| Page Created |

| April 27th, 2025 |

| Last Updated |

| June 4th, 2025 |

| The United States |

|

| Additional Information |

| Unit Order of Battle Commanders Operations Equipment Multimedia Sources Biographies |

| Badge |

|

| Motto |

| – |

| Founded |

| June 13th, 1942 |

| Disbanded |

| September 20th, 1945 |

| Theater of Operations |

| France Italy Germany Austria Switzerland Spain Portugal Norway Poland Yugoslavia Greece Belgium The Netherlands Egyp French North Africa (Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia) Turkey Iran Asia China Burma (Myanmar India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) Thailand Vietnam (then French Indochina) Malaysia Argentina Brazil Mexico |

| Organisational History |

Before the formation of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), American intelligence activities are conducted on an ad hoc basis by various departments of the executive branch, including the State, Treasury, Navy, and War Departments, with no overall direction, coordination, or control. The United States Army and Navy maintained separate code-breaking departments: the Signal Intelligence Service and OP-20-G, respectively. A previous code-breaking operation under the State Department, known as MI-8 and directed by Herbert Yardley, had been shut down in 1929 by Secretary of State Henry Stimson, who deemed it an inappropriate function for the diplomatic arm, famously stating that “gentlemen don’t read each other’s mail.”

At that time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is responsible for domestic security and counter-espionage operations. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt grows increasingly concerned about the deficiencies in American intelligence. On the suggestion of William Stephenson, the senior British intelligence officer in the western hemisphere, Roosevelt requests that William J. Donovan drafts a plan for a centralised intelligence service modelled on the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Donovan envisaged a single agency responsible for foreign intelligence and special operations, including commando raids, disinformation, and guerrilla activities.

During the interbellum, Donovan is convinced that a second major European war is inevitable. His extensive foreign experience and realism earn him the friendship of President Roosevelt, despite their stark differences in domestic policy and the fact that Donovan had harshly criticised Roosevelt’s record as Governor of New York during the 1932 election campaign. Although the two men hail from opposing political parties, their personalities are notably similar. Roosevelt respects Donovan’s experience, feels that Hoover treated him unjustly regarding the Attorney General appointment, and believes that, had Donovan been a Democrat, he might well have become president. Donovan’s national profile has also risen substantially, helped by the 1940 Warner Brothers film The Fighting 69th, in which Pat O’Brien portrays Father Duffy and George Brent portrays Donovan. Recognising an opportunity to harness Donovan’s newfound popularity, Roosevelt begins to exchange notes with him regarding developments abroad, soon realising that Donovan could be a valuable adviser and ally.

Following Germany’s and the Soviet Union’s invasions of Poland in September 1939 and the start of the Second World War in Europe, Roosevelt places the United States increasingly on a war footing. This emerging crisis vindicates Donovan’s earlier warnings, and he seeks a meaningful role within the wartime infrastructure. On the recommendation of Donovan’s friend, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, Roosevelt assigns him a series of increasingly significant responsibilities. In 1940 and 1941, Donovan travels to Britain as an informal emissary to assess the country’s ability to resist German aggression.

During these visits, Donovan meets with key figures in the British war effort, including Prime Minister Winston Churchill and senior directors of Britain’s intelligence services. He also dines with King George VI. Donovan and Churchill quickly form a strong rapport, exchanging war stories and reciting in unison William Motherwell’s nineteenth-century poem The Cavalier’s Song. Churchill, impressed by Donovan’s enthusiasm and commitment, grants him unrestricted access to classified information. Returning to the United States, Donovan feels confident in Britain’s prospects and is inspired by the idea of establishing an American intelligence service modelled on Britain’s example. He strongly urges Roosevelt to provide Churchill with the aid he seeks and, using his legal expertise, assists the President in navigating around the congressional ban on selling armaments to Britain.

British diplomats, who share Churchill’s high regard for Donovan, privately suggest to the State Department that Donovan would make a better U.S. Ambassador to Britain than the then-ambassador, Joseph P. Kennedy, whose defeatism and sympathy for appeasers causes concern. Political columnist Walter Lippmann later observes that Donovan’s findings about Britain’s resilience “almost singlehandedly overcame the unmitigated defeatism which was paralysing Washington.”

Donovan also undertakes an inspection of U.S. naval defences in the Pacific, which he finds severely lacking, and acts as an informal envoy to several Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, encouraging their leaders to resist Nazi influence. Meanwhile, in New York, he maintains frequent contact with British Security Co-ordination chief William Stephenson, known as “Intrepid”, and his Australian-born deputy Dick Ellis, an MI6 officer credited with drafting the blueprint for Donovan’s envisioned American intelligence agency. Donovan and Stephenson, become so close that they are often referred to as “Big Bill” and “Little Bill”.

Dick Ellis is requested to draft a blueprint for an American intelligence agency, the equivalent of British Security Co-ordination and based on these British wartime improvisations. Detailed tables of organisation are disclosed to Washington, among these are the organisational tables that lead to the birth of General William Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services.

In the summer of 1941, Millard Preston Goodfellow is recalled to active duty, now holding the rank of Major in the United States Army. He is reassigned to G-2, the military intelligence section, in Washington, D.C. During his posting at G-2, Goodfellow encounters William Donovan, who shares with him the concept of creating an entirely new civilian organisation responsible for strategic operations. Goodfellow readily endorses the idea, and the two men quickly form a close friendship.

Accounts vary regarding when Goodfellow first meets John Grombach, but it is clear that from their earliest acquaintance, Goodfellow holds him in high regard.

At this juncture, Goodfellow already bears significant responsibility, overseeing the deployment of soldiers and marines to the Far East, North Africa, and Europe in order to monitor and assess the evolving situation concerning the Axis powers.

| Multimedia |

| Office of the Coordinator of Information |

From January 1941 on, Colonel Goodfellow, negotiates with the National Park Service to secure three tracts of land dedicated to training camps for Special Activities/Goodfellow and Special Activities/Bruce. By March, he appoints Garland H. Williams as Training Director. Commander N.G.A. Woolley, loaned by the British Royal Navy, assists Donovan and Goodfellow in organising underwater training and craft landings.

After submitting the “Memorandum of Establishment of Service of Strategic Information,” Donovan was appointed Coordinator of Information on July 11th, 1941, heading the new organisation known as the Office of the Coordinator of Information.

Ellis, described as Donovan’s “right-hand man,” effectively directs the organisation’s development. Ellis liaised daily with Donovan, with future Director of Central Intelligence Allen Welsh Dulles acting as a liaison between Donovan and British Security Coordination at Rockefeller Center.

Despite Donovan’s appointment, his responsibilities carries little real authority, and existing U.S. agencies remained sceptical and even hostile towards British involvement. Until several months after Pearl Harbor, the majority of Office of Strategic Services intelligence originates from British sources. British Security Coordination, directed by Ellis, trains the first Office of Strategic Services agents in Canada, until dedicated training stations are established in the United States, with British Security Coordination instructors providing guidance on tradecraft and the organisation of operations based on Special Operations Executive models. The British also make their short-wave broadcasting capabilities available for American use in Europe, Africa, and the Far East, and supply essential equipment until American production facilities could meet demand.

Colonel Goodfellow assumes a far more active role in shaping Donovan’s brainchild, the Office of the Coordinator of Information. In September 1941, he is officially appointed as the Liaison Officer between Donovan and the G-2 section of military intelligence.

Working closely with Dick Ellis, Donovan establishes the Office of the Coordinator of Information’s New York headquarters in October 1941, located in Room 3603 of the Rockefeller Center. He recruits Allen Dulles to manage the office, strategically situated one floor above the operations of Britain’s MI6.

In that same month, Goodfellow becomes the Director of the newly established Special Activities/Goodfellow (SA/G) branch, taking over the responsibilities previously held by Robert Solberg within the COI. Alongside SA/G, another unit, Special Activities/Bruce (SA/B), is created under the leadership of David K. E. Bruce.

In December 1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States formally enters the war, presenting Goodfellow and Donovan with the opportunity to deploy uniformed soldiers, no longer having to depend solely on covert operations. Goodfellow, Bruce, and Donovan collaborate to establish the first Operational Groups, special warfare guerrilla units, which at this stage remain under the organisational framework of the Office of the Coordinator of Information. They select Camp X, a training facility operated by the British Special Operations Executive, as the site where these early operatives will receive their training.

Donovan also works closely with Charles Howard ‘Dick’ Ellis, an Australian-born British intelligence officer, who has been credited with significantly shaping the blueprint. The blueprint for an American intelligence agency, equivalent to the British Security Coordination and based on British wartime improvisations, is drafted. Detailed organisational tables are submitted to Washington, among them those that ultimately led to the creation of General William Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services.

Ellis is not merely drafting blueprints but was also involved in logistical operations, helping to establish training centres, primarily around Washington. Ellis, effectively runs Donovan’s intelligence service.

In 1942, the Coordinator of Information ceased being a White House operation and is placed under the aegis of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

In January 1942, Goodfellow plays a key role in negotiating with the National Park Service to allocate extensive areas of land for the establishment of three new training camps for members of Special Activities/Goodfellow and Special Activities/Bruce, as well as developing the training curriculum for operators and officers. Primarily, Goodfellow employs a team of War Department inspectors to condemn the properties and then approaches the National Park Service with a proposal: the Office of the Coordinator of Information would lease the land for a nominal fee of one dollar per year, provided they maintain the premises in good order during their occupation.

In February 1942, Goodfellow recruits Garland H. Williams from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics as Director of Training. Williams draws upon his previous experience with the Special Operations Executive at Camp X to model his curriculum.

On February 23rd, 1942, Goodfellow is appointed head of the newly activated Coordinator of Information Service Command, overseeing a staff of 51 officers.

Goodfellow also conceives a mission that would later be known as Detachment 101. The first American unit ever assembled to conduct guerrilla warfare, espionage, and sabotage behind enemy lines, which Donovan formally activates in April 1942.

Acting on a directive from Donovan, Goodfellow is tasked with establishing a communications network for the Coordinator of Information. Goodfellow is longstanding friends with John “Frenchy” Grombach from New York prior to the outbreak of war. Given Grombach’s extensive experience in the radio industry and his intricate understanding of radio station operations, Goodfellow recruits him into the Coordinator of Information to assist in building the network.

Grombach proves indispensable to Goodfellow in the creation of this system. Together, they develop a radio intelligence programme encompassing collection, decryption, and analysis for the Coordinator of Information in Washington. This operation is subsequently expanded to a larger centre in New York. To conceal its true nature, Grombach establishes the Foreign Broadcast Quarterly as a front, while the Coordinator of Information purchases NBC’s Long Island radio station to support the initiative.

However, Donovan soon grows distrustful of Grombach. In one memorandum to Goodfellow, Donovan explicitly states, “…do not use Grombach!” In another, he writes, “I am disturbed by this talk of Grombach… It is clearly not evident to you, but I am told by all sides that he talks too much.”

There is some truth to these concerns, as leaks concerning the Foreign Broadcast Quarterly’s operations within the government emerge. Donovan becomes aware of three particularly troubling issues: Grombach’s unauthorised plans to establish a Black Chamber in New York; his marriage to a woman whom he subsequently appointed as assistant director of the Foreign Broadcast Quarterly without proper security vetting; and his recruitment by Donovan’s rival, General George Strong, along with the State Department, to assist in forming a competing intelligence agency within the Military Intelligence Service, later known as The Pond.

In May 1942, Donovan dismisses Grombach from the Coordinator of Information, an event which fuels Grombach’s enduring animosity and distrust towards Donovan and the Coordinator of Information. Despite this, Goodfellow occasionally continues to use Grombach as an undercover operative throughout the remainder of the war.

Simultaneously, the Foreign Broadcast Quarterly is dismantled. Donovan’s rivals successfully persuade President Roosevelt to order the Coordinator of Information to relinquish control over all communications and propaganda operations, which precipitates the abrupt dissolution of the Coordinator of Information.

By mid-1942, the Office of the Coordinator of Information is structured into several key divisions, each concentrating on different aspects of intelligence and special operations.

Collectively, the divisions of the Coordinator of Information lay the groundwork for the broader activities that will later be expanded under the Office of Strategic Services, significantly shaping American intelligence and special operations during the Second World War. When the Coordinator of Information is established in September 1941, it consists of a modest staff of just 100 personnel. However, within nine months, by June 1942, that number increases to 2,300.

| Office of Strategic Services |

As the U.S. fully engaged in World War II, the need for a more robust and militarized intelligence organisation became apparent. The Office of Strategic Services is formally established by a Presidential military order issued by Roosevelt on June 13th, 1942. At the same time the Coordinator of Information is dissolved. However, the Office of Strategic Services absorbs many of the Coordinator of Information’s functions. Its purpose is to collect and analyse strategic information required by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and to conduct special operations not assigned to other agencies.

Therefor, the Office of Strategic Services is formally placed under the authority of the newly created Joint Chiefs of Staff . However, despite this structural alignment, William J. Donovan, now serving as Director of the Office of Strategic Services, continues to report directly to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This dual arrangement reflects both Donovan’s personal access to the President and the exceptional nature of his organisation.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff, created in February 1942, consists of the senior officers of each of the United States’ armed services. It is designed to improve coordination among the military branches and to facilitate more effective collaboration with their British counterparts. At the urging of Prime Minister Winston Churchill and with the approval of President Roosevelt, the American military planning framework now formally incorporates unconventional warfare, psychological operations, sabotage, and subversion, as essential components of strategic planning. Until this point, such methods have been largely disregarded by the traditional branches of the armed services.

As Donovan’s agency already holds responsibility for such operations, the U.S. Army and the newly constituted Joint Chiefs of Staff recognise the value of placing the Office of War Information within their broader command framework. However, Donovan’s informal and independent style is at odds with the military’s deep-rooted emphasis on hierarchy and discipline. Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower, then head of the War Plans Division, proposes that Donovan be made directly accountable to the Joint Chiefs of Staff to ensure better oversight.

Rather than submit to full military control, Donovan negotiates a compromise. The Office of War Information is placed under the jurisdiction of the Joint Chiefs of Staff but retains its independent organisational structure and avoids being incorporated into Army Intelligence (G-2). This arrangement proves mutually advantageous. Donovan gains access to vital military support and logistical resources, while the armed forces benefit from the capabilities of a specialised agency skilled in intelligence collection, psychological warfare, and covert operations, collectively forming the backbone of America’s unconventional warfare strategy.

Meanwhile, Edgar Hoover is out for Donovan’s scalp and any type of co-operation is pretty well one-sided. Not only Office of Strategic Services, but the British Secret Intelligence, many of whose investigations are bound to lead to America, are constantly being hounded by the Federal Bureau of Investigastions. They are warned by the Department of Justice that Edgar Hoover believes they are penetrating embassies and that he is annoyed is Office of Strategic Services. Although the Office of Strategic Services provides policymakers with intelligence and assessments, it never exercises jurisdiction over all American foreign intelligence activities. The Federal Bureau of Investigastions retains responsibility for intelligence operations in Latin America, and the Army and Navy continues to develop and rely upon their own intelligence sources.

Becoming the Office of War Information, the unit is extensively reorganised. Donovan relinquishes his authority to conduct counter-espionage operations in the Western Hemisphere, a responsibility now transferred to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Additionally, the Foreign Information Service, previously the propaganda arm of Donovan’s earlier agency, the Coordinator of Information, is removed from Office of Strategic Services control. This division, comprising nearly half of the agency’s 2,300 personnel, is absorbed into the newly established Office of War Information, a development which significantly reduces the Office of Strategic Services’s overt propaganda capabilities.

The removal of the Foreign Information Service remains a personal setback for Donovan. He has long regarded the propaganda branch as essential to his vision of psychological warfare. In his view, influencing the morale of both enemy and occupied populations is a critical component of undermining Axis authority and encouraging resistance movements. The unit’s loss to the Office of War Information represents a significant reduction in the Office of War Information’s capacity to shape public perception and inspire rebellion through information warfare.

Nonetheless, Donovan responds to these losses by strengthening the Office of Strategic Services’s focus on secret operations. Activities such as espionage, counter-intelligence, disinformation campaigns, and support for guerrilla warfare now come to the fore. With the formal backing of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the continuing protection of President Roosevelt, the Office of Strategic Services expands in both scale and authority.

In August 1942, Goodfellow formally relinquishes his duties at G-2 and transfers fully to the Office of Strategic Services, finally able to dedicate all his efforts to the new agency and to Special Operations. Until this point, he had been simultaneously serving as Chief of the Contact and Liaison Section of G-2, Director of SA/G, and G-2 liaison to the Office of Strategic Services.

Around this time, with Huntington being appointed as a Director of Special Operations, the original staff under Goodfellow and that under Huntington become embroiled in what official reports describe as a “bitter rivalry.” This division between the two groups persists even after Huntington’s deployment to Europe.

At this stage of the war, the Office of Strategic Services Assessment Unit has not yet been established, and recruitment into the organisation is carried out without regard to future assignments. Goodfellow is a particularly prolific recruiter, although the exact number of individuals he brings into the agency remains unknown.

In December 1942, the issuance of the “Golden Directive” by the Joint Chiefs of Staff fundamentally reorganises the Special Operations Branch. Special Activities/Goodfellow becomes the Special Operations Branch (SO), with the staff being divided between Goodfellow and Lieutenant Colonel Ellery C. Huntington, Jr. Special Activities/Bruce becomes the Secret Intelligence Branch. Goodfellow is subsequently promoted from Director of Special Operations to the position of Assistant Director for the entire Office of Strategic Services, a role he holds for the remainder of the war.

Henceforth, it is no longer authorised to operate within the Western Hemisphere, and the Operational Groups are placed under the direct control of Theatre Commanders whilst deployed. The Operational Groups are separated from the Special Operations Branch and granted independent status within the Office of Strategic Services, forming the newly established Operational Group Command. It is important to note that the abbreviations “OG” and “OGs” refer to two distinct entities: OGs denote the individual Operational Groups, whereas OG refers to their overall command structure.

By 1943, Donovan’s relations with British officials have become increasingly strained, owing to turf wars, strategic and tactical disagreements, stark differences in style and temperament, and divergent visions of the post-war world. British officers disparagingly describe the Office of Strategic Services’s methods as resembling a game of “cowboys and red Indians.” Furthermore, while Britain seeks to preserve its empire, Donovan views imperial structures, at least in certain instances, as obstacles to democracy and economic development.

The Chief of MI6, Stewart Menzies, is particularly hostile to the notion of Office of Strategic Services operations within the British Empire. He firmly forbids the Office of Strategic Services from conducting activities on British soil or from dealing directly with Allied governments-in-exile headquartered in London. Nevertheless, by May 1944, Donovan commands a network of approximately eleven thousand American officers and foreign agents, operating across every major capital in the world.

During the war, Donovan also benefits from intelligence gathered by a clandestine network of Catholic priests across Europe, many of whom engage in espionage activities without the knowledge or sanction of the Pope.

Before the month is out, Donovan is in Italy, overseeing reforms within Office of Strategic Services operations in the Mediterranean theatre. During this visit, he meets with Pope Pius XII to discuss intelligence activities conducted out of the Japanese embassy within the Vatican. In the weeks leading up to the Valkyrie plot against Hitler, Donovan remains informed through Allen Dulles, his representative in Switzerland, who maintains contact with the German conspirators.

One particular success for the Office of Strategic Services is its contribution to the intelligence-gathering effort ahead of the Allied landing on the French Riviera on August 15th, 1944. Thanks to information provided by the Office of Strategic Services, Colonel William Wilson Quinn later notes that the invading forces “knew everything about that beach and where every German was.” Donovan is present for this landing as well, after which he travels to Rome for a secret meeting with Hitler’s envoy to the Vatican, Ernst von Weizsäcker. Shortly thereafter, he meets Marshal Tito to discuss the Office of Strategic Services’s support of operations in Yugoslavia.

In August 1944, Donovan comes into conflict with Winston Churchill over Office of Strategic Services support for Greek anti-royalist factions. As the war in Europe nears its conclusion, Donovan spends much of his time in London, operating from a command centre occupying an entire floor of Claridge’s Hotel. From there, he directs operations across the continent, receiving reports that reveal the Wehrmacht’s disintegration; it is said that he “knew their positions on the battlefield better than German generals did.”

The Office of Strategic Services is structured into several specialised branches, each responsible for distinct aspects of intelligence and operations.

By December 1944, the Office of Strategic Services reaches its zenith, employing approximately 13,000 personnel, of whom around 7,500 are deployed overseas, operating in theatres spanning Europe, North Africa, and the Far East. With the German forces retreating into the heart of Europe towards the end of 1944, the strategic focus begins to shift. Increasingly, Office of Strategic Services resources are redirected to the Far East. The proportion of agency personnel stationed in the China-Burma-India Theatre grows substantially, from 14 per cent in October 1944 to 36 per cent by June 1945, amounting to over 4,000 individuals. This level is maintained until the war concludes in September 1945.

As the Second World War moves towards its conclusion in early 1945, William Donovan turns his attention to the future of the Office of Strategic Services. Determined to secure its survival in peacetime, Donovan begins to advocate for the establishment of a permanent intelligence agency. On February 19th, 1945, the Washington Times-Herald publishes an article revealing Donovan’s proposals, including a confidential memorandum he has submitted to President Roosevelt outlining the creation of such an agency. The article controversially draws comparisons between Donovan’s envisioned service and the Gestapo, fuelling public anxiety about the expansion of government power.

Mindful that the American public demands a significant reduction in the size and scope of federal authority following the war, Roosevelt remains cautious about Donovan’s plan. Nevertheless, Donovan believes he can eventually persuade the President of its strategic necessity. Meanwhile, J. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, vehemently opposes the proposal. Hoover perceives Donovan’s vision as a direct threat to the FBI’s jurisdiction, despite Donovan’s assurances that the agency would be strictly confined to foreign operations and would not interfere with domestic security.

The death of President Roosevelt in April 1945 delivers a severe setback to Donovan’s ambitions. His successor, Harry S. Truman, does not share Roosevelt’s receptiveness to Donovan’s arguments. Although Donovan continues to champion the cause of a permanent intelligence service with determination, his political standing weakens considerably.

By that time, approximately 13,000 personnel are on the Office of Strategic Services rolls. Of these, nearly three-quarters around 9,000, are uniformed members of the armed forces. The majority, some 8,000, belong to the United States Army, including 2,000 officers.

| The end of the War |

While British authorities, along with the United States military and State Department, display relative indifference towards the question of prosecuting war criminals after the war, William Donovan is already lobbying President Roosevelt as early as October 1943 to make preparations for such trials. Roosevelt tasks Donovan with investigating the legal and technical considerations involved, and over the ensuing months, Donovan assembles a substantial body of evidence concerning war criminals. He gathers testimonies and information from a wide variety of sources. Beyond seeking justice, Donovan also wishes to avenge the torture and murder of Office of Strategic Services agents at the hands of the enemy.

When President Truman appoints Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson as Chief United States Counsel for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals, Jackson discovers that the Office of Strategic Services is the only American agency to have made any serious preparation for such proceedings. He subsequently invites Donovan to join the trial staff.

On May 17th, 1945, Donovan travels to Europe to assist in the preparations for the prosecutions. In time, he brings no fewer than 172 Office of Strategic Services officers into Jackson’s team. These officers engage in interviewing survivors from Auschwitz, tracing SS and Gestapo documents, and gathering critical evidence.

Unbeknownst to most observers at the time, Donovan also succeeds in persuading the Americans to block the Soviet Union’s attempt to attribute the Katyn massacre to German forces. Convinced by Fabian von Schlabrendorff, a German opponent of Hitler who is informally attached to his staff, Donovan becomes aware that the Soviet Narodny Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del, rather than the Wehrmacht, is responsible for the mass execution of around 4,000 Polish officers in the Katyn Forest.

It is Donovan who proposes Nuremberg as the location for the trials. He introduces Jackson to important foreign contacts and releases Office of Strategic Services funds to help finance the prosecution effort. Jackson, who had previously been a political rival of Donovan in New York, soon comes to view Donovan as indispensable, describing him as a “godsend.” Acknowledging the vital contribution made by the Office of Strategic Services, Jackson personally lobbies President Truman in an effort to support Donovan’s plan for a permanent post-war intelligence service.

However, tensions soon arise between Donovan and Jackson. In Nuremberg, Donovan personally interrogates many prisoners, including Hermann Göring, with whom he holds ten separate conversations. Yet Donovan grows increasingly critical of Jackson’s strategy, particularly Jackson’s insistence on indicting the entire German High Command regardless of individual culpability, a stance Donovan considers incompatible with American principles of justice. A seasoned prosecutor, Donovan also expresses concerns regarding Jackson’s courtroom methods, finding him inexperienced in building strong cases and conducting examinations. As a result of their disagreements, Jackson removes Donovan from the prosecution team. Donovan returns to the United States.

Despite all the efforts to keep the Office of Strategic Services, the campaign does not succeed. On September 20th, 1945, Truman signs an executive order formally abolishing the Office of Strategic Services.

Over the course of the war, the total number of individuals who serve with the Office of the Coordinator of Information and the Office of Strategic Services at one point or another is estimated to be between 21,600 and 24,000. Women play a vital role in the Office of Strategic Services from its early days. Out of the total individuals who serve in the Office of the Coordinator of Information and the Office of Strategic Services between 1941 and 1945, around 4,000 are women, almost one in four. Most of these women are college-educated and serve within the United States, primarily in Washington, D.C. However, 700 are posted overseas, and a small number operate behind enemy lines.

Those deployed abroad are typically based at major Office of Strategic Services stations in London, Cairo, Naples, Kunming in China, and Kandy, near Colombo in Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). Their responsibilities often mirror the clerical, communications, and language-based duties they perform at headquarters, though their proximity to field operations places them in more immediate contact with military intelligence activity.

| Secret Intelligence Branch |

The men, and some women, of the Secret Intelligence Branche of the Office of Strategic Services are responsible for managing intelligence networks and spy rings composed of indigenous agents operating deep within enemy-held or enemy-occupied territory.

Intelligence collection and analysis rapidly become one of the Office of Strategic Services’s principal functions. The military places particular importance on this intelligence, and within the Office of Strategic Services, it is the Secret Intelligence Branch that becomes the primary source of military-related information.

One of the branch’s earliest and most significant contributions comes in support of Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of Vichy-controlled North Africa in November 1942. In North Africa, a number of Office of Strategic Services agents, including diplomat Robert Murphy, First World War hero and professor William Eddy, and anthropologist Carleton S. Coon, work behind the scenes to reduce the likelihood of armed resistance by colonial Vichy forces. As early as June, while planning is still in its infancy, Amy Elizabeth Thorpe, a thirty-two-year-old socialite operating under the codename “Cynthia,” uses her charm and daring to seduce a Vichy official and gain access to sensitive naval codes at the French Embassy in Washington. There is even some suggestion of Office of Strategic Services involvement in the subsequent assassination of Admiral Jean Darlan, the Vichy French commander.

The Secret Intelligence Branch continues to operate across the Mediterranean, Western Europe, and Central Europe. In the Far East, its networks in China deliver intelligence on bombing targets to the United States Army Air Forces and track Japanese shipping for the United States Navy. Much of this intelligence is gathered via foreign-speaking Americans or native agents, inserted into enemy territory through night-time parachute drops or submarine landings. These operatives gather vital information on enemy military capacity, economic infrastructure, political activity, and the morale of occupied populations.

Among the Office of Strategic Services station chiefs, none is more effective than Allen Dulles, who operates from Bern in neutral Switzerland. A veteran of intelligence work in the First World War and the scion of a prominent family of diplomats and international lawyers, Dulles returns to Switzerland in 1942 and quickly establishes a network of over one hundred informants within Germany. His sources include lawyers, businessmen, trade unionists, and members of the anti-Hitler resistance within the Wehrmacht. Dulles obtains key intelligence on the development sites for Germany’s V-1 and V-2 weapons and receives early insight into the military conspiracies that precede the attempted assassination of Hitler in July 1944.

Perhaps Dulles’ most valuable asset is Fritz Kolbe, a senior civil servant in the German Foreign Office who possesses direct links to the German General Staff. Although rejected by British intelligence, Kolbe is trusted by Dulles, and between 1943 and 1945 he smuggles around 1,600 high-value documents to Bern. These include critical details about the German war effort, foreign relations, and internal morale. The reports generated from Kolbe’s intelligence are regularly passed to President Roosevelt by Donovan himself.

In London, William J. Casey, eventually takes over as Secret Intelligence Chief. A young New York lawyer during the war, Casey receives combat and demolitions training at Office of Strategic Services Training Area B in Catoctin Mountain Park. During the final months of the war in Europe, he oversees the successful infiltration of agents into Germany, an achievement British intelligence had considered impossible.

Despite its successes, the Secret Intelligence Branch is not given access to the war’s most sensitive signals intelligence: intercepted and decrypted Axis communications, code-named Ultra (for German traffic) and Magic (for Japanese). This material remains closely guarded by both American and British military intelligence. However, in 1943, Donovan persuades British authorities to provide some access to Ultra for counter-intelligence purposes, particularly in identifying and neutralising German agents or turning them into double agents.

The Office of Strategic Services Counter-Intelligence Branch, known as X-2, operates under these tight restrictions. Based in London and led by James Murphy, it includes key figures such as James Jesus Angleton, later a controversial leader within the CIA. Angleton completes basic training at Catoctin before undergoing further instruction at SI and X-2 facilities in Maryland and Virginia. X-2 is one of the most secretive Office of Strategic Services units, wielding considerable authority through its access to Ultra. It has the power to cancel ongoing Secret Intelligence or Special Operations missions without providing justification.

While most women in the Office of Strategic Services remain based in Washington and handle clerical and communications duties, a small number of Office of Strategic Services women are trained for roles in Secret Intelligence or Special Operations behind enemy lines. Thirty-eight of them are parachute trained.

| Special Operations Branch |

While the Secret Intelligence Branch of the Office of Strategic Services focuses on gathering intelligence, the Special Operations Branch is established with a different mission entirely, destruction. Its operatives are trained in sabotage tactics, capable of blowing up bridges, cutting railway lines, and leading guerrilla assaults against enemy outposts, logistical hubs, and communications infrastructure. In its early days, however, Special Operations is viewed with scepticism by the United States Army, especially in contrast to the Secret Intelligence Branch, which quickly demonstrates its value during the North African invasion in November 1942. The Army remains unconvinced by the proposed guerrilla and sabotage strategy until Special Operations begins proving its worth in operations across Europe and Asia from 1943 onwards.

Among Special Operations agents, much like in airborne units and ranger battalions, there is a shared ethos of daring and independence. These operatives often exhibit a mix of seriousness and swagger, taking pride in their elite status and readiness to parachute into enemy territory on covert missions, despite the ever-present risk of capture or death. Unlike their SI counterparts, who typically work solo, often as civilians, Special Operations operatives are uniformed military personnel and function in organised teams. SI agents sometimes mock them as “Bang-Bang Boys” for their reliance on explosives and firearms.

An Special Operations team typically consists of an officer paired with a radio operator trained by the Office of Strategic Services Communications Branch. In May 1943, the Office of Strategic Services enhances its operational capabilities by forming the Operational Group Branch. These Operational Groups differ from traditional commandos in that they are recruited primarily for their language skills and cultural knowledge, often drawn from America’s immigrant communities. The intent is to parachute these ethnically linked teams into occupied countries where their linguistic fluency and cultural familiarity would aid collaboration with local resistance forces. By 1944, the Operational Groups include members of Norwegian, French, Italian, Greek, and other nationalities, each group comprising roughly six officers and thirty enlisted men.

The Operational Groups, like the smaller Special Operations teams, are trained for sabotage, hit-and-run raids, and disruption of enemy logistics in cooperation with resistance groups. Their operations are aligned with the directives of Allied theatre commanders and are designed to coincide with major Allied offensives. Office of Strategic Services Special Operations and Operational Group teams are infiltrated ahead of Allied advances into North Africa, Italy, Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Norway, using submarines, small boats, and parachute drops.

In 1944, ahead of the Allied invasions of Normandy and southern France, dozens of Special Operations and Operational Group teams are deployed behind German lines to coordinate with local resistance and conduct sabotage. Among these are the Jedburgh teams, nearly one hundred in number, composed of American, British, and French operatives. These multinational units receive considerable attention after the war. Many American Jedburghs begin their training at Office of Strategic Services Training Area B in Catoctin Mountain Park before continuing their preparation in the United Kingdom. By August 1944, there are around 1,100 Americans serving in Operational Group units across Europe, with total Operational Group personnel estimated at up to 2,000. Meanwhile, some 1,600 Special Operations operatives are also active behind enemy lines.

Most of the American Special Operations and Operational Group personnel undergo their training at Office of Strategic Services Training Area B in Maryland and Area A in Virginia. Their radio operators are trained at Area C, while the Operational Groups receive their initial instruction at Area F, the former Congressional Country Club in Bethesda, before advancing to other sites for field readiness.

The first Special Operations unit to enter combat is Detachment 101, deployed to north-eastern India in mid-1942 to conduct guerrilla warfare against the Japanese in Burma. This initial team of approximately two dozen Americans receives training in the spring of 1942. Half the team, under Colonel Carl F. Eifler, trains at the British Special Operations Executive’s Camp X in Canada, while the other half, led by Lieutenant William R. “Ray” Peers, trains at Catoctin. Operating throughout the Burmese jungle, Detachment 101 recruits and commands nearly 11,000 Kachin and other Burmese tribal fighters. For three years, these guerrillas harass Japanese forces, inflicting considerable damage on the Imperial Army and Air Force.

Later in the war, other Office of Strategic Services Special Operations teams conduct missions in Thailand and French Indochina. Beginning in 1943, Special Operations and SI units also operate in China, providing bombing targets for General Claire Chennault’s “Flying Tigers” and later his bomber squadrons. These units, including newly trained Chinese Operational Groups and guerrillas, sabotage Japanese advances by demolishing railways, bridges, and supply depots. Following the Japanese surrender in 1945, Special Operations rescue teams are airlifted into prisoner-of-war camps to protect Allied captives from possible retaliation by hardline Japanese troops.

Due to the increasing need for seaborne infiltration, demolitions, and sabotage of coastal defences, the Office of Strategic Services establishes a Maritime Unit in June 1943. While early training in waterborne tactics takes place on a lake in Prince William Forest Park, the Maritime Unit sets up a dedicated training facility, Training Area D, in April 1942 on the Potomac River in southern Maryland. Though initially useful, this site suffers from poor conditions: no surf for simulating amphibious landings, freezing winters, and murky waters. The unit subsequently relocates to the Caribbean and California, while Area D remains in use for advanced SO training until its closure in April 1944.

The Maritime Unit pioneers innovations in underwater warfare. It develops limpet mines, collapsible kayaks that can be launched from submarines, and an early model of self-contained underwater breathing apparatus known as the Lambertsen Unit, which allows operatives to swim without leaving a trail of bubbles. The unit also introduces flexible swim fins later adopted by the Navy’s underwater demolition teams. Maritime Unit operatives support and transport Special Operations and Operational Group teams by small craft across the Adriatic to Yugoslavia, across the Aegean to Greece, and across the Bay of Bengal to the coasts of Burma, Thailand, and Malaya. In the Pacific, Office of Strategic Services frogmen assist the U.S. Navy by scouting Japanese-held beaches in advance of Marine landings.

| Morale Operations and Research and Analysis Branches |

After losing the Foreign Information Service, the original propaganda wing of the Coordinator of Information, to the newly formed Office of War Information in spring 1942, William Donovan refocuses his efforts on a more covert form of psychological warfare. He draws a clear distinction between overt propaganda, referred to as “white” propaganda, and covert disinformation, known as “black” propaganda. In January 1943, he establishes the Morale Operations Branch within the Office of Strategic Services. The mission of this branch is to disrupt the morale and cohesion of enemy forces and occupied populations through deceptive, manipulative messaging.

Morale Operations’s strength lies in its capacity to appear authentic from within enemy-held territories. Consequently, its units operate not only from rear-area Allied bases and regional headquarters but also within active war zones, albeit behind Allied lines. These units deploy radio broadcasts and leaflets designed to spread confusion, foster mistrust among enemy ranks, and encourage desertion or surrender. These media products often blend truth with fiction, drawing upon local conditions and recent developments to heighten plausibility.

One of Morale Operations’s most effective initiatives is Operation Sauerkraut, conducted in Italy. A pivotal figure in this operation is Barbara Lauwers, a private in the Women’s Army Corps assigned to an Morale Operations unit in Rome. In the aftermath of the failed assassination attempt against Adolf Hitler in July 1944, Morale Operations propagandists, including Lauwers, capitalise on the internal discord within the German military. They send disillusioned German prisoners of war back behind enemy lines, armed with forged papers and convincing narratives that Germany is on the brink of rebellion. This campaign proves effective, prompting the surrender of hundreds of German soldiers. Later, Lauwers develops another operation which persuades 500 Czech conscripts in the German Army to defect to the Western Allies. For her contributions, she is awarded the Bronze Star Medal.

In the China theatre, Morale Operations efforts are spearheaded by civilian operative Elizabeth McDonald, later known as Elizabeth McIntosh, who arrives in Kunming in early 1945. She reports on the transition from rudimentary printing presses using hand-carved characters to modern lightweight aluminium offset presses developed in Washington. McDonald is assigned to a leaflet campaign providing Chinese and Korean agents with instructions for sabotaging Japanese locomotives using Office of Strategic Services-designed incendiary devices disguised as lumps of coal. When tossed into locomotive fireboxes, these devices explode, severely damaging the engines and disrupting troop transport.

The broader Morale Operations campaign in China is overseen by Gordon Auchincloss, a well-connected socialite and media professional who arrives from the European theatre in August 1944. Under his direction, Morale Operations establishes a powerful radio station broadcasting in various Chinese dialects. These transmissions encourage resistance among the Chinese population and attempt to demoralise Japanese troops through strategically crafted psychological messages.

In parallel with these operations, one of the Office of Strategic Services’s most academically respected and strategically impactful branches is the Research and Analysis Branch. For most of the war, it is directed by Harvard historian William L. Langer and staffed by more than 900 scholars, analysts, and researchers. These individuals draw from extensive resources, including the Library of Congress and overseas archives, to provide deep analyses of economic, political, social, and military conditions in Axis-controlled or contested territories.

The Research and Analysis Branch produces intelligence vital to the planning of Allied operations. For example, its Enemy Objectives Unit in London conducts a thorough study of the German economy and war production systems. It recommends that the Allies focus their bombing campaigns on aircraft manufacturing facilities first, and on oil and synthetic fuel production second. These recommendations are adopted by Allied air commanders and shape the strategic bombing priorities in Europe.

Training for these specialised units reflects the wide range of skills required for modern psychological warfare. Morale Operations operatives, including both men and women, receive instruction at Office of Strategic Services Areas F and E in Maryland. Other officers are trained at Area A in Prince William Forest Park, Virginia. The emphasis is placed not only on leaflet production and broadcasting, but on understanding the cultural and psychological factors that influence both enemy morale and civilian resistance.

| Communications Branch |

William Donovan establishes a centralised Office of Strategic Services Communications Branch on September 22nd, 1942. This branch is tasked with providing secure communications and cryptographic services to support the activities of the Secret Intelligence, Special Operations, and Research and Analysis branches. He appoints Lawrence “Larry” Wise Lowman as chief of the branch. Lowman, formerly vice president in charge of operations at CBS, brings with him fifteen years of experience in radio network operations, an ideal background for the technical demands of covert wartime communication.

The Communications Branch is structured to meet the unique demands of global clandestine warfare. It comprises an engineering section responsible for constructing and maintaining the Office of Strategic Services’s main message centre and regional relay stations, a purchasing and development section tasked with procuring and customising specialised equipment, and a training division responsible for preparing code clerks and radio operators for deployment.

Office of Strategic Services communications agents in the field require not only fluency in foreign languages but also a high degree of independence. As Donovan explains, the autonomous nature of Office of Strategic Services missions demands operatives who can think and act without the direct support typically available to conventional military units.

To meet these requirements, the Communications Branch develops a global wireless and cable communications system. This network connects Office of Strategic Services headquarters to a network of fixed and mobile relay base stations positioned safely behind Allied lines across every major theatre of war. These relay stations serve as intermediaries between headquarters and field agents, whose portable radio equipment has limited range. Field messages are encrypted and transmitted to the nearest base station, which then relays them to Washington and forwards instructions back to agents in the field.

The primary coding method used is the one-time pad, a double-transposition cipher based on random key texts and a memorised Vigenère square. This system is exceptionally secure and, crucially, never compromised during the war.

To support this vast infrastructure, the Communications Branch recruits and trains technical specialists in both communications and cryptography. Radio operators, all of whom are uniformed servicemen, receive their training at Area C in Prince William Forest Park, Virginia. Living in tents and cabins in woodland conditions, these trainees learn to operate and maintain Office of Strategic Services communications equipment, master codes and ciphers, practice direction-finding techniques, and develop fluency in International Morse Code. Cryptographers, including both men and women, are trained in Washington, D.C., though those destined for combat zones also undergo weapons training at Area C.

Between 1942 and 1945, up to 1,500 Communications Branch personnel complete full training courses at Area C, with many other Office of Strategic Services personnel undertaking shorter, specialised programmes in radio and coding.

By the final year of the war, Office of Strategic Services maintains a global communications network operating around the clock. In addition to its Washington headquarters, the Office of Strategic Services Communications Branch runs message centres in roughly 25 key cities across 15 countries. In April 1945 alone, the branch processes 60,500 messages comprising over 5.8 million code groups, a scale of operation that illustrates the vast and vital role the branch plays. Throughout the war, no known breach occurs in the Office of Strategic Services’s secure communications systems.

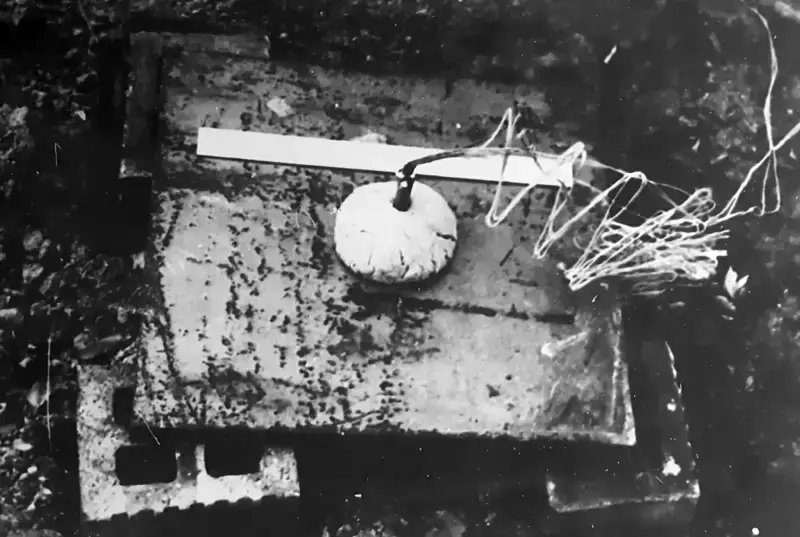

Although most Office of Strategic Services equipment is sourced from the civilian market or the Army Signal Corps, the Communications Branch also maintains a dedicated Research and Development Division. This team designs specialised tools for covert work, including wiretap devices, direction-finding kits, Eureka beacons to mark drop zones, and compact portable radios. One of its most effective innovations is the Strategic Services Transmitter/Receiver No. 1, a suitcase-sized, long-range clandestine wireless telegraphy set. The Office of Strategic Services purchases 8,000 of these sets, which become standard equipment for operatives across Europe and Asia.

Perhaps the most advanced development is the Joan-Eleanor system, deployed in late 1944 in the Netherlands and Germany. This system pioneers the use of Very High Frequency bands, between 200 and 300 MHz, well above the frequencies used by conventional military radios and extremely difficult for the enemy to intercept. Field agents carry a small SSTC-502 radio unit, nicknamed “Joan,” which allows them to speak directly to aircraft circling at altitudes of up to ten kilometres, fitted with a more powerful SSTR-6 unit, nicknamed “Eleanor.” Unlike telegraphy, this system allows for secure voice communication, eliminating the need for time-consuming encoding and decoding.

| Research and Development Branch |

To carry out their clandestine war of sabotage, espionage, and guerrilla action, Office of Strategic Services operatives require a wide array of highly specialised weapons, explosives, and covert devices. These are developed under the direction of the Office of Strategic Services Research and Development Branch, led by Stanley P. Lovell, a chemist and former business executive from Boston. Recruited personally by William Donovan, Lovell approaches his wartime task with scientific precision and imaginative flair, overseeing a series of inventive projects that equip Office of Strategic Services agents with the tools needed to operate effectively behind enemy lines.

Among the specialised weaponry produced are a variety of silenced and flashless firearms. These include pistols and submachine guns engineered to eliminate muzzle flash and sound, ideal for assassinations or operations requiring complete stealth. Operatives are also issued dart guns and even compact, hand-cranked crossbows, designed for silent killing at close range. In hand-to-hand combat scenarios, a selection of knives, blackjacks, and clubs is developed to suit individual mission requirements.

One of the more unconventional weapons adopted by the Office of Strategic Services is the “Liberator” pistol, an inexpensive, single-shot .45 calibre firearm, colloquially known as the “Woolworth gun” due to its cheap production cost of roughly two dollars. Crude but effective, the Liberator is intended for distribution to resistance fighters, particularly in China and the Philippines. Its purpose is brutally simple: the one shot is to be used to kill an enemy soldier and acquire his rifle or sidearm.

For demolition tasks, the Office of Strategic Services adopts and refines several types of explosive materials. Among these is Torpex, a powerful British-developed explosive used in naval mines and depth charges. More prominently, the Office of Strategic Services makes extensive use of Composition C, a mouldable plastic explosive that is both more stable than TNT and more powerful, capable of cutting through a one-inch thick steel plate with devastating efficiency. Composition C becomes the go-to material for sabotage missions involving railway lines, bridges, and armoured vehicles.

In one particularly ingenious development, the Research and Development Branch creates an explosive known as “Aunt Jemima.” This powder, resembling ordinary flour, can be mixed into dough and baked into biscuits without detonating. Though lethal if ingested due to its toxicity, the substance remains inert until activated by a fuse, at which point it becomes powerful enough to destroy structural targets such as bridges or railway junctions. The disguise is intended to allow guerrillas or agents to carry the material past enemy checkpoints without detection.

For the more covert aspects of Office of Strategic Services operations, especially espionage, Lovell’s team designs a wide array of concealed devices. These include miniature 16mm cameras hidden within matchboxes, cigarette cases, or jacket buttons, allowing agents to photograph documents, maps, or enemy installations without raising suspicion. Playing cards are used to hide detailed escape and evasion maps, printed on silk and folded in such a way that they can pass unnoticed during inspections. Invisible inks and chemical agents are also employed for secret communication and documentation, while forged identification cards, travel permits, and counterfeit currency are produced in large quantities to support agents operating under false identities.

| Selection |

Most Americans who volunteered for service in Special Operations or the Operational Groups of the Office of Strategic Services during the Second World War were drawn from the ranks of high-aptitude, citizen-soldiers already serving in the wartime armed forces. These individuals had completed basic and, in many cases, advanced military training. However, the Office of Strategic Services demanded far higher levels of proficiency, physically, mentally, and emotionally. Given the unpredictable and hazardous nature of missions conducted behind enemy lines, the Office of Strategic Services developed rigorous selection processes to identify individuals capable of thriving in high-pressure and unconventional environments.

By 1944, the Office of Strategic Services had introduced a sophisticated psychological assessment programme. Conducted at a secluded country estate in Fairfax County, Virginia, known as Assessment Station S, this programme involved a comprehensive three-day evaluation. Candidates were tested not only for physical and intellectual aptitude but also for judgement, independence, emotional stability, and their ability to operate effectively under stress. Exercises included simulated interrogations and tasks engineered to frustrate or confuse, such as assembling a complex wooden platform while covertly hindered by others posing as assistants. The goal was to evaluate the entire personality and psychological resilience of the candidate.

These assessments revealed that the most effective Office of Strategic Services personnel, whether acting as saboteurs in France, spies in Germany, commandos in Burma, or clandestine radio operators in China, shared core attributes. They were confident, emotionally secure, intelligent, creative, and capable of functioning independently in ambiguous and high-risk conditions.

In 1942, when Garland H. Williams first began organising training for covert operations, he sourced instructors from two principal backgrounds. The first group comprised former law enforcement officers, many with experience in undercover work, firearms, and martial arts. These instructors were drawn from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the United States Customs Service, the United States Border Patrol, and various state and municipal police forces.

The second group consisted of activated military reservists. United States Army engineers provided instruction in demolitions and explosive handling. Military police trained recruits in pistol marksmanship and hand-to-hand combat. Infantry officers taught courses in the use of small arms, hand grenades, light and heavy machine guns, mortars, map reading, fieldcraft, and tactical movement. Members of the United States Army Signal Corps instructed students in wireless telegraphy, encryption, and codebreaking. Paratroopers oversaw airborne infiltration training, while officers from the United States Navy and the United States Coast Guard taught watercraft handling and amphibious landing techniques.

However, early instructional efforts were not without difficulties. Law enforcement officers, despite their technical expertise, often struggled to adapt to the Office of Strategic Services’ mission. Their training emphasised law enforcement and the apprehension of fugitives, whereas clandestine operatives behind enemy lines were expected to break enemy laws and avoid capture at all costs. Likewise, some regular army officers found it difficult to adapt to the more flexible and irregular methods of the Office of Strategic Services. Their adherence to formal military structures sometimes conflicted with the unconventional nature of covert warfare.

Recognising this challenge, Colonel William J. Donovan deliberately sought individuals who were bold, unorthodox, and willing to take calculated risks. Over time, many law enforcement and career military instructors were reassigned, and the organisation came to rely primarily on wartime citizen-soldiers—individuals who had entered service from civilian life and who demonstrated exceptional resourcefulness and adaptability.

Instructors were not the only ones selected with care. The Office of Strategic Services also sought out independent-minded and intelligent trainees. One recruiter recalled searching for individuals who might have appeared problematic to conventional military authorities, such as freelance journalists, trade union organisers, and political activists. What regular officers might consider flaws—such as a tendency to question orders—were seen by the Office of Strategic Services as indicators of initiative and strength of character.

Recruitment focused almost entirely on those already serving in uniform during wartime. The Personnel Procurement Branch of the Office of Strategic Services scouted training bases and advanced schools across all military branches, seeking volunteers with strong intellect, foreign language proficiency, and a willingness to undertake dangerous and undefined missions.

In the end, the Office of Strategic Services built its clandestine ranks not from professional soldiers or career officers, but from civilians-turned-soldiers, highly capable, unconventional, and resilient individuals whose success behind enemy lines would have an outsized impact on the Allied war effort.

When the United States entered the Second World War, Colonel William J. Donovan’s fledgling organisation was in its infancy. The Coordinator of Information, established in 1941, employed just over 2,000 individuals. However, as American involvement in the conflict deepened, this small agency rapidly expanded into the Office of Strategic Services, which reached a peak strength of at least 13,000 personnel, possibly more.

This dramatic growth presented immediate challenges. As missions multiplied across Europe and Asia, the Office of Strategic Services found itself needing to recruit, train, and deploy operatives into the field at the same time. Each operational branch, Special Intelligence, Special Operations, X-2 Counter-Intelligence, and Morale Operations, created its own training regimen. In the early years, many male recruits received their initial paramilitary instruction in national parks such as Catoctin Mountain Park or Prince William Forest Park.

By August 1942, headquarters of the Office of Strategic Services began advocating for improved coordination between the diverse and largely independent training efforts. Several initial attempts were made, including the creation of a joint training directorate. Finally, in January 1943, Colonel Donovan established a dedicated Schools and Training Branch to oversee and ultimately operate all training facilities. This branch was designed to be independent from the operational units.

Despite this structural reform, the Schools and Training Branch experienced difficulties from the outset. Internal disagreements and strained relationships with the United States Armed Forces led to the departure of key early figures such as Garland H. Williams and his successor Kenneth H. Baker. Baker, a psychologist from Ohio State University and a reserve officer in the United States Army, had been the first director of the branch, but by the summer of 1943, the Schools and Training Branch was in disarray.

The turning point came in September 1943 with the appointment of Dr. John McConaughy, then President of United China Relief. Colonel Donovan appointed Colonel Henson Langdon Robinson, a graduate of Dartmouth College, World War I veteran, and prominent businessman from Springfield, Illinois, as deputy director. Robinson had previously managed operations at headquarters and was now tasked with restoring order and efficiency to the Schools and Training Branch.

Over the following two years, the Schools and Training Branch attempted to coordinate the widespread and inconsistent training efforts established by the operational branches, particularly Special Intelligence and Special Operations. Although headquarters granted the branch increasing authority over domestic and, as of August 1944, overseas facilities, full control was never achieved. The operational branches retained primary influence over their own training programmes, often resisting efforts at centralisation.

In early 1944, the Schools and Training Branch introduced a two-week introductory programme intended for all operational personnel, including those assigned to Special Intelligence, Special Operations, X-2 Counter-Intelligence, and Morale Operations. Known as the “E Course,” this programme was first taught at Area E. However, it was met with considerable criticism, particularly from the Special Operations branch, which believed the course was too heavily focused on intelligence and insufficiently practical. The operational branches also faulted the branch for outdated instruction and poor coordination with field requirements.

In response to these concerns, Dr. McConaughy acknowledged the branch’s shortcomings, noting that training had followed the launch of operations rather than preceding it. The Schools and Training Branch, he said, had long been treated as “the tail of the dog,” lacking leadership, support, and institutional standing.

Although Area E was closed in July 1944, the idea of a unified basic training programme persisted. A revised version of the E Course was adopted later that year, following substantial modifications. This new curriculum incorporated field-tested methods and aligned more closely with the needs of the operational branches. It was first approved by Special Intelligence, X-2 Counter-Intelligence, and Morale Operations, and eventually accepted by Special Operations as well.

The revised E Course launched in July 1944 and was delivered at Area A, Replacement Training Unit 11, Area F, and at the newly opened training centre on Santa Catalina Island off the coast of Los Angeles. Designed to provide an intensive introduction to the full spectrum of Office of Strategic Services activities, the course included instruction in undercover techniques, intelligence reporting, sabotage, demolition, small arms, unarmed combat, counter-espionage, and black propaganda. Typically completed in two to three weeks, the programme offered a general foundation upon which more specialised training could be built.

Simultaneously, the Special Operations paramilitary course, referred to as the “A-4 Course”, was conducted at multiple training areas, including Area A, Area B, Area D, Area F, and on Santa Catalina Island. This course focused on combat readiness and fieldcraft.

From mid-1943 through late 1944, the Office of Strategic Services training network operated at full capacity. As the organisation’s global responsibilities expanded alongside the broader Allied war effort, demands on the Schools and Training Branch grew considerably. The branch, by this time, employed around 50 individuals at headquarters and nearly 500 male instructors across domestic training facilities.

By the final year of the war, the number of Office of Strategic Services training sites in the United States had risen to sixteen. In addition to long-established areas in Maryland and Virginia, new facilities included Area M, a communications school at Camp McDowell near Naperville, Illinois, and eight installations in southern California. The most prominent of these western sites was the base on Santa Catalina Island, developed as the focus of training efforts shifted toward operations against the Japanese Empire.

On the West Coast, Phillip Allen was appointed head of training. Upon arriving from headquarters, he introduced a coherent, well-structured training system. With the exception of the Maritime Unit, which already had its own school on the island, the operational branches had no existing training presence in California, allowing Allen to establish a standardised system from the ground up.

The training programme on Santa Catalina Island began with the revised E Course, followed by advanced instruction in either Special Intelligence, Special Operations, Morale Operations, or a combination of them. Importantly, many instructors had recent overseas experience and brought current intelligence, field-tested tactics, and practical knowledge into the classroom.

Final field exercises on the island were demanding and often involved trainees of Korean American, Japanese American, and Korean prisoner-of-war backgrounds. These recruits were preparing for infiltration missions into Japanese-occupied Korea or Japan itself.

Advanced Special Intelligence trainees conducted infiltration simulations in northern Mexico, tasked with collecting and transmitting vital information using clandestine techniques. Meanwhile, advanced Special Operations personnel undertook survival challenges in isolated environments. Lieutenant Hugh Tovar, a Special Intelligence officer and Harvard University graduate of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, recalled being issued a carbine and a single round of ammunition before being dropped on Santa Catalina Island to survive for several days alone. He succeeded in the exercise and later deployed to China and Indochina.

| Training the OSS |

In the critical first six months following the United States’ entry into the Second World War, William J. Donovan and his staff focus their attention not only on building the structure of America’s first central intelligence agency but also on creating the training facilities necessary to prepare men and women for the dangerous and unconventional missions that lie ahead. These missions, espionage, sabotage, guerrilla warfare, and psychological operations, require far more than traditional military discipline. Donovan envisions an elite corps of operatives marked by initiative, resilience, ingenuity, and the ability to function independently behind enemy lines. Accordingly, the training programme emphasises both practical skills and the mental fortitude needed to succeed in the perilous world of covert warfare.

In January 1942, Donovan and his deputy, M. Preston Goodfellow, begin the process of establishing specialised training schools and recruiting instructors. They also launch efforts to form a cadre of special operations troops. By the second week of February, Donovan is presented with a draft letter addressed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, formally requesting authorisation to recruit 2,000 enlisted men at the ranks of sergeant, staff sergeant, technical sergeant, and master sergeant. While most of these would form the core of the foreign-speaking units Donovan envisions, individuals capable of blending into occupied populations and leading local resistance groups, some would serve as the training cadre and instructional staff.

Donovan also requests positions for 48 commissioned officers to serve as the core of the special operations training schools. Although the War Department agrees in principle and assists in securing sites and staffing for the training camps, it is slow in allocating the full number of personnel Donovan needs to implement his vision.

In early January 1942, M. Preston Goodfellow recruits Garland H. Williams to help design and organise the training programme. Williams is not a conventional military officer. A career law enforcement official, he has spent over a decade with the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, eventually becoming the director of its New York office, one of the most senior posts in the agency. He subsequently requests and receives an instructional posting at the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, followed by a tour at the Chemical Warfare School in Aberdeen, Maryland. His combination of law enforcement experience, intelligence training, and instructional background makes him an ideal candidate to help shape the unconventional training environment Donovan envisions.

By early 1942, Goodfellow, working closely with both Military Intelligence and the Coordinator of Information, is highly impressed by Williams’ record and his suitability for building a clandestine warfare school. With his proven ability to design intelligence curricula and manage undercover operatives, Garland H. Williams becomes one of the foundational figures in creating the training infrastructure that supports Office of Strategic Services missions around the globe.

Following its expansion from the Office of the Coordinator of Information, the bulk of the Office of Strategic Services establishes its headquarters near the junction of 23rd Street and E Street in Washington, D.C. This complex, appearing to nearby residents as an unremarkable mix of government offices and apartment buildings, becomes widely known as the “Navy Hill Complex,” “Potomac Hill Complex,” or simply the “E Street Complex.”

Training for Office of Strategic Services personnel is a significant undertaking. At Camp X near Whitby, Ontario, an assassination and elimination training programme is operated by the British Special Operations Executive. Here, notable experts such as William E. Fairbairn and Eric A. Sykes instruct trainees in knife combat and other close-quarters techniques. Many Office of Strategic Services members receive their initial training at this facility, which George Hunter White, an alumnus of the course, later famously refers to as “the school of mayhem and murder.”

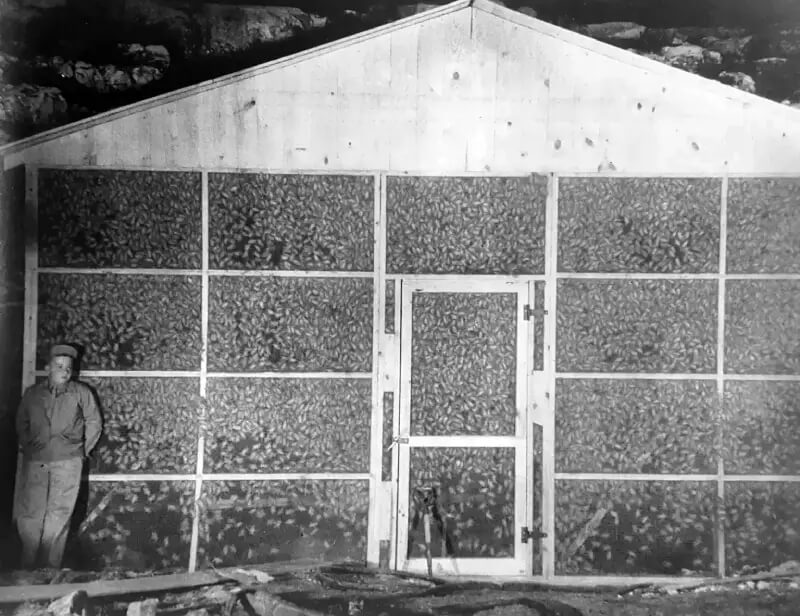

From these initial efforts, the Office of Strategic Services establishes multiple training camps across the United States and, subsequently, abroad. Prince William Forest Park, then called Chopawamsic Recreational Demonstration Area, becomes the site of extensive communications training (Area C) and some Operational Groups (Area A). Meanwhile, Catoctin Mountain Park, now the site of Camp David, hosts Training Area B, where Special Operations personnel receive parachute, sabotage, self-defence, and leadership training, following the model established by the British Special Operations Executive.

The Office of Strategic Services’s Secret Intelligence branch, considered the most clandestine of all, establishes Training Areas E and RTU-11, “The Farm”, in country estates converted for espionage instruction. Recruits in this programme are introduced into the murky world of espionage, learning tradecraft within spacious manor houses surrounded by horse farms. Morale Operations training, focusing on psychological warfare and propaganda, is also developed during this period.

The Congressional Country Club in Bethesda, Maryland, known as Area F, becomes the primary Office of Strategic Services training facility. On the West Coast, the facilities now occupied by the Catalina Island Marine Institute at Toyon Bay on Santa Catalina Island previously serve as an Office of Strategic Services survival training camp. The National Park Service later commissions a study of these Office of Strategic Services training sites by Professor John Chambers of Rutgers University.