| Page Created |

| March 18th, 2023 |

| Last Updated |

| March 26th, 2023 |

| Country |

|

| Special Forces |

| 1st Air Commando Group Chindtis |

| February 5th, 1944 – August 27th, 1944 |

| Operation Thursday |

| Objectives |

- Aiding Stilwell’s Ledo force in advancing towards Myitkyina by disrupting the Japanese 18th Division’s communication, obstructing its rear, and impeding its reinforcement.

- Enabling Yunnan Chinese forces to cross the Salween River and penetrate Burma by creating a favorable situation.

- Cause maximum harm and disarray to the enemy in North Burma.

| Operational Area |

Katha Area, Burma

| Unit Force |

3rd Indian Infantry Division

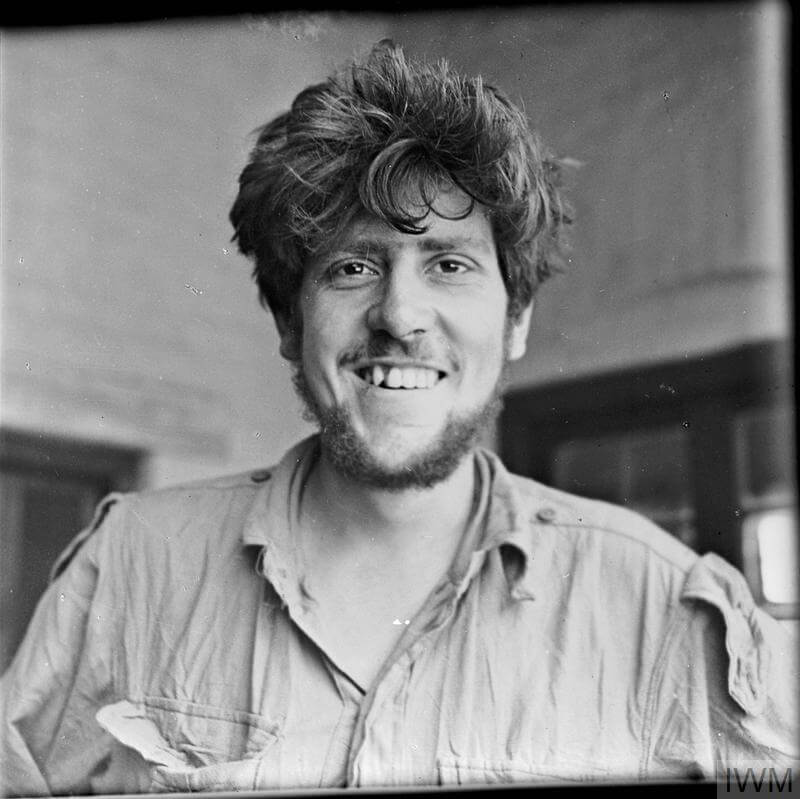

Major-General Orde C. Wingate

- 3rd West African Brigade (Thunder)

- 10 Headquarters Column, Brigadier A.H. Gillmore,

- 6th Battalion, Nigeria Regiment: 66 and 39 Columns

- 7th Battalion, Nigeria Regiment: 29 and 35 Columns

- 12th Battalion, Nigeria Regiment: 12 and 43 Columns

- 7th (West African) Field Company, West African Engineers (WAE)

- 3rd (West African) Field Ambulance, West African Army Medical Corps (WAAMC)

- 3rd (West African) Infantry Brigade Provost Section

- Details from West African Army Service Corps (WAASC)

- 14th Infantry Brigade (Javelin)

- 59 Headquarters column, Brigadier Thomas Brodie

- 2nd Battalion Black Watch: 42 and 73 Columns

- 1st Battalion, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment: 16 and 61 Columns

- 2nd Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment: 65 and 84 Columns

- 7th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment: 47 and 74 Column

- 54th Field Company Royal Engineers & Medical Detachment

- 16th Infantry Brigade (Enterprise)

- 99 HQ column, Brigadier B.E. Fergusson

- 2nd Battalion, The Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey): 21 and 22 Columns

- 2nd Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment: 17 and 71 Columns

- 51st/69th Regiment, Royal Artillery: 51 and 69 Columns

- 45th Reconnaissance Regiment: 45 and 54 Columns

- 2nd Field Company Royal Engineers & Medical Detachment

- 77th Indian Brigade (Emphasis)

- 25 HQ column, Brigadier Mike Calvert

- 1st Battalion, The King’s Regiment (Liverpool): 81 and 82 Columns

- 1st Battalion, The Lancashire Fusiliers: 20 and 50 Columns

- 1st Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment: 38 and 80 Columns

- 3rd Battalion, 6th Gurkha Rifles: 36 and 63 Columns

- 3rd Battalion, 9th Gurkha Rifles: 57 and 93 Columns

- 142 Company, Hong Kong Volunteers & Medical and veterinary detachments

- 111th Indian Brigade (Profound)

- 48 Headquarters Column, Brigadier W.D.A. Lentaigne

- 1st Battalion, The Cameronians: 26 and 90 Columns

- 2nd Battalion, The King’s Own Royal Regiment (Lancaster): 41 and 46 Columns

- Part 3rd Battalion, 4th Gurkha Rifles: 30 Column

- Mixed Field Company Royal Engineers/Royal Indian Engineers & Medical and veterinary detachments: Support

- Morris Force

- Lieutenant-Colonel J.R. Morris

- 4th Battalion, 9th Gurkha Rifles: 49 and 94 Columns

- Part 3rd Battalion, 4th Gurkha Rifles: 40 Column

- Dah Force

- Lieutenant-Colonel D.C. Herring

- Kachin Levies

- Bladet (Blain’s Detachment)

- Major Blain

- Glider borne commando engineers

- Royal Artillery

- R, S and U Troops, 160th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (25 pounders)

- W, X, Y, and Z Troops, 69th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery (40 mm Bofors)

- Divisional Support Troops

- 2nd Battalion Burma Rifles. One section assigned to each column except for columns in the 3rd West African Brigade

- 145th Brigade, Company Royal Army Service Corps

- 219th Field Park Company, Royal Engineers

- 61st Air Supply Company, Royal Army Service Corps

- 2nd Indian Air Supply Company, Royal Indian Army Service Corps

Galahad

- 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) (Merrill’s Marauders)

- 1st Battalion; Red and White Combat Teams

- 2nd Battalion; Blue and Green Combat Teams

- 3rd Battalion; Khaki and Orange Combat Teams

- 23rd British Infantry Brigade

- 32 HQ Column, Lancelot Perowne

- 1st Battalion Essex Regiment: 44 and 56 Columns

- 2nd Battalion Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding): 33 and 76 Columns

- 4th Battalion Border Regiment: 34 and 55 Columns

- 60th (North Midland) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery: 60 and 68 Columns

- 12th Field Company Royal Engineers & Medical Detachment

Air Support

- No.1 Air Commando Force (United States Air Force)

- 27th Troop Carrier Squadron (United States Air Force

- 315th Troop Carrier Squadron (United States Air Force)

- 31st Squadron (Royal Air Force)

- 62nd Squadron (Royal Air Force)

- 117th Squadron (Royal Air Force)

- 194th Squadron (Royal Air Force)

| Opposing Forces |

- 18th Division, Chrysanthemum Division, 菊兵團, Kiku Heidan

- 55 Infantry Regiment

- 56 Infantry Regiment

- 114. Infantry Regiment

- 124. Infantry Regiment

- 18. Mountain Artillery Regiment

- 12. Engineer Regiment

- 12. Transport Regiment

- 18/1. Signals company

- 18/2. Signals company

- 18. Sanitation company

- 18/1. Field hospital

- 18/2. Field hospital

- 18/3. Field hospital

- 18/4. Field hospital

- 18. Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department

- 18. Veterinary department

- 31st Division, Furious Division, 烈兵団, Retsu Heidan

- 31st Infantry brigade

- 58. Infantry Regiment

- 124. Infantry Regiment

- 138. Infantry Regiment

- 31. Mountain Artillery Regiment

- 31. Engineer Regiment

- 31. Transport Regiment

- 31. Signals Company

- 31. Ordnance Company

- 31. Sanitation Company

- 31/1. Field Hospital

- 31/2. Field Hospital

- 31/3. Field Hospital

- 31. Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department

- 31. Veterinary Department

- 31st Infantry brigade

| Operation Thursday |

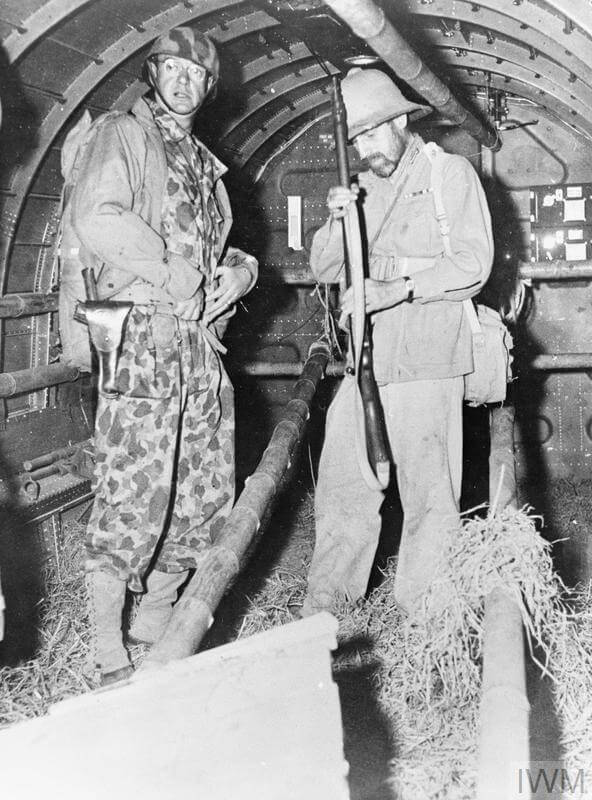

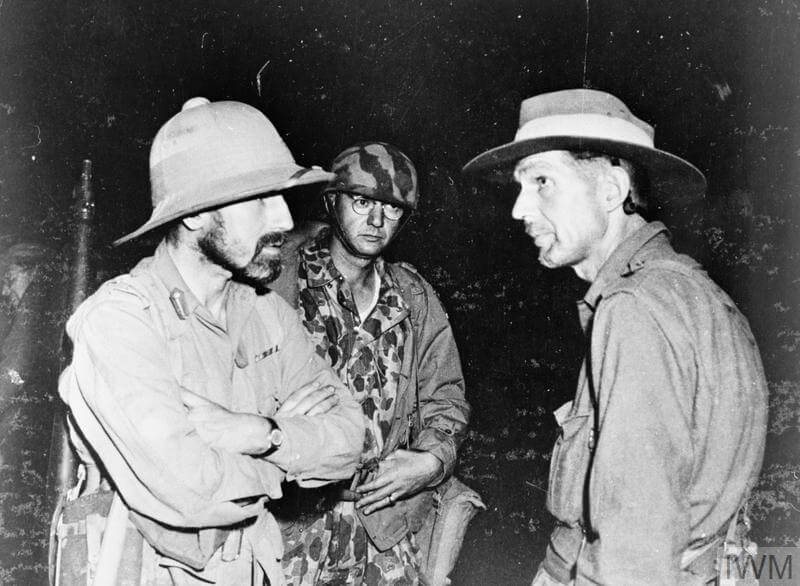

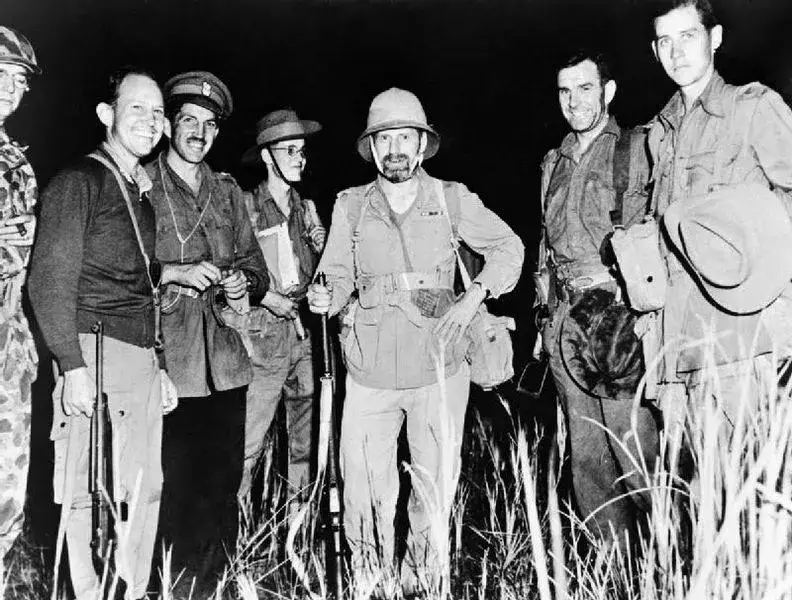

As elements of the 3rd Indian Division start to arrive at Broadway, they form into columns and head out into different areas of Northern Burma. Brigadier Calvert’s 77th Brigade drives west towards the railway line connecting Mandalay to the enemy airfield at Myitkyina. Their objective is to establish a roadblock near Mawlu to prevent supplies from reaching General Stilwell’s opposition, the Japanese 18th Division, in the Hukawng Valley. Meanwhile, Brigadier Lentaigne’s 111th Brigade pushes west-southwest towards Wuntho, with the goal of cutting off Japanese replacements heading north by rail and road. Brigadier Fergusson’s 16th Infantry Brigade, who are already exhausted from their trek across the Chin Hills, are tasked with capturing the Nippon supply hub of Indaw before the monsoons hit. General Wingate hopes to utilize the two all-weather enemy airfields of Indaw East and Indaw West. Additionally, a fourth LRP unit is deployed to Burma. General Wingate commits his reserve the 3rd West African Brigade to Broadway to provide garrison support.

In the third week of March, the Chindits are divided into four locations, waiting to strike the Japanese supply lines. Meanwhile, the P-51A Mustangs and B-25H Mitchells are actively attacking various targets in Northern Burma. However, when Brigadier Calvert reports that his brigade has set up a roadblock overlooking the railway line outside Mawlu, the focus shifts to close air support. Even though a semi-permanent stronghold is against the Long Range Patrol principle, the addition of airpower makes it possible for Brigadier Calvert to dig in and establish a perimeter with concertina wire. Airstrips are constructed nearby to continuously airdrop consumables for the troops. Despite repeated attacks, the stronghold known as White City holds strong, causing supply and munition problems for the Japanese 18th Division.

Five days later, the 16th Brigade is ready to attack Indaw, and the 14th Brigade is sent to assist Brigadier Fergusson’s exhausted men. Another airstrip, Aberdeen, is constructed northwest of Indaw using the same methods as Broadway. During the fighting, the Chindits are pinned down, and the P-51A Mustangs of the 1st Air Commando Group are called in for a napalm strike. The fighter pilots coordinate with the ground troops by marking enemy positions with mortar smoke and friendly positions with flares. Ultimately, the Chindits are able to retreat to safety after successfully separating themselves from the Japanese. Despite high casualties, the withdrawal is considered successful. During the first week of the operation, more than 150 light plane missions are conducted, over two hundred casualties are evacuated, and nearly 75 supply drops are made to support Aberdeen. The Japanese are determined to hold onto Indaw because it was a crucial supply hub that plays a significant role in their strategic plans for the conquest of India.

As the Chindits are being flown into Burma, General Renya Mutaguchi, the commander of the Japanese 15th Army, launches a three-pronged invasion into India called Operation U-GO. The 33rd Division advances from south of Tamu, the 15th Division from east of Imphal, and the 31st Division through the Tuza Gap east of Kohima. The Japanese 18th Division in the Hukawng Valley is also involved, tasked with blocking General Stilwell’s Chinese troops from joining the fight). General Mutaguchi decides to cut off the British from their supply depot at Imphal, as he believes the Japanese defensive posture in Burma is vulnerable, as a result of General Wingate’s first expedition known as Operation Longcloth. He hopes to interpose Japanese troops on Indian soil before the monsoons and generates favorable propaganda for a “March to Delhi” by Indian National Army leader Chandra Bose. The operation is planned to last less than a month, and the invading troops are provided only a 21-day ration of supplies. The Japanese move stores by the Shwebo-Imphal Road as well as the previous supply routes, as the only all-weather artery is between Shwebo and Imphal, but this route is near the area of General Wingate’s Chindits.

General Wingate feels he is on the verge of proving Long Range Patrol theory with the required major offensive now in being, and he immediately dispatches an optimistic letter to Winston Churchill about the situation. Unfortunately, within days of reading the news, the Prime Minister is shocked to learn the circumstances in Burma have changed drastically.

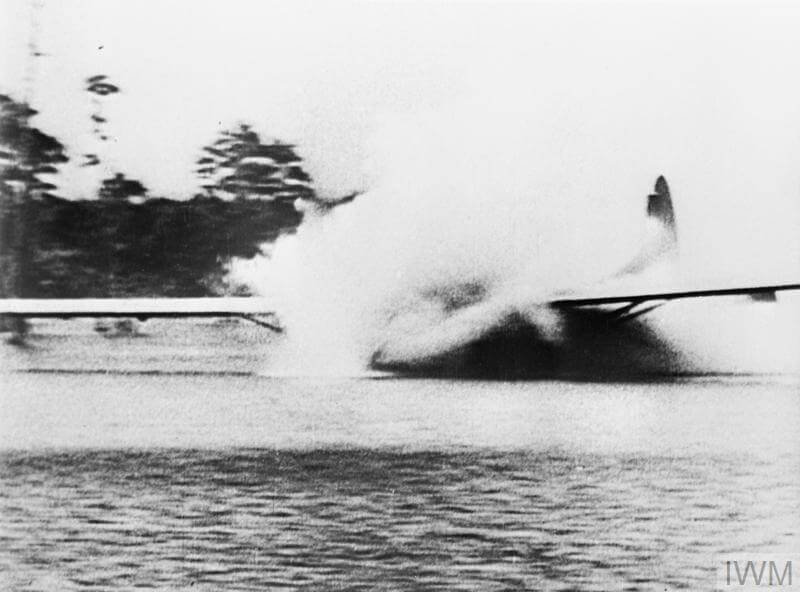

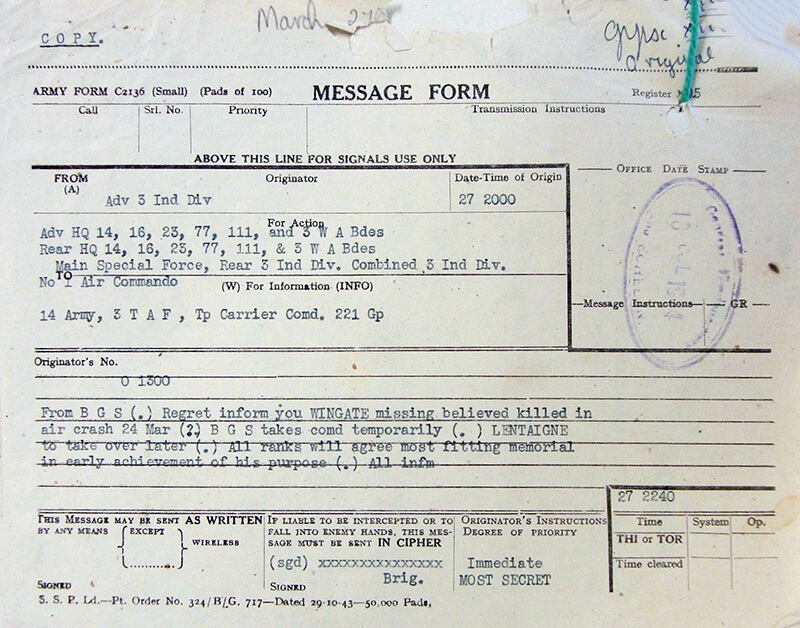

On March 23rd, 1945, General Wingate flies to the front lines in an L-5 to observe the operations and discuss strategy with his brigade commanders. After the conferences, he proceeds to Broadway on March 24th, 1944, where he boards an air commando B-23H. The aircraft heads west for General Wingate’s headquarters at Shylet after an intermediate stop at Imphal, but it never arrives. The Mitchell bomber inexplicably explodes into the side of a hill on the last leg of the journey, killing everyone on board.

In the middle of this complex operation in the theater, General Wingate’s death deprives the Allies of a dynamic and colorful commander. Brigadier Lentaigne, the most orthodox officer within General Wingate’s former command, is chosen as his successor over original Chindits and Wingate’s Chief of Staff. Although Lentaigne is a competent and heroic officer, he does not support the Long Range Patrol theory and is not impressed with Wingate. Despite this, the Chindit operations continue with air commandos providing ground support. The Japanese communication system is particularly vulnerable to one of the air commandos’ unconventional schemes, which required an unapproved modification to the fighters. A weight attached to a cable is dragged behind the fighter plane, and assault force pilots would use it to cut Japanese communications by diving on telephone and telegraph lines, wrapping the weight around the wires like a bola. Sometimes the lines snapped, and occasionally pilots uprooted telephone poles and dragged them for miles before jettisoning the cable. One pilot even uses his plane as a flying wire cutter after losing his cable assembly, slicing through several telephone lines.

Colonel Cochran’s men also provide support to all Chindit brigades in a more conventional role. They target Japanese surface and river lines of communication, which prove to be equally effective. Using new P-51B Mustangs, the assault force attacks the Shweli River bridge, which withstood previous bomber attacks by Eastern Air Command on several occasions. This bridge controls a vital supply route to Northern Burma. On April 21st, 1944, Major Petit demonstrates the precision of the dive-bombing Mustangs by scoring a direct hit with two five hundred kilograms bombs, causing the bridge to collapse. By the end of the campaign, the road and railroad system in Burma had become so confused that the Japanese were unable to move supplies from Northern Burma to their only usable traffic artery, the Shwebo-Imphal road.

Before officially coming under the operational control of General Stilwell on May 17th, 1944, the 3rd Indian Division is already ordered to move north toward Mogaung by him. The 111th, 14th, and 3rd West African Brigades are instructed to link up with Brigadier Calvert’s troops to assault the Japanese garrison there. In early May, the 16th Brigade, which has been in Burma longer than other units, shows signs of sickness, exhaustion, and strain, and General Slim orders their withdrawal. The other four brigades are also in poor shape, but General Stilwell does not allow their relief, fearing it would attract Japanese troops toward his position.

After planting landmines at Broadway, Aberdeen, and White City, the Chindits abandon their strongholds and begin moving north through the jungle and rice paddies. The 111th Brigade, now under the command of Colonel John Masters, is responsible for applying further pressure on the Japanese logistic lines. Masters’s force arrives at Clydeside on May 8th, 11944,and immediately faces fierce resistance. On May 9th, 1944, Colonel Masters requests gliders to build an airstrip at Clydeside, which is later renamed Blackpool.

Unlike White City, which is deep in the Japanese rear, and its defenders had ample time to prepare their defences, Blackpool is close to the Japanese northern front and is immediately attacked by Japanese troops with heavy artillery support. As Calvert and Stilwell have anticipated, abandoning White City has allowed the Japanese 53rd Division to move north from Indaw. Although a heavy attack against Blackpool is repelled on May 17th, 1944, a second attack on May 24th, 1944, captures critical positions inside the defences.

Due to the onset of heavy rainfall during the monsoon, movement in the jungle becomes extremely difficult, and neither Calvert nor Brodie’s 14th Brigade is able to provide assistance to Masters. Eventually, after 17 days of constant combat, Masters is forced to abandon Blackpool on May 25th, 1944, as his troops are exhausted. Nineteen Allied soldiers, who are severely wounded and unable to be relocated, are euthanised by the medical orderlies and concealed in dense bamboo groves.

During this time, the Allied Forces gain air superiority over Burma. A large part due to the success of the 1st Air Commando Group. The effectiveness of the air superiority in Burma is exemplified by the situation at White City, where the Japanese relentlessly attack the defended area. The assault force responds with frequent fighter and bomber attacks, while light planes are utilised to evacuate casualties from a small makeshift strip next to the railroad. In a display of initiative, an L-5 Sentinel pilot offers to fly Brigadier Calvert over the surrounding area to locate and record enemy concentrations. Using this new intelligence, Calvert requests bombing attacks within fifty metres to his own position. The accuracy and persistence of the air commando attacks prove too much for the Japanese troops, who eventually retreat, leaving behind their dead, equipment, and weapons. With help from Colonel Cochran’s men, the Chindits successfully block the rail line into Myitkyina for nearly two months, making the holding action by the Japanese 18th Division impossible.

Meanwhile, at Aberdeen, the 16th Brigade continues to use the 1st Air Commando Group and Troop Carrier Command to resupply their attempt to secure Indaw. However, a Japanese fighter pilot attacks a Royal Air Force Dakota on approach at Aberdeen, causing damage to the landing gear and one engine. After this incident, the Allies synchronise C-47 Dakota sorties to arrive and depart stronghold airstrips at dusk and dawn and assign fighter escorts to patrol the area.

Nevertheless, the L-pilots continue to fly unescorted sorties, establishing a reputation for courage and skill. When Merrill’s Marauders are pinned down at Nhpum Ga and their own L-4 Grasshoppers are unable to evacuate the sick and wounded due to the small landing strip, General Stilwell immediately orders the air commando L-1 Vigilants to evacuate the casualties. In total, the light planes evacuate over 350 hospital cases, showcasing the air commandos’ ability to fly out of places others could not.

According to General Arnold’s original plan, Colonel Cochran’s men are supposed to be relieved of duty and sent back to the United States on May 1st, 1944. However, the plan is changed because they want to protect the troops that are still in Burma. On May 17th, 1944, the 3rd Indian Division officially comes under the operational control of General Stilwell, who already ordered the 111th, 14th, and 3rd West African Brigades to move north towards Mogaung to link up with Brigadier Calvert’s men and assault the Japanese garrison there. The 16th Brigade has already been sent back to India in early May, showing signs of sickness, exhaustion, and strain due to their extended stay in Burma. The other four brigades are in equally bad shape, but Stilwell does not allow them to be relieved. He is afraid that their retreat would attract Japanese troops towards his position.

As Stilwell assumes command of the Chindits on May 17th, 1944, he orders the Chindits to capture heavily defended Japanese positions without support from tanks or artillery, resulting in heavier casualties. Under Stilwell’s command, the Chindits are misused and forced to undertake roles that they are not trained or equipped for.

Just before the monsoons hit, the Japanese air force makes a last ditch attempt to regain control over Burma, but it is too late. On May 19th, 1944, a flight of 16 Japanese warplanes arrives at Blackpool, but the air commandos are able to shoot down one bomber and two fighters without any damage to their own planes. However, the weather is now critically hampering their effectiveness.

Colonel Cochran tries to operate out of Eastern India as long as possible, but the rains turn the grass strips at Hailakandi and Lalaghat into mud pits. He eventually orders the air commandos back to Asansol, an abandoned British airfield in Central India, on May 23rd, 1944. The last UC-64 barely makes it through the bad storm, raising a “rooster tail” as it slogs down the grass strip for the final time.

After reaching Asansol, the 1st Air Commando Group experiences a decrease in personnel as Colonel Cochran convinces General Stilwell to send home those who have completed two tours of duty in the war, including himself. He leaves the command of the group to Colonel Gaty, who entrusts Lieutenant Colonel Boebel with leading the far-flung light plane section.

Upon taking over, Lieutenant Colonel Boebel orders all the light planes back to India, unaware that a part of his section remains in Burma to transport casualties to hospitals. As a result, the 111th Brigade retreats from Blackpool on May 24th, 1944, and moves west towards Lake Indawgyi. However, the American pilots from the Light Plane Force continue to provide invaluable support, shuttling the sick and wounded to safety. Colonel Masters describes their efforts as tireless, with the pilots arriving hour after hour and day after day to evacuate the casualties. Despite being short-handed, a group of eight light plane pilots continues to evacuate the sick and wounded until a new solution is found.

Finally, Colonel Masters convinces General Lentaigne to divert a Sunderland seaplane from the Bay of Bengal to Lake Indawgyi to assist in the effort. In total, almost four hundred casualties are airlifted to hospitals northeast of Dimapur. Upon discovering that some of his pilots were still in Burma, Lieutenant Colonel Boebel immediately orders them to return to India, marking the end of the 1st Air Commando Group’s actions during Operation Thursday.

From June 6th, 1944, to June 27th, 1944, Calvert’s 77th Brigade suffers eight hundred casualties, which is up to 50% of the brigade’s involved men, during the capture of Mogaung. Fearing orders to join the siege of Myitkyina, Calvert hands Mogaung over to Force X, shuts down his radios, and retreats to Kamaing. Avoiding court-martial, only after a personal meeting with Stilwell who comes to appreciate the harsh conditions the Chindits have been operating under.

After resting, 111th Brigade is ordered to capture Point 2171 but is left utterly exhausted. Only 119 out of the 2,200 men present are declared fit after medical examination. The brigade is evacuated, although the fit men, known as “111 Company,” remain in the field until August 1st, 1944, sarcastically kept there by Masters. Morris Force, the portion of 111th Brigade east of the Irrawaddy River, is led by Lieutenant-Colonel J. R. “Jumbo” Morris and spends several months harassing Japanese traffic from Bhamo to Myitkyina. Although they attempt to encircle Myitkyina, they are unable to do so, causing Stilwell’s anger. However, General Slim points out that General Stilwell’s Chinese troops have also failed. By July 14th, 1944, Morris Force is down to three platoons and only has twenty-five men fit for duty a week later. They are evacuated around the same time as the 77th Brigade.

The 14th Brigade and the 3rd West African Brigade continue to assist the newly arrived 36th Infantry Division in its advance south of Mogaung down the “Railway Valley.” Finally, they are relieved and withdrawn, starting on August 17th, 1944. The last Chindit leaves Burma on August 27th, 1944.

The actions of the air commandos and of the 3rd Indian Division have a far-reaching impact felt as far away as Imphal and Kohima. Despite initial success and fierce fighting, the Japanese U-GO offensive is eventually pushed back. As the Imperial troops retreat towards their previous sanctuary in Burma, General Slim pursues them with vengeance. Following the war, Imperial Army generals spoke of the failed offensive and made it clear that the airborne force’s penetration into Northern Burma had caused the failure of the Army plan to complete the Imphal Operations. The operation had several impacts, including preventing the 15th Army from advancing its headquarters until the end of April and causing a hostile attitude between the Army and its divisions in later operations due to inadequate communication. Supply transportation to units engaged in the Imphal Operations became very difficult due to damage to roads, and several divisions scheduled for the operation were involved elsewhere. The 5th Air Division was forced to operate against the enemy airborne unit, and the 18th Division fighting in the Hukawng area faced an increasingly difficult situation due to interception of the supply route. Lieutenant General T. Numata, Chief of Staff of the Japanese Southern Army, affirmed that the difficulty encountered in dealing with the airborne forces was a source of worry to all the headquarters staffs of the Japanese army and contributed materially to the Japanese failure in the Imphal and Hukawng operations.

| Multimedia |

| Operation Thursday in Pictures |