| Page Created |

| August 24th, 2025 |

| Last Updated |

| October 9th, 2025 |

| Canada |

|

| Great Britain |

|

| The United States |

|

| Facilities |

| British Facilities Canadian Facilities U.S. Facilities |

| Related Pages |

| DUKW Landing Craft, Assault Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel U.S. Assault Teams Assault Training Center, Devon, Great Britain |

| Slapton Sands |

| Military training in Great Britain |

Military training in Britain traditionally takes place on land owned by the War Office or Ministry of Defence. These areas are usually remote and sparsely populated. With the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939, Britain faces the urgent need to train thousands of troops. This requires additional land for training facilities.

The demand for training land competes with the need for food production. The nation must be as self-sufficient as possible. Officials therefore try to use unproductive land with low populations for training purposes. The agreement is that land will be returned once the war ends.

Existing ranges and camps are expanded. New training areas appear on moorland, downland, heath and in woods. Chalk pits and quarries serve as rifle ranges. Beaches are used for firing weapons out to sea. These locations work for land warfare training. Yet by 1943 there is little provision for large-scale beach assault practice.

The decision to invade occupied Europe is confirmed at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill agree to launch Operation Overlord. Stalin is invited but cannot attend due to Soviet offensives.

The invasion requires large areas of coastline for realistic training. Most southern and eastern beaches in Britain are fortified with mines and anti-invasion defences. Many coastal areas are also RAF bombing and gunnery ranges. Suitable beaches are scarce.

Operation Overlord demands the formation and training of five Naval Assault Forces. Each must be capable of landing a division at assault scale. Assault Commandos also require lift. Training must include the use of live ammunition to support the landings. Naval gunfire, bombing, and landing craft support all need to be rehearsed.

Flotillas of landing craft must synchronise landings with air support. All three services require combined training. The Admiralty assumes responsibility for finding suitable sites, working with the War Office, Air Ministry, and Combined Services.

| Multimedia |

| Assault Training Area Selection Committee |

A special committee, the Assault Training Area Selection Committee (ATASC), forms under Captain R. J. L. Phillips, Royal Navy. Its role is to locate and recommend areas for combined assault training. Reconnaissance of proposed sites is carried out immediately.

By mid-1943, only one close support range exists, at the Needles. It has been used since 1942 but is too small and too exposed for large-scale training. The Admiralty therefore defines requirements for new areas.

The plan calls for two areas near Milford Haven, one between Plymouth and Falmouth, one between Dartmouth and Prawle Point, two between Portland and the Needles, one between Yarmouth and Harwich, one between Bridlington and Spurn Point, and two in the Rosyth Command. Each Assault Force needs two areas, to allow for poor weather.

Each area must be suitable for a battalion-scale landing, with the possibility of brigade training under limited conditions. Size, shelter, and proximity to embarkation ports are critical. The landings require shallow approaches, beaches 500 to 1,000 metres long, and inland depth of at least 5,000 metres. Civilian clearance must be possible within twelve hours. Mines must be removed, and seaward approaches swept.

The Assault Training Area Selection Committee meets for the first time at the Admiralty in London on Thursday July 6th, 1943 at 11:30. Captain R. J. L. Phillips, Royal Navy, is in the chair. Senior representatives from the Admiralty, War Office, Air Ministry, and Combined Operations are present. The task is urgent. Operation Overlord is only months away.

The committee agrees its first priority is to establish the basic requirements of a combined assault training area. They discuss the size of beaches, the depth of hinterland, the level of clearance from civilians, and the need for live fire. The committee recognises that amphibious assaults involve all three services. Every element must be rehearsed together under realistic conditions.

They note that existing ranges, such as the Needles on the Isle of Wight, are inadequate. The Needles has been in constant use since 1942 but is far too small for divisional training. Its beaches are also exposed and vulnerable to weather. A new solution is required.

During the meeting, the Admiralty sets out the scale of training demanded. Each Naval Assault Force must have two separate training areas. This will reduce disruption from winter storms. The beaches must be long enough to land at least a battalion, with inland depth for manoeuvre and consolidation. A frontage of 2,500 to 3,000 metres is considered essential. Inland, the area must stretch at least 5,000 metres, and ideally 8,000.

The committee confirms that each training site must include at least one beach suitable at all states of the tide. Easy seaward approaches are vital. Clearance of civilians must be possible within twelve hours to allow for firing practice. This notice period is set deliberately short. Weather forecasts are unreliable. If longer clearance is needed, exercises could be cancelled at the last minute.

The committee also defines that all minefields on beaches must be lifted. Seaward approaches must be swept of enemy mines. Other obstacles may remain for training purposes.

Dates are then set for when each area is required. The first must be ready by October 1943. The Slapton Sands area in South Devon is marked as essential and is listed for use by November 1943. This gives only four months to secure, clear, and prepare it.

On the following day, July 7th, 1943, the committee issues a detailed directive for the use of Slapton. It is allocated to Force O, the American naval and ground force assigned to assault Omaha Beach in Normandy. Force O, when fully assembled, will comprise twelve Landing Ships Tank, thirty major landing craft, and two hundred minor craft.

The directive specifies that these vessels will operate from bases at Falmouth, Plymouth, Fowey, Salcombe, Dartmouth, and Teignmouth. Additional embarkation will take place from hards at Torquay and Brixham. Dartmouth and Salcombe will also serve smaller training units. Slapton will therefore become the primary American training ground for beach assaults in Britain.

The committee’s conclusions are firm. Without large areas like Slapton, proper rehearsal for Overlord is impossible. With the clock ticking, reconnaissance of the South Devon coast is ordered at once.

| South Devon Area |

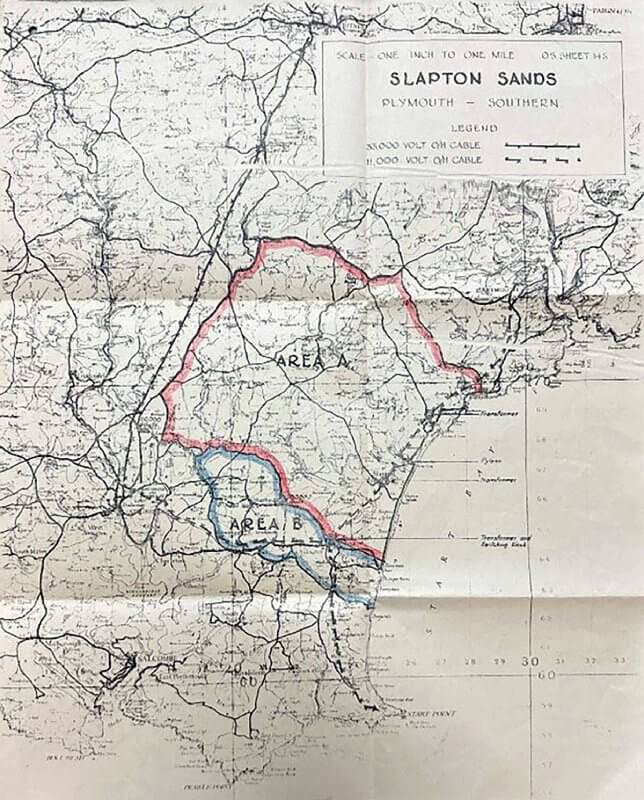

On August 3rd, 1943, Assault Training Area Selection Committee reconnoitres Slapton Sands and nearby beaches. Blackpool, Slapton, Beesands, and Hall Sands are inspected. Slapton offers long stretches but consists mainly of loose shingle with steep gradients. Vehicles will struggle without roadways. Agricultural land is valuable, and over 1,500 civilians would be displaced. Exits from the beaches are limited.

The committee concludes that only limited exercises without live fire or vehicle deployment are possible. Slapton might be used if cleared to a depth of 500 metres for rockets and smoke. Yet the committee considers the area unsuitable unless civilian displacement is enforced.

A second reconnaissance on September 8th, 1943 by Brigadier General Norman Cota and Major Fairburn confirms this. Cota notes that vehicular exits are insufficient and demands manoeuvring rights across public highways. He also warns that covering fire could destroy villages such as Torcross, Stokenham, Chillington, and Sherford, as well as utilities and reservoirs. Restrictions on live firing near civilian areas are advised.

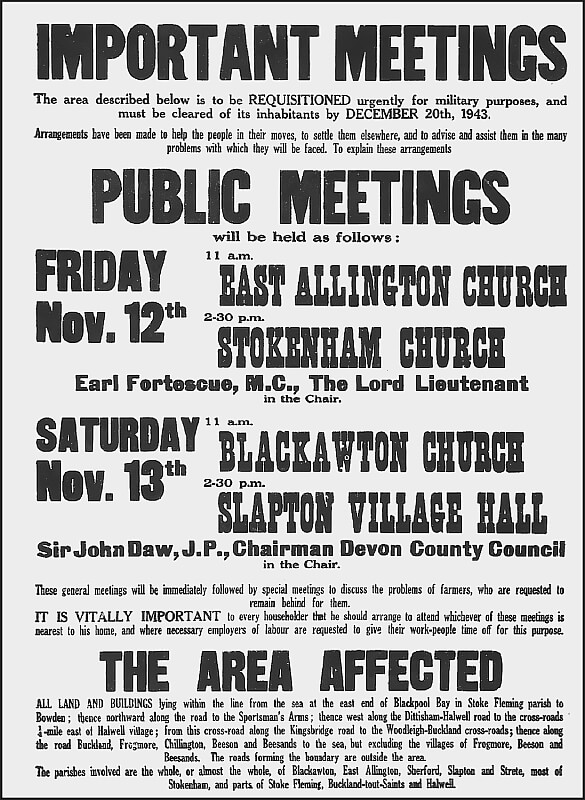

On October 20th, 1943, the review of potential sites in Devon, Wales, and Scotland concludes. Slapton Sands is selected for full live-fire assault training. The area is to be requisitioned under Defence Regulation 51 and completely evacuated by January 1st, 1944.

On November 3rd, 1943, the War Cabinet meets to approve the plan. Present are Clement Attlee, A. V. Alexander, R. S. Hudson, Ernest Brown, Sir James Grigg, and senior military leaders. General Nye stresses that success in France depends on realistic combined training.

Training must replicate naval bombardment, air strikes, and the lifting of fire immediately before landings. Coastal rehearsal is essential. Slapton Sands is the only site that meets requirements.

The Cabinet recognises the serious impact on civilians. Over 2,700 residents must leave, with 1,800 finding their own arrangements. Housing will be provided in Torquay and Paignton. Compensation is limited under existing law, though small funds may be used for hardship cases. Historic buildings are to be spared from damage wherever possible. Farmers are told to find temporary homes, though no return date can be promised.

The Cabinet approves the requisition. Slapton Sands and its villages are cleared. The area is set to play a decisive role in the training for the invasion of Europe.

| Multimedia |

| Conference |

From May 24th, 1943 to June 23rd, 1943, Allied planners hold a major conference at the Assault Training Centre in Woolacombe, North Devon. The aim is to collect and evaluate every available fact about amphibious landings. They study past operations, analyse failures, and review new ideas to shape the coming invasion of Europe.

The Assault Training Centre stands on the exposed North Devon coast, facing the Atlantic and the Bristol Channel. It is commanded by United States Army Colonel Paul W. Thompson. The centre controls and provides facilities for training entire assault divisions under realistic combat conditions. It also experiments with new landing methods and develops tactics and techniques.

The site is ideal. There are 7.3 kilometres of beaches open to the ocean and another 3.6 kilometres along a sheltered estuary. Behind the beaches lies terrain six kilometres deep, used for live firing and manoeuvre. The beaches are flat with moderate surf, stronger than that expected on France’s west coast. To mirror the Atlantic Wall, the Allies fortify these beaches using German methods. They build bunkers, trenches, mortar pits and gun positions. Large-scale assault exercises take place here. Soldiers train with specialist assault weapons, demolitions, and landing craft loading and unloading drills.

The conference brings together senior British and American officers. Their task is to learn how to break through Hitler’s Atlantic Wall and to ensure troops know their mission and terrain before they cross the Channel. Many attendees are veterans of previous amphibious operations. They include Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers, commanding general of United States forces in Europe, and Brigadier General Norman Cota, chief of Combined Operations, European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA). Senior British officers such as Major General J. C. Haydon, Vice Chief of Combined Operations, also play key roles.

Brigadier General Cota sets the tone. He warns that confusion and chaos are inherent in an opposed landing. Careful, honest and simple planning is essential. Infantry must first defeat the sea and weather, then pass through obstacles defended by concentrated fire. Plans must accept that navigation errors, landing confusion and schedule disruption will occur.

The conference examines past operations from both attack and defence perspectives. Dieppe dominates discussion. The failed 1942 raid exposed critical weaknesses. Naval training before Dieppe had been too short. Land, sea and air forces lacked a common doctrine. Command was centralised and overwhelmed. The assault collapsed when tanks failed to breach beach defences. Withdrawal was improvised. Only experienced naval officers prevented total disaster.

Several key lessons emerge. Stronger forces are needed to breach German coastal fortifications. Heavy and sustained air and sea bombardment must soften defences. Early landing waves need massive, well-organised fire support. Plans must remain flexible, with large reserves afloat to exploit success or adapt to changing conditions. Landing craft flotillas must reach a far higher standard of training and organisation than before.

Specialist subjects follow. Presentations cover the support of landings, airborne troops, armoured fighting vehicles, artillery, infantry, signal communications, chemical warfare, supply, administration and medical services. Air and naval aspects of communications and medical support are examined. Combined arms doctrine and field exercises are discussed. Major General Percy Hobart, commander of the British 79th Armoured Division, briefs on specialist assault armour, including amphibious Duplex Drive tanks. Details remain secret at the time. German defence doctrine and the reduction of obstacles receive close attention.

Speakers stress that no modern precedent exists for a cross-Channel invasion against a heavily fortified coast. Napoleon failed to invade Britain. Hitler failed to invade Britain. Both were defeated by distance, weather and the Channel itself. The Allies now face the same obstacles in reverse. The sea is short in distance but long in difficulty.

The English Channel is treacherous and weather unpredictable. Soldiers in landing craft will suffer seasickness. Even when it passes, stamina and combat readiness drop. Continuous supply will be difficult if storms follow the landing. The Allies must secure ports or create sheltered anchorages to land men, vehicles and supplies without pause.

Direct support for the first waves is studied. Air cover must disrupt enemy reinforcements, supplies and morale, but close support is dangerous during the beach assault. Naval fire must be closer and heavier than at Dieppe. The 4-inch guns used there were inadequate; 305-millimetre (12-inch) guns at point-blank range are recommended. Armoured monitors are considered for this task. For the assault craft themselves, 20 mm Oerlikon cannon and .50 calibre heavy machine guns are standard, but heavier two-pounder and 40 mm guns are advised.

Airborne troops are confirmed as vital. They can disrupt enemy reinforcements and seize key terrain inland. Training must focus on squad and platoon leaders. In chaos, junior leaders decide whether the beachhead survives. Training must be long, thorough and demanding. It will expose weak leaders but save lives on D-Day.

The United States adopts the Regimental Combat Team as its assault framework. Each Regimental Combat Team consists of an infantry regiment with organic artillery, anti-aircraft batteries, reconnaissance platoons, signals, medical and ordnance detachments. Engineer battalions and beach groups add specialised support. Beach groups include quartermaster, ammunition, maintenance, military police, amphibian truck, chemical, transport and railhead units. They control landing zones, move supplies inland and keep the beaches clear under fire. Naval beach parties land first to mark ranges, guide boats and manage follow-on waves.

All these support troops train for combat and integrate fully with the assault divisions they will serve.

As the conference closes, a common spirit emerges. Officers of the British and American Army, Navy and Air Forces work together as equals. Uniform and service matter less than the shared goal: the successful invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. This cooperation, born on the training beaches of Devon, will prove vital when the real assault begins.

| The Slapton Sands Training Area |

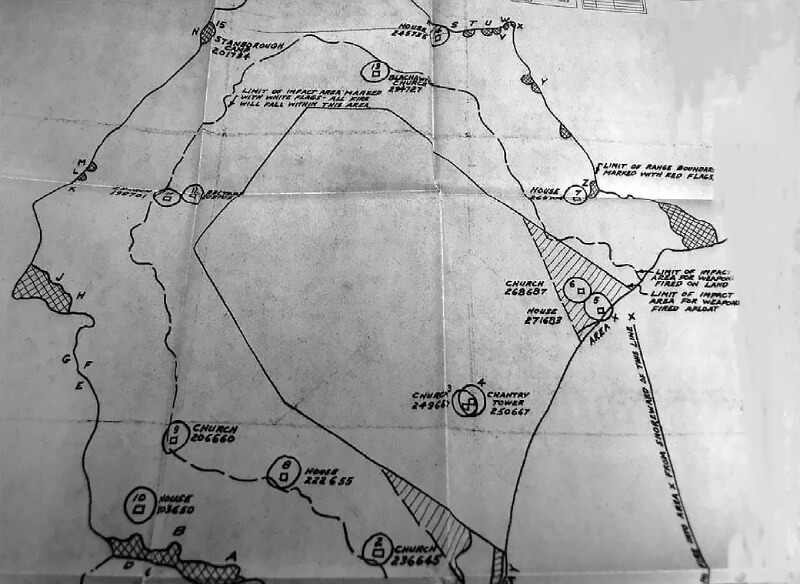

The training area at Slapton Sands is organised like a formal army range. Range Standing Orders govern its use. A dedicated Range Party, commanded by Colonel Martleing from Ash House near Blackawton, manages operations.

The range party secures the area. They place barricades across approach roads, with sentries at key points such as Frogmore and Stoke Fleming. Units opening a road must post guards until the barricade is restored. Civilians are kept out at all times. Sentries are posted and withdrawn as required. Damaged roads or bridges are repaired, and property damage is reported. Before exercises, the party ensures safety and clears the range. Red danger flags mark boundaries. Transit markers define the impact zones for naval gunnery.

Nine single-man patrols cover the 30-kilometres perimeter. The team repairs permanent targets, maintains roads and property, and extinguishes small fires if no unit is present. They salvage metal and cook for the sentries and staff. The party also provides local communication and safety control during live fire.

Strict firing safety rules apply. Anti-tank guns and armour-piercing ammunition are banned. Solid shot practice rounds are also prohibited. Naval gunnery has defined impact areas about 2.7 kilometres inside the range boundary. No fire is allowed outside these limits. Foreshore zones can be used for direct fire from the sea, but gunnery angles must prevent stray ricochets.

Bombing and strafing by aircraft follow strict limits. Bombs heavier than 272 kilograms are banned. Pyrotechnic signals allow instant ceasefire if needed. Shore firing control parties from United States Navy or Royal Navy units supervise live shoots. They confirm range clearance with the commandant, give ceasefire orders if danger arises, and report fall of shot.

Unexploded ordnance is a constant hazard. After each exercise, the commandant organises full searches for duds. Located bombs, shells and grenades are destroyed under officer supervision. Suspected dud areas remain marked until cleared. All troops are warned to report unexploded munitions.

No unit may fire without schedule approval. Past unauthorised firing has caused confusion among other trainees and local workers.

Training at Slapton Sands, Blackpool Sands and the surrounding hinterland fulfils several critical purposes. These areas prepare assault units for combat, rehearse logistics, and test every step of an amphibious landing.

Operation Overlord introduces new tactics and procedures. These require trial, testing and refinement before the invasion. Many techniques do not yet exist and must be created from experience.

The assault itself is only one part of a far larger undertaking. Before troops land, they must be marshalled, embarked and transported across the Channel. Thousands of men gather, are fed, housed and kept ready. Ships and landing craft must be loaded in precise sequence. This is a massive task that demands repeated practice.

Units train through a carefully structured programme. They begin with basic soldiering at small sub-unit level. Training then builds to regimental scale and finally to full assault formations. Specialist assault instruction also takes place at the Assault Training Centre in Woolacombe. There troops work with landing craft, practise demolition and assault weapons, and operate as complete units.

Vehicle handling is drilled constantly. Soldiers drive vehicles on and off landing craft under realistic conditions. Army personnel practise loading, riding in, and disembarking from naval vessels for months. Naval crews train to handle army vehicles and equipment. Purely naval drills cover boat operation, beaching, retracting, and transferring cargo from ships into smaller ferry craft. Every element of amphibious movement is rehearsed long before D-Day.

Slapton Sands provides the space to combine these skills. Here, large formations practise together in full combat scenarios.

| Multimedia |

| Types of Exercises |

Training at Slapton Sands falls into three main categories.

- The first group consists of large, early exercises. Multiple units work together on full assault and supply problems. These cover every phase from mounting to landing and consolidating a beachhead.

- The second group involves smaller, unit-level exercises. These prepare individual formations for their specific roles in the invasion.

- The third group is full dress rehearsals.

Every major American formation destined for Utah and Omaha beaches trains here. The first large amphibious event, Exercise Duck, runs from December 31st, 1943 to January 2nd, 1944. Two further Duck exercises follow, each involving assault units assigned to Omaha. Exercise Fox on March 9th and 10th 1944 continues the Omaha training programme.

For Utah forces, Exercise Beaver in March 1944 and Exercise Tiger in April 1944 train the 4th Infantry Division and the 1st Engineer Special Brigade. These events prepare assault infantry and the complex support elements required on D-Day. Exercise Fabius in early May 1944 provides the final dress rehearsal.

Canadian troops also use the area. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, preparing to land on Juno Beach, conducts a full-scale rehearsal at Slapton Sands.

Many smaller exercises test logistics, supply, and beachhead organisation. Naval gunfire support, air strikes, and even simulated airborne landings feature. Thousands of men, hundreds of vehicles and numerous ships take part. Conditions are made as close to real battle as possible.

Records of these operations survive only in fragments, but together they reveal a vast and complex effort. Slapton Sands becomes the proving ground for the greatest amphibious assault in modern history.

| Exercises Duck |

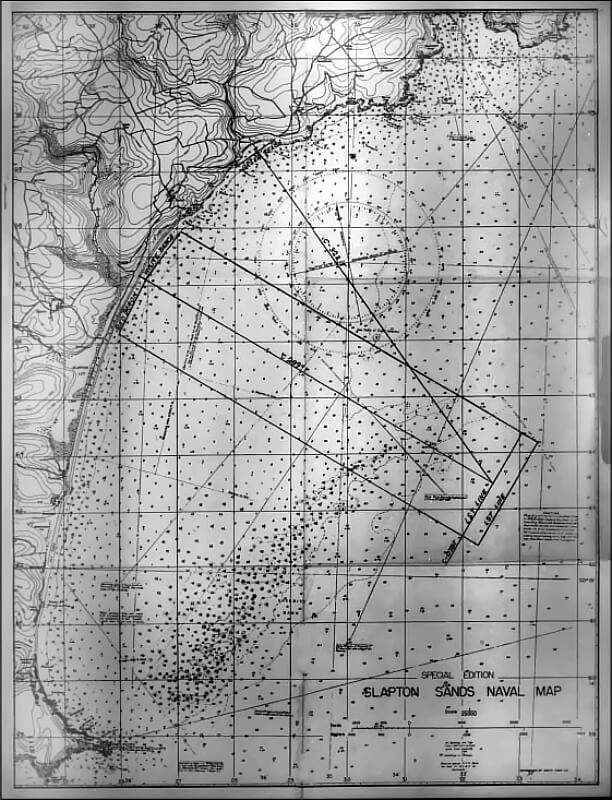

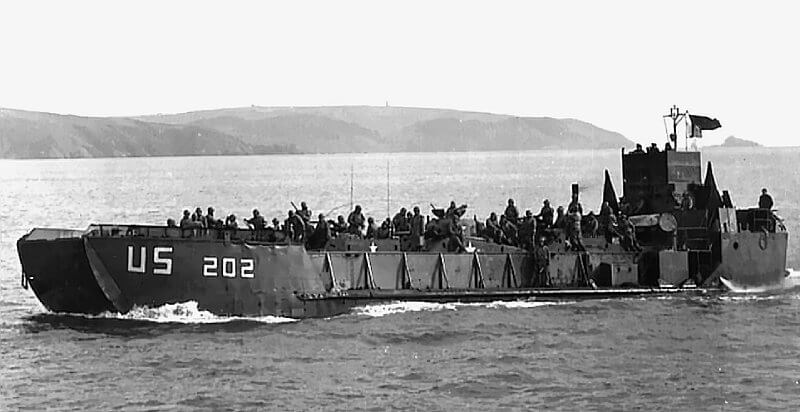

Exercise Duck is the first major United States amphibious training operation at Slapton Sands in Devon. Rear Admiral John L. Hall commands the 11th Amphibious Force. Elements of the 29th Infantry Division of V Corps take part. Four Royal Navy Hunt-class destroyers deliver the naval bombardment. Trawlers and minesweepers escort the convoy and protect the assault area. Bombarding ships and escorts operate under the Assault Force Commander. Distant covering destroyers and coastal craft remain under Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth. The exercise trains every phase of an opposed landing. Forces concentrate, embark, sail, land and seize an inland objective. Hall begins early integration of naval crews with army units. Soldiers and sailors train together across all echelons.

Duck I takes shape during 1943. Initial discussions begin in mid-summer. Formal planning starts in early November. The exercise is first meant for Services of Supply but expands to include all assault phases. The decision to hold it is taken on 21 November 1943. The marshalling plan introduces a new system. Tent camps and vehicle parks line secondary roads near embarkation ports. The arrangement forms long narrow “sausages” on maps. Each site provides hardstandings, meals and basic comfort. Civilian traffic is excluded. The scheme proves highly efficient and later becomes the model for Operation Neptune.

Two phases define Duck I. The first covers troop concentration, processing and embarkation. The second covers the sea passage and assault. The 11th Amphibious Force lifts the 29th Division to Slapton Sands. British naval forces screen against submarines and fast attack craft. Falmouth and Dartmouth serve as embarkation ports. Assembly areas hold troops and vehicles before movement to the hards. Engineers build concrete aprons and ramps for landing craft. Loading tests refine techniques. Troops back vehicles and guns aboard under tight timing. Medium tanks, artillery pieces, trucks and recovery tractors are embarked in varied combinations to measure speed and capacity.

On November 24th, 1943, the Duck I staff meet near Taunton. Daylight execution is chosen for safety and observation. Major General Henry M. Gerow approves the plan on November 25th, 1943. Stocks, installations and final orders follow. Services of Supply requirements are heavy. Over 550 officers and nearly 9,600 enlisted personnel run supply functions. Advanced Headquarters V Corps deploys with the main assault. The 29th Infantry Division embarks with reinforcements. The 1st Engineer Special Brigade, tank and tank destroyer battalions, antiaircraft and chemical units, signal and quartermaster elements, and naval beach parties join the force. Some United States Army Air Forces and Navy units take part.

Embarkation begins six days before the landing and continues until the day before. The Falmouth assault group loads fourteen Landing Ship Tank, thirty-four Landing Craft Tank, five Landing Craft Mechanised and 161 Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel. Dartmouth provides fifty-seven Landing Craft Mechanised. Sea movement starts before D-Day. Slapton Sands represents a defended European coast. Troops embark with full assault scales. Vehicles carry waterproofing. Loading speeds exceed expectations. Stowage plans remain difficult to complete but most loads are embarked successfully.

D-Day for Duck I is Monday, January 3rd, 1944. Naval gunfire opens ninety minutes before H-Hour. Hunt-class destroyers fire with reduced charges and light volume to avoid accidents. Small craft form up and advance behind guide vessels. The first assault wave fans into a wedge at 09:40. H-Hour strikes at 10:00. Eight craft land troops on the northern beach near Manor House. Soldiers disembark almost dry-shod. They remain exposed near the water for about forty minutes, possibly awaiting wire gaps. White phosphorus and Bangalore torpedoes appear as the advance begins. On the southern beach more craft land seven minutes late. Two stick for some time before clearing. Reserve battalions and engineer elements follow. Landing craft of all types continue arriving through the day. Bulldozers tow vehicles through soft sand and hold craft against the tide. Engineers blow gaps at Strete Gate with pre-placed charges. They clear mines, open beach exits and prepare supply routes. DUKW’s and coasters begin unloading stores that afternoon.

Combat units practise clearing pillboxes, mines and wire before pushing inland. Imaginary German positions are detailed and umpires enforce realistic clearance. Fourteen pillboxes mount at least two machine guns each. Other open pits hold additional weapons. The southern sector is notionally mined. Simulated 105-millimetre and 150-millimetre batteries fire from inland. Anti-aircraft guns and an enemy airfield are assumed. Counterattacks appear in the scenario at three, eight and thirty-two hours after landing, including tanks and infantry. No underwater obstacles exist but wire and limited steel obstacles line the shore. Slapton Ley, a wide freshwater lake, delays movement until bridging arrives. Engineers and infantry adapt to the obstacle.

Support services test methods while combat troops advance. Quartermasters trial palletised cargo. Chemical Warfare Service practises decontamination. Engineers lay tracks and strengthen beach roads. Signal Corps deploys loudspeakers to control congestion. Communications expand rapidly but stocks prove short. Beach dumps and fuel points appear but fire protection is weak. Medical units establish a 100-bed field hospital. Military Police direct traffic with mixed success. Sommerfeld track and coir matting surface exits but often fail on soft sand without proper anchoring. Congestion builds where vehicles cannot turn. DUKW’s and cargo trucks share narrow tracks. Recovery tractors work constantly to free bogged vehicles and to anchor landing craft against rising tides.

Camouflage discipline remains poor. Troops move in compact masses across open fields. Mortars, signal lines and supply points stay exposed. Some headquarters pitch tents in the open despite nearby cover. Map supply fails to simulate real amphibious issue. Security breaks down as radio silence is ignored. A radio intelligence team reconstructs the full order of battle from intercepted traffic.

Despite flaws, Duck I achieves much. The marshalling and embarkation system proves sound. Loading is faster than planned. Facilities can handle far larger numbers. The main weakness lies in combined planning, command direction and realistic fire support. Troops bunch under fire and move slowly inland. Beach traffic control needs strengthening. Engineers must clear obstacles faster. Yet the exercise marks a major step in teaching American units amphibious technique.

Blackpool Beach north of Slapton also sees activity. United States Army engineers visit on D+1. They observe maintenance operations, roadways built of Sommerfeld track and matting, and LCT unloading vehicles and stores. Traffic remains confused. DUKWs shuttle supplies. Medical clearing stands inland. Petrol dumps lie about 1.6 kilometres from the shore. Beach congestion is heavy.

Planning for further training begins immediately after Duck I critiques. A permanent combined planning group forms on January 25th, 1944. Duck II follows on February 7th, 1944. Duck III runs from February 23rd, 1944 to March 1st, 1944. These exercises give practice to remaining combat teams of the 29th Division and to 1st Engineer Special Brigade elements absent from Duck I. Duck II focuses on the 116th Regimental Landing Team with supporting engineers. Duck III uses the 115th Regimental Landing Team and adds tanks and tank destroyers. Both repeat Duck I’s basic plan but try to avoid its failures. Camouflage improves and supply handling becomes smoother. Army and Navy coordination still lags. Craft are misplaced, road signs remain scarce and inter-service planning remains difficult. Neptune’s final organisation is not yet fixed, so some unit arrangements differ from the later D-Day scheme.

Exercise Duck transforms Slapton Sands into a vital American amphibious training ground. It provides the first full-scale rehearsal for the 29th Infantry Division and supporting forces. Lessons on marshalling, loading, traffic flow, engineer work, beach logistics and fire support flow directly into the planning and execution of Operation Neptune.

| Exercise Fox |

Exercise Fox is a major amphibious training operation held at Slapton Sands in Devon. Force O conducts the exercise under the command of Major General Henry M. Gerow of V Corps. V Corps issues the order on February 7th, 1944. The event runs from March 7th, 1944 to March 11th, 1944. The assault takes place on March 11th, 1944. Two regimental combat teams form the assault force. Troops embark at Weymouth and Portland, which serve as the Neptune ports for Force O. Attack transports are used for the first time in training. Two cruisers and eight destroyers provide the main naval bombardment. Additional destroyers and trawlers escort the convoy. No German air or sea action occurs during the movement or at Slapton Sands. After completion, the attack transports sail to the Clyde to reduce exposure to air attack. Exercise Fox is the largest rehearsal before Fabius I and Exercise Tiger. It is the only major training event built fully around the developing Neptune plan. Fabius I will follow to refine the Omaha assault.

Planning starts late because Operation Plan Neptune is not issued by First Army until 15 February. Detailed Fox planning begins only after this date. The delay weakens preparation and limits coordination. Many observers later describe Fox as a training event rather than a true full-scale test. They expect Fabius I to correct the weaknesses exposed here.

Marshalling follows the methods developed during Exercise Duck. XVIII District runs the new marshalling areas with fresh personnel. Camps are built but not fully complete when troops arrive. Two assault teams form the landing force. The 16th Regimental Combat Team of the 1st Infantry Division takes one sector. The 116th Regimental Combat Team of the 29th Infantry Division takes the other. The headquarters of the 1st Infantry Division directs the assault on the beach. A V Corps headquarters group oversees the divisional staff. A provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group supports both assault teams. The 37th Engineer Combat Battalion of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade supports the 16th Regimental Combat Team. The 149th Engineer Combat Battalion of the 6th Engineer Special Brigade supports the 116th Regimental Combat Team. Each engineer battalion includes DUKW companies and truck companies with medical, signal, quartermaster and port troops attached. Together these elements form beach parties for each sector.

Units begin moving into Dorset marshalling areas before March 1st, 1944. Construction continues while troops arrive. Embarkation starts on March 7th, 1944 and continues until March 9th, 1944. Ports used include Plymouth, Weymouth, Dartmouth and Portland. The convoy includes six attack transports, twenty-one Landing Ship Tank, twenty-two Landing Craft Infantry (Large) and forty-nine Landing Craft Tank. Numerous Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel and salvage craft also sail. Seven quartermaster truck companies support the movement. They use a standard convoy system on March 7th, 1944 and then a shuttle for the final two days. A total of 16,923 personnel and 1,908 vehicles are processed.

H-Hour craft assemble the night before the landing. They sail for Slapton Sands under escort by five British destroyers. The Royal Air Force and the Ninth United States Air Force provide air cover. The plan mirrors the Omaha phase of Neptune, with the British holding the left and the Americans the right. In Fox, only the American left flank is actually exercised. The 16th Regimental Combat Team lands on the right and the 116th Regimental Combat Team on the left, reversing the order used in Normandy. Planning assumptions add further waves. The 18th Regimental Combat Team of the 1st Infantry Division is assumed to land at H plus two hours. The 26th Regimental Combat Team is assumed to land on D plus one. The 115th Regimental Combat Team is assumed to land on D-Day with the 759th Tank Battalion. Each assault team lands two battalions abreast with one battalion in reserve. The assault landings are generally satisfactory. Naval gunfire uses live ammunition. The follow-on build-up suffers from rushed planning. The 5th and 6th Engineer Special Brigades lack experience and fall behind schedule. Confusion spreads among assault troops as supply and support lag.

Observers note weaknesses during the mounting phase. Camp staffs lack training but improve rapidly. Camps have only two and a half days to prepare before troops arrive. Static staff trained during Fox are kept for later exercises. Early mess sanitation is poor. Cooking schools open to improve food service. Kitchens receive new equipment and sanitation rules. Transport standing orders are complex and require too many forms. Military Police supervision is heavy-handed. Loading standards allocate four hours per Landing Ship Tank, but actual loading takes about two hours.

Critiques of the assault highlight further problems. Coordination between the Navy and the Army is weak. Links between higher headquarters are also poor. Short planning time is a major cause. Security is inconsistent. Camouflage is poor and camp control weak. Telephone systems for air raid and gas warnings fail often. Emergency communications are improved after Fox. Neptune communication plans are adjusted as a result.

Beach Group performance draws the sharpest criticism. There are too few loading points for the number of craft. Coordination between beach masters and coasters is ineffective. Supplies reach the shore late. Cargo from coasters arrives damaged. Many coaster captains have no clear orders. For several hours there is no contact between Beach Group and naval control. Beach communications fail to link headquarters to supply dumps until the day after the landing. Wire-laying teams must work at night due to shortages of material. Twenty DUKWs are allocated to each coaster, but only ten prove necessary to unload them. Later troop waves land in the wrong sequence, adding to confusion. Medical clearing units come ashore at H plus two hours but their equipment does not arrive until H plus eleven, leaving them unable to operate.

Several positive results emerge. Fifteen DUKW’s land preloaded with balanced ammunition for immediate issue, and the system works well. This method is adopted for Neptune. Waterproofing standards improve further. All vehicles are fully waterproofed and later de-waterproofed ashore. New sealing compounds and techniques prove effective. The exercise shows clear progress in these technical areas.

Exercise Fox, despite its rushed planning and coordination faults, provides the first large rehearsal for Force O under the actual Neptune framework. It reveals weaknesses in staff integration, security, and beach logistics. It also advances key techniques such as vehicle waterproofing and preloaded DUKW ammunition supply. The lessons flow directly into later full-dress rehearsals, especially Exercise Fabius I, which will refine the assault plan for Omaha Beach.

| Exercise Muskrat |

Force U, destined for Utah Beach, begins intensive training with Exercise Muskrat. Muskrat itself is split into two parts. Muskrat I runs from March 13th, 1944 to March 23rd, 1944. The 12th Regimental Combat Team of the 4th Infantry Division embarks at Plymouth on three attack transports. The ships sail north to the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. There the regiment conducts battalion landing team training focused on ship-to-shore movement and naval coordination.

Muskrat II follows from March 24th, 1944 to March 26th, 1944. The 12th Regimental Combat Team is reinforced by a detachment from the 1st Engineer Special Brigade. The force continues battalion landing team assaults. Two cruisers provide bombardment while destroyers, corvettes and trawlers escort the convoy. Rear Admiral Don P. Moon sails in U.S.S. Bayfield to observe. Captain Maynard commands the attack transports as task force commander. Planning friction appears. Officers borrowed from Force O write the orders without consulting the commander, who is away watching Muskrat I and cannot coordinate by telephone. These same officers must also prepare plans for Exercise Beaver under heavy pressure.

| Exercise Otter and Mink |

Other battalion-level drills of Force U run on the Devon coast. Otter I takes place from March 15th, 1944 to March 18th, 1944. The 3rd Battalion of the 8th Regimental Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, reinforced for beach work, trains at Slapton Sands. Troops embark at Dartmouth, receive one day of instruction and then conduct two daylight assaults. Otter II follows from March 19th, 1944 to March 22nd, 1944, using the 1st Battalion of the 8th Regimental Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division. The 2nd Battalion of the 8th Regimental Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, in reserve during Operation Neptune, does not stage a separate exercise.

Mink I runs at the same time as Otter I, from March 15th, 1944 to March 18th, 1944. The 1st Battalion of the 22nd Regimental Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division trains at Slapton Sands with a plan mirroring the Otter scheme. Daylight assaults test coordination between battalion infantry and beach engineers. Mink II runs from March 19th, 1944 to March 22nd, 1944. The 2nd Battalion of the 22nd Regimental Combat Team repeats the plan while the 3rd Battalion also stays in Neptune reserve.

| Exercise Beaver |

Exercise Beaver runs from March 29th, 1944 to March 31st, 1944. The 8th and 22nd Regimental Combat Teams of the 4th Infantry Division participate. A detachment of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade reinforces them. Two companies of the 1106th Engineer Group also join. The 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment takes part. The Ninth Air Force, under Major General Barton, supports with attached units.

Forces load at Plymouth, Dartmouth and Brixham. They sail in Landing Ship Tank and Landing Craft Infantry (Large). The approach follows a circular route around western Lyme Bay. Two cruisers and four destroyers deliver bombardment. Other available ships act as escorts and covering forces. Two minesweeping flotillas sweep ahead of the assault convoy.

The plan mirrors the earlier Duck exercises. Marshalling and embarkation centre on the Brixham–Plymouth district. Slapton Sands serves as the assault area. Group 2 of the 11th Amphibious Force provides the lift. It protects the convoy and supports the landing. Earlier exercises are ordered by VII Corps but run largely by the 4th Infantry Division. Beaver sees VII Corps actively involved.

Disembarkation runs to plan. The beach assault also runs to plan. Assault units secure a bridgehead quickly. They advance inland at speed. After the D-Day advance, units reorganise for extended operations. Resupply is carried out promptly. About 1,800 tonnes of supplies unload from two coasters. Combat units receive ammunition resupply on D-Day night.

Exercise Beaver is considered disappointing. Confusion is evident in several phases. Some units fail to complete assigned missions.

| Exercise Cargo V |

Exercise Cargo V runs from April 1st, 1944 to April 11th, 1944. The 6th Engineer Special Brigade practises beach and dump development at Slapton Sands. Engineers build exits, lay tracked roads and prepare inland dumps. They test rapid unloading of vehicles and stores and the organisation of supply distribution under combat conditions.

| Exercise Trousers |

Exercise Trousers is a major amphibious training operation for the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, forming Force J for the Juno Beach assault on D-Day. It takes place on April 12th, 1944 on the coast between Dartmouth and Newton Ferrers. The aim is to train the naval assault force in the passage, approach and landing of troops. Signal communications and fire support during an opposed assault are also tested.

The 2nd Canadian Corps commands the operation. Under it serves the 4th Special Service Brigade, reduced by three commando units. The corps is tasked to land, advance and secure by last light a covering line from Totnes to Brixton. Two brigades of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division assault the right flank. A simulated brigade from the 1st Canadian Infantry Division represents the left. A special formation called Bing Force takes part. Bing Force includes armoured cars and Royal Engineers. Its role is to land once the coastal defences are reduced, push inland, destroy the bridge over the River Avon, delay any counter-attack and then withdraw on the Force Commander’s orders.

The beaches are codenamed Able and Baker. The 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group lands on Baker. The 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group lands on Able. The 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group remains in reserve. All loading is carried out from Southampton. Landings are planned to complete on the first tide and to finish when the divisional intermediate objective is reached.

The plan is divided into two phases.

- Phase I captures the beachhead.

- Phase II secures the divisional intermediate objective inland.

- After the beachhead is formed, the force advances to a pre-set safety line. No troops or vehicles pass this line until H plus 120 minutes. This restriction follows Slapton’s live fire safety rules.

Naval command uses four headquarters ships. H.M.S. Hilary carries the 3rd Canadian Division headquarters. H.M.S. Lawford carries the 7th Brigade headquarters. H.M.S. Waveney carries the 8th Brigade headquarters. S.S. Isle of Thanet carries the 9th Brigade headquarters. The landing fleet includes nine Landing Ship Tank, twenty Landing Ship Infantry, one hundred and ten Landing Craft Tank and twelve Landing Craft Infantry. Two cruisers, four destroyers and many smaller craft provide support.

The assault sequence begins sixty minutes before H-Hour when destroyers move inshore. At H minus forty, the destroyer bombardment starts. At H minus thirty, self-propelled artillery opens fire. Between H minus twenty-five and minus fifteen, aircraft attack simulated field artillery positions. At H minus twenty, Landing Craft Gun provide flank protection. At H minus fifteen, armoured Landing Craft Tank fire high explosive at beach defences, followed by rockets from Landing Craft Tank (Rocket). At H minus five, Duplex Drive tanks land and fire as aircraft strafe the beaches. At H minus two, Landing Craft Assault (Hedgerow) fire their mortars. At H-Hour, Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers and LCT(A) touch down.

Five minutes after H-Hour, assault companies land while supporting fire continues under forward observers. By H plus fifteen, the locality at grid 262673 is taken. By H plus twenty, the locality at 251655 falls and reserve company elements land. Battalion headquarters follow. At H plus thirty, the Advanced Beach Signal Station is established. At H plus thirty-five, destroyers fire on targets identified by forward observers. Positions at 236683 and 244686 are captured by H plus forty. At H plus forty-five, the Main Beach Signal Office is operational. By H plus fifty, Beach Sub Sectors are organised on Able and Baker. The beachhead is declared secure by H plus sixty, and Bing Force comes ashore.

Between H plus sixty and seventy-five, first priority vehicles land. By H plus eighty-five, Widdicombe Ho and Beeson are cleared. At H plus ninety, self-propelled artillery comes ashore and Bing Force advances inland. At H plus one hundred and twenty-five, forward elements reach the report line “Snake”. By H plus one hundred and thirty, self-propelled artillery prepares new missions further inland. At H plus one hundred and forty, the remaining assault brigades land. Orders for the reserve brigade to land are issued between H plus one hundred and fifty and two hundred and ten. By H plus two hundred and thirty, the divisional intermediate objective is secured.

| Multimedia |

| Exercise Tiger |

Exercise Tiger is the final full-scale rehearsal for Force U before the Normandy landings. It tests the Utah Beach assault plan under conditions as close to the real operation as possible. Planners face limits in equipment and training grounds but aim to mirror Operation Overlord faithfully.

The Utah assault is treated as a separate undertaking from the British and Canadian landings. Those forces train in the Fabius series. Force U, built around the United States VII Corps, requires its own rehearsal. Preliminary planning begins early in February 1944. Definite instructions are issued on April 1st, 1944. Tiger follows the methods of Exercise Beaver but expands in size. It uses many of the same landing craft that will carry the troops to Normandy.

The assault route runs deep into Lyme Bay to give a long sea passage. Minesweepers place lighted dan buoys to mark approach lanes. Two cruisers and seven destroyers provide bombardment from fifty minutes before H-Hour until the assault begins. The escort and covering force is the largest yet, using every available destroyer, corvette and trawler. Commanders stress clear communication between supported and supporting elements. Camouflage discipline is enforced in marshalling areas and during movement.

Tiger involves about twenty-five thousand men and two thousand seven hundred and fifty vehicles. It runs from April 26th, 1944 to April 30th, 1944. All troops process through concentration and marshalling camps. They load the same scales of weapons, vehicles and supplies planned for D-Day. The United States Navy controls the cross-Channel movement. Naval and air fire plans copy Overlord as closely as ammunition and weather allow.

The 4th Infantry Division provides three regimental landing teams. Two embark at Dartmouth, Brixham and Torquay. One embarks at Plymouth. The 1st Engineer Special Brigade supports directly. XIX District manages the mounting and camp organisation, correcting problems seen in Duck and Beaver. The 11th Amphibious Force provides the lift. A detailed medical plan tests casualty evacuation. Umpires tag soldiers as wounded and send them through the chain to beach battalion medical posts and ships.

The planned airborne element cannot be fully staged. Aircraft are scarce and Slapton has training limits. Instead, four hours before H-Hour, troops of the 101st Airborne Division arrive by vehicle to simulate a drop east of Kingsbridge. They seize high ground west of the beach. Three naval shore fire control parties join them. Nine more from the 286th Joint Assault Signal Company work with the 4th Infantry Division. The Ninth Air Force sends three air support parties. The 82nd Airborne Division is simulated to land on the following day west of Ermington to block enemy reinforcements.

Tiger unfolds in four phases. Phase one on April 26th, 1944, sees troops move to concentration areas, pass through marshalling and embark. Phase two on April 27th, 1944 covers the convoy sailing, debarkation and the beach assault to secure the first line. Phase three on April 28th, 1944 consolidates the beachhead and prepares for redeployment. Phase four on April 29th, 1944 completes unloading and beach maintenance.

Concentration centres on Dartmouth and eastern Plymouth. Embarkation takes place from Dartmouth, Brixham, Torquay and Plymouth. Service ammunition is live. Naval and air units fire in accordance with the Overlord plans. Weather is good when the landings begin.

Planning delays cause problems. Some loading tables are rewritten mid-operation. Naval craft reach the hards late, creating jams and confusion. Despite this, the beach assault itself runs to plan. Naval bombardment suppresses pillboxes and cuts wire. Infantry land and link up with the simulated airborne troops inland. Engineers follow quickly. They sweep mines, open exits, lay tracked roads and build supply dumps.

Unloading begins on D-Day under the eyes of First Army and the Services of Supply. First Army orders 2,200 tonnes of stores ashore in the first two days. On the first tide two Landing Craft Tank each land 200 tonnes beyond the high-water line. On the second tide two coasters land 1,500 tonnes. On the following day six large barges each bring fifty tonnes.

Captain Harry Butcher, naval aide to General Eisenhower, observes the landings. H-Hour is planned for 07:30 unless weather prevents air support, in which case it moves to 07:00. Bombardment begins on time. The sea is calm. Landing Craft Tank with Duplex Drive tanks prepare to launch at 07:15. Suddenly H-Hour is postponed by one hour even after bombardment starts. Infantry in Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel land with or just after the tanks. Rocket craft fire diagonally to clear wire and obstacles. Tanks wait while engineers blast gaps and remove obstructions. Butcher notes that, under real fire, the close-packed tanks and craft would have been easy targets.

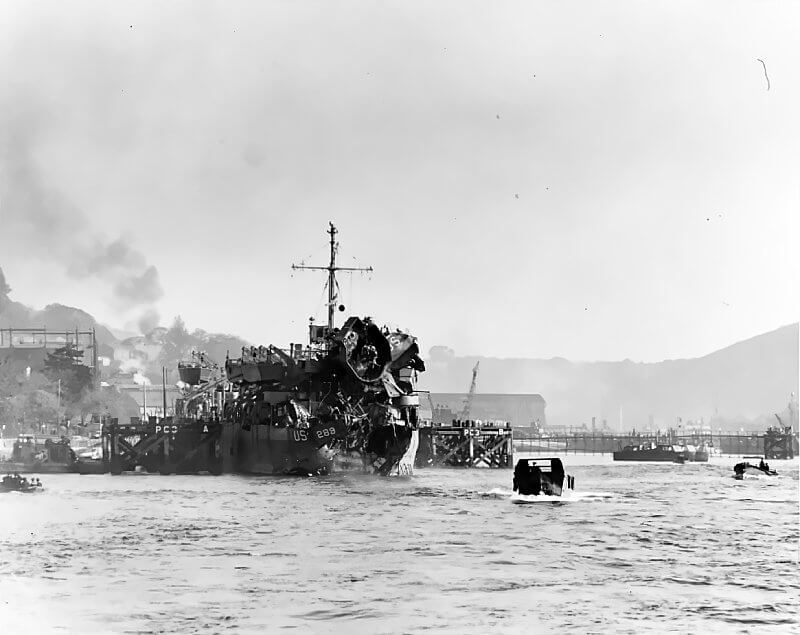

In the early hours of 28 April 1944, disaster strikes the rehearsal for the Utah Beach landings. Long before the planned assault, nine German E-boats slip from Cherbourg under the cover of darkness. These fast S-boats move silently into Lyme Bay, hunting the slow convoy of Landing Ship, Tank that carries troops and equipment for Exercise Tiger.

The convoy, code-named T-4, consists of eight Landing Ship Tank packed with combat engineers, vehicles, fuel, ammunition and support troops. Their role is to follow the initial assault and build the beachhead. Escort and communication arrangements prove dangerously weak. The destroyer H.M.S. Scimitar, meant to cover the convoy, is absent after suffering damage. The remaining British escorts and the American landing ships operate on different radio frequencies and cannot coordinate effectively.

At about 01.30 the first torpedoes are launched. The E-boats split into attacking pairs and strike in coordinated salvos against the dark column of landing ships. LST-507 is one of the first to be hit. A torpedo tears into her side at about 02.03. Fire erupts as fuel and vehicles ignite. Smoke and flames trap men on deck. Soldiers and sailors are blown overboard or forced into the cold sea.

LST-531 is struck soon after and sinks within six minutes. Another Landing Ship Tank is damaged but manages to escape. The rest scatter under fire. The surviving ships fire back but the E-boats withdraw swiftly into the night before any organised counter-attack can form.

The human cost is devastating. In the exercise as a whole at least 749 men die, including 551 from the United States Army and 198 from the United States Navy. From LST-507 about 202 men are lost. LST-531 claims around 424 lives as it plunges beneath the surface. Many victims drown or die of hypothermia while waiting in darkness for rescue. Others are trapped in the burning wreckage or lost under collapsing decks.

By dawn the attack is over. The surviving landing ships limp back, their decks scarred by fire and explosion. The disaster exposes serious flaws in escort planning, radio coordination and convoy protection. It casts a long shadow over Exercise Tiger but also drives urgent changes before the real landings at Utah Beach.

The loss of the landing ships during Exercise Tiger severely damages Allied capacity for follow-up reinforcement and supply. The disaster reveals how vulnerable slow Landing Ship Tank are when faced with fast German torpedo craft. Senior commanders recognise the danger of a similar night attack during the real invasion and the potentially catastrophic effect on the build-up of forces at Utah Beach.

Immediate changes follow. Radio and signal procedures are standardised so that escorts and landing ships can communicate reliably. Lifejacket and survival training is improved after many soldiers drown through incorrect use of inflatable belts. Escort doctrine for slow convoys is rewritten, giving greater emphasis to close protection and better radar and patrol coverage.

Despite the scale of the loss, strict secrecy surrounds the event. Commanders fear that news might damage morale or reveal weaknesses in Operation Overlord. Survivors are sworn to silence. Intelligence officers urgently search for ten men with “BIGOT” clearance, the highest level of knowledge about the invasion plans, who are missing and presumed dead. Their disappearance raises concern over possible compromise of the D-Day operation.

Critiques judge the mounting and landing broadly satisfactory but warn of complacency. After many rehearsals some officers treat Tiger as routine. Coordination and timing problems are ignored with the belief they will not occur on D-Day. Yet improvements appear. Camp operations run more smoothly than in earlier exercises. Briefing tents remain too few but overall security improves. Camouflage is stronger. Signal installations perform well. Weaknesses remain: late orders, poorly controlled yellow-painted fuel cans visible from the air and confused camp pass systems.

Losses from the E-boat attack are replaced in May. The 3206th Quartermaster Service Company, almost destroyed, is replaced by the 363rd Quartermaster Service Company. The 557th Quartermaster Railhead Company is replaced by the 562nd Quartermaster Railhead Company.

| Multimedia |

| Exercise Fabius |

Exercise Fabius is the final and largest rehearsal before Operation Overlord. It follows immediately after Exercise Tiger and becomes the most extensive amphibious training ever staged. While Tiger prepares Force U for Utah Beach, Fabius trains every other assault and build-up force for the Normandy invasion.

Fabius is divided into six linked exercises.

- Fabius I prepares Assault Force O, the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions, the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group and attached units, for Omaha Beach under V Corps. These forces marshal in Area D, embark from Portland and Weymouth, and land at Slapton Sands.

- Fabius II trains Assault Force G, the British 50th Infantry Division and supporting troops, for Gold Beach, marshalling in Areas C and B, embarking from Southampton and Lymington, and landing on Hayling Island.

- Fabius III prepares Assault Force J, the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division and attachments, for Juno Beach, marshalling in Areas A and C, embarking from Southampton and Gosport, and landing at Bracklesham Bay.

- Fabius IV trains Assault Force S, the British 3rd Infantry Division and attachments, for Sword Beach, marshalling in Area A and the South-East Command, embarking from Gosport and Portsmouth, and landing near Littlehampton.

- Fabius V rehearses the British build-up for Gold, Juno and Sword with shipping from the Thames and east coast ports.

- Fabius VI does the same for American and British build-up forces leaving southern ports. The Americans use half of Area D with Portland and Weymouth; the British use half of Area C with Southampton.

Fabius I to IV run simultaneously under 21st Army Group. They begin on April 23rd, 1944 and end on May 7th, 1944. From April 23rd, 1944 to April 26th, 1944, troops detach residue parties and receive final briefings. Marshalling starts on April 27th, 1944. Loading takes place on April 29th, 1944 and May 1st, 1944. D-Day is first planned for May 2nd, 1944, but delayed twenty-four hours because of weather. Fabius V and VI, planned for May 4th, 1944 to May 6th, 1944, also finish on May 7th, 1944, after postponements. Each national command plans its own section but higher coordination remains tight. The account here focuses on the American rehearsal, Fabius I.

By this stage experimentation ends. D-Day is weeks away. Units will not return to home stations but stay in marshalling camps ready for the real assault. There is no time to rewrite plans or retrain deeply. Minor faults may be corrected, but the structure is fixed. Fabius is intended to give troops final experience and to prove the invasion system can function as one machine.

About twenty-five thousand soldiers pass through marshalling, embark and land at Slapton Sands before returning to await Overlord. By the close of Fabius the invasion machine is largely proven. Weaknesses are clear and recorded but there is no time for deep redesign. Troops and ships return to marshalling areas and wait for the real assault on Normandy.

| Multimedia |

| Conclusion |

With the completion of the amphibious training programme, the Slapton Sands Assault Training Area is no longer required for military use. Plans begin to return the district to civilian occupation.

Local people have long known of the heavy wartime activity but are told little about the exercises inside the restricted zone. By late April 1944 Admiral Sir Geoffrey Leatham, Commander-in-Chief Plymouth, raises the question of preparing for handover once the American forces leave. On July 8th, 1944 Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith, Chief of Staff at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, informs Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsay, Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force, that the area will not be needed for further assault training provided the Studland and Woolacombe ranges remain available. The district can therefore return to civilian use once declared safe.

Responsibility for reinstatement is debated inside the British Government. Several ministries are involved, including the Ministry of Works, the War Office, the Admiralty and the Ministry of Agriculture. It is decided that the Admiralty, which carried out the original requisition, will remain the lead authority for restoration and compensation. The Treasury recognises the exceptional nature of the evacuation and agrees that government action is required to help residents return and rebuild their livelihoods. The United States Army, having benefited from the training grounds, is expected to assist.

Reinstatement is divided into three fields: land, public utilities and buildings. Land that has seen only light or temporary use is left for farmers to restore with compensation payments. Fields where farming has been badly damaged and individual recovery is impractical fall under the Ministry of Agriculture, which will rehabilitate soil and replace fencing. Public utilities such as water, sewage and transport are handled by the Ministry of War Transport and the Ministry of Health, with support from local councils. Buildings that are completely destroyed are to be compensated in cash rather than rebuilt. Repairable but uninhabitable houses will be restored only to a basic habitable standard to conserve labour and cost.

Shortage of manpower poses a serious difficulty. Post-bombing reconstruction after German V-1 attacks has already stretched resources. A July 1944 meeting with local farmers shows that less reconditioning will be needed than first expected and many farmers are ready to repair their own land.

On July 4th, 1944 a formal planning conference meets at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force Headquarters, Norfolk House, St James’s Square, London. Sir Findlater Stewart chairs the session with General Sir Hugh Elles, the Regional Commissioner, and representatives from all concerned ministries. They agree that postal services, fuel and coal distribution, electricity, sewage systems and roads must be restored before full reoccupation. Devon County Council, helped by the Ministry of Transport, will handle road repair. The Admiralty will direct overall reinstatement, using other departments to supply materials and labour. Regional and local authorities are ordered to provide extra support.

Returning farmers quickly to their land is a top priority to restart food production. Clearance of unexploded ordnance and other hazards must be finished before any civilian return. Safety certification is planned for August 1st, 1944. About 1,000 American troops are assigned to remove mines, shells, barbed wire and other debris.

The restoration programme aims to make houses and farmland usable rather than restore them fully to pre-war condition. Remaining damage will be covered by compensation claims. Information offices reopen to coordinate the return of people, livestock and possessions. Local transport firms, vital during the 1943 evacuation, are again mobilised to help repatriate residents.

By late July 1944 regional officials and press representatives inspect the area. Reports describe mostly superficial damage: broken windows, damaged doors, overgrown gardens and neglected roads and hedges. Some coastal buildings, including the Royal Sands Hotel and Strete Gate Manor, are destroyed by shelling. Sections of the stone wall along the Strete road are badly damaged. Stokenham shows moderate harm, with roof loss to the parish church and heavy damage to the Church House Inn. Torcross and Chillington suffer less, and inland villages escape with minor effects. Naval bombardment and live-fire training cause inevitable local destruction, but most settlements remain structurally sound.

Vegetation has overrun abandoned land. Some roads have crumbled. Rodents are common after the long vacancy, and pest-control teams are organised. Public utilities such as telephone lines are among the first restored; General Post Office engineers return early to reconnect service.

By late summer 1944 the Slapton Sands Assault Training Area is formally released from military control. Plans for phased civilian return are in place. Agricultural work is prioritised. Essential services are being restored. The great temporary transformation of South Devon into a vast assault training ground ends, and the process of returning the district to normal life begins.

| Multimedia |

| Sources |

It’s in point of fact a nice and useful piece of information about this training facility. Thank you for sharing.