| Page Created |

| July 8th, 2025 |

| Last Updated |

| October 26th, 2025 |

| The United States |

|

| Related Pages |

| Project Scam Dukw Landing Craft, Assault U.S. Army Rangers Operation Overlord Operation Neptune Omaha Beach Omaha Beach, Widerstandsnest 75, Pointe du Hoc Omaha Beach, Provisional Ranger Group Omaha Beach, PRG, Force A, Pointe du Hoc Omaha Beach, PRG, Force B Omaha Beach, PRG, Force C Provisional Ranger Group, Assault on the Maisy Battery |

| June 6th, 1944 |

| Omaha Beach, Provisional Ranger Group, Force A, Pointe du Hoc |

| Podcast |

| Objectives |

- Destroy the German six guns of the 155-millimetre battery located on the cliff-top at Pointe du Hoc, which pose a serious threat to the success of the Allied landings on Utah and Omaha Beaches.

- Destroy any observation or fire control posts.

- Hold the position until relieved by follow-on forces advancing from Omaha Beach.

| Operational Area |

| Allied Forces | ||||

|

- 2nd Raider Battalion

- Company D

- Company E

- Company F

| Axis Forces | ||||

|

- Heeres-Küsten-Artillerie-Abteilung 1260 (2./1260)

- Batterie 2

- 716. Infantrie-Division

| Operation Flashlamp, June 5th, 1944 |

The first Operation Flashlamp raid on the Pointe-du-Hoc battery is conducted by the United States Army Air Forces on June 5th, 1944. The 379th Bombardment Group, departs from Royal Air Force Kimbolton in Cambridgeshire at 06:14. Of the forty-one B-17 Flying Fortresses assigned to the mission, thirty-six reach the target area and release a total of 427 bombs, each weighing 227 kilograms, just after 09:21. Although the bomb pattern lands approximately 150 metres from the designated target centre, the results are assessed as fair to good. Probable hits are recorded on at least two of the six 15.5-centimetre French artillery pieces at the site, and further damage is inflicted on infrastructure and the surrounding area. A German report acknowledges damage to one of the under-construction gun casemates, but details are scarce owing to the disruption caused by the Allied invasion the following day.

| Operation Flashlamp, June 6th, 1944 |

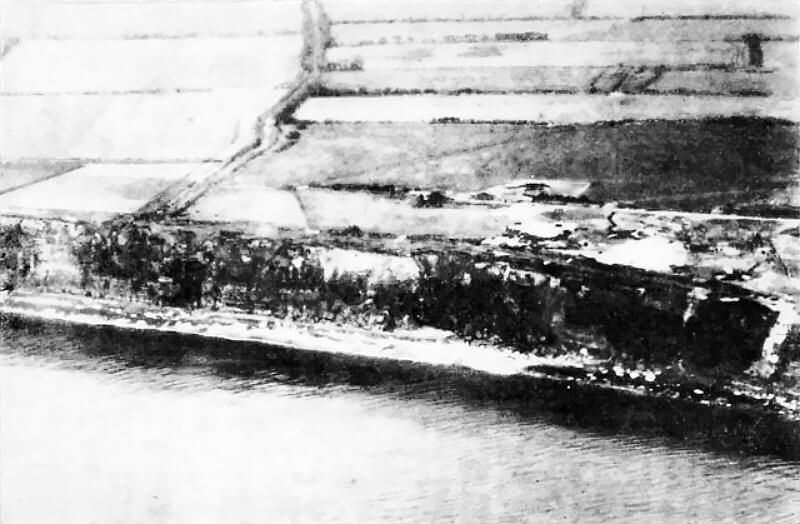

The heaviest air raid takes place in the pre-dawn hours of D-Day, conducted by the Royal Air Force. At approximately 04:45 on June 6th, 1944, the Pathfinder Mosquitos release their TIs over Pointe-du-Hoc, despite scattered cloud cover and flying at altitudes ranging from 2,100 to 9,100 metres. Moments later, 115 Lancaster bombers from RAF Bomber Command’s 5 Group commence their attack from lower altitudes between 1,800 and 3,600 metres. Over the course of thirty minutes, the Lancasters drop more than 575 metric tonnes of ordnance on the site, including 454-kilogram semi-armour-piercing bombs and 227-kilogram general-purpose bombs. This represents the largest single bombing concentration against Pointe-du-Hoc to date, exceeding the cumulative tonnage of all previous raids.

The airspace over the small coastal site becomes crowded, with near-collision risks forcing at least two bombers to abandon their runs. Nevertheless, the squadron reports describe the results as highly effective. Observers note that the battery position appears “flattened,” with its infrastructure severely damaged. The raid is regarded as a major success, substantially weakening the German position and reducing the threat posed to the Allied landings just hours later on the Normandy coast.

| Multimedia |

| Landing Phase, June 6th, 1944 |

Sixteen kilometres off the coast, H.M.S. Ben My Chree and H.M.S. Amsterdam heave to. Well before dawn, the Rangers, fully equipped and carrying ammunition and five days’ supply of K Rations, move to the boat deck. There, the Landing Craft, Assault wait. The Rangers begin loading into their assigned Landing Craft, Assault around 04:00. The Rangers are fortunate; their ship can lower the Landing Craft, Assault into the sea with the three- or four-man crew and passengers already aboard. Other units are not as lucky. Their men must climb down wet, swaying cargo nets into landing craft tossing violently in the waves below. At this stage, the craft are still hanging from the davits of the infantry landing ships. Colonel Rudder boards LCA 888 with Lieutenant James “Ike” Eikner of Headquarters Company. They decide to separate at the last moment to avoid risking both senior officers in the same boat.

A Naval Shore Fire Control Party of twelve men and a forward observer from the 58th Armored Field Artillery Battalion are attached to Lieutenant Colonel Rudder’s headquarters. The men are then distributed among the four Landing Craft, Assault carrying Company E.

At 04:30, two hours before H-Hour, the Landing Craft, Assault are lowered and begin their approach towards the coast. A moderate sea rises beneath them. Seasickness strikes almost immediately among the 225 Rangers. Many are overwhelmed. Others find some relief in the constant need to bail out water, as waves crash repeatedly over the bows.

Once launched, the Landing Craft, Assault push away from H.M.S. Ben My Chree and H.M.S. Amsterdam to prevent congestion. Sea conditions remain challenging. Winds blow at over 30 kilometres per hour and waves rise to about 1.5 metres. The small craft pitch and roll in the rough sea. Many Rangers become seasick. Visibility is poor at dawn, and an eastward-setting tidal current causes navigational errors.

Around 04:30, two Landing Craft Support (Medium) gunboats arrive to provide close support. The Landing Craft, Assault flotillas begin their final approach to the coast. Leading the formation is Motor Launch ML 304, a Fairmile B vessel. The Landing Craft, Assault follow in two columns, with Rudder’s craft leading the starboard line.

ML 304 is under the command of Temporary Lieutenant Colin Beever of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. Aged 40, Beever has served aboard ML 304 since December 1943. Navigation proves difficult in the blackout conditions. A dense mist and early morning fog add to the challenge. The coxswains must watch closely for the faint, glowing wakes of the boats ahead.

Temporary Lieutenant Beever dismisses traditional dead reckoning as unreliable in the rough sea. The convoy’s slow speed, strong currents, and high winds make accurate navigation by this method nearly impossible. Instead, ML 304 initially relies on a Q.H. 2 “Tree” radio navigation set. This equipment receives cross-bearings from transmitters in Britain and claims an accuracy of 45 metres. The motor launch also carries a Type 970 radar set, but it cannot resolve the low-lying, indistinct shoreline.

Around 05:30 hours, as dawn breaks, Beever finally sees the coast. However, much of the shoreline remains obscured by smoke from naval and aerial bombardments. Soon after, both the radio set and radar begin to fail due to a power fault. Beever reverts to dead reckoning and visual cues. He expects gun flashes from Pointe du Hoc but sees none. Available reconnaissance photos provide little visual assistance. Pointe du Hoc and Pointe-et-Raz-de-la-Percée appear nearly identical from seaward.

While still nearly 5 kilometres from the coast, Temporary Lieutenant Beever alters course to port, steering towards Pointe-et-Raz-de-la-Percée, mistakenly believing it to be Pointe du Hoc.

At 05:40 hours, approximately 3.6 kilometres from shore, LCT 413 receives the codeword “Splash.” This signals the launch of four DUKW’s fitted with extensible Swan ladders. They disembark prematurely into the sea and attempt to join the Landing Craft, Assault flotilla. The amphibious vehicles struggle to keep pace due to the heavy ladders and the choppy water. Their progress is slow and uncertain. The error in navigation and the harsh conditions continue to place the entire Pointe du Hoc assault in jeopardy.

Rough seas thirteen kilometres offshore causes LCA 860, carrying Captain Harold K. Slater and twenty men of Company D, to swamp in 1.2-metre waves. Rescue craft recover the men and return them to England. They later rejoin the battalion on D+19.

Ten minutes later, one of the supply LCA 914 sinks with only one survivor. The second supply craft, LCA 1003, quickly takes on water and is forced to jettison the rucksacks of Companies D and E to stay afloat. Other landing craft also suffer from flooding. Crews resort to bailing water with helmets to assist the pumps. From the start, all Rangers are soaked by sea spray.

Despite being wet, cold, and cramped during the three-hour crossing, the Rangers remain fit for combat upon landing. They avoid seasickness, unlike many troops at Omaha Beach. However, their soaked ropes and ladders become far heavier than intended, reducing their effectiveness.

The surviving nine Landing Craft, Assaults of the assault wave maintain good formation in a double column. They prepare to fan out as they near the objective. Unfortunately, the guide craft loses its bearings. It turns the column towards Pointe de la Percée, approximately five kilometres east of Pointe du Hoc.

The British destroyer H.M.S. Talybont, a Type III escort destroyer, which has taken part in the early bombardment at a range of 4.3 kilometres, observes the Ranger flotilla heading off course. The fall of shot from U.S.S. Texas is obvious, yet the Landing Craft, Assault turn east. As the Rangers correct their approach and come under fire, H.M.S. Talybont closes range.

At 05:40 H.M.S. Talybont, takes station in the fire support channel. It lies midway between U.S.S. Satterlee and U.S.S. Thompson. At 05:50 it begins firing at less than 800 metres against unseen targets on the cliff top. The aim is to saturate the position before the Rangers arrive.

Naval gunfire begins at 05:50 on D-Day. Battleships including U.S.S. Texas, with 356-millimetres main guns, concentrate their fire on Pointe du Hoc. At 06:10, twenty minutes before H-Hour, the naval bombardment halts. This pause allows eighteen USAAF medium bombers to target the battery at Pointe du Hoc. They release a total of 33 metric tonnes of bombs. Owing to poor weather conditions, many similar air strikes are delayed to avoid damaging the landing beaches with bomb craters. However, at Pointe du Hoc, no such delay is given.

At 06:00 a Ranger landing craft passes the H.M.S. Talybont. The destroyer’s crew do not yet realise the flotilla is steering east toward Pointe de la Percée instead of Pointe du Hoc. At 06:15 fire is lifted briefly, then resumed.

Colonel Rudder, aboard the lead Landing Craft, Assault, realises the error and orders the flotilla westward. The correction is successful, but the delay is significant. Instead of landing at H-Hour (06:30), the first Rangers reach shore at approximately H+38 minutes. Around 06:30 the Rangers’ mistake is corrected. Motor Launch 204 turns west for the correct target.

The navigational error has further consequences. The westward correction now brings Rudder’s Landing Craft, Assault along a coastal route, parallel to the cliffs and only a few hundred metres offshore. This path exposes the craft to fire from German strongpoints spread along nearly five kilometres of coast. Fortunately, enemy fire is scattered and inaccurate.

H.M.S. Talybont shifts to designated targets 81 and 82. At 06:40 its gunners observe German fire against the rear DUKWs. At least two light machine guns are active. The DUKWs take casualties. H.M.S. Talybont responds with 102-millimetre and 40-millimetre weapons, concentrating on the cliff face and top. Enemy fire slackens, though two DUKWs are disabled.

At 06:46 gunfire continues shelling targets 81 and 82. The Rangers suffer no further casualties from these positions. At 07:00 fire is lifted. Yet small-arms fire from Pointe du Hoc still reaches the assault wave. U.S.S. Satterlee engages these remaining positions. At 07:03 H.M.S. Talybont switches to other targets, and by 07:10 it withdraws from the fire support area. The destroyer reports targets 67 and 77 completely neutralised. Targets 81 and 82, engaged for twenty-five minutes before H-Hour, are judged only 60 percent suppressed. It is believed that up to four German light machine guns remain in action against the Rangers as they make their landings.

| Force C |

The 38-minute delay alters the course of the battle over the next two days. The most important is the landing of Force C. Force C, the main Ranger force with eight companies, follows behind from the Force A transports. They await the signal of success from the Point: two flares fired from 60-millimetre mortars. By 07:00, with no signal received, Colonel Max Schneider prepares to execute the contingency plan.

Faced with confusion and silence from Force A, Turnbull and Schneider conclude that the Pointe du Hoc landing has not succeeded. At 07:15, they jointly decide to execute Plan 2 and divert Ranger Force C to Dog Green Beach. Although they do not know it at the time, the fifteen-minute delay in reaching this decision spares them from heavier losses. Dog Green Beach remains under fierce fire earlier in the hour.

The landing plan also requires adjustment. Because the column now approaches from the east, Company D cannot swing out to assault the western side of the promontory. To ensure a simultaneous assault, all nine Landing Craft, Assault deploy into line abreast and land together on the eastern side of Pointe du Hoc.

The delay gives the enemy time to regroup. Naval gunfire and bombing had ceased at 06:25, just before H-Hour. As a result, the German garrison has nearly 40 minutes to recover from the effects of the preliminary shelling. As the Landing Craft, Assault near the cliffs, the Rangers come under small-arms and automatic fire. German troops are visible near the cliff edge. However, no artillery fire is observed from the position.

Around 07:00, as Force A nears the shore, the effects of the earlier bombardment have faded. The Germans, no longer stunned, begin to reorganise atop the cliffs. As the Rangers close in on the beach, enemy fire intensifies. Rifle and machine-gun fire pours down from the battery above.

The low freeboard of the Landing Craft, Assault, only 45 centimetres, had previously helped present a small target. Now, it offers little protection. Incoming fire sweeps across the landing craft. Each Landing Craft, Assault suffers casualties, further reducing the already thin ranks of Force A.

In LCA 884, three Rangers are wounded. The craft responds with bursts from its Lewis guns, supported by the Rangers’ Browning Automatic Rifles. Meanwhile, the U.S. destroyer U.S.S. Satterlee, positioned just over two kilometres from the cliffs, observes German troops assembling at the top. She opens fire with her main battery and machine guns to support the Rangers’ approach. Lieutenant Beever’s Motor Launch 304 joins the engagement, bringing to bear a 47-millimetre gun, a 20-millimetre cannon, and two machine guns.

Together, their fire suppresses the German positions long enough for the final approach to be completed. Though not without losses, the last run-in avoids catastrophic casualties.

At 07:08, as the first Landing Craft, Assault begin grounding beneath the cliffs, Colonel Rudder’s staff breaks radio silence. They transmit the signal for Colonel Schneider to land at Vierville. The message is received and acknowledged.

| Scaling the Cliffs, June 6th, 1944 |

At 07:08, nine Landing Craft, Assault start to touch down along a 460-metre front beneath Pointe du Hoc. The rightmost craft lands directly under the tip of the promontory. The others space out evenly along the cratered beach. Although the distance between some boat teams is small, each operates independently as planned, confronting its own problems of escalade and enemy fire.

The beach between sea and cliff is no more than 27 metres wide and is heavily cratered by bombs and shells. In many areas, the beach is so deeply cratered that Rangers struggle to cross it. Some soldiers land neck-deep in water and find it difficult to wade ashore due to the slick clay bottom. Yet this devastated terrain offers some benefit. Craters provide cover from German stick grenades thrown from above, while the scattered rubble reduces their explosive effect. Only two casualties are recorded as being caused by these grenades, which rely on blast rather than fragmentation.

German soldiers are seen looking over the cliff edge. Several are hit and fall, tumbling down with loose rocks dislodged by the bombardment.

Among the chaos, two men from the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, are already on the beach. They are the sole survivors from a Dakota transport that crashed into the sea shortly after 01:00. Making their way west along the shoreline, they join the Rangers at the base of the cliff below the battery.

The debris and cratered beach also prevents the DUKW’s from advancing. The four specially modified DUKW’s are assigned to support the climbing Rangers. All the DUKW drivers are British Royal Army Service Corps drivers. These vehicles are fitted with 30-metre extension ladders, requisitioned from the London Fire Brigade. The intention is to use them as mobile assault ladders, capable of reaching the top of the cliff from the beach.

As these DUKW’s approach Pointe du Hoc, one is struck by a German 20-millimetre cannon. It sinks in the channel, five of the nine men aboard are killed or wounded. The remaining three vehicles reach the water’s edge, but the terrain proves impassable. Deep shell craters and soft sand bog them down well short of the cliff base.

Realising they cannot reach the rock face, Lieutenant Colonel James E. Rudder orders the DUKW crews to raise their ladders in place and provide supporting fire. The men elevate the ladders vertically and begin firing from the rungs using Browning Automatic Rifles. This improvised tactic proves effective, delivering suppressive fire at German defenders positioned on the cliff-top. At least two of the DUKW drivers take part in the assault beyond their transport role. Corporal Good and Private Blackmore climb the cliffs using rope ladders. Once on top, they join the Rangers in the fighting. Both serve as riflemen in the line.

When ammunition runs short, Corporal Good and Private Blackmore climb back down the cliffs. Under fire, they recover the Vickers machine guns from the DUKW’s. They then return up the ladders and bring the weapons into action.

Private Blackmore is wounded in the foot ater that day. After receiving first aid, he goes back to the front line. He rescues a badly wounded Ranger under machine-gun and mortar fire. He volunteers to carry ammunition forward, salvage supplies from the beach, and repair weapons. He continues until evacuated on June 7th, 1944. Corporal Good stays and fights with the 2nd Ranger Battalion until Pointe du Hoc is relieved. Besides the two DUKW drivers, British sailors from beached Landing Craft Assault also take part in the defence of Pointe du Hoc.

As the Landing Craft, Assault approach the narrow beach, they come under machine-gun and mortar fire. Despite this, the craft motor forward, closing in as near as possible to the base of the cliffs. Upon beaching, sometimes just before, crews trigger the J-Projectors. These devices launch grapnel-carrying rockets. They fire with loud bangs and sharp whooshes. One Ranger describes a “loud explosion” as the rockets launch at the same moment the ramps drop.

The initial results are inconsistent. Heavy surf have thoroughly soaked many of the ropes. Waterlogging increases their weight dramatically. As a result, several rocket lines fail to reach the cliff tops. In some cases, the rockets lack the power to draw out the full length of the ladder or rope. Reports state that “not more than half the length of rope or ladder was lifted from the containing box.” The rockets simply do not generate enough thrust to extract the sodden lines fully, and the grapnels fall short.

Despite the initial difficulties, most Landing Craft, Assault manage to place at least one or two climbable ropes on the cliffs. An official summary notes that “on only two craft had the mounted rockets failed to get at least one rope over the cliff top.” This means that seven or eight craft succeed in deploying viable lines or ladders, as intended. Matters worsen as most of the sectional commando ladders, lashed to the topsides of the Landing Craft, Assault, have been washed away by the heavy seas.

Where the rocket systems and equipment fail, the Rangers improvise. They use handheld grapnel launchers. One such device famously snags the cliff edge, allowing several men to climb before the rope is shot through. Others deploy extension ladders carried aboard.

Meanwhile, German defenders begin to react. They fire down at the beaches, targeting Rangers and cutting ropes that do reach the top.

As the Rangers cross the open beach, grenades roll down from the cliff edge. Scattered small-arms fire comes from above. Enfilade fire, including automatic weapons, strikes from the German position to the left. Once the Rangers reach the base of the cliff, they find partial cover behind rubble mounds. German troops above must expose themselves to throw grenades or take aim.

Naval fire support begins at this critical moment. The destroyer U.S.S. Satterlee observes the Landing Craft, Assault grounding under fire. She opens with her 127-millimetre main battery and 40-millimetre guns, targeting German firing positions on the cliff top. Commander J. W. Marshall later assesses this fire as decisive in helping the Rangers reach the cliffs. However, this perception contrasts with that of many Rangers, only three or four of whom recall naval support at the time. One is Colonel Rudder, who is nearly hit by a detonation that dislodges part of the cliff above him. Some believe it is naval fire; others suspect German booby-traps using naval shells suspended over the edge.

Despite confusion and scattered resistance, the assault proceeds. Approximately 15 Rangers are wounded or killed on the beach, most by fire from the left. Within ten minutes of landing, the first Rangers begin reaching the cliff top. The boat teams, described below from right to left, make their respective climbs.

| LCA 888, Colonel Rudder’s Craft |

Colonel Rudder’s landing craft, LCA 888, is the first to reach the beach. Aboard are fifteen Rangers from Company E and six men from his headquarters, including Lt. J. W. Eikner, communications officer. As they land, enemy soldiers are spotted on the cliff edge. When Sergeant Boggetto shoots one of them with a Browning Automatic Rifle, the others vanish from sight.

With the rocket-propelled grapnels failing, two Rangers, both skilled in free climbing, attempt to scale the cliff without ropes. Their effort is short-lived. The shell-damaged cliff is layered with slick clay and crumbling rock. The wet surface gives way too easily to allow a firm grip. Knife-holds are impossible. The bombardment, however, has brought down part of the cliff, creating a ramp of rubble roughly twelve metres high.

A section of commando ladder with a toggle rope attached is carried to the top of the ramp and set up. One Ranger climbs the ladder and cuts a foothold into the cliff face. Standing in the hold, he steadies the ladder while a second man ascends. This process is repeated until Technician Fifth Grade George J. Putzek reaches the edge. Lying flat, he braces the ladder on his arms as a man below climbs up the toggle rope, then the ladder.

From that point, the climb becomes easier. The first men over the top move a few metres inland to secure the area for others. Bomb craters provide ample cover. No enemy is seen. Within fifteen minutes of landing, all Company E men from LCA 888 have reached the cliff top and are ready to move forward. Colonel Rudder and his headquarters staff remain below, taking shelter from enfilade fire in a shallow cave at the base of the cliff.

By 07:25, Lieutenant J. W. Eikner establishes communications and signals the successful landing. At 07:30, he transmits the code for “Men up the cliff.” When he sends “Praise the Lord” at 07:45, indicating all Rangers have reached the top, no reply is received. The failure to relay clear information delays higher command’s awareness of the situation atop Pointe du Hoc.

| LCA 861, Company E, 1st Lieutenant Theodore E. Lapres Jr. |

This craft grounds about 23 metres from the cliff. Meanwhile, LCA 861 grounds approximately 23 metres from the cliff. A platoon of Company E commanded by 1st Lieutenant Theodore E. Lapres, Jr. is aboard. Rockets are fired in sequence, but all ropes fall short. The wet ropes are too heavy; some do not even unspool fully from their boxes. Crossing the beach, the Rangers are hit by grenades. Two men are wounded. Three or four German soldiers fire from the edge, but Rangers at the stern return fire and force them to withdraw.

The platoon carries smaller, hand-fired grapnels ashore. A hand-carried rocket is fired 14 metres from the cliff and catches. Private First Class Harry W. Roberts climbs first. The rope slips or is cut, and he falls. A second rocket is fired, and Roberts climbs again. He reaches the top in 40 seconds and anchors the rope. It later fails under the weight of the next man. Roberts is temporarily stranded but is recovered using a rope thrown up from a mound of debris.

Five men, including Lieutenant Lapres, join Roberts atop the cliff. They immediately advance toward the northern observation post. Ten minutes have passed since touchdown. During the assault, a sudden and violent explosion shakes the cliff face. The blast half-buries Private First Class Medeiros beneath a cascade of rock and mud. The source of the explosion remains uncertain.

It is believed to be either a naval shell or a concealed mine placed by German defenders. The mine is likely suspended over the cliff edge, wired to a manual firing device, and equipped with a short-delay time fuse. The Germans have prepared several such traps along the Atlantic Wall.

Elsewhere on the coast, only a few of these improvised cliff-edge mines are later found intact. Most are assumed to have been triggered or destroyed during the intense naval and aerial bombardment prior to the landings.

In spite the explosion, private Medeiros and four other Rangers from LCA 861 quickly reached the cliff top. Without waiting for further reinforcements, the six Rangers, including Lieutenant Lapres, move out towards their objective: the German observation post built into the tip of Pointe du Hoc.

| LCA 862, Company E, 1st Lieutenant Joseph E. Leagans |

Landing approximately 90 metres left of LCA 861, LCA 862 lands with fifteen Rangers and Lieutenant Johnson’s Naval Shore Fire Control Party aboard. Like many others on the narrow beach, they come under machine-gun fire from the east. One man is killed, another wounded, and two more suffer injuries from grenade fragments.

Unlike most other craft, LCA 862 fires its grapnels only after reaching the shore. One plain rope and two toggle ropes reach the top, though one toggle rope dislodges. Lieutenant Leagans, Staff Sergeant Joseph J. Cleaves, and Technician Grade 5 Victor J. Aguzzi climb the remaining two ropes. They fall into a shell crater at the top and are soon joined by two more Rangers. Without waiting, they move out to their objective.

| LCA 722, Company E |

Twenty metres to the left of Colonel Rudder’s craft, LCA 722 touches down. On board are fifteen Rangers of Company E, five men from battalion headquarters, a Stars and Stripes photographer, and a British Commando officer. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas “Tom” Hoult Trevor, OBE, Welch Regiment, is the former commanding officer of No. 1 Commando and now serves at Combined Operations Headquarters as liaison to the U.S. Rangers. He had been involved in training the Rangers in Britain before the invasion, particularly in cliff assault techniques. His role as a Combined Operations observer and liaison officer, is assessing the performance of the specialist equipment and the assault techniques that had been developed in the Great Britain. This boat also lugged an SCR-284 radio, pigeons, a 60-millimetre mortar, ammo, and demolitions.

Touchdown occurs at the edge of a crater. Private First Class John J. Sillman is hit three times but survives. Enemy grenades are ineffective.

Among the equipment landed are an SCR-284 radio, a 60-millimetre mortar, demolitions, and two pigeons. Technician Grade 4, C. S. Parker sets up the radio successfully. One ladder and one plain rope reach the cliff top. The rope lies in a crevice; the ladder is exposed but secure.

Technician Grade 5 Edward P. Smith ascends the rope. He reaches the top in three minutes and engages Germans with Sergeant Hayward A. Robey and Private First Class Frank H. Peterson. The mortar team remains below but soon abandons plans to fire from the beach due to enemy exposure. They ascend by 07:45.

| LCA 668, Company D, Lieutenant George F. Kerchner |

This craft is diverted from the west side to the centre of the line. It grounds short due to cliff debris. Rangers swim 6 metres to shore.

Sergeant Leonard G. Lomell, wounded while carrying a rocket and rope box, continues. Despite soaked ropes, three lines, one toggle and two rope ladders, make the top. Only the toggle proves climbable. Lomell’s men deploy an extension ladder on the talus. The combination of debris and ladder reduces the angle, making the climb possible. Two men go up by rope, the rest by ladder.

Twelve men move inland with Lomell and Lieutenant George F. Kerchner.

| LCA 858, Company D |

This craft ships water during the approach. The crew bail continuously to stay afloat. It arrives slightly behind the others.

The Rangers disembark into a deep crater, plunging into chest-high muddy water. One bazooka is rendered unusable. Three Rangers are wounded by machine-gun fire from the eastern flank.

Rockets are fired in sequence. All ropes are waterlogged. Only one hand-thrown line reaches the top. It lies in a crevice offering limited protection. The route to the base of the rope is exposed.

The Rangers move forward using debris for cover. One man assists the wounded to Colonel Rudder’s command post. The rest climb the single rope, using footholds in the cliff and a crater that reduces the final gradient. All are atop the cliff within 15 minutes.

As elsewhere, the team does not regroup after the climb. The lead men immediately begin independent movement toward objectives.

| LCA 887, Company F, Lieutenant Arman |

Company F’s craft are shifted eastward due to the mislanding of Company D. Few Rangers are aware of the displacement at the time.

LCA 887 experiences little difficulty from sea conditions or enemy fire on the approach to the shore. No equipment is lost. Enemy fire comes from both flanks. Two Rangers are wounded. The craft grounds approximately five metres short of dry beach. Shorter Rangers step directly into a flooded crater, receiving an unplanned soaking. Despite the immersion, no equipment failure occurs.

Sergeant William L. Petty’s Browning Automatic Rifle becomes soaked here and later muddied when he slips on the cliff face. However, the weapon functions perfectly when first used in combat. As the men disembark, small arms and automatic fire reach the landing area from both flanks. Two Rangers are wounded in this initial phase.

Lieutenant Arman quickly assesses the situation. The heavier ropes attached to the rocket launchers aboard the craft cannot reach the cliff from the water’s edge. He leads a detachment of Rangers in dragging four of the craft-mounted rockets, along with boxes of toggle ropes and assault ladders, out onto the sand.

This effort requires ten minutes of strenuous work under pressure. Once on the open beach, the men realise that the electrical connection required to fire the rockets is missing. Technical Sergeant Cripps volunteers to fire the rockets manually. Using his hot-box, he steps to within one metre of each launcher and triggers them directly.

Each ignition blinds Cripps momentarily and showers him with sand and debris. Between firings, he wipes his eyes, steadies himself, and proceeds to the next launcher without hesitation. He endures this process four times. Witnesses later remark that he appears almost unrecognisable by the end of the task. But all four lines go up the cliff.

The ropes, now in place, offer a means to scale the vertical face. Sergeant William L. Petty and several experienced climbers attempt to ascend the plain rope first. The attempt fails. The rope lies along a straight drop with no footholds. Wet, muddy hands and clothing complicate the climb.

Enemy fire continues to sweep in from the flanks. Petty then climbs one of the ladders. It fails when the grapnel pulls out. Technician Grade 5 Carl Winsch climbs another ladder under fire and reaches the top. Petty follows. They link up with two more Rangers in a shell crater and move toward their assigned objective.

| LCA 884, Company F, Lieutenant Jacob J. Hill |

LCA 884, positioned on the flank of the flotilla, comes under sustained enemy fire from the cliffs throughout the final five-kilometre approach. German defenders fire continuously from elevated positions. Three Rangers are wounded by fire from the left flank. Despite this, four grappling hooks manage to clear the cliff edge.

However, every rope attached to the grapples hangs fully exposed to concentrated small-arms fire. The ropes offer no cover and become immediate death traps. The only rope ladder to make it snags on boulders and hangs at an angle. Private William E. Anderson tries to scale the cliff unaided but fails. Several other Rangers attempt to climb without success. The Rangers, soaked and coated in mud from the shell-cratered beach, struggle with traction. The plain ropes, slick and fouled, become impossible to climb once one man attempts the ascent. Lieutenant Jacob J. Hill leads the team leftward, where they link up with LCA 883’s ropes and ascend using those ladders.

With no viable means to scale the cliff directly, the group repositions. They move leftward along the base of the cliff under fire. There, they find and make use of ladders previously launched and secured by the crew of Landing Craft Assault 883. The Rangers use these ladders to begin their climb towards the enemy-held summit.

| LCA 883, Company F, Lieutenant Richard A. Wintz |

LCA 883 is the final vessel to reach shore. It lands approximately 270 metres to the left of its assigned position. The craft comes in well beyond the fortified centre of the German defences at Pointe du Hoc. This location places it outside the immediate range of concentrated enemy fire striking the main landing zone.

A natural rib of rock along the cliff face shields the Rangers from the intense flanking fire that harasses their comrades to the west. The beach here is narrow but firm. The Rangers make a dry landing, free from craters and surf.

All six rocket-projected ropes fire successfully. Each line reaches the cliff top. This rare success allows the Rangers to follow their climbing plan in full, with each man assigned a specific rope. The ascent begins immediately.

Despite the favourable conditions, the climb proves difficult. Even the ladders offer only limited ease of movement. First Lieutenant Richard A. Wintz attempts to ascend a plain rope. He quickly finds no footholds on the slick, wet rock face. The rope, soaked and muddied, is difficult to grip.

Wintz reaches the top by pulling hand over hand. At the summit, he reports feeling utterly spent, admitting he has never been so exhausted in his life.

| Multimedia |

| Advance on the Cliff, June 6th, 1944 |

The first two major obstacles, landing and scaling the cliff, have been overcome. Despite the delayed arrival, German resistance proves weak and disorganised, except for the effective enfilade fire from the machine-gun position east of Pointe du Hoc.

The Rangers’ escalade equipment and training stand the test. Only two Landing Craft, Assault fail to get at least one rocket-propelled rope over the cliff. The hand-held projectors and extension ladders prove valuable as secondary means where rockets fall short. Only one boat team needs to use ropes deployed by another.

The three SWAN’s are rendered ineffective by craters at the waterline. One vehicle attempts to raise its ladder, but it fails. The ladder rests against the cliff at a steep angle, falling short of the top and unsteady due to wave motion.

Though the Special Warfare Assault Navigators fail to provide a reliable method for scaling the cliffs, they are not entirely without value. One SWAN, under the command of Sergeant Stiverson, offers limited fire support during the initial assault.

Stiverson raises the craft’s extendable ladder to cliff height. From behind a small steel shield, he mans twin Vickers K machine guns. Suspended in the air and swaying in the wind, he opens fire on German positions above.

The fire is largely inaccurate due to the unstable platform. Yet it proves psychologically effective. The sudden appearance of automatic fire from an unexpected angle unsettles the defenders. German troops immediately respond, directing heavy fire toward Stiverson’s exposed position.

Despite drawing intense return fire, the swaying platform proves difficult to hit. Stiverson continues firing until the volume of incoming rounds becomes overwhelming. He then gives the order to lower the ladder and withdraws the SWAN from the firing line.

The cliff face, damaged by naval and air bombardment, assists the Rangers. Debris at the base offers protection from flanking fire and reduces the effective climbing height. In some areas, rubble mounds and cut-back sections ease the ascent, especially when using extension ladders. The cliff edge itself is cratered, providing cover for the first men to reach the top.

The assault parties climb with speed, determination, and adaptability. They improvise when needed. This spirit is key to success.

By 07:40, within 30 minutes of touchdown, all assault elements, apart from casualties, command personnel, and some mortar crews, are atop the cliff. Between 30 and 40 Rangers remain below, most due to wounds or assigned duties. The bulk of the attacking force is now ready to move inland and complete its mission.

| Chaos on the Cliff and the Disappearance of the Guns, June 6th, 1944 |

Unlike many assault units at Omaha Beach, the men of the 2nd Ranger Battalion at Pointe du Hoc register no disappointment with the results of the pre-invasion bombardment. As they emerge over the cliff edge, they find themselves in a shattered landscape. The entire area has been torn apart by bombs and naval gunfire. Landmarks are obliterated. Craters and debris obscure every path, trench, and terrain feature.

The Rangers have studied this small area for months. Their maps and aerial photographs mark every position and contour. Now, they struggle to orient themselves. Even moving a few steps inland risks becoming disoriented. Cover is plentiful, but maintaining contact, even within a squad, is nearly impossible.

The nature of the attack contributes to the confusion. The Rangers are trained to advance quickly in small groups. As soon as a few men reach the top of a rope, they move off without waiting for the rest of their team. No time is spent forming platoons or establishing contact with adjacent groups.

During the climb, the focus is so intense that few Rangers are aware of what other boats are doing. Many are not even conscious that other teams are on the beach. Over a 15- to 30-minute span, small parties continuously reach the summit and fan out in all directions. At least twenty separate groups form this way. Their paths are impossible to trace precisely, just as it must be difficult for the Germans to discern the direction of the assault.

Yet despite this disorder, the operation follows a coherent plan. Each platoon has a defined first objective within the enemy’s defensive network. Every Ranger knows his target. The result is an attack that lacks a clear tactical pattern but achieves clear results.

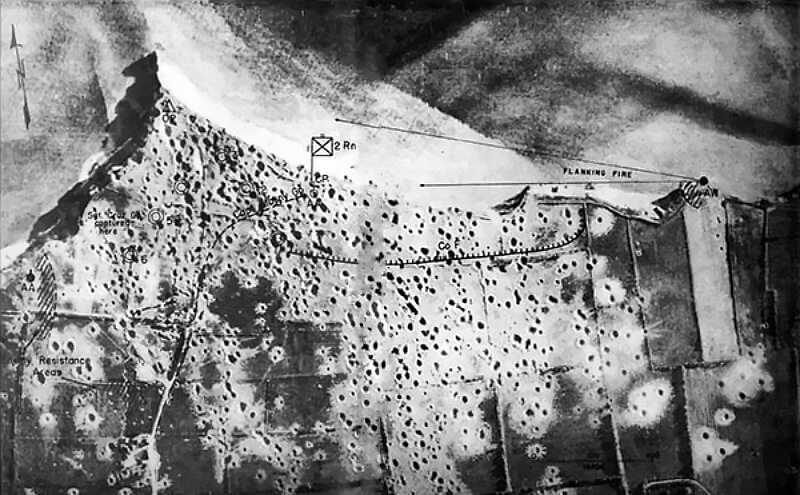

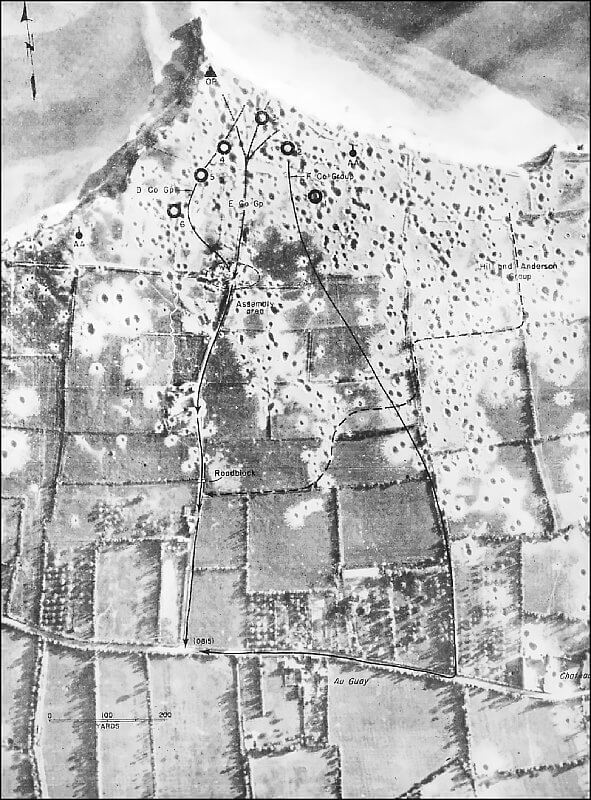

Company E is tasked with the observation post and Gun Position No. 3. Company D is to seize the western casemates, Positions 4, 5, and 6. Company F targets Gun Positions 1 and 2, and the machine-gun nest east of the fortified zone. Once these are neutralised, the companies are to regroup at a phase line near the southern edge of the defences.

From there, most of D, F, and E are to advance inland, cross the coastal highway 900 metres to the south, and establish a roadblock against German movement from the west. One platoon of Company E remains at the Point to defend the position alongside the headquarters group.

Inevitably, not all proceeds to plan. Some Rangers from Companies D and E fail to reach the assembly area. Others remain on the Point to respond to unforeseen threats. On the eastern flank, two boat teams from Company F are pinned down in action that lasts the entire day. Still, the assault mostly follows the original scheme, which relies on the ability of small, independent groups to achieve broader objectives. That confidence is justified.

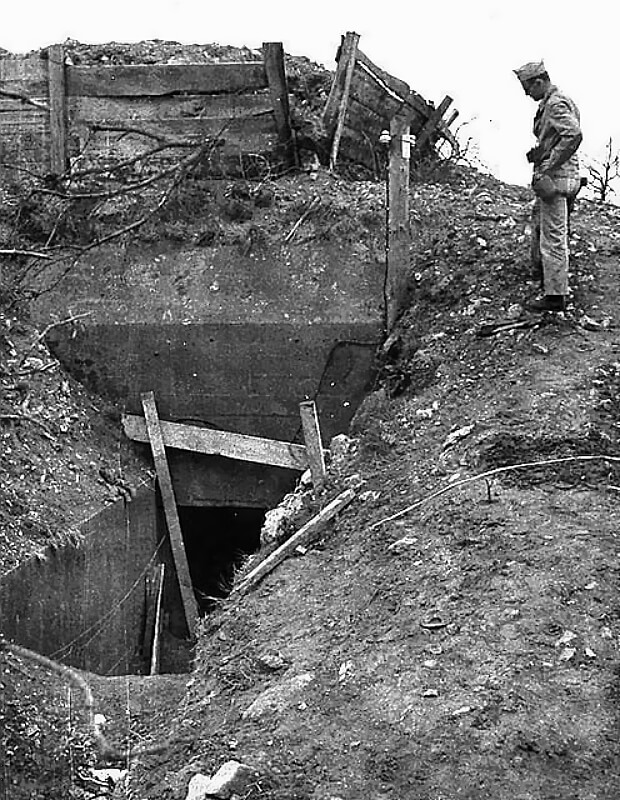

As the first parties move inland, they encounter no resistance except near the observation post. Most Rangers see no enemy. Few even notice the occasional fire from the western cliffs. The real problem lies in identifying the emplacements. The gun positions have been obliterated. The open mounts are reduced to rubble. The casemates are damaged. The 155-millimetre guns are nowhere to be found. It is now clear that they have been removed before the final bombardments. The Rangers push forward towards the southern assembly point.

| Combat at the Observation Post, June 6th, 1944 |

The only resistance comes at the very tip of the Point. As the first men from LCA 861 crest the cliffs, they find themselves 6 metres from the German observation post. Staff Sergeant Charles H. Denbo and Private Harry W. Roberts crawl forward. Small-arms and machine-gun fire erupts from firing slits. The Rangers throw four grenades, three enter the embrasures. The machine gun ceases fire, but Denbo is hit by a rifle round.

Lieutenant Lapres, Sergeant Andrew J. Yardley, Private William D. Bell, and Technical Sergeant Harold W. Gunther join them in a trench. Yardley fires a bazooka. His first shot hits the concrete. The second goes through the slit. The others dash around the position, while Yardley remains to cover the embrasure.

On the other side, Corporal Victor J. Aguzzi, from LCA 862, has taken position. He arrives with Lieutenant Joseph Leagans and Sergeant Joseph Cleaves. Technician Grade 5 LeRoy J. Thompson and Private Charles H. Bellows, Jr. join them. They spot a German throwing grenades over the cliff. Although the observation post is not their assigned target, they move to engage.

Bellows takes position near Gun Position 3. The others approach the enemy, who retreats into the structure. Aguzzi finds a shell crater to observe the entrance. Three Rangers attempt to flank the Observation Post from the east. Cleaves is wounded by a mine, the only mine casualty reported on D-Day. Thompson gets close enough to hear a radio inside. He shoots off its aerial and throws in a grenade. With no further sign of activity, he and Leagans proceed to their original objective inland.

Aguzzi, unaware of Lapres’ team approaching from the opposite side, remains in position. The two groups only discover one another by accident.

Moments later, four more men from LCA 861 reach the top. They join Yardley in the trench. Small-arms fire again erupts from the observation post. The Rangers debate how to proceed. Medeiros and Yardley consider retrieving explosives but lack covering fire. They decide to “button up” the Observation Post instead. The other three men pass by on the west side under cover.

At the trench’s end, fire from the Observation Post strikes again. Private George W. Mackey is killed. The remaining two make it inland. Despite their efforts, the Observation Post proves too strong to breach with hand weapons. Demolition charges are still at the beach and cannot be retrieved in time. The enemy remains sealed inside. Their radio antenna has been destroyed, and they have no functioning communications.

For the rest of D-Day and through the night, Yardley and Medeiros stay in position outside one entrance. Aguzzi holds his position at the other. Neither group realises the other is there. Though demolitions could have been used at Aguzzi’s entrance, none are brought forward. No movement is observed from within the Observation Post.

On the afternoon of June 7th, 1944, Rangers finally clear the post. Two satchel charges of C-2 explosives are thrown into the entrance. Aguzzi, still watching, assumes the enemy is dead. But eight uninjured Germans emerge with their hands raised. Only one dead body is found inside.

The Rangers never confirm how many Germans had manned the position. Like several others in the battery, the Observation Post is connected by tunnels. With limited numbers and pressing objectives inland, the Rangers lack the time and manpower to explore the underground complex fully.

| Contact with the Enemy Elsewhere, June 6th, 1944 |

Beyond the Observation Post, early Ranger parties encounter no resistance. However, later arrivals begin to draw fire. The German anti-aircraft position west of the Point fires on exposed Rangers. Sniping also begins near Gun Position No. 6.

A group from Company D, including survivors from LCA 858, operates near this position. Their actions are known only through one survivor, Private William Cruz. Slightly wounded on the beach, he is assigned to guard Colonel Rudder’s new cliff-top command post at 07:45. With Ranger Eberle, he sets out to silence a sniper near Gun Position 4.

They attract fire from the flanking Anti-Aircraft position. A sergeant orders them to engage. Sliding through craters, they join a larger group led by Technical Sergeants Richard J. Spleen and Clifton E. Mains. Eight to ten Rangers gather west of Gun Position 6, considering an attack.

They hesitate, fearing enemy artillery. Shells begin to fall from inland batteries. The group begins crawling forward. Suddenly, a German helmet rises from a crater. The Rangers recognise the deception. One man behind them fires. Almost immediately, enemy artillery and mortar rounds search the area.

Bunched too closely, the group disperses. Cruz retreats toward Gun Position 6 and finds himself alone. He calls out and hears Mains reply. After 15 minutes, with fire slackening, Cruz crawls back toward the Point.

As he nears the trenches near Gun Position 6, he sees Sergeant Spleen and two others vanish into a trench. Fire erupts again, from the Anti-Aircraft position and nearby enemy troops. Cruz hides in a trench. He hears enemy movement. German soldiers pass close by without seeing him. A few metres away, weapons are thrown into the air. He believes the other Rangers have surrendered.

After a long wait, Cruz slips back to the Command Post, just 180 metres away. He passes a pile of American weapons, eight or nine rifles, some pistols, and submachine guns. These are likely left behind by surrendered Rangers.

No one at the Command Post has seen the action. Ten men vanish without trace. Cruz’s account and the abandoned weapons are the only evidence of their fate. It is later assumed the Germans infiltrated from the Anti-Aircraft position, either via trenches or possibly emerging from underground shelters within the Point.

Cruz’s report alerts Colonel Rudder’s headquarters to threats on the western flank. The anti-aircraft position west of Pointe du Hoc remains a source of danger over the next two days.

| Advance Inland and Discovery of the Battery, June 6th, 1944 |

As the remnants of Companies D, E, and F spread out across the shattered battery, Colonel Rudder establishes his command post. He selects the site of a rockfall, on top of the cliff, near the centre of the position. A ramp of debris, created by the collapse, leads from a large crater on the cliff edge to the battery above.

This feature offers one of the few points of relatively easy access between beach and plateau. Its short vertical section allows movement with less risk than other parts of the cliff face. Rudder positions himself here to maintain control over the scattered elements of his force.

Amidst the chaos, a squadron of American fighter-bombers approaches. They have been summoned in support of the assault. As the aircraft begin their attack run over the cliff, Rudder quickly unfurls the Stars and Stripes across the rubble, hoping to prevent friendly fire.

One pilot recognises the signal. He waggles his wings and releases his bombs further inland. A potentially deadly mistake is avoided. However, not all such incidents are prevented.

Throughout the day, friendly fire from land, sea, and air contributes to Ranger casualties during the battle for Pointe du Hoc. The overlapping zones of fire and confusion on the ground make precise coordination nearly impossible.

The first Ranger elements to move inland are unaware of the renewed German resistance building near the Point. They receive only sporadic fire from the western flank. As they push beyond the destroyed fortifications, artillery and mortar rounds begin to fall. Light small-arms fire slows their movement. Two- and three-man parties begin to merge into larger groups.

Rangers from Companies E and D converge along the north-south exit track leading from the Point to the coastal highway. East of them, one boat team from Company F advances through the fields, avoiding the road. The early push inland now unfolds along these two main axes.

The largest group moving down the road includes Rangers from LCA 888 (Company E) and LCA 858 (Company D). First Sergeant Robert W. Lang leads fifteen men from LCA 888. They climb up late using extension ladders. After confirming Gun Position No. 3 is destroyed, they move south.

Artillery fire begins to track their movement, landing in salvos of three and shifting steadily toward the Point. Lang halts briefly to try a radio contact on his SCR-536, hoping to warn the naval fire support team that his men are now outside the fortifications. He fails to connect. When he moves forward again, fire lands between him and his men. He veers left into the fields, joins three Company E stragglers, and links up with Lieutenant Arman’s Company F party.

Company E Rangers reach the initial assembly point near the start of the exit road. There they join a dozen men from Company D, who have already checked Gun Positions 4 and 5. Sergeant Spleen and a few men remain near No. 6, holding back enemy fire from the anti-aircraft gun position on the western flank.

The combined D and E group now numbers about 30. Without waiting for reinforcements, they push south along the exit road. They move in single file, using a German communications trench for cover. German artillery, likely from 75 mm or 88 mm guns, continues to range the area. Machine-gun fire harasses them from the right flank. Small-arms fire comes from the left front.

Casualties rise sharply. Seven Rangers are killed. Eight more are wounded in the next few hundred metres. Yet their numbers grow as they link up with earlier advance parties or latecomers joining from the rear.

Their next objective is a cluster of ruined farm buildings, halfway to the highway. German snipers abandon the site before contact. Naval fire and enemy artillery continue to fall around them. The Rangers do not pause. The trench ends at the buildings, and the next cover lies 35 metres farther south, a communications trench crossing the road.

Men sprint across the open ground in twos, taking varied routes. Only one casualty occurs, a Ranger accidentally impales himself on a comrade’s bayonet while diving into the trench.

Ahead, two concrete pillars mark the entrance to the roadblock. Three German soldiers appear from the south. They duck behind the barrier when spotted. The Rangers fire with BARs. The enemy holds. A bazooka round, faulty, fails to explode. The Germans flee. The Rangers resume the advance.

Lapres reaches the next farm. The enemy has withdrawn. However, his small team is pinned down as the main group takes fire from both flanks. Unidentified friendly fire silences the German guns.

This proves the final resistance. Lapres and his men make the last few hundred metres without incident. As they reach the highway, they spot Technician 5 Davis of Company F coming in from the fields. Minutes later, a larger Company F group arrives from the east. It is now 08:15, just over an hour since landing. The objective is secured. Despite delays and losses, the advance has been swift. As one Ranger later remarks, “enemy shells followed us the whole way. That made us hurry.”

| Company F’s Parallel Movement, June 6th, 1944 |

Most of Company F remains near the Point, drawn into the firefight on the eastern flank. The team that reaches the highway comes from LCA 887. Lieutenant Arman and Sergeant Petty lead the group. Petty and three men move first, confirming Gun Position No. 2 is destroyed. They head inland, 180 metres east of the road.

At the edge of the fortifications, Lieutenant Arman joins with five more Rangers. He chooses to press forward rather than wait. They move through a suspected minefield, previously marked with wire and anti-glider posts. The bombardment has likely detonated or buried any mines. None detonate.

Mortar fire lands nearby but is inaccurate. The Rangers proceed in short bounds, covering each other from crater to crater. Near a ruined north-south lane, Sergeant Lang and three Company E men appear from the east and join them.

Arman leads the party down the lane. Petty scouts west toward the Château but finds no enemy. He rejoins the main party at the intersection with the highway. They turn west and follow the roadside hedges.

At Le Guay, a machine gun opens fire from 90 metres ahead. The Rangers scatter without injury. They outflank the hamlet from the south. Petty and two men surprise two Germans who rise from a concealed foxhole. Petty fires but misses. The enemy shouts “Kamerad” and surrenders. The Rangers find no further resistance. The machine gun has vanished.

Soon after, Arman’s team meets the Rangers advancing from the exit road.

| Independent Advance and Firefight near the Exit Road, June 6th, 1944 |

Other small parties reach the highway independently. One of these is led by Private William E. Anderson from LCA 884. He climbs using a ladder from the neighbouring craft. On top, he joins two others from his own boat. They try to silence a machine gun firing from the eastern cliff. They reach within 90 metres but cannot see the position. They return.

Anderson joins Praivate First Class John Bacho and Staff Sergeant James Fulton. They set off south across the fields. They use buddy tactics, leapfrogging forward under cover. Lieutenant Hill and two Rangers join them. Sniper fire is heard, but not close. At the first cross-hedge, Bacho and Fulton go forward and lose contact. They later join Arman’s group.

Hill’s four-man group turns west, taking a German prisoner from a nearby field. As they near the exit road, automatic fire comes from the Point. They crawl forward. Hill and Anderson reach a low embankment 8 metres from the road.

They spot a machine-gun position. Hill stands and shouts, “You couldn’t hit a bull in the arse with a bass fiddle!” The gun fires. Hill drops. Anderson tosses a grenade. Hill throws it. The firing ceases. This action clears the way for Lapres’s advancing group. Hill’s men now act as a flank guard for the push south along the road.

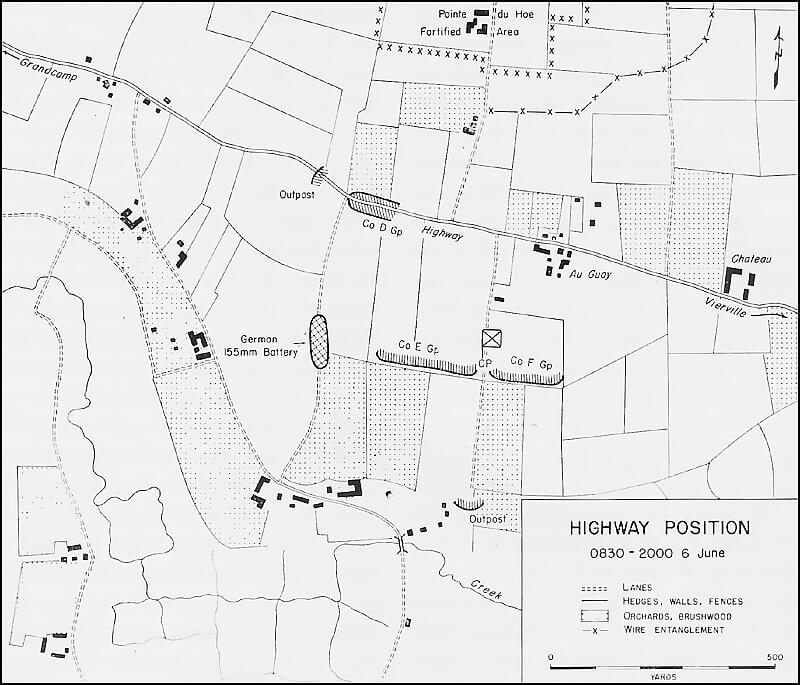

| Holding the Highway and Finding the Guns, June 6th, 1944 |

By 09:00, the Rangers at the road number about 50. All three companies are present. Their mission is to block enemy movement west along the coastal highway. They expect the 116th Infantry Regiment and the 5th Ranger Battalion to arrive soon from Vierville.

Most of the opposition seems to lie west and south. Along the southern side of the highway, narrow fields end at an east-west hedgerow above a shallow valley and stream. The Rangers find prepared foxholes and dugouts along this hedge. Company E and Company F spread out across four fields, flanking a lane that leads south. An outpost moves down to overlook the far side of the valley.

A German dugout near the lane becomes the command post, shared by Lieutenants Arman, Lapres, and Leagans. Enemy contact is minimal, two stragglers are found in the fields.

Company D, about 20 men strong, covers the west. Sergeant Leonard G. Lomell positions men on both sides of the road. A BAR team and six riflemen form a forward outpost. They have good visibility over the valley to Grandcamp. Fields to seaward are thought to be mined, reducing the risk of attack from that direction.

Patrols move out at once. At 09:00, Sergeant Lomell and Staff Sergeant Jack E. Kuhn follow the south lane. About 230 metres from the road, they discover a camouflaged battery of five 155 mm guns, the missing pieces from the Point. Ammunition lies stacked nearby. The guns are aimed toward Utah Beach but could easily be traversed toward Omaha.

No German defenders are present. Lomell disables two guns with thermite grenades, damages a third, and returns for more. Before he gets back, another patrol from Company E, led by Staff Sergeant Frank A. Rupinski, arrives. They finish the job, placing grenades in the barrels and among the charges.

A runner is sent back to Colonel Rudder with news: the primary objective, the battery, has been found and destroyed.

Why the guns are left undefended remains unclear. Some suggest the gunners are caught on the Point and unable to return. Whatever the cause, the battery is rendered useless without a single shot fired. A key threat to both beaches is neutralised, by fewer than a dozen men.

| Multimedia |

| Action on the Left Flank, June 6th, 1944 |

The fighting at Pointe du Hoc on D-Day unfolds in two main parts. One group of Rangers pushes inland to secure the coastal highway. The other remains on or near the fortified ground at the Point. Some stay as planned. Others are forced to remain due to German resistance that revives unexpectedly. This resurgence prevents two boat teams from Company F from advancing. They become locked in actions that hold them near the eastern cliffs throughout the day.

LCA 883 and LCA 884 come ashore well to the left of their intended positions. Lieutenant Wintz, commanding LCA 883, initially believes he is within the fortified area. He assumes the unfamiliar appearance of the ground is due to bombardment. As his first men climb the ropes, he sends them to occupy a ruined hedgerow at the edge of the first inland field. They advance quickly, moving crater to crater without drawing fire. The remainder of the team follows. Meanwhile, men from LCA 884 begin climbing up LCA 883’s ladders. Wintz moves west along the cliffs, searching for Captain Otto Masny, the company commander. Masny, however, has already crossed into the Point and will not be seen again by Wintz that day.

Wintz now realises his position. His men, along with some from LCA 884, are just east of the Point. Shell-torn fields lie to the south, broken only by sparse hedgerows. Occasional artillery and sniper fire from this direction forces the Rangers to ground. One is hit. To the east, a German automatic weapon resumes fire. It fires westward, toward the Point, passing over Wintz’s men. The gun’s location remains unclear.

This enemy weapon, likely a machine gun or light anti-aircraft gun, has disrupted the landings earlier. It is a designated objective for Company F. Wintz decides to neutralise it. He assembles a five-man team. Sergeant Charles Wellage positions his mortar in a crater near the cliff, ready to support the effort. A hedgerow skirts the cliff to the east. Using a drainage ditch on its inland side, the men inch forward, staying low.

Wintz believes this is the first attempt against the gun. In fact, it is the third. Earlier, Private Anderson and two Rangers attempt a similar approach. They fail to find the target and withdraw. Before leaving for the Point, Captain Masny sends out another patrol: First Sergeant Frederick, Staff Sergeant Youso, and Private Kiihnl. They advance one field inland along an east-west hedgerow. Frederick halts to relay an order. The other two press forward. At twenty metres from the suspected position, Youso rises to throw a grenade. A German rifleman shoots him. Kiihnl turns back to locate Frederick. Youso crawls away toward safety. Wintz’s lead element finds him seventy metres on.

Wintz’s group now stretches across two hundred metres of hedgerow. He trails near the rear, with four more riflemen and a mortar observer. Enemy fire begins to sweep an open gap in the hedgerow. One man is hit. The advance slows. Then an order comes from the rear to withdraw.

This message comes from some distance and rests on a misunderstanding. Frederick, ordered earlier to report to Masny, reaches the Number 1 gun position but cannot locate him. There, he hears by word of mouth the instruction to call Wintz back. He relays the message but doubts it. He pushes deeper into the fortified area, finally finding Masny. The captain explains. He thought Wintz was heading south, away from the Point. His order was meant to keep the force in position. He still wants the enemy gun taken out. Frederick dispatches a correction at once, but Wintz has already returned. Two wounded accompany him.

Wintz reorganises. He prepares for a fresh attempt along the cliff. It is the fourth assault on the flanking gun. Just as movement begins, another order halts it. This time the message comes over SCR 300 radio. Rarely do these radios work across the broken terrain. This time, contact succeeds. Colonel Rudder has decided to use naval fire.

Wintz’s men observe from cover. A destroyer closes in. According to their memory, it fires seven salvos. These blasts shear away the cliff’s edge. The fire silences the enemy weapon. However, German snipers still remain east of the Point.

It is now late morning, between 11:00 and 12:00. The eastern threat is gone, but it has taken hours. These events highlight the problem of command and control among scattered Ranger groups. The terrain, communications, and resistance delay coordination. Most of the Rangers from LCA 883 and LCA 884, originally bound for the highway, are now committed east of the Point. Wintz positions them in a right-angled hedgerow formation. It provides a strong anchor against further enemy approach from that direction.

| The Command Post Group, June 6th, 1944 |

As said earlier, Colonel Rudder reaches the top of the cliff at 07:45 and establishes his Command Post in a shell crater. This crater lies between the edge of the cliff and a destroyed German anti-aircraft emplacement. Most of the assault groups have already departed inland. Rudder waits for reports. Visibility is poor in the shattered terrain. Bombardment has turned the area into a maze of craters and wreckage. For the time being, Rudder can exercise little direct control.

German resistance soon begins to revive. Snipers emerge from hidden tunnels and trenches within the fortified zone. Headquarters staff and the last men to climb the cliff are sent out to clear them. These efforts are repeated all day but fail to fully eliminate the threat. The craters and debris offer perfect concealment. Periods of calm alternate with sudden bursts of gunfire. The anti-aircraft position 270 metres west remains active. During one such burst, Colonel Rudder suffers a wound to the thigh.

About thirty minutes after Rudder’s arrival, Sergeant Spleen leads an assault on the western strongpoint. The effort ends in disaster. The position is confirmed as the main centre of resistance. It threatens both the Point and the Rangers now inland. Captain Masny, having helped secure Company F’s flank, joins Rudder at the Command Post. He is assigned to organise perimeter defence using available personnel.

Enemy fire flares up again from the same position. Masny gathers eight men and moves out. They pick up a few more Rangers as they pass through the ruins. A mortar section from LCA 722 joins them. It had originally supported Lieutenant Lapres. With communications severed, it has returned to the Point. Masny’s group also has a .30-calibre machine gun removed from a DUKW.

The party turns west near the exit road and advances about 90 metres. Fire erupts from the left and front. Masny’s men scatter across craters and return fire. The mortar is set up fifty metres behind. As the fight continues, a white flag appears over the German emplacement. Masny’s men remain cautious. Two Rangers near Gun Position 6 rise to investigate. A burst of machine-gun fire kills them both. Artillery now joins the fight. Shells begin falling in adjusted salvos, walking back toward the lane. The lane is bracketed. Masny later calls it “the prettiest fire I ever saw.”

The Rangers are hit hard. Four are killed outright. Nearly all are wounded. Masny, himself wounded in the arm, shouts a general withdrawal. The survivors crawl back under fire. Two more men are shot by snipers. The mortar, now empty, is abandoned. No further attempts are made to storm the anti-aircraft site. Between the two failed assaults, 15 to 20 men are lost.

Naval gunfire tries to help. The destroyer U.S.S. Satterlee opens fire repeatedly but fails to silence the strongpoint. Its position is too far inland to be knocked off by undercutting the cliff. Yet it is too close to the edge for a destroyer to hit directly with its low-angle guns.

Nonetheless, naval support proves vital throughout the day. At 07:28, the Satterlee makes contact with the Naval Shore Fire Control Party. Spotting reports follow. The SCR-284 radio proves unreliable, and signals from the Command Post trigger German artillery. Lieutenant Eikner switches to visual signalling. Signal lamps work well for the rest of the day. Radio fire control resumes in the afternoon. Fire missions include targets at Saint-Pierre, Au Guay, road junctions, and Grandcamp.

By 17:23, the U.S.S. Satterlee has fired 164 salvos and used 70% of her ammunition. She is relieved by U.S.S. Barton and U.S.S. Thompson. The fire control team transmits plans for night fire missions before dark.

Communication with ground forces inland proves difficult. The Signal Operation Instructions are changed before D-Day without informing the Rangers. Eikner manages to reach friendly units but cannot authenticate his messages. Replies never come. Rudder is left unaware of events on Omaha Beach. The navy does not share any updates with the Rangers.

Around midday, Rudder sends a message by all available means. It reads: “Located Pointe du Hoe. Mission accomplished. Need ammunition and reinforcements. Many casualties.” At 15:00, the 116th Infantry Regiment responds but cannot decipher it. It is repeated. Shortly afterwards, a naval relay brings a message from General Huebner: “No reinforcements available.” This is the only communication received from the Point on D-Day by higher command. It raises serious concerns about the Rangers’ situation.

The medical section is fully engaged. Captain Walter Block lands with two enlisted men from LCA 722. Three more medics arrive in other craft. Their packs have ropes attached for quick retrieval under fire. Block carries a mortar shell container filled with medical supplies. All of it reaches the beach safely.

As the Command Post moves to the top of the cliff, one aid man remains with the wounded below. Later, another aid man and Lieutenant Colonel Trevor of the British Commandos assemble a ladder. They mount it against the cliff to evacuate wounded and haul supplies.

By early afternoon, the wounded are becoming a serious concern. At 13:50, Block sends a request via signal light to U.S.S. Barton for a boat to collect casualties. At 14:30, a motorboat and rubber raft attempt a landing. Enemy machine-gun fire from the eastern cliffs hits the boat, wounding one crewman. The landing fails. Some of the most seriously wounded must remain overnight, sheltered in a cave at the base of the cliff.

| German Counterattacks, June 6th, 1944 |

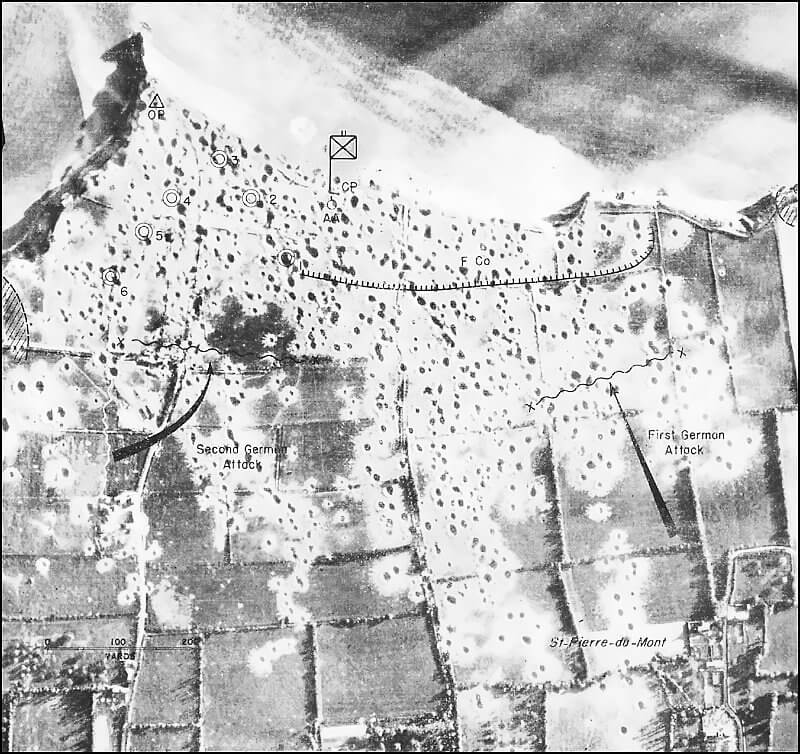

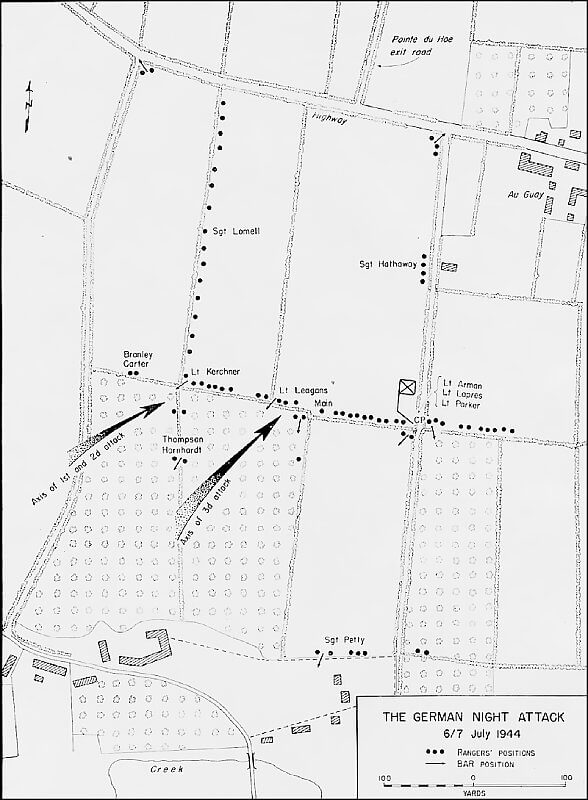

The Germans launch two attacks against the Rangers at Pointe du Hoe during the afternoon. Both efforts strike Lieutenant Wintz’s position from the south and west.

The first assault comes across the open fields leading from Saint-Pierre-du-Mont. Rangers spot German riflemen advancing through bomb craters. At least one German machine-gun team supports the attack. The enemy reaches a hedgerow just one field south of Wintz’s position and sets up the gun. A firefight follows and lasts for nearly an hour. German mortars and artillery join in, but most shells overshoot the Rangers and land near the Point. Company F has a mortar in place but holds fire due to a lack of ammunition. With no BARs on the exposed flank, and naval fire not feasible at such close range, the Rangers hold with disciplined rifle fire. The German effort falters. Gradually, the enemy fire slackens, and the attackers withdraw. Wintz’s men suffer no losses.

A second German assault begins shortly after 16:00. It targets the right flank of Company F’s thin line. This sector contains two BARs and the mortar team, but only a few riflemen. The flank is open toward the German-held antiaircraft position. The enemy pushes up near the exit road before detection. Staff Sergeant Herman Stein and Private Cloise Manning are moving between craters near gun position No. 1 when they see twelve Germans advancing fast from the west. Around the same moment, Staff Sergeant Eugene Elder, manning the mortar, spots more enemy crawling north through the craters.

Stein opens fire at forty metres with his BAR. He wounds two men and disrupts the enemy’s momentum. The Germans falter briefly. When they regroup, their line now stretches beyond Company F’s flank, but their shooting remains inaccurate. Rangers react swiftly. Stein sends word to the mortar crew. Eight riflemen arrive from the left to support the exposed flank.

Sergeant Murrell Stinette helps direct fire. Elder’s mortar fires at a range of around sixty metres. The first rounds strike the forward German elements. They break and retreat. A second burst of shells lands slightly to the south and scatters another enemy party. As they run, BAR fire inflicts more casualties. The mortar continues to fire despite the lack of increments, which were soaked during the landing. Elder adjusts range using elevation and traverse handles.

The second attack collapses. The enemy loses the initiative. Rangers have stopped an assault that threatened to cut off Wintz’s men. The German mortar remains silent throughout. Their machine guns appear briefly but are suppressed by Ranger fire.

Skirmishes continue into the evening. German riflemen probe the fields beyond Wintz’s lines. They appear to test Ranger strength. No further coordinated attacks develop. Near dusk, Wintz pulls his men back toward the Point. He establishes a tighter defensive line. Rangers settle in crater positions close enough to maintain voice contact. Wintz leads a patrol through the Point. They search for German snipers. None are found.

Company F’s men from LCA 883 and LCA 884 began the day with around forty men. By nightfall, they have suffered five killed and ten wounded. Among the dead is Lieutenant Hill. He had reached the highway in the morning with the advance patrols.

Later, Hill attempts to return to the Point. As he and Private Bacho cross fields east of the exit road, they hear German machine-gun fire. They decide to investigate. Hill identifies a gun position two fields east. The two Rangers move toward it.

Bacho scouts ahead and sees a dozen Germans gathered in the corner of a field. Hill chooses to attack. Both men throw grenades over the hedge, then dive into a ditch. The grenades fail to explode. The Germans respond immediately with stick grenades. One lands between the Rangers but causes no harm. A split second later, Hill is shot through the chest.

Bacho responds with more grenades, including one containing thermite. It appears to disorient the Germans. A bullet strikes Bacho’s helmet but does not injure him. He pretends to be dead as the Germans approach. They inspect briefly and leave. Bacho later crawls to a nearby crater. He remains hidden through the afternoon, hearing intermittent fire but seeing no Germans. At nightfall, he returns safely to the Point.

| Afternoon at the Highway Position, June 6th, 1944 |

Throughout the late morning, small groups of Rangers continue to arrive at the forward position inland. By midday, over sixty men now hold the line approximately 800 metres from the Point. Among them are three American paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division. They have been dropped in error near Pointe du Hoe, fifteen miles from their intended landing zone north of Carentan.

The day’s focus is aggressive patrolling. Small combat patrols of six to seven Rangers move along both flanks and into the shallow valley south of the highway. They encounter no major opposition. Several Germans, likely bypassed near the Point, attempt to escape south. Some are killed by Rangers; others are taken prisoner. Patrols round up additional stragglers as the day progresses.

One such encounter occurs around noon. Sergeant Petty returns to the command post to retrieve a rifle for one of his men. At the same time, Sergeant James R. Alexander opens fire with his BAR at two Germans seen entering the lane from the highway. One falls. Petty, Alexander, and three other Rangers move to investigate. As Petty straddles a gate beside the road, a voice shouts “Kamerad” from a nearby ditch. Three Germans emerge, hands raised. Sergeant Walter J. Borowski fires several rounds into the hedgerow in case others are concealed nearby. Two more Germans surrender. A thorough search reveals no further enemy. Two of the prisoners, one a captain, claim they had a machine gun. The Rangers fail to locate it. The prisoners are brought under guard to a field near the Command Post. By afternoon, roughly forty Germans are held in the area.

Sergeant Petty also plays a key role at the southern outpost near the stream valley. With nine Rangers, he commands a BAR team observing the valley floor. Throughout the afternoon, small enemy groups attempt to move west along the rural road toward Grandcamp. These men appear disorganised and do not return fire. Petty uses surprise bursts from his BAR to lethal effect, killing or wounding approximately thirty Germans. Among these are two Polish soldiers from a group of seven, who are fired upon before the Rangers realise they are attempting to surrender.

Late in the afternoon, Ranger patrols observe increased German presence to the south and southwest. However, no signs suggest preparations for a coordinated counterattack. One exception occurs north of the highway, near Company D’s roadblock. At about 16:00, Sergeant Lomell, posted near the Command Post along the junction of the highway and the lane containing the destroyed German battery, notices movement beyond the stone wall. He sees roughly fifty German troops advancing in formation from the direction of the Point. Scouts are deployed forward, and Lomell spots two machine-gun teams and a mortar crew.

There is no time to issue orders or raise the alarm. With only twenty Rangers spread thinly along a 140-metre stretch of road, any engagement would be hopeless. Lomell can only hope the enemy moves past unnoticed. The German column halts just ten metres from the wall. Then, without seeing the Rangers, they turn west and continue parallel to the road. Soon, they cross the tarmac and disappear south into the countryside. The Rangers hold fire. Their discipline saves the position.

Intermittent shellfire continues throughout the day. Most rounds explode harmlessly in trees or fields. One paratrooper is killed after refusing to seek cover in his foxhole. Destroyers offshore maintain regular fire missions inland, directed from observers at the Point. However, communication between the forward highway position and the Point is unreliable. With no Naval Shore Fire Control Party present at the highway, corrections are difficult. Runners face sniper fire along the route. Several Rangers must fight their way through in both directions. Lieutenant Lapres attempts to reach Colonel Rudder’s Command Post twice. On his first trip, he brings back ammunition and a radio, which fails to function. On his second attempt, Lapres is turned back by German infiltrators who have cut the route between the highway and the Point.

A platoon of company A, 5th Ranger Battalion landing at Omaha Beach, manages to reach Pointe du Hoc. A group of twenty-three men under First Lieutenant Parker. At 08:15, Parker’s platoon becomes separated from the 5th Ranger Battalion during the initial assault between Vierville and Saint-Laurent. Unaware that the main force is engaged inland, Parker moves his men south of Vierville to the designated assembly area. Departing Château de Vaumicel at 14:30, they eliminate a small enemy strongpoint, capturing twelve prisoners. Finding their assembly area deserted, Parker’s men continue towards Pointe du Hoc, avoiding main roads. Approaching from the south, the platoon encounters fierce enemy fire and narrowly avoids encirclement, forcing a brief retreat. The Rangers then move cross-country, finally joining defensive positions of the 2nd Ranger Battalion south of the Grandcamp-Vierville road at around 21:00. Still believing the 5th Ranger Battalion close behind, they inform Colonel Rudder accordingly.

| Twilight and Command Decision, June 6th, 1944 |