| Page Created |

| April 6th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| April 26th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Special Forces |

| Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment |

| December 7th, 1942 – December 12th, 1942 |

| Operation Frankton |

| Objectives |

- Attack and destroy docked cargo ships in the port of Bordeaux, France with limpet mines and then escape overland to Spain.

| Operational Area |

Port of Bordeaux, France

| Unit Force |

- Thirteen men of the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment (Captain Hasler, Lieutenant MacKinnon, Marine Sergeant Wallace, Corporals Sheard and Laver and Marines Mills, Ellery, Fisher, Ewart, Conway, Sparks, Moffatt, Colley (reserve))

- Six Cockle Mk. 2 kayaks

- H.M.S. Tuna.

| Opposing Forces |

- German harbour garrison

| Operation Frankton |

The Port of Bordeaux, playing a pivotal role in supporting German war efforts during World War II, serves as a key hub for the shipment of vital resources. Between June 1941 and 1942, this strategic port facilitates the importation of a significant array of essential supplies critical to the Axis powers’ military and industrial operations. Among these are vast quantities of vegetable and animal oils, indispensable for a variety of applications ranging from food production to the manufacture of lubricants and chemicals. Additionally, the port sees the arrival of diverse raw materials, further bolstering the German war machine’s capacity to sustain its extensive military campaigns across Europe.

| May 9th, 1942 |

Lord Selborne, the Minister for Economic Warfare, raises concerns about enemy blockade runners between the Far East and German-occupied European ports, including critical cargoes like rubber, in a letter to Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Following Japan’s entry into the war, maritime traffic between Germany and Japan increases noticeably, significantly threatening to enhance the war efforts of both nations.

| June 22nd, 1942 |

Lord Selborne continues to press the issue, writing again on to Deputy Prime Minister Mr. Attlee, during Mr. Churchill’s trip to Washington. He highlights the projected traffic between Germany and Japan over the next twelve months and its potential impact on their war capabilities.

Further investigations by Lord Selborne’s ministry reveal that Bordeaux is a key port for the enemy’s blockade runners. In the year prior, approximately 25,000 tons of crude rubber had been transported through Bordeaux to Germany and Italy, fulfilling the enemy’s rubber needs. Other vital cargoes include tin, tungsten, and animal and vegetable oils, all crucial for the German war effort. The reverse cargoes to Japan mainly consist of manufacturing equipment and prototypes of various weapons, which are crucial for Japanese military advancements.

The challenge of intercepting blockade runners heading to Bordeaux presents a complex tactical dilemma. Shortly after Lord Selborne, the Minister of Economic Warfare, sent his first letter to Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee both the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force take a look at the problem.

The Navy finds the prospect of a direct naval operation in Bordeaux, deep within enemy-controlled territory, highly impractical and risky. The Royal Air Force, while able to reach Bordeaux by air, faces significant operational limitations. The technology and skills available at the time do not allow for the precise identification and targeting of specific ships within the bustling port. A broad bombing campaign would be necessary, which would entail bombing the entire dock area. Such an action would not only cause substantial collateral damage but also significant civilian casualties among the French populace, many of whom are sympathetic to the Allied cause.

The Foreign Office also expresses reservations about a bombing campaign, concerned about the negative repercussions it would have on public opinion in France. There is a particular worry about the impact on the morale and perception of the Free French forces and supporters abroad. These diplomatic considerations play a crucial role in shaping the operational choices to the British military leadership.

Given the constraints faced in mounting a direct attack, alternative strategies are considered more feasible. The British resort to preventive and harassing tactics, which include deploying submarine patrols in the Atlantic and laying mines at the mouth of the Gironde River by air. These methods aim to disrupt the enemy’s supply lines and impede the movement of blockade runners without the risks and drawbacks associated with larger-scale, direct military actions. The problem is also forwarded to Combined operations Headquarters.

| July 27th, 1942 |

The issues Lord Selborne raises in his June 22nd, 1942, letter about the Bordeaux port is referred to Combined Operations Headquarters, it becomes a significant focal point for strategic planning due to the port’s critical role in German maritime activities. The Examination Committee at Combined Operations Headquarters is charged with exploring possible methods to either destroy the enemy ships harboured there or render the port itself unusable. Bordeaux’s geographical and defensive characteristics pose unique challenges to any direct Allied assault.

Bordeaux is situated approximately eight hundred kilometres from Plymouth, the closest British port of significant size, and requires navigation up the 100-kilometre estuary of the Gironde into the Garonne River. This journey is akin to travelling from Margate to the Tower of London on the Thames, indicating both the distance and navigational complexity involved. Additionally, the natural landscape and the strategic depth of the port within French territory heavily fortify the area, making any maritime approach perilous.

The German military robustly fortifies the approaches to Bordeaux. Naval and air patrols are routinely conducted around the Gironde estuary, while submarines stationed in Bordeaux are dispatched on their missions from this strategic point. Furthermore, coastal defence batteries and anti-aircraft installations cover the potential avenues of approach, significantly enhancing the port’s security against potential Allied attacks.

Recognising the strategic implications and the formidable defences, the Examination Committee deliberates on the feasibility of a direct combined operation. Such an operation, they estimate, would require the deployment of at least three divisions, approximately 50,000 troops, along with a substantial fleet of warships, transports, and extensive air support. Given the ongoing military commitments in the Desert, the Far East, Malta, and the preparations for the landings in French North Africa under General Eisenhower, the resources required for a direct assault on Bordeaux are deemed unavailable. Consequently, the idea of a large-scale combined operation is dismissed. The committee’s response is notably brief and lacks enthusiasm.

Three weeks following this decision, the Search Committee, led by Commander J. H. Unwin, re-examines the situation to explore alternative smaller-scale operations. They conclude that the area is too extensive for an effective bombing campaign, and comprehensive submarine patrolling would demand numerous vessels unless intelligence on ship movements can be significantly improved. Mining the mouth of the Gironde is considered a viable option, as is the potential use of submarines or canoes for more focused missions.

Despite these considerations, no immediate action follows. The complexities involved, combined with the substantial resource allocation needed and the high risks associated with any operation, lead to a cautious approach, reflecting the strategic restraint and prioritization of other theatres of war by Allied planners during this period.

| August 5th, 1942 |

Lord Selborne writes to Mr. Attlee again, emphasising the consistent evidence of Germany and Japan’s determination to maintain their logistics program. He notes that fifteen potential blockade runners are ready at French Atlantic ports, with three en route from the Far East and three more expected to sail soon.

Mr. Attlee passes this correspondence to Brigadier L.C. Hollis, Senior Assistant Secretary of the War Cabinet, instructing him to bring these concerns to the attention of the Chiefs of Staff. The actions after Lord Selborne’s are forwarded to the Chief of Staff, remain unclear.

| September 18th, 1942 |

Major Hasler of the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment, accompanied by Colonel Neville, Royal Marines’ chief planning coordinator, scrutinised potential operations at Combined Operations Headquarters in London, though no suitable plan emerges.

| September 19th, 1942 – September 20th, 1942 |

The decision-making process surrounding the Bordeaux operation is at a critical juncture when Lieutenant-Colonel Cyril Horton who leads a team of Royal Marine planners at Combined Operations Headquarters, is about to declare the mission unfeasible. This perspective is grounded in the array of challenges and resource constraints highlighted by both the Examination and Search Committees at Combined Operations Headquarters. The demands of concurrent military engagements in other theaters add another layer of complexity, making the allocation of substantial resources to a large-scale operation in Bordeaux seem increasingly impractical.

However, the situation takes a significant turn with the arrival of new information conveyed by Colonel Robert Neville regarding Major Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler’s presence in London. Recognising Hasler’s proven expertise in commando operations and innovative military tactics, Horton sees a valuable opportunity to rethink the approach to Bordeaux.

This realisation leads to a swift change in plans. As Major Hasler is about to leave London from Waterloo station, he is urgently recalled.

| September 21st, 1942 |

Major Hasler’s day is consumed by an in-depth review of the Bordeaux File’s specifics, including a thorough examination of navigational charts, assessing “time and distance” factors, and strategizing the optimal insertion point for the raiding force within striking range of Bordeaux.

Hasler’s preparation also requires understanding the enemy dispositions and the geographical intricacies of the Gironde Estuary. Critical natural factors like tidal patterns and lunar phases are also crucial, as the operation needs to be timed during a “dark period” around the new moon to ensure maximum cover for stealth movements. This period coincides with spring tides, which are marked by more extreme water levels and stronger tidal currents, potentially aiding the infiltration and extraction phases of the mission.

Despite incomplete data, Hasler feels confident enough to draft preliminary plans. He spends that evening discussing the feasibility and details with Colonel Robert Neville

| September 22nd, 1942 |

Hasler crystallises his thoughts overnight into what he terms “Outline Proposals,” which he presents that morning. Neville later describes Hasler’s rapid development of these plans as the “quickest outline plan of its kind on record.” His proposal Highlights are:

- Transportation: Hasler proposes using three Cockle Mk II canoes, to be transported by a submarine or another vessel provided by the Admiralty, within 6 kilometres of the Gironde’s mouth under the cover of darkness.

- Attack Strategy: The mission would employ limpet mines to attack enemy ships. The raiding party would paddle from the sea to Bordeaux over four nights, timing the attack to coincide with one of the darkest nights near the new moon.

- Exfiltration: The plan includes a return journey down the estuary over successive nights, with hopes of a rendezvous with the mother ship. If a naval extraction proves impossible, the team is to destroy their equipment and escape overland.

Hasler’s innovative use of canoes is driven by necessity, as more robust vessels like the explosive Boom Patrol Boat are not yet operational. The stealth and flexibility offered by canoes, although physically demanding, provide a significant tactical advantage in terms of silence and non-detection.

The choice of a submarine as the transport vessel, despite its challenges, is strategic. Submarines can approach enemy shores undetected during daylight, allowing precise navigational fixes before launching the canoes after dark. This method, however, requires careful handling to maneuver the canoes through the restrictive torpedo hatches and into the water—a technical challenge Hasler is still addressing.

Major Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler is acutely aware of the challenges his unit faces, given their relatively brief period of training, just two and a half months. Despite their burgeoning capabilities, they are not yet fully prepared for a mission as complex and dangerous as the one planned for Bordeaux. However, Hasler anticipates an additional one to two months to focus specifically on training tailored to the requirements of this particular operation. He recognises the need for discretion and secrecy surrounding the plan, which means that while the operation’s specifics are closely guarded, the intensity of their training can be increased without revealing the mission’s details.

| September 23rd, 1942 – September 27th, 1942 |

During this period of preparation, Hasler was scheduled for a seven-day leave. However, he utilises this time not only for rest and personal activities but also to attend to some professional duties. One day is spent observing parachute tests, an activity likely relevant to his ongoing military interests and perhaps even the upcoming operation. Another day is consumed with administrative tasks, where he finds himself “telephoning madly in all directions,” coordinating and managing aspects of his unit’s preparation from afar.

The remainder of his leave is spent in a more personal and relaxing manner at his mother’s home in Catherington. There, Hasler engages in mundane activities like gardening, which he finds rather tedious, and playing the saxophone, a more enjoyable pastime that provides a mental break from his responsibilities. He also takes the opportunity to simply rest, enjoying the autumn sun—a rare moment of peace in the otherwise intense and demanding life of a military officer.

Throughout this period, Major Hasler maintains a strict protocol of secrecy, a practice he upholds even in the company of his family. His mother, Mrs. Hasler, respects her son’s professional boundaries implicitly. She never probes into the specifics of his work, adhering to a principle of not asking questions about his activities. This mutual understanding allows Hasler to maintain the necessary confidentiality of his military endeavors without the added strain of guarding information from his own family.

The training of the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment escalates in intensity at Southsea, meticulously aligned with Hasler’s plan. Despite the Cockle Mk II’s ongoing development, secrecy envelopes the operation, with only Hasler and Lieutenant Jock Stewart, his second-in-command, privy to the details. The men remain uninformed of their mission until their departure.

| September 28th, 1942 |

In the weeks following his leave, Major Herbert Hasler’s preparations for Operation Frankton enter a phase of heightened activity and urgency. Recognizing the need for tight security and effective collaboration, Hasler brings only one confidant into the full depth of planning: Jock Stewart. Together, they embark on a rigorous schedule, sometimes extending their working hours late into the night, occasionally relying on benzedrine to sustain their alertness and energy.

The preparations involve extensive modifications to the canoes, the Cockle MK II, intended for the mission, reflecting the unique challenges posed by the operation’s requirements. This period also requires meticulous attention to the assortment of necessary supplies, including specialized stores, food, and clothing adapted for the arduous task ahead. Alongside these physical preparations, Hasler is also tasked with refining the operational plan for Frankton, which requires iterative revisions and approvals from higher military authorities.

Hasler’s efforts to secure the necessary assets for the mission lead him to Captain S. M. Raw, the chief staff officer to the Admiral, at Northway in London. His discussions are fruitful, culminating in the authorization to use a submarine for the insertion of the raiding party. However, this approval comes with the understanding that the submarine, which would be part of the 3rd Submarine Flotilla based out of Holy Loch on the Clyde, will not be able to return for extraction. The risks of such a maneuver, particularly in the wake of the anticipated explosions and enemy alertness, are deemed too great. This situation effectively leaves the raiders with no naval extraction possibility, confronting them with the daunting prospect of an overland escape through enemy, occupied territory, a perilous journey that will test their endurance and evasion skills to the utmost.

To maintain operational secrecy and provide plausible cover for the sudden relocation of his unit, Hasler cleverly frames the move to the Clyde as a routine transfer for “advanced training.” This half-truth serves both as a believable reason for the unit’s departure from their usual bases and as a strategic misdirection from their actual mission objectives.

As the details of Operation Frankton are meticulously planned, Major Hasler finds himself deeply involved in every aspect of the preparations. The failure of the Dieppe raid earlier in August underscores the necessity for detailed and thorough planning. Hasler’s collaboration with Lieutenant-Commander G.P. L’Estrange, a staff officer at Combined Operations Headquarters, proves crucial. L’Estrange provides invaluable assistance by compiling detailed information on the tides, currents, enemy dispositions, and local topography of the Gironde area. In preparation for the mission, L’Estrange meticulously prepares reference cards for each canoe, which include all essential navigational and environmental data.

| October 12th, 1942 |

Major Hasler and Lieutenant-Commander L’Estrange visit Captain S.M. Raw to finalise details concerning the submarine that will deploy the canoes.

| October 18th, 1942 |

The plans are further refined on when they draft the first revised outline for the operation, still planning to utilize only three canoes.

| October 13th, 1942 |

The full plans for Operation Frankton are officially presented and approved by Admiral Louis Mountbatten. However, he makes significant amendments to the initial proposal by expanding the number of kayaks involved from three to six. This expansion aims to increase the operational impact and ensure redundancy if any team encounters difficulties. The personnel selected for the raid are organised into two divisions, each tasked with distinct targets in the Bordeaux area, a critical axis for German maritime logistics.

Composition of the Teams:

A Division:

- Catfish: Major Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler and Marine Bill Sparks

- Crayfish: Corporal Albert Laver and Marine William Mills

- Conger: Corporal George Sheard and Marine David Moffatt

B Division:

- Cuttlefish: Lieutenant John Mackinnon and Marine James Conway

- Coalfish: Sergeant Samuel Wallace and Marine Robert Ewart

- Cachalot: Marine W.A. Ellery and Marine E. Fisher

Additionally, Marine Norman Colley is included as a reserve, providing support and additional manpower if needed during the operation.

Despite the well-organised structure and the strategic planning behind Operation Frankton, a significant leadership issue emerges. Major Hasler, originally slated to lead the mission, is informed by Lord Mountbatten that he will not be participating directly in the raid. Mountbatten’s decision stems from concerns over the high risk associated with the operation and the desire to preserve Hasler’s expertise for future operations. This decision is influenced by the strategic value Hasler holds as a specialist in raiding operations and his critical role in developing new tactics for Combined Operations.

Distressed by the notion of not accompanying his men on such a dangerous mission, Hasler argues that his leadership and navigational expertise are vital for the success of the operation. He contends that the practical experience he would gain and impart during the operation is indispensable and that his absence could demoralize his unit and potentially jeopardize the mission’s success.

In response to Mountbatten’s decision, Hasler drafts a memorandum to Cyril Horton, passionately making the case for his participation. He highlights the operation’s significance and his unique qualifications, drawing a parallel to Major Stirling’s role in leading similar high-risk operations in North Africa. Hasler’s argument emphasises that effective leadership in such critical and dangerous missions often hinges on the presence of experienced and skilled commanders who can inspire and lead by example.

| October 20th, 1942 |

Enhanced preparation for the raid start, encompassing kayak handling, submarine embarkation and disembarkation, limpet mine management, and escape and evasion tactics. The Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment conducts a mock attack on Deptford from Margate, kayaking up the Swale as part of their training.

For the operation, they select the Mark II kayak, codenamed “Cockle” These semi-rigid, two-person kayaks feature canvas sides, flat bottoms, and are 4.6 metres long, designed to be collapsible for storage inside a submarine. Each kayak carries a comprehensive load for the raid, including two crew members, eight limpet mines, navigational and survival gear, and weapons, with a total carrying capacity of 220 kilograms.

The personnel also carry a .45 1911 Colt semi-automatic pistols and Fairbairn–Sykes fighting knives, preparing them for both the demolition objectives and potential close-quarters combat situations.

| October 29th, 1942 |

During a meeting at Combined Operations Headquarters chaired by Lord Mountbatten, the plan and Hasler’s role are again thoroughly discussed. Despite initial resistance from other senior officers, Mountbatten ultimately grants Hasler permission to lead the raid, acknowledging his passion and the potential impact on morale and effectiveness if he were excluded.

Mountbatten’s approval is a significant morale booster for Hasler, reinforcing his commitment and dedication to the operation. This decision not only reflects the high stakes of Operation Frankton but also highlights the complexities of wartime leadership and the balance between strategic caution and the operational need for experienced, hands-on leadership. Upon receiving Lord Mountbatten’s approval to lead Operation Frankton, Major Hasler is elated and immediately travels to Glasgow to continue preparations.

| October 30th, 1942 |

Admiral Mountbatten forwards the operation’s ‘Summary of the Outline Plan’ to the Chiefs of Staff Committee.

Meanwhile, Hasler arrives in Glasgow. He finds the H.M.S. Forth, the submarine depot ship, anchored in Holy Loch, alongside several of her brood. He is having a highly productive meeting with Captain Ionides, the commander of the 3rd Submarine Flotilla who proves to be exceptionally prompt in assisting him with his numerous challenges.

| October 31st, 1942 |

No. 1 Section of the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment arrives in Holy Loch. Captain Stewart arrives as well. Storeman Drew and Marine Todd join too, serving as Marine Operations Assistants to the officers. Once they also take their quarters aboard H.M.S. Forth, they start working on their program towards the operation. Major Hasler quickly meets them at Gourock and promptly escorts them away. Their upgraded Mk II Cockles, equipped with all the latest enhancements, are also delivered.

| November 1st, 1942 |

The men take the canoes out for their inaugural training on limpet mine attacks. The submarine Tuna, initially designated for their drills, is regrettably unavailable, but Captain Ionides makes arrangements for them to use P339 and P223 for their trials and training in hoisting-out techniques. They begin their exercises using the davits of the Dutch minesweeper Hr. Ms. Jan van Gelder to address any initial difficulties. This ship also serves as the target for their practice limpet attacks.

To replicate the tidal conditions of the Gironde Estuary, the Jan van Gelder maintains a speed of about one knot. This setup allows the team to practice manoeuvring the canoes and deploying their mines while mastering the technique of securing themselves with magnetic holdfasts and placing the limpet mines six feet below the waterline, ensuring each man is proficient in these critical tasks.

| November 3rd, 1942 |

The Chiefs of Staff Committee formally approves the plan, setting the stage for the next steps in the operation’s execution.

Recognizing the inherent risks associated with such a daring mission, Mountbatten prudently decides to increase the number of kayaks, referred to as “Cockles,” from the original three to six. This decision is aimed at providing redundancy and enhancing the operation’s chances of success, acknowledging the potential for accidents or losses during such complex and hazardous undertakings.

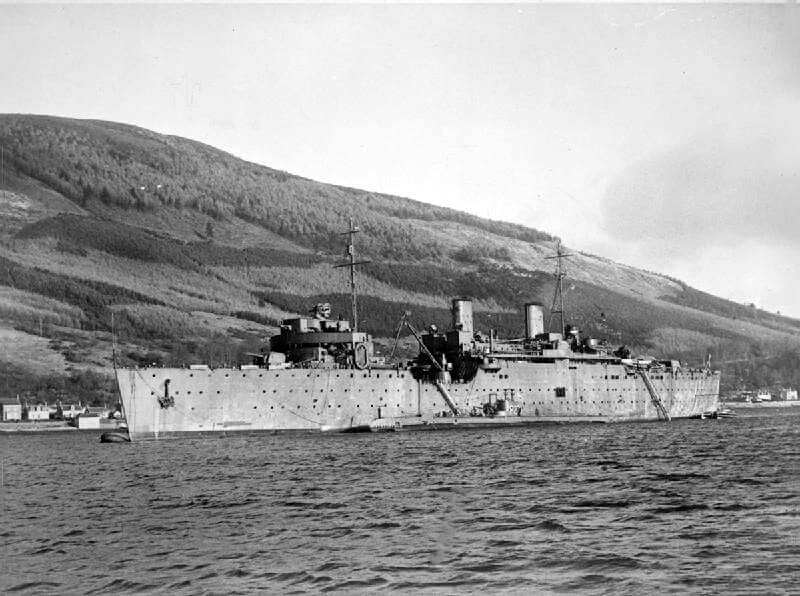

Submarine and Training Details: The submarine H.M.S. Tuna, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander R.P. Raikes DSO, Royal Navy, is assigned to the mission. The H.M.S. Tuna is part of the 3rd Submarine Flotilla, led by Captain H.M.C. Ionides. Training for the raid is conducted under Captain Ionides’ supervision, emphasizing that the operation will only proceed if the training standards are satisfactorily met, ensuring the preparedness and competency of all involved.

Operational Parameters: The Tuna is scheduled to depart around November 30th, 1942 for a patrol in the vicinity of the Gironde Estuary, where the raid is to take place. Part of its mission includes potentially engaging enemy ships encountered during its patrol. However, if such engagements compromise the safety or secrecy of Operation Frankton, the operation is to be aborted, highlighting the precarious balance between conducting standard naval operations and executing special raids.

The final decision on how many kayaks can be accommodated aboard the H.M.S. Tuna is left to the discretion of its commander, Lieutenant-Commander Raikes, after consultation with Major Hasler. This flexibility allows for adjustments based on practical assessments of the submarine’s capacity and the operational requirements, ensuring that the mission is tailored to the realities of the situation.

Meanwhile, the Section 1 teams undertake a rigorous practice session, paddling the fully loaded canoes for a grueling six and a half hours. This exercise tested their endurance and cohesion as a unit, leaving them ‘very exhausted’ but more prepared for the operational challenges ahead.

Following this demanding physical trial, all ranks have their first practical experience aboard the submarine P339, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Wingfield. This phase includes practice in hoisting out the canoes during adverse weather conditions, a heavy squall, in particular, and participating in diving and action trials. These submarine-based drills are critical, as they provide the teams with vital familiarity with the submarine operations that would be instrumental in the actual mission.

| November 7th, 1942 |

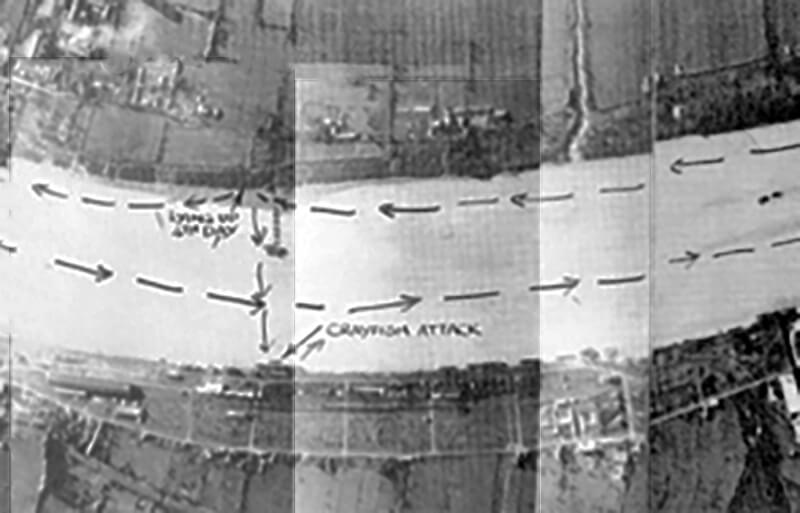

The rehearsal for an operation, codenamed Blanket, was designed to simulate the conditions of the Gironde Estuary in France, utilising the Thames River in Britain due to its similar distance and navigational challenges. This exercise aimed to prepare the crews for a 115 kilometres paddle from Margate to Deptford, closely overseen by the Commander-in-Chief, Nore Command, who ensured all coastal defences were alerted and ready to challenge the participants using a designated code-word.

Lieutenant Hasler and Stewart depart Glasgow. They make strategic stops to consult with military leadership in London and Chatham, and then proceed to Margate where they brief the crews and meticulously prepare tide tables up until midnight. The exercise would commence the following night under seemingly ideal conditions with misty weather and a flat calm sea.

| November 9th, 1942 – November 14th, 1942 |

Start of Exercise Blanket. Navigation proves disastrous from the outset. Mackinnon, navigating independently from the Swale, becomes disoriented in the fog, running aground amid mudflats. The confusion worsens due to the P8 grid compass’s design, which could easily be misread by 180 degrees.

Corporal Sheard fares even worse, losing formation completely and ending up kilometres outside the designated exercise area. His misadventure begins when he mistook a seagull for Hasler’s canoe and follows it, leading him in the opposite direction of the intended course.

Exhausted and demoralised, the teams arrive at Blackwall five nights later, significantly short of their target at Deptford. Throughout the exercise, every canoe is spotted and challenged at least twice, highlighting the difficulties in maintaining stealth. Additionally, the physical demands of the exercise take a toll on the crews, who struggled to cope with the strain.

| November 15th, 1942 |

Major Hasler attends a debriefing at Combined Operations Headquarters to analyse what had gone wrong during Exercise Blanket. This session, known as a post-mortem, is crucial for understanding the flaws in execution and preparation.

Feeling much depressed about the outcome, Hasler is in the all-ranks canteen for lunch, a facility implemented by Lord Louis Mountbatten to foster a sense of camaraderie and unity within Combined Operations Headquarters. While Hasler is having a beer and sandwich, Mountbatten approaches him, already aware of the exercise’s poor results. His inquiry about the rehearsal isn’t just perfunctory; it is an opportunity to gauge Hasler’s reaction and mindset following the setback.

Hasler admits to Mountbatten that the rehearsal was a “complete failure.” In response, Mountbatten, with his characteristic optimism, offers a silver lining, suggesting that the failure is beneficial. He smiles and remarks, “Splendid! In that case, you must have learnt a great deal, and you’ll be able to avoid making the same mistakes on the operation.”

| November 17th, 1942 |

Major Hasler and Captain Mackinnon spend the day at the Special Operations Executive development centre known as Station IX (formerly known as the Inter-Services Research Bureau) at Welwyn, to talk about time delay capsules for the Limpet Mines

| November 18th, 1942 |

Major Hasler and Captain Mackinnon return to London for a critical assignment, attending a special briefing at a confidential department within the War Office. Here, they engage with experts in espionage and covert operations, receiving training in the No. 3 Code, a secretive communication method designed for soldiers captured by the enemy to send simple, yet crucial messages back to Military Intelligence.

| November 19th, 1942 |

Major Hasler and Captain Mackinnon return to the Clyde, only to discover that the cabin accommodations aboard H.M.S. Forth are fully occupied. Consequently, the entire detachment is housed on a “hotel ship” named the Al Rawdah, moored nearby.

To ensure peak physical and operational readiness, Hasler and his team engage in rigorous training activities. They undertake forced marches across the hills of Bute, integrating practice with pistols and the silent Sten gun, emphasising stealth and precision. Their combat training also includes the use of the fighting knife, following the Fairbairn system commonly taught in Commando units.

Following the problems during Exercise Blanket, navigational skills are a critical focus of their preparation. The team conducts extensive navigational exercises both during the day and at night to hone their ability to move and operate under various conditions. Special emphasis is placed on mastering the use of the limpet mine. They practice its tactical deployment against a mock target, the Hr. Ms. Jan van Gelder, and repeatedly drill the fusing process. This fusing becomes a standardised drill performed at the command, ensuring each man can execute it flawlessly even in complete darkness.

Additionally, compass work receives particular attention. With the assistance of the Navigating Officer from H.M.S. Forth, the team diligently works to perfect their navigational accuracy. All canoes, fully loaded with operational equipment, are “swung”, a process to determine compass deviation. Any detected errors are corrected using the compass corrector mounted underneath each canoe, minimizing potential navigational discrepancies during their mission.

This intensive period of training and preparation is critical, equipping Hasler and his team with the skills and tools necessary for the precise execution of their upcoming operation. Their readiness is not only about physical fitness and combat skills alone but also about ensuring technical proficiency with their equipment and flawless navigation under any circumstances.

| November 29th, 1942 |

During the afternoon Major Hasler gathers Number One Section of his Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment. He orders them to pack their gear and the six Cockle Mk II canoes for an imminent departure and advises them to spend the evening writing letters home.

| November 30th, 1942 |

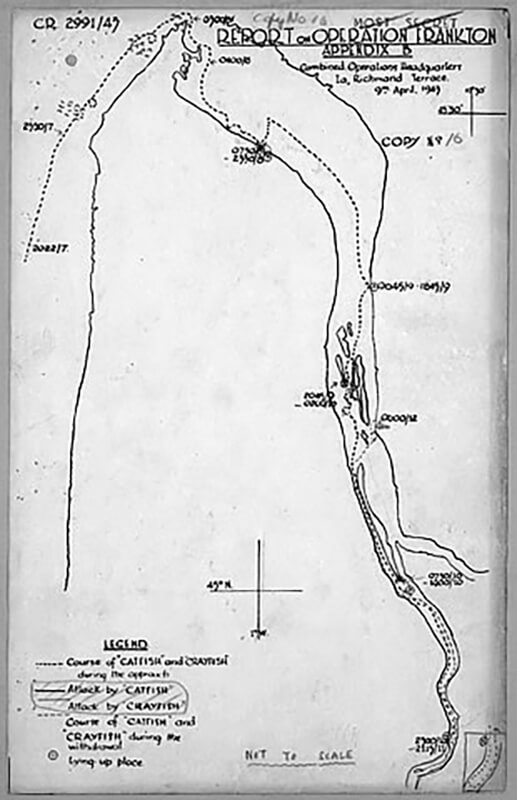

Major and No. 1 Section board the submarine Tuna, embarking on a critical covert mission. The intricate process begins with carefully loading the collapsible canoes and essential supplies through the submarine’s forward torpedo hatch. L’Estrange and Jock Stewart, privy to the mission’s details, offer quiet farewells and good luck as the Tuna departs from HMS Forth, with the Marines saluting their depot ship in a solemn ceremony that underscores the gravity of their undertaking.

Once underway, Hasler gathers his men in the forward torpedo space, surrounded by the stowed canoes and gear, to finally disclose the mission’s nature. He explains that they are to execute a real operation against the enemy, targeting the Gironde Estuary near Bordeaux. The plan involves a night-time drop 10 miles south of Pointe de Grave, navigating strong tidal currents, and using the cover of darkness to approach and sabotage enemy ships in Bordeaux with limpet mines.

Major Hasler has assigned specific target areas along the Gironde Estuary to different divisions of his team, organising them based on their operational roles and areas of expertise. Here is how the assignments are distributed:

- Bordeaux, West Bank:

- ‘A’ Division: Catfish, led by Major Hasler and Marine Sparks. This division is tasked with strategic points on the western bank of Bordeaux, leveraging Major Hasler’s extensive experience and leadership.

- ‘B’ Division: Cuttlefish, commanded by Lieutenant Mackinnon and Marine Conway. They are assigned to support and extend the operations initiated by ‘A’ Division on the west bank, ensuring comprehensive coverage and backup.

- Bordeaux, East Bank:

- ‘A’ Division: Crayfish, with Corporal Laver and Marine Mills. This team focuses on the eastern sectors of Bordeaux, targeting critical points to maximize the disruption of enemy activities.

- ‘B’ Division: Coalfish, led by Sergeant Wallace and Marine Ewart, complements the efforts on the east bank by covering additional strategic locations, ensuring a synchronized assault across the river.

- Bassens, North and South Quays:

- ‘A’ Division: Conger, under the guidance of Corporal Sheard and Marine Moffat. This division is responsible for the north and south quays of Bassens, a key logistical area for enemy supplies and reinforcements.

- ‘B’ Division: Cachalot, which includes Marine Ellery and Marine Fisher, is tasked with assisting Conger by covering alternate targets in the area, enhancing the impact on the enemy’s operational capabilities.

The operation is meticulously timed to coincide with the second week of December’s dark period for optimal stealth.

Hasler outlines the German defences they will face, including armed patrols and heavy artillery on land, and stresses the importance of stealth, careful navigation, and the strategic placement of limpets on target ships. The raiders are instructed on the specifics of navigation, enemy engagement avoidance, and the procedure for the eventual scuttling of their canoes and overland escape through Spain, emphasizing the operation’s high risk and the improbability of external extraction.

The briefing concludes with a detailed discussion on emergency protocols, interaction with locals, and a secret communication method to be used if captured. Despite the daunting nature of the mission, Hasler’s thorough preparation and transparent briefing bolster the morale of his men, who are eager to execute the plan and trust in Hasler’s leadership. The atmosphere is tense yet charged with a resolute spirit, as the men prepare to face one of their most challenging operations.

| December 1st, 1942 – December 5th, 1942 |

During the first night, Lieutenant Hasler and his team aboard the submarine Tuna successfully conduct their final rehearsal for hoisting the canoes out, completing the task in a swift 31 minutes. This marks the start of a week filled with intense preparations as the submarine navigates towards the mission zone.

Throughout the week, Hasler continuously reviews the operational plans with his team, ensuring every member can operate independently if necessary. They practice the No. 3 Code, meant for communication if captured, and attempt to learn basic French phrases, although many find this challenging and consider relying on sign language instead.

The team carefully studies air photos and new intelligence to familiarize themselves with the terrain and identify potential hiding spots along the Gironde Estuary. Mackinnon, particularly motivated, lectures on the expected coastal features at their hiding spots. All equipment and escape gear are thoroughly inspected and repacked, with Hasler explaining their use in detail.

As Tuna travels through the Irish Sea and the Bristol Channel, the rough conditions cause seasickness among the crew. To avoid enemy detection, Tuna submerges during the day and only surfaces at night. The cramped conditions and limited sanitation aboard the submarine lead to discomfort and claustrophobia, complicating the crew’s adjustment to life underwater.

Despite these challenges, the marines’ morale gradually improves. They are intrigued by the operation of the submarine and the leadership of Captain Dick Raikes. Raikes manages the crew with calm and precision, maintaining discipline and efficiency. His methodical approach and the strict environment aboard Tuna help ensure that all operations are conducted smoothly.

This intense preparation period is critical for ensuring that each team member is ready and focused for the mission. As they approach their target, the crew is not only prepared operationally but also mentally for the challenges ahead. The rigorous planning and the difficult conditions they endure aim to prepare a resilient team capable of executing a challenging raid against tough opposition.

| December 6th, 1942 |

As the H.M.S. Tuna nears the French coast, it submerges for the approach, surfacing only briefly around midday. Below deck, Major Hasler’s marines ready themselves for disembarkation, buoyed by the calm sea conditions and light-hearted banter among themselves.

However, precision is crucial for the success of the mission. The submarine’s captain, Raikes, is adamant about accurately determining their location to ensure that Hasler can effectively navigate towards Pte de Grave and into the Gironde Estuary. Raikes stresses the importance of this precision, expressing concern about a nearby minefield laid by the Royal Air Force, which has unreliable charting. He plans to use his periscope to take multiple bearings of coastal points to fix their position accurately.

Unfortunately, Captain Raikes faces significant challenges due to mist that morning, which prevents him from obtaining an “astro-fix” — a necessary series of star readings that would have provided a precise location. This astro-fix is crucial for identifying specific coastal features in the afternoon. Additionally, the presence of French fishing boats complicates matters further. These boats, potentially carrying German observers with radios, pose a threat to the submarine’s stealth approach. Raikes has to frequently raise and lower the periscope, which could easily be spotted by fishermen in the calm sea conditions.

By late afternoon, after several attempts to secure a reliable position fix without success, Captain Raikes makes the decision to delay the mission. He communicates to Major Hasler that they cannot safely proceed towards the minefield without a more accurate fix. Disheartened, Major Hasler relays the news to his marines, who are already geared up for action. While there is an initial disappointment, morale is quickly bolstered by humor, as one marine jokes about enjoying a proper breakfast the following morning instead of the usual composite rations. They then repack their gear, preparing to wait for another day.

| December 7th, 1942 |

The following day, under continued calm conditions, the H.M.S. Tuna obtains a satisfactory astro-fix before dawn, allowing Captain Raikes to use the periscope for close shore navigation despite high enemy air activity. Captain Raikes painstakingly takes coastal bearings, maneuvering northward under the risk from both the minefield and enemy aircraft until spotting the Cordouan lighthouse—confirming their position.

At 13:45, Captain Raikes informs Major Hasler they have a solid fix near the planned disembarkation point, despite the proximity to the troubling minefield and a German radar station. This update revives spirits, setting the stage for the night’s operation, pending avoidance of patrolling enemy boats.

As night falls, the marines assemble their gear and prepare the canoes with precision. Despite a clear night increasing the risk of detection, the crew is ready by 19:30, and the submarine surfaces. Captain Raikes and the lookout crew, pre-adapted to the dark, keep vigilant for enemy patrols. A German trawler is spotted but deemed a safe distance away.

The deck crew efficiently launches the canoes. However, during the deployment of the canoes from the H.M.S. Tuna, an incident occurrs with one of the canoes, the Cachalot. As it is being hoisted through the torpedo hatch, the canoe snags on a sharp edge of the hatch clamp, resulting in a significant tear in its canvas side. Marine Ellery, responsible for the Cachalot, immediately notices the damage and calls over Major Hasler to inspect the canoe.

Upon reviewing the damage, Hasler quickly determines that the tear was too severe for the canoe to be safely used in the operation. He decisively instructs Ellery to lower the Cachalot back into the submarine, effectively removing it from the mission. This decision visibly affected Marine Ellery, who appears disappointed by the outcome. The situation also deeply impacted Fisher, Ellery’s No. 2. Known for his resolve despite not being able to swim, Fisher is emotionally overwhelmed by the sudden cancellation of their participation.

Despite this setback, the rest of No. 1 Section is hoisted successfully into the Bay of Biscay, under the cover of darkness and amidst the distant glow of searchlights and the chill of the open sea.

By 20:22, all operational canoes are in the water, maneuvering into formation, ready to execute their mission. and the crew of the H.M.S. Tuna bids farewell to the marines.

During the evening, the operation’s setting is marked by a tense yet quiet atmosphere as the five cockle canoes navigate the Biscay sea. The calm is occasionally broken by the sounds of paddles stirring the water. The crews are alert and determined, following a course designed to navigate between Pte de Grave and the island of Cordouan. Early on, Major Hasler discovers a significant error in his compass but manages to correct it using the North Star for guidance. The night’s challenges include managing a slight leak in Hasler’s canoe and contending with the cold, which is exacerbated by the seawater spray.

As they progress, the marines have to adjust their route slightly eastward to align with the coastal contours. The quiet of the night is soon interrupted by the alarming sound of roaring water ahead, signaling the approach of a tide race—a sudden rush of strong tidal flow across a sandbank or through a narrow channel, which can be perilous for small vessels like their canoes.

Hasler, drawing on his experience with similar conditions at Start Point and St Alban’s Head, quickly gathers the crews to explain the situation. He instructs them to apply their rough-water training, which involves tightening cockpit covers and maneuvering head-on into the tide race. The teams brace themselves and successfully navigate through the turbulent waters, though not without significant effort and risk.

Unfortunately, during this first encounter with the tide race, Sergeant Wallace and Marine Ewart in the Coalfish are lost from sight and do not rejoin the group. Despite efforts to locate them, including using a seagull call signal, there is no response, and the harsh conditions and swift tide make it impossible to conduct a thorough search.

| December 8th, 1942 |

Regrouping after the ordeal, the remaining canoes continue towards their objective, only to face another tide race. This second encounter is even more intense, with waves reaching heights that severely test their endurance and skill. Amidst the chaos, the Conger capsizes, throwing Corporal Sheard and Marine Moffat into the icy waters. Though they manage to cling to their canoe, the situation is dire.

Hasler makes the tough decision to abandon the swamped Conger to avoid compromising the entire mission. Sheard and Moffat are instructed to attempt an escape ashore, highlighting the brutal realities of such covert operations where difficult decisions must be made for the greater good of the mission.

As they approach the lighthouse at Pte de Grave, which unexpectedly turns on, illuminating the area and potentially exposing them to enemy observation and the men come upon three German frigates. Lying flat on the canoes and paddling silently they manage to get by without being discovered.

Once cleared, the marines face yet another tide race. This third challenge proves just as daunting, with all members struggling to maintain control and cohesion. During this tumultuous crossing, the team from Cuttlefish, led by Lieutenant Mackinnon and Marine Conway, faces extreme difficulties. The powerful currents and challenging navigation conditions prove too much, and the Cuttlefish is last seen struggling to maintain course. The fate of its crew becomes uncertain to the remaining members of the operation adding to the operation’s toll. Hoping they would continue their mission on their own the team contnues their journey.

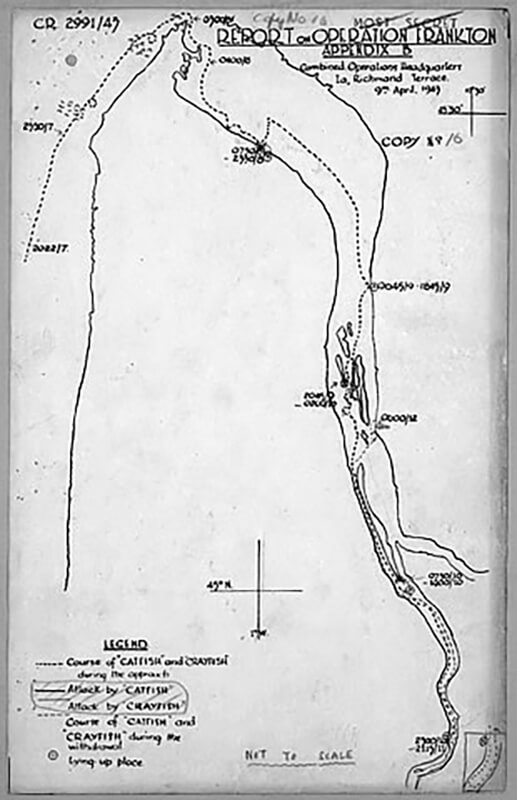

Exhausted, cold, and significantly reduced in number, the remaining teams manage to navigate past the hazards and make their way into the estuary as dawn approaches. They start seeking for a hiding place to rest. On the first night the two remaining crews covered over forty kilometres in 11 hours and land near Pointe aux Oiseaux around 07:45. While they are hiding during the day and unknown to the others, Sergeant Wallace and Marine Ewart in Coalfish are captured at daybreak beside the Pointe de Grave lighthouse where they came ashore.

As Major Hasler and his group are hiding, they observe local fishermen and their families starting their day by the river. After taking shifts for a brief rest and consuming compact rations, Hasler and his team remain alert, aware that they have been seen by the locals. Hasler decides to reveal their identity to ensure the fishermen’s silence, hoping it decreases the risk of betrayal. The Frenchmen, likely frightened and preferring to avoid trouble, give no guarantees but offer some food before departing.

The team is exhausted, enduring harsh conditions without adequate sleep or shelter. They stay vigilant, fearing the Germans might be alerted to their presence due to missing comrades or radar detection of their submarine, Tuna. They brace for potential confrontations but are relieved when a perceived threat turns out to be mere stakes on a dyke. Around 23:30 the men put their canoes back in the water. Getting the boats clear of the shore in the dark is challenging due to large areas of outlying sandbanks beyond the low-water mark. The Atlantic swell breaks into small fast rollers over these sandbanks, which the canoes must confront head-on. Skillfully, Hasler navigates through these obstacles into the open channel. Navigation becomes straightforward as the port-hand buoys of the shipping channel flash blue lights, guiding them. They maintain a distance of about two hundred yards from the channel to avoid any shipping. The weather remains flat calm and cloudless.

| December 9th, 1942 |

Hasler sets a vigorous pace, braving extremely cold conditions. The spray freezing on the cockpit covers and ice forming on their gloves from the dripping paddles add to their challenge. The occasional benzedrine tablet helps them push through the cold, and during hourly rests, they exchange jokes and discuss their progress and plans.

One tense moment occurs when they must cross the shipping channel and narrowly avoid a convoy of large ships, an encounter that highlights the potential dangers of their journey but also underscores the strategic importance of their mission.

After six hours of strenuous paddling covering again a little over 40 kilometres, they reach the east bank of the estuary north of Portes de Calonge, continuing some 1.5 kilometres offshore until dawn approaches. Hasler, utilising his exceptional night vision, locates an almost perfect hiding spot around 07:30 between two hedges by a field, allowing them a much-needed rest in a dry ditch.

Despite a day of relative quiet, the presence of a low-flying German plane and the activity of local cows near their hideout keep them alert. They manage to rest intermittently, with the constant buzz of aircraft overhead reminding them of the ever-present danger.

Major Hasler holds onto hope for the canoe teams of Wallace and particularly Mackinnon, believing they might still be actively pursuing their objectives independently, though he harbors concerns about their potential capture.

Preparing for the third night, Major Hasler faces the challenge of timing. They need to start early due to limited hours of favorable tides but must also navigate through a complex area with many islands and varying tidal conditions. The plan involves making the most of three initial hours of flood tide, followed by six hours of ebb during which they must secure another night hide, before another three hours of flood tide before dawn. They aim for a location optimistically named “Desert Island.”

As twilight falls, the calm weather continues, offering too much visibility for comfort. The raiders, stiff and cold from their hiding spot, eagerly prepare for the physical exertion of the night. They carry their canoes to the river. As the team prepares to launch, their movement catches the attention of a local Frenchman from a nearby farm, who approaches curiously. Unlike the reserved fishermen they encountered earlier, this man is openly friendly, offering them a drink at his house. Hasler, wary but polite, declines the invitation, maintaining their cover by thanking the Frenchman and assuring him they need to proceed. The farmer, though disappointed, respects their decision, promising to keep their presence a secret and wishing them luck as they set off into the increasingly dark waters.

Their night’s journey begins with a mix of relief and tension, grateful for the farmer’s friendliness yet burdened by the knowledge that they have been seen. This visibility underscores the constant risk they face, even in seemingly safe moments, as they paddle onward under the cover of darkness. Around 18:45 they resume their way towards their objective.

The raiders progress well initially but must navigate closely to the shores of an archipelago, heightening their anxiety due to the noticeable sound of dripping paddles. It’s still early evening, and the normal activities on shore make stealth difficult. As they approach the first island, the sudden start of a motorboat nearby alarms them. They quickly hide among tall reeds, observing the motor-launch pass without lights, suspecting it might be a patrol boat.

Eventually, they continue and arrive at Desert Island, located directly opposite the St Julien vineyards. Here, the ebbing tide impedes their progress, forcing them to confront the daunting banks of the island, thick with tall, dense reeds and slippery mud. After several attempts, at 20:45, they manage to find an opening to drag their canoes ashore and secure a brief rest.

Meanwhile, in Great Britain, Cyril Horton at the Combined Operations Headquarters in London receives a brief but significant update. The message from H.M.S. Tuna, coded as “Operation Frankton completed 2100/7”, confirms that the submarines have successfully launched the cockle canoes, and Major Hasler and his team have commenced the most dangerous phase of their mission.

Later that evening, driven by a mix of concern and duty, Horton steps out into Whitehall to gather more information and buys an evening newspaper. Turning to the Stop Press section, he encounters a disheartening report. The paper features an announcement from the German High Command stating that on December 8, a small British sabotage squad has been engaged at the mouth of the Gironde River and has been “finished off in combat.”

This news strikes Horton with a heavy blow. The terse message from the Germans suggests a grim outcome for Hasler and his team, indicating that their mission has been compromised and possibly that they have been intercepted and neutralised by German forces. Horton’s heart sinks as he processes the implications of this report, reflecting the precarious nature of such covert operations and the constant risk faced by those involved.

At Southsea, Sergeant King, upon noticing the German High Command announcement, brings it immediately to the attention of Jock Stewart, who is temporarily in command of the unit. Understanding the potential for panic and the spread of demoralisation among the troops, Stewart takes a decisive step to maintain control and focus within his team. He issues a strict directive that the matter is not to be discussed among the unit members. By restricting discussion on the topic, he seeks to protect his troops from unnecessary worry and keep them concentrated on their immediate duties and responsibilities.

| December 10th, 1942 |

By 02:00 the four remaining raiders awake to continue their journey, only to find the tide still receding, delaying their departure. Launching the canoes proves exceptionally challenging as they must first navigate a 1.8 metres mud cliff and a stretch of muddy beach. The men, covered in mud and thoroughly chilled by the cold, work noisily to move their canoes to the water’s edge, concerned that their efforts might alert nearby residents.

The team successfully crosses the shipping channel and maneuvers through a perilous stretch between the west bank and Ile Verte with extreme caution, hugging the island’s reed-thick shores. By 06:30, as they approach Ile de Cazeau’s southern end, the urgency to find a hideaway intensifies with the onset of daylight.

Clinging to the island’s dense foliage for cover, they encounter a small pier indicating human activity, but opt to investigate due to the dense woods beyond. Hasler’s quick reconnaissance reveals a military installation, likely an anti-aircraft position, confirming the strategic importance of their location.

With morning breaking and visibility increasing, Hasler leads a quiet retreat from the potential danger zone. They press on to the island’s narrow tip, where the pressure of imminent daybreak forces a hasty decision. At the last possible moment around 07:30, they conceal themselves in a field of long marsh grass, camouflaging their presence as the sounds of the waking mainland fill the air. They remain hidden, hoping their cover remains secure as the day progresses.

During their most stressful day in a hide, the men find themselves trapped and unable to move, sleep, cook, smoke, or relieve themselves comfortably. They remain caked in mud from the previous night’s exertions, and a persistent, thin rain adds to their discomfort. The proximity of a German gun site, separated only by a sparse line of trees, heightens their anxiety.

Throughout the day, the presence of cattle and low-flying reconnaissance aircraft intensifies their sense of vulnerability. The cattle, curious about the strange new objects in their field, encircle the camouflaged boats, while the aircraft scrutinize the area from above. Despite these challenges, the marines maintain their discipline, remaining motionless and silent, which effectively conceals their presence. Physically and mentally strained by their efforts, the team feels the harsh effects of exposure. Their wet clothing freezes, making every movement a crackling effort, reminiscent of a starched shirt, as they endure the harsh conditions.

As they move further from the Gironde into the Garonne, Bordeaux and the target ships are only about twelve miles upstream. Initially, Major Hasler plans to launch an attack on these enemy vessels on the night of December 10th, 1942. However, they haven’t progressed far enough up the river to ensure a safe retreat after the attack. Given this, and after reviewing his charts and air photos, Hasler opts to move a shorter distance that night to establish an advanced base. This position places them within a manageable range for striking at the enemy and subsequently withdrawing effectively.

Despite feeling unrested and having endured a particularly uncomfortable and perilous day, the group is eager to leave their precarious position. Unknown to four raiders, the Cuttlefish canoe team of Mackinnon and Conway is also on the same island, only a few kilometres away. That evening, at 18:45, they relaunch their canoes. They face the same challenging conditions as before, dealing with the steep, slippery mud banks that make entry into the water difficult.

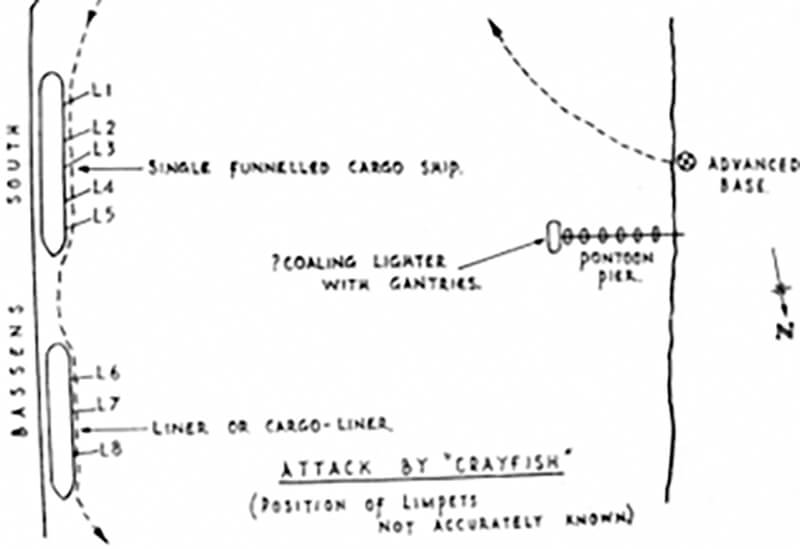

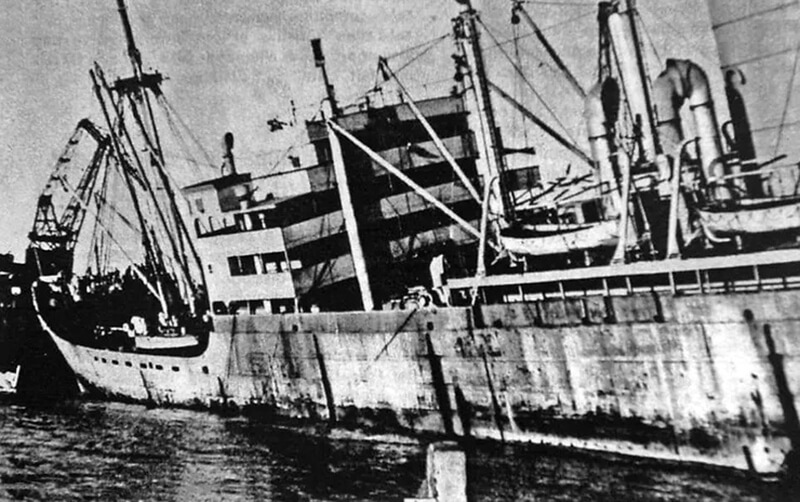

For the first time, ideal conditions prevail with a moderate southerly breeze and a cloudy sky that intermittently rains, darkening the night further and muffling the sounds of their paddling. Initially, they paddle up the center of the Garonne River, then switch to quieter, single paddle strokes as they stick close to the reed-lined western bank. Around 22:00, as they round a river bend, they glimpse their long-sought targets—two large ships moored at Bassens South on the eastern bank, well-lit and active with loading operations.

Inching forward cautiously, they spot a small floating pontoon pier opposite the ships, where a coaling lighter is moored. Unseen, they glide up to and under this pier, continuing a short distance before finding small water channels within the reeds. Here they navigate their canoes into the vegetation, settling side by side as the tide ebbs, embedding them in mud for concealment. This dense reed bed, towering nine feet high, provides an excellent vantage point and cover, allowing them to stand in their robust canoes, unnoticed.

Across the river, the cargo vessels—identified later as the ex-French Alabama and the German Portland—continue their bustling activities, oblivious to the raiders’ presence. Hasler and his team are enveloped by the daily life of a built-up area, yet remain hidden right in the midst of enemy activity. This proximity to their targets fills them with anticipation for the upcoming night’s operation.

| December 11th, 1942 |

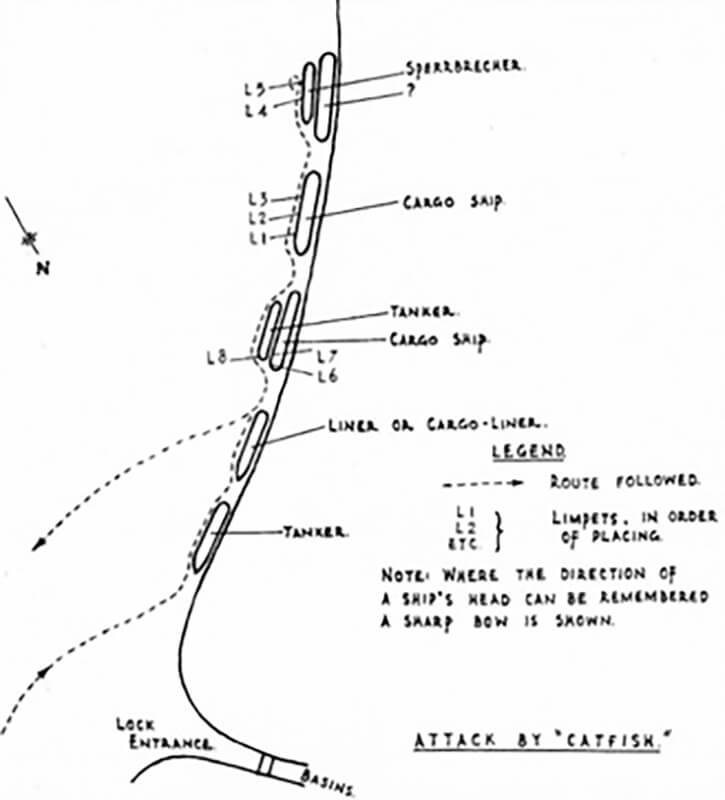

Throughout the day, they remain in their covert spot, discussing plans and timing for the attack in hushed tones, occasionally smoking, sheltered from light rain by their canoes. Hasler finalizes his strategy, aiming to align their movement with the tides to maximize stealth during the attack. They plan to start their offensive at 21:10, after the moon sets, to avoid detection while crossing its path, balancing the risks of visibility against the operational timing dictated by the tidal flows.

Hasler assigns Catfish the task of targeting the western bank of Bordeaux’s main docks, which lie three miles away. He instructs Corporal Laver in Crayfish to operate along the eastern bank toward Bordeaux East Docks, directing him to return and target the ships at Bassens South if no suitable targets are found on the eastern route. They are to act independently and, after completing their tasks, paddle back downstream on the ebbing tide as far as possible until halted by the next flood tide or the approach of daylight. Then, they are to make separate escapes on the eastern bank and scuttle their canoes.

Hasler holds onto the hope that Cuttlefish canoe team of Mackinnon, one of the missing, might still complete his mission. During the day, they reorganise their equipment in the canoes to ensure all escape gear is readily accessible. As evening approaches, they have their last meal in the canoes and proceed to arm their limpets with fuses. This is a critical moment, transitioning from preparation to action.

Using orange ampoules designed for a nominal nine-hour delay (which will probably extend due to the cold temperature), each man prepares his limpets. They insert the ampoules into the fuse caps, tighten them, and mark them with a cross to indicate they are armed. They also attach placing rods to ensure the limpets can be placed accurately and securely.

| Assault Phase |

This meticulous preparation takes over an hour as they work in unison under Hasler’s supervision, mindful of the time, moon, and weather. With both canoes fully prepared, compasses concealed, and faces camouflaged, they activate the time fuses at 21:00. The mines are now primed to detonate in approximately nine hours.

The tranquil weather, devoid of rain, wind, or clouds, creates a stark and pristine night as Hasler and his companion navigate the calm waters of the Garonne. Despite the idyllic starry backdrop, the glow of shore lights, including those from a nearby factory, prompts them to maintain a cautious distance of about two hundred yards from the shore as they approach their targets.

After approximately ninety minutes of paddling and manoeuvring around a river bend, they finally spot their objectives—several ships moored along the west bank, their decks awash in light, complicating the approach due to heightened visibility. Overcome with a sense of profound achievement akin to historical explorers, Hasler and Sparks press on, driven by a sharp hunter’s focus.

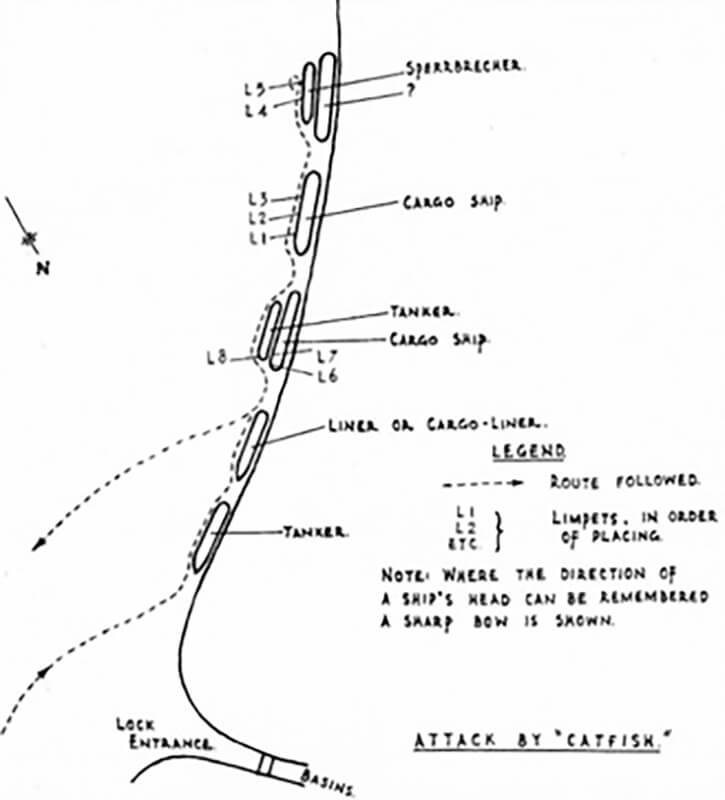

Approaching a well-lit lock, they navigate Catfish in a careful arc to avoid the illuminated areas, mindful that time is of the essence with the tide nearing its high-water slack. This tactical manoeuvre grants Hasler a chance to assess the ships from a safe distance, identifying seven potential targets—five directly at the quay and two others slightly apart.

Opting to bypass a tanker and a passenger-cargo ship, they aim for a more suitable cargo ship. However, an adjacent tanker complicates their approach. They find an ideal target soon after—a large, unobstructed cargo ship. Quickly, Hasler prepares to deploy the limpets. As the tide begins to turn, indicating the onset of the ebb, they execute their attack. Hasler plants the first limpet at the bow, then amidships, and finally near the stern, effectively setting the stage for significant damage.

Throughout this covert operation, the darkness is their ally, shielding them from view as they attach explosives to the unsuspecting ships. The only disturbances are the occasional outfalls and the noise of ship machinery, which they skilfully navigate. Their mission culminates as they reach the last ship, guarded by a small German naval vessel, complicating their efforts to secure the final target. Despite the challenges, their stealth and precision mark a critical point in their daring raid.

In the stealth of night, Hasler quickly assesses the German naval vessel before him. Although not his primary target, he recognizes the opportunity to use his remaining limpets effectively. Choosing to attach two limpets to the sperrbrecher, positioned near the engine room, they proceed with caution.

As they manoeuvre to depart, a clang from the ship’s deck alerts them to a sentry’s presence. Caught in the beam of his torch, they freeze, adopting a low profile in the shadows of the ship’s side, feeling exposed and vulnerable under the unwavering light. The tense moments stretch on as the sentry paces above, the sound of his boots echoing in the quiet night.

With no immediate reaction from the sentry, who perhaps dismisses them as driftwood, Hasler and Sparks take a calculated risk. They silently release their magnetic holdfast, allowing the ebb tide to carry Catfish away from potential danger. As they drift into safer waters, the absence of any alarm confirms their successful evasion.

Continuing downstream, they approach a cargo ship positioned next to a tanker. The proximity of these two vessels complicates their mission. Unable to access the cargo ship’s midsection due to the tanker, Hasler opts to place limpets at the stern and bow. In a heart-stopping moment, the ships begin to converge, nearly crushing Catfish between them. Quick action from Hasler and Sparks, pushing against the hulls, averts disaster.

Their escape from the tight squeeze allows them to circle around and attempt to place another limpet at the stern of the ship.

In the chilling calm of the river, Hasler and Sparks finalise their mission with precision. After planting their remaining limpets on the stern of a cargo ship and a tanker, they experience a rush of relief and exhilaration. Hasler, overcome with a bold sense of ownership over the river, opts for a daring and visible escape down the center of the Garonne, paddling vigorously despite the potential visibility to the enemy on both banks. This marks a shift from their calculated approach to a more reckless abandon, propelled by the success of their mission.

However, the gravity of their situation soon resurfaces. The transition from organized military operatives to fugitives in a potentially hostile environment looms large. Their journey back to safety will be arduous, requiring them to traverse at least 1,300 kilometres in harsh winter conditions without reliable resources. Yet, in the immediate aftermath of their successful attack, such concerns are distant thoughts. They focus solely on using the ebbing tide to carry them as far down the estuary as possible before daylight exposes them.

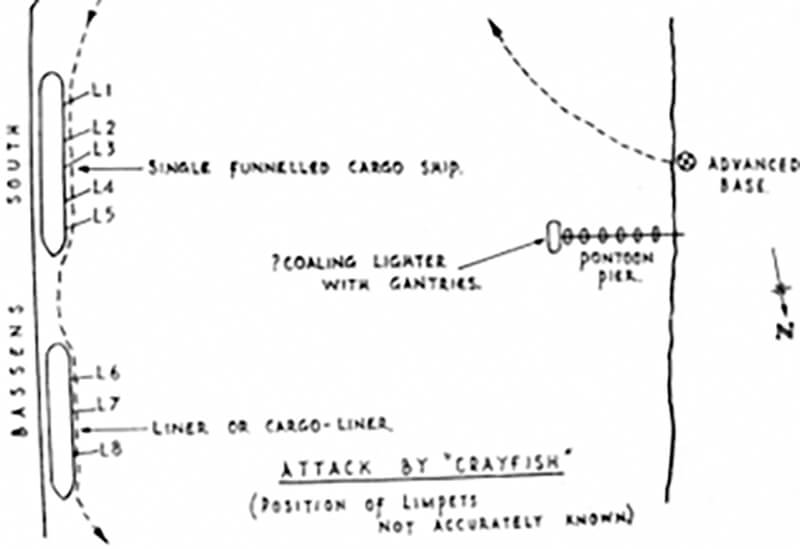

As they paddle past their previous hideouts and targets, they switch to double paddles, increasing their speed significantly. The quiet of the night is briefly disturbed by the sound of another canoe approaching rapidly. It turns out to be Corporal Laver. In the hushed tones of a clandestine operation, Corporal Laver reports to Hasler their actions along the east bank of the river. Unable to locate viable targets due to the changing tides, they redirected their efforts towards the previously identified ships at Bassens South. Laver details the successful placement of five limpets on the first ship and three on the second, all executed without encountering resistance or complications. The brief reunion in the dark waters is filled with whispered accolades and laughter, celebrating their success before acknowledging the need to separate and continue their escape independently.

| Escape Phase |

However, recognizing the need to adhere to their mission protocol, Major Hasler decides it’s time for them to separate and continue their retreat independently. Corporal Laver, longing for a bit more camaraderie, suggests they stick together a while longer. Hasler agrees but reminds him that they’ll need to part ways before reaching land to comply with their strategic plans.

| December 12th, 1942 |

Reunited, Catfish and Crayfish quickly resume their familiar roles for their final journey back into the Gironde. They navigate swiftly through the narrow passages between the Ile de Cazeau and the mainland, propelling the canoes with urgency to maximise their distance from Bordeaux before any potential uproar ensues. The tide, ever a crucial factor, dictates their pace. Once it turns, they risk being swept back upstream unless they find a landing spot.

Hasler, aware of the changing tides, veers towards the eastern bank, bypassing the dormant town of Blaye. They silently pass the anchored French liner De Grasse, which Hasler knows from intelligence is out of commission for the war. He silently wishes the ship luck for future voyages to New York.

Around 06:00, with dawn and the reversing tide looming, the raiders have advanced enough to consider landing. North of Blaye, in open country, seems a viable spot with a feasible escape route north eastward.

For five nights, the two canoes have manoeuvred through enemy waters, covering over 165 kilometres. As they prepare to part ways, Major Hasler signals to raft up one last time. Addressing Corporal Laver, he directs, “Well, Corporal, this is where we have to separate. You’re about a 1.5 kilometres north of Blaye. Head straight ashore here and follow your escape instructions. I’ll land a bit further north.”

Corporal Laver, only twenty-two and lacking extensive training, faces the daunting prospect of navigating foreign territory alone. Despite the challenge, he responds with composure, “Very good, sir. Best of luck to you.”

The separation is perhaps more poignant than their split for the night’s attack. Major Hasler, moved by the moment, thanks his comrades for their courage and resilience, expressing hope for a reunion back home. Sparks, always spirited, lightens the mood by promising a future pub meet-up, saying, “See you in the ‘Granada’. We’ll keep a couple of pints for you!”

With a mix of laughter and solemnity, they part ways, Major Hasler last glimpsing Corporal Laver and Marine Mills as they paddle determinedly toward shore, their canoe appearing both small and vulnerable against the vast waterway.

This would be the last time Major Hasler sees the brave duo. As he turns away, his heart heavy with the weight of farewell, he focuses on his immediate task, landing safely.

| The Limpet Mines explode |

From 07:00 on, the Limpet Mines set by Major Hasler and Corporal Laver activate sporadically throughout the day due to their imperfect timing mechanisms and sympathetic fuses. This leads to a prolonged and erratic sequence of blasts which catch repair crews off guard, fresh explosions occur while damage control is underway. Particularly at Bassens South, where Corporal Laver targeted the ex-French ship Alabama, enemy documents post-war indicate that explosions stretched from early morning until the afternoon. With the last of Corporal Lavet’s Limpet Mines going off around 13:00.

None of the explosives from Hasler’s Catfish detonate prior to 08:30, but when they do, they all go off within a short thirty-minute window.

The aftermath is chaotic. French fire and salvage squads, called to the scene, reportedly exacerbate the situation by using excessive water to douse the fires, inadvertently increasing the damage.

| Land Escape |

After detaching from Crayfish, Major Hasler and Marine Sparks continue paddling vigorously against the emerging flood tide for a short distance before aiming for the shore. They approach near St Genès-de-Blayee, disembarking onto soft mud which leads up to a familiar terrain of a six-foot mud cliff topped with tall reeds. They unload their escape equipment and proceed to scuttle their canoe, Catfish, by cutting up its buoyancy bags and slashing its canvas sides. Despite their attempts, the canoe remains semi-submerged due to the swift tide.

Major Hasler, feeling a pang of regret, pushes the canoe into the river, marking an unceremonious farewell to their reliable vessel. They then ascend the mud cliff, which proves challenging, and navigate through a noisy reed forest. Emerging into what appears to be a vineyard, they realise their path is complicated by the vine wires, forcing them to adjust their route frequently.

Using a compass, they maintain a general northeast direction, managing only about 2.5 kilometres by dawn due to their cautious navigation around potential hazards like farmhouses. As daylight breaks, they find refuge in a secluded wood, relieved to no longer manage the cumbersome canoes and the complexities of river navigation. Here, they enjoy the freedom and simplicity of being on foot, feeling liberated from their recent constraints.

Settling by a stream, they wash up and take turns resting, fully embracing the tranquillity of their surroundings. Sparks and Hasler reflect on their journey and the impending detonation of their limpet mines, which they won’t be able to hear due to their distance from the target. They spend the day recuperating, preparing for further travel inland to ensure a safe distance from the river and potential capture zones, planning to continue their escape under the cover of night in their uniforms.

| December 13th, 1942 |

Continuing through the night, Hasler and Sparks navigate by using only fields, footpaths, and cart-tracks, avoiding roads to stay clear of potential detection by car headlights. The vineyard wires frequently hinder their progress, making their travel exceedingly slow. By dawn, they manage only 13 kilometres and find themselves 1.5 kilometres south of Reignac.

Deciding it’s time to approach a farmhouse for assistance, they select one as the sun rises and approach it. They meet a farmer who appears indifferent and directs them to his wife for any requests. Hasler, with limited French, pleads their case for old clothes to disguise themselves. The farmer’s wife initially reacts with suspicion and indignation but eventually provides them with a beret and a cap, albeit begrudgingly. She urges them to leave quickly and not mention their visit to anyone, indicating the fear and risk involved in helping them.

Leaving the first farmhouse with minimal gains, Hasler and Sparks feel the inadequacy of their disguises and the looming risk of being reported. They continue to another farm, only to be turned away by a stern woman who refuses to assist them.

Persisting, they approach a third farmhouse. After a suspenseful wait, the kind-hearted madame of this house provides them with trousers, a jacket, and even a sack to carry their belongings. This encounter lifts their spirits significantly, and they finally begin to acquire the necessary attire to blend in as civilians.

After disguising themselves as civilians, Hasler and Sparks discard their military gear and bury their uniforms, pistols, and fighting knives. Dressed in the shabby clothes they have acquired; they transform themselves into the semblance of French peasants. Despite the discomfort of the old, worn-out trousers and jackets, they maintain some warmth thanks to their naval service underwear and additional cold-weather gear stowed in their sacks.

Hasler adjusts his distinctive moustache to a more common French ‘walrus’ style to blend in better, adding to their disguise. Satisfied with their appearance, they laugh, feeling they look like poor but respectable locals, despite their fatigue from a night of marching and a morning spent securing their new outfits.

Choosing to continue their journey without rest, they head towards Brignac, the first French village they dare to enter. Sparks finds the village notably different from English ones, with its utilitarian approach to space and picturesque yet brittle appearance. The village’s layout, with cultivated lands reaching up to the doors instead of quaint gardens, and the surrounding vineyards and olive groves, offers them a new and interesting environment.

In Brignac, their luck holds as they manage to acquire another sack for easier carrying of their supplies and a jacket large enough for Hasler. As evening falls, they opt against seeking shelter, not wishing to push their luck by asking for more help than they have already received. They retreat to the woods south of Donnezac, setting up a makeshift camp with bracken mattresses, wearing all their clothes, and covering themselves with the sacks for additional warmth.

| December 14th, 1942 |

Early and cold, Major Hasler and Marine Sparks rise at 06:30, an hour before daylight, and commence their day with a brisk walk to generate warmth. They now regularly traverse roads, passing through villages without hesitation. Adorned in typical rural attire, they assimilate into the local populace, thereby diminishing the risk of attracting attention.

They depend on specialised maps, which are superior to the standard silk escape maps issued to servicemen. These guides assist them in navigating the complex network of French country roads, avoiding main highways heavily trafficked by German forces and circumventing large towns where the presence of strangers might arouse suspicion.

Their journey that morning leads them through Donnezac while it is still dark, the early lights of farmhouses dotting the landscape signifying the start of another day. As daylight emerges, they manoeuvre through the perplexing layout of Rouffignac, a larger village that presents a significant challenge due to its numerous turnings and lack of signposts. The challenge of navigating unfamiliar towns without openly consulting a map or compass compounds the complexity of their escape.