| Length |

| 11,24 metres |

| Wingspan |

| 21,98 metres |

| Height |

| 2,74 metres |

| Weight |

| 860 kilograms |

| Load |

| 1 Pilot 9 fully armed soldiers 1.200 kilograms load total 2.100 kilograms take-off weight |

| Propulsion |

| – |

| Armour |

| – |

| Armament |

| MG 15 MG 34 |

| DFS 230, Lastensegelflugzeug |

| Podcast |

| Introduction |

Germany’s interest in military gliders develops from post-World War 1 restrictions and a strong national gliding culture. After the First World War, the Treaty of Versailles bans Germany from developing powered aircraft. Engineers and pilots therefore concentrate on unpowered flight. Civilian gliding clubs expand rapidly and become centres of aerodynamic research. By the early 1930’s, German designers experiment with large sailplanes for scientific and meteorological work. Alexander Lippisch and Walter Georgii contribute to advanced projects, including the Obs glider of 1932.

These developments attract attention from the new political leadership. In 1934, Adolf Hitler inspects a large glider during a demonstration. He recognises its potential for silent troop delivery behind enemy lines. At the same time, Germany rebuilds its air arm in secrecy. By 1936, the Luftwaffe trains airborne troops designated as Fallschirmjäger. Early planning exposes weaknesses in parachute assaults. Paratroopers land dispersed and remain vulnerable while assembling. Senior commanders therefore seek a method for concentrated landings. Kurt Student supports the use of assault gliders as a practical solution.

In 1937, the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug produces a purpose-built assault glider prototype. The programme operates under chief designer Hans Jacobs. His team works at Darmstadt on a compact aircraft capable of carrying an infantry squad. Design work begins in October 1936. Exactly one year later, the first prototype, designated DFS 230 V1, is completed. Flight trials begin during 1937. Hanna Reitsch conducts the initial test programme and demonstrates the aircraft’s handling and landing precision.

The DFS 230 is initially presented as a low-cost meteorological glider. A demonstration for senior Luftwaffe officers reveals its true military value. The aircraft proves capable of silently delivering armed troops to a precise objective. The Luftwaffe immediately authorises series production. This decision leads to the creation of the world’s first operational assault glider.

Throughout development, the design objective remains consistent. The DFS 230 carries nine fully equipped soldiers and a pilot. It lands silently on a precisely chosen objective. No powered transport of the period offers comparable surprise. This compact assault glider concept influences later designs adopted by other nations.

| Multimedia |

| History |

In 1922, Hermann Göring holds a private conversation with American Captain Edward “Eddie” Rickenbacker, the celebrated First World War fighter ace. Göring tells him that Germany’s future will be decided in the air. Air power, he says, will be the means by which German strength is restored. He lays out a three-stage plan. First, Germany will teach gliding as a sport to its young men. Second, it will build up commercial aviation. Third, it will create the framework of a military air force. When the moment is right, Göring predicts, all three strands will be brought together and Germany will be reborn.

Gliding subsequently becomes an important element of German rearmament. It provides a means to train thousands of glider pilots, from whom the Luftwaffe later draws many of its future aircrew.

Between 1930 and 1933, new directions emerge in German glider development. A decision is taken to design a larger sport glider intended to carry a meteorological laboratory, with scientists and technicians operating instruments during flight.

The design and development of this unusual aircraft take place at the Rhön-Rossitten Research Institute in Munich. The project involves leading German specialists, including the well-known engineer and glider designer Alexander Lippisch. It brings together expertise from both the sport glider world and the broader aircraft industry.

By 1933, the work produces a completely new type of aircraft that breaks with established sport glider design. The new machine has a much larger fuselage, intended to carry heavy loads. Its wings are strengthened to support additional weight. The long, elegant wings typical of sport gliders are replaced by shorter, thicker ones. The resulting wing form resembles that of powered aircraft more than that of a sailplane.

In appearance, the aircraft looks like a transport aeroplane without an engine. After take-off it must be towed by a powered aircraft, then released within gliding distance of its landing area, descending steadily to the ground.

As a rule, it cannot maintain altitude by exploiting air currents like a true sport glider. Its weight and design commit it to a continuous descent, leaving little scope for soaring.

When lightly loaded, however, many pilots report that it handles much like a conventional glider. Under favourable conditions, some manage to exploit air currents and achieve brief periods of soaring.

For high-altitude meteorological work, the aircraft proves ideal. In free flight it is silent, free from vibration, and free from the electrical emissions common to powered aircraft, which can interfere with sensitive instruments.

The aircraft becomes known as the “flying observatory.” Hanna Reitsch tows it during the early test flights.

General Ernst Udet inspects the flying meteorological observatory and immediately sees possible military uses. He believes it could supply encircled units and even imagines it as a modern Trojan horse, landing soldiers unseen behind enemy lines. Udet is not alone. Other forward-thinking Luftwaffe officers share his interest. General Hans Jeschonnek, in particular, presses for the development of a combat version.

From the outset, the project is given a secret classification and handed over to the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug (DFS), which is affiliated with the Rhön Research Institute. Aircraft engineer Hans Jacobsthe chief engineer of the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug assumes responsibility for the programme, assisted by experienced glider pilots on the DFS staff. Jacobs begins the work of transforming the concept into a viable military aircraft.

By the mid-1930’s, advocates of airborne warfare within the Luftwaffe identify a critical limitation in parachute operations. German armed forces are experimenting extensively with parachute troops and developing airborne tactics. No one, however, has yet seen a combat glider, nor has such a weapon been tested under operational conditions.

German planners identify several advantages to glider landings. A glider can carry a small, cohesive unit, delivering a squad of seven to nine soldiers who land together and are ready to fight immediately. Parachute drops, by contrast, scatter troops over wide areas, often 150 to 200 metres apart. Paratroopers must assemble under pressure, losing time and creating confusion. If they are engaged while assembling, casualties can be severe. A glider lands in a confined area and allows its troops to disembark at once, without the need to disentangle themselves from parachute harnesses. Silence is another major advantage. A glider can be released several kilometres from its target and often land without being detected, a level of surprise rarely achieved by parachute operations.

Officers around Oberst Kurt Student, Inspekteur of the Kommando der Flugschulen, therefore seek a different solution. They want a small assault party that arrives together, fully armed, and precisely placed. A troop glider offers that solution. It approaches silently, carries an entire squad, and lands directly on or beside the objective.

In 1936, this idea takes a turn for the good when Adolf Hitler watches gliders practising take-off and landing. During this demonstration, he asks Professor Georgii whether a glider can be built to transport troops. At this time, Georgii serves as head of the Deutschen Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug. The institute operates from Darmstadt and directs the development of gliding in Germany.

Georgii passes the question to Hans Jacobs. At Darmstadt-Griesheim, the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug already possesses the necessary infrastructure. Wind tunnels, sailplane expertise, and experienced engineers are in place. He asks whether such a troop-carrying glider can be designed and built. Jacobs states that the DFS has until then only developed gliders for sporting use. This makes an immediate technical answer difficult.

Jacobs is instructed to design a glider capable of carrying nine fully armed soldiers. It must be able to glide and dive silently, land on short and unimproved fields, and be inexpensive. The target cost is set at 7,500 Reichsmark, calculated to equal the cost of delivering ten men by glider rather than by parachute and matching the manufacturing cost of ten parachutes.

DFS naturally becomes the centre for early military glider development. In practice, it functions as a discreet experimental workshop for the Luftwaffe’s new concept. The project formally begins in October 1936. Jacobs nevertheless recognises a clear operational possibility. He understands that a glider towed to between 1,800 and 2,700 metres can be released. From that height, it can fly many kilometres into enemy territory. He notes that such an aircraft would remain unseen, even in early daylight.

The design work is led by Hans Jacobs himself. He is supported by Heinrich Voepel and Adolf Wanner on aerodynamics, Ludwig Pieler on structural analysis, and Herbert Lück as part of the Darmstadt engineering team.

By early 1937, Jacobs and his team complete a full-scale mock-up. This mock-up is significant. The glider is not an adaptation of a sports glider. It is a purpose-built military transport, designed around the size of a fully equipped infantry party and the need to land in confined, uneven terrain. In their assessment, the design can carry nine troops. The load includes personal weapons and operational equipment. The design demonstrates sufficient internal space and structural strength.

The prototype impresses officials of the Reich Air Ministry. Following inspection, the ministry places an official order. Three experimental aircraft are commissioned. These prototypes receive the designation DFS 230.

During 1937, DFS constructs three flying prototypes under the designation DFS LS. These aircraft, completed as LSS V1 to V3, mark the transition from concept to reality. Flight testing begins the same year.

Hanna Reitsch conducts the first demonstration flight in Munich before a group of senior observers. Among them are the First World War ace von Greim, Albert Kesselring, and Erhard Milch. The flight of the DFS LSS is judged an outstanding success. Contracts are soon negotiated with the Gothaer Waggonfabrik, a railway wagon manufacturer based in Gotha. Despite the enthusiasm of several senior figures, the project does not win universal backing. Some members of the high command worry that the programme lacks direction and imagination.

Oberstleutnant Hans Jeschonnek, then Chief of Operations of the Luftwaffe, summons Oberst Kurt Student to his office. The two men are long-standing friends and colleagues. Jeschonnek explains the glider project and admits bluntly that no one really supports it. He tells Student that the best solution would be for him to take it under his personal supervision, warning that otherwise it will stagnate.

This is Student’s first clear awareness that a transport glider programme exists. He is immediately intrigued and agrees to take responsibility. He flies the glider repeatedly to evaluate its performance. Student judges the design to be excellent. He finds the ratio of empty weight to payload favourable and praises its flying characteristics. From the outset, Student intends to use the glider both as a transport aircraft and as an offensive weapon. Its silence, he believes, makes it ideal for surprise attacks. With Student’s backing, the aircraft enters production. He personally names it the DFS 230 and describes it as an attack glider.

Debate nevertheless continues. Advocates of parachute troops oppose the glider, seeing it as unwelcome competition. Sharp differences of opinion persist within the military.

On May 10th, 1937, the Luftwaffe takes a decisive step. It authorises construction of a first production series. Even at this stage, emphasis lies less on pure flight performance and more on tactical usefulness. Engineers and soldiers test landing accuracy, approach profiles, rollout distance, and the speed with which troops can disembark and fight.

A second demonstration is organised for the Army General Staff at Stendal on November 16th, 1937. Ten Junkers 52 aircraft carry paratroopers, while ten gliders transport glider troops, each towed by an additional Junker 52. The force flies to the airfield at Stendal. The gliders are released and dive steeply to the ground, landing close together in formation. The glider troops disembark as intact units, ready for combat. The paratroopers encounter a strong breeze and are scattered widely on landing. In some cases, they come down far from their ammunition containers, which descend separately by parachute.

The trial evaluates operational factors rather than engineering theory. It measures release distance, descent control, landing precision, and assault readiness. The exercise proves that a glider can place a squad on target faster and more coherently than parachute delivery. The demonstration does not undermine the value of paratroopers, but it clearly shows that a troop-carrying glider can be a highly effective weapon. At this point, the assault glider becomes a weapon system rather than an experimental aircraft.

With the concept validated, the Luftwaffe builds an institutional framework to support it. In 1937, a preparatory glider training course is established at Griesheim. 60 pilots attend under the leadership of Fritz Stamer. On April 1st, 1938, the Luftwaffe forms its first dedicated command for troop and cargo glider operations at Fürstenwalde. This development embeds the DFS 230 within a formal training and operational structure before the war begins.

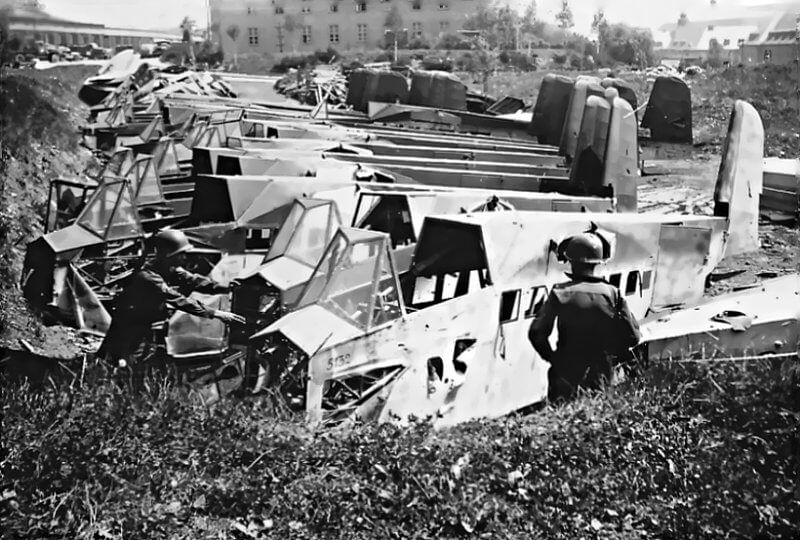

A major obstacle soon emerges. DFS excels at design and prototyping but lacks the capacity for mass production. Large-scale production is initiated under the supervision of the Gotha works, with many firms involved in manufacturing. Early manufacturing begins in July 1939 at Robert Hartwig in Sonneberg, a factory better known for toy production. By June 30th, 1940, 109 gliders are delivered. However, the Luftwaffe identifies a deeper issue. The original DFS design is too complex for economical large-scale manufacture and field maintenance.

To resolve this, responsibility shifts in November 1938 to Gothaer Waggonfabrik. Gotha receives orders to simplify the structure without compromising performance. By the end of March 1939, Gotha completes a revised prototype, designated V5. Testing at Rechlin confirms the changes. This simplified configuration becomes the standard DFS 230 A-1 production model. The process follows a familiar German pattern. A research institute develops the concept. An industrial firm refines it for serial production.

Throughout development, one tactical requirement dominates all design decisions. The glider must land extremely close to the objective, within a very small area, and under full control. This requirement drives several engineering solutions. Jacobs and Wanner conduct formal research into dive-control brakes, producing controllable drag for steep descents. Their work supports approaches that are both sharp and precise. Later variants add braking parachutes and, eventually, nose-mounted braking rockets to further reduce landing distance.

Weight reduction and field practicality remain constant priorities. The DFS 230 uses mixed construction typical of German gliders. Wood and fabric components are combined with a strong fuselage structure. The interior is narrow and uncomfortable by design. Space is sacrificed for weight savings and reduced frontal area. Every aspect of the aircraft reflects its single purpose. It exists to deliver a small assault force exactly where it is needed, under conditions no powered aircraft can tolerate.

The Luftwaffe establishes a dedicated glider training school at Braunschweig-Waggum. Pilots complete a six-week course focused on operational techniques. Training emphasises blind flying, precision navigation, and exact spot landings. Pilots repeatedly practise landing within extremely confined target zones. Exercises include steep descents and short flare-outs to a fixed touchdown point. The objective is to land directly on or immediately beside the target. Training scenarios include simulated landings on fortress roofs and restricted terrain.

Operational doctrine assigns only one pilot to each DFS 230. The standard glider includes a single pilot seat. No reserve pilot is carried during combat missions. To support instruction, dual-control trainer variants are introduced. The DFS 230 A-2 and later B-2 allow an instructor to assume control if required. These versions are used exclusively for training and conversion.

In the months before combat deployment, the DFS 230 undergoes extensive field exercises. Fully loaded gliders operate with various tow aircraft. The Luftwaffe tests multiple towing configurations and release techniques. Crews refine the timing of glider release to achieve precise unpowered approaches. By spring 1940, Allied intelligence identifies the DFS 230 in quantity production. Reports correctly note its capacity of one pilot and nine soldiers. They also identify its intended role in surprise assault operations. The testing phase is complete, and the DFS 230 stands ready for operational use.

Production expands rapidly in the years before the outbreak of war. Manufacture proceeds in secrecy between 1937 and 1939. Early construction takes place at DFS facilities in Darmstadt. Larger-scale production soon transfers to Braunschweig to increase output. Civilian firms are subcontracted to meet rising demand. A toy factory in Thuringia produces early batches. Later production involves Gothaer Waggonfabrik, Bücker, and Erla.

Operational units receive their first DFS 230 gliders in early 1940. These deliveries coincide with preparations for the Western Campaign. By spring 1942, the Luftwaffe fields approximately 700 aircraft. Total production exceeds 1,477 gliders before termination in 1943.

| Multimedia |

| Design Characteristics and Performance |

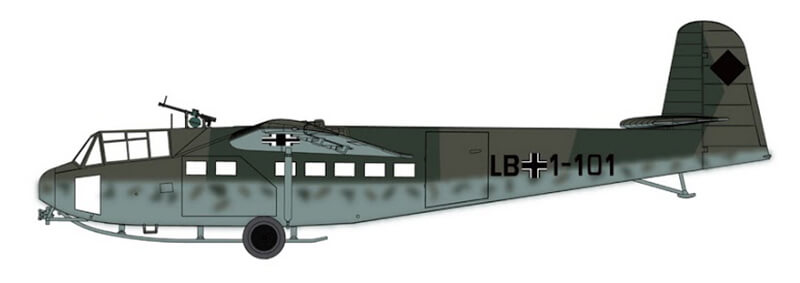

The DFS 230 is designed as a lightweight, high-wing monoplane assault glider with a strut-braced wing. It is intended for one-way combat missions. Recovery after landing is not expected. Construction is therefore kept deliberately light and simple. The design prioritises lift, controllability, and ease of production over long-term durability.

The fuselage consists of a tubular steel frame covered with fabric. This structure provides adequate strength while keeping overall weight low. The troop compartment forms a narrow but rigid cabin. The wings are constructed from wood around a single main spar. They are fabric-covered, with plywood reinforcement along the leading edges. The wing design uses a high aspect ratio to improve glide efficiency. This configuration gives the DFS 230 excellent gliding performance. When fully loaded, the glide ratio is approximately 8 to 1. When empty, it reaches between 15 to 1 and 18 to 1. This performance allows the towing aircraft to release the glider several kilometres from the target. The silent approach preserves surprise, which is critical for assault operations.

In size, the DFS 230 is compact compared to later Allied gliders. The production model has a wingspan just under 22 metres and a length of approximately 11.3 metres. Wing area measures about 41 square metres. Empty weight is approximately 860 kilograms, reflecting the fabric-and-tube construction. Maximum take-off weight is around 2,100 kilograms. This allows a useful load of roughly 1,200 kilograms. In operational use, the glider carries one pilot and 9 fully equipped infantrymen. In some cases, 8 troops are carried with additional equipment.

The interior is extremely confined. Troops sit on a narrow padded bench running along the fuselage. Seating alternates between forward-facing and rear-facing positions to maximise space. The pilot sits alone in the nose section. He operates with only basic flight instruments. These include an airspeed indicator, altimeter, rate-of-climb indicator, turn-and-bank indicator, and compass. Rapid exit after landing is essential. The glider therefore incorporates large openings on both sides of the troop compartment. Troops can exit simultaneously from both sides. The pilot exits through a separate side-hinged canopy.

Despite its simple appearance, the DFS 230 incorporates features specifically designed for assault landings. It has no conventional landing wheels. Take-off is conducted using a jettisonable two-wheel dolly. This dolly is released immediately after the glider becomes airborne. Landing is performed on a strong central skid mounted beneath the fuselage. The skid is spring-loaded to absorb impact forces. It allows the glider to slide to a halt on grass, soil, or rough ground. Later models introduce braking improvements to shorten landing distance. Typical landing speed ranges between 55 and 65 kilometres per hour. This low speed allows touchdown in confined areas or even on man-made structures.

Maximum towing speed ranges between 180 and 209 kilometres per hour. Structural limits dictate this range. After release, the optimal glide speed is approximately 115 kilometres per hour. Stall speed is around 56 kilometres per hour. These characteristics give pilots a wide margin for manoeuvre during the final approach.

Armament is minimal and intended only for immediate self-defence. Early DFS 230 variants carry no weapons. Combat experience leads to the installation of a 7.92 millimetre machine gun on many aircraft. This is typically an MG 34 or MG 15. The weapon is mounted on a swivel at the starboard side of the cockpit or roof. A troop member operates it during the final approach. Fire is directed forward through a narrow opening. Accuracy is limited. Its primary function is suppressive fire during landing. Some later aircraft are fitted with twin forward-firing MG 34 machine guns mounted on the fuselage sides. These fixed guns prove unpopular due to recoil and poor accuracy.

Overall, the DFS 230 sacrifices protection and heavy armament for simplicity and performance. Low weight, high lift, and precise controllability define the design. These qualities make it an effective assault glider for surprise landings under combat conditions.

| Multimedia |

| Variants and Modifications |

During its service life, the DFS 230 undergoes a series of modifications and experimental developments. Each variant seeks to improve landing precision, pilot training, or carrying capacity. These changes reflect operational experience and evolving tactical requirements.

The DFS 230 A-1 enters service as the initial production model. It is a single-pilot assault glider with no onboard armament or special braking equipment. This version establishes the basic dimensions, structure, and performance characteristics used by all later variants. It represents the simplest and lightest operational form of the design.

To support pilot training, the DFS 230 A-2 is developed as a dual-control version of the A-1. An additional set of flight controls is installed. Seating is arranged in tandem so an instructor can supervise a trainee pilot. Apart from the dual controls, performance and handling remain unchanged. The A-2 serves exclusively in training units.

Combat experience leads to the introduction of the DFS 230 B-1. This version incorporates a braking parachute housed in the rear fuselage. The parachute deploys on landing and creates aerodynamic drag. This significantly shortens the landing run. Pilots can now fly steeper approaches and stop within confined spaces. Landing distances can be reduced to approximately twenty to thirty metres. The B-1 also introduces provisions for defensive armament. A rear-facing seven point nine two millimetre MG thirty-four machine gun is mounted to provide limited protection during descent and immediately after landing. From nineteen forty-one onward, most combat operations employ B-series gliders equipped with parachute brakes.

The DFS 230 B-2 combines the features of the B-1 with dual flight controls. Like the A-2, it serves as a training aircraft. It allows instructors to familiarise pilots with braking parachute procedures and armed configurations. The B-2 is not intended for front-line combat use.

Further refinement produces the DFS 230 C-1. This late-production assault variant retains the tail-mounted braking parachute. It also introduces nose-mounted braking rockets. These small reverse-firing rockets activate just above the ground. They sharply reduce forward speed before touchdown. With both parachute and rockets, the C-1 can descend at extremely steep angles. Approaches of up to eighty degrees are possible. The glider can come to a halt within twenty to thirty metres. This capability supports missions requiring exceptional landing precision, including mountain and rooftop landings. The C-1 retains the defensive armament of the B-1. Many special operations during nineteen forty-three and nineteen forty-four use this variant.

The DFS 230 D-1 appears as an experimental refinement of the rocket-brake system. Built as prototype V six, it features an improved nose rocket design. Engineers aim to increase reliability and braking effectiveness. Only one prototype is constructed. It does not enter series production. Technical lessons from the D-1 likely influence the final C-1 configuration.

An attempt to increase troop capacity results in the DFS 230 F-1. This prototype, designated V seven, features a lengthened fuselage and enlarged wing. The wingspan increases to approximately twenty-seven point six metres. The design is intended to carry fifteen troops instead of nine. Testing takes place around nineteen forty-two. By this time, larger transport gliders are already available. These newer designs offer greater capacity with better practicality. As a result, the F-1 remains a single prototype and is not adopted.

Engineers also explore more unconventional configurations. One project joins two DFS 230 fuselages side by side beneath a new central wing section. This twin-fuselage glider, sometimes referred to as DFS 203, has a greatly increased wingspan of approximately twenty-seven point six metres. It is intended to carry heavier loads or multiple squads. Wind tunnel testing reveals no significant advantage over the standard design. The project is abandoned before operational use.

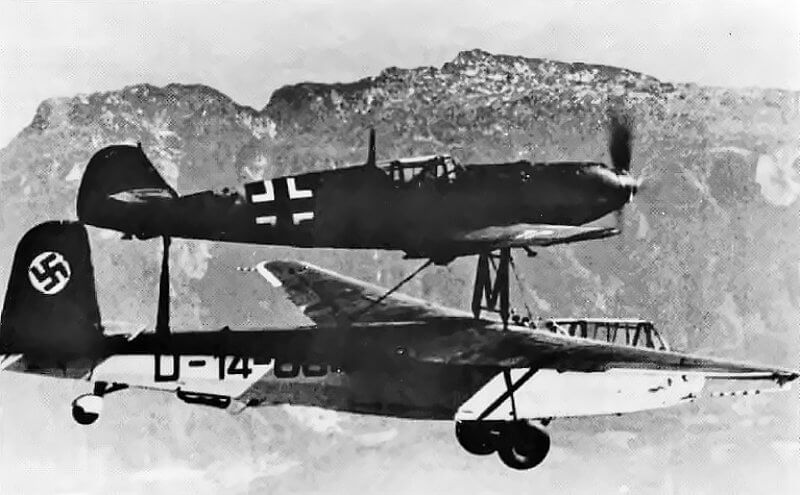

An even more radical experiment produces the Focke-Achgelis Fa 225. In this configuration, the wings of a DFS 230 are replaced with a three-bladed rotor derived from the Fa two hundred and twenty-three helicopter. The rotor spins freely during towing. This enables extremely steep approaches and very short landing runs. Forward speed is greatly reduced. Tests show the aircraft can fly successfully. However, the low towing speed and slow approach make it highly vulnerable in combat. Only one example is built. The concept is abandoned.

German engineers propose several additional ideas using the DFS 230 platform. These include rocket-assisted take-off, water-landing variants with floats, combined aircraft towing arrangements, and even experimental powered assault versions.

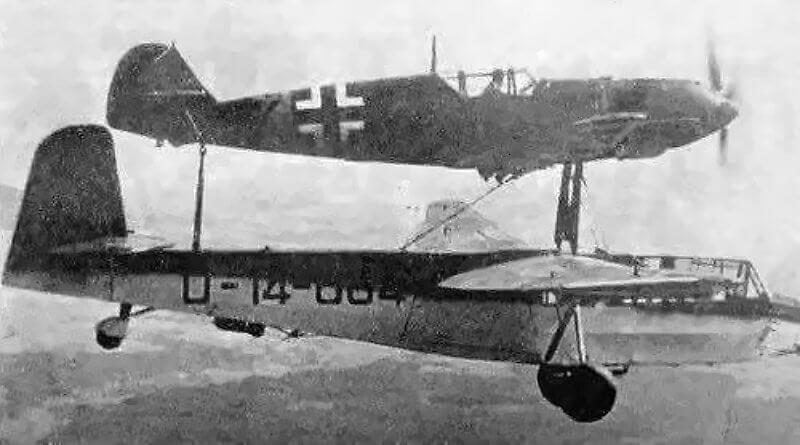

The mistel was a fusion of the DFS 230 with a conventional aircraft. The combination of a DFS 230 glider and an Fw 56 Stösser was one of the first and is extensively tested in October 1942. However, because the Fw 56’s engine power is not sufficient to take off with the composite from the ground, it is lifted into the air while being towed by a Heinkel He 111. The Messerschmitt Bf 109 E with DFS 230 attached underneath it was another one. Another one was the Focke-Achgelis Fa 225 is an experimental hybrid design, with only a single example ever built. It combines the rotor system of the Fa 223 helicopter with the fuselage of a DFS 230B assault glider, intended for Fallschirmjäger insertions into areas where there is insufficient clear ground for a conventional glider landing. A three-bladed autogyro rotor is fitted to the fuselage of a DFS 230. This is done to test the feasibility of a vertical landing system. In practice, the low towing speed makes the combination vulnerable. The system also requires release directly above the target area, which adds further risk.

None progress beyond testing or design studies. In practice, the A, B, and C series, together with their trainer variants, account for nearly all DFS 230’s used operationally. Each modification reflects battlefield experience and the continuing need for greater landing precision under combat conditions.

| Multimedia |

| Engineering and Operational Techniques |

Operating the DFS 230 demands precise coordination and specialised techniques in launch, towing, and landing. The glider has no engine, so every phase depends on external control and timing. Launch and tow procedures are therefore critical to mission success.

Standard practice uses a long towing cable measuring approximately forty to one hundred metres. The primary towing aircraft is the Junkers Ju 52 three-engine transport. In combat operations, the tug usually flies without cargo to maximise available power. One Junker 52 normally tows a single DFS 230. Three Junker 52 aircraft, each with a glider, can take off in V formation to launch a nine-glider assault force simultaneously. This method allows concentrated airborne insertion.

Other aircraft types are also used as tugs when required. Twin-engine bombers such as the Heinkel 111 serve in this role. Dive bombers and fighters are occasionally used under special conditions. During mountain operations in Italy, Junker 87 Stuka dive bombers tow DFS 230 gliders through narrow valleys. Light reconnaissance aircraft and even single-seat fighters tow gliders during training or emergencies. A telephone wire runs along the tow cable. This enables direct communication between tug and glider pilots. It proves especially valuable during blind flying or cloud penetration.

Take-off uses a detachable wheeled dolly beneath the glider. As the tug accelerates, the DFS 230 lifts clear of the ground. The dolly then drops away automatically. The glider continues the tow supported only by its central skid. Typical towing speed ranges between one hundred and fifty and one hundred and ninety kilometres per hour.

Junker 52’s carry a row of eight small lights beneath the tailplane. These are mounted in a V-shaped metal hood facing rearwards. The lights are invisible from the ground but clearly visible to the glider pilot. By keeping the lights in view, the pilot maintains correct position relative to the tow aircraft. If the lights disappear, the glider is either too high or too low.

Thanks to its efficient glide performance, the DFS 230 can be released several kilometres from the objective. Crews aim to release at an altitude not exceeding one thousand five hundred metres. Early release reduces exposure and prevents engine noise from warning the enemy. The tow cable is released either by an explosive bolt or a manual control. From that point, the glider approaches the target in complete silence.

Landing accuracy represents the greatest technical challenge. The DFS 230 is fitted with hinged flaps and air brakes to control descent angle. For confined objectives, these alone are often insufficient. From later A-series models onward, a braking parachute is introduced. This small parachute deploys from the tail during the landing approach. It allows the glider to descend steeply without excessive speed. With the parachute deployed, descent angles of up to eighty degrees become possible. The glider flares just above ground level, with the parachute assisting rapid deceleration after touchdown.

For extreme landing conditions, the C-series introduces nose-mounted braking rockets. These reverse-firing rockets ignite a fraction of a second before touchdown. They dramatically reduce forward speed. Combined use of parachute and rockets enables landings within approximately twenty metres. These methods are hazardous but essential for missions requiring exceptional precision. They prove decisive during operations such as the Gran Sasso raid. They are also planned for the cancelled invasion of Malta, where landing zones are severely restricted.

Once on the ground, stopping distance remains critical. The central skid absorbs impact and allows the glider to slide to a halt. Crews sometimes modify the skid in the field. Barbed wire or improvised hooks are attached to increase ground friction. These measures further shorten the landing run. Sudden deceleration often throws occupants forward. Troops wear padded harnesses, and internal padding reduces injury. Even so, hard landings frequently cause bruises or fractures. The glider’s structure is robust enough to protect occupants in most crash landings. Many gliders strike obstacles or ground loop yet still deliver troops or supplies successfully.

After landing, operational doctrine treats the DFS 230 as expendable. Troops exit rapidly through the side doors and secure the objective. The pilot, usually a Luftwaffe non-commissioned officer, arms himself and joins the ground action. There is normally no plan to recover the glider. To deny intelligence to the enemy, crews often destroy the aircraft after unloading. This is done using demolition charges or by burning the fabric covering.

In some supply missions, particularly on the Eastern Front, recovery is attempted. If a suitable landing area exists, an empty glider may be towed out by a light aircraft or hauled by ground vehicles. Such recoveries are uncommon. The primary objective remains delivery, not retrieval. By design, the DFS 230 accepts one-way use in exchange for the ability to land troops in locations otherwise unreachable.

| Multimedia |

| Operational Use |

The DFS 230 sees operational service across every major theatre in which German airborne forces operate. Its employment ranges from precision assault landings to hazardous supply missions. Throughout the war, the glider proves adaptable to radically different combat environments.

The combat debut of the DFS 230 occurs on the Western Front during the opening hours of the German campaign in the west. In the early morning of ten May nineteen forty, assault gliders land directly on the roof of Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium. The fortress guards key bridges over the Albert Canal and is considered impregnable. A special detachment of the 7. Flieger-Division, led by Rudolf Witzig, employs nine DFS 230 gliders. They carry seventy-eight assault troops equipped with explosives and silenced weapons. The gliders are released at low altitude after being towed from many kilometres away. They descend silently and land before the defenders can react. Assault teams immediately neutralise gun turrets and strongpoints using shaped charges. Other gliders land near the canal bridges and seize them intact. After a day of internal fighting, the Belgian garrison surrenders.

The Eben-Emael assault demonstrates the full potential of glider warfare. The defenders expect parachute landings and prepare accordingly. The silent rooftop landings bypass all external defences. German losses remain minimal. The strategic effect far exceeds the size of the force involved. Military observers worldwide recognise glider assault as a new form of warfare. Other major powers rapidly begin their own glider programmes. Within Germany, the success strengthens confidence in airborne forces.

The DFS 230 next sees large-scale use during the invasion of Crete in May 1941. During Operation Merkur, approximately 90 gliders deploy alongside mass parachute drops. Glider-borne troops land near Maleme airfield and positions around Hania. Many land directly on or beside defended objectives. Allied forces are alert and prepared, reducing surprise. However, the gliders still deliver troops with precision. On landing, the skids raise clouds of dust on the dry terrain. This dust briefly conceals the assault teams as they disembark. German forces secure footholds near Maleme. This enables air transport landings within twenty-four hours. After ten days of heavy fighting, Crete falls. German casualties are severe. The losses prompt Adolf Hitler to prohibit further large-scale airborne invasions. Crete becomes the final mass assault operation for the DFS 230.

After Crete, the glider’s role shifts toward transport and supply. This is especially true in North Africa. Long distances and limited infrastructure complicate logistics. The DFS 230 delivers ammunition, fuel, and medical supplies to forward Afrika Korps units. Gliders land at night near isolated positions without prepared airstrips. In late nineteen forty-one, gliders resupply German detachments cut off in the Libyan desert. The small ground footprint of a glider makes concealment easier than a transport aircraft. Many gliders are abandoned after unloading.

German planners also prepare the DFS 230 for Operation Herkules, the planned invasion of Malta in nineteen forty-two. Several hundred gliders are allocated for the assault. Modifications include braking parachutes to handle rocky landing zones. Glider strips are prepared in Sicily. However, changing strategic priorities delay the operation. By November nineteen forty-two, the plan is cancelled. The DFS 230 never conducts another large-scale assault in the Mediterranean. It continues transport duties in Tunisia and between Italy and North Africa until Allied advances cut supply routes.

One of the most famous DFS 230 missions occurs in Italy during September nineteen forty-three. Following Italy’s armistice, Benito Mussolini is imprisoned at the Hotel Campo Imperatore on the Gran Sasso plateau. Adolf Hitler orders a rescue operation. On twelve September, twelve DFS 230 gliders are towed into the Apennine mountains. Each carries a pilot and nine troops. Conditions are extreme. Thin air, strong winds, and a tiny landing area complicate the approach. Guided by a Fieseler Storch, the gliders descend steeply and land on a narrow meadow beside the hotel. Several strike rocks or obstacles. All land without fatal casualties. Assault troops quickly overwhelm the guards. Mussolini is extracted without resistance. The mission succeeds completely. Many gliders use braking rockets to avoid overshooting the plateau. Afterward, the gliders are destroyed on site. The operation becomes legendary. The DFS 230 proves decisive in delivering a strike force to an otherwise inaccessible location.

On the Eastern Front, the DFS 230 assumes a vital supply role. German forces often operate far from supply bases and face encirclement. The Luftwaffe forms dedicated glider supply units. Gliders deliver food, ammunition, medical supplies, and dismantled weapons. During the Demyansk Pocket in winter nineteen forty-one to nineteen forty-two, gliders land on frozen lakes and improvised fields. They supplement Ju fifty-two transport aircraft. Some evacuate wounded on return tows. Similar missions occur at Kholm. These operations demonstrate the value of gliders where runways do not exist.

During the Stalingrad encirclement, glider use is considered but never executed. Proposals call for heavy glider deliveries onto frozen terrain. High winds, enemy fire, and shrinking landing zones prevent implementation. Trainloads of DFS 230s reach forward areas but are never deployed. The episode highlights the desperation of the situation rather than operational success.

Late in the war, gliders again support besieged garrisons. During the siege of Budapest in winter nineteen forty-four to nineteen forty-five, DFS 230s deliver supplies into the city. They land or crash-land in parks and open spaces under fire. Many fail to reach their targets. Some succeed in delivering limited supplies. Similar missions reportedly occur at Breslau and even within Berlin during the final months of the war. Fuel shortages and Allied air dominance make powered transport difficult. Gliders provide a final, silent alternative.

By the end of the war, the DFS 230 is obsolete and highly vulnerable. Despite this, it continues flying until Germany’s collapse. Its operational history demonstrates both innovation and desperation. Throughout the conflict, the DFS 230 remains a unique tool for precision landing and last-resort resupply under extreme conditions.

| Multimedia |

| DFS 230 in Rumanian Use |

The Germans also send 38 DFS 230’s to Rumania for use by the Rumanian Air Force. Military transport glider training begins in Romania during the later stages of the war. Between April 1st, 1943, and August 26th,1943, the first organised instruction for transport glider pilots takes place at the Focșani South airfield. The school operates under the command of Lieutenant aviator Mircea Gabureanu. He receives technical support from German personnel led by Captain aviator Alois Fluke. The instructional staff also includes Unteroffizier Hans Adomait, Fritz Kalmayer, and Paul Müller.

The first training group consists of 18 military glider pilots. They are selected from experienced civilian glider pilots. Most already hold licences for powered aircraft. Two civilian gliding instructors also participate. They are Mihai Golescu and Valentin Popescu. Preliminary instruction is conducted on two-seat training gliders. These include the Go 4 Goevier and the Kranich II. Both types are towed by PWS 26 aircraft. In the final phase, pilots transition to the DFS 230. Training focuses on operational transport techniques and precision landings.

After 4 months of instruction, an examination commission is convened. It is led by General Gheorghe Jienescu, Minister of Air. Commander aviator Mihai Pavlovski also serves on the board. He holds transport glider licence number 1. The commission awards military transport glider licences to 21 pilots. All licensed pilots are assigned to wartime transport missions on the Eastern Front. They operate primarily from Băneasa Airfield to Odessa.

On November 11th, 1943, a dedicated glider transport unit is established. It is designated Escadrila 109 Planoare Transport. Command is given to Lieutenant aviator Mircea Gabureanu. The squadron operates 9 DFS 230 gliders. Towing support is provided by 7 IAR 39 biplanes. The unit is initially based at Băneasa. In December 1943, it relocates to Spătaru near Buzău.

A second training cycle begins in late 1944. Between August 20th, 1944, and November 25th, 1944, new DFS 230 pilots undergo instruction at the Petrești–Dâmbovița airfield near Găești. Lieutenant aviator Mircea Gabureanu again commands the school. Instruction is provided by Nicolae Cătana, Eugen Costin, and Mihai Făgăraș. On November 18th, 1944, 14 pilots receive military transport glider licences.

Romanian transport gliders later deploy to the Western Front. From February 14th, 1945, the Mixed Air Transport Squadron begins redeployment. The unit combines transport aircraft and gliders from Flotila 7 Aerotransport București. It joins the Corpul Aerian Român in operations to the west. The glider element consists of 5 DFS 230 aircraft. Missions include personnel transport and the delivery of ammunition, fuel, and food. Operations support front-line forces in Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

During operations on the Western Front, Romanian DFS 230 gliders complete 579 missions. They accumulate 1,165 flying hours. They transport a total of 463.2 tonnes of material. These sorties represent the final wartime employment of DFS 230 gliders in Romanian service.

| Multimedia |

| Sources |

Thanks for every one of your hard work on this website. My daughter really likes doing internet research and it is easy to understand why. You have been conducting a first-class job.