| Page Created |

| March 23rd, 2023 |

| Last Updated |

| March 23rd, 2023 |

| Country |

|

| Additional Information |

| Unit Order of Battle Commanders Operations Equipment Multimedia Sources Interactive Page |

| Badge |

| – |

| Motto |

| – |

| Founded |

| 1940 |

| Disbanded |

| 1945 |

| Theater of Operations |

| Pacific Northwest Europe |

| Operational History |

The first use of Code Talkers in military history dates back to the final days of World War I in October 1918. During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, a brutal campaign to reclaim a German-held position, Allied troops relied on communication technology that was still in its early stages. Open radio frequencies and telephone lines were commonly used to transmit important military intelligence.

In 1918, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive in the last days of World War I, eight Choctaw soldiers serving as telephone operators realized they had stumbled upon a coded communication gem. They spoke a language so rare and complex that it was highly unlikely that anyone in Europe would understand it. The Choctaw Telephone Squad quickly realized that speaking in their mother tongue would enable them to share military intelligence swiftly and securely. The intricate phonetics and syntax of the Choctaw language made it nearly impenetrable to cryptographic reverse engineering.

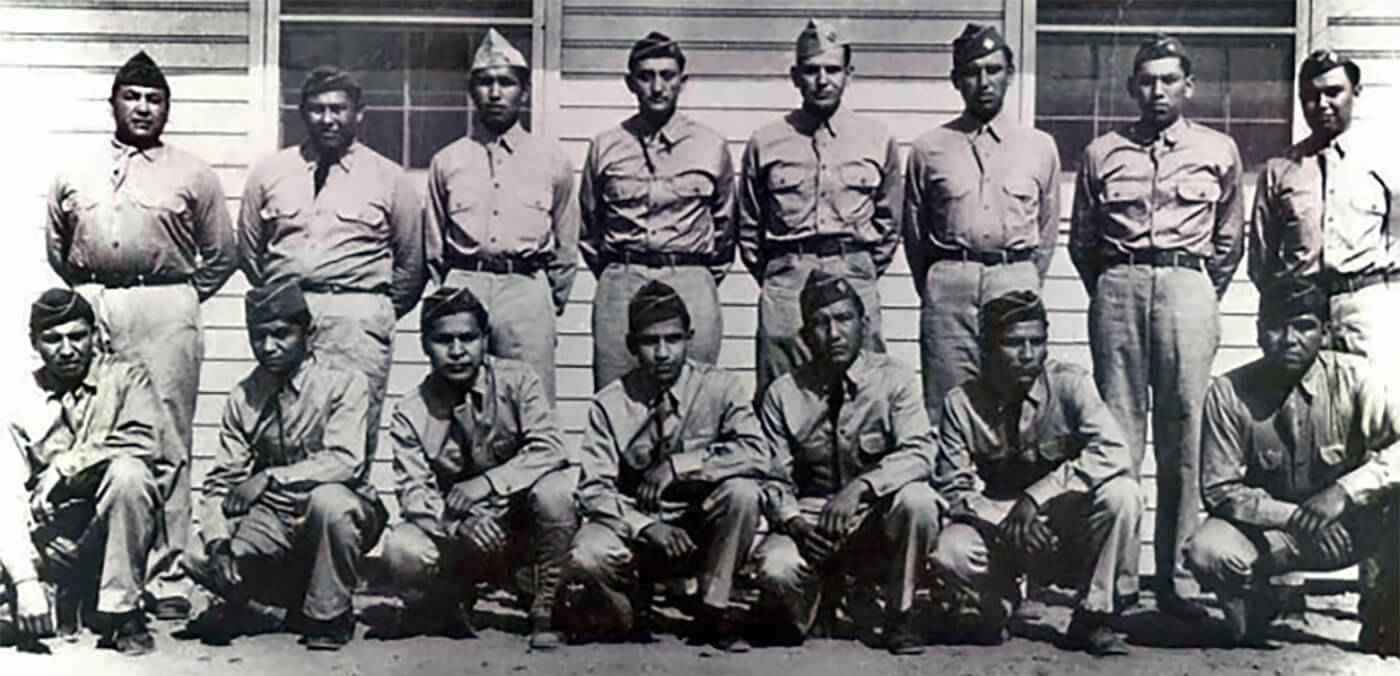

At the outset of World War II, American commanders are hesitant to utilise Native American troops as Code Talkers due to concerns that the Germans may have learned their language during the interwar years. However, as early as 1940, some Army units begin recruiting American Indians in Oklahoma specifically to train them as Code Talkers. Members of various tribes, including Comanches, Choctaws, Hopis, and Cherokees, were enlisted to send and receive messages in their native languages. Though other branches of the military were initially hesitant to follow suit, World War I veteran Philip Johnston, who had grown up on a Navajo reservation in Arizona and learned some of the Navajo language as a child, convinced them otherwise. Recognizing the complexity of Navajo and its utility on the battlefield, Johnston knew it would be difficult to break for non-speakers. In 1942, he suggested to the Marine Corps that Navajos and other tribes could be valuable for battlefield communications. After witnessing a demonstration of messages sent in Navajo, the Marine Corps was so impressed that they immediately recruited 29 Navajo men to develop a code using their own language, thus giving rise to the Navajo Code Talkers in the Marine Corps. Before long, Code Talkers from other tribes and nations were recruited for similar tasks in other branches of the military, ultimately becoming an integral part of every theater of the war until its conclusion.

Different Native American men who spoke various tribal languages faced unique challenges as Code Talkers, in order to convey essential military messages. Some tribal languages were capable of more direct translations, and these coding systems were called Type Two Codes. In such cases, a Code Talker could simply translate phrases like “C Company is moving east at 0830 in the morning” or “B Platoon needs more ammunition to their foxholes” directly and convey them over the radio. However, Navajo Code Talkers, as well as Code Talkers from the Comanche, Hopi, and Meskwaki tribes, had to develop a special code based on their languages, which was known as Type One Codes.

To develop their Type One Code, the original 29 Navajo Code Talkers had to assign a Navajo word for each letter of the English alphabet. Since this code would have to be memorized, the men chose words that were already familiar to them, such as words referring to animals. For example, the English letter D became the Native word for dog, while O was the word for Owl. The original 29 Navajo Code Talkers also had to develop special words for terms relevant to essential military equipment, including types of planes, ships, and weapons. The group was given picture charts showing these essential items, and they developed words that seemed to best fit the picture shown. For example, the Navajo word for eagle was used to represent a transport plane, while a destroyer was coded as a shark, battleship as a whale, cruiser as a small whale, submarines as iron fish, and a carrier as a bird carrier. Similarly, Comanche, Choctaw, and Hopi Code Talkers developed their own Type One Codes.

Aside from learning these codes, Code Talkers also had to receive proper training in handheld radio and field telephones, as well as other signaling equipment and electronic communication lines, to ensure that their messages could be technically transferred, no matter what. As Marines, the Navajo Code Talkers received their training at Camp Pendleton in California. With their codes developed and their training completed, Code Talkers increased their numbers and prepared for service on the front lines.

After completing their training, Navajo Code Talkers were deployed with Marine Corps units to transmit coded messages on battlefields throughout the Pacific theater. The first Code Talkers saw action on Guadalcanal, and their success led to the deployment of Code Talkers from other tribes, including Hopi, Comanche, and Meskwaki, to theaters like Europe and North Africa. By the end of the war, Code Talkers from various tribes served around the world.

In the field, a Code Talker would use a portable radio to transmit messages in their Native language, which would then be translated into English by another person. The Navajo Code Talkers were particularly skilled, translating three lines of English in just 20 seconds, a significant improvement over existing code-breaking machines that took 30 minutes. This speed allowed for essential messages to be conveyed quickly, saving valuable time on the battlefield.

Throughout the war, over 420 Navajos served as Code Talkers, making them the largest group of Native Americans to serve in this capacity. These men served heroically under fire, delivering their coded messages in all situations, including during battles like Iwo Jima and Okinawa. During the month-long battle on Iwo Jima, six Navajo Code Talkers transmitted over eight hundred messages without error. After the battle, a signal officer from the 5th Marine Division declared that without the Navajos, the Marines would not have taken Iwo Jima. By the end of the war, eight Code Talkers had lost their lives, but their code remained unbroken, a testament to the bravery and gallantry of these remarkable men.