| Page Created |

| August 26th, 2022 |

| Last Updated |

| February 17th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Additional Information |

| Commandos Order of Battle Commanders Operations Equipment Multimedia Sources Biographies |

| Badge |

|

| Motto |

| – |

| Founded |

| June 1940 |

| Disbanded |

| 1946 |

| Theater of Operations |

| Northwest Europe Middle East North Africa Mediterranean Asia |

| Organisational History |

During the second Boer War between 1889 and 1902, the young Winston Churchill works in South Africa as a journalist for the Morning Post. Churchill, a former lieutenant in the British Army, first-hand witnesses the exploits of the Boer Kommandos. The Boer Kommandos are a mounted group of irregulars who lived of the land and used hit and run tactics to fight the British.

Shortly after his arrival, Churchill accompanied a scouting expedition in an armoured train that was reconnoitring the area between Frere and Chievely. On November 15th, 1899. the train was ambushed and partially derailed by a group of Boer Kommandos. Throughout the attack Churchill helps to organise and load wounded soldiers onto the still operational locomotive, which then managed to escape. Without any form of transportation and running out of supplies, the Boers capture Churchill, and his companions.

Even though Churchill is technically a civilian he is treated as a prisoner-of-war. He is taken to Pretoria and imprisoned in a converted school with British officers. Churchill does not have the intention to stay there and starts making plans to escape. On December 12th, 1899, he manages to escape from the camp and after some serious hardships he manages to reach the British lines.

After his escape Churchill stays in South Africa and takes part in the Battle of Spion Kop and the relief of Ladysmith. In the closing stages of the war, he, and his cousin the Duke of Marlborough ride into Pretoria and demand and receive the surrender of the guards of the prison camp. His time in South Africa will make a difference for specialised units when he becomes Prime Minister of Great Britain during the initial stages of World War 2.

When, in 1940, the Germans start the occupation of the Europe with enormous force of power, Great Britain is forced to retreat to the British Isles. Having suffered some major defeats on several fronts with heavy casualties, it becomes clear that the British are not able to attack the mainland for years. Churchill demands immediate raids to hinder the Germans and there are some early examples of some action. After the completion of the evacuation from Dunkirk on June 4th, 1940, Churchill writes to General Hastings Lionel Ismay: “We are greatly concerned—and it is certainly wise to be so—with the dangers of the Germans landing in England in spite of our possessing the command of the seas and having very strong defence by tighten in the air. Every creek, every beach, every harbour has become to us a source of anxiety. Besides this the parachutists may sweep over and take Liverpool or Ireland, and so forth. All this mood is very good if it engenders energy. But if it is so easy for the Germans to invade us, in spite of sea-power, some may feel inclined to ask the question, why should it be thought impossible for us to do anything of the same kind to them? The completely defensive habit of mind which has ruined the French must not be allowed to ruin all our initiative. It is of the highest consequence to keep the largest numbers of German forces all along the coasts of the countries they have conquered, and we should immediately set to work to organise raiding forces on these coasts where the populations are friendly. Such forces might be composed of self-contained, thoroughly equipped units of say one thousand up to not more than ten thousand when combined. Surprise would be ensured by the fact that the destination would be concealed until the last moment. What we have seen at Dunkirk shows how quickly troops can be moved off (and I suppose on to) selected points if need be. How wonderful it would be if the Germans could be made to wonder where they were going to be struck next, instead of forcing us to try to wall in the Island and roof it over! An effort must be made to shake off the mental and moral prostration to the will and initiative of the enemy from which we suffer.”

Churchill hand-picked General Hastings Lionel Ismay as his Chief Military Assistant and Staff Officer and in that role, he served as a Churchill’s liaison officer for the Chief of Staffs.

That very evening Lieutenant-Colonel Dudley Clarke, staff officer of the War Room, works out a plan for the formation of a raiding force. The force would be made up of 5,000 men, divided into ten independent units, which would carry out small frequent raids along German-occupied coasts. This would tie up German resources along the entire periphery of the occupied territories and hinder their efforts to build up an invasion force to attack Britain. Dudley Clarke’s South African roots makes him call the raiding force, Commandos.

This plan is passed on to Winston Churchill. It is more than likely that Churchill’s earlier encounter with the Boer Kommandos made him realise the intentions of Dudley Clake’s plan. Churchill’s initial name for the raiding force was Leopards but his experiences the second Boer War made him agree with the name Commando. He writes to the Chief of Staffs on June 6th, 1940: “Enterprises must be prepared with specially trained troops of the hunter class, who can develop a reign of terror first of all on the “butcher and bolt” policy to kill and capture the Hun garrison and then away. I look to the Chiefs of Staff to propose me measures for a vigorous, enterprising and ceaseless offensive against the whole German occupied coastline. Tanks and AFVs must be made in flat-bottomed boats, out of which they can crawl ashore, do a deep a raid inland, cutting vital communications, and then back, leaving a trail of German corpses behind them.”

Although this description did not appeal to a lot of the officers in British Army the Chief of Staffs approves the foundation of the raiding force. Dudley Clarke is promoted to a full Colonel and made head of a new section of Military Operations. The unit known as Military Operations 9 (MO9) is tasked with uniformed raids.

As early as June 9th, 1940, the requirements for the Commandos are stated as followed: “Volunteers will be employed on fighting duties only, and Commanding Officers should be assured that these duties will require only the best type of officers and men … They should be young and must be absolutely fit. They should be able to swim and be immune from sea sickness … (b) Officers: Personality, tactical ability and imagination … The officers selected as Commando leaders should be capable of planning and personal leading operations carried out by parties chosen from their own commandos. These officers should be selected entirely for their operational abilities.”

On June 12th, 1940, General Sir Alan Bourne is appointed as Commander, Offensive Operations. By that time MO9 headed by Colonel Dudley Clarke already starts preparing assaults on the French coast. However, after two unsuccessful raids Churchill is most unsatisfied with the results off the raiding campaign. On July 17th, 1940, he issues a directive describing the outline of irregular warfare against the Axis. As a result, the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.), which Churchill calls, The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, and the Directorate of Combined

Operations are raised. He appoints Admiral Sir Roger Keyes as the head of Combined Operations. Keyes Becomes responsible for the direction of all raiding operations and their co-ordination with naval and air forces.

In the mean while the formation of the Commando units has continued alongside these events. On June 28th, 1940, the freshly promoted Lieutenant-Colonel John Frederick Durnford-Slater is given orders to begin raising No. 3 Commando and recruit members. With this, Lieutenant-Colonel Durnford-Slater is the first British commando and No. 3 Commando is the first commando unit of the war. At that moment, No.1 Commando and No. 2 Commando are not raised yet since the intention is to raise them as airborne units. From June 29th, 1940, on the calling for volunteers for special service of a hazardous nature start. The men who respond come from two sources, the units of Home Commands and from the Independent Companies formed as early as April 1940 from volunteers of the Territorial Divisions. Five of these Independent Companies have already seen action on a disastrous expedition to Norway.

A total of ten Commando Units are raised, each with ten 50-man troops. By the autumn of 1940, the Independent Companies, and volunteers form the other Commando Units. In November 1940, all Commandos, now named Special Serice Companies are merged into the Special Service Brigade under command of Brigadier Joseph Charles Haydon. The brigade consists of five Special Service Battalions, each with two Special Service Companies. Primarily this organisation structure is a defensive structure to counter an eventual invasion of the Germans or even conduct Partisan activities when necessary. Once the Battle of Britain is won the Special Service Companies are reformed to Commandos again. Within the individual commandos there is a great resistance against Special Service Brigade and Special Service Battalions. Mainly because of the SS designation. The commanding officer of No. 3 Commando, the first commando Lieutenant-Colonel Durnford-Slater refuses to recognise the existence of the Special Service structure and solely uses the word Commando.

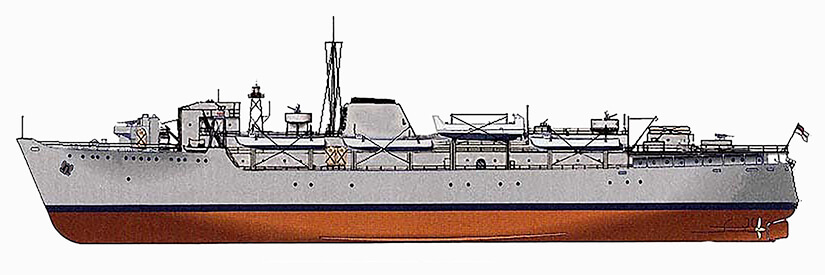

The great resistance against the Special Service Battalions caused, Brigadier Charles Haydon, on February 1st, 1941 to recommend a reversion to the original idea of small Commandos. Several practical reasons also influence this decision. The large Special Service battalions prove extremely difficult to command, control and administer. The size of the Special Service battalions and their subunits has tactical and operational implications for raiding. The battalions did not match the capacity of the small number of available assault ships. Neither the converted merchant ships, the Glen-type, H.M.S. Glenearn, H.M.S. Glenroy, and H.M.S. Glengyle, Landing Ships Infantry (Large), nor the Dutch type, converted passenger steamers, H.M.S. Beatrix, H.M.S. Prince Albert and H.M.S. Princess Emma, Landing Ships Infantry (Medium) could carry a complete battalion or Commando at one time.

Therefore, each Special Service Battalion is subdivided into smaller groups to fit aboard ship, thereby severely complicating command, and control of the unit. It is also impossible to fit a single company, into an Armoured Landing Craft (ALC). And finally, the size of a Special Service battalion meant it would be highly unlikely a complete unit would ever be employed on a single task.

With that in mind the 1941 reorganisation and expansion of the Special Service Brigade is reorganised again in February 1941, with a new organisation and designation being adopted. Various changes are also made in the organisation of the individual Commandos with a view to making them easier to command and control and more suited to available landing ships and craft. The individual Commandos are reorganised, in accordance with the new war establishment issued in February 1941.

Two complete Commandos would now fit aboard a Glen-type Landing Ship Infantry (Large) and a single Commando into each of the Dutch type, Landing Ship Infantry (Medium). A troop would fit into two Assault Landing Craft, leaving space free for five additional attached personnel. This reduction also makes them far easier to command and control during operations. A reduction in the strength of each Commando had another unintended benefit, it provided a painless way of ridding units of unwanted men. No changes are made in the amount of supporting weapons allocated to each Commando. The transport allocated to each Commando also remains on just an administrative basis and training purpose.

During this period in February 1941, a force of commandos under Colonel Robert Laycock is sent to the Middle East to carry out raids in the eastern Mediterranean. This force becomes known as Layforce after their commander. Layforce consists of A Troop from No. 3 Commando, No. 7 Commando, No. 8 Commando and No. 11 Commando. Additional personnel is drawn from No. 50 Commando and No. 52 Commando, two commandos that are raised in the Middle East. The unit arrives in Egypt in March.

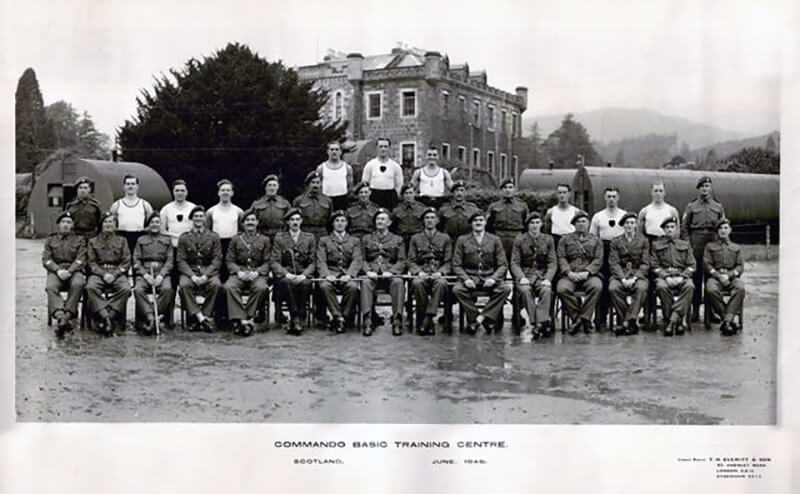

In February 1942, a new Commando Depot opens at Achnacarry in West Scotland under Brigadier Charles Haydon Here all Commando volunteers, sub-units and new units are undergoing a period of intensive Commando training before joining an operation unit or formation. The centralisation of Commando training abandons the doctrine that each Commanding Officer of each Commando is primarily responsible for training his ranks. While an effective system, it also caused a variation in the standards of training and instruction between units and the centralisation of teaching the latest experience during combat operations. The intention is to meet the demands for completely new units and the constant demands for replacements to fill gaps in existing Commandos. The Depot is later renamed to the Commando Basic Training Centre.

From February 1942 the Royal Marines Commandos are raised, enlarging the strength of the Special Service Brigade. Later that year other specialised Commandos are added to the Special Service Brigade. In March 1942 No. 62 Commando in raised, also known as the Small Scale Rading Force. In July No.10 (Inter-Allied) Commando is raised, followed by No. 30 Commando in September 1942 and No. 14 (Arctic) Commando in October 1942.

While small-scale raiding is still going on, Commandos are more and more used to spearhead large-scale amphibious operations in advance of regular units. Examples are Madagascar and Dieppe. During these operations they fight with complete commandos and are tasked with neutralising enemy coastal batteries and seizing preliminary objectives, after which they are quickly withdrawn following the raids. During the initial landings in North Africa two units (No. 1 Commando and No. 6 Commando) are employed in a traditional manner, seizing forts and coastal batteries. However, due to a chronic shortage of troops, No. 1 Commando and No. 6 Commando are retained in the fighting line alongside regular battalions for over five months, in a conventional role.

This conventional role shows the limitations of the Commandos in terms of combat effectiveness and administration. The lack of supporting weapons, vehicles, administrative personnel, and appropriate training limits their prolonged employment. The lightly equipped Commandos prove incapable of carrying out conventional warfare with the weapons at their disposal. Their reliance and training on surprise, speed, darkness, and precise planning to overcome enemy resistance is insufficient on a conventional field of battle. On the administrative side the Commandos only have personnel to their disposal to despatch the force from the port of embarkation and receive them on their return. To provide the necessary support men are withdrawn from the firing line and used as administrative personnel. Besides that, a high casualty rate is suffered during heavy fighting, stretching the existing replacement organisation even more. Due to insufficient drafts of trained manpower received during the campaign, the Commandos have to reorganise with the reduced number of troops available. At the beginning of April, they are forced to withdraw. Even before the decisive battles in Tunisia take place.

The experience gained in North Africa and the intention of employing Commandos during the invasions of Sicily and later Italy, convince senior officers at the Special Service Brigade’s HQ that major changes are needed, in both the organisation and the individual Commandos. In April 1943, a major reorganisation is started by Brigadier Robert Laycock, Operational Commander of the Special Service.

A Special Service Brigade Advanced Headquarters is formed on April 12th, 1943, at Prestwick. This Headquarters has with No. 2 Commando, No. 3 Commando, No. 40 (RM) Commando and No. 41 (RM) Commando under command. During the planning for Husky and Avalanche it works in close cooperation with the senior Headquarters responsible for the planning and conduct of operations involving Commando units, making them aware of the strengths, capabilities and limitations of its units and ensuring they were allocated appropriate tasks. A Rear Headquarters remained in Greta Britain at Sherborne in Dorset, meanwhile, with responsibility for the remaining Commandos, No. 30 Commando, No. 62 Commando, No. 2 SBS, the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties and the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Unit.

Laycock is convinced that in the years to come Commandos will primarily participate in larger-scale operations overseas, mount large-scale raids as well as small-scale raids, and fight alongside regular Army formations in a conventional role. In a detailed paper submitted to Lord Mountbatten, entitled “Role of the Special Service Brigade and Desirability of Reorganization”, he carefully analyses the existing Commando organisation and its future employments envisioned by him. Laycock concludes that there are three future options for the Commandos:

- Disband the complete organisation.

- Adjust the current organisation for sole small-scale raiding.

- Reorganise the organisation to enable them to operate independently as well as in cooperation with conventional forces.

The first option of disbandment of the complete organisation is not taken seriously given the accomplishments of the unit.

The second option of scaling back the Special Service Brigade and simply retaining the Commandos solely for small-scale raiding operations is considered not an option since a wide range of smaller special forces, such as No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando, No. 12 Commando, No. 14 Commando and the Small Scale Raiding Force, had largely taken over the small-scale raiding role. There is no need for a larger organisation anymore to do the same thing exclusively.

So, the third option is decided to be the only way to prepare the Special Service Brigade and their individual Commandos for their future tasks. This involves major changes in the command structure of the Brigade and changes in the order of battle of the brigade and of individual Commando units, intended to fit it for use in both the assault phase of an operation and then the consequent extended fighting during the follow up.

The primary aim is to increase both the firepower, the mobility, and the administrative facilities of each unit to enable them to carry out their original role and fight

alongside regular units for protracted periods of time, although not at the expense of tactical flexibility. Each Commando receives a Heavey Weapons troop, with a mortar and a machine gun section. Headquarters and the individual troops also receive extra light machine guns and mortars for more fire support. Each Commando unit is provided with sufficient transport and administrative personnel to make it mobile and self-sufficient for at least at least a short time. Giving each Commando also a limited mobile reconnaissance capability.

A new Operational Holding Commando, based at Wrexham, was formed to build up a reserve of trained men until a draft was urgently required to restore to full strength a unit heavily engaged in combat.

Laycock had also proposed a Special Forces Group with three brigades with each three Commandos attached to them. The Special Service Group Headquarters would have all the other specialised units attached to it. Halfway 1943 it becomes clear that the reorganisations Laycock proposed are not going far enough to for fill the needs for the future.

In August 1943 a new Royal Marine Engineer Commando company is raised at Dorchester to make the Special Service group more self-sufficient. It is expanded to form a complete Commando of three troops. The unit is first attached to headquarters but later by June 1944 every brigade has a part attached to them except for the No. 2 Special Service Brigade (Mediterranean).

By that time a new Special Service Group, commanded by Major General Robert Sturges is already formed in October 1943. It is tasked with coordinating the various Commando forces following the decision to increase the size of the Commandos by reorganising and retraining complete units from the redundant Royal Marine Division and Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisations (MNBDOs) into new Royal Marine Commandos. A total of six new units Nos. 42-47 (Royal Marines) Commandos are formed with effect from August 1st, 1943, on and trained at the Commando Depot at Achnacarry. With the manpower demands of Operation Overlord No. 48 (Royal Marine) Commando is raised and joins the Special Service Group in June 1944.

With this extra Commando, the Special Service Group is able to raise four Special Service Brigades, each with four commandos and supporting units. Two brigades, the 1st and 4th remain in North-West Europe for service, while the 2nd serves in the Mediterranean. The 3rd Brigade’s operational area is South-East Asia Command.

The functions of the new Special Service Group Headquarters are administrative, dealing with pay, organisation, and the training of its formations and, to a far lesser extent, planning. It is not designed to work in the field, although individual members of its staff help

its subordinate formations with planning of operations. Even so, a detached tactical Headquarters of the Special Service Group, commanded by Brig John Durnford-Slater, was attached to the HQ of 2nd British Army, to ensure Commando interests were safeguarded during the D-Day landings. Each Special Service Brigade Headquarters, with its own attached Signal Platoon, was an operational Headquarters and commanded and administered four Commandos in the field.

By June 1944 the Special Boat Unit or No. 2 Special Boat section is disbanded and No. 48 (Royal Marine) Commando has taken the place in the No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando in the No. 4 Special Service Brigade. The troops of that commando are attached to every individual Brigade for liaisons duties.

The result of the 1943 reorganisation and re-equipment is that the Commandos increasingly employ more conventional tactics, primarily acting as assault or light infantry. In the years to follow they move more and more towards conventional warfare where surprise or darkness no longer form the basis for a plan of attack to cover the approach and withdrawal from an objective. They still do employ highly aggressive light infantry fighting tactics, in which fire, manoeuvre and battle drills play a key role, during both the initial (amphibious) assault and ensuing conventional operations ashore pitted against regular, alerted enemy troops.

By the end of the war their initial role of small scale raiding is completely abandoned and left to forces as the Special Air Service, the Special Boat Squadron. However, some small-scale raiding operations continue, most of them along the eastern seaboard of the Adriatic, where elements of No. 2 Commando Brigade fight alongside Yugoslav partisans on offshore islands and along the coast.

With the war in Europe coming to an end, a new Commando (Light) organisation is agreed upon for Commando units operating in the war against Japan. It involves the addition of further 3 inch mortars to each the heavy weapons troop and far greater administrative personnel, given the distances between bases and operational areas in theatre. The sudden end of the war with the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki causes these changes not to be implemented.

At the end of the Second World War, all the British except for some Royal Marines Commandos are disbanded. This left only three Royal Marines Commandos and one brigade with their supporting Army elements.