| Page Created |

| May 30th, 2025 |

| Last Updated |

| June 2nd, 2025 |

| The United States |

|

| Related Pages |

| Office of Strategic Services |

| History |

|

The Javaman project, originally designated Campbell, is developed by the Office of Strategic Services during the Second World War to create remote-controlled explosive motorboats. These vessels are designed to be guided from B-17 bombers and deployed against enemy shipping and harbour installations that are inaccessible to conventional methods of attack.

The project’s mission is the sabotage of enemy targets inaccessible to other methods of attack. These targets, protected by inner and outer harbour defences, are best approachable by operational ruse and deception.” The strategic aim is to infiltrate fortified maritime areas using camouflaged, remotely piloted vessels carrying significant explosive payloads.

The intention is to use boats designed as a lightweight, high-powered motor launches, with a low silhouette to avoid detection. Capable of speeds ranging from 8 to 72 kilometres per hour, they are equipped with a television camera to allow remote navigation from an accompanying aircraft or surface vessel. To provide a stable image, the camera is mounted on a platform stabilised by a tank gun gyroscope adapted from standard U.S. Army Ordnance.

| Remote Control System |

The remote control station may be positioned up to 32 kilometres from the target area. This control point can be located aboard an aircraft, a mother ship, a submarine, a second small vessel within the harbour, or at a concealed shore position operated by Office of Strategic Services agents.

The control equipment at this location consists of a compact television receiver and a radio control system comprising several portable units with a combined weight of approximately 90 kilograms. This lightweight design allows for easy transport and rapid deployment across various platforms.

The heart of the system is the AN/ARW-8X radio control apparatus, which is structured into two groups of channels, each group managing five separate functions. The primary group governs navigation and propulsion and includes the following controls:

- Ignition switch

- Forward, to accelerate the engine

- Reverse, to reduce speed or decelerate

- Right rudder, to steer starboard

- Left rudder, to steer port

The secondary group manages auxiliary functions critical to mission execution. These include:

- Detonation, to trigger the scuttling charge or initiate explosive detonation

- Sonics, to activate the audio playback and simulated exhaust smoke system

- Spare control 1

- Spare control 2

- Spare control 3

These final three are reserved for mission-specific needs, allowing for adaptable configuration depending on operational requirements.

One trained operator is sufficient to manage the system. By selecting the appropriate radio frequency channel, the operator sends targeted impulses to the missile, activating the desired commands in real time. This precise control ensures the vessel responds accurately to steering, speed adjustments, and activation of auxiliary systems, even from considerable distances. After technical improvements, the system achieves reliable operation at distances of up to 140 kilometres from B-17 aircraft flying at an altitude of 6,100 metres.

Regardless of the size or type of the missile-craft, the onboard remote control equipment remains standardised. Each vessel is fitted with an antenna designed to receive radio impulses transmitted from the control station. These signals are processed by the onboard radio receiver, the AN/VRW-1 unit.

Upon receiving the signal, the AN/VRW-1 activates a series of servo mechanisms. These servo units in turn govern key operational functions of the craft, including ignition, throttle, rudder control, and any additional systems specified for the mission. This configuration ensures consistent responsiveness across all Campbell/Javaman variants, whether small or large.

| Multimedia |

8X.

| Television System |

In circumstances where the missile remains within visual range of the operator, such as operations conducted from a nearby vessel, shoreline, or elevated observation point, the use of television guidance may be unnecessary. In such cases, the radio control system alone is sufficient to direct the missile accurately to its target.

Within the range of the television equipment the the vessel can be guided beyond the the eyesight of the control operator. In the viewing scope of the standard television receiver, the SCR-550, the operator sees the target and any obstructions in the course ahead just as he is at the wheel of the vessel. Reception is kept at the same level by a gyroscopic antenna on the aircraft that is synchronised with at all time with the AS-27/ARN-5 Wishbone Antenna on the vessel.

The visual feed at the remote control station is provided by a standard Navy ATK television camera installed in the bow of the missile-craft. This forward-facing camera is designed to focus to infinity and captures all objects within its line of sight, short of the horizon. It offers a horizontal field of view of 22 degrees, allowing the operator to see a precise, forward-facing image of the craft’s surroundings.

Integrated into the camera system is a gyroscopic compass, which remains visible on the transmitted image at all times. This feature enables the operator to monitor the vessel’s heading continuously and make accurate course corrections as required.

To ensure functionality under operational conditions, the camera, along with its associated conversion unit, is housed within a sealed casing that protects it from vibration, moisture, and external noise. The camera’s feed is transmitted in real time to the remote control point, providing the operator with a clear and stable image for navigation and targeting.

| Multimedia |

| Detonation System |

Each missile-craft carries two distinct sets of explosive charges, one designed to scuttle the vessel, the other to destroy the designated target. The primary scuttling charge consists of Primacord, a high-velocity detonating cord wound throughout the interior of the craft, running along the hull bottom and bulkheads. In locations where additional force is necessary, plastic explosives are incorporated to enhance destructive effect.

In the event that the missile fails to make direct contact with the target, a network of contact firing switches mounted at regular intervals around the gunwales will automatically detonate the Primacord. Normally, the scuttling charge is triggered by a mechanical pin-up device installed in the bow. Upon striking the target, this device drives case-hardened steel pins into the hull of the ship. Simultaneously, it activates the scuttling charge, which blows away the bow and stern sections and severs the lower hull, causing the missile to sink rapidly.

As a safeguard against premature detonation of the main charge, each section of high explosive is housed within separate, reinforced compartments. These protective enclosures prevent the shock of the scuttling charge from inadvertently setting off the primary explosive payload.

Various types of munitions may be used for the main charge, depending on theatre availability and mission objectives. These include depth charges, block TNT, Torpex, Tetratol, Composition C-2, aerial bombs, or other high-explosive devices. These charges are typically fitted with hydrostatic fuses, which can be set to detonate at predetermined depths.

When the pin-up device engages a target, it not only anchors the missile via steel pins but also initiates the scuttling sequence. A steel cable running between the pin-up device and the missile’s internal frame holds the explosive-laden hull close against the target. This ensures the main charge, which detonates at a preset depth, explodes in direct proximity, maximising destructive effect.

| Multimedia |

| Operational Disguise |

Successfully penetrating enemy harbour defences requires careful deception, informed by intelligence gathered by Office of Strategic Services operatives familiar with local maritime customs. These agents provide detailed observations regarding the habits, appearance, and patterns of native craft permitted to move freely within enemy-controlled waters.

Such deception is not limited to superficial resemblance. It demands precise knowledge of harbour recognition signals, net and boom barriers, underwater acoustic detection systems, minefield layouts, patrol schedules, local maritime regulations, and other defensive measures. In almost all cases, a custom-built disguise tailored to the target harbour’s specific conditions is essential.

Disguise planning begins with intelligence reports, photographs, and operational requirements, particularly the size of the missile-craft needed to carry out the assigned mission. If contact can be established with sympathetic locals, it may be possible to replicate a known vessel and substitute it with the missile-craft. This permits the boat to blend in seamlessly with the existing harbour traffic.

The disguise process typically involves constructing a false plywood hull over a lightweight frame secured to the missile. This false hull recreates the length, beam, and distinctive lines of the original native vessel. Weathering, paintwork, identification markings, and deck accessories are carefully replicated to enhance realism.

To suppress the distinctive noise of the high-powered engine, the engine compartment is thoroughly soundproofed. A loudspeaker system plays a continuous recording of a native engine, using a 16 mm film loop on a concealed projector. Simulated exhaust is produced by igniting raw cotton linters, the smoke from which is fed into the exhaust pipe and released in synchrony with the audio track.

Beyond these technical features, visual authenticity is further enhanced by placing a life-sized dummy of a native helmsman at the tiller. Articulated by a universal joint, the figure sways naturally with the motion of the boat and appears to steer it, contributing to the illusion of a manned vessel.

| Multimedia |

| The Campbell Javaman Programme |

The Campbell programme is initiated by the Office of Strategic Services in March 1944 and placed under the command of Lieutenant Commander John Shaheen of the United States Navy Reserve. The first round of testing takes place on april 5th, 1944 and April 6th, 1944 at the United States Army Mine Command Headquarters in Little Creek, Virginia.

Three vessel types are selected for the programme:

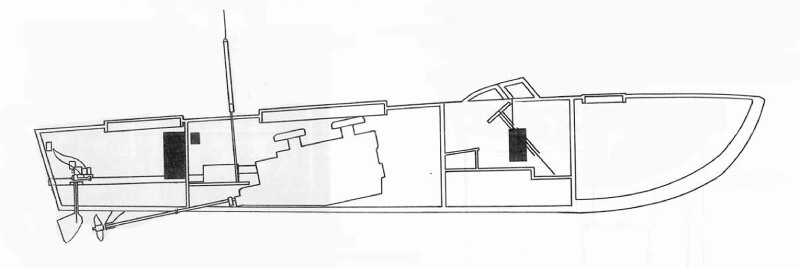

- The A-2 Hacker Craft measures 10.6 metres and carries up to 2,250 kilograms of Torpex explosives. It is powered by a 410-kilowatt (550-horsepower) Kermath petrol engine.

- The A-3 Hacker Craft, measuring 11.3 metres, is capable of carrying 4,500 kilograms of Torpex explosives and uses the same 410-kilowatt (550-horsepower) Kermath petrol engine.

- An 25.9-metres Army rescue vessel is adapted to serve as a heavy explosive boat, carrying up to 22,500 kilograms of Torpex. It is powered by two Packard engines, each generating 930 kilowatts (1,250 horsepower).

On August 11th, 1944, a live-fire test is conducted at 07:00 in the Gulf of Mexico off Pensacola. In this early test, two men take the motorboat to a rendezvous point with a B-17 bomber. Once in position, control of the boat passes entirely to the operator onboard the aircraft, who will guide it remotely from miles away. The missile is a 10.4-metre A-2 Hacker craft with a low profile, powered by a 410-kilowatt engine. It reaches speeds of 56 kilometres per hour, has a range of 354 kilometres, and can carry 2,270 kilograms of explosives. The range can be increased with additional fuel tanks.

Designed as a one-way weapon, the boat carries no crew. Instead, it is fitted with a radio receiver and a television transmitter. The forward-facing camera, mounted on the bow in a stabilised housing, provides a live video feed to the operator, who monitors the vessel’s progress in real time. In this case, the B-17 serves as the control platform, equipped with a television receiver and radio transmitter. However, the operator could just as easily be based on a ship, submarine, coastal craft, or a concealed shore position.

Once the plane establishes visual link with the missile, the operator takes over entirely. From that point on, the boat is steered by remote control. Thanks to improved transmission systems, television-guided control is reliable at ranges up to 140 kilometres, even from an aircraft cruising at 6,100 metres. The operator uses the video feed to navigate, adjusting course and speed to avoid obstacles such as patrol boats, buoys, and defensive nets.

Remote control also allows the operator to start or stop the engine, switch on simulated sound effects, emit smoke, and trigger the explosive charges.

Following these promising results, the Office of Strategic Services begins full-scale preparations in August 1944 for a live trial. The chosen target is the SS San Pablo, a 5,000-tonne freighter anchored in the Gulf of Mexico off Pensacola. The boat, designated K-354, is to be disguised and launched under realistic combat conditions.

On August 11th, 1944 at 07:00, the Office of Strategic Services conducts a full-scale test of the Campbell system under operational conditions in the Gulf of Mexico off Pensacola. The objective is to assess remote control handling, seaworthiness, realism of the disguise, and the missile’s ability to destroy a naval target.

For this trial, an A-2 Hacker craft is converted into a replica of a Danish fishing vessel operating out of Copenhagen. Intelligence reports from Office of Strategic Services agents in Denmark provide detailed specifications of native fishing boats. One specific vessel, designated K354 and equipped with a single mast and a one-cylinder diesel engine, is selected as the model.

The missile-craft is transformed into a credible duplicate of K354. Its mission: to deliver a payload of explosives to the 5,000-tonne, 91-metre freighter SS San Pablo. The vessel is launched, navigated by remote control, and brought into position while maintaining the deception. The trial aims to demonstrate that a remotely guided explosive boat, operating under a well-designed disguise, can successfully infiltrate defended waters and destroy a major enemy target without being detected until it is too late.

To ensure the disguise holds up against hydrophone detection, the Office of Strategic Services conducts sound trials at Fisher Island. These reveal that at speeds below 800 revolutions per minute, the motorboat is acoustically indistinguishable from genuine fishing craft. At higher speeds, used only during the final strike, the difference becomes detectable, but by then, the deception is no longer necessary.

The disguised missile, now complete, is loaded with 14 depth charges containing torpex. These are fixed inside the hull, with a total explosive weight of 2,250 kilograms. At the bow, a “pin-up” device is fitted: a double-barrelled mechanism mounted on a retractable boom that, upon impact, drives steel pins into the target’s hull. Attached cables then secure the payload tightly against the ship. Even if the pin-up mechanism fails, contact fuses along the boat’s edge will still trigger the scuttling charge.

The television and control systems are installed aboard K-354. A stabilised transmission system, power source, and camera are housed inside a soundproof casing to ensure clarity. Two-way radio control is tested, and batteries fully charged. The disguise now complete, the boat is ready for deployment.

The B-17 control aircraft is fitted with a television monitor and radio controls. Once airborne, it establishes contact with the boat, which has been piloted out and left unmanned by its crew. The operator aboard the aircraft takes control.

Guided by the television feed, complete with compass overlay, the operator steers the boat toward the SS San Pablo. The control system allows full steering, speed control, and the ability to initiate smoke and sound effects. A telemeter records speed and transmits it back to the operator, allowing precise handling.

From eight kilometres out, the SS San Pablo appears on the television screen. The missile closes in. At one mile, it is directly ahead. From the water, the low-slung boat is barely visible. On screen, the operator adjusts for final approach. The missile strikes. The scuttling charge detonates, pulling the depth charges close to the hull. The explosion follows 25 seconds later.

The freighter breaks apart. Within one minute and 40 seconds, the SS San Pablo sinks to the seabed, 26 metres below. Divers later inspect the wreck. They report a gaping hole beneath the waterline, approximately 18 by 12 metres. The keel is fractured, rivets torn, and daylight visible through the wrecked hull. The missile is completely destroyed, leaving no recoverable evidence for enemy analysis. The shockwave is estimated to have extended 150 metres.

If a missile is discovered during final approach, it is likely too late for the target to respond. Particularly with larger boats like the A-3 or Air Rescue Boat, the closing speed and proximity make interception impossible. Aerial footage shows the strike in slow motion. Shockwaves ripple outwards, fore and aft charges detonate, and the ship breaks apart.

The Office of Strategic Services concludes that Campbell Javaman vessels are ready for operational use. Each mission would require individual planning, appropriate disguises, and careful deployment.

By March 1945, the project has expanded significantly, with 152 personnel stationed at its secret operational base in Saint Petersburg, Florida. Despite the system’s success in controlled tests, objections raised by the United States Navy regarding its deployment in the Pacific, coupled with the impending end of the war, result in the boats never being used in combat.

| Multimedia |

sound and smoke

was attached to the

underside of the after deck side.

| Documents |