| Page Created |

| July 7th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| July 16th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Included Operations |

| Operation Titanic Operation Nelson Operation Samwest Operation Grog/Grog Operation Dingson Operation Bulbasket Operation Cooney Operation Houndsworth Operation Lost Operation Swan II Operation Gain Operation Defoe Operation Derry Operation Hardy Operation Wallace Operation Gaff Operation Dunhill Operation Loyton |

| Operational Areas |

| Special Air Service 6th Airborne Division Band Beach Sword Beach Gold Beach Juno Beach Omaha Beach Utah Beach 82nd Airborne Division 101st Airborne Division |

| Operations within Operation Overlord |

| Operation Gambit Operation Neptune Operation Perch Operation Epsom Operation Charnwood Operation Atlantic Operation Goodwood Operation Bluecoat Operation Totalize |

| June 6th, 1944 |

| Special Air Service |

| Objectives |

- Drop Parachutist-Dummies, noisemakers and small numbers of special forces troops in order to draw the Germans away from the real D-Day Drop Zones.

| Operational Area |

North of the River Seine (Titanic I), West of Utah Beach (Titanic IV)

| Unit Force |

- Six Special Air Service men from A and B Squadrons, 1 Special Air Service, Special Air Service Brigade

| Opposing Forces |

- 91 Luftlande-Division

- Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6

- Stellungs-Werfer-Regiment 101

| Operation |

Operation Titanic IV marks the first deployment of Special Air Service troops in north-west Europe, involving six men and one aircraft during D-Day on June 6th, 1944. Although often dismissed as a minor part of a larger deception ploy, it plays a crucial role in the success of the Normandy invasion by being part of a comprehensive strategy that includes Operations Fortitude North and South.

Hitler and the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) believe that a failed Allied invasion would significantly delay another attempt, allowing German divisions to be redirected to the Eastern Front. They anticipate secondary invasions in Norway or the Balkans, maintaining eleven divisions in Norway and twenty in the Balkans, with forty-one in France. Hitler’s accurate assessment, supported by Admiral Theodor Krancke, is based on three key observations: Luftwaffe reconnaissance, including high-altitude jet-propelled Arado Ar234 flights, reveals no build-up of landing craft opposite Pas de Calais; Allied bombers target Kriegsmarine shore batteries between Boulogne and the Cotentin peninsula; and railways to Pas de Calais are heavily bombed, unlike those leading to Cherbourg and Brittany.

Hitler anticipates Allied airborne assaults on Cotentin and Brittany, recalling high casualties in Crete and Sicily. By May, three new units are deployed to Cotentin: the 91 Luftlande-Division, Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6, and Stellungs-Werfer-Regiment 101. These units are well-equipped and trained. The 91 Luftlande-Division includes two regiments (six battalions) of infantry, artillery units, and a mobile infantry battalion, Fusilier-Bataillon 91, mounted on bicycles for anti-paratroop operations. The Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6 is notably strong, with fifteen companies, including heavy weapons. They are highly trained paratroops, although without parachutes in France, bringing confidence from their training and superior firepower. The Stellungswerfer Regiment 101 has three battalions of heavy rocket launchers, including the feared 15cm Nebelwerfer and 24cm Heulen Kuh. This regiment is well-trained in anti-airborne tactics and can move between the east and west coasts of Cotentin as needed.

| Operation Titanic |

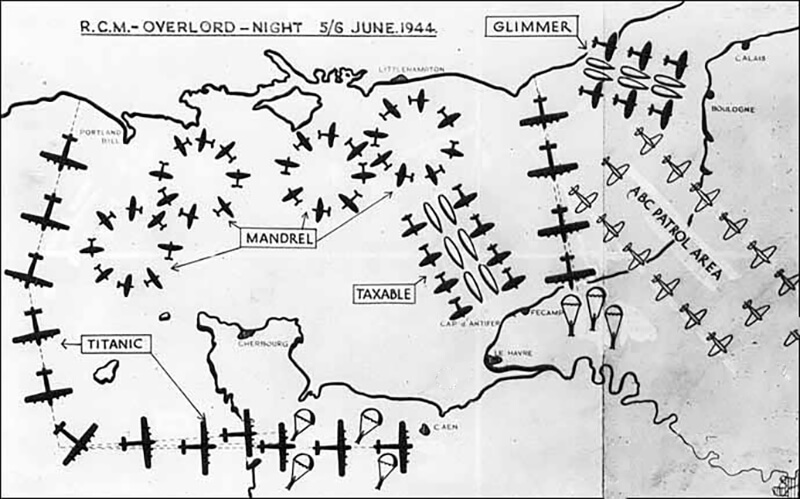

Operation Titanic, part of the broader Operation Fortitude South deception plan, aims to simulate paratroop landings behind German coastal defences, diverting attention from real landings.

- Titanic I simulates a division landing north of the River Seine to draw enemy reserves, especially the 12 SS-Panzer-Division Hitler Jugend, north of the river.

- Titanic II simulates landings in eastern Normandy to hold enemy forces west of the Seine.

- Titanic III coincides with British 6th Airborne Division landings to divert forces south of Caen.

- Titanic IV coincides with US landings west of Utah Beach to divert forces from the coastal area. It operates in conjunction with Operation Bigdrum, involving deception gear on launches and radio countermeasures to simulate a massive stream of aircraft approaching the Cotentin peninsula.

Due to a lack of transport aircraft and Special Air Service troops, only Titanic I and Titanic IV proceeds. Titanic I proceeds without Special Air Service operators but includes the Window and Parachutists-Dummies, nicknamed, Rupert. The Titanic IV mission involves six Special Air Service men from A and B Squadrons: Lieutenants Frederick James Poole and Norman Harry Fowles, and Troopers Jack Dawson, Saunders, Hurst, and Merryweather. They face considerable opposition, with German forces in the Cotentin region well-prepared for airborne assaults.

| May 19th, 1944 |

The fate of Operation Titanic is uncertain. Special Air Service Brigade Operation Instruction No. 11 states that “Pending results of representations to 21st Army Group by Corps Commander it must be assumed that SAS troops’ commitments in cover plan as described to you verbally will stand.”

These commitments include Titanic I with three parties of three men from 2 Special Air Service to drop in the Yerville area, eastern Normandy, approximately 160 kilometres east of the D-Day beaches, and Titanic IV: two parties of three men from 1 Special Air Service to parachute into Marigny, about 48 kilometres south of Utah Beach. Their mission is to divert German troops stationed near the American 101st Airborne Division’s landing zone.

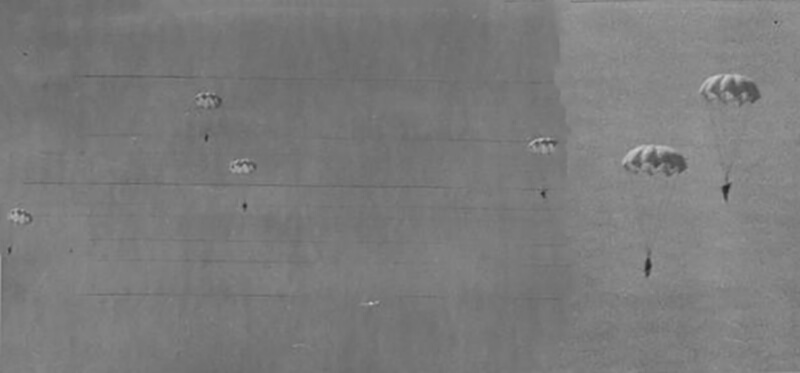

Titanic I’s parties are to parachute onto their Drop Zone (DZ) four hours and forty minutes before H-Hour, and Titanic IV’s at five hours before H-Hour. One minute after the men jump, several hundred dummy parachutists, dubbed “Ruperts,” will be dropped onto a nearby Drop Zone. These dummies, made of sandbags and equipped with simulators, are designed to represent rifle and light machine gun fire and will explode upon landing. Pintail bombs containing Very light cartridges will also be dropped to create the illusion of a major airborne assault.

| May 24th, 1944 |

The corps commander receives the results: Titanic I is cancelled, but Titanic IV will proceed as planned. The selected officers for Titanic IV are Lieutenants Norman “Puddle” Poole and Frederick “Chick” Fowles. Both are recent recruits to the regiment. They volunteer for Titanic IV along with Troopers W. Hurst, Robert “Chippy” Saunders, J. Dawson, and Anthony Merryweather.

| May 27th, 1944 |

The bulk of the Special Air Service Brigade moves from Ayrshire to holding camps near Royal Air Force Fairford in the Cotswolds. The troops arrive late that day and those detailed for operations between D-Day and D+14 move from Cirencester station to a holding area, a transit camp near Royal Air Force Fairford. The camp holds a large number of men as the teams for Operations Titanic IV, Bulbasket, Houndsworth, Dingson, Samwest, and Gain are stationed there, along with the brigade command and administrative staff; nearly 500 men.

The two teams for Titanic IV are selected by the commanders of A and B Squadrons. The six men are not told of their mission until after they arrive at Royal Air Force Fairford.

| May 29th, 1944 |

There is some confusion in the final week of May about the exact composition of Titanic IV. A memo states that “Titanic IV will NOT take place as planned. Revised plan now under consideration.“

The men of Titanic are finally briefed about their mission by Paddy Mayne and the brigade Intelligence Officer, Captain Michael Foot. Lieutenants Fowles and Poole, appear to be horrified by the mission’s suicidal nature but resolve to continue after encouragement from their comrades.

| June 1st, 1944 |

The final operation memo specifies two parties of three all ranks from 1 SAS Regiment. The six soldiers will now be dropped by a Halifax bomber instead of a Stirling or Albemarle.

The memo includes a paragraph on “Withdrawal,” outlining options for the two parties to hide after completing their task and either infiltrate back through enemy lines, withdraw to Special Air Service base areas, or be recovered by sea later. Poole and Fowles, alongside Lieutenant Ian Stewart from Operation Houndsworth, spend their days studying maps and aerial photographs and learning methods to avoid being tracked by enemy forces.

The intelligence indicates no static German troops in the area, except at Périers, the headquarters of 243 Infantry Division. Mobile units include the 352 Infantry Division in Amigny, tasked with counter-attacks against western Normandy beaches, and 30 Mobile Brigade, spread around Saint-Lô and Coutances.

| June 3rd, 1944 |

Lieutenants Poole and Fowles are escorted by Captain Mike Sadler to Hassells Hall in Bedfordshire. Known as ‘Hush-Hush House,’ it is the final stop for agents before their missions into Occupied Europe. Captain Sadler, an experienced Special Air Service officer, is impressed by Lieutenant Poole’s piano skills, which help soothe nerves as they await the operation.

| June 5th, 1944 |

Hassell Hall is busy as Paddy Mayne addresses his men one final time. A memo from Lieutenant General Frederick Browning states that Paddy Mayne will attend the briefing of Flight Lieutenant Robert Johnson, the pilot, at RAF Tempsford at 18:00 hours. The briefing outlines contingency plans for dropping the parties if the primary Drop Zone faces heavy fire.

The regiment, although relatively egalitarian for its era, still faces uncertainties about whether troopers can socialise and dine with officers, likely keeping them apart. The hall is filled with Special Operations Executive agents, conducting officers, and staff officers from both Special Operations Executive and Special Air Service.

The Special Air Service officers spend much of their day solving jigsaw puzzles, watching films, and chatting with two young women who help with the puzzles. The Special Air Service troops are unaware that one of these women is Violette Szabo, an Special Operations Executive agent about to embark on her second mission to France.

Nearby, members of Jedburgh Team Hugh prepare for their flight with the Bulbasket reconnaissance team on Mission Politician. The team consists of Capitaine L.L. Helgouach, a French weapons and demolitions instructor, Lieutenant R. Meyer, a wireless operator, and Captain William Crawshay, 8th Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers, the team leader.

As evening approaches, the Titanic and Bulbasket teams gather their equipment, including Bergen rucksacks, radios, and weapons. They travel to the airfield to collect their parachutes and pigeons. Tempsford airfield is active with aircraft preparing for departure.

The containers accompanying the soldiers contain Parachutist-Dummies, pintail lamps, and rifle fire simulators, along with Window to jam enemy radar. The soldiers’ equipment includes essentials such as weapons, rations, radios, and personal items.

Among the first to take off are the Halifax aircraft of No. 138 Squadron, embarking on the Titanic missions. For Titanic I, seven Halifax aircraft from No. 138 Squadron and four Stirlings from No. 149 Squadron, flying out of Royal Air Force Methwold in Suffolk, are tasked with delivering Window and other materials. Additionally, one Halifax is assigned to Titanic IV, with further Stirlings dropping Window and the Parachutist-Dummies for the same mission.

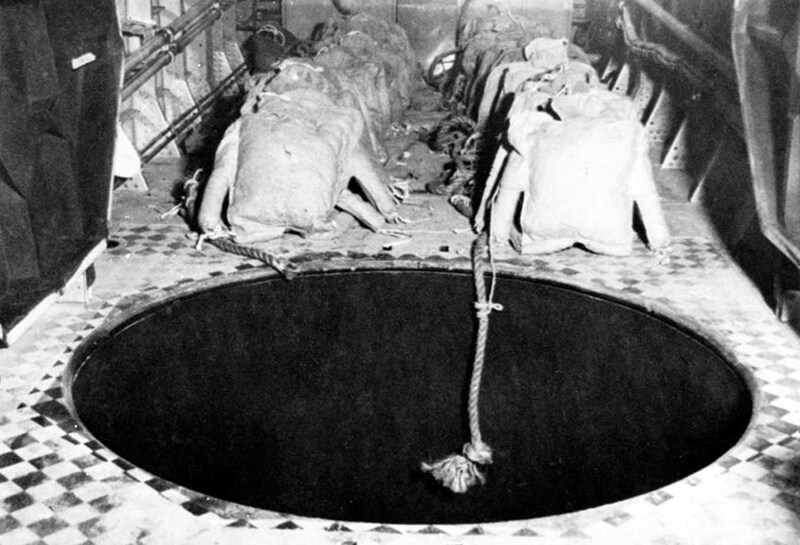

Titanic I proceeds despite the challenging weather, which includes a low cloud base of 300 metres over the Drop Zone (DZ) areas, positioned approximately 75 metres above sea level. The operation involves seven Halifax BII aircraft from No. 138 Squadron. Four of these aircraft drop the Parachutist-Dummies. and packages through Joe-holes, while the remaining three, along with the Stirlings, drop Window. The operation appears to go according to plan, demonstrating the detailed preparation and coordination typical of such wartime missions. The eighth Halifax, NF-M, flown by Flight Lieutenant Johnson, carries the Titanic IV teams and their containers. It takes off as scheduled.

| June 6th, 1944 |

NF-M, is logged back at Tempsford at 03:00; the log entry simply states “Dropped Party.” The Royal Air Force has played its part, delivering the Special Air Service teams to the Drop Zone. However, the jump is not as straightforward as the log suggests.

In reality the Titanic IV mission quickly encounters difficulties.

The Halifax makes an accurate landfall near Avranches and begins its approach to the DZ. When the aircraft is estimated to be eight minutes away, the navigator switches on the dispatcher’s red standby light. Due to a malfunction, the light changes to green, indicating “Go,” almost immediately. This sudden change leaves no time to think; the dispatcher and paratroops, fixated on the light, react instinctively. The dispatcher yells ‘Go,’ and they jump – quickly. The malfunction results in the two teams being dropped about seven minutes ahead of schedule, at 00:20 hours. The unexpected light change momentarily confuses them, and a slight pause before No. 2 in the stick follows Lieutenant Fowles through the Joe-hole causes a further scattering. To complicate matters, the last man, Lieutenant Poole, trips over his leg-bag and knocks himself out. He must have been last as no one sees him stumble. The majority of the team lands approximately two kilometers north-west of the intended Drop Zone.

There is no report of dropping containers or the sight of Very lights or the sound of simulated rifle fire. When the parties rally, they discover that Lieutenants Poole and Fowles are missing. The four remaining troopers bury their parachutes and, with good visibility, conduct an extensive search for the containers. They find none and see no sign of the two missing officers. The four troopers are on their own.

At 03:00 hours, with dawn approaching, they decide to follow their instructions from Fairford. They spread out around the DZ, plant their Lewes bombs, and withdraw. The bombs explode but fail to attract immediate attention. The group moves north away from the landing area and hides in a thick hedge. They remain there all day, seeing no movement apart from a patrol of German bicycle troops on the St Lô-Carentan road. Throughout D-Day, they observe limited German patrol activity.

In the evening, around 20:00 hours, a member of the local Resistance, Monsieur Edouard le Duc, contacts them. How he finds them is unknown, possibly through a farmer or farm worker nearby. Monsieur le Duc communicates – the language is not specified – that he will lead them away later that night. He departs but returns after about three hours, guiding them westward for about three kilometers to the ruins of an old abbey, possibly the Maison de Marais, near the present-day D 900 between St Lô and Périers. Monsieur le Duc helps the troopers find a hiding place and then leaves. The group remains hidden throughout D-Day, undisturbed and content to be safe, faintly hearing the sounds of battle from the east.

| June 7th, 1944 |

The next morning, Monsieur le Duc returns with Lieutenant Poole, who has been unconscious for forty-five minutes after his rough landing. Poole has buried his parachute and sent a message via carrier pigeon to Special Air Service Headquarters. With Poole reunited with the group, they spend three days hidden in the abbey, conducting local patrols and being supplied with food by the Resistance.

| June 10th, 1944 |

Monsieur le Duc brings Lieutenant Fowles to the abbey. Fowles has landed close to the Drop Zone but has been separated from the group. He spends several days hiding and conducting minor sabotage, including cutting telephone wires and sniping at Germans. Despite their isolated actions, Fowles and the troopers decide to remain at the abbey until they can be overtaken by the advancing Allied forces, initially expected by June 18th, 1944. They are supplied by the local Resistance.

| June 25th, 1944 |

Monsieur le Duc leads three US paratroopers, escaped prisoners from the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, to the Special Air Service hiding place. The group’s food supply is critically low, forcing them to forage for vegetables.

| June 28th, 1944 |

German forces, including Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 6, move into nearby Remilly-sur-Lozon, the Special Air Service team is warned by Monsieur le Duc to relocate. They move south and hide in an old brushwood cabin.

| July 2nd, 1944 |

The group decides to move north, hoping to reach Allied lines. They make slow progress, crossing open countryside and the River Taute.

| July 9th, 1944 |

During the night, they reach the village of Raids and hide near a German position.

| July 10th, 1944 |

A German patrol discovers them, leading to a skirmish where Hurst and Merryweather are seriously wounded by grenades. The uninjured members, Poole, Dawson, and Saunders, carry the wounded to a farm, where they are captured by German Fallschirmjager. After their capture, they are taken to a German headquarters. After brief interrogation, they receive medical treatment at a makeshift surgical station and are eventually moved to a temporary military hospital in Rennes. Following the liberation of Rennes by U.S. forces in August, the captured troops receive proper medical care and are freed.

| Aftermath |

Poole, Fowles, Dawson, and Saunders spend the rest of the war in a Prisoner of War camp. Fowles and Poole receive the Military Cross for their leadership, and Merryweather is awarded the Military Medal for his bravery.

| Multimedia |