| Page Created |

| February 4th, 2023 |

| Last Updated |

| January 26th, 2024 |

| Related Pages |

| British Biographies Special Air Service Biographies Special Air Service |

| Robert Blair “Paddy” Mayne |

|

| Royal Artillery |

|

| Royal Ulster Rifles |

|

| Army Commandos |

|

| Special Air Service |

|

| Biography |

Robert Blair “Paddy” Mayne was a British Army officer who served in the Special Air Service during World War II. He is a legendary figure in the SAS and considered as one of the most successful and innovative special forces commanders of the war.

Paddy Mayne is born on January 28th, 1915, in Newtownards, County Down, Northern Ireland. He is the youngest of seven children and grows up in a military family. His father is a veteran of the Boer War and his brothers also serve in the British Army. From an early age, Mayne shows exceptional athletic ability. He develops a strong love of the outdoors. He becomes an enthusiastic sportsman. During his teenage years, he shows talent in rugby, golf, cricket, and marksmanship. His physical strength and coordination stand out among his peers.

By his mid-teens, he plays as a forward for his school rugby team. He also represents the local Ards Rugby Football Club. His performances indicate the early development of his rugby abilities. Coaches and teammates recognise his determination and resilience.

Those who know him in youth describe a complex character. He is quiet and bookish at times. He also possesses a bold and adventurous streak. This contrast becomes a defining feature of his personality. These traits later contribute to his formidable reputation.

Robert Blair Mayne attends Regent House Grammar School in Newtownards. He excels academically and athletically throughout his school years. He stands approximately 1.91 metres tall. He weighs about 98 kilograms in his prime. He already cuts an imposing figure as a young man.

Blair begins playing rugby at Regent House Grammar School, Newtownards. At eighteen, he becomes captain of Ards RFC. He excels in multiple sports. Standing 1.89 metres tall, with powerful hands, he knocks out his first boxing sparring partner. In August 1936, he becomes Irish Universities Heavyweight Champion. He later reaches the final of the British Universities Championship and loses on points. His performances demonstrate discipline, control, and technical skill.

He also distinguishes himself in cricket and golf. His achievements are not confined to sport. He earns a reputation as a diligent and capable student. This combination of intellect and physical presence secures his admission to Queen’s University Belfast. He enrols to study law.

| University |

In 1937, he joins the Queen’s University rugby team while studying law. At Queen’s University Belfast, Mayne continues to flourish. He balances demanding legal studies with intensive sporting commitments.

He remains active in rugby during his university years. He plays for Queen’s University and for Malone Rugby Football Club in Belfast. He also competes regularly in golf. Around this period, he wins his club President’s Cup.

Robert Blair Mayne enjoys a remarkable rugby career before war intervenes. He plays as a powerful second-row forward. His physical presence and work rate define his style. He emerges on the Irish rugby scene in the late 1930’s.

In February 1937, he earns his first cap for Ireland national rugby union team. The match takes place against Wales in the Home Nations Championship. Ireland secures a narrow victory. Mayne’s impact is immediate. Over the next two years, he becomes a regular selection. By 1938, he accumulates six international caps.

He is known for strength and aggressive play. He also shows unexpected mobility. In 1938, Ireland faces England at Lansdowne Road. The match ends in a heavy 14–36 defeat. Mayne scores a try from a line-out. His charge over the line stands out. Contemporary reporters praise his quiet efficiency. They note his speed across the ground for a man of his build. His play repeatedly disrupts opposing backlines.

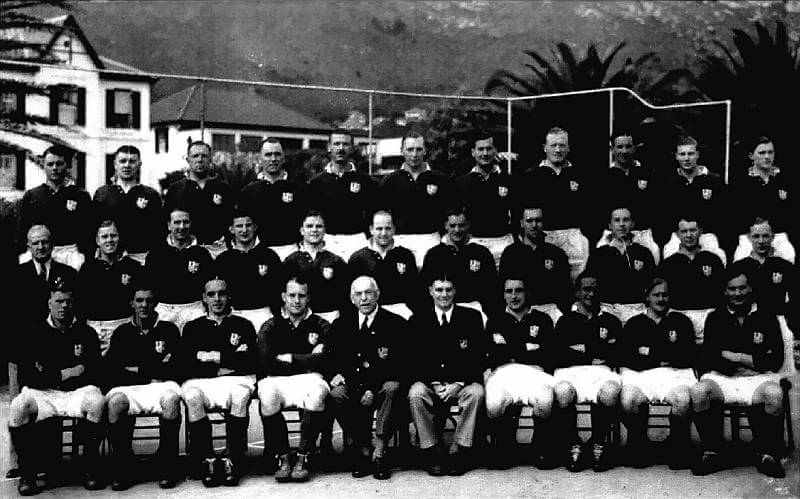

In 1938, Mayne receives one of rugby’s highest honours. He is selected for the British Isles rugby team tour to South Africa. He is twenty-three years old. Since 1888, twenty-four Queen’s alumni represent the Lions. Blair is selected after only three international caps. Injuries prevent Welsh stars Cliff Jones and Wilf Wooller from from touring. The tour includes seventeen matches. Mayne plays in seventeen of the fixtures. He appears in all three Test matches against the Springboks. The series is lost. His performances earn admiration. South African newspapers praise his resilience within the pack. They describe the forwards as standing gamely against immense pressure.

Earlier in the tour, Team Captain Sam Walker is knocked unconscious by a tackle. As he regains awareness, stretcher-bearers run past him to tend to Blair. Later, Blair kneels beside Walker and says the matter is settled.

Away from the pitch, his behaviour attracts attention. His actions during the tour become rugby folklore. He damages hotel furniture after heavy celebrations. He fights with sailors on the docks.

He also frees a convict labourer he befriends at Ellis Park Stadium. In Johannesburg, prisoners build stands at Ellis Park. They are chained at night. After drinking, Blair releases one known as Rooster. Blair lends him his jacket. A ticket bearing Blair’s name remains inside. When Rooster is recaptured, Blair is identified and briefly goes absent without leave.

Two other episodes during the 1938 British Isles tour of South Africa explain why Robert Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne stands apart from all others to represent the Lions. Both occur within weeks of each other and reveal sharply contrasting sides of his character.

The first takes place midway through the tour at a hotel in Pietermaritzburg. The management of the British Isles Touring Team becomes exasperated by the off-field behaviour of their first-choice lock. They decide that Blair should share a room with his Irish teammate and fly-half George Cromey. Both men previously play together at Queen’s University, Belfast. The pairing is not social. Cromey is ordained as a Presbyterian minister during the tour. The management hopes he will restrain Blair’s excesses. The plan fails.

When not playing or travelling, the team attends receptions and dinners hosted by South African dignitaries. During one such period, winger Jimmy Unwin remarks casually that the team has not eaten enough fresh meat. Blair takes the comment literally.

Accounts differ over what follows, but Cromey’s diary provides a firm reference. During a formal dinner, Blair goes to the hotel bar and meets two Afrikaners carrying rifles. They invite him lamping, which involves driving into the bush, shining a light, and firing at reflected eyes. Blair joins them while still dressed in black tie.

Unknown to the Afrikaners, Blair is an experienced hunter. He kills a springbok with his first shot. He loads the animal and returns to the hotel sometime during the night or early morning. At approximately 09:00, he enters the shared room carrying the carcass.

Blair drags the springbok along the hotel corridor. He breaks into Unwin’s room and throws it onto the bed. One horn cuts Unwin’s leg. Blair then hangs the animal outside the South African coach’s door. A note reads, “A gift of fresh meat from the British Isles touring team.”

The incident reinforces Blair’s reputation as a reckless figure. Team manager Major Hartley considers sending Blair home after the antelope incident. Team Captain Sam Walker intervenes, arguing Blair’s value. The decision proves decisive.Three weeks later, events on the field reshape that image.

The third Test against South Africa takes place at Newlands, Cape Town. The hosts win the first Test 26–12 at Ellis Park, Johannesburg. The second Test follows in Port Elizabeth under extreme heat. The match becomes known as the Tropical Test. South Africa wins 19–3. By the third Test, the tourists are exhausted after more than two months on tour. Eight players are unavailable through injury. Despite this, the team refuses to abandon its attacking style.

At half-time, South Africa leads 13–3. A series whitewash appears inevitable. Springbok captain Danie Craven exploits the wind in the first half. A groundsman tells him it will drop after the interval. The wind instead strengthens.

In the second half, Blair is joined in the second row by captain Sam Walker, normally a prop. The two Irish forwards drive a sustained revival. The comeback includes a disputed drop goal. The ball’s passage between the posts remains uncertain. South Africa does not protest.

Late in the match, South Africa believes winger Dai Williams has scored. The referee disallows the try for a forward pass. The match ends 21–16. It is the highest score ever recorded by a Lions side at that point. It is only the third South African defeat at Newlands in forty-seven years. It is also the final occasion on which the Lions play in blue.

The result is so unexpected that a London news agency assumes the score is a misprint. Walker later writes that the true reward of touring lies not in moments of play but in mutual respect within the team. He tells the Cape Argus that the match will be remembered as one of the most exciting ever played in the country.

Blair later receives a letter from a South African admirer praising his speed, agility, and strength. The writer adds a polite request that Blair might smile next time.

After returning from South Africa, Mayne continues with Ireland in the 1939 season. Ireland defeats England 5–0 at Twickenham. Scotland is also beaten. Hopes rise for a Triple Crown. In March 1939, Ireland faces Wales in Belfast. The deciding match is hard fought. Ireland loses 0–7. The championship slips away.

This match proves to be Mayne’s final international appearance. Later in 1939, the Second World War begins. His sporting career ends abruptly. He finishes with six caps for Ireland. He also plays three Test matches for the Lions. His achievements as a fierce lock forward later stand in the shadow of his wartime fame.

In early 1939, he also graduates with an LL.B., Bachelor of Laws. He qualifies as a solicitor. He briefly works at a Belfast law firm. Europe stands on the edge of war. His formal legal training soon contrasts sharply with the military career he is about to begin.

| Multimedia |

| World War 2 |

Before the start of World War II in 1939, Mayne joins the Supplementary Reserve and receives a commission in the Royal Artillery. By that time, he sets aside his legal career. In early 1939, he receives a commission in the Royal Artillery. He is posted to the 5th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, later 8th (Belfast) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment. He was transferred to the 66th Light AA Regiment. In 1940, aged twenty-four, he transfers to the 4th Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles, a reserve unit.

He soon becomes restless. He seeks active service. He volunteers for No. 11 (Scottish) Commando. This unit is newly formed for raiding operations. The transfer sends him to the Middle East. In June 1941, his unit takes part in the Allied invasion of Vichy-controlled Syria and Lebanon.

On June 9th, 1941, during the Battle of the Litani River, Lieutenant Mayne leads his section in combat. He captures all assigned objectives. He takes numerous French prisoners. The river crossing is hard fought. His leadership and courage stand out in his first engagement. He receives a Mention in Despatches for gallantry.

Soon after Litani, his career takes a decisive turn. Regimental accounts describe an altercation with a superior officer. Some versions claim he strikes his commanding officer in frustration. Later accounts place him under arrest and awaiting court-martial. While confined, he attracts the attention of Major David Stirling. Stirling is forming a new special forces unit in mid-1941.

By late 1941, Mayne joins Captain David Stirling’s unit. Mayne is recommended to Stirling by his friend Lieutenant Eoin McGonigal, an officer of No. 11 (Scottish) Commando and early Special Air Service volunteer. It is known as L Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade. The unit assembles in the North African desert. Its task is deep raiding behind Axis lines. Stirling recognises Mayne’s strength, intelligence, and leadership.

Early operations test the new unit. A parachute raid in November 1941 ends in failure. Morale suffers. On the night of December 14th, 1941, Mayne restores confidence. He leads a small team against the enemy airfield at Wadi Tamet in Libya.

His men infiltrate the airfield on foot. They storm the Italian officers’ mess. Enemy aircrew are killed or dispersed. Mayne’s party sabotages aircraft using Lewes bombs. They destroy at least fourteen aircraft by explosives. Others are wrecked by machine-gun fire. Fuel dumps, an ammunition store, and communications are destroyed.

In total, twenty-four German and Italian aircraft are eliminated. During the raid, Mayne tears the directional gyro from an Italian bomber by hand. This act enters Special Air Service legend. The raid proves the effectiveness of small raiding teams. In early 1942, Mayne receives the Distinguished Service Order. He is promoted to captain. A second Mention in Despatches follows.

Throughout 1941 and 1942, Mayne conducts continuous desert operations. The Special Air Service attacks airfields, supply columns, and communications across Libya and Egypt. On July 26th, 1942, he takes part in the raid on Sidi Haneish airfield in Egypt. Special Air Service jeeps storm the runway at night. Machine-gun fire destroys up to forty aircraft. Losses are minimal.

By the end of the desert campaign, Mayne is credited with destroying over one hundred enemy aircraft on the ground. His name becomes feared behind Axis lines.

In January 1943, Major David Stirling is captured. Command of 1st SAS Regiment passes to Major Mayne. He restructures the unit. It divides into the Special Raiding Squadron and the Special Boat Section. Mayne becomes commander of the Special Raiding Squadron.

In July 1943, the SAS deploys to Sicily. Operations shift to direct assault. On July 10th, 1943, Mayne leads an amphibious landing at Capo Murro di Porco. His men climb cliffs under fire. They silence an Italian coastal battery. Days later, he leads a daylight attack on Augusta harbour. Defences collapse under surprise assault. Hundreds of prisoners and large stores are captured.

His actions secure the flank of XIII Corps. His leadership earns high praise. He receives a Bar to the DSO. The citation highlights his courage, determination, and personal example.

By late 1943, the unit resumes the title 1st Special Air Service Regiment. Mayne is promoted lieutenant-colonel. In 1944, the regiment deploys to Western Europe. Operations support the Normandy invasion and its aftermath.

From mid-1944, Special Air Service detachments operate across France and the Low Countries. They support the Maquis. They sabotage railways and ambush convoys. Mayne frequently enters the field himself. In August 1944, he parachutes into Burgundy during Operation Houndsworth. He rallies scattered units. He drives through the front lines to link with advancing American forces.

For operations in France and Belgium, he receives a second Bar to the DSO. The citation credits his leadership and disregard for danger.

In April 1945, the Special Air Service advances into Germany. On April 9th, 1945, near Oldenburg, two Special Air Service squadrons are ambushed by German Fallschirmjäger. The leading jeep is destroyed. Its commander is killed. Others are pinned down.

Lieutenant-Colonel Mayne intervenes immediately. He mounts a Bren gun on his jeep. Lieutenant John Scott volunteers as gunner. Mayne drives repeatedly into the ambush zone. He directs fire at close range. His actions draw enemy fire. Other Special Air Service troops manoeuvre against the Germans.

Mayne stops to rescue wounded men under fire. The ambush collapses. German forces are killed, wounded, or driven off. His action saves lives and breaks the enemy position.

A citation for a Victoria Cross is issued by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, praising Mayne’s “cool and calculated bravery” and recognising his “single act of bravery” which broke the enemy defenses. Despite this, the recommendation for a Victoria Cross was downgraded to a fourth award of the DSO.

Senior officers express dismay. Major-General Sir Robert Laycock writes in support. King George VI privately questions the decision. David Stirling later condemns the outcome. Despite this, Mayne finishes the war with four DSO’s.

In 1945, France awards him the Légion d’honneur and the Croix de guerre. By war’s end, Paddy Mayne stands as one of Britain’s most decorated officers. His reputation rests on fearless leadership and relentless offensive spirit. The Special Air Service war diary, containing photographs, orders, and maps, is entrusted to him after the war.

| Multimedia |

| Post-War |

Robert Blair Mayne faces major adjustment when the war ends in 1945. The Special Air Service is disbanded in October 1945. He is thirty years old. The structure and intensity of military life disappear abruptly.

He searches for new purpose. In 1945, Paddy Mayne is selected to join the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey as the deputy to the expedition leader, Edward W. Bingham. The expedition conducts scientific survey work. Its base lies in the Falkland Islands. Planned operations include Deception Island and Port Lockroy in the Antarctic region.

His wartime injuries soon intervene. He suffers chronic and severe back pain. The condition results from repeated parachute landings and combat strain. In early 1946, he withdraws from the expedition. Persistent pain forces his return. This marks the beginning of a difficult post-war period.

Mayne goes back to Newtownards where he worked as a solicitor and later serves as the Secretary to the Law Society of Northern Ireland. He joins a solicitor’s practice in Newtownards. He works steadily and reliably. Within several years, he becomes Secretary of the Law Society of Northern Ireland. The position carries significant professional standing.

Outwardly, he appears settled. The former commander now lives as a country solicitor. Privately, the transition proves difficult. The loss of military camaraderie weighs heavily. He suffers from severe back pain which restricted him from participating in activities such as rugby, even as a spectator.

Friends and family note a gradual withdrawal. He becomes increasingly reserved. He spends more time reading. Literature has always held his interest. Social life becomes limited. Physical pain remains constant.

Psychological strain also persists. Modern assessment would likely identify post-traumatic stress disorder. The condition is compounded by abrupt separation from wartime identity. Like many veterans of his generation, he receives no formal mental health support.

At times, he turns to alcohol. Periods of heavy drinking occur. Those close to him understand the cause. They view it as the delayed effect of prolonged combat. Earlier wartime incidents are later reinterpreted in this light. His behaviour reflects grief, strain, and unprocessed loss.

In civilian life, Mayne avoids publicity. He rarely speaks about the war. He does not seek recognition. He attempts to live quietly in his home town. His adjustment remains marked by pain, restraint, and silence.

| Dead and Legacy |

Tragically, Mayne passes away on the night of December 13th, 1955, at the age of forty. During the evening, he attends a regular meeting of his Masonic lodge. He is a member of the Freemasons. After the meeting, he drinks with a friend in the nearby town of Bangor. He later drives home alone.

At around 04:00, less than 460 metres from home, he collides with a parked farm vehicle. The road is dark. He is driving his red Riley roadster. The impact is severe. He breaks his neck and is found dead at the scene. His car is badly crushed.

Mayne is buried two days later. He is remembered by the many mourners who attend his funeral and pay their respects. He is buried in the family plot in the Movilla Abbey graveyard in Newtownards. His masonic jewel is kept by an old schoolfriend for many years before being donated to the Newtownards Borough Council where it is displayed in the Mayoral Chamber. In honor of Mayne’s legacy, a road in Newtownards is named after him, and a statue is dedicated to him outside the town hall in 1997.

News of his death shocks the local community. It also affects former comrades across Britain and Ireland. His funeral takes place in Newtownards with full honours. Hundreds attend. He is buried in the family plot at Old Movilla Abbey Churchyard. Military officers, civic leaders, rugby teammates, and local residents are present.

In the years after his death, his reputation continues to grow. In Newtownards, his memory is publicly honoured. A main road is renamed Blair Mayne Road. In 1997, a bronze statue is unveiled outside Newtownards Town Hall. It depicts him in combat uniform.

Within the British Army, he is remembered as a founding figure of the Special Air Service. His wartime actions become central to Special Air Service tradition. His exploits appear in books and biographies. He also inspires fictional characters in war literature.

In popular culture, his story reaches new audiences. In 2022, he is portrayed by Jack O’Connell in the television series SAS: Rogue Heroes. The portrayal renews interest in his life. Military historians often cite him as an example of the soldier-athlete. They highlight his physical courage, tactical instinct, and independence of mind.

Debate continues over the Victoria Cross denied to him in 1945. Many regard the decision as unjust. In 2005, more than one hundred Members of Parliament sign motions supporting a posthumous award. The government refuses to change policy. No VC is granted. Further calls for recognition continue into the 2020’s.

Paddy Mayne is remembered as one of the greatest and most innovative special forces commanders of World War II. His bold and daring tactics, his physical strength and athleticism, and his ability to inspire his men made him a legendary figure in the Special Air Service. He was a pioneer of special forces operations and his legacy continues to influence the tactics and techniques used by special forces units around the world today.

| Sources |

Great Article. Thank you for this information.