| Page Created |

| August 16th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| October 24th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Poland |

|

| The United States |

|

| Operation Market Garden |

| 1st Airborne Division 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade 82nd Airborne Division 101st Airborne Division XXX Corps |

| Other Units Involved |

| 1st Airborne Division 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade 82nd Airborne Division 101st Airborne Division |

| September 17th, 1944 – September 26th, 1944 |

| Operation Market Garden |

| Objectives |

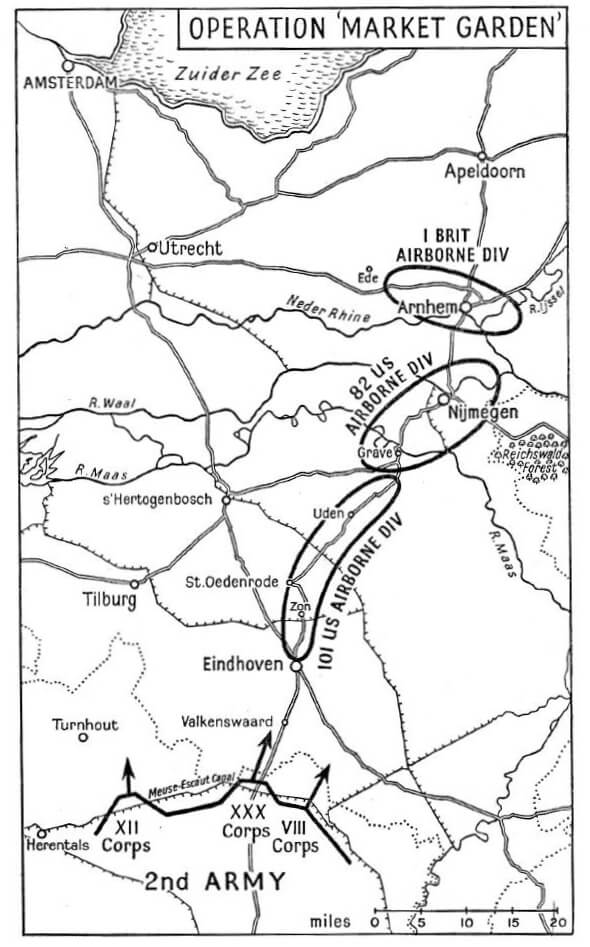

- Airborne forces capture key bridges and terrain in the Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem area under the tactical command of I Airborne Corps, headed by Lieutenant General Frederick Browning.

- Ground Forces spearheaded by XXX Corps under Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, are to advance north and link up with the airborne forces and relieve them

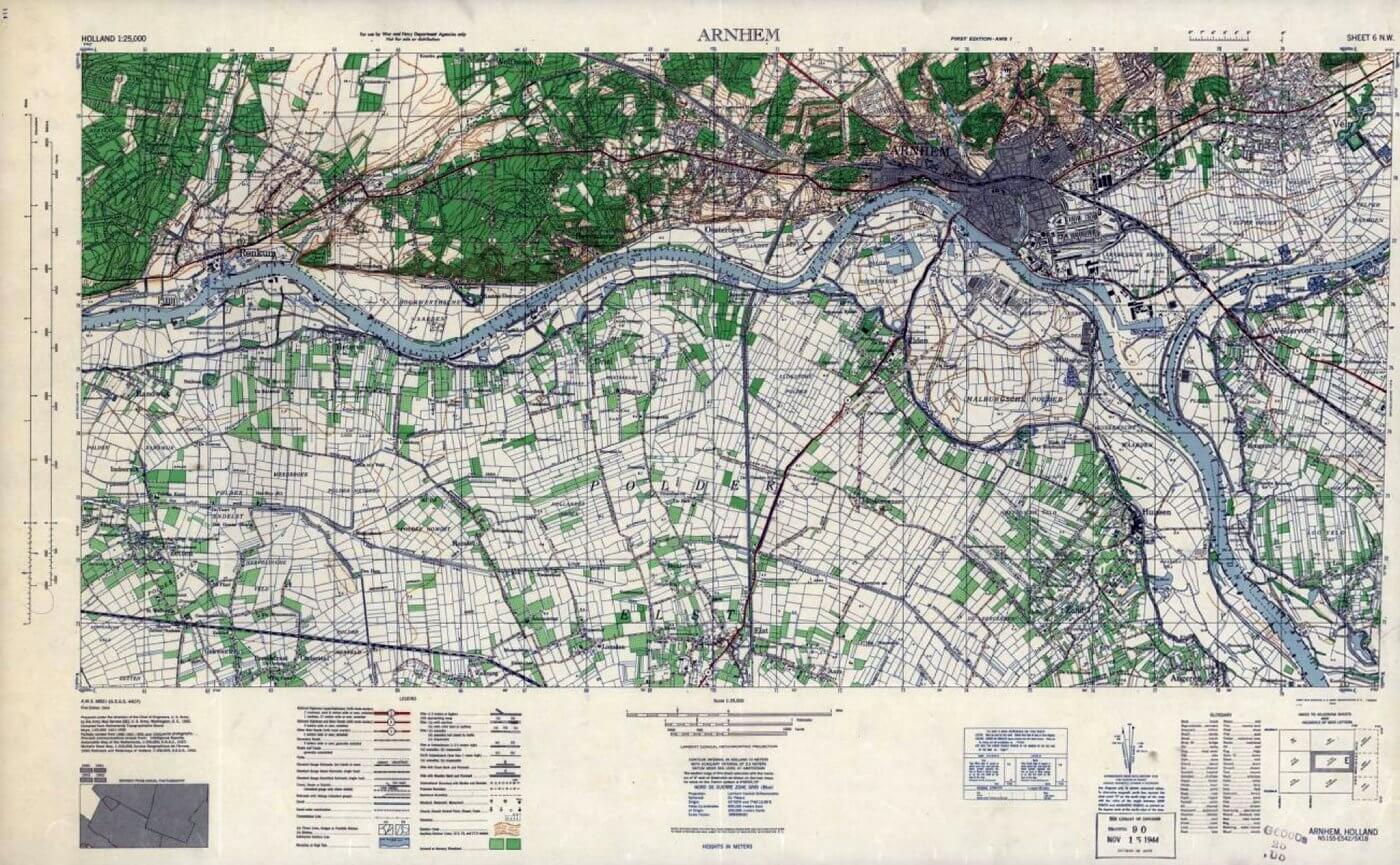

| Operational Area |

- Eindhoven area, The Netherlands

- Nijmegen area, The Netherlands

- Arnhem area, The Netherlands

- Highway 69 “Hell’s Highway”, The Netherlands

| Allied Forces |

- First Allied Airborne Army

- 1st Airborne Division

- 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- 52nd, Airlanding Division

- 82nd Airborne Division

- 101st Airborne Division

- XXX Corps

- Guards Armoured Division

- 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division

- 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division (Reserve)

- 8th Armoured Brigade

- Prinses Irene Brigade

| Axis Forces |

- II SS-Panzer-Corps

- 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen”

- 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg”

- 6. Fallschirmjäger Regiment

- Bataillon I, Hauptmann Emil Priekschat

- Bataillon II, Hauptmann Rolf Mager

- Bataillon III, Hauptmann Horst Trebes

- Pionier Kompanie

- Panzerjäger Kompanie

- Fusilier Kompanie

- Kampfgruppe von Tettau

- Feldkommandantur 642

- SS-Unterführerschule Arnheim

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Polizei Schule

- SS-Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 4

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- SS-Wach Battalion 3

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 10

- Schiffsturm Abteilung 6/14

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 2

- Fliegerhorst Battalion 3

- Artillerie Regiment 184

- Sicherheit Regiment 42

- Kampfgruppe Knoche

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- MG Bataillon 30

- FlaK Abteilung 688

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Bataillon I

- Panzer Abteilung 224

- SS Ersatz Abteilung 4

- Deelen Airfield FlaK Kompanie

- Wach Kompanie

- Reichs AD

- Hermann Göering Schule Regiment

- Sicherheit Regiment 26

- Kampfgruppe Kraft

- SS-Panzer Grenadier Ausbildungs und Ersatz Bataillon 16

- Schwerepanzer Abteilung 506

- Schwerepanzer Kompanie Hummel

- StuG Abteilung 280

- Artillerie Regiment 191

- Bataillon I

- Bataillon II

- Bataillon III

- SS-Werfer Abteilung 102, Hauptsturmfürer Nickmann

- Kampfgruppe Brinkmann

- Kampfgruppe Bruhn

- Kampfgruppe Harder

- Sperrverband Harzer

- MG Bataillon 47

- Marine Kampfgruppe 642

- Kampfgruppe Schörken

- Kampfgruppe Kauer

- SS-Abteilung “Landstrum Nederland”

- Kampfgruppe Knaust

- Ersatz Abteilung Bocholt

- Panzer Kompanie Mielke

- Kampfgruppe Spindler

- FlaK Abteilung Swoboda

- Kampfgruppe von Allworden

- Kampfgruppe Weber

| Operation |

In August 1944, following the successful Allied breakout from Normandy and the encirclement of German forces in the Falaise Pocket, the Allied armies aggressively pursue the retreating German forces, driving them out of most of France and Belgium. As the Allied forces rapidly advance and capture Belgium within days, it seems inevitable that the liberation of the Netherlands is just a matter of time. On September 4th, 1944, the Dutch Prime Minister Gerbrandy in exile in Great Britain announces that Allied troops have crossed the Dutch border. The BBC even reports that the Dutch city of Breda has already been liberated. This news sparks widespread jubilation throughout the Netherlands, though the rumours vary from city to city. In Rotterdam, people believe that Canadian troops have already reached Moerdijk, while in Amsterdam, there are claims that Rotterdam and The Hague have been freed.

Amidst this euphoria, the German Reich Commissioner, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, issues an order on September 2nd, 1944 for all German civilians in the Netherlands to evacuate to the eastern part of the country. He takes up residence in a bunker in Apeldoorn, while Anton Mussert, the leader of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (National Socialist Movement), advises his party members to also flee eastward.

Initially, the German evacuation proceeds in an orderly fashion. However, following the fall of Antwerp on September 4th, 1944, and a proclamation by the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina in exile in Great Britain, panic sets in. Large numbers of Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging members gather at train stations, desperate to flee to the eastern Netherlands or even to Germany. German soldiers desert in large numbers, also attempting to escape eastward.

As the Dutch sense that the end of the war is near, they begin to prepare for liberation. In the south, the sound of artillery fire has been heard for days, and everyone is anxiously awaiting the arrival of the first Allied troops. Orange ribbons and Dutch flags are displayed, but the anticipated troops do not arrive. It soon becomes clear to the resistance that Breda has not been liberated, and the British have not even crossed the border. This realisation leads to growing concern, and they hope that the Allies will launch an attack soon, especially as the Germans are in disarray.

| Germans Back in Control |

On September 4th, 1944, Hitler relieves Field Marshal Walter Model of his temporary command in the west, replacing him with Gerd von Rundstedt. However, Model remains the commander of Army Group B. Despite his experience, Model is dissatisfied with his dual role, preferring to be at the front with his troops rather than dealing with the administrative burdens of overall command.

Model faces a dire strategic situation, as his forces have been split in two by the advancing Allies. The 15. Armee, under General Gustav-Adolf von Zangen, is trapped south of the Westerschelde after retreating from the coast and is attempting to escape to North Brabant via Walcheren and Zuid-Beveland. Meanwhile, the 7. Armee has been pushed back by American forces to Aachen and Maastricht. A 120-kilometres gap now exists between these two armies, with no functioning combat units remaining, only scattered groups of German soldiers fleeing north and east. Model fears that the British 2nd Army, positioned at the Dutch border, will exploit this gap. On September 4th, 1944, nothing could have prevented the British from occupying the entire area up to the Maas. Known for his ability to improvise defences on the Eastern Front, Model now faces the daunting task of halting this chaotic retreat. He issues an order to stop the withdrawal, but it reaches only a few.

Lieutenant General Kurt Chill receives Model’s order. Having lost almost the entire 85. Infantrie Division in the fighting, Chill is ordered to regroup the remnants and retreat to Germany. However, upon witnessing the chaotic retreat and reading Model’s directive, Chill decides to ignore his original orders. After gathering his troops, he orders them to dig in along the Albert Canal and places officers at the bridges to stop the fleeing soldiers. Troops ranging from artillerymen to cooks are now repurposed to defend the Albert Canal. Chill’s actions help stabilize the situation in this area, and similar measures are taken across the entire western front. By the second and third weeks of September, over 150,000 German soldiers who had fled are recaptured and reintegrated into the military structure.

Also on September 4th, 1944, Hitler orders General Kurt Student to form the 1. Fallschirm-Armee to close the gap between Antwerp and Maastricht. Student is given 4,000 trained Fallschirmjäger but must also rely on older, inexperienced men, unemployed Luftwaffe personnel, sailors, and anti-aircraft gunners. He also receives twenty-five pieces of mechanised artillery. Student immediately sends his paratroopers ahead, and within twenty-four hours, they reach the Albert Canal. Upon surveying the area, Student realises that Chill has performed a near-miracle in stabilising the front. Student establishes his headquarters in Vught, Noord Brabant, commanding not only the 85. Infantrie Division but also the 7. Fallschirmjäger Division, the 719. Infantrie Division, and the 176. Infantrie Division.

Student’s army receives unexpected reinforcement when Von Zangen successfully leads the 15. Armee across the Westerschelde using various vessels, advancing through Zuid-Beveland into North Brabant. The gap between Model’s two armies begins to close, resolving one of his most pressing problems.

Despite these efforts, the defence of the Albert Canal remains weak. On September 6th, 1944, the Guards Armoured Division captures a bridge at Beringen, and despite a counterattack by several Jagdpanthers during the Battle of Hechtel, the division advances towards Neerpelt, just south of the Dutch border near Eindhoven. On September 10th, 1944, the Irish Guards seize Joe’s Bridge over the Bocholt-Herentals Canal intact. Model does not anticipate any airborne landings, and coincidentally sets up his headquarters in Oosterbeek. Similarly, two SS Panzer divisions, the 9. SS-Panzerdivision “Hohenstaufen” and the 10. SS-Panzerdivision “Frundsberg” of the II SS-Panzer-Corps which escaped France, are stationed in the Veluwe region. Although these divisions are spotted by Allied reconnaissance, their presence is underestimated, and Browning does not even inform the airborne divisions, as the SS units have clearly suffered heavy losses, leaving them with only three deployable tanks between them.

| Logistics |

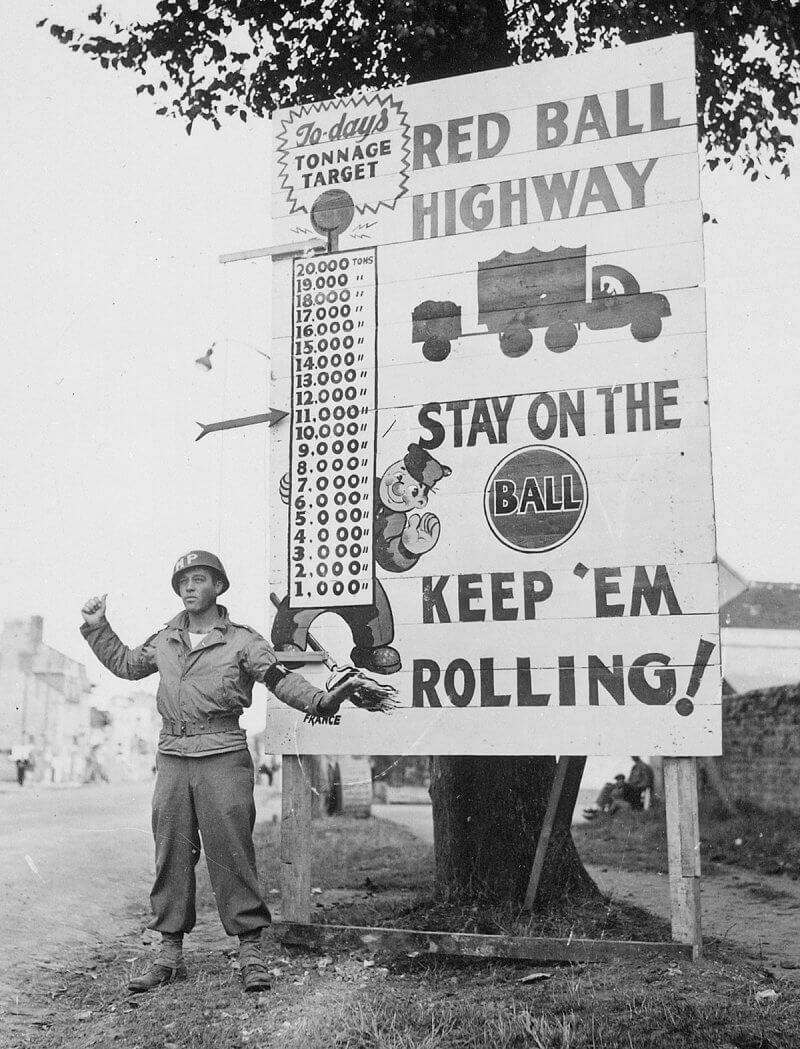

Unknown to the Germans, by late August, the Allied advance is hampered by a severe shortage of gasoline, forcing several divisions to pause and resupply. Eisenhower faces the daunting task of managing the logistical demands of the various Allied armies. While fuel supplies are available in the improvised ports of Normandy, the challenge lies in transporting them across the long distances to the front lines in Belgium and northern France. This fuel is transported in five-gallon jerry cans, hauled by trucks from Normandy in an operation known as the Red Ball Express. The solution to these logistical difficulties appears to be the capture of a major port closer to the advancing armies.

On September 4th, 1944, Field Marshal Montgomery’s forces successfully capture the port of Antwerp in Belgium almost intact, but the Scheldt Estuary, leading to the port, remains under German control. Despite the strategic importance of Antwerp, neither Eisenhower nor Montgomery initially prioritises opening the port, delaying its use by Allied supply ships until November 28th, 1944, after the Battle of the Scheldt.

| Strategies |

General Eisenhower advocates for a “broad front strategy,” wherein Montgomery’s forces in Belgium and general Bradley’s forces in France advance simultaneously along a wide front into Germany. Montgomery and General George S. Patton, Bradley’s aggressive subordinate, both favor a concentrated “single thrust” into Germany, but each wants to lead it. Montgomery argues that a focused and powerful drive across the Rhine into Germany’s heart, supported by all available Allied resources, is the best strategy. This would, however, reduce Bradley’s American forces to a more static role. Patton, on the other hand, asserts that with enough gasoline, he could be in Germany within days. However, war planners find both proposals tactically and logistically unrealistic.

Although Eisenhower agrees that Montgomery’s advance towards the Ruhr should take precedence, he insists that it is also important to keep Patton advancing. Montgomery counters that with the deteriorating supply situation, he cannot reach the Ruhr unless all resources are concentrated on one thrust, preferably towards Berlin. Initially, Montgomery proposes Operation Comet, a limited airborne operation aimed at capturing bridges on the way to the Rhine, but poor weather and increased German resistance force him to cancel the plan by September 10th, 1944. Operation Comet is in the line of many planned airborne operations before. Between June 1944 and Market Garden at least 15 airborne operations were planned.

- Operation Comet

- Operation Tuxedo

- Operation Wastage

- Reinforcement of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division June 7th, 1944 to June 10th, 1944

- Operation Wild Oats

- Operation Beneficiary

- Operation Swordhilt

- Operation Hands-Up

- Operation Transfigure

- Operation Boxer

- Operation Axehead

- Operation Linnet

- Operation Linnet II

- Operation Infatuate

- Operation Comet

Most of them became unnecessary simply because the fast Allied advance had already passed the traget area for the planned airborne operation.

| Operation Market Garden |

Field Marshal Montgomery then devises Operation Market Garden, a more ambitious plan to bypass the German West Wall defences by securing a crossing over the Rhine River and advancing towards the Ruhr. The operation is also driven by the need to neutralise V-2 rocket sites in the Netherlands that are launching attacks on London. On September 10th, 1944, despite doubts from the British Second Army commander, Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey, Montgomery insists on proceeding with the plan after receiving orders from the British government to eliminate the V-2 launch sites.

Frustrated by Eisenhower’s hesitation to give Market Garden the priority he desires, Montgomery flies to Brussels to confront him. During a heated meeting, Montgomery dramatically destroys a file of Eisenhower’s messages and demands a concentrated northern thrust and priority for supplies. Eisenhower, maintaining his composure, rebukes Montgomery, reminding him of his subordinate role, but ultimately agrees to give Operation Market Garden “limited priority” within the broader strategy.

Eisenhower, under pressure from the United States to deploy the First Allied Airborne Army, sees Operation Market Garden as an opportunity to push the Allies across the Rhine. The airborne forces, which have been pulled back from the frontline, include three British and three U.S. divisions, along with the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade. After several proposed operations are canceled due to the rapid Allied advance, Eisenhower believes that Operation Market Garden could provide the necessary impetus for crossing the Rhine.

On September 10th, 1944, General Eisenhower directs Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton, the commander of the First Allied Airborne Army to plan a new and ambitious operation, which will be known as Operation Market Garden. Brereton is now charged with devising a larger airborne assault, designated as Operation Market, to be coordinated with a simultaneous ground offensive called Operation Garden. The overarching goal of Operation Market Garden is to secure a bridgehead across the Rhine River at Arnhem.

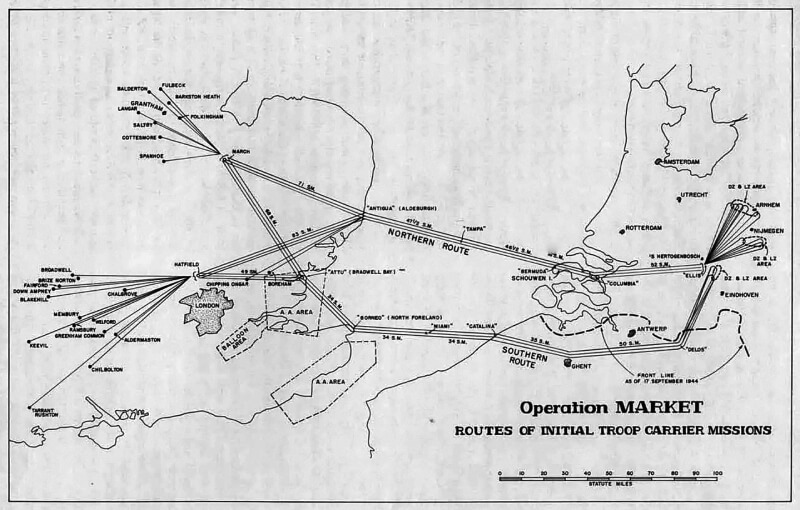

The proposed date for the operation, depending on favorable weather conditions, is set for 14 September. Given the limited time available, Brereton decides to adapt the plans from a previously cancelled airborne operation, Operation Linnet I and II, to suit the new objectives.

In preparing for this massive operation, Brereton makes several crucial adjustments to the original Operation Linnet plan. He decides to restrict glider missions to “single-tows,” where each tug aircraft is responsible for towing only one glider. The Operation Linnet plan envisioned a more complex double-tow mission. However, due to a combination of poor weather, the extensive resupply missions required for the advancing Allied armies, and a lack of training opportunities in August for the IX Troop Carrier Command, Brereton judges that attempting double-tows without adequate practice would be too risky.

Brereton also decides that the operation will be conducted in daylight, leveraging the extensive air support planned from both the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Air Force. This decision is intended to avoid the dispersal problems experienced during the British and American airborne landings in Normandy earlier in June. As weather and logistical delays push the start date to September 17th, 1944, Brereton finalises his plan to take advantage of the dark moon on that date, minimizing the risk of detection by enemy forces.

However, with daylight hours already shortening in September, Brereton decides against authorizing two lifts per day. Consequently, due to the limited number of available troop carrier aircraft, the airborne phase of Operation Market will require three consecutive days to fully deploy all forces into The Netherlands. This cautious approach reflects Brereton’s strategy to balance operational effectiveness with the safety of his troops, ensuring that the complex and high-stakes mission proceeds as smoothly as possible.

The plan, now finalised, consists of two main operations:

- Market: The airborne component, led by Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton’s First Allied Airborne Army, aims to capture key bridges and terrain under the tactical command of I Airborne Corps, headed by Lieutenant General Frederick Browning.

- Garden: The ground forces of the British Second Army, spearheaded by XXX Corps under Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, are to advance north and link up with the airborne troops

| Operation Market |

Operation Market involves the deployment of four airborne units from the First Allied Airborne Army. The First Allied Airborne Army is established on August 2nd, 1944, following an order from General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. This formation is designed to unify and command all Allied airborne forces in Western Europe, operating under the Allied Expeditionary Force from August 1944 until the end of the war in May 1945.

The First Allied Airborne Army encompasses a broad array of units, including all British airborne forces, which includes the 1st Airborne Division, 6th Airborne Division, the 52nd Airlanding Division as well as the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. As well as the U.S. IX Troop Carrier Command and the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps, which oversees the 17th Airborne Division, the 82nd Airborne Division, and the 101st Airborne Division, along with several independent airborne units. Additionally, the formation controls This structure ensures a coordinated effort among the various Allied airborne divisions during key operations in Western Europe. The British strongly suggest that a British officer, specifically Lieutenant General Frederick Browning, be appointed as its commander.

However, since the majority of the troops and aircraft are American, Eisenhower appoints U.S. Army Air Forces officer Lieutenant General Lewis Hyde Brereton to command the First Allied Airborne Army on July 16th, 1944, with his official appointment confirmed by Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force on August 2th, 1944. Despite his lack of experience in airborne operations, Brereton brings extensive command experience, most recently as commander of the Ninth Air Force, providing him with crucial operational knowledge of IX Troop Carrier Command. For Operation Market Garden, five airborne units of the First Allied Airborne Army are assigned to three different areas, Eindhoven Nijmegen and Arnhem.

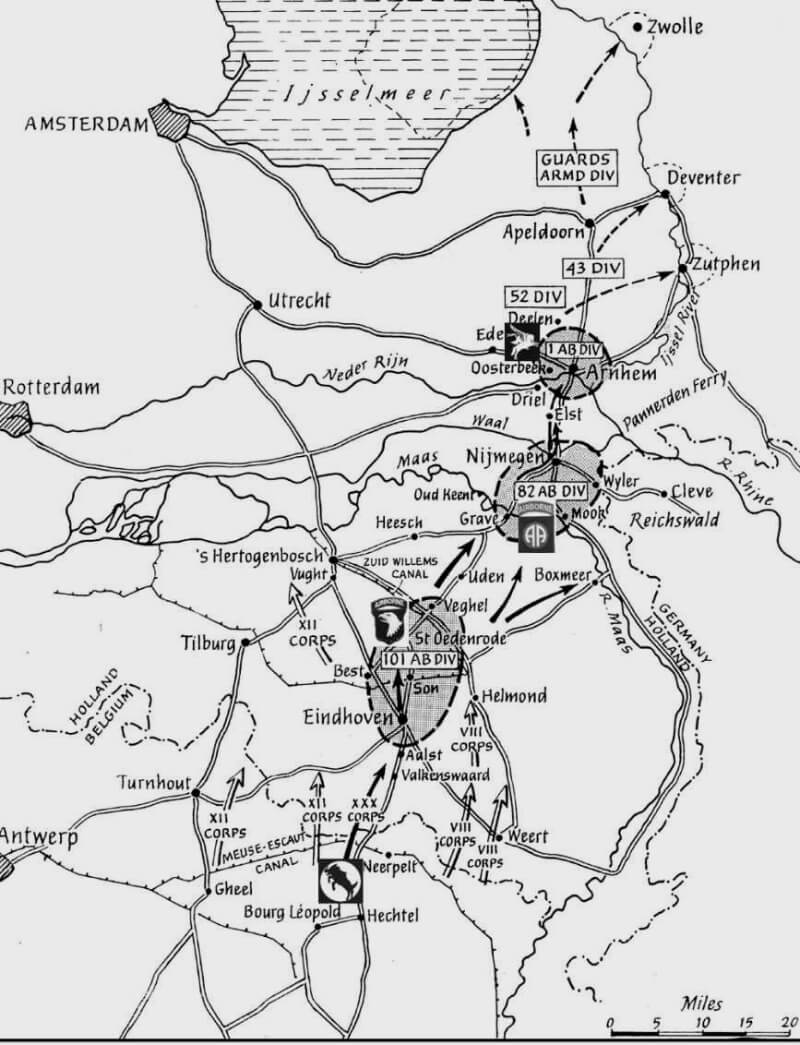

The 101st Airborne Division of the United States, known as the “Screaming Eagles” and led by Major General Maxwell D. Taylor, is tasked with securing the area around Eindhoven. The planned drop zones for the division are strategically located in Best, Son, Sint-Oedenrode, and Veghel. Their mission is to capture key bridges: the bridge over the River Aa and the Zuid-Willemsvaart Canal at Veghel, the bridge over the Dommel River at Sint-Oedenrode, and the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal at Son. After successfully securing these bridges, the division is to advance towards Eindhoven, where they are expected to link up with the advancing ground forces of the 30th Corps.

The 82nd Airborne Division, also from the United States and known as the “All American” division, is under the command of Brigadier General James Gavin. This division is assigned the area around Nijmegen, with designated drop zones in Groesbeek, Overasselt, and Grave. The division’s primary objectives include securing the high ground around Groesbeek, which is vital for controlling the surrounding area, and capturing several key bridges: those over the Waal River at Nijmegen, the Maas River at Grave, and at least one bridge over the Maas-Waal Canal. The Waal Bridge at Nijmegen, however, is initially given lower priority, leading to its capture only after several days of intense combat. The high ground at Groesbeek is particularly important because it dominates the Reichswald, an alternative route that bypasses the northern end of the Westwall.

The British 1st Airborne Division, commanded by Major General Roy Urquhart, is responsible for the operation near Arnhem. The division plans to land in drop zones at Wolfheze, Oosterbeek, and Ede. Their crucial task is to capture the road bridge in Arnhem and hold it for a minimum of 48 hours, awaiting reinforcements from the south. The division is supported by the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, under the command of Major General Stanisław Sosabowski, which is scheduled to be dropped south of the road bridge after the initial landings. Once contact is made with the advancing ground forces, the plan is to secure Deelen Airfield on the Veluwe, where the 52nd Airlanding Division will subsequently be deployed. The 52nd Airlanding Division is planned to land on the fourth day of Operation Market.

Initially known as the 52nd “Lowland” Infantry Division, the division is trained for mountain warfare, with the expectation of participating in a proposed invasion of Norway. However, this operation never materialises, and the division is not deployed in this capacity. Following June 1944, the 52nd Airlanding Division undergoes a significant reorganisation and is retrained for airlanding operations. In its new role, the division is transferred to the First Allied Airborne Army. By this time, the division is under the command of Major-General Edmund Hakewill-Smith, who leads the unit through its transition and preparation for its new responsibilities in the Allied airborne forces.

Lieutenant General Frederick Browning, commander of the 1st Airborne Corps, establishes his headquarters near Groesbeek to oversee the operation. Browning, eager to bring his entire staff, plans to establish a field headquarters during the operation, using 32 Airspeed Horsa gliders for administrative personnel and six Waco CG-4A gliders for U.S. Signals personnel. Taking up a huge amount of essential glider capacity.

Operation Market is the largest airborne operation in history, involving the deployment of over 34,600 troops from the 101st Airborne Division, the 82nd Airborne Division, and 1st Airborne Division, along with the Polish Brigade. Of these, 14,589 troops land by glider, while 20,011 arrive by parachute. The gliders also deliver 1,736 vehicles, 263 artillery pieces, and 3,342 tons of ammunition and supplies.

To transport these 36 battalions of airborne infantry and their support troops to the continent, the First Allied Airborne Army has operational control of the 14 groups of IX Troop Carrier Command, and from September 11th, 1944, it also receives support from 16 squadrons of 38 Group Royal Air Force and a transport formation, 46 Group. The combined force includes 1,438 C-47/Dakota transports (1,274 from the United States of America Air Force and 164 from the Royal Air Force) and 321 converted Royal Air Force bombers. The Allied glider force, significantly rebuilt after Normandy, now numbers 2,160 CG-4A Waco gliders, 916 Airspeed Horsa’s (812 Royal Air Force and 104 United States Army), and 64 General Aircraft Hamilcars. However, due to a shortage of pilots, U.S. gliders fly without co-pilots, carrying an extra passenger instead.

Given the dual roles of the C-47’s as paratrooper transports and glider tugs, and because IX Troop Carrier Command provides all transport for both British parachute brigades, the force can only deliver 60 percent of the ground troops in a single lift. Consequently, the troop-lift schedule is split over successive days. On the first day, 90 percent of the United States of America Air Force transports drop paratroopers, with the same proportion towing gliders on the second day, while Royal Air Force transports are almost exclusively used for glider operations. Despite the capability to conduct two airlifts on the first day, Brereton decides against it, citing the need for a half-day bombardment of German flak positions and a favorable weather forecast predicting clear skies for four days.

The operation begins on September 17th, 1944 under a dark moon. Allied airborne doctrine prohibits large-scale operations without sufficient light, so the mission is executed in daylight. The risk of Luftwaffe interception is deemed low due to Allied air superiority, but concerns persist regarding the increasing number of German flak units, particularly around Arnhem. Brereton, confident in the ability of Allied tactical air operations to suppress flak, orders the mission to proceed.

Daylight operations, as demonstrated in the invasions of Sicily and Normandy, offer significant advantages, including improved navigational accuracy and the ability to compress successive waves of aircraft, tripling the number of troops delivered per hour. Additionally, the time required for airborne units to assemble on the drop zone is reduced by two-thirds. However, the dual tasks of towing gliders and dropping paratroopers cannot be performed simultaneously, so Brereton’s staff schedules only one lift on the first day, focusing on flak suppression and relying on a weather forecast that soon proves inaccurate. With only a week of intense preparations, Operation Market is launched.

| Operation Garden |

Operation Garden, the ground component, is led by XXX Corps, under the command of Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, is positioned near Leopoldsburg. The Corps is spearheaded by the Guards Armoured Division, with the 43rd Wessex Infantry Division and the 50th Northumbrian Infantry Division held in reserve. The British 8th Armoured Brigade and the Dutch Prinses Irene Brigade are integral to the ongoing operation. As of September 16th, 1944, the Guards Armoured Division commands a formidable tank force, consisting of 276 tanks. This includes 175 Shermans, with thirty-seven equipped as “Fireflys,” forty Stuarts, fifty-eight Cromwells, and three Challengers.

The operation requires the corps to break out from the bridgehead over the Maas-Scheldt Canal, advancing through Joe’s Bridge at Lommel. Their route follows the path cleared by airborne forces, moving through key locations including Eindhoven, Sint-Oedenrode, Veghel, Uden, Grave, Nijmegen, and finally Arnhem. The timeline for this advance is precise: by 17:00 on the first day, they are expected to reach Eindhoven, followed by Veghel at midnight. On the second day, the objective is to reach Grave by 12:00 and Nijmegen by 18:00. By 15:00 on the third day, they aim to arrive in Arnhem. So, the plan expects XXX Corps to reach the 101st Airborne Division’s area by the end of the first day, the 82nd Airborne Division’s area by the second day, and the 1st Airborne Division’s area by the fourth day at the latest. Once achieved, the airborne divisions would join XXX Corps in breaking out from the Arnhem bridgehead.

Upon securing Arnhem, the corps must push forward towards the IJsselmeer, specifically targeting the area around Nunspeet. The strategic goal is to cut off German forces in the Western Netherlands. Following this, the 43rd Infantry Division is tasked with establishing bridgeheads over the IJssel River at Doesburg, Zutphen, and Deventer, enabling a direct advance into the Ruhr area, a crucial objective within Germany.

XXX Corps faces six major water obstacles along the route from their jumping-off point to the objective on the north bank of the Lower Rhine River. These obstacles include the Wilhelmina Canal at Son en Breugel, the Zuid-Willems Canal at Veghel, the Maas River at Grave, the Maas-Waal Canal, the Waal River at Nijmegen, and finally, the Rhine at Arnhem. The plan hinges on the airborne forces capturing the bridges over these obstacles almost simultaneously. Any failure to secure these bridges would result in significant delays or potentially catastrophic defeat. Anticipating the possibility of the Germans demolishing the bridges, XXX Corps prepares extensive contingency plans. This includes amassing a vast quantity of bridging materials, 2,300 vehicles to transport them, and deploying 9,000 engineers ready to reconstruct the bridges if necessary.

Highway 69, later known as “Hell’s Highway,” serves as the critical route for the planned advance during Operation Market Garden. This road is a narrow two-lane highway, partially elevated above the flat polder and floodplain terrain surrounding it. The soft ground on either side makes it difficult, if not impossible, for tactical vehicles to maneuvre off the road. The landscape is dotted with dikes and drainage ditches, while dikes themselves are often lined with trees or large bushes, and the roads and paths are similarly bordered by trees. In early autumn, these natural features severely restrict visibility, posing significant challenges for the advancing forces.

Although the area is predominantly flat, with less than 9 metres of variation in elevation, Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks, commander of XXX Corps, notes the challenges presented by the terrain. He describes the country as “wooded and rather marshy,” making any attempts at outflanking maneuvers virtually impossible. Two key high ground areas, both reaching heights of 90 metres, are strategically crucial. One is located northwest of Arnhem, and the other is the Groesbeek ridge in the 82nd Airborne Division’s sector. Securing these elevated positions is essential for holding the highway bridges, which are vital to the success of the entire operation.

The operation assumes that German resistance has largely collapsed, with the German Fifteenth Army in retreat from Canadian forces and believed to have no significant armored units available. The Allied command expects XXX Corps to encounter limited resistance along Highway 69, with the German defenders spread thin over a 100-kilometres front as they attempt to contain the scattered airborne landings from the Second Army in the south to Arnhem in the north.

| Multimedia |