| Page Created |

| June 1st, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| June 15th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Included Operations |

| Coup de Main Operation Tonga Operation Mallard Operation Rob Roy |

| Operational Areas |

| Special Air Service 6th Airborne Division Band Beach Sword Beach Gold Beach Juno Beach Omaha Beach Utah Beach 82nd Airborne Division 101st Airborne Division |

| Operations within Operation Overlord |

| Operation Gambit Operation Neptune Operation Perch Operation Epsom Operation Charnwood Operation Atlantic Operation Goodwood Operation Bluecoat Operation Totalize |

| June 6th, 1944 |

| Coup de Main |

| Objectives |

- Capture Bénouville bridge over the Caen Canal

- Capture the Ranville bridge over the Orne River

- Hold the bridges until relieved

| Operational Area |

- Bénouville and Ranville area, Normandy, France

| Unit Force |

| Opposing Forces |

- 736. Grenadier Regiment, 716. Division

- 21. Panzer Division

- 12. SS Panzer Division “Hitlerjugend”

| Operation |

During the planning stages of the Normandy invasion, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, the commander of the Allied 21st Army Group, decides to secure the left flank of the Normandy beachhead by landing the British 6th Airborne Division on the west side of the Orne River. One of the primary tasks of the division is to secure and maintain a viable avenue of approach towards the city of Caen for the armoured forces landing on Sword and Juno beaches. To accomplish this and to prevent the Germans from flanking the landings, Major General Richard “Windy” Gale, the division commander, decides to seize the two bridges crossing the Orne River and Caen Canal intact.

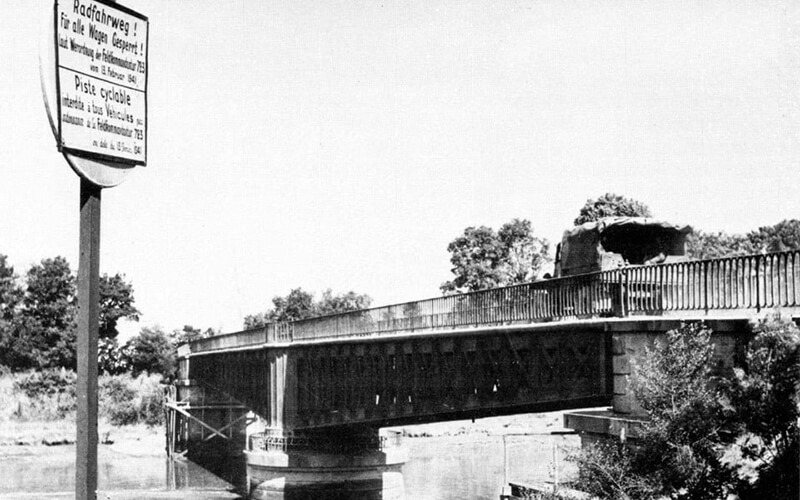

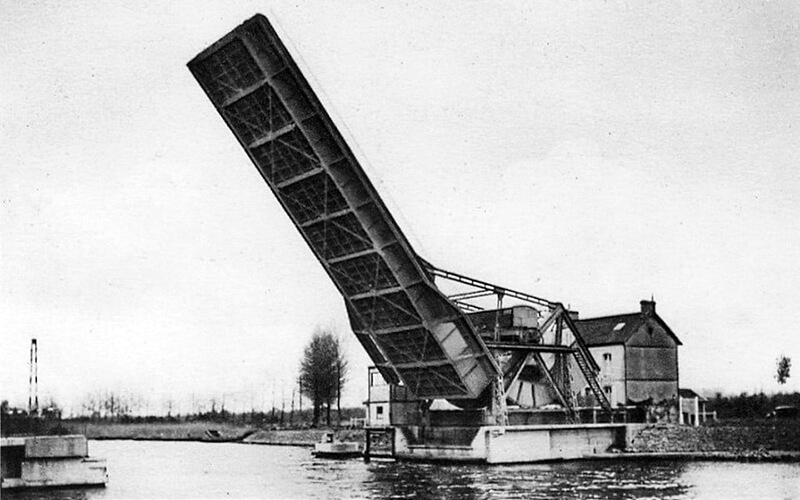

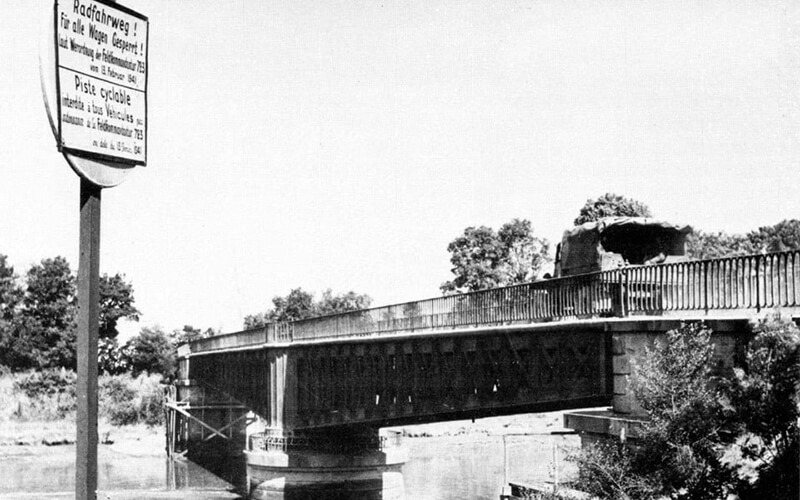

The Ranville bridge spans the Orne River, while the Bénouville bridge crosses the Caen Canal to the west of the river. These bridges are located eight kilometres from the coast and, as of June 1944, provide the only access to the city of Caen from the northeast. The main road crosses both bridges and continues eastward to the Dives River. The Caen Canal bridge, measuring fifty-eight metres in length and 3.8 metres in width, is designed to open to allow canal traffic to pass underneath. The controls are housed in a nearby cabin. The canal itself is 46 metres wide and 8.2 metres deep, with earth and stone banks 1.8 metres high on each side, each bank having small tarmac tracks running along the canal’s entire length from Caen to Ouistreham on the English Channel.

Between the two bridges lies a strip of mostly marshy ground approximately 500 metres wide, broken by ditches and small streams.

The Ranville bridge over the Orne River is 110 metres long and 6.1 metres wide and can also be opened to allow the passage of river traffic. The river is between 49 and 73 metres wide and has an average depth of 2.7 metres, with mud banks averaging about 1.1 metres in height and a tidal rise and fall of between 2 and 4.9 metres. Several small houses lie to the west of the river, and there is a track between 2.4 and 3 metres wide along both banks.

The bridge is guarded by fifty men of the 736. Grenadier Regiment of Generalmajor Ludwig Krug’s 716. Division, within SS-Obergruppenführer und General der Waffen-SS Josef Dietrich’s I SS Corps ‘Leibstandarte’. They are under the local command of Major Hans Schmidt and based at Ranville, 1.9 kilometres east of the Orne River. The 716. Division is a static formation assigned to Normandy since June 1942, with its eight infantry battalions deployed to defend thirty-five kilometres of the Atlantic Wall. The division is poorly equipped, using a mix of German small arms and an assortment of artillery and anti-tank weapons from stocks captured in earlier campaigns. It is manned by conscripts from France, Poland, and the Soviet Union, under German officers and senior non-commissioned officers. Schmidt’s detachment has orders to blow up the two bridges if they are in danger of capture.

A second formation, Generalleutnant Edgar Feuchtinger’s 21. Panzer-Division, moves into the area during May 1944. One of its key components, Oberst Hans von Luck’s 125. Panzergrenadier Regiment, is billeted at Vimont, just east of Caen. Additionally, a battalion of the 192. Panzergrenadier Regiment is based at Cairon, to the west of the bridges. Von Luck has trained his regiment specifically for anti-invasion operations, identifying likely incursion points and marking out forward routes, rest and refuelling areas, and anti-aircraft gun positions. The 21. Panzer-Division is essentially a new formation based on the previous division of the same designation, which was destroyed in North Africa in 1943. Although equipped with an assortment of older tanks and other armoured vehicles, the division’s officers are veterans, and there are some 2,000 veterans from the previous division in its ranks.

Farther afield are SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Waffen-SS Fritz Witt’s 12. SS-Panzer-Division “Hitlerjugend” at Lisieux and Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein’s Panzer-Lehr-Division at Chartres, both less than a day’s march from the area.

The Germans have fortified both bridges. On the western end of the Caen Canal bridge, there are three machine gun emplacements. On the eastern end, there is one machine gun emplacement and one anti-tank gun. To the north, there are another three machine gun emplacements and one concrete pillbox. An anti-aircraft tower equipped with machine guns stands to the south. At the Orne River bridge, the eastern bank has a pillbox with anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns to the south of the bridge, and two machine gun emplacements to the north. Each bridge also has sandbagged trench systems along its banks.

Since the two bridges are only five hundred metres apart, a glider assault is deemed the most effective approach. Gale confers with Brigadier Hugh Kenyon Molesworth Kindersley, 2nd Baron Kindersley of West Hoathly and commander of the 6th Airlanding Brigade, to get his opinion on the best company for this critical task. Kindersley recommends Howard’s company. To validate this choice, the division conducts a three-day exercise in March 1944, named Exercise Bizz. The purpose of this exercise is to validate the soundness of the coup de main concept and to determine the unit most likely to succeed in its execution.

| March 25th 1944 – March 27th, 1944, Exercise Bizz II |

D Company and the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry participate in a flying exercise of the 6th Airborne Division known as Exercise Bizz II. One of the purposes of this exercise is to validate the soundness of the coup de main concept and to determine the unit most likely to succeed in its execution. This exercise involves the greatest number of planes and gliders ever used in an exercise in the Great Britain. The whole 6th airlanding brigade, except for D Company, is lifted in Horsas, with either Albemarles or Stirlings as tugs, while the 3rd Parachute Brigade is lifted in Dakotas. The objectives are to test the air planning and the division in a typical operational role.

The north coast of France is represented by the line of the road running south from Banbury, all west of this line is considered to be Northern France. Typical enemy dispositions are laid out, and detailed intelligence summaries are produced, conforming almost entirely to the latest information about German positions in areas where the division might be expected to operate when the invasion begins. The bridgehead is to be formed by V Corps occupying the area Banbury-Lechlade-Shifford, with the initial seaborne landings taking place at 06:30 on D-Day, the March 26th, 1944. The coast south of the projected bridgehead is to be attacked by a special service brigade to neutralise coastal defences, while the 6th Airborne Division lands in the area of Faringdon, with the 6th Airlanding Brigade to the north and the 3rd Parachute Brigade to the south. Specific tasks include seizing and holding intact, until relieved by V Corps troops, the bridges at 7319 and holding the area Aston Pill-Littleworth-Faringdon by the 6th Airlanding Brigade, while the 3rd Parachute Brigade seizes and holds the high ground at Badbury Hill and destroys the medium battery at 7312 before first light on D-Day. The airborne division is to land during the evening of D-1 day. The Regiment is allotted thirty-seven Horsas and takes off from airfields at Keevil, Fairford, and Brize Norton at 16:30.

All gliders land at Brize Norton at approximately 19:00, following a route south over the coast at Bournemouth, east over the sea to Lulworth, and back northeast to the landing area. Three gliders experience slight mishaps and make forced landings, one of them in the sea, losing valuable cargo, although all on board are rescued. This glider makes a good landing, and all occupants climb out onto the wings and remain there until picked up by a Walrus air-sea rescue plane, which taxis them to a naval launch. The passengers include the adjutant, medical officer, padre, regimental serjeant-major, and two privates from the Regiment, together with a wing commander, Royal Air Force, two glider pilots, two driver-operators from the Royal Signals, and one Royal Army Medical Corps orderly. Although they all suffer from shock and are badly shaken and bruised, none are seriously hurt. The other two gliders make forced landings some distance from the landing zone. This experience proves valuable for commanders, showing how things can go wrong in action and necessitating modifications to their plans due to being short of troops and supplies.

After landing, the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry makes its way to the rendezvous by individual glider. Before the battalion lands at Brize Norton, D Company crash-lands (by troop-carrying vehicles) on the objective with the task of capturing the bridges and holding them until the Regiment arrives. The reconnaissance platoon moves ahead, attempting to locate D Company’s position. When contact is made, it finds that the enemy has been driven off, but a counterattack is expected. The 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry advances towards the bridges, and B Company successfully repels the enemy counterattack at 23:30. The battalion then takes up a defensive position at the bridges, digging in for all-round defence, and prepares to await the arrival of V Corps.

At 15:30, V Corps advance guard arrives, and the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry moves to a recently evacuated enemy position at Coleshill. Here it digs in again and maintains an offensive patrolling policy throughout the night. Patrols gather valuable information about enemy movements and strength, preparing the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry for a strong attack that develops later in the morning. Using tanks, the enemy overrun part of the battalion’s area, but several counter-attacks ultimately force the enemy to retire, restoring the battalion’s position. Although they still hold the same ground, they are very depleted in strength. This marks the end of the first full-dress rehearsal for the invasion, though few realise the full significance at the time. Valuable lessons are learnt, especially by D Company in its assault on the bridges, with points brought out by the exercise proving invaluable during later planning. Major General Gale and Brigadier Kindersley are particularly impressed with the performance of D Company of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, led by Major Reginald John Howard.

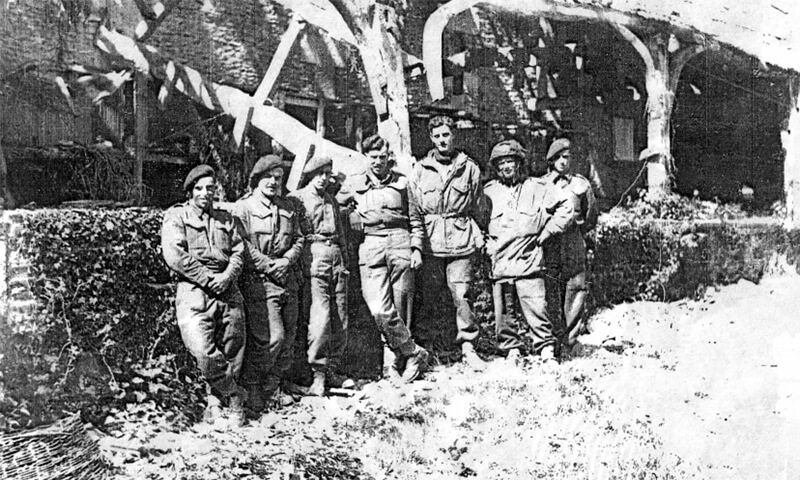

| The Glider Pilots |

In early March 1944, six glider crews from various flights of the Glider Pilot Regiment are assembled at Netheravon Airfield without explanation. They are addressed by Colonel George Chatterton, accompanied by high-ranking army and air force officers. Two landing areas marked with white tape are pointed out on the airfield, one for the first three gliders and the other for the remaining three. The briefing is brief: the gliders will be towed to 1,200 meters at one-minute intervals, released five kilometers away to land in their designated triangles. After a lunch break, they are scheduled to take off at 13:00.

The selection process for the crews is unclear, possibly random, and all are sergeants. Staff Sergeant Jim Wallwork, with co-pilot Staff Sergeant Johnnie Ainsworth, is designated to fly first and consistently remains as number 1 during the training. Despite initial doubts, all six gliders successfully land in their correct areas, surprising the observing officers. The next day, the exercise is repeated with the same successful result, solidifying the operation’s viability.

This marks the start of Operation Deadstick, the codename for the glider pilot training. During the initial trials at Netheravon with Albemarles the need for a more powerful tug is quickly revealed to get a fully loaded Horsa glider up to 1,800 meters in under an hour. Consequently, the operation moves to Tarrant Rushton Airfield, where No. 298 and 644 Halifax Squadrons are based. For the first time, crews are paired with their tugs for the entirety of the training and final operation, fostering confidence and camaraderie.

Training is initially haphazard, with daylight tows scheduled during quiet periods at the busy Tarrant Rushton airfield. The new operational height is set at 1,800 meters, and two distinct flight paths are developed: gliders 1-3 follow a triangular route, while gliders 4-6 fly a dog-leg pattern. Towed at one-minute intervals, gliders 1-3 fly downwind for 3 minutes and 40 seconds at 145 kilometers per hour (90 mph), then execute a 90-degree right turn for 2 minutes and 5 seconds, followed by another 90-degree turn to align with the target. Gliders 4-6 follow a similar pattern but use flaps to adjust their descent directly towards the target.

As it becomes impractical to operate solely from Tarrant Rushton, a new target area is selected: “Holmes Clump,” an L-shaped wood near Netheravon Airfield. Conveniently located, gliders landing there can be towed back to Netheravon airfield by tractor. This area becomes central to Deadstick training. Fourteen glider pilots (six crews and a backup) are housed in a Nissen hut at Tarrant, led by a Lieutenant. The training operation is directed by Royal Air Force pilots Flight Lieutenant Tom Grant and Keith Miller, who manage all briefings, courses, wind calculations, and timings.

During flights, the procedure is to cast off at 145 kilometers per hour while turning onto the designated course. The co-pilot starts the stopwatch, and the narrator executes a controlled Rate One right turn to the second course at the countdown’s end. This process is repeated to align with the target. The only significant incident occurs when glider number 6 lands late with a loud crash, resulting in minor injuries but no fatalities, underscoring the need for a backup crew.

| April 15th, 1944 |

At the de-briefing for Exercise Bizz, Major General Gale highly praises Major Howard and his company. Following the de-briefing, Howard’s battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Michael Roberts, informs him of the true purpose of the exercise. He tells him that D Company, reinforced with two additional platoons. and thirty Sappers under command, are to have a very important task to carry out when the invasion starts. The Colonel goes on to tell him that their task will be to capture two bridges intact.

Lieutenant Colonel Roberts informs Howard that his unit’s mission is classified top secret and orders him not to share it with his subordinates yet. He tasks Howard, and the reinforced D Company, with capturing bridges during the corps-level Exercise Mush, which takes place at the end of April 1944. With this specific mission in mind, Exercise Mush provides Howard with several crucial lessons for the development of the assault plan.

Howard selects the extra platoons from B Company, commanded by Lieutenants Dennis Fox and Richard ‘Sandy’ Smith from B Company. Planners initially estimate that four platoons would suffice, two for each bridge, but, on Gale’s orders, an extra platoon is added for each bridge as insurance against casualties or the loss of a glider, a prudent decision.

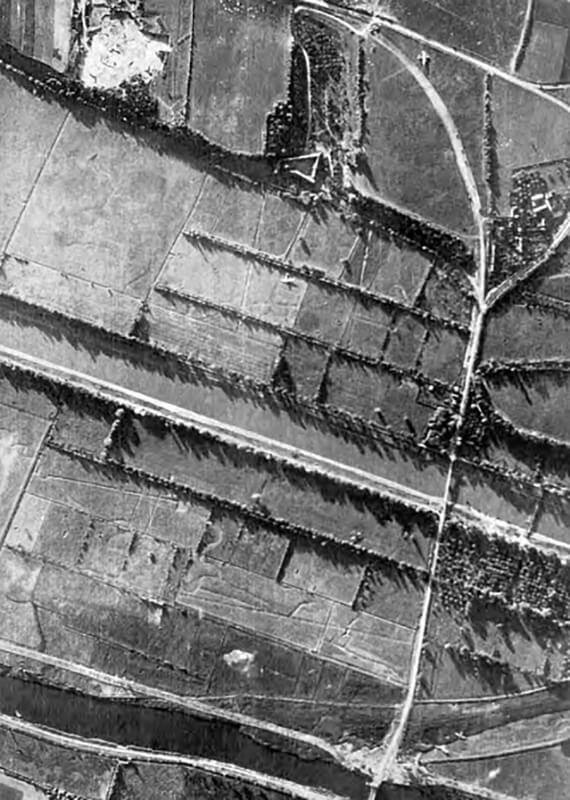

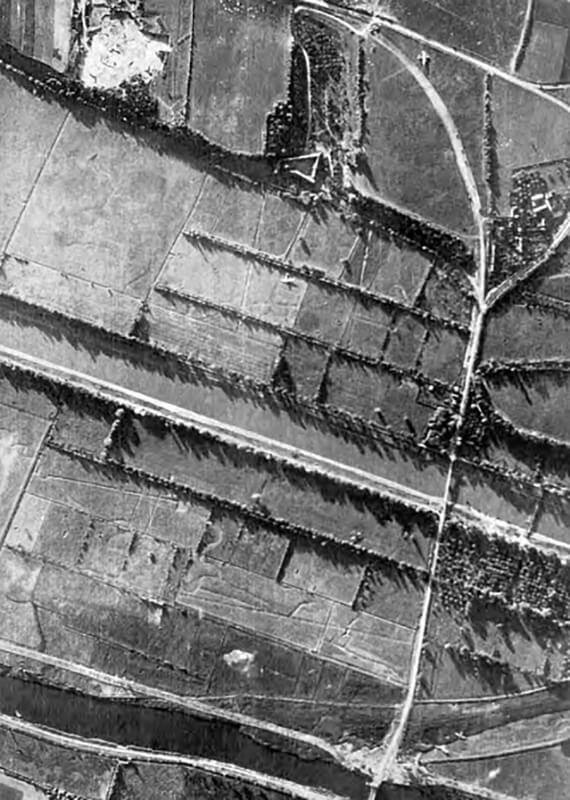

Howard identifies two potential landing zones for the gliders, codenamed LZ-X and LZ-Y. LZ-Y, to the east, is a long four-sided field bordering the River Orne to the north of the bridge. LZ-X, to the south of the Caen Canal bridge, is more hazardous, with a line of trees to the west and an unknown swampy pond to the east. The landing zone is triangular, tapering to a point by the bridge. Howard selects these zones to ensure his force lands between the river and the canal, preventing them from being stranded if a bridge is destroyed. He also decides to make each glider load a self-contained unit, comprising both engineers and soldiers, so that a single glider crew can capture and hold a bridge while the sappers neutralise the charges.

As planning progresses, Howard is kept up to date with the latest reconnaissance photographs. The key to capturing Bénouville Bridge involves neutralising the bunker on the right bank of the canal. Three men from the lead section of 25 Platoon, in the first glider, will throw grenades through its embrasures, while the rest of the platoon rushes across the bridge to seize the western end. Close behind, 24 Platoon will clear remaining positions on the right bank, and 14 Platoon, in the last glider, will cross to reinforce 25 Platoon. The same procedure is planned for Ranville Bridge, with 22 Platoon taking the eastern end, 23 Platoon clearing the western end, and 17 Platoon consolidating the defences upon landing.

Reinforcements will come from the 7th Battalion, 5th Parachute Brigade, 6th Airborne Division, landing in drop zones between the River Orne and the River Dives at 00:50 Brigadier Poett, commanding 5th Parachute Brigade, assures Howard that organised reinforcements will arrive within two hours of touchdown. The paratroopers will move through the village of Ranville, where Poett will establish his headquarters for the defence of the bridges.

| Training |

Immediately after being assigned this mission, Major Howard implements a rigorous and realistic training regime. He is satisfied with the company, both in terms of its officers and men, many of whom are easy-going yet confident young Londoners. In training, Howard demands nothing less than first-class standards of fitness. He also takes his responsibility as a commander very seriously, abstaining from drinking to keep a clear mind.

The battalion undergoes three weeks of intensive training at Ilfracombe in Devon. At the end of this period, the men march back to Bulford Camp on Salisbury Plain, a distance of 210 kilometres, carrying 36 kilograms of weapons and equipment. The march takes place in two days of pouring rain and two of blistering heat. Despite the toughness and blisters, they all start singing upon reaching the barracks. They complete the march in only four days. Major Howard insists that officers do not return to their quarters and take off their boots until they have ensured that all their men’s feet have been inspected and any men with bad blisters are sent to the medical inspection room. Only then are officers allowed to tend to their own needs. This emphasis on looking after the men above all else is drilled into them, and it is the company’s performance on the ‘Great March’ that clinches its role as the coup de main force for the bridges.

Training includes street fighting tactics taught in bombed-out and evacuated parts of British cities, and the men also learn the skills of unarmed combat. Essentially, Howard is taking men from an ordinary British infantry regiment and, with good training, quietly turning them into special forces.

To make the training more realistic, Howard requests an area in Britain with conditions similar to those in Normandy. A suitable location is found south of Exeter, where the A38 crosses the River Exe and the Exeter Canal at Countess Wear. Howard moves his men to Devon, where they practise attacks day and night for almost a week. These exercises are conducted under the eyes of many curious onlookers from the surrounding area, some of whom interfere with proceedings. One local resident is angry that several tiles have been blown off his roof by an exploding grenade, and the town council feels the exercises are weakening the bridges. They also disapprove of the soldiers fishing with No. 36 grenades.

Howard prepares his men for every conceivable eventuality on the ground, such as only one glider reaching the bridges or others falling short. In case all the sappers in the coup de main force become casualties, Howard makes his men fully familiar with locating and neutralising demolition charges. They even learn how to handle assault boats, to be used if either of the bridges is blown.

In early May, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel inspects the bridges and orders the construction of Tobruk anti-tank gun emplacements, protected by barbed wire and a bunker. Within 48 hours, the Royal Air Force reconnaissance detects this work, and the French Resistance provides a detailed description a week later.

During that same period, Brigadier Nigel Poett assures Major Howard that he can have anything he wants. All he has to do is ask. One notable request is for ‘German’ opposition for their exercises, meaning opponents dressed as Germans, carrying German weapons, and even speaking German. This is arranged, and the coup de main force makes a thorough study of German weapons and becomes familiar with their use. Besides Howard, no one in the company knows the reason for the constant focus on capturing bridges, leading some to boredom. Howard takes the men into his confidence and assures them: “We are training for some special purpose. You’ll find a lot of the training we are doing, this capturing of things like bridges, is connected with that special purpose. If any of you mention the word “bridges” outside our training hours and I get to know about it, you’ll be for the high jump and your feet won’t touch the ground before you are Returned To Unit.”

| Exercise Mush |

In May 1944, the 6th Airborne Division mounts a pre-invasion exercise named Exercise Mush. Howard’s coup de main force is ordered to capture a bridge across the Thames at Lechlade in Gloucestershire, held by men of the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade. Instead of gliders, the company is driven to the general area of the bridge in trucks. The men of the Ox and Bucks then march to a point within metres of the bridge, representing their glider landing zones, and lie low until a signal indicates they have ‘landed’. Upon receiving the signal, Howard’s men and their supporting sappers move silently forward to the bridge. An umpire is present and, although the company captures their objective, he rules that they have not, and the bridge has been blown. The Poles provide spirited resistance. Lieutenant Hooper of 22 Platoon argues furiously with the umpire, but to no avail. More seriously, in the darkness, there is a “blue on blue” (friendly fire) incident between two platoons, resulting in heavy casualties according to the umpires. The role of the coup de main force in Mush ends in failure. However, valuable lessons are learned about the tactics required to capture a bridge. The experience of the “blue on blue” incident leads to the adoption of platoon radio call-signs as a simple form of identification. On the night of the attack, men will shout the phonetic alphabet letter identifying their platoon, Able or Baker, for example. Fortunately for Lieutenant Fox’s platoon, their identifying shout will be Fox.

| May 25th, 1944 |

The reinforced company climbs into its trucks and prepares to leave the battalion camp at Bulford. The rest of the regiment turns out to watch them depart. They knew they were going on some special operation. They didn’t know what. The assault force moves to a sealed transit camp with a barbed wire perimeter guarded by Military Police, cutting the men off from any communication with the outside world. Inside this secure compound, like thousands of other troops destined to land on D-Day, they are told of their destination and learn the reason behind the intense training they have undergone in the preceding months.

| May 27th, 1944 |

Brigadier Kindersley visits the unit and informs Major Howard that he can brief his men about the Coup de Main. That same morning the officers of the reinforced company enter the heavily guarded briefing room, and everything is covered up. After making a bet proposed by Major Howard where they were going to land, Howard gives the order to strip off the paper, and maps, aerial photographs, and the detailed model are revealed. Major Howard then goes through his plan again: how we are going to land and what we will do. A 3.6 metres by 3.6 metres scale model is created, showing every detail of the bridge, and updated daily based on new reconnaissance. The mass of detailed intelligence they receive is remarkable. They learn the strength of the enemy, where the nearest Panzers are, what to expect, who is coming behind, how many soldiers and how many anti-glider poles there are and when the last one has been put up or how many new holes have been dug. They even know the name of Georges Gondrée in the café owner and that he speaks English.

Several briefings are held, and both the officers and Howard address the individual platoons and even sections. Major Howard encourages his men to use a hut where all the maps and photographs are on display, asking them to study everything in detail and then discuss any ideas that could be added to the plan.

General Gale speaks to the men at Tarrant Rushton, delivering a robust morale-boosting briefing. He explains the prospect facing the German garrison of the Atlantic Wall: “The German today is like the June bride. He knows he is going to get it, but he doesn’t know how big it is going to be.”

The fourteen specially selected glider pilots have been training for this specific mission for months have joined the unit. Their training consisted of forty-three training flights in different weather conditions, with night and instrument flying, using stopwatches for accurate course changes. The glider pilots, who have been practising their skills on carefully demarcated landing zones on the British Army training area on Salisbury Plain, are concerned that their aircraft will be overloaded. The leader of the Sapper’s group, Jock Neilson, weighs one of his men fully loaded for action and finds, to his horror, that the man weighs 135 kilograms instead of the allowed 110 kilograms. Neilson immediately reports this concern to Major Howard. He dresses one of his man in full combat equipment and finds out that the man weighs 110 kilograms instead of the average allowance of 95 kilograms for an infantryman.

As a result, each of Howard’s platoon commanders has to tell two of their men that they will not be going on the operation but will rejoin the company after they have landed. However, despite these efforts, the gliders remain too heavy.

It is also recognised that bringing seven tons, the combined weight of three tons of troops and the three and a half-ton glider, down into a small field from 1,800 metres and bringing it to a stop is quite challenging. Although the glider excels in short landings using full flaps, there remains the problem of fitting three gliders, or even one, into that field with the landing run, especially with two more gliders following closely behind. Consequently, the decision is made to install drag chutes. This idea is proposed by Flight Lieutenant Grant, who observed the Americans using them during trials in the United States.

| June 2nd, 1944 |

During the night, a team of Airspeed engineers, equipped with mobile workshops, arrives at Tarrant Rushton Airfield and begins modifying the six gliders. An arrester parachute is fitted into each tail. To unload the Mk 1 Horsa glider, there is a double bulkhead aft of the trailing edge of the main planes, featuring six quick-release bolts to drop the tail out of the way. This section includes a panel on the lower part of the fuselage that can be lowered to attach a rifle or other weapon for use upon landing.

The parachute, connected to the bulkhead, is placed in a box on this panel and can be operated from the cockpit using toggle switches in the centre of the instrument panel. One switch opens the trap door for the chute to fall out and deploy, while the other operates the release mechanism to discard the parachute. The Glider Pilots are concerned because, with the parachute lying on a loose panel on the floor, turbulence might cause the panel to be sucked out, leading to the parachute deploying while being towed across the Channel. Therefore, it is decided that the Ox and Bucks or the engineer sitting in the rear seat of the glider will keep the parachute on their lap during the flight over the Channel. Once they have cast off, they will lean over the back of their seat and place the parachute onto the panel, positioning it for deployment.

A few days later, it is suggested that the company should have a medical officer on board because they are going into action completely alone. Consequently, Captain Dr. John Vaughan Royal of the 224th Field (Parachute) Ambulance, Army Medical Corps is included, meaning another man must be left behind. Fortunately, a soldier who has sprained his ankle in a tough game of football is excluded.

The constant stream of intelligence keeps the soldiers and glider pilots up to date with changes around the bridges. Major Howard is worried by the increasing appearance of anti-glider obstacles, nicknamed Rommelspargel (Rommel’s asparagus) by the German troops. These are thick poles or logs driven vertically into the ground and spaced at intervals of 5–12 metres. Some are linked to mines fitted with pull switches so that if a glider crashes into the poles, it will trigger the mines. These obstacles are supplemented by the flooding of low-lying farmland. The flooding proves highly effective against paratroopers, who, heavily laden, find themselves stuck in the sticky underlying mud. While some of the construction of these obstacles and defences is undertaken by German troops, the main burden falls on slave labour or prisoners of war.

Major Howard becomes concerned when he sees a regular pattern of holes appearing around the landing zones, indicating that anti-glider obstacles will soon be erected. In the finest tradition of pilots, both commercial and military, the glider pilots assure their passengers that all is well, and any worries are groundless: the obstacles will not pose a problem. Staff Sergeant Geoffrey Barkway and Staff Sergeant Jim Wallwork claims that if he would aim the glider straight between the posts, he might lose one wing or the other, but they would go straight through, and they’ll help them, slowing down the Horsa.

| June 4th, 1944 |

At 09:00, Major Howard is handed a brown envelope by a dispatch rider. Opening it, he reads the brief message that includes the code word “Cromwell”. It confirms that D-Day is on. But now the weather closes in, and by the afternoon wind and heavy rain lash the camp. It is perhaps ironic that the camp cinema is showing the American musical Stormy Weather, starring Lena Horne. In the mess tent, Fox watches one of the attached airborne engineers take hold of the tent pole and raise himself parallel to the ground using only the strength of his hands and wrists. Even though the camp is ‘closed’, Fox and Wood manage to slip out and have a beer and dinner with their girlfriends.

| June 5th, 1944 |

The morning is much brighter, and the men are informed that it is “on” for that night”. The company has a day of rest. Sleep, however, is out of the question, the men are all too keyed up. A service is held in the afternoon by Oxf and Bucks Padre, Captain Nimmo.

The men have their final meal, a special non-greasy one. After which they are stuffed with goodies. They receive little packs with maps, Benzedrine tablets, glucose, and money, French, German, Dutch, and Belgian currencies, in case we get lost. We have maps of Europe imprinted on silk handkerchiefs so that we can stuff them in our pockets, a compass sewn onto the fly of our trousers, and files sewn into our battledress pockets to saw their way out of prison. As they sort their equipment, some men decide to have their heads shaved, not as bravado but as a precaution against infection if they suffer a head wound.

That evening, about 20:00, The men check their equipment, load their personal weapons, and board the vehicles transporting them to the airfield. When they arrive at Tarrant Rushton, dusk is just falling. They drive directly to the Horsa’s and sit on the grass beside them, chatting to the glider pilots. Some kind soul appears with a large cooking pot of tea. It has a good mixture of rum in it.

Chalk is acquired, and the fuselages of the Horsa gliders are soon covered with confident graffiti such as “Adolf, here we come!” and “Lady Irene”. Just before the men boarded their gliders, codewords are issued: “Ham” and “Jam” indicates that the canal and river bridges respectively have been taken intact, while “Jack” and “Lard” indicates the capture but destruction of the canal bridge and river bridge, respectively. As the men enter the Horsa at 22:30 they hear cries of “Good luck!” from various onlookers. The pilots’ concerns about the weight are justified. They have calculated that each man with his weapons and equipment weighs approximately 109 kilograms. A bren gunner kit, includes ‘four Bren magazines, two bandoleers of .303 ammo, six Mills grenades, two No. 77 phosphorus smoke grenades, two Norwegian stun grenades, a 24-hour ration pack consisting of tea cubes, soup, oatmeal, toilet paper, sweets, matches, and fuel for the little Tommy cookers, a Hawkins anti-tank grenade, and a flotation Mae West with two oxygen cylinders attache’. Those men armed with the Sten sub-machine gun carry the superior Sten Mk V, a well-machined weapon with a wooden stock, pistol grip, foregrip, and the capability to be fitted with the No. 4 rifle bayonets. In addition to the men, the gliders are loaded with ‘boats and inflatable rafts and Bangalore torpedoes, because of the idea that they would have to blow their way through barbed wire.

Major Howard watches as the men prepare to board the gliders. The platoon commanders sit at the front close to the pilots, while the platoon sergeant scrambles in last by the rear door. The men are in good spirits. Major John Howard comes along and wishes everybody well. They can all feel the emotion in his voice. As the glider doors close, the men now sit in a world of their own.

The first Horsa is airborne at 22:59. The second, is up at approximately 23:00. The remaining Horsa’s follow at one-minute interval. The success of the mission is now in the hands of the tug crews and the six pairs of glider pilots.

| Underway |

Staff Sergeant Jim Wallwork, the pilot of Horsa No. 1, anticipates casting off because, in the light of the full moon through the clouds, he glimpses the surf breaking on the Normandy coastline. Beside him, his co-pilot, Staff Sergeant John Ainsworth, concentrates intensely on his stopwatch. Sitting behind Ainsworth, Major Howard, who suffers from airsickness and has vomited on every training flight. However, has not been sick this time. Like his men, this is the first time he will be in action, and the prospect has calmed his troubled digestion.

Inside the lead glider, everybody starts singing. The vast majority of them are Londoners, and they are mostly London songs, “Roll Out the Barrel” and “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles”. At the rear of the glider, Corporal Jack Bailey sings, but he also worries about the parachute brake he might be required to operate. Horsa’s have been fitted with a rear hatch from which, in theory, a Bren gunner can engage hostile aircraft pursuing the glider; for the Coup de Main, this has been modified to take an arrester parachute to provide, theoretically, a safer, slower descent just before landing.

One minute behind Wallwork’s glider is No. 2, flown by Staff Sergeant Oliver Boland, carrying Lieutenant David Wood’s 24 Platoon into action. Another minute behind it is No. 3, with Lieutenant Richard “Sandy” Smith’s 14 Platoon. These three gliders are set to cross the coast near Cabourg, well to the east of the mouth of the River Orne. Parallel to that group, to the west and a few minutes behind, Captain Brian Priday sits with Lieutenant Tony Hooper’s 22 Platoon, followed by the gliders carrying Lieutenant H. J. ‘Todd’ Sweeney and 23 Platoon, and Lieutenant Dennis Fox and 17 Platoon. This second group heads towards the mouth of the Orne.

At 00:07, Staff Sergeant Wallwork releases the nylon towline from his tug aircraft as he crosses the coast near Merville. There is a sudden jerk aboard each glider, the singing stops, and the roar of the bombers’ engines fades. The silence is broken only by the rush of air over the Horsas’ wings. As clouds cover the moon, Ainsworth uses a pocket torch to see his stopwatch, which he has started with the cast-off. The first leg of the flight is between 10 and 11 kilometres and will take only three and a half minutes.

Wallwork is flying blind, unable to see the bridges or even the river and canal reflecting the moonlight. He relies on his co-pilot, John Ainsworth, who watches his stopwatch while they both monitor the compass, airspeed indicator, and altimeter. Three minutes and 42 seconds into the run, Ainsworth says, “Now!” and Wallwork puts the Horsa into a full turn to starboard.

Around and below them, it is still clouds and darkness. Wallwork says, “I can’t see the Bois de Bavent.” This large area of woodland should be visible to the pilots on the port side of the glider. Ainsworth, irritated, insists it’s the biggest place in Normandy and tells Wallwork to pay attention. Wallwork insists it isn’t visible. Ainsworth reassures him they are on course and starts counting down for the next manoeuvre. Wallwork turns the glider north, descending rapidly from 2,100 metres to about 150 metres, reducing airspeed from 260 kilometres/hour to about 180 kilometres/hour.

Behind them, flames, searchlights, and tracer fire over Caen are faintly visible. Ahead, they still see nothing.

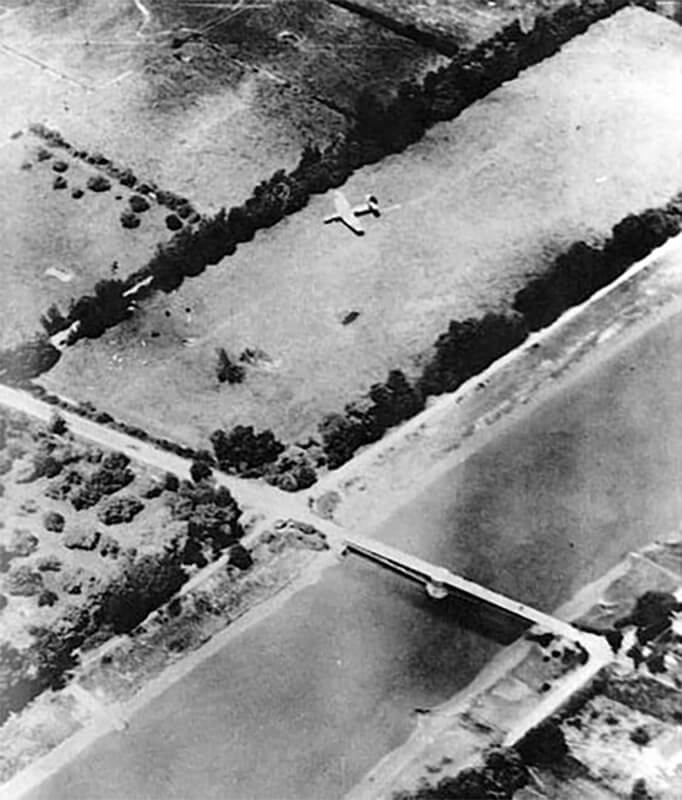

Their target is a small triangular field, about 450 meters long, near the southeast end of the canal bridge. Though Wallwork cannot see it, he has memorized photographs and studied the model of the area extensively. Training included a film made with a small cine camera on a curved wire replicating the Horsa’s downward flight path.

Suddenly, the bridge comes into view, with its superstructure, water tower to the east, and flat landscape. Wallwork notes the machine-gun bunker north of the bridge, the anti-tank gun Tobruk across the road, and the surrounding barbed wire.

During the final briefing, Major Howard had told Staff Sergeant Wallwork to aim for the nose of the Horsa to break through the barbed wire. Wallwork had his doubts about landing the heavily overloaded glider with precision, at midnight, over an untested landing strip. However, he assured Howard he would do his best. Wallwork and Ainsworth had privately agreed that such a landing might result in broken legs.

Wallwork has other concerns: at 145-160 kilometres/hour upon impact, hitting a tree or an anti-glider pole would be fatal, incapacitating the men aboard. The parachute brake in the back of the glider adds another worry, as its deployment might pitch the nose forward, causing a vertical dive. The control for the parachute is above Ainsworth’s head; he will deploy and release it at the proper moment.

At 00:14, Wallwork signals to Major Howard to get ready. The men link arms and lift their feet to prevent injuries during landing. Wallwork maintains focus as they descend.

The Horsa lands at about 145 km/h on rough ground. The parachute brake deploys, slowing the glider amidst jolts and skids.

| Bénouville bridge over the Caen Canal |

At 00:16, Staff Sergeant Wallwork lands Horsa No. 1, carrying Major Howard, Lieutenant Brotheridge, and 25 Platoon. The Horsa skims the tall trees at the end of the field and came into land in more of a controlled crash. Both the glider pilots realise that the Horsa has lost the wheels and landed on the skids. Briefly, the glider seems to bounce, and they are airborne again for a second or two. Then they hit the ground once more with another enormous crash, rose briefly and came down for a third and final time. The glazed nose of the glider comes to rest against a barbed wire fence, forty-five metres from the bridge. The abrupt halt catapults the two pilots from their seats, smashing through the cockpit windscreen. Behind them, the platoon is stunned for a few seconds. Howard’s seatbelt breaks, causing him to hit his head on the roof, forcing his helmet down over his eyes. When he regains consciousness, he experiences the terrifying sensation of being sightless, wondering if he is dead or blinded. A quick tug at his helmet rim resolves the problem.

There is still no firing from the Germans on the bridge. In fact, the sentries on watch have heard the crash landings and thought they were something that had dropped from one of the bombers. They are just looking around in bewilderment. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Herbert Denham “Den” Brotheridge has the door of the glider open and shouts to a Bren gunner, “Gun out!” after which he around to join Major Howard who realises that he is limping. Howard asks if he is OK, and Brotheridge replies that he is OK. After which Major Howard gives the command to get cracking with the first section. Brotheridge runs off in the direction of the bridge with his platoon in close pursuit to tackle the first task: securing the area on the other side.

Almost immediately, one man lobs a phosphorus bomb at the pillbox across the road to give cover for Corporal Bill Bailey’s leading section to run in and drop thirty-six grenades through the slits. While this is happening, the rest of the platoon charges across the bridge. Lieutenant Brotheridge limps as he runs but is oblivious to the pain in his leg, firing from the hip as he goes.

Major Howard and his wireless operator, Lance Corporal Ted Tappenden, begin making their way towards the bridge to establish a command post inside a trench near the perimeter wire. The moment they appear over the embankment, firing starts. As they advance, Major Howard watches Lieutenant Den Brotheridge and his platoon dash across the canal bridge, with Brotheridge courageously leading at the front. An automatic machine gun, alerted to their position, opens fire on Tappenden and Howard from the trenches across the road, forcing them to dive for cover. Just then, Howard hears the distinct sound of a Spandau machine gun firing at Brotheridge and his platoon from the direction of the café on the other side of the canal.

Almost simultaneously, Howard hears the familiar calls of ‘Charlie, Charlie, Charlie’ from Lieutenant Wood’s platoon. Wood himself emerges from the darkness, panting. His platoon is ready for action, and Howard quickly orders them to carry out task No. 2. They immediately move in, firing from the hip to clear the inner trenches on their side of the canal. The air is filled with gunfire and explosions. The calls of each platoon identifying themselves can be heard above the sound of gunfire, with stray bullets whipping past and tracer rounds creating patterns in all directions.

Just then, Platoon Leader Sandy Smith from No. 3 Glider informs Howard that they have had a bad landing and sustained some casualties. Smith, with a broken wrist and his arm tucked into his battledress, receives a quick briefing from Howard. Smith’s task is to cross the bridge and reinforce Brotheridge’s platoon, taking the right side of the road and leaving Brotheridge to the left. Shortly after sending Smith off, Howard is informed that Brotheridge has been hit in the neck by machine-gun fire and is badly wounded. Howard’s first instinct is to check on his friend’s condition, but as the Commanding Officer, he knows he cannot leave the command post without leaving another officer in charge. This realization is compounded by the fact that he has heard nothing from the river bridge, where his second-in-command, Captain Brian Priday, is supposed to have landed.

Tappenden confirms that he has heard nothing over the wireless, raising concerns that the set may have been damaged in the landing. Howard considers sending a runner to check on the situation at the river bridge, but just then he is informed that both David Wood and his platoon sergeant are out of action, having run into machine-gun fire from the trenches. Howard suddenly realizes that within a few minutes of landing, he is left with only one infantry officer, Sandy Smith, who is operating with just one functional arm.

A flare hangs in the sky as Lieutenant Brotheridge, leading the men of 25 Platoon, dashes across the bridge. On the far side, he crashes to the ground, caught in a burst of machine-gun fire. Crossing the bridge, Private Parr sees someone lying in the middle of the road. He looks at him and go to run on but stop dead, comes back and kneels down. It is Lieutenant Brotheridge. Private Parr just kneels down beside him. His eyes are open, and his lips are moving. Private Parr just looks at him. He can’t hear what it is. He put my hand behind his head to lift him up. His eyes roll back, he just chokes and lies back. It had only taken twenty or thirty seconds, for Lieutenant Brotheridge to die. The first man to die on D-Day. (Disclaimer. In Major Howard’s account of the events surrounding Lieutenant Brotheridge’s death, he notes that he checked Brotheridge’s pulse when he was taken away by stretcher bearers and found him still alive but unconscious. Howard later writes that Dr. Vaughan informed him that Lieutenant Brotheridge had died. This sequence of events suggests that Lance Corporal Greenhalgh might have been the first man to die on D-Day, rather than Lieutenant Brotheridge.)

Apart from the firing going on, a great deal of noise emanates from platoons shouting codenames to identify friends in the dark, and there is an unholy babble of “Able-Able-Able”, “Baker-Baker-Baker”, “Charlie-Charlie-Charlie”, and “Sapper-Sapper-Sapper” coming from all directions. On top of automatic fire, tracer, and the odd grenade, it is hell let loose and most certainly would have helped any wavering enemy to make a quick decision about quitting,’ recalls Howard.

Horsa No. 2, piloted by Staff Sergeant Oliver Boland and carrying Lieutenant David Wood and 24 Platoon, comes in a minute later, landing a few yards away. After being told to Brace for impact by Lieutenant Wood the men all link arms and lift their feet off the floor. As they go in at a steep angle, they just wait. Feeling the jerk of the parachute opening, after they hit the ground with an almighty thump, rise into the air again, and suddenly come to an abrupt stop. The Horsa seems to break in half as it lands. The very violence of hitting the ground throws us forward, breaking our safety harnesses. I am propelled through the wrecked side of the Horsa to land flat on my back. Several other members of the platoon are in a mass of bodies alongside, including Lieutenant David Wood, still clutching his canvas bucket of grenades.

After reporting to Major Howard, the men quickly begin to clear the trenches. They find an MG34 intact with a complete belt of ammunition on it, which nobody has fired. There is a lot of firing going on and a lot of shouting. The men clear the trenches on the other side very quickly and see some boxes of ammunition and mines and things, but nothing really in the way of strong opposition.

Finally, aboard Horsa No. 3, the youthful Lieutenant Smith, commanding No. 14 Platoon, B Company, has Captain Dr. John Vaughan, who trained as a paratrooper, aboard. Vaughan keeps thinking, why he doesn’t have a parachute?

At the controls of the Horsa, Staff Sergeant Geoffrey Barkway faces the prospect of landing on the tiny Landing Zone on which there are already two gliders. Incredibly, he places Chalk 93 between them, but as the scar across the ground and the shattered fuselage testify, it is a very heavy landing. The glider breaks up on landing, finishing up on the edge of, and partly submerged in, a pond. Both pilots are thrown through the smashed cockpit and into the water. Staff Sergeant Geoffrey Barkway, soaked to the skin, regains consciousness, and struggles back through the water to the glider on the bank. He sees the body of one of the men in the wreckage, but in his confused state, his only thought is to find the PIAT gun and get it to the command post. What no one realises is that there is an area of swampy water close to the Landing Zone, and tragically, Lance Corporal Greenhalgh, semi-concussed from the landing and burdened with equipment, drowns in the marshy pond.

Staff Sergeant Boyle, also confused from the crash, does not initially see Barkway but also notices the body of the dead lance corporal. Still disoriented, both men set off to find a stretcher bearer for the casualties. Staff Sergeant Barkway is then hit by a burst of machine-gun fire, which almost severs his arm just above the wrist. His recollections become understandably hazy as he is put on a stretcher and taken to the casualty command post. He later loses his arm. Boyle continues to help with the unloading of ammunition from the glider.

As the glider hits the landing zone, Lieutenant Smith knows they are in trouble because there are several seconds between that first bounce and the next. On impact, Lieutenant Smith shoots straight past the two pilots and through the perspex. He lands in front of the glider.

As the young Lieutenant struggles to his feet, groggy from the violent landing, one of his section commanders, Lance Corporal Madge, brings him to his senses by asking him what they are waiting for. As Lieutenant Smith leads his depleted force away from the glider, he hears groans from the smashed fuselage. Among the men lying concussed in the wreckage is Captain Vaughan.

Lieutenant Smith does not charge across the bridge but suffering from an injury to his knee, leads his men at a hobble. On the far side, he encounters one of the men of the German garrison, who throws a stick grenade at him. A fragment hits him in the wrist as he didn’t see him throw the stick grenade. Smith sees the German climbing over the wall to get to the other side. He shoots him, at close range, firing from the hip, as he is going over with quite a lot of rounds. Lance Corporal Madge informs how he is doing and while looking at his wrist he notices that the whole of my wrist is bare.

At the juncture, Lieutenant Smith hears a noise above him. It’s Georges Gondrée, the French Café owner across the bridge, has gotten out of bed and peers over the window ledge. Smith, just having to dela with the German, puts his Sten gun up and fires. The bullet goes over Gondrée’s head, hits the stone roof of his bedroom, and then ricochets down on to the wooden post, into the boards of the bed between them. Gondrée disappears.

Back at glider Horsa No. 3, Captain John Vaughan finds himself lying on the ground in front of the glider with his face in the mud. His corporal is shaking him to wake up. he hears these frightful groans and somehow staggers to his feet outside the glider. He finds a soldier mixed up in the wreckage but can’t get him out to give him a shot of morphia and staggers away. He walks away in the direction of the bridge, which is only about fifty metres away. He gets to the bridge and the first thing he hears is the clatter of the ammunition going off in this tank that has been hit.

Lieutenant David Wood is making his way back to report to Major Howard reporting that he has cleared houses by the bridge. Accompanied by his batman and platoon sergeant, all three are hit by a burst of sub-machine-gun fire. Lieutenant Wood is hit in the left leg and falls to the ground. He shouts and before long his medical orderly, Lance Corporal Harris comes along and very quickly gives him an injection of morphine and splints his leg with a rifle.

Meanwhile, the airborne sappers under Captain Jock Neilson search the bridge for demolition charges. The German engineers had planned to raise the bridge before firing the charges, using the counterweight as a lever to twist and distort the steel girders, making removal and clearance even more difficult. To the amazement of the men from 249th (Airborne) Field Company, Royal Engineers, they find no explosives on the bridge.

The Café Gondrée becomes the Casualty Command Post. The tables are pushed aside in the main room and the soldiers are laid out there. The kitchen is used as a reception area and the dining room as an operating theatre. Here, Captain Vaughan and later the Regimental Medical Officer of 7th Battalion operate at the dinner table. Arlette Gondrée is a trained nurse and helps where she can.

| Ranville bridge over the Orne River |

At the Orne bridge to the east, Horsa No. 5, flown by Staff Sergeant Pearson with Lieutenant “Todd” Sweeney and 23 Platoon, hits an air pocket on its final approach and lands at the far end of the field, 1,200 meters from the objective. Horsa No. 6, flown by Staff Sergeant Roy Howard with Lieutenant Fox and 17 Platoon, lands closer to the bridge. During the final approach, the nose of the glider seems to dip, and Staff Sergeant Howard struggles to keep the trim correct. He shouts, “Mr Fox, Sir! Two men from the front to the back, quickly!” and Lieutenant Fox orders two soldiers to move to the rear and adjust the loading.

As the glider descends, Staff Sergeant Howard sees LZ-Y below him. ‘We were now at 365 meters and there below us the canal and river lay like silver, instantly recognisable. Orchards and woods lay as darker patches on a dark and foreign soil. Howard is aware where they are, it all looked so exactly like the sand table that he had a strange feeling that he had been there before.

During the smooth landing, the wheels came off, The Horsa skidded on its tummy for a long way and came to a standstill just like that. They were thinking we should be riddled with bullets. I tried to open the door but it was all quiet. Lieutenant Fox couldn’t open the door. He pulls and pulls at the door but stays in place. Fortunately, Sergeant Thornton comes up from the back and tells him to just pull it forward. It then just slid up and the men jumped out. Tommy Clare, who jumped out behind the Lieutenant, has his Sten on automatic fire, not on the safety, so when he lands his Sten hit the ground and shot a burst of fire straight into the air. As everybody thinks they are being fired at, they make this arrow formation under the wing they have practised and sit in absolute silence.’

With Sweeney’s platoon behind them, it is up to Fox to capture the bridge and they storm forward. The machine gunner on the far bank opens inaccurate fire. Sergeant Thornton puts a 51 millimetres mortar grenade on the position. Meanwhile the rest of the platoon all go across yelling “Fox! Fox! Fox!”. Sergeant “Wagger” Thornton ready setting up the 51 millimetres mortar, fires two high-explosive grenades that explode either side of the bridge at the eastern end. This is sufficient to send the machine-gun crew scurrying into the dark, followed by a burst of fire from their abandoned gun, now under new ownership. Soon after they secure the bridge, Sweeney and 23 Platoon arrive. As they pass Horsa No. 6, it appears like a riverside summerhouse in the dark. When they arrive at the bridge shouting their identifying code word ‘Dog! Dog! Dog!’. As Lieutenant Sweeney turns up and says “What’s happening, Fox?” Fox replies, “The exercise went very well, but I can’t find no bloody umpires to find out who’s killed and who’s alive!”

Within a few minutes, a message is received on Corporal Tappenden’s wireless from Lieutenant Fox and Lieutenant Sweeney at the river bridge. They report that they have captured it without any opposition but that there is no sign of the third glider containing Brian Priday and Hooper’s platoon. They note that the enemy has run off, leaving their guns in weapon-pits, still warm from the sentries’ occupancy. The news that the river bridge is secure is a relief for Major Howard, and he instructs Tappenden to send out the success signal for both bridges being captured intact.

War Substantive Lieutenant Bence and his Sappers onboard Horsa No. 6 search the bridge, cut all wires, and found the chambers ready to receive their charges of explosive, but no charges have been laid. These are later found in a magazine near the canal bridge. It is just ten minutes after they had landed. Corporal Tappenden begins sending out the success signal, “Ham” for the canal bridge and “Jam” for the river bridge. They hope this message will be picked up by Brigadier Poett, who has a wireless set on their net, having dropped with a special stick of Pathfinder Paratroopers ahead of the main force at about the same time they landed.

Tappenden continues to send out this message with monotonous regularity positioned alongside Major Howard, who well remembers his voice repeating over and over again, “Hello Four-Dog, Hello Four-Dog, Ham and Jam, Ham and Jam.” Major Howard is certain he eventually hears Tappenden say, “Ham and Bloody Jam!”

| The missing glider |

Captain Priday’s glider, No. 4, carrying 22 Platoon under Lieutenant Hooper’s command, along with five sappers, Captain Priday’s runner, and himself. The flight towards their objective is tense, and smoking is allowed to calm the nerves of the troops. At 23:50, thirty minutes before their scheduled landing, Captain Priday orders the lights out to avoid detection by enemy fighters, and they check their equipment and weapons. He worries silently about the grenades’ safety during landing but refrains from voicing his concerns.

At approximately 00:05 on June 6th, 1944, Captain Priday orders safety belts to be fastened and reminds everyone to hold on to one another and lift their legs clear of the floor for the landing. He gives special instructions to Lieutenant Hooper and Private Johnson, seated beside him, to hold him tightly as he needs the door open for a quick exit. They perform their task well. As they descend, Priday keeps a running commentary from the cockpit, but visibility is poor due to the dark, cloudy night.

They successfully cross the French coast, avoiding flak, and begin their descent. The landing is hard due to darkness and poor visibility, causing the glider to bounce and eventually crash with significant force, breaking up the floor and seats. The team exits the wreckage by 00:22, realising they have landed in the wrong place – a bridge near Varaville and Perriers-en-Auge on the River Dives, almost thirteen kilometres from their objective at the Ranville Bridge across the Orne.

Captain Priday quickly assesses the situation and moves the men away from the glider for safety. He sends Lieutenant Hooper to scout the bridge. They find a German helmet but no enemy soldiers. Unable to retrieve any stores or equipment as the Germans manning the small bridge come to their senses and begin firing machine guns into the glider, Captain Priday’s men take cover in a nearby hedgerow. The pilots are distraught at the miscalculation, but Captain Priday reassures them that it wasn’t their fault and praises their excellent landing.

As they prepare, they encounter two enemy sentries. Lieutenant Hooper opens fire, causing the sentries to flee, one being hit. They move to the edge of the road where they encounter a machine gun and stick grenades. Priday and his men return fire with small arms and incendiary grenades, successfully neutralizing the threat. During this exchange, Lance Sergeant Raynor is wounded by a German who fires his weapon as he falls. Priday retrieves essential equipment from the glider, including maps and a signal pistol. They then see paratroopers dropping nearby. They contact a group of parachutists led by Sergeant Lucas, who joins them along with a concussed soldier found later. With maps that Captain Priday has managed to bring and the pilots’ accounts of what they saw while landing, they determine their location: they have landed on the River Dives near Varraville Bridge.

Captain Priday formulates a plan. Realizing they have missed the assault at the canal and Orne bridges, he decides they will first take the nearby bridge from the small enemy force guarding it, then attempt to rejoin the battalion at Ranville. The men succeed in taking the bridge after a short battle in which the enemy guarding it is killed. Afterward, Captain Priday plots their route and sends Lieutenant Hooper and two men ahead to reconnoitre a small wood they need to pass through. The soldiers soon return, giving the ‘all clear’ and reporting that Lieutenant Hooper is waiting in the wood. Suddenly, they hear the sound of boots coming down the roadway and jump for cover in the hedge. Captain Priday hears Lieutenant Hooper’s voice, speaking unnaturally loudly, and realises why when he sees Lieutenant Hooper being prodded along by a German soldier. Lieutenant Hooper contrives to position the German against the skyline, and Captain Priday takes aim with his Sten gun, shouting ‘Jump Tony!’ before firing. Lieutenant Hooper leaps aside, and the German falls dead, but his gun discharges as he falls, injuring Sergeant Titch Rayner and ricocheting off Captain Priday’s map case.

As the group makes their way towards their objective, they encounter flooded fields, swimming and wading for about two hours to move south. They find a farm to rest and dry their clothes. In the morning, the coastal bombardment for the seaborne force’s landing shakes their shelter. The French farmer provides them with milk, which they gratefully drink, having eaten and drunk nothing since landing. Priday scouts for a reported jeep and gun, finding nothing. The farmer’s niece offers to guide them to Robehomme, which is in the direction of Ranville.

Along the way, they are joined by lost Canadian paratroopers and other stranded soldiers, swelling their numbers to around forty-five men. Captain Priday’s group heads for the Bois de Bavent, involving more swimming and wading through flooded areas. Suddenly, they see the unmistakable sight of the Ulsters and their regiment flying in, boosting their morale. Many cheer. Finally, they make it to Ranville via the hamlet of Le Mesnil. It is dark by the time they arrive. Captain Priday reports to his battalion Headquarters, declaring that he and Lieutenant Hooper’s platoon are missing no more. They find the rest of the unit there, having just arrived themselves, and a joyful reunion ensues. The men are allowed a few hours’ rest in a house previously used by the Germans as a bunkhouse, and they find some mattresses for themselves in the nearby chateau to rest for the remaining two hours of the night.

| Hold until Relieved |

Naturally, Major Howard is concerned about the absence of the sixth glider at the river bridge, which contains Brian Priday, Tony Hooper, and his platoon. He hopes they have landed nearby and will turn up soon, but he has other pressing matters on his mind. Sandy Smith reports back with the situation on the other side of the canal bridge, stating that things are going fairly well there, although he suspects that Germans are holed up in some of the houses. Howard orders Smith to coordinate the defence of both his and Brotheridge’s platoons and adds that he will send someone to deal with the Germans. Smith charges back over the bridge after Howard asks if he has seen anything of Doc Vaughan. Smith mentions that he thinks Vaughan might have been injured on landing.

Howard wants to ensure that the casualty command post has been established at the agreed place, a small tree-lined lane between the two bridges. Things seem quiet in the trenches that Wood’s platoon had cleared, and Howard yells across the road to Corporal Godbold, who has taken over Wood’s platoon, asking him to go over the bridge, clear the houses in front of Smith’s platoon, and liaise with Sandy Smith. Godbold does an excellent job of commanding the platoon and carrying out his orders.

Howard then orders Sweeney to remain on the river bridge and directs Fox and his platoon to report to the canal bridge to lend a hand, fearing that enemy counterattacks could not be long in coming. Next, he sends the 7th Parachute Battalion Liaison Officer, Macdonald, to make contact with his Commanding Officer. Lieutenant Macdonald has all the information to pass on, and Major Howard is already scanning the skies for the welcome sight of the paratroopers dropping. He watches Macdonald steal away into the night, and as he does so, two stretcher bearers pass by carrying Lieutenant Brotheridge to the Casualty Command Post.

Meanwhile, the uninjured glider pilots are carrying out essential work, ferrying arms, and ammunition from the gliders to Howard’s command post by the bridge. Howard hears one of them struggling up the bank and goes to assist him, finding himself looking into the face of Jim Wallwork, illuminated by the moonlight, and covered in blood from a bad cut on his head. Wallwork dumps the box of ammunition at Howard’s feet and asks, “What next, sir?” Another pilot is running messages to the forward platoons. They refuse to keep clear of the battle and do stalwart work to aid the troops.

Dennis Fox’s platoon arrives from the river bridge, and Major Howard sends them over the canal bridge to form a fighting patrol beyond the perimeter defences facing west, to detect any enemy reconnaissance parties or stop any enemy forming up to counterattack. Jock Neilson and his sappers, having completed their most vital job of dealing with the explosives on the bridge, are patrolling between the two bridges. Major Howard decides it is safe to leave his command post to visit the forward platoons and assess the situation himself.

Howard finds Lieutenant Smith has done his job well and is in control on the other side of the bridge. However, at Brotheridge’s Platoon Headquarters, all is not well. His platoon sergeant, Ollis, is in great pain, having been injured in the back and ribs on landing. Major Howard sends him off to the Casualty Command Post for treatment and puts his senior corporal, Corporal Caine, in control. This means that out of three original platoons, one is commanded by a platoon commander with his arm in a sling and the other two are commanded by corporals.

He returns to the command post and finds Tappenden still “Ham and Jamming” nearby. Just then, he notices Captain Docter Vaughan wandering about in a dazed condition. Vaughan is covered head to toe in slime and mud and stinks to high heaven. It appears that on landing, he’s been thrown into the pond, received a blow to the head, and is obviously concussed. Major Howard takes him by the shoulder and directs him to the Casualty Command Post. Dr. Vaughan initially heads in the wrong direction, showing signs of confusion. Major Howard intervenes, ensuring Vaughan is correctly directed to the Casualty Command Post, and provides him with a shot of Scotch to help him collect his senses.

Major Howard then allows himself to lean back against the steel panels of the canal bridge, his gun at the ready, ever alert to pick up any signs of the enemy. When Major Howard decides to take a brief rest, the hum of numerous engines growing louder in the distance. He looks up to see the sky teeming with planes approaching from the sea. It’s just 00:50 when flares ignite east and northeast of the canal bridge, marking the drop zones for the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades. Paratroopers begin their descent, their parachutes glowing in the flare light, while German tracer fire shoots up to meet them.

Determined to guide the paratroopers to their target, Howard sends out the Victory-V signal with his pea-whistle. The sound of three dots and a dash carries clearly in the night. The sound causes paratroopers, blown off course during the drop, being able to find their direction.

Brigadier Nigel Poett, commander of the 5th Parachute Brigade, arrives quietly and inquires about the situation. Howard provides a detailed update, learning that Poett has lost several paratroopers, and he has lost his communications due to fact that his wireless operator is being killed in Ranville. This explains why Tappenden’s constant signals have received no acknowledgment. Brigadier Poett leaves quickly to join his men after confirming the bridge’s position, his tall figure vanishing into the darkness.

The first signs of a German counterattack come from the village of Bénouville, near Le Port, with the sounds of tanks clanking and firing from Ranville and the river bridge. Lieutenant Sweeney’s platoon spots a patrol approaching along the towpath from Caen. They ambush the patrol, resulting in a skirmish where a Bren gun kills all the Germans, but tragically, one of the killed men is an English paratrooper who had been taken prisoner earlier.

Minutes later, Lieutenant Sweeney’s platoon hears a car and motorbike speeding towards the river bridge from Ranville. They engage the German staff car and escort, killing the motorcyclist and stopping the car.

Back at the canal bridge, the sound of approaching tanks grows louder. Lieutenant Fox’s platoon, equipped with a PIAT anti-tank gun, prepares to engage. Sergeant Thornton takes careful aim and destroys the leading tank with a direct hit. The explosion forces the remaining tanks to retreat, mistakenly believing they face a heavily armed force. This successful defence delays the German counterattack, buying crucial time for the coup de main force.

Doc Vaughan, after regaining his composure upon leaving the command post, immediately tends to Lieutenant Wood, who lies close to the trenches with a shattered thigh from a machine-gun bullet. Despite his severe injuries, Wood’s primary concern is for Brotheridge. Arrangements are quickly made to transport Wood on a stretcher to the Casualty Command Post, where Doc Vaughan skillfully patches him up and administers morphine to ease his pain.

The ongoing explosions of the tank serve as a beacon for many members of the 7th Parachute Battalion, who are lost in the Normandy countryside. The plan is for Major Dick Bartlett and his paratroopers to reach the canal bridge shortly after 01:00 hours. However, Bartlett and his men are dropped in the wrong area and do not arrive until two hours later. Lieutenant McDonald, the liaison officer for 7th Parachute Battalion, returns to the canal bridge unsuccessful in his attempts to meet up with any of his men.

| First Reinforcements |

Major Howard grows increasingly anxious about the arrival of the main force of 7th Parachute Battalion and its officers, as stray paratroopers begin to appear at the bridges, unable to find their rendezvous point. At 02:50, Howard receives a message that 7th Parachute Battalion is finally on their way. Shortly afterwards, Major Fraser arrives with some of his company, followed by his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Pine-Coffin, and more men at 03:00.

Despite the delays, the paratroopers immediately engage in action alongside the glider-borne troops once they cross the canal bridge. Lieutenant Colonel Pine-Coffin takes command from Howard, ordering him to form his company as the battalion reserve while 7th Parachute Battalion moves to their designated positions. Major John Howard and his reinforced set up the company command post in a pillbox, which has been cleared of debris from grenade attacks.

At dawn, the seaborne invasion of Normandy starts with an air and Naval bombardment, targeting enemy coastal defences and Caen. The shelling is intense, and some shells land dangerously close to the Allied positions, causing deafening noise and shaking the ground.

Around the same time, the canal bridge area comes under heavy sniper fire from the direction of the chateau, making movement around the canal extremely dangerous. The snipers are believed to be positioned approximately five hundred metres to the southwest, possibly in a hedgerow, on the chateau roof, or in a water-tower. Near the pillbox, soldiers Wally Parr, Billy Gray, Bill Bailey, and Charlie Gardner discover a 5-centimetres anti-tank gun and its ammunition stored in small cellars off the gun pit. Despite the dangerous sniper fire, they figure out how to operate the gun. Wally Parr seeks permission from Major Howard to fire it, which is granted with a warning to be careful with the aim. Private Parr successfully targets a water-tower and the chateau, believing they are being used by snipers. Major Howard intervenes to prevent further firing at the chateau, explaining it is being used as a maternity home during the occupation.

Around 06.00, three Spitfires appear overhead, performing a victory roll after recognising Allied signals on the ground. They drop a package containing English newspapers, boosting the morale of the soldiers. An hour later, a German gunboat slowly moves up the canal from the direction of Ouistreham on the coast and starts to fire its twenty millimetres gun at the Headquarters of the 7th Parachute Battalion near the church in the area known as Le Port. Due to the bridge’s superstructure, Private Parr cannot use the anti-tank gun against the gunboat. Instead, Corporal Godbold’s platoon takes cover on the Bénouville bank of the canal and waits until the gunboat is within range of their PIAT gun. Private Cheesely fires the PIAT gun and scores a direct hit on the gunboat, causing it to become grounded, allowing Godbold’s men to capture the Germans on board. The prisoners are then taken to the Prisoners Of War cage in Ranville, where General Gale has set up his Divisional Headquarters.

| High Visitors |

Shortly after 09.00, Corporal Tappenden receives a message from Lieutenant Sweeney, prompting Major Howard to observe an extraordinary sight. Howard and his men witness General “Windy” Gale, Brigadier Hugh Kindersley, and Brigadier Nigel Poett marching precisely in step down the road between the two bridges, heedless of sniper fire. Despite enemy sniper bullets, Major Howard decides to meet them halfway. As he approaches the three tall figures about 230 metres from the bridge, he salutes them smartly. General Gale frowns and points out a PIAT anti-tank gun lying on the grass verge, left in the chaos of the previous night, saying, “That shouldn’t be left lying around, Major, could fall into the wrong hands.” The three commanders continue over the canal bridge to the 7th Parachute Battalion Headquarters to confer with Lieutenant Colonel Pine-Coffin.

At about 10:00, the sound of an aircraft is heard above the noise of the ongoing bombardment. A German bomber approaches, diving towards the canal bridge. Everyone jumps for cover and watches helplessly as the aircraft drops a bomb with fatal accuracy onto the bridge. It hits the side of the bridge’s tower with a dull clang and then, unbelievably, drops into the canal with a splash. They brace for the inevitable explosion but are amazed when it fails to explode. “My God,” Major Howard says to Corporal Tappenden in the pillbox, “It was a dud!”

Immediately, two enemy frogmen sent up the canal from Caen arrive, but they are quickly dispatched by the group on the canal banks. Throughout the morning and into the early afternoon, the enemy continues to counter-attack the soldiers at the bridges. The 7th Parachute Battalion, under Major Nigel Taylor, fights bravely in Le Port and Bénouville. One of Major Howard’s platoons is ordered to assist them, and their street fighting training proves invaluable.

By noon, Colonel Hans von Luck receives orders to counter-attack with his 125. Panzer Regiment of the 21. Panzer Division from Caen. However, it is too late. Their positions are quickly spotted by the Allies and come under heavy attack from the sky and offshore warships, significantly weakening their armoured divisions. For those who arrived by glider just after midnight and for the “paraboys,” the day drags on as they struggle to hold off the German tanks and artillery attacks. Many wonder how long they can hold out at the bridges. Major Howard keeps checking his watch, anxious for the arrival of the Commandos meant to relieve them by midday. “Hold until relieved” keeps repeating in his mind.

| Relieved |

Around 13:00 hours, amidst the explosions and gunfire, some of the paratroops and glider-borne troops thought they heard the distinctive sound of bagpipes. Lieutenant Sweeney, nudging Lieutenant Fox as they sheltered together half-asleep, remarked that he could hear bagpipes. Fox responded, “Don’t be stupid, we’re in the middle of France, you can’t have bagpipes.” Similarly, ‘Wagger’ Thornton expressed scepticism, questioning the presence of bagpipes and suggesting it was a crazy idea. Suddenly, through the trees, a piper in a green beret, followed by Lord Lovat, appeared playing the pipes. Private Eric Woods, who was on guard that morning, asked his companion if the Germans played bagpipes, to which he received the reply, “I don’t think so.” Woods then affirmed he thought he could hear bagpipes. A few minutes later, this is confirmed as the sounds of the pipes grew louder with the approach Bill Millin, piper to Lord Lovat, leading the men of No. Commando of the 1st Special Service Brigade up the tow-path along the canal.

The Commandos had landed at Sword Beach and, after a hard fight, pushed inland quickly. Along the way, they are joined by a lone Duplex Drive amphibious Sherman tank from the 13th/18th Hussars, which provides invaluable support. On their way in, the Commandos capture a German horse-drawn transport unit made up of former Soviet Prisoners Of War conscripted into the Wehrmacht. The Russians are happy to surrender, and the carts are quickly loaded with radios, rucksacks, and spare ammunition at the rear.

The first sea-borne troops reach them, greeted by a bugle reply from the 7th Parachute Battalion. Lord Lovat, clad in his trademark Aran wool jumper, strides ahead of his men, with Millin playing, “Blue Bonnets over the Border” on the bagpipes. Despite a fusillade of sniper bullets, Lovat strides straight over the canal bridge alone, ignoring Major Howard’s warnings. The commandos cross the bridge single-file, with several hit by snipers, but their arrival is warmly welcomed by the soldiers holding the bridges. Lovat and Major Howard shake hands, and despite Lovat’s claim of saying, “Today history is being made,” Major Howard only remembers saying, “About bloody time!”