| Page Created |

| December 21st, 2025 |

| Last Updated |

| January 19th, 2026 |

| Germany |

|

| Related Pages |

| Fort d’Ében-Émael DFS 230, Lastensegelflugzeug |

| Fall Gelb, May 10th, 1940 – May 31st, 1940 |

| Objectives |

- Defeat France and Eliminate Western Opposition

- Avoid a Two-Front War

- Secure Strategic Territory and Forward Bases

| Operational Area |

- The Netherlands

- Belgium

- France

| Allied Forces |

France

- Groupe d’Armées n°1 (GA1) Nord / Belgique

- 1re Armée

- 1re Division d’Infanterie

- 2e Division d’Infanterie Nord-Africaine

- 3e Division d’Infanterie Motorisée

- 4e Division d’Infanterie

- 12e Division d’Infanterie Motorisée

- 15e Division d’Infanterie Motorisée

- 25e Division d’Infanterie Motorisée

- 1re Division Légère Mécanique

- 2e Division Légère Mécanique

- 3e Division Légère Mécanique

- 7e Armée

- 4e Division d’Infanterie

- 21e Division d’Infanterie

- 60e Division d’Infanterie

- 68e Division d’Infanterie

- 1re Division Légère de Cavalerie

- 2e Division Légère de Cavalerie

- 1re Armée

- Groupe d’Armées n°2 (GA2) Ligne Maginot

- 2e Armée (secteur Sedan – Montmédy)

- 3e Division d’Infanterie Nord-Africaine

- 41e Division d’Infanterie

- 55e Division d’Infanterie

- 71e Division d’Infanterie

- 1re Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 3e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 3e Armée (secteur Metz)

- 6e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 7e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 8e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 42e Division d’Infanterie

- 51e Division d’Infanterie

- 4e Armée (secteur Sarre)

- 9e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 10e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 21e Division d’Infanterie

- 43e Division d’Infanterie

- 52e Division d’Infanterie

- 5e Armée (secteur Alsace du Nord – Haguenau)

- 11e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 12e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 24e Division d’Infanterie

- 28e Division d’Infanterie

- 62e Division d’Infanterie

- 8e Armée (secteur Alsace du Sud – Rhin)

- 13e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 14e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse

- 54e Division d’Infanterie

- 57e Division d’Infanterie

- 63e Division d’Infanterie

- 2e Armée (secteur Sedan – Montmédy)

- Marine nationale

- Forces Maritimes du Nord

- Forces Maritimes de l’Atlantique

- Bataillons de fusiliers marins

- Compagnies de défense des ports

- Artillerie de marine (côtière)

- Armée de l’Air

- Groupements de Chasse

- GC I/1

- GC II/1

- GC I/2

- GC II/2

- GC I/3

- GC II/3

- GC I/4

- GC II/4

- Groupements de Bombardement

- GB I/12

- GB II/12

- GB I/31

- GB II/31

- GB I/34

- GB II/34

- Groupements de Reconnaissance

- GR I/14

- GR II/14

- GR I/33

- GR II/33

- Groupements de Chasse

Great Britain

- British Expeditionary Force (BEF)

- I Corps

- 1st Infantry Division

- 2nd Infantry Division

- II Corps

- 3rd Infantry Division

- 4th Infantry Division

- III Corps

- 42nd (East Lancashire) Infantry Division

- 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division

- 48th (South Midland) Infantry Division

- Armoured & Support Formations

- 1st Armoured Division (partially committed)

- 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (attached to French command)

- Royal Navy

- Admiralty

- Dover Command

- Portsmouth Command

- Home Fleet

- Royal Marines

- Marine infantry battalions

- Depot and harbour defence units

- Royal Air Force

- Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF)

- No. 71 Wing

- No. 72 Wing

- RAF Air Component (British Expeditionary Force)

- No. 60 Wing

- No. 61 Wing

Belgium

- Armée de campagne

- 1re Division d’Infanterie

- 2e Division d’Infanterie

- 3e Division d’Infanterie

- 4e Division d’Infanterie

- 5e Division d’Infanterie

- 6e Division d’Infanterie

- 7e Division d’Infanterie

- 8e Division d’Infanterie

- 9e Division d’Infanterie

- 10e Division d’Infanterie

- 11e Division d’Infanterie

- 12e Division d’Infanterie

- 13e Division d’Infanterie

- 14e Division d’Infanterie

- 15e Division d’Infanterie

- 16e Division d’Infanterie

- 17e Division d’Infanterie

- 18e Division d’Infanterie

- Chasseurs Ardennais

- 1re Division de Chasseurs Ardennais

- 2e Division de Chasseurs Ardennais

- Force Navale Belge

- Very limited

- Aéronautique Militaire

- Groupes de Chasse

- 1er Groupe de Chasse

- 2e Groupe de Chasse

- Groupes de Bombardement

- 3e Groupe

- 5e Groupe

- Escadrilles de Reconnaissance

- Escadrilles d’observation indépendantes

The Netherlands

- Koninklijke Landmacht

- I Legerkorps

- 1e Divisie

- 2e Divisie

- II Legerkorps

- 3e Divisie

- 4e Divisie

- III Legerkorps

- Depending on Region

- Mobiele reserve

- Lichte Divisie

- Vestingtroepen

- Troepen Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie

- Vesting Holland

- Afsluitdijk-detachementen

- Koninklijke Marine

- Zuiderzeevloot

- Kust- en Estuariumverbanden

- Onderzeedienst

- Marine Luchtvaartdienst

- Haven- en Kustverdediging

- Korps Mariniers

- 1ste Mariniers Bataljon

- Depot- en opleidingscompagnieën

| Axis Forces |

Heeresgruppe A

- 4. Armee

- 5. Infanterie-Division

- 6. Infanterie-Division

- 32. Infanterie-Division

- 34. Infanterie-Division

- 52. Infanterie-Division

- 56. Infanterie-Division

- XV. Armeekorps (mot.)

- 5. Panzer-Division

- 7. Panzer-Division

- 12. Armee

- 26. Infanterie-Division

- 27. Infanterie-Division

- 35. Infanterie-Division

- 45. Infanterie-Division

- 55. Infanterie-Division

- 72. Infanterie-Division

- 78. Infanterie-Division

- Panzergruppe Kleist

- XIX. Armeekorps (mot.)

- 1. Panzer Division

- 2. Panzer Division

- 10 Panzer Division

- Infanterie-Regiment „Großdeutschland“ (mot.)

- XLI. Armeekorps (mot.)

- 6. Panzer-Division

- 8. Panzer-Division

- 16. Armee

- 14. Infanterie-Division

- 16. Infanterie-Division

- 30. Infanterie-Division

- 46. Infanterie-Division

- 62. Infanterie-Division

- XIX. Armeekorps (mot.)

Heeresgruppe B

- 6. Armee

- 17. Infanterie-Division

- 18. Infanterie-Division

- 30 Infanterie-Division

- 32 Infanterie-Division

- 44 Infanterie-Division

- 56 Infanterie-Division

- XVI. Armeekorps (mot.)

- 3. Panzer-Division

- 4.Panzer Division

- 18. Armee

- 9. Infanterie-Division

- 22. Infanterie-Division (Luftlande)

- 30. Infanterie-Division

- 50. Infanterie-Division

- 225. Infanterie-Division

- 9. Panzer Division

Heeresgruppe C

- 1. Armee

- 12. Infanterie-Division

- 21. Infanterie-Division

- 25. Infanterie-Division

- 86. Infanterie-Division

- 7. Armee

- 60. Infanterie-Division

- 79. Infanterie-Division

- 83. Infanterie-Division

Luftflotte 2

- II. Fliegerkorps

- 2. Flieger-Division

- 3. Flieger-Division

- V. Fliegerkorps

- 9. Flieger-Division

- VIII. Fliegerkorps (Stuka-Schwerpunkt)

- 8. Flieger-Division

- Luftlandeverbände (direkt OKL / Luftflotte 2 zugewiesen)

- 7. Flieger-Division (Fallschirmjäger)

- 22. Infanterie-Division (Luftlande)

Luftflotte 3

- I. Fliegerkorps

- 1. Flieger-Division

- 7. Flieger-Division

- IV. Fliegerkorps

- 4. Flieger-Division

- X. Fliegerkorps

- 10. Flieger-Division

Abwehr

- Lehr-Regiment “Brandenburg”

- Infanterie-Batallion zBV 100

| Planning an Offensive in the West |

In the autumn of 1939, as the Polish campaign ends, Adolf Hitler turns his attention westward. He demands a rapid offensive against France and the Low Countries. The operation receives the code name Fall Gelb. Germany’s primary strategic aim in Fall Gelb is the rapid defeat of France. Adolf Hitler views a swift western victory as essential. France represents the main continental threat. Its removal promises strategic freedom of action. German leaders believe a rapid collapse will shock Europe. They also expect it to undermine Allied morale. A defeated France may leave Great Britain isolated. German planners hope Britain will then seek negotiation.

Securing the Western Front becomes the immediate objective. Hitler is determined to avoid a repeat of the First World War. He refuses to fight simultaneously in east and west. A neutralised France removes the western danger. Germany can then redirect forces elsewhere. Eastern ambitions remain central to long-term strategy. Directive Number Six reflects this logic. Preparations in the west serve as a preliminary step. Victory in Western Europe prevents a prolonged two-front conflict. Strategic focus can then shift without constraint.

Fall Gelb also targets the occupation of key territory. The Low Countries and northern France hold great strategic value. Their seizure pushes Allied air forces away from German industry. The Ruhr gains increased protection from bombing. Control of the Channel coast offers new advantages. Airfields and ports become available for future operations. These bases strengthen pressure against Britain. Hitler emphasises territorial gain in his directive. Occupied regions serve as both buffer and springboard. Strategic depth and operational reach expand together.

Planning begins before fighting in Poland fully concludes. The German Army High Command starts early work under Generaloberst Walter von Brauchitsch and General Franz Halder. At the same time, the Armed Forces High Command operates under General Wilhelm Keitel. Between late 1939 and May 1940, Germany undertakes intensive preparation. Training expands, forces redeploy, and doctrine evolves. The result is a bold operational concept for the western campaign.

| Early Plans and Hitler’s Directive No. 6 (October 1939) |

On October 9th, 1939, Hitler issues Führer Directive Number Six. He orders preparations for a western offensive to begin immediately. Many senior officers still expect a long war of attrition. Early planning reflects this cautious outlook. The Army High Command produces Aufmarschanweisung Nr. 1 for Fall Gelb. This draft appears in early October 1939.

The original plan for Fall Gelb reflects a cautious approach. It is devised by General Franz Halder. The concept closely resembles methods from the First World War. It calls for a broad advance through central Belgium. German forces aim to reach the Somme line in northern France.

Most units push west after crossing Belgium. The advance remains limited in depth. The objective is to drive Allied forces away from the German frontier. Securing territory in northern France is the priority. The plan does not seek a decisive blow. It is not intended to destroy the French Army outright.

Halder’s design assumes limited endurance. German strength is expected to peak after reaching the Somme. Consolidation follows during 1940. A final offensive against France is postponed. Full victory is anticipated only in 1941 or 1942.

Dissent emerges within Army Group A. Generalleutnant Erich von Manstein, its chief of staff, challenges the concept. Repeated war game criticism exposes weaknesses in the original concept. The Mechelen incident alarms German leadership.

| Manstein’s Plan |

Meanwhile Generalleutnant von Manstein argues that a Belgian advance creates another static front. He advocates a decisive armoured breakthrough instead. Working with Heinz Guderian, Manstein develops an alternative concept. They concentrate armoured forces in the Ardennes sector. They target the Meuse crossings near Sedan. From there, they plan a rapid drive to the Channel coast. This manoeuvre aims to encircle Allied armies in Belgium. The proposal becomes known as the Sichelschnitt concept. It directly contradicts the Army High Command’s conservative approach. Manstein submits several memoranda between October 1939 and January 1940. Each version becomes more radical. The High Command rejects every submission. Halder arranges Manstein’s transfer to remove him from influence.

Manstein’s proposal overturns earlier assumptions. Army Group A in the south becomes the main striking force. Army Group B’s advance into Belgium loses primacy. It now serves a supporting role. The operational aim expands dramatically. German forces no longer seek territorial gain alone. They aim to encircle and destroy Allied armies.

The advance into the Low Countries becomes a deliberate diversion. It exploits French expectations of a repeat of 1914. Allied forces move north accordingly. The real Schwerpunkt shifts south. Armoured forces break through at Sedan. They drive deep toward the Channel coast. The goal is isolation, not attrition.

During this period, Hitler presses for immediate action. He repeatedly sets provisional attack dates. Weather and incomplete readiness force repeated postponements. Forces redeploying from Poland require refitting and training. Autumn rains further restrict offensive prospects. The invasion date changes many times during late 1939. Each delay frustrates Hitler. These postponements prove operationally valuable. They allow training improvements and equipment upgrades. They also create space for fundamental revision of the plan.

| The Phony War Winter: Refining and Rethinking the Plan |

The winter of 1939 to 1940 passes without fighting on the Western Front. This period becomes known as the Phoney War. Despite the absence of combat, German preparation intensifies. Training continues, units redeploy, and planning accelerates. Franz Halder issues Aufmarschanweisung Number Two and Number Three for Fall Gelb. These revisions introduce minor adjustments. The core concept remains a frontal advance through Belgium.

German commanders conduct staff exercises and map war games throughout the winter. These exercises test timing, movement, and coordination. The results expose serious weaknesses in Halder’s approach. They also strengthen arguments for an alternative strategy.

War games held on February 7th and February 14th, 1940, prove decisive. Panzer commanders demonstrate the speed of concentrated armoured forces. They show that armoured formations can reach the Meuse within five days. Infantry formations require more than nine days even to begin a crossing. This delay risks operational paralysis.

In one simulation, Heinz Guderian outlines a detailed advance. His XIX Panzer Corps crosses the Luxembourg border on the first day. It reaches Neufchâteau on the second day. It passes Bouillon and the Semois River on the third day. It reaches the Meuse on the fourth day. It forces a crossing on the fifth day. The scenario highlights decisive tempo.

These results reach Adolf Hitler during a Berlin briefing. Hitler questions Guderian about the next step. Guderian replies that he would exploit success and drive to the Channel coast. Hitler listens closely. He offers silent approval.

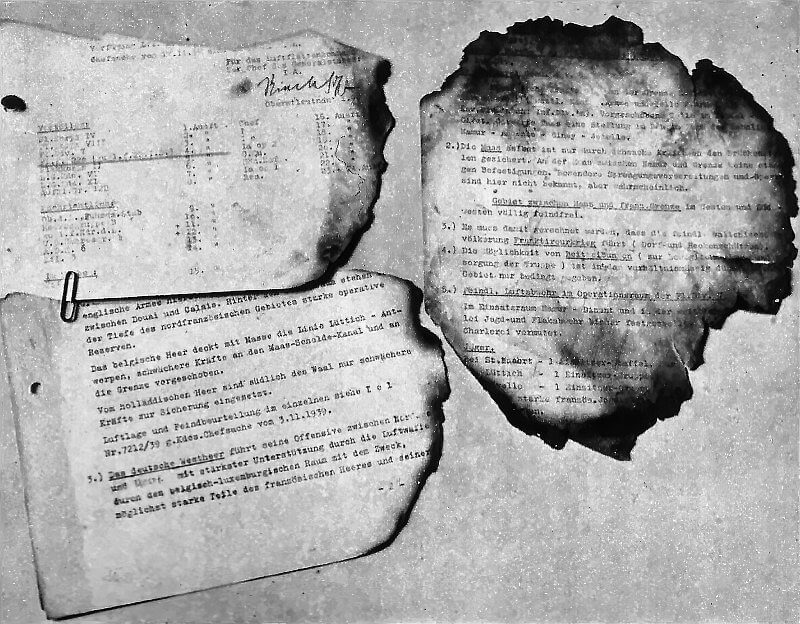

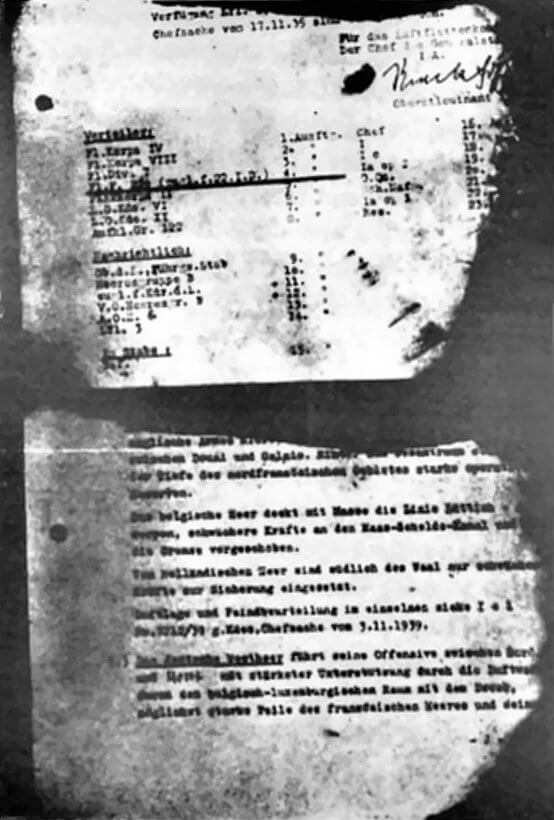

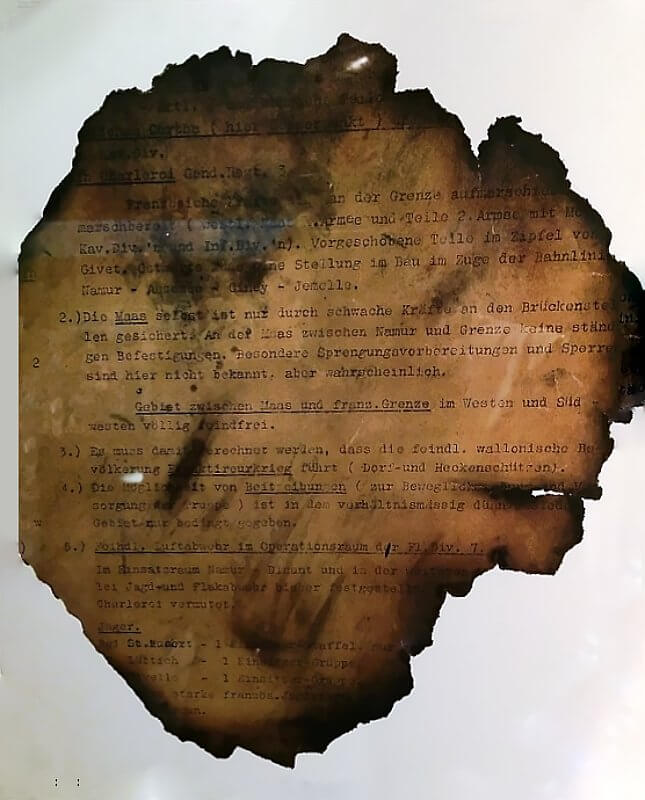

Events outside the planning rooms also influence strategy. On January 10th, 1940, a German aircraft force-lands near Maasmechelen in Belgium. It carries parts of the invasion plan. Belgian authorities seize the documents. German leaders react with alarm.

| The Mechelen incident |

At Fliegerhorst Münster-Loddenheide, near the city of Münster, an almost chance meeting occurs on the evening of 9 January 1940. Major Helmut Reinberger is newly stationed at the airfield. He serves as liaison officer to the 7. Flieger-Division. Reinberger prepares to retire for the night. The following day requires a long train journey to Cologne. A staff conference of IV. Fliegerkorps awaits him. Fellow officers persuade him to join them for drinks in the officers’ mess.

There he meets Erich Hönmanns. Hönmanns is the commandant of the airfield. The two men recognise one another from earlier service. During their conversation, Hönmanns explains his plans for the next day. He must carry out a reconnaissance flight. He also wishes to visit his wife in Münster. He proposes combining both tasks. He offers Reinberger a flight to Cologne.

Reinberger dislikes the prospect of a lengthy rail journey. He accepts the offer, provided the weather remains favourable. They agree to depart at 09.00 hours the next morning. They plan to return from Cologne between 15.00 and 16.00 hours. Reinberger does not inform Hönmanns that he carries secret documents. He also omits that his orders require travel by train.

Major Helmut Reinberger is a veteran of the First World War. He belongs to the early generation of German Fallschirmjäger. He previously commands several parachute training schools. With an invasion in the west approaching, he joins the staff of the 7. Flieger-Division. His role is liaison between the division and supporting formations. He is formally responsible for organising parachutist transport to operational areas.

Major Erich Hönmanns is also a First World War veteran. He serves with distinction as a balloon observer and later as a fighter pilot. After the war he transfers to the reserve. He is recalled to service in 1939. A heart condition bars him from operational flying. He is therefore appointed airfield commander.

Despite this, he secures a temporary flying permit. The condition limits him to non-operational flights. He eagerly exploits every opportunity to fly. He frequently uses the Messerschmitt Bf 108 D-NFAW based at the airfield. It is in this context that he offers Reinberger a lift to Cologne.

On the morning of January 10th, 1940, he flies a Messerschmitt Bf 108 from Münster to Cologne. Dense fog reduces visibility. Hönmanns becomes disoriented. He alters course westward, hoping to locate the Rhine.

He unknowingly crosses the frozen Rhine. He leaves German airspace. He reaches the Maas, which marks the Belgian Dutch border. He circles above Vucht. While descending to about 200 to 300 metres, he accidentally cuts the fuel supply. The engine fails. At around 11.30, he lands in a nearby field. The aircraft is destroyed. Hönmanns survives uninjured.

After landing, the men ask a local farm worker for directions. They learn they are in Belgium. Major Reinberger panics. He returns to the aircraft. He attempts to destroy the documents. He first tries to burn them with a lighter. It fails. He obtains matches from the farm worker.

Belgian military cyclists arrive quickly. They belong to the 13de Infantrie Division. They see smoke. They intervene before destruction is complete. Reinberger attempts to flee. Warning shots force his surrender.

The men are taken to a Belgian border post near Mechelen-aan-de-Maas. Captain Alfons Rodrique conducts questioning. Major Reinberger attempts further destruction. He tries to burn the papers in a stove. He burns himself. Rodrique retrieves the documents. Reinberger becomes hysterical. He attempts to seize Rodrique’s revolver. He is restrained.

Later that day, Belgian military intelligence arrives. The documents are transferred for analysis. That evening, senior officers are informed. The next morning, a full report is delivered.

The documents include orders from Luftflotte 2. They include instructions for the 7. Flieger Division. They reference bridges, obstacles, and targets. The edges are burned. The outline of an attack on Belgium and the Netherlands is clear. No attack date appears.

Belgian leaders compare the material with prior warnings. These include information from Italian sources. On January 11th, 1940, the material is judged credible. King Leopold the Third informs Belgian and Allied leaders. France and Great Britain receive summaries. The Netherlands and Luxembourg are warned through coded messages.

One day later, on January 12th, 1940, French command meets. Intelligence officers express doubt. General Gamelin sees opportunity. Even if false, pressure on Belgium may yield advantage. French forces could deploy forward. Preparations begin. French units move toward the Belgian border. Belgian concern intensifies. New intelligence arrives from Berlin. The source suggests immediate invasion. Belgian leadership debates its validity. General Van Overstraeten revises warnings. An attack is now described as almost certain. That evening, Belgium orders a full recall of leave. Eighty thousand soldiers return to units. Border obstacles facing France are removed. This allows Allied entry if required. These actions occur without royal approval. When no attack follows, political consequences ensue. The Belgian Chief of Staff is reprimanded. He later resigns.

Dutch leaders receive Belgian warnings. Military command remains sceptical. Precautionary measures follow. Leave is cancelled. Bridges are prepared for demolition. Public concern rises. Measures are taken to counter fears of frozen defences.

Belgian neutrality remains official policy. Diplomatic exchanges occur with Great Britain and France. Misunderstandings arise. French leaders believe Belgium may invite Allied forces. This does not occur. Border barriers are restored. Allied forces withdraw.

On the evening of January 10th, 1940, news reaches the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht in Berlin. Both German servicemen are now in Belgian custody. German leaders quickly draw conclusions. Given Major Reinberger’s role, he must have carried sensitive documents. These likely include elements of the invasion plan.

Adolf Hitler reacts with fury on January 11th, 1940. He orders the immediate dismissal of Hellmuth Felmy, commander of Luftflotte Two. He also removes Felmy’s chief of staff, Josef Kammhuber. Despite this reaction, preparations for the offensive continue. No final assessment is yet available.

The Luftwaffe attaché in The Hague, Ralph Wenninger, receives instructions. The military attaché in Brussels, Friedrich-Karl Rabe von Pappenheim, receives the same order. Both men must determine how much the plans are compromised. They are scheduled to meet Reinberger and Hönmanns on January 12th, 1940.

On that same day, General Alfred Jodl briefs Hitler. He outlines what the Belgians may have learned from the papers. He warns of catastrophic consequences if the documents remain intact.

Before the attachés gain access, Belgian authorities act deliberately. They aim to convince Reinberger that the documents are almost completely destroyed. Interrogations are conducted with care. The Belgians appear unable to understand the remaining text. They threaten Reinberger with execution as a spy. They suggest cooperation may save him.

Subsequent meetings are closely monitored. Conversations between the two Germans and the attachés are secretly recorded. The deception appears effective. Reinberger states that the documents are destroyed. He believes the crucial sections no longer exist.

This assessment reaches Berlin through attaché reports. It reassures senior command. Jodl accepts the conclusion. He reports that the documents are considered destroyed.

Weather conditions worsen. Snow hampers movement. On January 15th, 1940, advisers recommend cancellation. On January 16th, 1940, the invasion is postponed by Adolf Hitler.

| Multimedia |

| Revisions Of Fall Gelb |

Halder responds with limited amendments. He issues a revised Fall Gelb order on January 30th, 1940. These changes remain superficial. No strategic transformation follows. Hitler grows dissatisfied. His instincts favour an unexpected blow.

During this period, Manstein is removed from Army Group A. The transfer takes effect on January 27th, 1940. The intention is to silence his criticism. Manstein’s staff continues to act independently. They forward his memorandum through unofficial channels.

On February 2nd, 1940, Hitler reads Manstein’s proposal. The concept matches Hitler’s own thinking. It emphasises an attack through the Ardennes. Hitler summons Manstein for a personal meeting.

On February 17th, 1940, Manstein presents his plan in full. The meeting takes place at Hitler’s headquarters. Manstein proposes that Army Group A deliver the main blow. The attack passes through the Ardennes and across the Meuse. Army Group B advances into the Netherlands and northern Belgium. This northern attack serves as a diversion.

The manoeuvre aims to encircle Allied forces moving eastward. Hitler immediately recognises its potential. The plan promises decisive victory. On the following day, Hitler orders its adoption. Fall Gelb is restructured around the armoured sickle cut. The High Command receives instructions to rewrite all operational orders accordingly.

| The Manstein Plan Emerges (February 1940) |

After Hitler’s intervention, the German plan changes rapidly. Franz Halder experiences what he later calls an astonishing change of opinion. He accepts that the Schwerpunkt must lie at Sedan in the Ardennes. Under Hitler’s authority, the Army High Command issues Aufmarschanweisung Number Four for Fall Gelb on February 24th, 1940. This order incorporates the core of Manstein’s concept.

The revised plan heavily reinforces Army Group A under General von Rundstedt. Army Group B is weakened accordingly. Seven Panzer divisions and three motorised infantry divisions shift southwards. In total, twenty divisions move from the northern wing to the Ardennes concentration. Army Group B retains enough strength to attack the Netherlands and Belgium.

The operational logic is deliberate. Army Group B advances into the Low Countries. This move draws Allied main forces north under the Dyle Plan. Meanwhile, Army Group A masses armour in the Ardennes. The Allies consider this region unsuitable for large formations. Once Allied forces commit in Belgium, Army Group A breaks out. It crosses the Meuse at Sedan. It then drives west to the Channel coast. The manoeuvre aims to encircle Allied armies in northern Belgium.

At the tactical level, German planning defines a set of clear objectives. Each objective exists to enable rapid advance and encirclement. Tactical success serves the wider intent of Fall Gelb.

A primary objective is the rapid seizure of key cities and capitals. Important urban centres are targeted to unbalance enemy command and morale. The capture of Rotterdam aims to break Dutch resistance and force political collapse. The occupation of Brussels and Antwerp seeks to disrupt Allied defensive lines and compel continued withdrawal. The eventual capture of Paris is intended to cripple French resistance symbolically and materially. Control of capitals supports political victory alongside military success.

Another central objective is the seizure of vital river crossings. Bridges and canals must be taken intact before demolition. This requirement applies especially to the Albert Canal and the Meuse. Intact crossings allow uninterrupted momentum. Loss of bridges risks operational paralysis. Speed across waterways is therefore essential.

A related objective is the rapid crossing of the Meuse River. Breaking this line quickly prevents organised defence. Early seizure of bridgeheads denies time for enemy reserves to react. Success here opens the operational depth required for exploitation.

The neutralisation of fortresses and defensive strongpoints forms another objective. Fortified positions that dominate routes or crossings must be eliminated rapidly. Fort Eben-Emael represents the clearest case. Its suppression removes the principal barrier to movement in eastern Belgium. Eliminating such positions prevents delay and preserves tempo.

Air superiority constitutes a further tactical objective. Control of the air denies the enemy observation, movement, and counter-attack capability. Suppressing Allied air forces enables freedom of action on the ground. Close air support assists breakthrough and dislocation of defences. Air dominance ensures uninterrupted advance.

These objectives operate in concert. City seizure undermines cohesion. Bridge capture preserves speed. Fortress neutralisation removes obstacles. Air superiority protects movement. Together, these tactical aims enable the rapid encirclement envisioned by Fall Gelb.

| Opposition |

The plan triggers fierce opposition within the German command. Many senior officers view it as reckless. Some mock Halder as the gravedigger of the Panzer force. Critics warn that Ardennes roads are narrow and vulnerable. A single blockage could paralyse the advance. Supply lines would stretch dangerously.

Sceptics fear Allied reserves might not advance as expected. A strong counterstroke could trap the armoured spearhead. Logistics officers highlight the burden of sustaining multiple Panzer divisions. Fuel, ammunition, and maintenance present severe challenges.

These objections fail to prevail. Hitler and Halder argue that Germany’s position demands bold action. Britain and France grow stronger with each passing month. A cautious campaign promises only attrition. Even a limited chance of decisive victory seems preferable. The Manstein Plan becomes the final blueprint. Fall Gelb transforms into a high-risk operation.

As strategy settles, preparation intensifies. Hitler selects early May 1940 for the invasion. Spring mud must first subside. Operations in Denmark and Norway briefly divert attention. The build-up for Fall Gelb continues without interruption.

| Logistical and Political Preparations |

Executing Fall Gelb requires more than operational design. It demands large-scale logistics and political coordination. Behind frontline units stands an extensive mobilisation effort. German authorities focus on arming, fuelling, and supplying the force. Command structures also prepare to manage a complex war.

After the Polish campaign ends in September 1939, the army redeploys west. Dozens of divisions move by rail. Trains criss-cross Germany during October and November. Units concentrate along the French frontier and the Rhine Ruhr region. Divisions returning from Poland require refitting. Tanks and vehicles undergo repair after heavy use. Long road marches accelerate wear.

Ammunition stocks need urgent replenishment. Luftwaffe bomb expenditure in Poland reaches roughly one third of reserves. This triggers increased production during the winter. Armaments factories prioritise munitions and replacement equipment. Tank output increases, especially Panzer III and Panzer IV models. Deliveries remain limited but meaningful. Panzer regiments receive additional modern vehicles by spring 1940.

The army reorganises its structure. Four light divisions convert into Panzer divisions. New formations, including the Tenth Panzer Division, activate. Civilian lorries are requisitioned. Motor transport expands rapidly. More infantry and artillery gain mobility. These measures raise combat power significantly compared to autumn 1939.

Logistical planners prepare for rapid movement. Supply depots are established in the Rhineland. Fuel, ammunition, and rations stockpile close to the frontier. Fuel receives special attention. Mechanised warfare consumes petrol at extreme rates. Dumps are established west of the Rhine and in the Eifel. These reserves support sustained armoured operations.

Engineer units prepare bridging equipment. Pontoon bridges and assault boats are allocated. Special bridging trains support Army Group A. Pre-war exercises refine rapid river crossing techniques. At Sedan, engineers will later erect bridges within hours. Signals units plan communications to sustain mobile supply columns. Logistics planning focuses on speed and flexibility.

Railway troops prepare to exploit captured networks. Lines in Luxembourg and Belgium are targeted for rapid repair. Track conversion to German gauge follows closely behind the advance. Supplies move forward by rail as soon as possible. This prevents armoured spearheads from outrunning logistics.

Industrial mobilisation accelerates during winter 1939 to 1940. Germany is not yet on a full war economy footing. Key sectors nonetheless expand output. Aircraft production increases steadily. Fighter and bomber strength remains high despite losses. New Luftwaffe units form and re-equip.

Ammunition production expands across multiple calibres. Infantry divisions receive additional anti-tank guns. Artillery regiments are filled with new howitzers. Bridging equipment, radios, and trucks roll off production lines. Electronics output becomes especially important. By May 1940, nearly every German tank carries a radio. This capability multiplies battlefield effectiveness.

Fuel imports remain critical. Oil and raw materials arrive from Romania and the Soviet Union. These deliveries occur under existing trade agreements. Reserves accumulate ahead of the offensive. Without these imports, mechanised operations would stall.

Command coordination remains complex. The Army High Command manages operational planning. The Armed Forces High Command links military planning to Hitler. Tensions persist between institutions. Hitler intervenes frequently. He sets strategic objectives and approves major concepts. He endorses the Ardennes plan and airborne operations.

Hitler visits headquarters and frontline units. He exhorts commanders personally. He frames the coming battle as decisive. Staffs finalise coordination details. The invasion hour is fixed at dawn on 10 May. The Norway campaign is timed to avoid disruption. Final directives are issued on 9 May.

Diplomatically, Germany maintains deception. Assurances are given to neutral states until the last moment. Belgian and Dutch neutrality is publicly respected. Surprise remains the priority. Internally, Hitler suppresses doubts among senior officers. He insists that failure is unacceptable.

Training continues throughout the winter. Weather limits large manoeuvres. Small-unit exercises proceed constantly. Troops rehearse river crossings and combined-arms tactics. Panzer crews train with infantry. Air-ground coordination receives special emphasis. Stuka support procedures are drilled repeatedly.

Staff war games refine operational timing. Coordination problems are addressed. Combined-arms proficiency improves markedly. Confidence grows among the troops. Victories in Poland and Norway strengthen morale. Propaganda reinforces belief in success.

Anxiety remains among some commanders. Risks are clearly understood. Outward confidence prevails. By early May 1940, preparation is complete. The German military stands ready. At dawn on 10 May, Fall Gelb begins.

| German Forces for Fall Gelb |

By May 1940, Germany assembles a large and carefully organised force for the western invasion. The Wehrmacht structures its forces into three army groups. Luftwaffe air support integrates closely with ground operations. Specialised units attach at critical points. The German Army fields roughly 136 divisions for the campaign. These include ten Panzer divisions, eight motorised divisions, two airborne divisions, and over one hundred infantry divisions.

Army Group A under General von Rundstedt forms the main striking force. It deploys forty-five and a half divisions. Seven Panzer divisions operate within its command. Most German armoured and motorised strength concentrates here. Army Group A controls the Fourth, Twelfth, and Sixteenth Armies. It also commands Panzer Group Kleist under General Ewald von Kleist.

Armoured units organise into fast-moving corps. The XIX Panzer Corps under Heinz Guderian includes the First, Second, and Tenth Panzer Divisions. It also includes the motorised Großdeutschland Regiment. The XLI Panzer Corps under Reinhardt fields the Sixth and Eighth Panzer Divisions. The XV Panzer Corps under Hoth operates with the Fourth Army. It includes the Fifth and Seventh Panzer Divisions.

These seven Panzer divisions field around 2,400 tanks. Equipment includes Panzer I and II light tanks. Newer Panzer III and Panzer IV models appear in increasing numbers. Motorised infantry and regular infantry follow behind. Their role is to widen and hold the breakthrough. Army Group A’s mission is decisive. It advances through the Ardennes. It crosses the Meuse at Sedan, Monthermé, and Dinant. It then drives west to the Channel. The aim is encirclement of Allied forces in Belgium.

Army Group B under General von Bock forms the northern force. It deploys twenty-nine and a half divisions. Three Panzer divisions operate under its command. The Sixth Army under Reichenau and the Eighteenth Army under Küchler lead the advance. Their task is the invasion of the Netherlands and northern Belgium.

Armoured strength remains limited. The XVI Panzer Corps under Hoepner includes the Third and Fourth Panzer Divisions. They operate in Belgium with the Sixth Army. The Ninth Panzer Division supports the Netherlands advance with the Eighteenth Army. After the opening phase, some armoured units later transfer south.

Army Group B also includes elite motorised formations. These include the SS-Verfügungsdivision and attached SS regiments. The First Cavalry Division operates in the flat Dutch terrain. Army Group B attacks directly into the Low Countries. It engages Dutch forces and draws Allied armies north. British and French units advance into Belgium under the Dyle Plan. Army Group B assaults fortified border positions. It seizes major cities rapidly. Its role is diversionary. The main blow falls further south.

Army Group C under General von Leeb guards the southern front. It deploys nineteen divisions. The First Army faces the Maginot Line in Lorraine. The Seventh Army holds the Upper Rhine and Alsace. These formations consist mainly of infantry. Armoured strength is negligible. Their mission is defensive. They pin French forces in place. French units remain tied to their fortifications. Army Group C conducts no major offensive during Fall Gelb. Its attack follows later during Fall Rot.

The Luftwaffe plays a central role in the campaign. Two air fleets support the operation. Luftflotte Two operates under Albert Kesselring. Luftflotte Three operates under Hugo Sperrle. Together they commit around 1,800 combat aircraft. These include fighters, bombers, and dive bombers. They also deploy nearly 500 transport aircraft. Around fifty DFS-230 gliders support airborne assaults.

Kesselring supports Army Group B. Sperrle supports Army Group A. Initial tasks focus on air superiority. Allied air forces are targeted immediately. Rail hubs and communications are bombed. Ground forces receive direct close air support. The Ju 87 Stuka becomes central to the campaign. It attacks bunkers and artillery positions precisely.

Germany enters the campaign with ten Panzer divisions. This marks a significant expansion since Poland. Light divisions convert during the winter. A new Tenth Panzer Division forms. Each Panzer division combines armour, infantry, artillery, engineers, and reconnaissance. Tank strength averages around 300 vehicles per division.

Most tanks remain light models. Panzer III and IV numbers increase steadily. Allied tanks often possess thicker armour. Some mount heavier guns. German advantage lies elsewhere. Radios equip nearly every tank. Command and control prove superior. Training emphasises initiative and speed. Coordination with air power is routine. Leadership is aggressive and flexible.

Airborne forces represent a major innovation. The 7. Flieger-Division operates as a parachute force. The 22. Luftlande-Division follows by transport aircraft. Both operate under Luftflotte Two. Their mission is to seize key objectives early. Paratroopers and glider troops capture bridges and airfields. These actions support Army Group B’s advance.

Special forces also play a role. The Brandenburger Regiment and Infanterie-Batallion zBV 100 conduct covert operations. These commandos operate under military intelligence. They train in sabotage and deception. Many speak local languages fluently. They infiltrate before the main assault. Some wear enemy uniforms. Others pose as civilians.

By early May 1940, the German order of battle stands complete. Infantry, armour, air power, and special forces align. Logistical preparations near completion. The force awaits the signal to attack.

| Final Preperations |

By the second week of May 1940, the German Wehrmacht completes one of the most elaborate military build-ups in history. In eight months, planners transform Fall Gelb from a conventional offensive into an audacious sickle cut manoeuvre. The revised plan promises surprise and decisive results.

German army groups take their final positions. Army Group B stands in the north. Saboteurs already infiltrate the Netherlands and Belgium. Army Group A waits concealed in the Ardennes. Its armoured forces prepare to strike. Army Group C faces the Maginot Line. It maintains a quiet and fixing front.

Airfields across northern Germany and the Rhineland fill with aircraft. Bombers and fighters stand fuelled and armed. Crews prepare for the opening strikes. The Luftwaffe readies full-scale operations.

Paratroopers and glider troops rest uneasily during the night of May 9th, 1940. They expect airborne assaults before dawn. Many know they will enter combat within hours. German commanders conduct final briefings under lamplight. Intelligence summaries and weather reports are reviewed. The forecast predicts clear skies and favourable flying conditions.

Adolf Hitler remains awake at his headquarters. He monitors the hours passing. He watches for signs of Allied discovery. None appear.

The German command structure stands ready. Forces, logistics, and timing align. Operation Fall Gelb is about to begin.

| Multimedia |