 600 metres west of Landing Zone 8. While its undercarriage was damaged, the jeep and anti-tank gun were intact. No opposition was encountered upon landing, and the crew joined the 2nd Parachute Battalion. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 121, no communication was received from this glider. Its location and fate remain uncertain. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 122, landed but came to rest in a position that made unloading impossible. Despite slight opposition, the detachment successfully joined a Commando unit. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 123, landed, with both the jeep and gun intact. The glider was surrounded by enemy forces, forcing the detachment to lay low during the day before making their way to Lentini under the cover of darkness. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 124, like Glider 121, no reports were received about its landing or subsequent activity. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 125, did not take off due to a damaged tow rope. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 126, successfully landed on Landing Zone 8, albeit under heavy fire from the nearby bridge. Despite damage to the glider, the jeep and gun were operational, and the detachment moved into position south of the river. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 127, crashed. The glider was completely destroyed, resulting in four fatalities and three injuries among the crew. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 128: Crash-landed in the river near Landing Zone 8. Of the crew, four were killed, two were injured, and one survived unscathed. The status of the jeep and gun remains unknown. Airspeed Horsa Glider No. 129: Landed near the bridge at Landing Zone 8 under fire. Despite damage to the glider, the jeep and gun were intact. The detachment joined the 2nd Parachute Battalion.

The Waco’s fare no better. Glider 114: Initial reports indicate it landed, but no further details are available. WACO CG-4A Glider No. 115, cast off shortly after takeoff and did not reach Sicily. WACO CG-4A Glider No. 116, landed near the outer defenses of Catania Aerodrome. The gun was immobilized due to damage sustained under fire, and the detachment withdrew to the bridge. WACO CG-4A Glider No. 117, landed. Both the jeep and crew were unharmed despite landing within enemy-held territory. The detachment regrouped at Lentini the following night. WACO CG-4A Glider No. 118, cast off shortly after takeoff and failed to reach its destination. WACO CG-4A Glider No. 118(a), landed on the beach. The glider’s nose jammed on impact, preventing the removal of the jeep. The crew was captured but later escaped. WACO CG-4A Glider No. 118(b), no reports were received about its landing or activities. WACO CG-4A Glider No. 118(c), crash-landed. The glider sustained severe damage, with all crew members injured. The jammed nose prevented the jeep from being unloaded.

Summary of Glider Landings

| Type | Crossed Tunisian Coast | Landed (Unload Possible) | Landed (Unload Impossible) | Crashed Completely | Unaccounted For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horsas | 10 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Wacos | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Operation Faustian, 1st Parachute Brigade |

Together with his batman, Private Lake, Brigadier Gerald Lathbury, the brigade commander, heads towards the Primosole Bridge in the darkness, having been dropped five kilometres away. He jumps with his group at 23:30 from a height of about 60 metres. Fortunately for Lathbury, he lands on soft, ploughed ground. On their way, the two men briefly pause to collect weapons from a supply container, where they meet other members of the brigade headquarters.

Further along, they encounter Lieutenant Colonel Johnny Frost and 50 men from his 2nd Parachute Battalion, also making their way to the objective. Lathbury divides his force into four sections, but upon reaching the vicinity of the bridge.

At 01:00 hours, a Headquarters party from the 3rd Parachute Battalion establishes contact with elements of the 1st Parachute Battalion, as well as a small number of their own men. The 1st Parachute Battalion group immediately sets off toward the bridge, driven by the urgency of their mission.

By 01:30 hours, the 3rd Parachute Battalion party reaches the bridge area and reunites with the 1st Parachute Battalion. The bridge looms ahead as both units converge on their shared objective. At 02:00 hours, Second Lieutenant Lazenby of the 1st Parachute Battalion is tasked with sending a patrol of seven men to reconnoitre the bridge, while the Intelligence Sergeant of the 3rd Parachute Battalion is dispatched to establish contact with Brigade Headquarters.

At 02:15 hours, Captain Rann and Second Lieutenant Lazenby lead a small force, approximately 7% of the 1st Parachute Battalion, in an assault on the bridge. Their bold attack is successful, and they secure the structure. Meanwhile, a detachment from the 2nd Parachute Battalion moves toward their Forming-Up Point.

By 03:15 hours, 1st Parachute Brigade Headquarters party arrives at the southern end of the bridge, preparing for an assault. To their surprise, the bridge is already in British hands. However, the Brigade Commander is wounded by a grenade thrown by a stray Italian soldier. At 03:30, approximately 50 Prisoners of War are rounded up in the bridge area and confined to buildings north of the bridge. Nearby, three sticks of A Company from the 2nd Parachute Battalion, joined by 12 men from B Company, organise into a single platoon of 45 men. They launch an attack on Objective J.1, capturing it after a fierce exchange of grenades and small arms fire. Along with the objective, they take approximately 100 prisoners.

By 04:00 hours, the main party of the 2nd Parachute Battalion arrives at the F.U.P., discovering an unoccupied pillbox. The bridge is now fortified with 120 men from the 1st Parachute Battalion and two platoons from the 3rd Parachute Battalion. A Force Headquarters is established at the bridge, though wireless communication remains unavailable.

By 04:30, the 1st Parachute Battalion has already secured the Primosole Bridge, but elements of the 1. Fallschirmjäger-Maschinengewehr-Bataillon are firmly entrenched to the south. Their available support weaponry consists of only three anti-tank guns, two 3-inch mortars, and a single Vickers machine gun.

The Brigade Headquarters and the main dressing station for the field ambulance are established to the south of the bridge, where casualties from the brigade begin to arrive for treatment. Away from the main dressing station, medics at the 2nd Parachute Battalion’s drop zone deal with 29 wounded personnel as a result of the parachute drop, while 15 wounded are reported at Drop Zone One from the 1st Parachute Battalion.

Around 04:30, a patrol of 50 men from the 2nd Parachute Battalion heads to reconnoitre Objective Johnny 1, linking up with the composite platoon already in position. Major Lonsdale takes command of the combined forces, solidifying their hold on the objective. By 05:00, the position is consolidated, and the 2nd Parachute Battalion establishes its headquarters, bringing the total force in the area to 120 men. Lieutenant Colonel Johnny Frost positions his men on high ground overlooking the bridge, while Brigadier Lathbury deploys another 40 men along both sides of the river.

The situation at the bridge is dire but manageable by 05:30 hours. The defenders include 120 men from the 1st Parachute Battalion, supported by two 3-inch mortars, a Vickers machine gun, and three PIATs. Wireless communication is limited to a single No. 22 Radio set. The 3rd Parachute Battalion’s two platoons lack support weapons or wireless capability, while the 2nd Parachute Battalion holds Johnny 1 with 120 men but no support weapons or wireless communication.

Meanwhile, Captain Ridler of the 16th Parachute Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps , meanwhile, leads his stick to a farm designated as the Main Dressing Station. Overcoming resistance from a small group of Italian soldiers, he secures the location and begins preparing for incoming casualties.

On the high ground southwest of the bridge, Lieutenant Colonel Wheatley of the 16th Parachute Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps and his stick encounter wounded men along their march. Unable to transport them further, they provide what aid they can before pressing on. By 05:45, Wheatley arrives at the bridge, now held by Allied forces. He receives word that the Main Dressing Station is operational and cycles to the site, taking command of the medical efforts.

At 06:15, 1st Parachute Brigade Headquarters is established on the southern riverbank, though wireless sets remain non-functional. By 06:30, defensive positions at the bridge are reinforced with 6-pounder anti-tank guns brought in by glider, along with captured enemy anti-tank gun. Sergeant Anderson positions his gun south of the river, covering a critical road. Lance Sergeant Atkinson’s gun is directed at a key approach route, while Sergeant Doig’s detachment secures the flank.

Second Lieutenant Clapham, upon landing, works tirelessly to assist with unloading and positioning the guns. In a stroke of ingenuity, he commandeers two captured Axis anti-tank guns from nearby pillboxes, instructing glider pilots and parachute troops in their use. An additional 120 men have reached the bridge, where the battle is already underway. With the men from the gliders included, the 1st Parachute Brigade now has 295 personnel at the bridge.

While this is going on, a counterattack develops at Johnny 1, supported by Italian machine guns and mortars. Communications within the brigade remain compromised. Beyond their position, approximately 140 men from the 2nd Parachute Battalion occupy the three small hills and have taken 500 Italian prisoners. In terms of numbers, both battalions are reduced to little more than company strength.

The 3rd Parachute Battalion suffers the worst losses during the scattered parachute drop, and only a small number of their men manage to reach the bridge. Lacking a cohesive command structure, they are attached to the 1st Parachute Battalion to assist in defending the bridge.

To the north, the Italian 372nd Coastal Battalion and the 10th Arditi Regiment are alerted to the British parachute landings. Many members of the 372nd Battalion desert their positions, while the Arditi launch the first of several attacks on the British positions. However, lacking the support of heavy weaponry, their attacks are easily repelled.

The Germans have set up barbed-wire roadblocks at both ends of the bridge but open them to allow a truck towing a field gun to pass just as the British assault party charges in. During the ensuing firefight, Brigadier Lathbury is hit by a grenade, sustaining several shrapnel wounds.

When the sappers arrive, they find the brigadier with his trousers down, bent over as dressings are applied to his injuries. As the only sapper section to reach the bridge, they are ordered by Brigadier Lathbury to remove the demolition charges as quickly as possible.

The Italian pillboxes at either end of the bridge contain useful weapons, including several Breda heavy machine guns, which the paratroopers quickly turn against their former operators. Positioned to cover the roads are two Italian 50 millimetres guns and one German 75 millimetres anti-tank gun in concrete emplacements, which are also used to reinforce the paratroopers’ defence.

Towards the morning, a desperate battle is unfolding at the Primosole Bridge over the Simeto River, where the airborne troops have stirred up a hornet’s nest and are facing increasing enemy pressure. The British paratroopers hold both ends of the bridge, fighting off relentless infantry attacks with rifles and Bren guns while being bombarded by artillery and mortar fire and strafed by Focke-Wulf 190 fighter bombers. Repeatedly, the Germans attempt to storm the bridge.

Sergeant Anderson’s gun silenced an enemy pillbox, allowing paratroopers to regroup south of the bridge. At the same time, heavy fire from enemy positions targeted the newly deployed guns.

Driver Reed, with remarkable composure, used his jeep to ferry ammunition and evacuate wounded soldiers. The road was under constant fire, but his relentless efforts ensured the continued defense of the bridge.

After the heavy losses suffered by German airborne forces during the invasion of Crete in May 1941, Hitler had decreed no more airborne assault landings. However, local German commanders in Sicily decide to disregard the Führer’s order and call for a parachute drop by the 4. Fallschirmjäger Regiment at the Primosole Bridge.

Gradually, the German Fallschirmjäger of the 4. Fallschirmjäger Regiment, who have been accurately dropped into the area an hour before the British landings, work their way close to the bridge, moving into the reed-covered banks of the river.

On three hills overlooking the southern approaches to the bridge, Lieutenant Colonel Frost and approximately 140 men from the 2nd Parachute Battalion are attempting to hold off an increasing number of enemy forces retreating from the advancing 50th Infantry Division.

The battle intensifies at 07:00 hours, as a Main Dressing Station is established. Colonel Wheatley oversees the setup of an operating theatre. Italian soldiers surrender near the bridge, emerging from hidden positions waving white flags. On the bridge itself, Lathbury’s men are under pressure from the north, leading to a precarious back-to-back defence. Lieutenant Peter Stainforth unit is acting as the brigade’s reserve on the south side and couldn’t do much at that point. The 1st Parachute Battalion is defending the northern side, while there is a lot of firing happening on the hills where John Frost is positioned.

An artillery officer with Frost eventually makes contact with the Royal Navy cruiser, H.M.S. Mauritius from Rear Admiral Cecil H.J. Harcourt’s 15th Cruiser Squadron. In addition to H.M.S. Mauritius, naval fire support during Operation Husky also comes from the cruisers H.M.S. Newfoundland and H.M.S. Arethusa.

The precise naval bombardment effectively breaks the German attack. Each time they try to regroup for another assault, they are met with devastating shellfire, forcing them to rely only on small-arms fire and sniping. The forward observation officer coordinating the naval fire is Captain Vere Hodge of the Light Regiment Royal Artillery.

By 09:00, the situation at Johnny 1 deteriorates due to limited weaponry, while an enemy patrol approaches the bridge from Catania. The Italian Major Vito Marcianò’s II Battaglione Speciale Arditi arrives with machineguns and mortars and Italian 29th Artillery Group (Battalion) lend direct support to the 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division. Advancing swiftly in their SPA-Viberti AS42 vehicles, they launch a counter-attack against British airborne troops. The patrol is driven back by mortar fire at 09:15, knocking out most of the Italian vehicles. Though the defenders at Johnny 1 suffer casualties, unable to dig effective defensive positions. Communication with the 8th Army is briefly established at 09:30, with the success signal “Marston One” relayed. However, wireless contact is soon lost.

Brigadier Lathbury, at the Primosole Bridge, has little information about what is happening behind him. The reduction in noise from the southern side makes him suspect that Frost and his men may have been overrun. Frost, however, has a good view of events unfolding below but cannot call for naval fire support for Lathbury’s men, as they are too close to enemy lines.

By 16:00 hours, the bridge and southern riverbanks come under concentrated shelling. With no sign of reinforcements from the 50th Infantry Division, Lathbury decides to withdraw what remains of the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions across the river and abandon the northern end of the bridge. Ammunition supplies dwindle, leaving captured enemy machine guns as a critical resource. Fires in surrounding fields complicate the defence further. Lieutenant Colonel Alistair Pearson with around 200 men, including a couple of platoons from the 3rd Parachute Battalion, establishes a defensive position around the approaches to the bridge. The Germans launch a series of attacks throughout the afternoon. The paratroopers aren’t in immediate danger of being overrun, but they are taking casualties and are running low on ammunition but. They do however think that they can’t hold out until nightfall.

Around 18:30 hours, Lieutenant Colonel Pearson receives an order to withdraw from Brigadier Lathbury, with which he disagrees, but ultimately does follow. Before leaving, he takes his provost sergeant “Panzer” Manser and his batman, Jock Clements, to reconnoitre the riverbank, as he has a gut feeling they might return. Around 450 metres along, they find a ford where they cross to return to the battalion lines.

Of the 295 British soldiers stationed at the bridge, 115 sustain injuries or are killed. The main dressing station of the 16th Parachute Field Ambulance cannot be relocated or evacuated, and it remains within the contested area.

An Italian officer arrives at the station, notifying the medical personnel that they are now prisoners of war. However, since they are treating casualties from both sides, they are permitted to continue their work. Throughout the day, treatment for the wounded persists, and by 22:00, the medical team has performed 21 surgical procedures while caring for 62 British and 29 German or Italian patients.

The retreat to the southern end of the Primosole Bridge temporarily creates a stronger position with concentrated firepower. However, German forces soon bring anti-tank guns close to the northern end, using them to destroy the pillboxes one by one.

As the guns fall silent and ammunition dwindles, the British Vickers machine guns are down to their last belts of bullets. A final, coordinated German assault comes down both sides of the river, using the smoke from burning reeds as cover. The British paratroopers are soon engaged in hand-to-hand combat. With no reinforcements in sight, Lathbury is forced to order another withdrawal. The paratroopers gradually fall back in the fading light, regrouping with the 2nd Parachute Battalion on the hills. Around 19:15 hours, with the situation becoming untenable, the remaining defenders at the bridge receive orders from Lathbury to withdraw southward in small groups. The Brigade Commander remains unaware that the 2nd Parachute Battalion still holds out at J.1. in the hills.

Major David Hunter is concerned that the Germans might cross the river and attack them from behind, asks Peter Stainforth to go with their Bren gunner to the right flank, where there is a Vickers machine gun. By this time, the 1st Parachute Battalion, almost out of ammunition, has withdrawn to the southern side of the bridge. The Germans, reinforced from Catania, attack with almost everything they have. With no other choice, Lathbury abandons the bridge. The brigade major, who crawls over to the paratroopers position, gives the impression that it is every man for himself. Some of the men, including Lieutenant Colonel Alistair Pearson, make it back to John Frost’s 2nd Parachute Battalion. However, Peter Stainforth has to take a lengthy detour west to avoid the enemy, at times hiding in the scrub, which ultimately takes him out of the fight.

Relief finally arrives at 19:45, as the first tanks of the 8th Army reach the 2nd Parachute Battalion’s position, reporting that infantry reinforcements are advancing quickly.

That night, Reverend Watkins leads a group of personnel to escape southwards from the Main Dressing Station. Those who remain, doctors, medics, and patients, brace for capture. By 22:00, the surgical teams have completed 21 operations, and the exhausted staff rests as much as they dare.

By 24:00, the long-awaited reinforcements arrive in force. Two battalions of the Durham Light Infantry secure the bridge area, taking over from the beleaguered airborne troops. The battle transitions to consolidation, ensuring the hard-fought gains are secured as the British forces prepare for the next phase of their campaign.

Morning at the Main Dressing Station brings an unexpected reprieve. Italian forces briefly take the Main Dressing Station but allow it to continue operations. Their occupation is short-lived as the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division’s forward troops advance through the area, securing the farm. By July 15th, 1943, the Main Dressing Station has treated 71 British and 38 enemy casualties. At 17:30, the site is cleared, and the remaining personnel regroup with the brigade. Captain Wright takes charge of evacuation, using the carts and a salvaged lorry to transport the wounded to safety.Over the next days, salvage parties recover parachutes and containers from the drop zones, though much of the medical equipment has been looted.

| 50th Infantry Division |

After the start of Operation Husky, on July 10th, 1943, the York and Lancaster Regiment, the lead element of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, is advancing slowly north along the road from Lentini, the 4th Armoured Brigade is also moving forward from Augusta. Both units encounter strong resistance from Group Schmalz, which consists primarily of the 115. Panzergrenadier Regiment, the 3. and 4. Fallschirmjäger Regiments, and three fortress battalions.

The day before, the leading battalions of the 69th Infantry Brigade from the 50th Infantry Division had reached Sortino but were exhausted. Just after dawn, Major General Sidney Kirkman arrives to meet Brigadier Edward Cooke-Collis, urging him not to rest but to push onwards towards Lentini. Kirkman insists to not let the enemy reform, stressing that there is little resistance ahead for now, but the next day could be much more difficult if the enemy has time to reorganise.

Early on July 13th, 1943, Major-General Sidney Kirkman, commander of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, is summoned to General Montgomery’s Eighth Army headquarters. During the meeting, Montgomery briefs Kirkman on the two missions involving British No. 3 Commando and the 1st Parachute Brigade, emphasising the necessity of capturing the bridges intact. Montgomery’s plan is for the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division to spearhead the Eighth Army’s advance and relieve the commandos and paratroopers. To assist with this objective, Montgomery places the 4th Armoured Brigade under Kirkman’s command.

Montgomery insists that the infantry division must relieve the paratroopers at the Primosole Bridge by the morning of July 14th, 1943. This involves the 69th Infantry Brigade advancing from Sortino to Lentini via Carlentini along a narrow single-track road. The subsequent objective is to reach Malati Bridge to relieve No. 3 Commando before continuing on to the Primosole Bridge. To the right of the 50th Infantry Division, the 5th Infantry Division advances up the coastal road, with both routes converging on Carlentini. Requiring them to advance approximately 40 kilometres within 24 hours.

However, the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, having landed on July 10th, 1943, has already been engaged in continuous combat for three days. With daily temperatures reaching as high as 38°C, many soldiers are suffering from physical exhaustion and heat-related fatigue.

The division’s predicament is further exacerbated by a significant miscalculation by Montgomery during the invasion’s planning. He had overestimated the resistance posed by German and Italian forces during the Allied landings. The British Eighth Army primarily consists of infantry, tanks, and heavy weaponry but lacks sufficient mechanical transport, meaning that any advance by the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division must be conducted on foot.

On the afternoon and well into the evening of July 13th, 1943, the 69th Infantry Brigade pushes forward. Both Generals Kirkman and Cooke-Collis remain close to the rear of their lead battalions, but it becomes evident that the strong defensive positions in front of Carlentini will require a full-scale assault to clear the path to Lentini that night. The advance is already behind schedule.

At XIII Corps HQ, Dempsey is concerned, but it is too late to delay the airborne operation again, and the Commandos are already en route by sea. The 69th Infantry Brigade has no option but to press on, as any further delay would allow the enemy time to destroy the two bridges.

Brigadier Cooke-Collis’s weary battalions continue the advance. A heavy artillery barrage rains down on Carlentini that night, coinciding with the departure of the 1st Airborne Brigade’s aircraft from Tunisia. At 08:30 the following morning, the 7th Battalion, Green Howards launch an assault on Monte Pancoli under intense bombardment from divisional artillery, heavy mortars, and Vickers machine guns. Eventually, the hill falls, and the advance into Carlentini resumes.

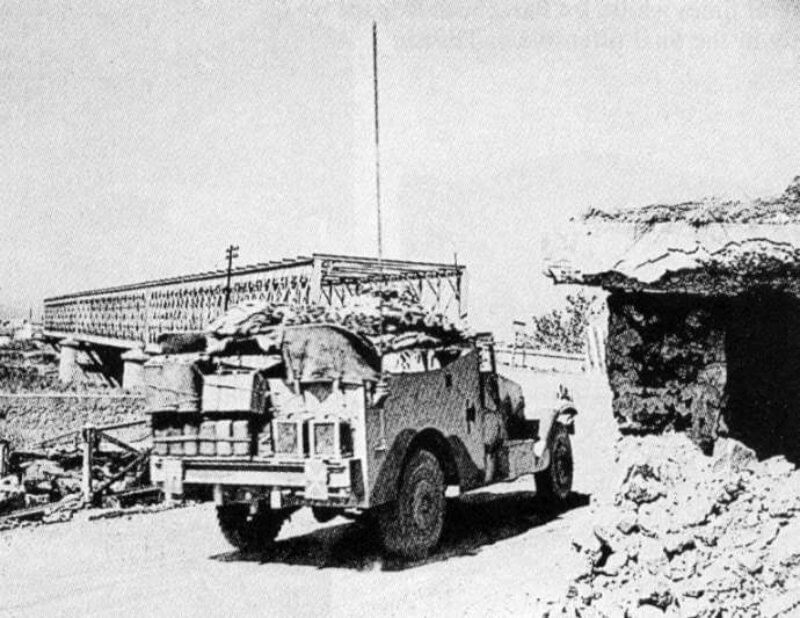

The Green Howards press onwards to Lentini, where the enemy lacks the advantage of high ground. British artillery and tanks clear the way, and with the fall of Lentini, the 5th Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment takes the lead towards the River Leonardo and the Malati Bridge. They are relieved to find the bridge still standing, and as daylight fades, they capture it after a brief firefight.

The advance is now taken up by the 151st Infantry Brigade, led by the 9th Durham Light Infantry alongside tanks from the 4th Armoured Brigade, heading towards the Primosole Bridge. The fighting at the bridge that day has been intense and desperate.

| Linking up with 1st Airborne Division |

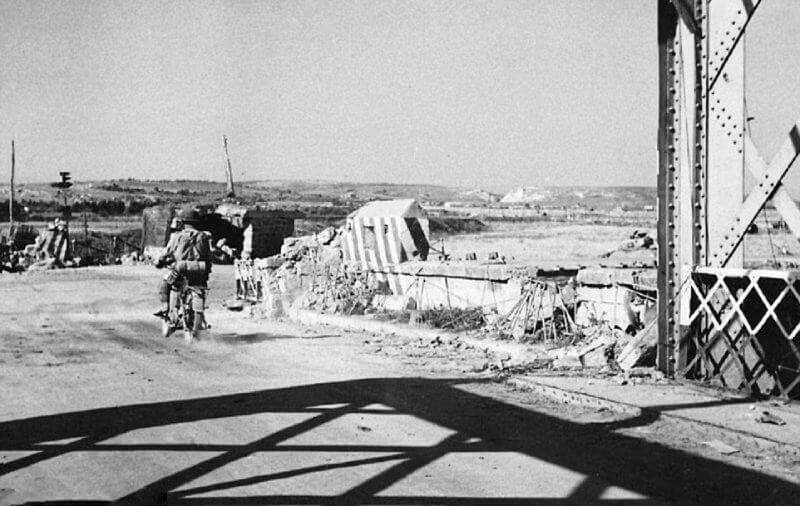

As twilight falls on July 14th, 1943, Bren gun carriers of the 9th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry, supported by tanks from the 4th Armoured Brigade, come into view below the positions held by the remnants of the 1st Parachute Brigade.

The arrival of these fresh forces prevents the Germans from advancing further or attempting to lay new demolition charges on the Primosole Bridge. The carriers are soon followed by the other two battalions of the Durham Light Infantry, led by Brigadier R.H. Senior, who establishes a substantial perimeter at the southern end of the bridge. Although his troops are too fatigued to launch a major attack that night, preparations begin for an assault across the river scheduled for 07:30 the next morning.

That night, A Company of the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry clears the southern end of the bridge, holding their positions in slit trenches under constant mortar and machine-gun fire at any sign of movement. At dawn, Royal Engineers move forward to clear mines.

On the opposite bank, elements of the German 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division are also fortifying their positions. These units include machine-gun and engineer battalions from General Richard Heidrich’s division, supported by a battery of paratrooper artillery, two 88 mm guns from a flak regiment being used in a ground role, and remnants of two Italian battalions. Further north near Catania, troops from Group Schmalz are regrouping, while the 4. Fallschirmjäger Regiment, largely intact, prepares to move south.

On the morning of July 15th, 1943, the 9th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry leads the British assault, wading across the river with support from field artillery and tank fire. The plan lacks finesse and demands considerable bravery, with the troops exposed as they cross the river on either side of the bridge. The supporting barrage lifts too soon, and the German paratroopers are well entrenched on the far side.

Some platoons manage to make it across under intense enemy fire. A few determined soldiers reach the German positions, engaging in hand-to-hand combat, but their numbers are insufficient to seize control, and they are forced to fall back. The London Times reports on the fight for Primosole Bridge, noting that the German troops “fought superbly. They were troops of the highest quality, experienced veterans of Crete and Russia: cool and skilled.”

As Alistair Pearson observes the 9th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry’s assault, he is unimpressed with the tactics being used by the British forces, despite recognising the skill of the German defenders.

He is called up to Durham’s Brigade Headquarters to discuss the next move. He listens in disbelief as the brigade commander suggests another attack that afternoon. Pearson tells them If they want to lose another battalion, they’re going the right way about it. There was a deathly silence as the two brigadiers gave me a long stare.”

Fortunately for Pearson, Brigadier Lathbury is also present, and Pearson avoids a reprimand. Instead, Lathbury manages to persuade the other senior officers to listen to his proposal: to take two companies from the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry across the river upstream from the bridge and position them on the enemy’s flank.

Shortly after 02:00, Lathbury leads his men across the Simeto River at a point where it is around 27 metres wide and 1.2 metres deep. Once across, they turn east and move towards the bridge. Upon launching their assault, a Very light flare signals the rest of the battalion and supporting units to storm across the bridge and establish a foothold.

The flanking force successfully pushes through the German positions, using surprise along with grenades and bayonets. Those German paratroopers who survive retreat into the vineyards and olive groves along the road to Catania. By dawn, the remaining two companies of the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry have crossed the bridge with tank support. They press on eagerly but soon come under heavy fire from all directions, quickly finding themselves in serious difficulty. The Durhams manage to advance only about 270 metres beyond the northern end of the Primosole Bridge before, as noted in the divisional history, “Lively fire was exchanged on both sides at ranges decreasing to 18 metres.”

The main obstacle is the presence of two 88 mm guns that have knocked out four Sherman tanks. With the tanks stalled by these well-positioned guns, the infantry is unable to advance without armoured support.

After the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry crosses the river and takes up defensive positions behind a low stone wall, I had my section dig in, and we all kept our heads down.

Brigadier Senior crosses the river to assess the situation firsthand but finds himself pinned down on the far side. General Kirkman also arrives, needing to communicate with his brigadier by radio due to the worsening circumstances. With the attack faltering and the tenuous lodgement at risk, Kirkman informs General Headquarters that the division will be unable to support an amphibious plan to capture Catania.

In response, Montgomery agrees to a 24-hour postponement of the amphibious landings. He then travels to the front alongside Dempsey to assess the situation personally. Upon arriving at the 50th Division HQ, Montgomery is informed that another attempt to secure the front north of the Simeto River will be made that night.

At 01:00 on July 17th, 1943, the 6th Battalion and 9th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry cross the river at the “Pearson” ford, to the left of the Primosole Bridge. This time, the attack involves two entire battalions rather than just two companies. The Durhams reach the Catania road and successfully overpower the defenders—comprising German paratroopers and detachments from the Hermann Göring Division—before digging in just in time to repel a counterattack by German paratroopers and tanks.

More British tanks manage to cross the river, expanding the bridgehead and prompting isolated groups of enemy troops to surrender. The cost of the assault is high; the two attacking Durham Light Infantry battalions suffer the loss of 220 men.

| Aftermath |

With new intelligence in hand, Montgomery reassesses the situation. Between the River Simeto and the city of Catania, in a relatively narrow coastal plain, a significant number of determined German troops are positioned, with reinforcements, such as the 15. Panzergrenadier-Regiment from the 29. Panzergrenadier-Division, arriving as recently as July 16th, 1943.

It is now evident that the 50th Infantry Division will face significant challenges in breaking out from the Simeto bridgehead to link up with seaborne landings further north. As a result, the planned amphibious operation is abandoned, and a new approach must be devised to reach Catania.

Montgomery’s positive demeanour is beneficial for morale, but his race to capture Catania quickly has ended in failure. He gambled on a swift victory, but the campaign ahead will now involve prolonged and intense fighting.

Of the 292 officers and soldiers from the 1st Parachute Brigade who make it to the Primosole Bridge, twenty-seven are killed and seventy-eight are wounded, with many others reported missing. Approximately four hundred additional paratroopers who do not reach the bridge are either killed, injured, or captured during the landings.

| Multimedia |