| Page Created |

| November 8th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| December 2nd, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Special Forces |

| 1st Airborne Division The Glider Pilot Regiment |

| Related Operations |

| Operation Mincemeat Operation Turkey Buzzard/Operation Beggar Operation Narcissus Operation Husky Operation Husky, Special Raiding Squadron Operation Husky No. 1 Operation Ladbroke Operation Ladbroke, Coup de Main Operation Husky No. 2 Operation Fustian Operation Chestnut Special Raiding Squadron, Raid on Augusta |

| Related Pages |

| Airspeed Horsa WACO CG-4A |

| Date |

| Operation Ladbroke |

| Objectives |

- Capturing the Ponte Grande Bridge.

- Securing Syracuse harbour.

- Neutralising a coastal artillery battery within range of the amphibious landings.

| Operational Area |

| Allied Forces |

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Airlanding Brigade

- 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment

- 9th Field Company, Royal Engineers

- 1st Parachute Brigade

- 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- 16th (Parachute) Field Ambulance

- 1st Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Artillery

- 1st (Airborne) Divisional Provost, Corps of Military Police

- 1st Airlanding Brigade

- The Glider Pilot Regiment

- No. 2 Wing

| Axis Forces |

- Coastal Troops Command

- 136th (Autonomous) Coastal Regiment, responsible for the coast from the East of Palermo to including Cefalù

- CIII Coastal Battalion

- CDLXV Coastal Battalion

- 202nd Coastal Division, responsible for the coast from Mazara del Vallo to Sciacca

- 207th Coastal Division, in Agrigento, responsible for the coast from Sciacca to Punta Due Rocche to the East of Licata

- 208th Coastal Division, responsible for the coast from Palermo to Trapani

- 230th Coastal Division, responsible for the coast from the South of Trapani to Mazara del Vallo, augmented with units of the 202nd Coastal Division

- XXIX Coastal Brigade – Harbour Defence Command “N”, in Palermo

- 136th (Autonomous) Coastal Regiment, responsible for the coast from the East of Palermo to including Cefalù

| Preperations |

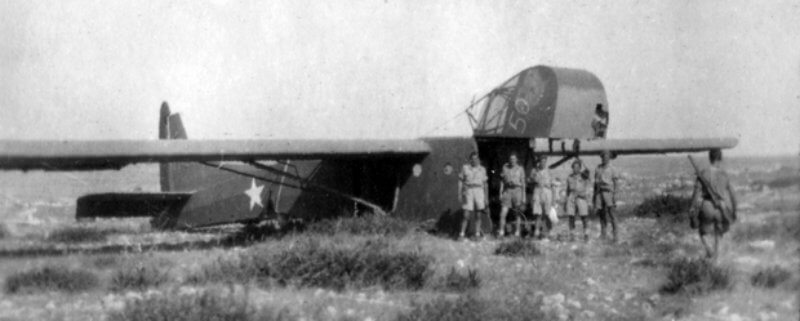

Operation Ladbroke is a glider landing mission undertaken by British airborne troops near Syracuse, Sicily, beginning on July 9th, 1943, as part of Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily during the Second World War. It is the first large-scale Allied glider operation, launched from Tunisia by the British 1st Airlanding Brigade under the command of Brigadier Philip Hicks. The mission involves a force of 136 Waco Hadrian gliders and eight Airspeed Horsa gliders, with the objective of landing near Syracuse to secure the Ponte Grande Bridge and ultimately capture the city, including its strategically important docks, as preparation for the full-scale invasion of Sicily.

By December 1942, with Allied forces advancing through Tunisia, the North African campaign is drawing to a close. As victory in North Africa becomes imminent, discussions among the Allies turn to determining their next objective. Many American commanders advocate for an immediate invasion of Northern France, while the British, as well as General Dwight D. Eisenhower, argue that the island of Sardinia would be a more suitable target. In January 1943, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt meet at the Casablanca Conference and decide that Sicily will be the next Allied target. The invasion is expected to open up key Mediterranean shipping routes and provide airfields closer to mainland Italy and Germany. The codename for this invasion is Operation Husky, and planning commences in February.

Initially, the British Eighth Army, under General Sir Bernard Montgomery, is assigned to land on the southeastern corner of Sicily and advance north towards Syracuse. Two days later, the U.S. Seventh Army, commanded by General George S. Patton, is to land on the western coast and advance towards Palermo. However, in March, the plan is revised to have both armies land simultaneously along a 160-kilometre stretch of coastline to maximise their impact and prevent Axis forces from defeating the Allied armies in turn.

In support of these amphibious landings, Major-General George F. Hopkinson’s British 1st Airborne Division and Major General Matthew Ridgway’s U.S. 82nd Airborne Division are tasked with conducting airborne operations behind enemy lines. General Montgomery revises the plans again in early May, insisting that airborne troops should be landed near Syracuse to secure the valuable port. Consequently, the British 1st Airborne Division’s mission is expanded to include three key objectives: capturing the Ponte Grande Bridge, securing the port of Augusta, and taking the Primasole Bridge over the River Simeto.

The 1st Airlanding Brigade faces additional setbacks due to a shortage of serviceable gliders. In early May, the Waco gliders begin to arrive in North Africa, although they do not arrive ready to fly. Instead, the first batch is neatly packed in wooden crates at La Senia airfield in Oran, Algeria. Not wanting to wait for someone else to begin assembly, six officers and sixty-two Non-Commissioned Officers from the glider regiment move to La Senia on May 8th, 1943, uncrate, and assemble the gliders, using the empty crates for accommodation. Within ten days, and with the help of two American fitters, they assemble fifty-two Wacos, which are then flown to Froha and Thiersville by C-47’s.

An additional 500 Wacos are shipped from the United States at the start of May. As they arrive at various North African ports, the Americans begin assembling them urgently. However, many challenges arise due to the haphazard unloading of the crates, causing parts to be scattered across multiple locations, and vital instruments occasionally missing. Despite these setbacks, by June 13th, 1943, 346 Wacos are completed and delivered to the 51st Wing. However, many are grounded for repairs by June 16th, 1943, and by June 30th, 1943, weaknesses in the wire bracing of the tail units lead to all gliders being grounded for three days. Intercom sets between the gliders and towing aircraft are unavailable until just before the operation begins.

The American 51st Troop Carrier Wing, previously involved in Operation Torch, is now assigned to the 1st Airborne Division for the Sicily invasion. The Wing sets up its operations room at Mascara in May 1943 to coordinate British and American activities. The 51st Wing is part of the American Troop Carrier Command, established in the United States in April 1942 for moving airborne forces.

At Mascara, Royal Air Force representatives from No. 38 Wing, who have flown out to North Africa, attempt to share British airborne experience, but their unsolicited suggestions are often ignored. The situation might have improved with the arrival of Sir Nigel Norman, a charismatic leader whose influence would have been hard to dismiss. However, the No. 38 Wing, Royal Air Force personnel receive the sad news that Sir Nigel has been killed en route.

Despite these difficulties, an intensive three-week training programme is carried out at Froha, where the Glider Regiment’s No. 2 Squadron is based, and at another airstrip in Mascara called Relizane, which becomes the base for No. 3 Squadron. During this period, 1,363 daytime lifts and 510 nighttime lifts are completed.

The 51st Wing’s C-47s are stationed at Thiersville and Matmore, under Colonel R.A. Dunn’s command. The Wing has no previous experience of towing gliders, having focused on paratroop operations during Operation Torch. Throughout the winter since November, its aircraft have been used for transporting men and supplies, owing to the inadequate road and railway systems in North Africa, leaving no time for training in glider-towing operations. Given Churchill’s insistence on an early operation date, only three weeks are available for joint training between the Wing and the airborne troops. This minimal preparation time is recognised as insufficient, but there is no alternative. During the training period, the majority of the Wacos are assembled and maintained by members of the Regiment.

In March, 111 American glider pilots are sent to Relizane and other airstrips to familiarise the British glider pilots with the Waco, which has different landing characteristics compared to British gliders. The Waco is fitted with lift-spoilers instead of flaps, giving it a long, flat glide, making pinpoint landings challenging.

The American pilots, who graduate from flying school only in early 1943, have even less flying experience than their British counterparts. They manage to acquire a few French gliders and tow them with jeeps, but they achieve only short ‘ground hops’. Some of these pilots, originally from the 316th Troop Carrier Group, arrive in North Africa in February 1943 and are quickly assigned as second pilots on C-47s to assist in supplying the British 8th Army. Eventually, twenty-four of them volunteer as co-pilots for the Sicily operation, with nineteen surviving the mission and later being permitted to wear the Regiment’s first pilot wings.

The American pilots request to join the Regiment, but Colonel Chatterton writes back in a letter dated November 2nd, 1943, explaining that while they cannot formally become members of the Glider Pilot Regiment, they are welcome to consider themselves honorary members of the Mess, which is an English tradition allowing honorary affiliation. They are also sent six pairs of wings, and verbal permission to wear them is granted on December 22nd, 1943 by Brigadier-General Paul L. Williams of the US Army.

Some glider pilots from the 316th Troop Carrier Group are sent to Accra in March to assist with assembling the Wacos that have arrived there.

Coordinated planning for the Sicily operation is challenging, as General Alexander’s headquarters, responsible for all ground forces, is based in Algiers, more than 320 kilometres from the American Troop Carrier Command headquarters and training bases. Additional headquarters involved in the planning are scattered from Morocco to Egypt.

In early June, Colonel Chatterton of the Glider Pilot Regiment flies to Malta, from where he is taken over Sicily in a Beaufighter to observe the target area for the operation. Standing between the pilot and navigator, they fly along the Sicilian coast at an altitude of just 15 metres. However, from his awkward observation position, Chatterton cannot discern anything in the darkness that would be helpful in planning the operation, apart from strafing some shipping on their way back to Malta. He returns to North Africa with a growing sense of apprehension regarding the challenging task ahead.

On June 7th, 1943, at 11:30, the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment of the 1st Airlanding Brigade departs Fleurus, Algeria, with transportation provided by the 293rd Transport Company, Royal Army Service Corps. The main contingent arrives in Mascara, Algeria, between 18:30 and 21:00, while a rear party under Captain Wilmot remains behind to oversee remaining duties. One day later, the unit establishes a new camp to the southwest of Froha, Algeria. While the conditions are an improvement, the lack of a reliable water supply poses ongoing difficulties. The rear party from Fleurus reunites with the main unit later in the day. On June 13th, 1943, the battalion begins to receive its transport vehicles in Froha, although some heavy equipment remains unaccounted for.

On June 14th, 1943, the Glider Regiment undertakes its first large-scale exercise in coordination with the 60th and 62nd Groups. Both Groups, newly equipped with their allocation of gliders, participate in Exercise Adam. A total of 54 Waco gliders, each carrying personnel from the 1st Airlanding Brigade, are towed by C-47 aircraft over a distance of 113 kilometres. The gliders land at Froha within a tight 20-minute window on a designated landing zone measuring 915 metres by 275 metres.+

Among the personnel transported are Brigade Headquarters, the majority of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment (excluding A and C Companies), an detachment from 9th Field Company, Royal Engineers, and a medical unit from the 181st (Airlanding) Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps. The operation concludes successfully at 17:44, with all gliders landing as intended, though no vehicles or handcarts are included in the deployment.

By June 18th, 1943, intensive training for the the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment continues in Froha, Alegria as the troops adapt to the harsh North African climate and prepare for upcoming operations.

However, by June 20th, 1943, senior officers from the battalion travel to Thiersville aerodrome, Algeria to observe the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment conducting Exercise Eve. Over seventy Wacos are flown 160 kilometres without incident. The operation highlights logistical issues, including extended landing times and several gliders missing their target airfield.

On June 21st, 1943, a trial night landing by the Glider Pilot Regiment is conducted at Froha at 01:00 using 12 Waco gliders. The exercise, performed without ground illumination, proves largely successful despite minor setbacks, such as one glider failing to take off and another landing incorrectly. Take-off conditions at the North African airstrips are challenging, with thick clouds of red dust obscuring visibility until the gliders and tugs are airborne. Later that morning, at 07:00, orders arrive for the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment to relocate, with a first group of 52 soldiers sent to collect motorcycles for the move.

On June 24th,1943, the Intelligence Officer and two soldiers travel from Froha to Kairouan by C-47 aircraft. They join the advance party at a new encampment 14 kilometres west of Sousse, Tunisia. Three days later, on June 27th, 1943, operational elements of the battalion are airlifted from Sousse to the new location using Waco gliders and C-47 aircraft. However, two gliders fail to arrive as planned. One crashes near Kairouan, Tunisia, resulting in fatalities, while the other lands 400 kilometres off course but without injuries. Untill July 2nd, 1943, the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment establishes itself in an olive grove near Sousse. Training intensifies as the regiment prepares for its role in Operation Husky.

In early July 1943, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment stationed in Kneis, near Msaken, prepares for their role in the upcoming operations. Situated just 13 kilometres southwest of Sousse, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment is allotted a Shut Firing Area in the Arab Quarter of Sousse, now cleared of its residents. Each company is given time for live ammunition exercises, but these drills prove hazardous. Several injuries occur, including four men wounded by splinters from a P.I.A.T. bomb. The most severe incident involves Private Benson of the Reconnaissance Platoon, who loses part of his arm and leg due to the premature explosion of a No. 74 grenade. The firing exercises are halted after stray bullets hit unintended targets in Sousse, injuring a gunner from a coastal defence battery and striking a lighthouse.

By the end of their training period, the members of the Glider Regiment stationed at Mascara have received sufficient practice on Wacos to feel reasonably confident about the upcoming mission. The tug pilots also receive some glider-towing practice, though one significant issue remains unresolved: there is no practice involving landings on landing zones near the coast from offshore releases. This would have been crucial in preparing for the Sicily invasion, as it would have allowed pilots to master the skill of judging distances for offshore releases.

Initially, the American 52nd Wing of the Troop Carrier Command, which had been trained in glider towing in the United States, was meant to be assigned to the 1st Airborne Division for the operation, while the 51st Wing would transport the American 82nd Airborne Division. However, these roles were reversed. By now, the 51st Wing had experience working with the British, while the 52nd Wing had trained with the 82nd Division for three months prior to departing for North Africa, making the switch logical. Additionally, the C-47s of the 51st Wing had been modified for British paratroops during Operation Torch. However, the American 82nd Division’s role in Sicily is limited to paratroops, while the British 1st Airborne Division’s role involves gliders, and the 51st Wing lacks glider towing experience. In the end, the 52nd Wing is tasked with towing the gliders from Mascara to the operational base in Tunisia.

The American C-47s that are to tow the majority of the gliders to Sicily are slow, unarmed, unarmoured, and lack self-sealing tanks. As a result, on the night of July 9th, 1943, glider pilots are instructed to cast off 2,750 metres out at sea to avoid coastal anti-aircraft fire. This requirement, based on the apparent distance from an unfamiliar shoreline, is made more challenging by the lack of prior practice in such releases. The approach to the Landing Zones is also dictated by the vulnerability of the C-47’s to anti-aircraft fire. The route is set northeast along the coastline between Cap Passaro and Cap Murro di Porco to allow tugs to turn out to sea after release, minimising exposure to Syracuse’s anti-aircraft defences.

The 1st Air Landing Brigade’s task, following the night landing on July 9th, 1943, is to capture the Ponte Grande over the Anopo Canal, 1.5 kilometres south of Syracuse, and hold it until relieved by seaborne forces arriving seven hours later. The initial capture of the bridge is to be conducted by two companies of the South Staffordshire Regiment carried in eight Horsa’s, which are to be landed near the bridge. These Horsa’s are to be towed by Halifaxes from No. 295 Squadron, Royal Air Force.

The rest of the Brigade’s troops, carried in Wacos towed by twenty-eight Albemarles from No. 296 Squadron, Royal Air Force and 109 C-47’s flown by Americans, are to release 2,750 metres offshore and land in Landing Zones west of Penisola Della Maddalena. Their objective is to advance to the bridge, secure the position, and, if possible, exploit into Syracuse. The gliders will also carry six 57-millimetres anti-tank guns, ten 3-inch mortars, and seven jeeps. Simultaneously, the Border Regiment is to advance to Syracuse, supported by fifty Wellington bombers. This part of the operation is codenamed Ladbroke, requiring a total of 145 gliders.

Shortly before the operations begin, 145 Wacos carrying 1,200 men of the 1st Air Landing Brigade, along with the ground crews from 296 Squadron, are ferried 917 kilometres from Froha, Thiersville, and Matmore to five airstrips near Sousse and Kairouan on the Tunisian coast. These airstrips are named El Djam Base, El Djam I, El Djam II, Goubrine Base, and Goubrine II. They join forces with nineteen Horsas at Goubrine I that successfully completed Operation Beggar.

Due to the damage suffered by the Halifaxes during the towing operation and the need for essential modifications, only seven Halifaxes are available for Ladbroke. The eighth Horsa, intended for the coup de main party, will be towed by one of the twenty-eight Albemarles from No. 296 Squadron, Royal Air Force, which has also moved to Tunis.

No. 296 Squadron, Royal Air Force, is also involved in ferrying Wacos to the forward area, with twenty-eight lightly loaded Wacos carrying a total of 5,080 kg over six days. The choice of Mascara as the training area, far from the operational base in eastern Tunisia, is intended to preserve operational security, as locating the training closer to the target would indicate Sicily or Italy as the target.

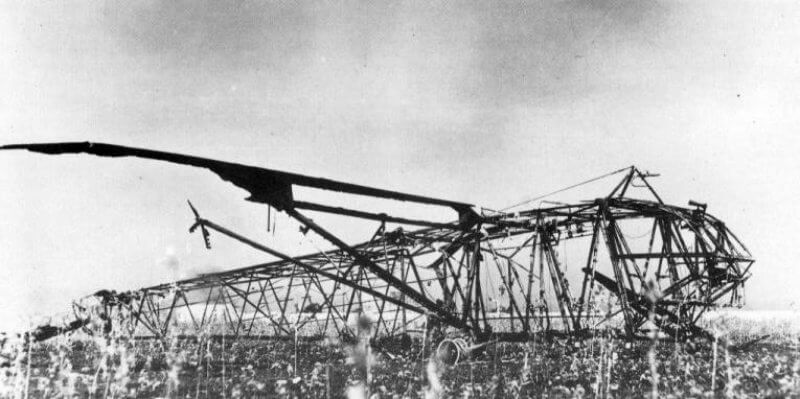

Many of the gliders have not been test-flown, and to compensate, each tug makes a circuit at Froha and other airstrips to allow the glider pilot to assess the airworthiness of their glider. Almost none of the glider pilots have flown continuously for more than an hour, and they are now faced with a challenging mission, including a 2,100-metre crossing of the Atlas Mountains in turbulent air, where drops of 90 to 120 metres are common. Only one fatal crash occurs during the move, caused by a glider’s tail detaching, resulting in the deaths of both glider pilots and all twelve troops aboard. Two other Wacos make forced landings en route.

| Final Preperations |

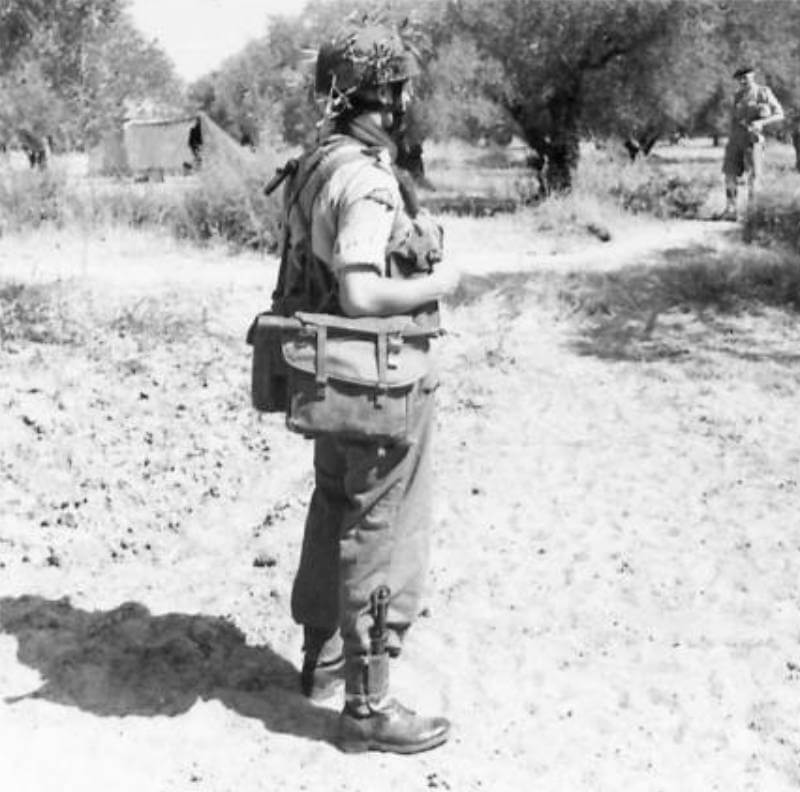

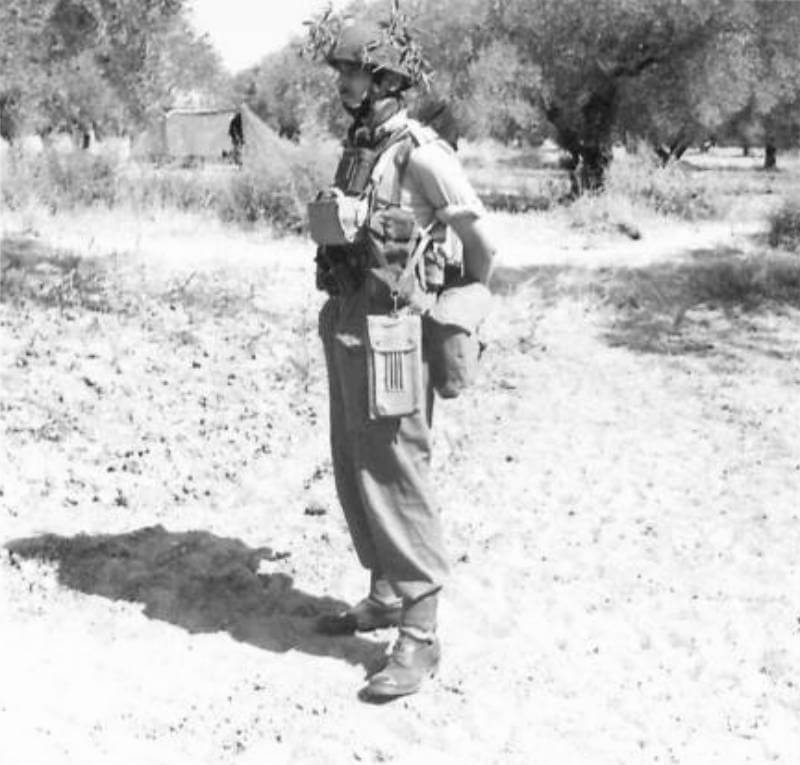

Operation Order No. 1 for both Airlanding Battalion, is signed. From July 3th, 1943 to July 7th, 1943, the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment and the 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment’s officers and troops participate in briefings for Operation Husky. Company commanders receive their instructions on July 3th, 1943, followed by operational officers on July 4th, 1943. Although the North African sun is blisteringly hot, the briefings must be conducted inside for secrecy, as the camps are not protected by the high walls of a barracks but are instead located in open olive groves.

In the days that follow, the men of the 1st Airlanding Brigade, the 181st (Airlanding) Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps and the 9th Field Company, Royal Engineers learn they are to participate in Operation Ladbroke, acting as the vanguard for the entire invasion of Sicily. Their mission is to land ahead of all other forces on the late evening of July 9th, 1943. The 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment is one of two gliderborne battalions in the 1st Air Landing Brigade of the 1st Airborne Division. The 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, are tasked with capturing or destroying any infrastructure that could impede the advance of British seaborne forces along Highway 115 towards Syracuse. The 1st Battalion, Border Regiment, is to land alongside the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment and then advance through their positions to capture the outskirts of Syracuse.

The eight objectives set for the 1st Air Landing Brigade during Operation Ladbroke are codenamed.

- Waterloo is the codename for the Ponte Grande, a triple bridge that serves as the key objective of Operation Ladbroke, carrying Highway 115 and providing a strategic route into Syracuse.

- Putney refers to the railway bridge over the Mammaiabica and Ciane Rivers. It is unclear whether the codename also covers the railway bridge over the Anapo River or any surrounding areas.

- Bilston is a large strongpoint that straddles Highway 115.

- Gnat refers to a gun battery that once defended Syracuse’s harbour.

- Walsall is a strongpoint along Highway 115, located south of the Ponte Grande.

- Mosquito was a battery of guns near Highway 115.

- Dudley and Gornal, A Company of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment is ordered to land in Landing Zone 3 North with the objectives to occupy Dudley, capture Gornal, and establish defensive positions around Putney. It remains unclear where exactly Dudley and Gornal were located, although it is presumed they were near Landing Zone 3 North and Putney. One of them may have been the strongpoint located between the two railway bridges.

The insect codenames refer to Italian gun batteries, which typically include gun emplacements, barracks, and sometimes range finders and fire control bunkers. The Waterloo and Putney bridges in London serve as codenames for bridges over the three waterways south of Syracuse, the Anapo, Mammaiabica, and Ciane Rivers. The remaining names are towns in the Black Country region, north-west of Birmingham. These codenames are used for Italian strongpoints, typically consisting of pillboxes surrounded by barbed wire.

Three landing zones are designated for use by the 1st Airlanding Brigade. Landing Zone 3, divided by both the railway line and the Canal Mammaiabica, lies within 1.6 kilometres of both the Ponte Grande and the railway bridge. A and C Companies of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, along with a detachment of Royal Engineers from the 9th Field Company under their command, are assigned to land here to conduct a coup-de-main raid on the bridges. Their objective is to launch an immediate assault to overwhelm the garrisons, securing the bridges until the main elements of the 1st Airlanding Brigade arrive.

The remainder of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment are to land approximately 3.2 kilometres to the south on the larger Landing Zone 1, while the entirety of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment is to land about 1.6 kilometres east of them at Landing Zone 2. These forces are tasked with marching to the bridges to consolidate the Brigade’s hold, with the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment securing secondary objectives along the way, including two enemy strongpoints and both inland and coastal gun batteries.

Dividing the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, into two task-oriented groups: North Force and South Force, each charged with precise objectives aimed at dismantling enemy defences and securing strategic locations.

North Force comprises A Company and C Company, with attached troops, tasked with seizing and fortifying the key areas of Waterloo and Putney.

A Company sets its sights on the vital areas of Dudley and Gornal, aiming to secure and fortify them against enemy advances. Once established, they will create a defensive stronghold at Putney and disrupt enemy logistics by blocking major north-south and east-west roads. To support their operations, an ammunition dump will be established near Bridge 118293. The company is equipped with Bangalore torpedoes, rabbit wire, grappling irons, and No. 18 wireless sets to ensure mission success.

C Company is tasked with the capture of Waterloo bridge, a critical objective for maintaining strategic control. They will occupy the high ground 365 metres north of Walsall, establish roadblocks, and patrol factory buildings south of Calshot. If feasible, C Company will proceed to capture Walsall after consolidating their hold on Waterloo. Their operations are supported by flame throwers, Bangalore torpedoes, rabbit wire, and wireless communication equipment.

South Force, consisting of the remainder of the battalion excluding A and C Companies, focuses on neutralising enemy installations and securing additional strategic locations.

D Company, supported by the 9th Field Company Royal Engineers, is charged with destroying the Mosquito coastal battery, a pivotal enemy position. Following this, they will prepare to attack additional gun positions and support operations at Waterloo if necessary. Equipped with handcarts, Bangalore torpedoes, and wireless sets, they are well-prepared for their tasks.

B Company’s primary objective is to secure Bilston by occupying enemy positions and clearing buildings along the route to Walsall. Once consolidated, they will hold Bilston against counterattacks. Should D Company encounter challenges, B Company will step in to destroy Mosquito and assist in neutralising Gnat. Their operations are bolstered by flame throwers, Bangalore torpedoes, and grappling irons.

E Company is responsible for capturing Walsall and clearing enemy-occupied buildings on their advance. Additionally, they are tasked with supporting operations at Waterloo as needed. Folding cycles provide enhanced mobility for their operations.

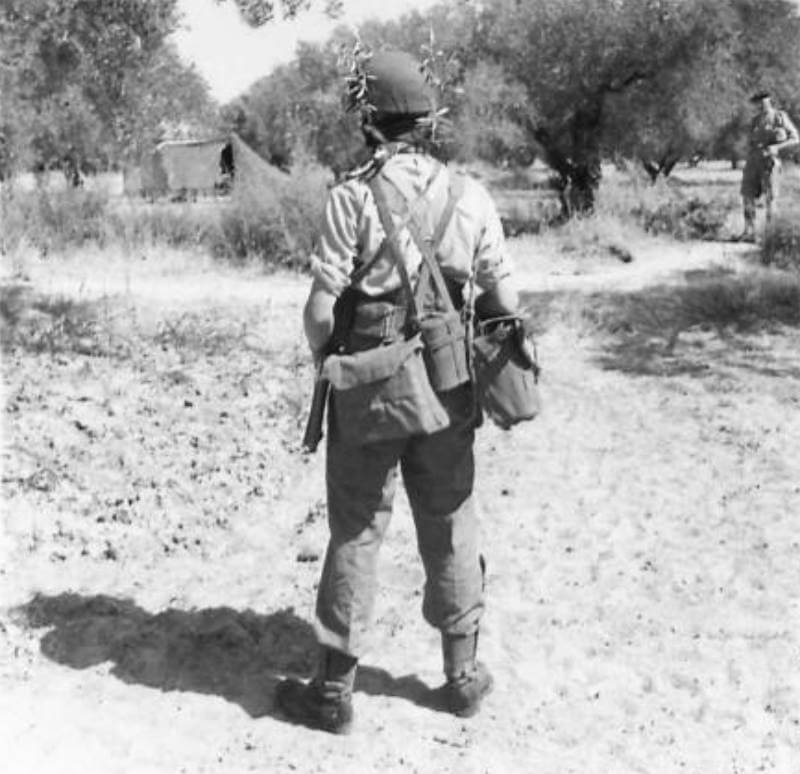

The Pilots from the Glider Pilot Regiment armed with rifles, Sten guns, Bren guns, and grenades, assists in pulling handcarts, seizing high ground near Gnat, and providing logistical and tactical support.

The Mortar Platoon is positioned as a reserve unit, it offers defensive fire and support for coordinated SOS tasks.

The Royal Engineer units are set responsible for clearing minefields, neutralising booby traps, and constructing defensive positions.

The operation is set to commence with gliders landing at designated zones at 22:10 hours. Each company will deplane, form up, and proceed to their respective rendezvous points within 25 minutes. The movement order prioritises B Company, followed by the Glider Pilot Regiment, E Company, and other support units.

Once all objectives are reached, the defence of the bridgehead is entrusted to the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment along with various supporting units attached to the Brigade. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment, supported by one company of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, is to cross the bridge and secure key positions in Syracuse following a bombing raid conducted by Royal Air Force Wellingtons from the No. 205 Bomber Group, Royal Air Force. Following these actions, the entire Brigade is to hold their positions until relieved by British forces advancing from the invasion beaches. This link-up is expected to occur swiftly, with the first troops from the British 5th Infantry Division scheduled to make contact at 07:30 on the morning of the invasion, just nine hours after the first gliders land.

The rapid capture of the port is deemed crucial to the success of the invasion, as its harbour is needed to unload supplies and reinforcements. However, the main seaborne forces of the British 8th Army are not scheduled to land until near dawn, many kilometres south of Syracuse.

The medical teams assigned to Operation Ladbroke prepare for the operation to support the Airlanding Battalions as good as possible. Each Airlanding Battalion Royal Army Medical Corps member, reinforced by additional personnel from the 181st (Airlanding) Field Ambulance, packs their kits with supplies, shell dressings, sulphanilamide powder, scissors, doses of morphine, everything they can fit into their airborne or specialised haversacks. They are tasked with supporting the brigade’s mission, with 24 Royal Army Medical Corps members and one Medical Officer per battalion. Two orderlies are also assigned to each landing area, bringing a mix of anticipation and experience to the mission.

Six Waco gliders are assigned to them, filled with gear and hopes of establishing forward medical care amid enemy territory. A surgical team, led by an officer anaesthetist, is prepared to join the rest of the sections in the operation. A small headquarters unit, composed of the Officer Commanding, the Regimental Sergeant Major, and a Non-Commissioned Officer, travels with the brigade, ready to provide leadership.

As they set off, each section has three gliders, along with wheeled transport, a blitz-buggy (Jeep) for each, handcarts, and an ambulance trailer for one section. Everything is distributed carefully to ensure that each glider load can function independently if necessary. The plan is for each glider to be capable of setting up a Dressing Station or Aid Post on its own if needed.

The surgical team is tasked with conducting immediate forward surgery, beginning at the rear of the battalion area and advancing as needed. Casualties are to be evacuated to Company Collecting Posts, managed by the four Royal Army Medical Corps orderlies stationed there. The Regimental Medical Officer is then responsible for arranging the collection of casualties to the Regimental Aid Post, which is co-located with the Section Dressing Station. The Assistant Director of Medical Services from the 5th Infantry Division manages evacuation to the rear.

| Final days before Operation Ladbroke |

By July 5th, 1943 , the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment faces challenges in securing specialised equipment required for the operation. Despite these obstacles, the atmosphere remains optimistic. One day later, the Commanding Officer delivers an address to all officers and Non-Commsioned Officers, emphasising the critical role of junior leaders in the upcoming mission. Under company arrangements, Other Ranks receive their briefings, displaying enthusiasm and confidence. Meanwhile, the Quartermaster works tirelessly to distribute extra ammunition and equipment.

At Sousse, on July 6th, 1943, a series of explosions occur when the Divisional Ammunition Dump catches fire, causing thousands of tons of explosives to detonate. All hands are mobilised to combat the blaze, but significant losses occur, including ammunition, equipment, and the personal kits of the Glider Pilot Regiment. Several men are injured by flying fragments, but there are no fatalities. The blast destroys tents, small arms, and equipment, prompting frantic efforts to replace everything before the move to the take-off strip on July 7th, 1943. By July 9th, 1943, the Quartermaster’s staff has miraculously managed to restore order.

On July 8th, 1943, General Montgomery visits the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment in Sousse, accompanied by senior officers, including General Browning. His presence inspires the men and raises spirits. That very same day, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment also receives a visit from General Montgomery, commander of the British 8th Army. Addressing all ranks, Montgomery welcomes them to the 8th Army and acknowledges the value of airborne troops, which he notes have been a long-missing component of the force. Later that day, Major T. Haddon, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment’s Second-in-Command, attends a conference at Divisional Headquarters. There, plans for the bombing of “Ladbroke” ahead of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment’s attack are reviewed and finalised without any changes. Throughout the day, gliders at nearby airfields are loaded with supplies in preparation for the operation.

On July 9th, 1943, the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment holds a final church service in Sousse before embarking on their mission. At 15:10, soldiers board transport vehicles for the journey to the airfields, marking the beginning of their active involvement in Operation Husky.

The day of Operation Ladbroke dawns with an unseasonal 48-kilometre-per-hour wind, which causes Colonel Chatterton to revise the cast-off heights for the gliders. Originally calculated for calm air, the Wacos are still to release 2,750 metres offshore, but the height is raised by 90 metres. Gliders bound for Landing Zone 1, mainly towed by C-47’s from the 60th Group, will release at 550 metres, while those bound for Landing Zone 2, towed by the 62nd Group, will release at 425 metres. This decision is made too late to reach many of the combinations before take-off.

The mission’s approach to the Landing Zones, designed to reduce exposure to anti-aircraft fire, takes the aircraft parallel to the coast between Cap Passaro and Cap Murro di Porco, enabling tugs to turn out to sea after release. The objective is to minimise exposure to the heavy flak defending Syracuse.

| Bombing of Syracuse |

The planning for the bombing of Syracuse to support the glider landings of Operation Ladbroke faces significant delays, despite the overall invasion plan for Sicily being nearly six months old. The concept of starting the invasion by deploying airborne troops had been in discussion since January, and the specific plan to land gliders near Syracuse had been in development since May. However, as late as July 9th, 1943, the day of Operation Ladbroke, Lieutenant Colonel Goldsmith, the staff officer responsible for operations for the British 1st Airborne Division, is still unsure about the air support his troops would receive.

Goldsmith first visits the No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, on July 3rd, 1943, just a week before D-Day on July 10th, 1943. As the officer responsible for the operations of the 1st Airborne Division, he is highly concerned about the lack of information, especially as specific target requests had already been submitted by the 1st Airborne Division to Allied Forces Headquarters on May 23rd, 1943, nearly seven weeks earlier. The No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, which consists of several squadrons of Wellington medium bombers, is earmarked by Allied Forces Headquarters to provide bomber support for the 1st Airborne Division. These squadrons are based at airfields around Kairouan in Tunisia, approximately 65 kilometres west of the 1st Airborne Division’s headquarters near M’Saken, Tunisia.

The drive from M’Saken across the flat semi-desert is straightforward, which is fortunate as Goldsmith must make the journey several times. His initial visit on July 3rd, 1943, where he meets Group Captain Simpson, the Senior Air Staff Officer of No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, proves to be unproductive. Despite being cooperative, Simpson has not received instructions from his superiors at Northwest African Strategic Air Force, and the Group has no information on their bombing role. Unsurprisingly, little progress is made.

On July 5th, 1943, Northwest African Strategic Air Force issues a directive listing diversionary targets, including Syracuse, prompting Goldsmith to return to No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, on July 7th, 1943. However, Simpson has still not received specific instructions but promises to attend a conference at the 1st Airborne Division’s headquarters in M’Saken the following day along with his Wing Commanders.

The conference on July 8th, 1943 is reported as “most satisfactory,” but once again, Simpson has still not received any instructions from higher authority. On July 9th, 1943, the day of the invasion, Goldsmith returns, and finally, there is progress. Simpson has been promoted to Air Commodore and Air Officer Commanding and, more importantly, has now received the necessary instructions.

Goldsmith complains that even at this stage, there is still the perception that the Syracuse mission is primarily a diversion to deceive and distract the Italians from the invasion. In reality, the bombing mission has a specific tactical purpose in support of the glider operation. He writes:

“There was still no suggestion that this task had any connection with ground operations, nor was this information given to No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, by Northwest African Strategic Air Force at any later time.”

Simpson, however, advocates for the 1st Airborne Division. Well after midnight on July 9th, 1943, at 01:32, he sends a signal to Northwest African Strategic Air Force informing his superiors of his intentions rather than waiting for instructions:

“As a result of the conference with Divisional Headquarters of the 1st Airborne Division, there is no confusion over our immediate commitments, and any last-minute alterations must be notified to us by the 1st Airborne Division Headquarters. The plan, as arranged between 1st Airborne Division Headquarters and ourselves, is clear-cut, and any alteration will jeopardize the complete Army plan.”

This message effectively states that the entire invasion of Sicily is in jeopardy if Northwest African Strategic Air Force does not comply with 1st Airborne Division’s requests. It is unusual for orders to flow in this direction, from No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, to NASAF, since orders typically flow from Northwest African Strategic Air Force to No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force. Simpson’s assertive message is likely influenced by the urgency and the fact that it is his first day in command.

Northwest African Strategic Air Force responds ten hours later, at 11:17, with an emergency priority message from its commander, Major General Doolittle. Doolittle, renowned as the hero of the 1942 Tokyo bombing raid, denies Simpson’s request for a “maximum effort” on behalf of 1st Airborne Division. Instead, he directs that bombing efforts be spread to four additional towns, thereby reducing the number of planes allocated for the bombing of Syracuse. The decision, to be fair, is influenced by an eleventh-hour directive from General Alexander, the Army commander of the entire invasion.

Doolittle’s response is measured but slightly reprimanding:

“These instructions do not agree with your existing arrangements with 1st Airborne Division. Keep in mind the fact that Wellingtons are required for purposes other than support and diversion for airborne troops. You should conform to the above target instructions in addition to any arrangements made with 1st Airborne Division.”

Doolittle’s words, referring to “support” and “diversion,” reflect the dual nature of No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force’s tasking. The bombing of Syracuse directly supports the advance of the glider troops, while a simultaneous raid on Catania aims to divert Italian attention from Syracuse. The distinction between “support” and “diversion” becomes academic, as the bombing plan for Syracuse remains unchanged.

Tensions between Army and Air Force command are evident, with Goldsmith’s frustrations indicative of the broader mistrust of air support commitment among Army leaders. Army commanders, who believed air forces should be under their control, were frustrated by a lack of air force commitment to support ground operations. The air force, however, prioritised achieving air superiority over Axis forces in Sicily by destroying aircraft and bases, rather than attacking specific ground targets requested by the Army.

The air force’s emphasis on air superiority is understandable—enemy aircraft posed a significant threat to Allied forces, including troopships and infrastructure. Banning enemy planes from the skies seemed more critical than piecemeal ground attacks. Nonetheless, the air force’s lack of clear communication with the Army led to misunderstandings, with Army leaders perceiving evasiveness and obstructionism.

The 1st Airborne Division’s mission in Syracuse evolves into three key phases. In Phase 1, the 2nd Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment, arriving by glider at night, is tasked with capturing the Ponte Grande bridge and securing it for seaborne forces advancing from the beaches further south. In Phase 2, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment, would cross the Ponte Grande bridge to capture the western edge of Syracuse. Finally, in Phase 3, if successful, the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment, would advance before dawn to secure the isthmus connecting old Syracuse (Ortigia) to the new town, taking control of the docks and preventing the Italian garrison on Ortigia from launching counter-attacks.

No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, plays a significant role in supporting these phases. It consists of nine squadrons of Wellington bombers organised into four wings. The bombers provide support through radar jamming, diversionary bombing of Catania, and attacking small towns identified as potential Axis counter-attack points. Additionally, Hurricane fighters are deployed in an “intruder” role, targeting Italian searchlights to protect the glider forces, while Boston bombers drop dummy paratroopers near Catania to distract the enemy.

The most significant bombing support comes in Phases 2 and 3 to support the capture of Syracuse. The commander of 1st Airborne Division, General Hopkinson, actively promotes this mission, viewing it as vital for capturing Syracuse by surprise. He emphasises the need for an intensive bombing campaign to “neutralise” enemy forces, making it easier for glider troops to secure the city with minimal casualties. The narrow 340-metre-wide corridor through which bombs are to be dropped is intended to maximise concentration of bombing, providing “shock and awe” without damaging friendly forces positioned nearby.

Bombing orders for No. 205 Bomb Group, Royal Air Force, specify that Wellingtons must illuminate the target area using flares to ensure accuracy, reducing the risk to friendly forces. Eight Wellingtons are assigned to flare-dropping, providing around 400 flares over 35 minutes to light up the target. The emphasis on precision bombing reflects the critical role this mission plays in the success of the entire invasion.

| On their way |

Loading of the gliders begins at 11:00 on July 9th, 1943, and by 18:40 the men of the two battalions of the 1st Airlanding Brigade are boarding their assigned craft, preparing for take-off. A few minutes later, the first glider-tug combination becomes airborne, and within 90 minutes, all aircraft have left their bases and are assembling into formation.

Problems arise almost immediately during take-off. Seven gliders are lost before the fleet even leaves North Africa; two cast off shortly after leaving the ground, while the rest are forced to return to base due to various issues, ranging from dangerously unbalanced payloads in the gliders to engine malfunctions in the tug aircraft. Later, a Waco glider is inexplicably cast off over North Africa. Believing they are in Sicily, the men set up an ambush along a road in the middle of the desert, far from the terrain they had expected. Eventually, a Jeep from a British mobile bath unit appears, and the men realise their mistake. They are offered a lift back to base.

The loss of these gliders is not unusual, as glider operations are inherently prone to broken tow ropes and other challenges. Without further incidents, the remaining formations reach the rendezvous point several kilometres out to sea, east of Kairouan. However, as they turn towards Malta, they encounter strong winds of up to seventy-two kilometres per hour, making it difficult for the glider and tug pilots to maintain formation.

As the aircraft round the southeastern coast of Malta, a Horsa and two Wacos come down in the sea. One of the Wacos may have been mistakenly released over Malta, with the crew thinking it was Sicily. Onboard are members of A Company Headquarters of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment. Upon disembarking, they hear a Jeep approaching and attempt to persuade the British occupants, assumed to be airborne troops from another unit, to give them a lift to the battalion rendezvous. After a series of refusals and a heated exchange, it becomes apparent that they are, in fact, in Malta, and that their glider is blocking a runway, preventing fighter aircraft from taking off.

The majority of the glider force reaches Malta, but the situation deteriorates as they head north towards Sicily. Strong winds continue to cause difficulties, leading to combinations becoming separated from the formation. The invasion timing is designed to take advantage of moonlight for visual navigation, but gathering cloud cover obscures the moon, making conditions hazardous. The darkness makes it nearly impossible for glider pilots to maintain sight of their tug aircraft, let alone avoid other combinations that occasionally come dangerously close to colliding. In several instances, glider pilots find themselves flying parallel to or even overtaking their tugs, creating a risk of breaking tow ropes or damaging tug engines when realigning and causing a sudden strain on the tow cable.

As the formation approaches Sicily, the sound of aircraft engines draws the attention of Italian anti-aircraft batteries, which open fire. The bright muzzle flashes further complicate the already difficult task for navigators and pilots attempting to identify landmarks. Surviving searchlights from earlier Royal Air Force Hurricane attacks scan the skies, illuminating the aircraft and gliders. The inexperience of some American tug crews becomes evident under fire. The anti-aircraft fire is largely ineffective, causing no damage to any aircraft. However, the noise and flashes create panic among some American crews, leading to confusion. Some aircraft, though far from direct fire, are intimidated and turn back to North Africa with their gliders still in tow. Others release their gliders mid-air, at random altitudes and in any direction, leaving the men inside with little hope of reaching land.

Most aircrews attempt to position their gliders correctly, but the chaotic scene, with aircraft flying in all directions, makes it impossible to maintain formation or navigate accurately. As a result, the 144 gliders, excluding those lost earlier, are scattered, many up to forty-eight kilometres from their intended landing zones. Numerous gliders are released far out to sea, well beyond the planned 3,200 metres. Half of the 1st Airlanding Brigade, comprising seventy-three gliders, ends up ditching in the Mediterranean. Only fifty-six gliders reach Sicily, and of these, just twelve manage to land on or near their designated zones.

Fortunately for those who come down in the sea, the gliders have natural buoyancy in their wings, which in most cases keeps them afloat for several hours before breaking apart. However, the fuselage, where the passengers are seated, sinks beneath the waves almost immediately. The moments following impact are ones of sheer desperation as men frantically attempt to hack their way out before going under. Many do not escape in time; out of the 1,730 men of the 1st Airlanding Brigade, 326 drown. While the majority survive, those stranded far out to sea have no choice but to cling to the wings for up to ten hours, hoping the Royal Navy will locate them by morning.

| Operation Ladbroke, Coup de Main |

The initial wave of six Horsa gliders is scheduled to land at the bridge at 23:15 to attempt an immediate capture, followed two hours later by the main force, landing within a five-kilometre radius of the bridge. Prior to the attack, fifty-five Wellington bombers conduct raids on targets around Syracuse, resulting in the death of the Italian naval base commander, Giuseppe Giannotti. To further confuse the defenders, nearly three hundred dummy paratroopers are dropped north of the landing zone.

At the Ponte Grande Bridge, a single Horsa glider lands, carrying a platoon of infantry from the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment. With approximately fifteen men on board, the infantry, led by Lieutenant Whiters, is split into two groups. One group swims across the river, allowing for a coordinated assault from both sides. The Italian guards of the 120° Reggimento Fanteria “Emilia” abandon their posts, and the bridge is captured. The British quickly remove the demolition charges, preparing to hold the bridge until reinforcements arrive. Only four Horsa gliders land within a three-kilometre radius of the bridge, one of which explodes upon landing, killing all on board. By half past six in the morning, the British defenders number only eighty-seven men.

Despite limited reinforcements arriving, only eighty-seven men are present at the bridge by morning. The British defenders face repeated counterattacks by Italian forces, who bring reinforcements throughout the day. The first Italian counterattacks begin at around ten in the morning, launched by the 385th Coastal Battalion and a battalion from the 75th Infantry Regiment. Initially, the defenders manage to repel several attacks using their limited ammunition and hold their position against overwhelming odds. The Italians launch mortar and artillery bombardments to weaken the British position, followed by infantry assaults. The British troops dig in and take up defensive positions on both sides of the bridge, using what little cover they can find.

The fighting becomes increasingly desperate as Italian forces continue their efforts to recapture the bridge. The British defenders, outnumbered and low on supplies, use captured Italian weapons and ammunition to hold off the attacks. At one point, the defenders resort to hand-to-hand combat as Italian troops attempt to overrun their positions. Despite their exhaustion, the British troops continue to fight tenaciously, determined to hold the bridge until reinforcements arrive.

By midday, the British are nearly out of ammunition, and their numbers have dwindled due to casualties. Only fifteen soldiers remain unwounded, and they are forced to make a final stand. Italian forces, now reinforced with additional troops and artillery, launch a coordinated assault from multiple directions. By half past three in the afternoon, the British defenders, with no remaining ammunition, are overwhelmed and forced to surrender. However, their efforts have delayed the Italians long enough to prevent the destruction of the bridge, as the earlier removal of explosives by the British troops ensures its survival.

Just an hour after the Italians retake the bridge, the first units of the British 5th Infantry Division, which had landed that morning, arrive at the site. For the second time, the bridge falls into British hands intact, and this time it remains so permanently.

| 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment |

The first glider of Battalion Headquarters of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel McCardie, Captain Connellan, and Lieutenant Roberts, crashes into the sea roughly 3.2 kilometers from the shore. As the glider plunges into the cold waters, chaos ensues. Amidst the struggle, two men are lost to the depths. Determined to press on, McCardie and Major Murray, the senior glider pilot, swim to shore under fire. Battling exhaustion and evading enemy patrols, they reach Ponte Grande, where the British forces hold their ground. Meanwhile, the remaining survivors are rescued by naval craft and transported to Suez.

In the second glider, Major Brennan, Captain Miller, and Lieutenant Austin face their own grim fate. Their aircraft crashes only 230 meters offshore, but danger lurks even closer. Machine-gun fire rains down on the team, striking Lieutenant Austin fatally as he attempts to escape. The surviving members, including Brennan, Miller, and two glider pilots, lieutenants Impey and Robson, swim ashore. Undeterred, they begin a grueling journey inland. Crawling through six meters of barbed wire under the watchful eye of a pillbox, they push forward. Over 16 kilometers of hostile terrain, they regroup with three men from an anti-tank detachment and six soldiers from E Company. Along the way, they overpower two pillboxes, capturing 21 enemy soldiers, three machine guns, and an anti-tank gun. Their arrival at Ponte Grande by evening is bittersweet as Lieutenant Impey succumbs to a self-inflicted accidental gunshot wound, a tragic end to his valorous efforts.

The third glider lands amidst a hostile environment at Cape Murro di Porco. Major Hargroves, commander of S Company, and Captain Reverend A.A. Buchanan find themselves surrounded by enemy machine-gun posts. Despite their efforts, they are captured. Their ordeal is cut short when SAS forces intervene, liberating them on 10 July. By the following day, they rejoin the Battalion, their spirits undeterred by the harrowing experience.

The fourth and last glider of Battalion Headquarters meets the most tragic end, crashing into the sea 6.4 kilometers from land. Lieutenant Warneford and two other soldiers are lost to the unforgiving waters. Lieutenant Ashburnham and the remaining survivors cling to life until they are rescued by naval vessels and brought safely to Malta.

Major R.H. Cain commands B Company, 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, which is transported in ten WACO CG-4A gliders with the objective of securing a strongpoint approximately 3.2 kilometers south of Ponte Grande (Waterloo). Seven of the gliders successfully land, but the mission unfolds with numerous challenges and acts of bravery.

Captain Foot, the second-in-command, organises an assault on the company’s objective (Bilston) with half of No. 12 Platoon, led by Sergeant Bradley, and a group from the Border Regiment. Despite their efforts, the position proves too heavily defended, and the attack fails. The group becomes separated, but the following morning, Captain Foot gathers half of No. 11 Platoon and some Royal Engineers he encounters to launch a second assault. This attack also fails against the strong defenses. The group then heads north and attempts to seize E Company’s objective, but this effort is likewise unsuccessful. Eventually, they regroup at Ponte Grande.

Major Cain and half of Company Headquarters crash into the sea and swim to a small island. For 36 hours, they are pinned down by fire from an enemy machine-gun position on the mainland. Finally, they swim ashore, neutralise the machine-gun post, and rejoin the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment.

Lieutenant Goodman, leading half of No. 11 Platoon, crash-lands but pushes toward the company’s objective. Along the way, his group captures two pillboxes. During the action, Lieutenant Goodman is wounded.

Lieutenant Deuchar, with half of No. 12 Platoon, lands on the coast and immediately engages the enemy upon landing. His group makes their way to Ponte Grande, where they play a crucial role in its defense.

Lieutenant Anderson, with half of No. 14 Platoon, crashes into the sea. Tragically, two other ranks drown, but the remainder are rescued by naval craft. The other half of No. 14 Platoon lands on the coast, engages the enemy, kills ten soldiers, and successfully rejoins the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment.

The 3-inch mortar detachment, led by Sergeant Bird, lands safely. They participate in minor skirmishes, during which they eliminate three enemy positions before rejoining the Battalion the following day.

Ten WACO CG-4A gliders are tasked with transporting D Company, 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, on a mission to neutralise a coastal battery along the road between Syracuse and Noto, located 4.8 kilometers south of a key bridge. The battery known as Gnat refers to a gun battery that defends Syracuse’s harbour. Major J.E. Phillp commands the operation, but none of the gliders reach their intended landing zone. Gnat refers to a gun battery that once defended Syracuse’s harbour.

Major Phillp’s glider crashes into the sea. He and half of Company Headquarters swim ashore and rejoin the Battalion at 20:00 on July 10th, 1943. Captain Wright, leading the other half of Company Headquarters, lands on the southeastern tip of the Maddalena Peninsula. After minor skirmishes, his group links up with seaborne forces and rejoins the Battalion on July 11th, 1943.

No. 19 Platoon, under Lieutenant Walters, has both its gliders crash into the sea. The personnel are rescued by naval craft, their mission cut short but lives preserved.

No. 20 Platoon experiences severe losses. Half the platoon, including Lieutenant Brown, crashes into the Gulf of Gela, leaving only two survivors. The other half, led by Sergeant Basten, lands near the intended zone but cannot pinpoint their location. They regroup with the main body the following morning.

No. 21 Platoon suffers fragmentation. Half the platoon, reportedly released near Catania according to the tug pilot, has not been heard from since. The remaining half, under Sergeant Bowditch, crashes into the sea and is rescued by naval craft. Their mission remains incomplete.

No. 22 Platoon, led by Lieutenant Broadbridge, lands approximately 4.8 kilometers north of Portopalo, nearly 90 kilometers west of their intended landing zone. They engage in skirmishes, join the 51st Infantry Division, and return to the Battalion at 17:00 on July 12th, 1943, with their full complement of men, weapons, equipment, and even a handcart.

The 3-inch mortar detachment, led by Sergeant Pateman, lands near Avola. They face minor challenges but eventually rejoin the Battalion.

Major J.A. Neilson commands E Company, 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, a composite unit formed from H Company and the Reconnaissance Platoon. Their mission is to capture a strongpoint approximately 1.6 kilometres south of the bridge. The strongpoint known as Walsall is along Highway 115, located south of the Ponte Grande. The company is transported in seven WACO CG-4A gliders, but the operation encounters significant challenges.

Two gliders carrying Major Neilson and Captain P.A. Davis are reported missing and do not reach the objective. Lieutenant N.E. Pollard’s glider crashes on landing and explodes, resulting in the deaths of Lieutenant Pollard and most of his crew. Sergeant Caulkin’s glider also crashes, leaving him injured. His crew regroups with the main body of the Battalion the following day. Sergeant Charlton and his glider crew are diverted and land at Malta instead of the intended location. Lieutenant Glassborow’s glider crash-lands in an orchard approximately 16 kilometres south of the landing zone. His group marches north overnight, engaging in minor skirmishes. By morning, they encounter strong resistance, are captured, and are later freed by the 17th Infantry Brigade.

H Company, led by Lieutenant Gotto, is made up of two 6-pounder anti-tank gun detachments transported in four WACO CG-4A gliders. The glider carrying Lieutenant Gotto and one of the jeeps fails to take off initially but successfully departs at 20:30 after being reloaded. Following a seven-hour flight, it lands near Ben Gardane in Tripolitania, far from the intended zone.

The second jeep’s glider crashes into tall trees west of the landing zone. The driver is killed, and the two remaining men are injured. The first 6-pounder gun, under Sergeant Howes, lands approximately 13 kilometres south of the landing zone. Without a towing jeep, the gun is abandoned, and the crew joins Major Brennan’s group. The second 6-pounder gun, under Corporal Halliwell, lands in the sea 800 metres from the shore. The surviving crew members swim ashore, are captured, and are freed by the Devonshire Regiment 24 hours later.

Simforce, commanded by Captain Simonds, serves as the Battalion’s Reserve. Two gliders, including Captain Simonds’, crash into the sea, resulting in the loss of eight men. The third glider, led by Lieutenant Reynolds, loses one man to machine-gun fire shortly after landing. That night, Lieutenant Reynolds’ group marches north, links up with elements of B Company, and moves to Waterloo, the Ponta Grande Bridge, to assist in its defence.

| 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment |

Waco CG-4A Glider No.57 departs from Strip C at 19:15 hours, circling for approximately twenty minutes to form up with the rest of the gliders. Once in formation, the flight heads out to sea. Before departure, all personnel receive instructions on actions to take in the event of a water landing, a successful landing at the designated zone, or a crash landing off-course. The glider carries Battalion Headquarters, 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment, personnel, including Lieutenant Colonel Britten, Captain N.A.H. Stafford, Captain G.G. Black, Lieutenant J.S.D. Hardy, Sergeant Burton, Lance Corporal Toman, Lance Corporal Smith, Private Clark, Private Ditte, Private Cull, Corporal Day, and Sergeant Gilbert. The two pilots are Lieutenant Loughran and an American pilot.

The flight is uneventful, and despite a heavy load, including a handcart, five folding cycles, and two No.18 radio sets, the glider performs well. Only two islands, presumed to be Linosa and Malta, are sighted until around 20:00 hours when the Sicilian coast becomes visible to port. Sporadic anti-aircraft fire is encountered but poses no threat.

At what the crew believes is the correct release point, the tug disengages, unwilling to proceed further without evasive action. The glider is cast off at a height of 400 metres, still far from the coast. The glider descends along the south coast of Cap du Porco, aiming for the landing zone but ultimately failing to reach the shore. Lieutenant Loughran issues a “prepare to ditch” order, which is not heard at the rear of the glider. The front emergency doors are jettisoned, but the rear doors remain locked as the glider hits the water.

The fuselage floods immediately, yet there is no panic. Half the crew exits through the doors, while the remainder escape through the roof, which is split open by the first man out. This quick action saves lives. The crew regroups on the wings, shaken but unharmed, only to come under machine-gun fire from enemy positions on the cliffs. Illumination flares launched by the enemy do little to improve their aim. With only three revolvers and 18 rounds of ammunition between them, the crew splits into small groups to attempt reaching the shore, prioritising armed individuals to confront the enemy posts. Upon reaching land, they find themselves at the base of a cliff, unable to scale it to engage the enemy effectively. They decide to remain hidden until morning.

At 02:20 hours on 10 July, a bomber struck by anti-aircraft fire jettisons its payload into the sea nearby before crashing. Captain Stafford sustains wounds to his neck and hand in the explosion. At first light, the crew climbs to a higher ledge along the cliff, locating all but three members of their party. A successful retrieval mission to the gliders yields water, tinned food, and first aid supplies, improving their situation despite the lack of weapons.

At 10:00 hours, Lieutenant Colonel Britten decides to attempt a breakthrough to the Battalion area, roughly 10 kilometres away. He and Lieutenant Hardy set off at 14:00 hours, hoping to reach their destination by dawn. Progress is slow, covering 900 metres in the first two hours due to the rocky terrain. They decide to pocket their revolvers and proceed boldly. At 17:00 hours, they encounter Lieutenant Green, who is escorting 30-40 prisoners but has no detailed information on the Battalion’s position. After refilling water bottles and having tea, they continue onward.

En route, they come across a group of around 60 Italians, both soldiers and civilians. The armed soldiers surrender after being convinced the war is over. Their weapons are destroyed before Lieutenant Colonel Britten and Lieutenant Hardy move on, receiving a cheer from the group as they leave.

As night falls, they are stopped by two Glider Pilot Regiment personnel accompanying a platoon of the South Staffordshire Regiment. Sharing a similar destination, the groups join forces and proceed to Waterloo. Their remaining journey is uneventful, and they report to Brigade Headquarters at 20:00 hours. Exhausted and with tender feet, they take boots from prisoners to ease their discomfort.

By 21:00 hours, they reach the Battalion area and rest overnight. The Battalion moves into Syracuse at 08:00 hours the following day. Parties are sent out to recover the wounded and arm unarmed personnel using enemy weapons. Captain Stafford is evacuated to a Casualty Clearing Station on George Beach at 10:00 hours on July 11th, 1943. The remaining personnel travel to the Battalion area on bicycles, bringing as much equipment as they can salvage from the gliders, using an old Italian car to assist with transport.

On the evening of July 9th 1943, Glider No. 75 boards its personnel at 18:00 hours and takes off at 19:00 hours. After approximately two and a half hours of flight, Malta is sighted at around 21:30 hours. The glider pilot estimates the landing time to be around 22:30 hours. Several men suffer from severe airsickness, but the mission continues as planned. At approximately 22:20 hours, the designated landing mark is spotted. The glider casts off and proceeds toward the objective, appearing to be on course. However, instead of reaching land, the glider lands in the sea, creating a significant setback.

Upon exiting the glider, the men are accounted for, with two identified as non-swimmers. The personnel are organised into small groups of three, pairing each non-swimmer with two capable swimmers. Bearings and landmarks are established to guide the swim towards the coastline, which is estimated to be approximately 4 kilometres away.

As the group swims towards the shore, they come under fire at a distance of about 500 metres from the coastline. A searchlight beam illuminates the area, increasing the difficulty of evading the enemy. Some members of the group decide to drift along the coast toward a nearby town. After drifting approximately 550 metres, they make for the shore and successfully climb the rocky coastline.

At the top, the group encounters multiple obstacles, including barbed wire consisting of three double rows of Dannert wire and three single apron fences. The men navigate through these defences and discover three enemy gun posts equipped with what appear to be 9.2-inch guns supported by two light machine gun positions.

Despite limited armaments, four No. 77 grenades and two No. 36 grenades, the group acts swiftly. The nearest post, located about 180 metres away, is approached first. Two sentries are neutralised using two No.77 grenades. The enemy retaliates with automatic weapons, forcing the group to crawl into hiding. Shortly thereafter, the remaining gun crew, approximately five Italian soldiers, approaches the position. Two No. 36 grenades are deployed, successfully neutralising the threat. The group remains concealed for the rest of the early morning hours.

By 07:00 hours on July, 10th, 1943, increased activity inland prompts the group to move cautiously in search of other unit members. Contact is finally made with a Royal Engineers Bridging Party, which provides directions to the beach. At the beach, a Brigade Adjutant from the 51st Brigade Headquarters directs the group to Area 86. There, additional unit members are located, who guide the group to Battalion Headquarters.

As WACO CG-4A Glider No. 77 carrying a half a platoon of A Company, 1st Battalion, The Border Regiment, approaches its objective, it encounters heavy anti-aircraft fire, prompting the tug aircraft to veer out to sea. The glider is released further from the intended landing zone than anticipated, resulting in a forced landing in the sea. The pilot, foreseeing the situation, executes a controlled water landing.

Amid initial confusion, order is quickly restored. Equipment is abandoned, and Corporal Edgar creates an escape route by cutting through the roof of the glider. The men exit and position themselves along the wings, staying low to avoid enemy fire from the shore. They remain in this position until approximately midnight, when the pilot advises abandoning the glider.

With an estimated distance of 3 to 5 kilometres from the shoreline, the men prepare to swim. Five non-swimmers are paired with stronger swimmers to ensure their safety. Using a prominent fire on the mainland as a landmark, the group sets out, aiming for a point to the right of the blaze to avoid attracting attention.

During the swim, the group becomes separated in the darkness. By using a star for navigation, Sergeant Davidson reaches the intended point, while other members land further along the shore. Attempts to reorganise the group using a torch prove unsuccessful. Enemy flares illuminate a pillbox on the beach, prompting Davidson to cease signalling in the hope that others will move towards his position.

Other individuals in the water lose their composure and shout for help. This activity attracts enemy attention, leading to one swimmer being captured. Davidson and Private Elliott remain concealed. When the captors pass nearby, the British prisoner inadvertently reveals their position, but the enemy withdraws after an unsuccessful attempt to persuade them to surrender.

After regaining strength, Davidson and Elliott move inland, cutting through layers of barbed wire and advancing cautiously. A reconnaissance of the area reveals a hedgerow that provides cover from potential minefields. However, their movements are met with heavy rifle and machine-gun fire. Pinned down within 20 metres of a well-camouflaged enemy position, they are forced to surrender, reasoning that rescue by Allied forces remains a possibility.

The captors treat the prisoners decently, providing blankets to counteract the cold and wet conditions. Searches confiscate their rations, water bottles, and compasses, but Davidson manages to conceal his map despite multiple inspections. Throughout the morning, other Airborne troops who landed in the sea are also captured and brought to the same location. Among them, Private Eagles is confirmed drowned, while Private Birdsell, who had swum ashore independently, successfully joins other units. Private Lane and the two pilots remain unaccounted for.

Later that day, the prisoners are marched to various strongpoints. Observing the route and recalling details from the map, Davidson estimates they are being moved towards Syracuse. Lance Corporal Stevens retains a button compass, and an escape attempt is planned for the evening. However, the position comes under accurate Allied mortar fire before the plan can be enacted.

Capitalising on the confusion, the prisoners engage in psychological tactics, convincing their captors that Allied forces have encircled the island. This leads to many Italians surrendering or waving white flags. When British troops arrive, Davidson is placed in charge of escorting prisoners to the docks. Private Marriott assumes responsibility for transporting wounded using horses and wagons and later assists in gathering prisoners under fire, earning commendation from an officer at the hospital.

On returning, Davidson meets Colonel Jones and joins his group en route to Syracuse. They take up positions south of Waterloo on high ground, where they reunite with the rest of the Battalion. A final check reveals Private Eagles drowned, Private Lane and the two pilots missing, and Private Birdsell fighting alongside the South Staffordshire Regiment before rejoining the Battalion.

The conduct of the men, particularly Privates Elliott and Marriott, is noted for their exceptional bravery and assistance despite their inability to swim.

| Medical Teams |

When the operation begins, things do not go as planned. Of the six medical gliders that depart, only one successfully lands on the island. This glider carries the surgical team, led by Captain Rigby Jones, and four members of Section 2. They move quickly, establishing a basic Dressing Station combined with a Regimental Aid Post and working tirelessly to assist the wounded. Eventually, they join a Main Dressing Station to work as a surgical team.

Meanwhile, medical orderlies who land with the companies or swim ashore find themselves scattered across the battlefield. Despite being separated from their teams, these men work tirelessly, providing first aid wherever they are needed, fully justifying their inclusion in the mission with their quick and selfless actions.

The failure of most of the medical services to arrive is a heavy blow, but those who manage to land begin operating within an hour. The decision to distribute highly trained medical orderlies widely throughout the battalions proves crucial, as the widespread casualties mean that each isolated group of injured soldiers receives the help they need.

After the landing, it becomes evident that coordination is key. A staff officer from Airborne Forces needs to be attached to the headquarters of the relieving seaborne force, with access to ambulances to ensure swift evacuation of casualties. The chaos of the landing demonstrates the necessity of proper coordination between different forces for effective evacuation.

Despite the setbacks, the medical services that do operate manage to provide efficient care. Every isolated “penny packet” of casualties receives prompt attention, which saves lives.

The larger objective, known as Operation Husky, is for the brigade to capture the Ponte Grande Bridge over the River Napo and Chiane, with a secondary aim of capturing the town of Syracuse. They are also tasked with neutralising enemy strongholds and gun emplacements, landing on four designated landing areas—two smaller ones near Waterloo and two larger ones roughly six kilometres away.

Two orderlies are assigned to each of the larger landing areas, ready to assist as needed. Company Collecting Posts are established in each company area, staffed by Battalion Royal Army Medical Corps personnel, with two additional orderlies assisting with casualty collection. Regimental Aid Posts are set up alongside the Dressing Stations, with the Regimental Medical Officer responsible for collecting casualties from Company Posts.

The surgical team, equipped for essential forward surgery, initially operates near the bridge before moving on to Syracuse. The Senior Medical Officer is stationed at Brigade HQ to supervise the implementation of the medical plan, while the Assistant Director of Medical Services of the 5th Division oversees evacuation behind the Dressing Stations.

The gliders transport the Field Ambulance sections and the surgical team, each loaded to function independently if needed. Blitz-buggies, stretcher trailers, and hand-carts are used to move equipment and evacuate casualties within the brigade area. Each Royal Army Medical Corps member carries a small kit and haversack with essential supplies, while additional equipment is stored in the stretcher trailer, along with comfort supplies, plaster, and plasma. Benzedrine tablets, Mepacrine, and mosquito cream are issued, while each glider carries a blanket and 18 litres of drinking water.

The operation begins on July 9th, 1943, with six gliders departing in the evening for Sicily. The journey is turbulent, and all but one glider end up in the sea. Captain Rigby Jones and his team, landing safely, push to the pre-selected area, setting up a small Dressing Station at a farmstead. They treat over thirty casualties there, working tirelessly through the night and into the next day. It is not until late in the afternoon of D+1 that they can move on from the site.

The battalion Royal Army Medical Corps personnel who land with the companies face challenging circumstances, but their quick action and dispersed presence turn out to be beneficial. They are able to attend to the wounded swiftly, even in isolated pockets.

The Senior Medical Officer reaches the Dressing Station on the evening of D-Day and contacts the Deputy Assistant Director of Medical Services of the 5th Infantry Division. Within hours, arrangements are made for transport for casualties. The Assistant Director of Medical Services Airborne Division had already made contact with the 5th Infantry Division HQ and arranged for civilian ambulances to assist in clearing casualties. These ambulances are used on D+1 and D+2 to ensure that all casualties are moved to safety.

By the end of D+2, all casualties have been cleared into seaborne medical services. On D+3, the air-landing medical services leave the island, with two officers and twelve other ranks of the Field Ambulance embarking for departure.

| Aftermath |

The landing phase results in heavy casualties, with losses difficult to trace. A summary is as follows:

| Departure Location | Landed in Africa | Landed in Malta | Landed in Sea Off Sicily | Landed in Sicily | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waco Gliders | 45 | 1 | 20 | 20 | 3 |

| Horsa Gliders | 8 | – | 1 | 5 | 2 |

Casualties sustained during the initial stages of the operation:

| Category | Killed | Wounded | Missing (Believed Killed) | Missing | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|