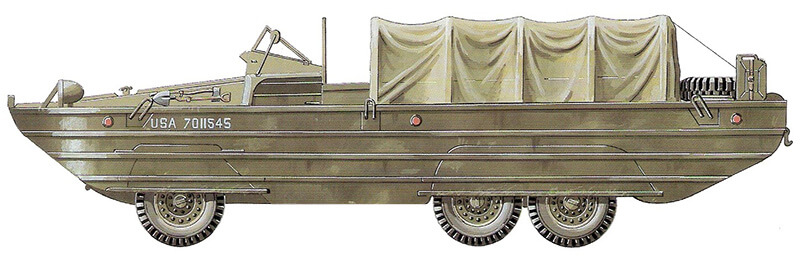

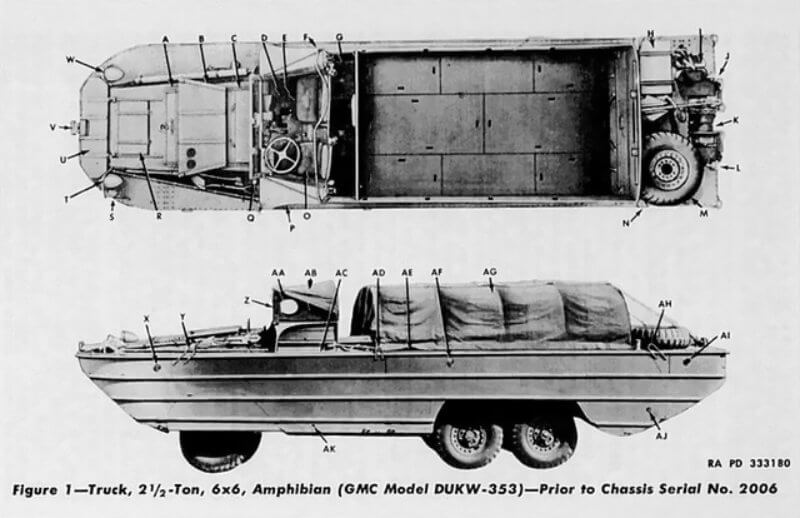

| Length |

| 9.45 metres |

| Wide |

| 2.49 metres |

| Height |

| 2.69 metres |

| Weight (Loaded) |

| 9,100 kilograms |

| Propulsion |

| GMC Model 270 91 hp (68 kW) |

| Armour |

| – |

| Armament |

| Fittings for a machine gun mount (M36 type) for anti-aircraft defence. |

| History |

The first design for the DUKW is drawn in 1941 by Rod Stephens Jr., a yacht designer from Sparkman & Stephens, Dennis Puleston, a British deep-water sailor residing in the United States, and Frank W. Speir, a Reserve Officer detached from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At this time, the United States is not yet involved in the war, and there is no pressing requirement for such a vehicle.

Nevertheless, the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) and the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) sponsor the project, anticipating future amphibious operations. The aim is to create a vehicle capable of carrying cargo from ship to shore and continuing inland without pause. The team includes Rod Stephens Jr. of Sparkman & Stephens yacht designers, Frank W. Speir of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and British deep-water sailor Dennis Puleston.

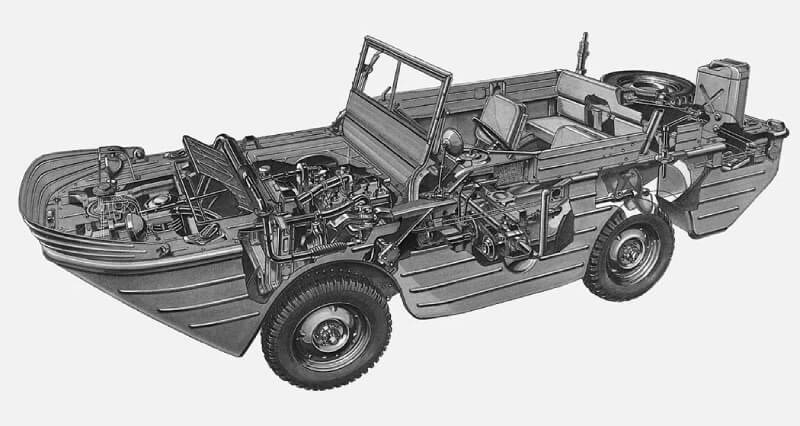

Their first effort is the “Seep” (Sea Jeep), an amphibious variant of the quarter-ton Ford GPA Jeep. It is intended to ferry soldiers between ships and shore. In calm waters and on narrow roads, it performs adequately. In open water or surf, it proves dangerous. The Seep is unstable, hard to steer, and capsizes in heavy waves. A better solution is needed.

| Multimedia |

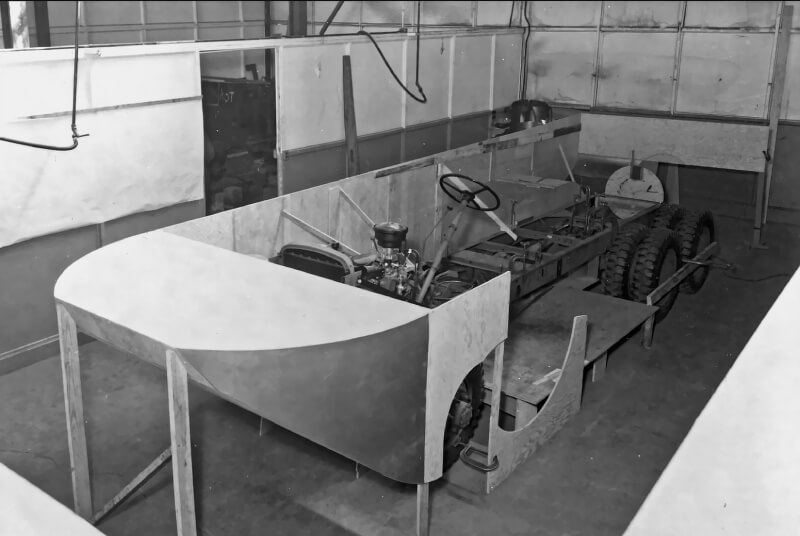

Palmer C. Putnam of the National Defense Research Committee leads a renewed effort. He requests a much larger amphibious vehicle capable of operating on both land and sea, with the command: “Build me a truck that can swim!”

General Motors Corporation is tasked with constructing the prototype. The design is built around the GMC ACKWX, a cab-over-engine version of the CCKW 2½-ton six-wheel-drive lorry, already widely used by U.S. forces. The use of an existing drivetrain, engine, and axles ensures compatibility and simplifies maintenance in the field.

In June 1942, tests are conducted in Chesapeake Bay, the Atlantic Ocean, and inland at Fort Belvoir and Fort Eustis. The DUKW handles surf, currents and cross-country terrain. In July, a successful demonstration at Fort Story leads to official approval.

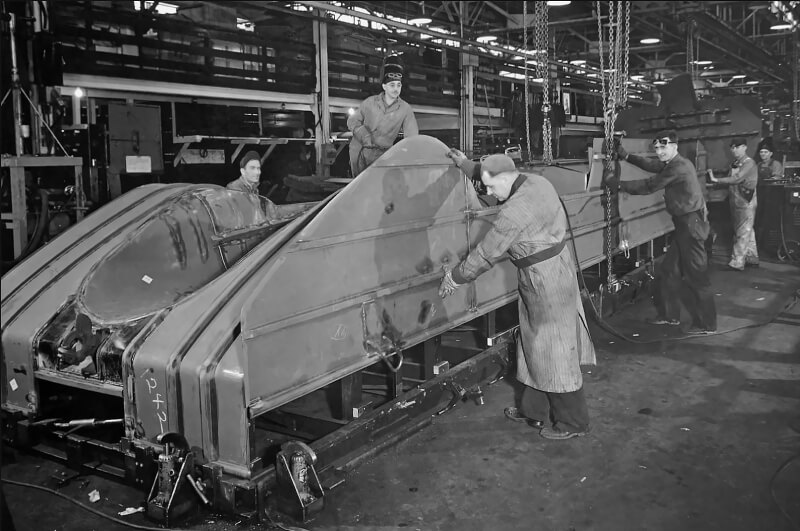

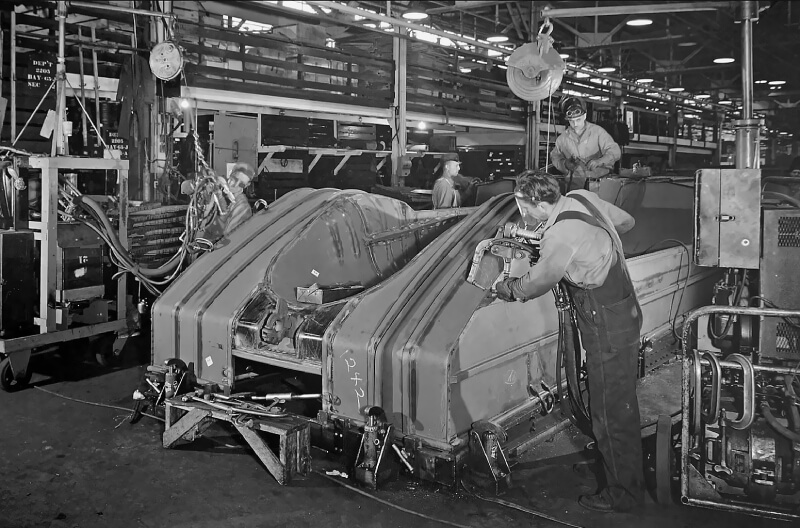

The military initially resists the idea. However, a rescue incident off Provincetown, Massachusetts changes opinion. A United States Coast Guard vessel runs aground on a sandbar during a gale. Wind reaches 110 kilometres per hour, with rain and heavy surf. No other craft can reach the stranded men. A prototype DUKW, present for testing, drives into the sea and rescues all seven crew members. With this, the DUKW proves its worth. Following this, orders are placed. Production begins in late 1942 at Yellow Truck & Coach in Pontiac, Michigan, with further units assembled by Chevrolet in Saint Louis.

Though lightly built and unarmoured, the DUKW combines land mobility, waterborne capability, and logistical flexibility. It becomes a vital asset in amphibious warfare, bridging the logistical gap between ship and shore under combat conditions. The DUKW is officially designated as DUKW 353, 2,5 ton, 6×6, Amphibious Troop/Cargo carrier. The name DUKW came from:

- D. Identified the model year (1942) in General Motors’s coding. The DUKW was developed and first produced in 1942; General Motors assigned the letter “D” to that year, so any vehicle beginning with “D” came from the 1942 series.

- U. Stood for “utility”, indicating the vehicle’s body style as a general‑purpose amphibious cargo truck. In General Motors’s nomenclature this letter signified a utility‑type body that could operate on land and water.

- K. Denoted all‑wheel drive. The DUKW was derived from a six‑wheel‑drive 2½‑ton truck; in General Motors’s code the letter “K” identified vehicles with powered front axles, meaning all the wheels could be driven.

- W. Stood for twin (tandem) rear axles. The DUKW used two powered rear axles, and General Motor’s code marked such vehicles with “W”.

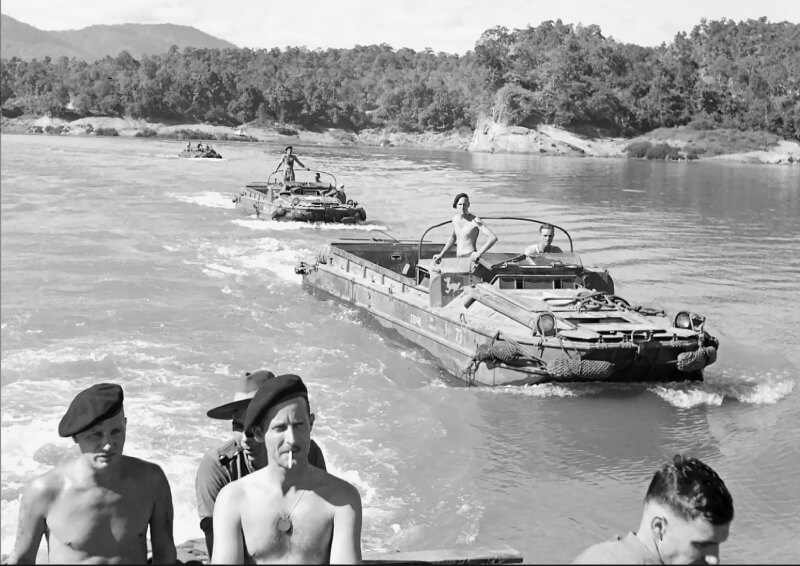

Troops quickly noticed that the letters sounded like “duck,” and the nickname stuck. A total of 21,147 DUKW’s are produced before manufacturing ends in 1945. The British Army receives roughly 2,000 DUKW’s. Canadian forces employ approximately 800, and the Australian Army operates 535, notably during campaigns in New Guinea. The Free French make use of DUKW’s during Operation Anvil–Dragoon and later in mainland Europe.

The Soviet Union receives 589 DUKW’s through the Lend-Lease programme. Soviet units employ them in river crossing operations and in the marshy Pripet region. The vehicle’s performance in swampy and semi-aquatic environments confirms its exceptional versatility.

| Multimedia |

| Multimedia |

| Multimedia |

| Description |

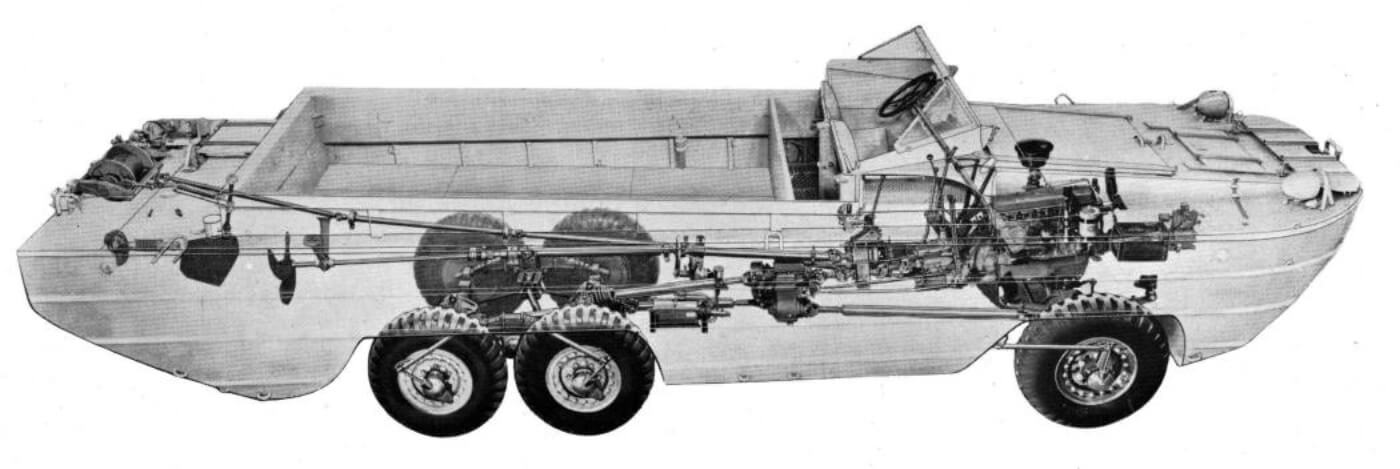

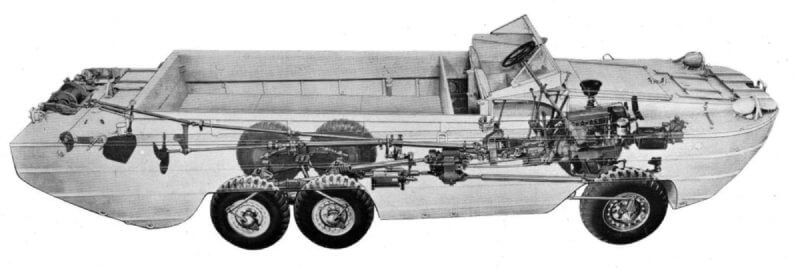

A watertight steel hull is welded around the chassis. It is rectangular with a curved bow, sloped ends, and a flat bottom. Reinforcement beams provide structural strength. The bow and stern are shaped to maximise the approach and departure angles.

Roughly one-third of the vehicle’s length houses the engine. The remainder comprises an open-topped driver’s compartment and a covered cargo area. The powerplant is a GMC Model 270 straight-six petrol engine with 4,425 cubic centimetres of displacement. It delivers 64 horsepower and high torque, ideal for heavy loads.

The gearbox features ten forward speeds and two reverse gears. A long transmission shaft powers a screw-type propeller, mounted in a tunnel at the rear. Steering in water is achieved with removable rudders. The vehicle reaches 80 kilometres per hour on land and cruises at 5.5 knots in water.

The DUKW’s hull is unarmoured, made from steel between 1.6 and 3.2 millimetres thick. A high-capacity bilge pump system is fitted to compensate for this vulnerability, capable of removing up to 1,135 litres per minute in the event of hull penetration.

The cooling system proves complex. After testing nearly 50 combinations of fans and radiators, a final solution is adopted. Air enters behind the driver, flows through the radiator, and exits through side ducts. An integrated heating system prevents bilge water from freezing. Engine heat is circulated through the hull, including the deck and cargo bay.

One of the most significant innovations is Speir’s tyre pressure regulation system. The driver can adjust tyre inflation from the dashboard, improving mobility on soft ground such as sand. This feature, critical for beach landings, becomes standard in many post-war military vehicles.

The cab is made from plywood, fitted with a windscreen developed by Henry Gassaway of Libbey Glass. At the driver’s left, provision is made for a ring mount carrying a .50 calibre machine gun. The cargo area, rated at 2½ tons, is typically covered by a tarpaulin.

| Training |

The United States Navy is unable to train enough personnel to operate all the landing craft entering service. In 1942, the Army takes over responsibility for the DUKW. The First Engineer Amphibian Command is formed that summer.

Army training takes place at Aquatic Park, near the San Francisco Port of Embarkation. Stevedores and soldiers train jointly. There is no model to follow. Equipment must be sourced, personnel recruited, and instruction methods devised from scratch. A Boat Training Centre is opened at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts. Civilian boatbuilders assist by teaching engine maintenance and harbour craft handling.

The initial training course lasts three weeks. It quickly becomes clear that this is too short. Even after two months, many soldiers are unready for wartime operation.

To address this, instructors and maintenance officers attend General Motors’ War Products School from autumn 1943. Over 1,000 instructors receive specialist training in marine engines, shore logistics, and amphibious operations.

| Multimedia |

| Versions |

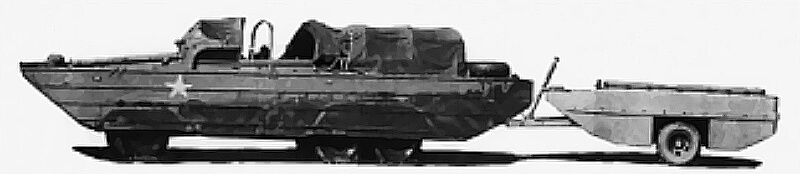

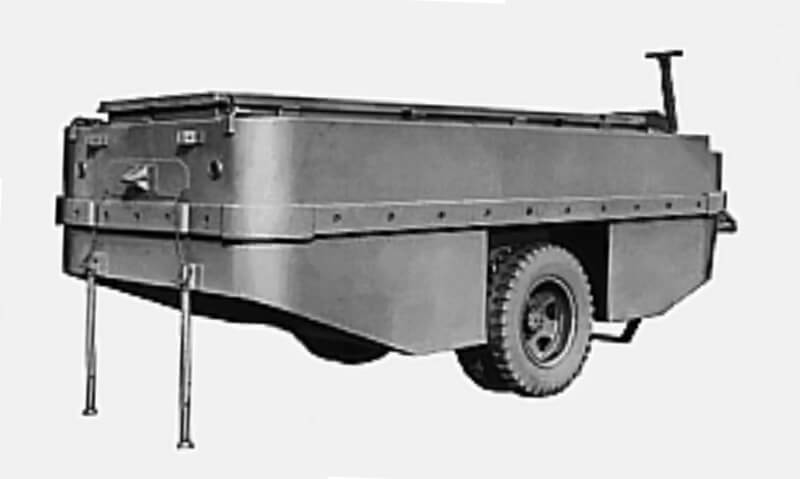

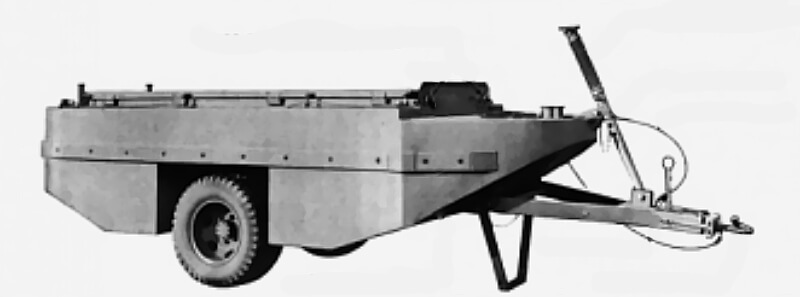

Due to their light construction, DUKWs are not used in initial assault waves. Although tracked amphibious vehicles often spearhead initial landings, DUKW’s are used in large numbers to follow up with supplies. Their chief advantage lies in their ability to transition from sea to shore and continue inland without the need for unloading facilities. They ferry ammunition, fuel, food, and even heavy equipment such as 105-millimetre howitzers. In some instances, DUKW’s are converted into improvised self-propelled guns, despite the chassis struggling under recoil stress.

Other versions mount over one hundred 4.5-inch rockets for fire support. Some are converted into naval ambulances, evacuating wounded personnel from beaches to hospital ships.

| Multimedia |

| Dukw “Swan” Pointe du Hoc |

The Combined Operations Headquarters) has previously experimented with 30-metre power-operated ladders, originally mounted on London fire brigade trucks. For the Normandy landings, a new concept is proposed: mounting a Merryweather Turntable Ladder in the cargo bed of a DUKW amphibious vehicle. This adaptation is codenamed a “Swan.”

To enhance its combat utility, three Browning Automatic Rifles are installed at the top of the ladder. There is also evidence that the three guns mounted are Vickers “K” machine guns. The operational plan is for the Swan to drive ashore, extend its ladder against the cliff face, and allow a Ranger to man the machine guns from the elevated platform. From this position, the Ranger can provide suppressive fire across the cliff-top, clearing German defenders to support the climbing assault force. Meanwhile, Rangers can use the ladder to scale the cliffs.

In total, four of these Swan vehicles are constructed and assigned to the Rangers for the assault on Pointe-du-Hoc. Designated SWAN 1 to 4. Each SWAN is operated by a seven-man Ranger crew. The crews train successfully in landing the vehicles, stabilising them with four jacks, and using engine power to raise the ladder to the top of the cliff. One ladder is assigned to each assault company. The fourth vehicle is held in reserve.

| Multimedia |

| Operational Use |

The DUKW enters frontline service with Allied forces in early 1943. It is deployed simultaneously in both the Pacific and European theatres. Its first combat use occurs during Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943.

By June 1944, the DUKW features prominently in Operation Overlord. During the Normandy landings, approximately 2,000 DUKWs are committed. Over the course of ninety days, these vehicles deliver more than three million tons of supplies ashore. They also transport troops, artillery, and equipment under fire and across beachheads.

The DUKW continues to prove essential in Operation Anvil–Dragoon, the August 1944 landings in southern France. It is used in numerous subsequent operations, including the Battle of the Scheldt and the liberation of Antwerp, Operation Veritable in the Reichswald, and Operation Plunder, the crossing of the Rhine into Germany.

These vehicles become vital in the low-lying, waterlogged terrain of the Netherlands and western Germany. They operate in both flooded and deliberately inundated areas, providing a mobile link between secure supply areas and advancing front-line units.

In the Pacific theatre, the DUKW sees its first use supporting United States Marine Corps operations at Guadalcanal. It is subsequently employed throughout nearly every major island assault campaign, including the battles for the Gilberts, Marshalls, Marianas, and the Philippines.