| Page Created |

| April 24th, 2022 |

| Last Updated |

| July 17th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| New Zealand |

|

| Rhodesia |

|

| Additional Information |

| Unit Order of Battle Commanders Operations Equipment Multimedia Mulimedia 2 Multimedia 3 Sources Biographies |

| Badge |

|

| Motto |

| Non Vi Sed Arte Not by Strength by Guile |

| Founded |

| July 3rd, 1940 |

| Disbanded |

| August 1st, 1945 |

| Theater of operations |

| North African Desert *Egypt *Libya *Sudan Greece * Dodecanese Islands Albania Yugoslavia Italy |

| Organisational History |

The Long Range Desert Group is the brainchild of Ralph Bagnold. Bagnold had worked in the North African Desert as geologist and desert explorer in the 1930’s. His research group was one of the first to use motorised vehicles for desert exploration. While being in the desert they experimented with new ways to navigate and drive in the unforgiving North African Desert.

Bagnold’s Expedition in 1929

When the war in the North African Desert broke out Bagnold was in Cairo, Egypt. Realising his unique skills could make a difference in the North African Theater he requested a meeting with General Archibald Wavell, the Commander-in-Chief of the Middle East. His request was granted, and they met on June 23rd, 1940. During the meeting Bagnold explained his concept of long range reconnaissance patrols that would drive deep into the North African desert to gather information and observe the Italian army. The information they gather would be radioed to the British Headquarters. Besides the intelligence task Bagnold also suggested the unit could commit “acts of piracy”.

Wavell understood Bagnold’s concept and gave him permission to raise a unit like he described. When Italy declared war on June 10th, 1940, Wavell urgently needed more intelligence on the enemy’s plans, potential paths of attack, and available forces. Aerial reconnaissance was not enough, and Bletchley Park’s codebreaking efforts had not yet provided much useful information. Traditional ground reconnaissance could only gather information on units in the front area. The new Long Range Patrol Unit was intended to fill in the gaps in intelligence.

On July 3rd, 1940, the Long Range Patrol (LRP) is founded. Bagnold is more or less free to recruit whoever he wants. In July 1940, the Provisional War Establishment includes provisions for eleven officers and seventy-six other ranks with forty-three vehicles. His idea is to use men from the Australia or New Zealand. He believes their outdoor kind of living would give them a natural advantage in the North African Desert. Australia refuses but New Zealand is happy to oblige Bagnold’s request. He is allowed to select his men from the 2nd New Zealand Division. Since half of the division volunteers, he has no problems in selecting his troops. In the end he selects two officers and sixty-seven non-commissioned officers and soldiers. Besides these men eighteen administrative and technical personnel are selected for the unit.

After selection, the unit undergoes a strenuous six-week training after which they are inspected by General Wavell and declared ready for action, as the No.1 Long Range Patrol Unit. Their first training patrol followed in August of 1940.

The first training patrol is led by Bagnold, who embarks with two Ford WB trucks, five New Zealanders, and an Arab guide. Their objective is to monitor supply traffic along the track between Jalo and Kufra. Concurrently, Shaw utilises other patrols to establish supply depots along the Libyan border. These depots are crucial for sustaining operations due to the vast distances that would need to be covered later on.

On September 13th, 1940, the unit establishes its inaugural base in the Siwa Oasis. They reach this destination by traversing approximately 240 kilometres across the Egyptian sand desert.

On October 1st, 1940, the unit moves the Isolation Hospital in Abbassia, near Cairo in Egypt as its new headquarters. On October 10th, 1940, the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary force request fot the return of their personnel. The men are allowed to stay for the time being.

On November 11th, 1940, permission is granted to double the size of the unit, and the revised establishment allowed for twenty-one officers and 271 other ranks, consisting of a headquarters and two squadrons each with three fighting patrols equipped with a total of ninety vehicles. Meanwhile on December 4th, 1940, the unit moves to Camp Maadi near Cairo.

On December 5th, 1940, with the first Guardsmen of Guards (G) Patrol start arriving. G Patrol is formed from the Coldstream Guards and 2nd Battalion Scots Guards under the leadership of Captain Pat Clayton and Major Crichton-Stuart. Comprised of 31 Non-Commissioned Officers and Guardsmen, the unit initially recruits eighteen volunteers from each regiment. Remarkably, these volunteers sign up without knowing much about the unit beyond its reputation as a fighting force.

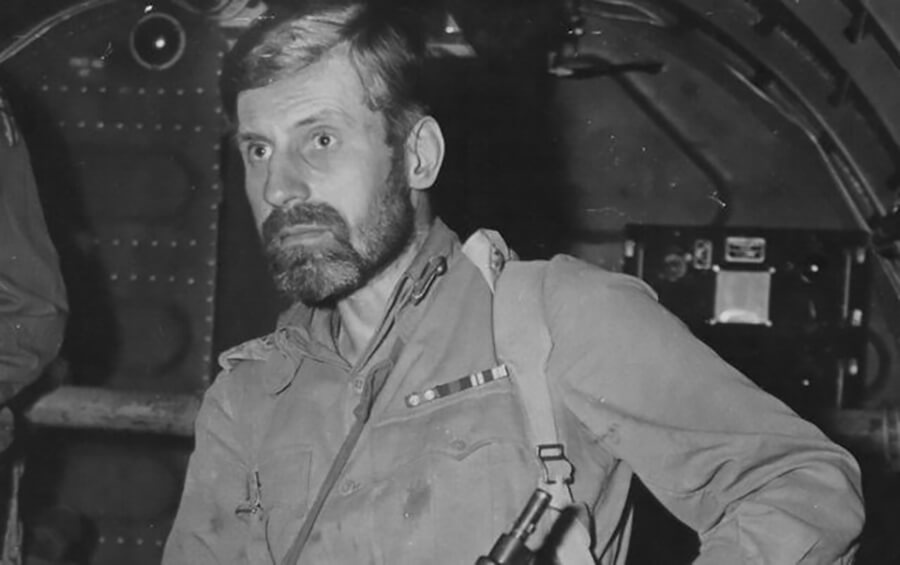

On October 17th, 1940, Major Orde Wingate arrives in the Middle East with a plan for a large force, approaching the size of a division. The mission of this force would be to disrupt enemy operations in the rear area through actions from bases in the Tibesti area. This force would rely on air resupply to remain mobile and independent of conventional logistics, with the ultimate goal of defeating major enemy units. Despite its ambitious nature, Wingate’s plan is seriously considered in Great Britain and receives a hearing at GHQ Middle East, with the condition that “their desert man,” Bagnold, evaluates the plan.

Major Orde Wingate

Bagnold realises that Wingate’s idea was good in theory but lacked the understanding of terrain, vehicle payloads, fuel consumption, and the air and ground transport available to the resource-strapped Middle East command. He writes a memo for a modified Wingate plan based in part on Stage III of his own original concept. Stage I is reconnaissance and harassment. Stage II involves expanding operations to include cooperation with the Free French in order to gain their recognition as a viable ally and demonstrate to the Arab people that the Italians were not in control of their annexed territory. Stage III calls for the expansion of the Long Range Patrol Unit into a desert mechanised force with its own integral artillery, light armor, and infantry based on portees and 10-ton trucks, as well as an air component for close air support and reconnaissance. These units would operate independently and only combine for specific operations before dispersing again. The plan, is presented with clear data and conclusions, is well-argued but many of its demands, particularly in terms of exclusive air support and manpower, are more than General Headquarters is willing to provide. As a result, Wingate is sent to lead “Gideon Force” in Eritrea.

On December 26th, 1940, Boxing Day, G and T Patrols embark on the Murzuk Raid, joined by French allies, totaling 76 men and 23 vehicles. Their destination Murzuk, is an Italian fort located 1609 kilometers from Cairo, necessitating a grueling 2414-kilometer journey lasting 18 days.

On January 3rd, 1941, the Rhodesian (S) Patrol is raised and the Yeomanry (Y) Patrol on March 9th, 1941. The sixth patrol is never formed, and the authorisation is used instead to create the Royal Artillery Section. This takes place on March 21st, 1941, with the activation of the Royal Artillery H Section. Y Patrol was primarily composed of members from the regiments of the 1st Yeomanry Division. The original Y Patrol comprises mainly men from Yeomanry Regiments, with only a few exceptions. These exceptions include Second Lieutenant Easonsmith from the Royal Tank Regiment, the patrol sergeant from the Royal Scots Greys, and ancillary support personnel such as the fitter, W/T (wireless telegraphy operator), and the medical officer. However, the composition of Y Patrol undergoes a significant change starting from September 1941. From that time on, several members from the 11 Middle East Commando Scottish Commando join their ranks. This reinforces Y Patrol, diversifying its composition.

Bagnold implements a modified Bagnold plan acquiring 10-ton trucks for desert trials and forming a small artillery and tank contingent within the Long Range Desert Group in August 1941. Bagnold is promoted to “Inspector of Desert Troops” in August 1941 to plan the creation of additional desert Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol units, with Group command passing to his second-in-command, Guy Prendergast of the Royal Tank Regiment. The Indian Long Range Squadron is the only unit that resulted from this move before interest in special desert units decreased and Bagnold returns to his old job in signals, effectively losing any further control over deep desert operations.

In August 1941, the Squadrons are restructured. G and Y Patrols now form B Squadron, the remainder of the patrols form A Squadron.

During the end of October and the beginning of November 1941 the Patrols are reorganised into half patrols. This effectively means that every patrol is now spilt in 1 and 2.

By March 1942, the Group reaches its full strength of twenty-five officers and 324 other ranks, including 36 Signals personnel and 36 Light Repair personnel, as well as 130 vehicles. The Indian Long Range Squadron (ILRS) consisted of 7 British officers, 9 British other ranks, 3 Indian officers, and 82 Indian other ranks, organised into a headquarters and two patrols each comprising two half-patrols with thirty-five vehicles like those of the Long Range Desert Group, although the armament is different. From May 11th, 1942 until the end of July 1942 the two patrols from the Indian Long Range Squadron (IRLS) are attached to the Long Range Desert Group.

From June 1941 to August/September 1941, G, H, and Y Patrols are the first three, with H Patrol being a half patrol of eighteen men, consisting of nine men from Y Patrol and nine men from G Patrol. The second set of three patrols, S, T, and R were complete patrols. It’s important to note that H Patrol did not stand for Heavy Section during this period.

By November 1941, the patrols are split into half patrols. G1 is led by Captain Hay, G2 by Lieutenant Timpson, R1 by Captain Jake Easonsmith, R2 by Second Lieutenant Browne, S1 by Captain Holliman, S2 by Second Lieutenant Olivey, T1 by Major Ballantyne, T2 by Captain Hunter, Y1 by Captain Simms, and Y2 by Captain Lloyd Owen.

Between

October 1st, 1942, and April 3rd, 1943, the ILRS in its entirety is attached to the Long Range Desert Group and falls under the command of the Group’s Headquarters.

| Tunisia |

October 23rd, 1942 is remembered as the night the Battle of Alamein begins. Almost exactly three months later, General Montgomery and the Eighth Army enter Tripoli. This great advance immediately impacts the Long Range Desert Group, as the Road Watch resumes its importance, and Kufra becomes too far back for the base, necessitating a forward move. Additionally, there is a significant need to replace men and vehicles lost during the raids of the previous month.

The Yeomanry Patrol, which had been to Tobruk, remains intact and ready for operations. Captain Spicer of the Wiltshire Yeomanry takes over after the previous commander is evacuated to a hospital in Cairo. They are sent back to Marble Arch on October 30th, 1942, for another Road Watch and are present during the early stages of Montgomery’s advance.

By November 10th, 1942, it becomes clear that the number of vehicles reported daily increases from under a hundred in each direction to about 3,500 heading west, with virtually none going the other way. This indicates Rommel’s retreat from Cyrenaica, further confirmed by reports of lorries full of Italians moving back towards Tripoli.

The New Zealanders, who take over from the Yeomanry Patrol, face challenges as it becomes apparent that the enemy is preparing defences near their watch positions. Thousands of vehicles are dispersed near Marble Arch, and working parties come dangerously close. Consequently, they are pulled out, and a Guardsmen Patrol is sent forty miles farther west to re-establish the Watch. This task becomes increasingly important and challenging as enemy activity intensifies.

The enemy becomes aware of the routes used by the Long Range Desert Group and begins patrolling and mining these routes, causing increased distances for Patrols. Due to these difficulties, Guy Prendergast duplicates the Patrols to ensure the road remains under observation.

Alastair Timpson, recovered from injuries, encounters significant trouble on his way to duty. In the gap between Marada and Zella, he faces an enemy patrol of eight vehicles, including two armoured cars. To avoid contact, he attempts a detour but finds his path blocked, forcing him to engage in combat. Despite efforts to conceal and dismount some guns, the enemy proves too strong, and Timpson only manages to save a Jeep and two trucks. However, he retains his wireless truck, which allows him to report the situation to Group Headquarters. He learns that the New Zealand Patrol parallel to him ran into a minefield and had to return to Kufra. He is instructed to maintain the road watch at all costs, which he remarkably does from a spot only four hundred yards from the road for the next two weeks, despite numerous hardships.

Continuous enemy activity forces frequent relocations, and the Patrols endure rain, cold, and lack of sleep. They persevere until a Rhodesian Patrol establishes a position farther west. Subsequently, Ron Tinker and his New Zealand Patrol take over from the Rhodesians as the enemy withdraws from Buerat-el-Hsun on December 26th, 1943. Tinker finds himself surrounded by enemy forces and has to find a new campsite. During relocation, armoured cars discover his position, causing further dispersion of his men and loss of six individuals, though two later rejoin.

As the Eighth Army advances rapidly, the imperative necessity for the Road Watch diminishes, and it is called off. An official assessment by the Director of Military Intelligence at General Headquarters in Cairo praises the Long Range Desert Group Road Watch for its exceptional accuracy and indispensable reports, critical for calculating enemy strength and intentions during periods of enemy withdrawal or reinforcement.

Many other tasks pour in for the Long Range Desert Group, mostly related to reconnaissance for future Eighth Army moves and transporting agents. The Long Range Desert Group joins forces with General Leclerc and the Free French in Chad to assist in their advance towards the Fezzan. A Rhodesian Patrol performs invaluable work with the French, including provoking enemy retaliation at Gatrun, leading to the destruction of an enemy aircraft.

The Long Range Desert Group’s knowledge of the terrain ahead of the Eighth Army becomes crucial, demonstrated when Tony Browne leads the New Zealand Division and the 4th Light Armoured Brigade to outflank the El Agheila position at the end of December. Browne’s efforts result in significant enemy losses and valuable reconnaissance, though he sustains injuries when his truck hits a mine.

Throughout early 1943, Long Range Desert Group Patrols, including Indian Patrols of the Indian Long Range Squadron, continue to gather critical intelligence and support the Free French. However, the enemy becomes more aware of their activities, leading to increased difficulties and unfriendly reactions from Tunisians influenced by Axis propaganda.

David Stirling, founder of the Special Air Service, expands his operations despite enemy threats, but his capture in Gabes Gap marks a significant loss for the Allied forces. Despite this setback, the Long Range Desert Group continues its missions, with Bernard Bruce undertaking arduous reconnaissance in Tunisia.

Ron Tinker’s New Zealand Patrol plays a crucial role in guiding the New Zealand Division’s left hook to the Mareth Line, significantly aiding the Eighth Army’s advance. By mid-1943, with the Axis forces in Tunisia defeated, the Long Range Desert Group prepares for a new role in Europe, transitioning from desert operations to shorter-range missions in diverse terrains.

In early 1943, the Long Range Desert Group enjoys a period of respite by the Mediterranean, preparing for future missions while awaiting further instructions from General Headquarters in Cairo. The transition involves adapting to new methods of subversive warfare suitable for the European theatre, indicating a significant change in the Long Range Desert Group’s operational approach.

| Reassignment |

The new charter for the Long Range Desert Group specifies that it organise into small Patrols capable of maintaining communications while operating on foot for a distance of a hundred fifty kilometres behind enemy lines. They are to carry sufficient food on our backs for ten days, in case resupply is delayed. Language training in German and Greek is essential, so they can communicate with local people to fulfil their basic needs. Additionally, they retain a proportion of Jeeps for use when penetration through the lines is feasible.

There is a lot to be done, and they are in a hurry. They all understand that the longer it takes to readjust our methods and become proficient with new techniques and equipment, the longer they will be out of active operations. They believe passionately that they still have valuable contributions to make towards the successful outcome of the war.

Doc Lawson, the Long Range Desert Group Medical Officer, is tasked with reforming the unit to be more suitable for physical duties. Readjustment brings various repercussions, especially for the officers and men. Those who excelled as vehicle gunners may not be as effective on foot. Sadly, the Long Range Desert Group has to say goodbye to some who do not fit into the new structure. so, one of the goals is eliminating individuals less suiatable for the new job. Training begins with three-hour walks without packs, progressing to walks with empty packs, and eventually working up to 18 kilograms with two-day trips by the end of the month.

As the men adapt, training intensifies, which starts each morning at 05:45 hours and ends at 2000 hours. Each week, they march with heavier packs over longer distances, eventually covering 130 to 160 kilometres with 25 to 35 kilograms packs across mountainous terrain against the clock. They experiment with clothes, equipment, and weapons, finding the American Winchester .300 carbine preferable to the heavier Lee-Enfield .303 rifle. Footwear preferences vary, with some soldiers choosing Arctic Knee boots, others American combat boots, and a few opting for South African brown leather boots.

Mules are found to be too conspicuous in the mountains, and patrols, initially consisting of an officer and eleven men, are deemed too cumbersome and reduced to seven. With many veterans returning to their former units during mountain training, the Long Range Desert Group must recruit anew. Lieutenant-Colonel Prendergast seeks soldiers who share common ideas and sympathies, friends as well as comrades, as they will spend much time in close proximity.

For officers, Lieutenant-Colonel Prendergast expects all of the qualitiesof enlisted men, plus a knowledge of men. He emphasizes that officers must live with their men, endure their hardships, and share their successes. They must be more expert than their men in handling weapons and equipment. Prendergast’s final requirement is crucial for both officers and men: he avoids those with a reputation for being “tough,” as such individuals often lack intelligence, initiative, discipline, and sometimes courage.

In May 1943, the Guards G1 and G 2 Patrols are disbanded and their men, along with those from the Heavy Section, are being used to form M 1 and M 2 Patrols of B Squadron alongside Y and S Patrols.

The unit’s structure remains essentially the same, with Lieutenant-Colonel Guy Prendergast leading the Long Range Desert Group and Jake Easonsmith as his deputy. Major Alastair Guild commands the New Zealand A Squadron of six Patrols, while David Lloyd-Owen takes command of a similar-sized B Squadron formed from British and Rhodesian troops. David Lloyd-Owen has not closely worked with the Rhodesians until now, but he quickly learns to appreciate their worth. They possess an inherent sense of initiative and the ability to thrive in adverse conditions.

Despite the scarcity of suitable equipment, Lieutenant-Colonel Prendergast’s knowledge and Easonsmith’s inventive genius overcome most problems. They scour store depots and captured enemy equipment dumps for ideas. For the rest of the,, the thought of carrying everything on our backs is strange, and our most urgent task is to get as fit as possible. The hot and listless air of Alexandria is hardly ideal for training.

B Squadron is the first to arrive at the Ski School on May 20th, 1943, followed a month later by A Squadron. The school, originally a hotel and ski resort at an altitude of 1,829 meters near the village of Becharré, is named after the small grove of the original Cedars of Lebanon nearby. Initially an initiative of the Australian Imperial Force, the ski school opens in December 1941 and quickly expands to include the Mountaineering Wing of the Middle East Mountain Warfare School near Tripoli. Jimmy Riddell, of Olympic ski fame, is running a mountain craft training school. Captain Griffith Pugh, serving as the Medical Officer, is also there, teaching rock-climbing and skiing.

The historic cedars outside our door provide an enchanting backdrop, especially as skiers weave among them. The rustle of skis on snow and the occasional clatter of sticks as someone falls, followed by laughter, creates a memorable atmosphere. Crisp, sharp nights add to the beauty, with the silence of the snow-covered landscape under a brilliant moon.

Training is rigorous, involving long marches with heavy packs, nights in the snow, and handling obstinate mules. They also study Greek and German, strip and fire our guns, load our Jeeps, cook lightweight rations, and operate new wireless sets. Finding our way accurately remains a cardinal rule.

New equipment, including sleeping bags, rucksacks, wireless sets, weapons, and boots, is constantly tested. Back in Egypt, Lieutenant-Colonel Prendergast and Easonsmith work tirelessly to secure necessary supplies. Despite their unconventional requests, they receive most of what they need, thanks to the efforts of the staffs in Cairo.

The summer of 1943 sees the Long Range Desert Group anticipating their next mission amidst rigorous training. With news of the Allied landings in Sicily and Sardinia, and the subsequent overthrow of Mussolini, speculation about future operations intensifies. As the Allies push the Germans from Sicily to the Italian mainland, Churchill’s attention shifts to the Aegean Sea, particularly the strategic islands of the Dodecanese, including Rhodes, Cos, and Leros. Easpeciaaly after the Italian armistice with the Allies on September 3rd, 1943,

Meanwhile, Lieutenant-Colonel Prendergast has arranged parachute training to extend the operational range of the unit. Volunteers respond magnificently, with only a few opting out initially. In early September, Jake Easonsmith takes a party for parachute training in Palestine.

After being declared unfit for jumptraining, David Lloyd-Owen takes a leave and travels to Palestine with Dick Lawson. Unexpectedly, orders for immediate deployment to an unknown destination arrive. With half of David Lloyd-Owen men in Palestine without operational equipment, while the rest of his squadron in Lebanon it’s a bit of a mess.

Despite the chaos, they manage to organise and embark from Haifa by evening. A Greek sloop takes them to Castellorosso, where they arrive on Spetember 13th, 1943. Settling into empty houses, they establish contact with Cairo and prepare for their mission.

| Leros |

The following afternoon, Major David Lloyd Owen receives a signal from Cairo instructing him to move his men north to Leros, approximately 275 kilometres away. General Headquarters has received intelligence that a German emissary has arrived to discuss surrender terms with the Italian garrison. Lloyd Owen is ordered to seize the island due to its natural harbour and well-sheltered seaplane base.

Major Lloyd Owen sends Captain Alan Redfern ahead in a seaplane while he arranges sea transport for the rest of his men. Captain Redfern, a dependable Rhodesian officer who joined the Long Range Desert Group only the previous April.

While Captain Redfern flies to Leros, Major Lloyd Owen commandeers an Italian motor launch, squeezing as many men as possible into the vessel, and orders the reluctant skipper to navigate past German-occupied Rhodes to Leros.

B Squadron of the Long Range Desert Group arrives on Leros on September 17th, 1943, Captain Redfern and an Italian admiral are there to meet them, although the admiral is less than impressed with the strength of the British invasion party.

A Squadron departs from Haifa on September 21st, 1943, ten days after B Squadron, sailing on the Greek destroyer Queen Olga in convoy with three other destroyers. They reach Portolago, Leros, during an air raid the following day. Despite the attack, minimal damage occurs, allowing immediate unloading of stores and the establishment of a camp at Alinda Bay on the island’s eastern side. A few days later, the Queen Olga and H.M.S. Intrepid are sunk at Portolago, and the naval barracks suffer significant damage from heavy air raids.

On September 25th, 1943, two A Squadron patrols set out from Leros to the Cyclades, a chain of islands southeast of the Greek mainland, to monitor enemy shipping and aircraft movements. T1 patrol heads to Kithnos, and M1 patrol goes to Giaros. Additionally, Rhodesian patrol S1 is dispatched to Simi, a small island near the Turkish coast, about 24 kilometres north of Rhodes, and M2 patrol is sent to Stampalia. The remaining Long Range Desert Group units, along with the Special Boat Squadron and some commandos, concentrate on the island of Calino, a few kilometres south of Leros.

Upon their arrival on September 25th, 1943, they receive a warm welcome from the Greeks, who had been under Italian occupation. The enemy has already begun air attacks on Cos, the only island with an airfield capable of protecting sea and land forces in the Aegean. However, the limited number of fighters on Cos cannot fend off the determined German air force for long. On October 3rd, 1943, the enemy invades Cos by sea and air, and despite the determined resistance of a battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, the garrison is overwhelmed the next day.

Troops on Calino, 10 kilometres away, receive no warning of the invasion. As a result, the Long Range Desert Group narrowly escapes losing a patrol. On September 28th, 1943, Captain Tinker sets out with a composite patrol of twelve men to investigate mysterious signalling to Turkey from Pserimo, a small island between Calino and Cos. The signaler, later found to be a Greek agent in British pay, is sent back to Calino for interrogation. The invasion fleet, consisting of merchant ships, landing craft, flak ships, and three destroyers, arrives at Pserimo before dawn on October 3rd, 1943, and commences the assault on Cos. Eighty enemy troops land at Pserimo to establish headquarters and dressing stations, unexpectedly encountering Tinker’s men, who retreat to the high ground under heavy fire. Enemy patrols search the island for two days, but Captain Tinker’s party is evacuated on October 4th, 1943, with only one man captured.

The Long Range Desert Group is ordered to counterattack Cos that night, but the order is cancelled. All troops on Calino, now considered indefensible, are instructed to return to Leros. Stores and troops are loaded onto every available craft, and a makeshift fleet departs from Calino in the evening. They reach Leros throughout the night and quickly unload, anticipating air attacks. A dive-bombing raid by fifty-five aircraft begins at 05:30, lasting four hours, sinking an Italian gunboat and several small craft, and destroying buildings and installations.

The Leros garrison comprises Headquarters 234th Infantry Brigade, a battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, a company of the Royal West Kents, and Raiding Forces (approximately 200 Long Range Desert Group men, 150 Special Boat Squadron men, and 30 commandos). The only anti-aircraft defences are 40-millimetre Breda guns and five coastal defence batteries, each with four 150-millimetres naval guns from British ships, all manned by Italians. Five Long Range Desert Group patrols are dispatched to these battery positions to bolster Italian morale and ensure they do not turn their guns on brigade headquarters. This task requires tact, patience, and occasionally force.

The Italian communication system, already inefficient due to demoralized signalmen, is further damaged by bombing. In the later stages before the invasion, the only reliable communications are Long Range Desert Group wireless links. Daily bombing attacks by up to sixty aircraft target the coastal batteries. On October 8th, 1943, the battery on Mount Marcello, where Y2 patrol is stationed, is put out of action. The next day, the battery on Mount Zuncona, east of Portolago Bay, where R1 Patrol under Lieutenant D.J. Aitken is stationed, is also disabled. Aitken’s patrol then withdraws to A Squadron headquarters. German landing craft are spotted entering Calino’s bays on October 10th, 1943, and the next day, coastal batteries from Leros shell the enemy. The Long Range Desert Group sends small teams to Calino to gather intelligence on enemy activity.

One New Zealander, Sergeant R.D. Tant, fails to return from such a mission. Captured by the enemy, he is taken from Calino to Cos but escapes to Turkey and returns to Leros after a fortnight. He is captured again during the island’s invasion by the same German Fallschirmjäger company. The loss of Cos airfield significantly impacts the defence of Leros and Samos, as merchant shipping cannot enter the Aegean without risking heavy losses without air cover. The Navy can only operate at night. It becomes clear that holding Leros and Samos indefinitely is unlikely without capturing Rhodes, an operation beyond the available resources in the Middle East. However, the Commanders-in-Chief of the three services decide to hold Leros and Samos as long as possible.

Destroyers, submarines, and smaller craft bring in troops, supplies, six 25-pounder guns, twelve Bofors guns (strapped to submarines), jeeps, trailers, mortars, machine guns, ammunition, wireless equipment, and other stores. Parachutes drop additional supplies. The garrison is reinforced by 400 men of the Buffs, survivors from three destroyers sunk by mines off Calino on October 24th, 1943, and a battalion of the King’s Own.

Patrols are stationed on outlying islands to monitor enemy shipping and aircraft movements, acting on information from T1 patrol on Kithnos. The Royal Navy sinks a convoy on October 7th, 1943, preventing an immediate assault on Leros. Captain C.K. Saxton and six men of T1 patrol, taken to Kithnos by an 18-ton caique of the Levant Schooner Flotilla, avoid detection by changing hiding places and moving at night. Their information proves invaluable, and they stay on the island for a month, despite the enemy’s knowledge of their presence. Sergeant J.L.D. Davis, with some knowledge of Greek, obtains reliable intelligence about enemy dispositions and shipping routes, earning the British Empire Medal for his conduct.

T2 patrol, five men under Second-Lieutenant M.W. Cross, is stationed on Seriphos, finding a suitable hideout with the help of a local Greek. They stay for three weeks without being detected, despite the enemy patrolling close by. The patrol reports enemy aircraft movements, leading to the successful interception of flying boats by Beaufighters. T2 is relieved by a British patrol and returns to Leros with three Greeks.

Lieutenant Aitken and seven men from R1 patrol spend seventeen days on Naxos, confusing the garrison by making long cross-country treks and receiving intelligence from friendly locals. They report a concentration of shipping in Naxos harbour, leading to an Royal Air Force attack that sinks two ships but costs two aircraft. The patrol rescues the pilot and navigator of a downed Beaufighter, smuggling them out under the enemy’s nose and returning to Leros on 6 November without casualty.

After capturing Cos, the Germans consolidate their position in the Cyclades, occupying many islands. T1 patrol plans to escape to Turkey by capturing a German caique or a local fisherman’s boat, but T2 patrol arrives to relieve them before they attempt the escape. Saxton’s patrol returns safely to Leros on October 23rd, 1943.

| Levitha mission |

The survivors of the German Olympos convoy, sunk by the Royal Navy, are stranded on the island of Astypalaia. These survivors, mostly members of the 9th Battalion of the 999th Division, become prisoners of the occupying Italians. The Long Range Desert Group M2 Patrol, under Captain K.H. (Ken) Lazarus, is also on the island to support the Italians and establish an enemy shipping and aircraft watch. On 14 October 1943, H.M.L.S. Hedgehog, a 60-ton steam trawler, is sent to resupply the Long Range Desert Group at Astypalaia. Commanded by Sub Lieutenant D.N. Harding, Hedgehog is also ordered to transport wounded German PoWs to Leros, along with ten unwounded officers and NCOs for interrogation. However, the vessel ends up with over fifty prisoners crowded on board. After developing engine trouble and being mistakenly fired upon by a British submarine, the Hedgehog reaches Levitha, where the German PoWs overcome their captors and request rescue. On 18 October, German paratroops land on Levitha, securing the island with minimal resistance.

Major General F.G.R. Brittorous orders the Long Range Desert Group to capture Levitha. The assault force, named “Olforce,” comprises forty-nine men divided into two sections, aiming to secure the high central ground overlooking the southern port. On 23 October, Olforce departs from Leros. Captain John Olivey’s Section 1 lands without resistance, while Lieutenant Jack Sutherland’s Section 2 faces rough seas and heavy equipment but manages to capture enemy positions by 05:00 hours on 24 October, suffering casualties.

At dawn on 24 October, German aircraft and reinforcements heavily bombard the Long Range Desert Group positions. Communications between the sections fail, and the Germans launch a coordinated counterattack, isolating the New Zealanders on the ridge. By mid-morning, resistance increases, and by the afternoon, the New Zealanders, short of supplies, struggle to hold their ground. Sutherland decides to surrender at 18:00 hours. The remaining Long Range Desert Group men are taken prisoner.

The lack of reconnaissance and underestimation of the enemy’s strength leads to the loss of forty-two specialist troops. The operation costs A (NZ) Squadron two men killed, two missing presumed dead, and B Squadron one man killed. Brigadier George Davy’s visit results in the replacement of Major General Brittorous and a return to more sensible strategies.

| Losing the Kiwi’s |

Following the disastrous Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) assault on Levitha, a reorganisation of the Group becomes necessary. Lieutenant Colonel Easonsmith convenes a meeting with the senior officers of A and B Squadrons to discuss the future direction of the Long Range Desert Group. The plan is to reduce the size of the patrols from an officer and 13 men to an officer and 7, while increasing the number of patrols in a squadron from 5 to 6. Meanwhile, a control centre and six operational patrols are to be maintained in the Aegean. During the discussion, it is recommended that, apart from the patrols stationed in the Cyclades Islands to monitor enemy invasion movements, the rest of the Long Range Desert Group should return to the Middle East. This move is aimed at training reinforcements and reorganizing the Group for future operations. On November 1st, 1943, it is decided to send Major Lloyd Owen back to the Middle East via submarine to re-equip and train new patrols.

Lieutenant General Bernard Freyberg, the New Zealand Forces commander, reports on October 29th, 1943, and November 1st, 1943, the urgent need for 25 reinforcements due to recent amphibious operations resulting in significant casualties, losing about one-third of the squadron. He notes the logistical challenge of coordinating from 3000 kilometres away, complicating immediate decisions and replacements.

The New Zealand government wants to be consulted before committing its troops to new theatres of war and decides to recall the squadron to maintain control over their forces’ deployment. On November, 2nd, 1943, the Prime Minister communicates that the New Zealand Squadron should be detached from its current role and placed under the direct control of the General Officer Commanding 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF), noting recent casualties.

General Sir Henry Wilson, Commander-in-Chief Middle East, states it is impossible to replace the New Zealand Squadron at short notice and requests they remain with the Long Range Desert Group until replacements can be trained. He highlights the squadron’s valuable contributions to ongoing operations and suggests replacing New Zealand personnel casualties with British personnel or sub-units until full replacements can be trained.

It is agreed that the New Zealand Squadron will remain with the Long Range Desert Group temporarily, with British personnel filling in for casualties. The squadron will be withdrawn as soon as the tactical situation allows. Freyberg conveys General Wilson’s appreciation for the New Zealanders’ valuable work and urges the New Zealand government to agree to the temporary retention and replacement plan to ensure continued operational effectiveness while preparing for the squadron’s eventual withdrawal.

On November 7th, 1943, only a part of A Squadron is withdrawn. Lieutenant D.J. Aitken with twenty men from R1 Patrol and A Squadron Headquarters including Major Guild leave for Palestine by destroyer. Around the same time, Major Lloyd Owen arrives in Cairo, just as the battle for Leros begins. On November 10th, 1943, he drafts an urgent message for the Fortress Commander, but bureaucratic delays prevent it from being sent in time, leading to tragic consequences.

| Battle for Leros |

In the early hours of November 12th, 1943, 15 German landing craft approach Leros under cover of darkness. The East Kent Regiment, known for their resilience and fighting spirit, valiantly repels most of the landings except at Grifo Bay. The Germans manage to establish two footholds on the island, setting the stage for a fierce battle.

By the afternoon, 40 Junker 52 aircraft drop 470 paratroopers, who are met with fierce resistance from the Allied forces, including the Long Range Desert Group and the Special Boat Squadron. Despite heavy casualties, around 200 German paratroopers land successfully. Major Redfern of the Long Range Desert Group is killed during the intense fighting, a significant loss as he is a respected leader.

On November 13th, 1943, the Germans fortify their positions and continue their assault. The British counterattack but face difficulties due to the relentless German air support and broken communications. The Germans isolate the northern and southern British defenses. The Long Range Desert Group patrols are sent to counter the German paratroopers, resulting in heavy skirmishes. Among the casualties is Alan Redfern, a well-liked and respected officer.

The next day, November 14th, 1943, British forces launch counterattacks to regain key positions but are met with heavy resistance. The Germans secure strategic points, and their relentless air raids weaken British morale and defenses. Lieutenant Colonel John Easonsmith, leading some men into the village of Leros to gather intelligence, is killed by a sniper’s bullet, a devastating blow to the Long Range Desert Group and all who knew him.

Despite reinforcements from Samos, British efforts to regain control falter by November 15th, 1943. The Germans launch a decisive assault on Meraviglia, supported by overwhelming air power. Brigadier Tilney, realizing the dire situation, contemplates a last-ditch effort to regroup, but it is too late.

At dawn on November 16th, 1943, the Germans launch a final, fierce attack on Meraviglia. Allied defenses crumble under the relentless assault, and Brigadier Tilney is captured. The island’s defenses collapse, and by evening, organized resistance ceases. Major Jellicoe of the Special Boat Squadron, seeing the hopelessness of the situation, orders his men to prepare for evacuation.

As night falls, Major Jellicoe and his men orchestrate a daring escape. They commandeer an Italian caique and a motorboat, evading capture and eventually reaching safety in Bodrum, Turkey. Meanwhile, scattered groups of Long Range Desert Group and other troops make perilous journeys to escape the island. Colonel Prendergast, Captain Croucher, Captain Tinker, and others, including members of R2 patrol, hide on Mount Tortore until they are evacuated on November 22nd, 1943.

On December 29th, 1943, A (New Zealand) Squadron is withdrawn from the Long Range Desert Group and replaced by A (Rhodesian) Squadron.

On June 21st, 1945, the members of the Long Range Desert Group are informed that the unit will be disbanded. On August 1st, 1945, the last men leave the unit finalising the disbandment of the Long Range Desert unit.