| Page Created |

| January 8th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| January 15th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Related Pages |

| British Biographies Special Air Service Biographies Long Range Desert Group Biographies Allied Biographies Axis Biographies |

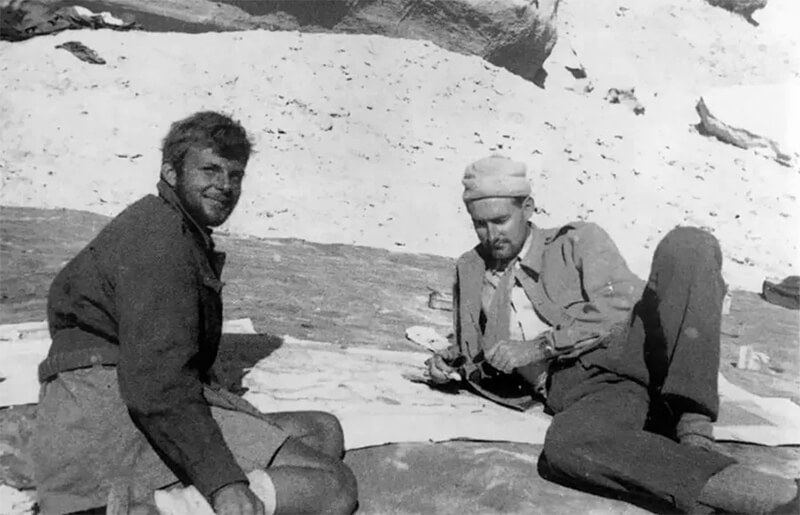

| Mike Sadler |

|

| Rhodesian Rifles |

| Long Range Desert Group |

|

| Special Air Service |

|

| Biography |

Born in London on February 22nd, 1920, Mike Sadler leaves school at 17 to study farming in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. As World War II begins, he enlists in the Rhodesian infantry but soon finds the task of guarding German internees dull. Claiming to be a key agricultural worker, Sadler secures his discharge, only to rejoin the military in the artillery. He serves as a gunner and later as an anti-tank specialist, with postings in Somaliland, Abyssinia (now Ethiopia), and eventually on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, preparing defences against a possible German attack on Suez.

| Long Range Desert Group |

Sadler’s career takes a pivotal turn during an evening out in Cairo. On leave, Mike Sadler encounters some early members of the Long Range Desert Group at a bar. He is recruited into the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) by its founder, Major Ralph Bagnold, a desert navigation expert. Comprising mainly ex-farmers from New Zealand and Rhodesia, the Long Range Desert Group appeals to Sadler, especially the romantic notion of navigating by the stars.

Initially considered for his expertise in weaponry, Sadler soon becomes captivated by the concept of celestial navigation. This interest leads to him being offered the role of navigator for the unit.

With only weeks to prepare, Sadler dedicates himself in perfecting his navigational skills, Sadler spends weeks learning techniques, including the use of a theodolite—a telescopic instrument with two perpendicular axes, traditionally used by surveyors for measuring angles in both horizontal and vertical planes. This device, crucial for desert navigation, shares similarities with the sextant, commonly used by mariners for sea navigation. He also immerses himself in learning how to interpret celestial charts, a crucial skill for navigating the vast and featureless expanses of the desert. Desert navigation, like its equivalent at sea, is largely a matter of mathematics and observation, but the good navigator also relies on art, hunch and instinct.

Quickly demonstrating an exceptional talent for desert navigation, Sadler becomes renowned for his “superhuman” skills in this area. His expertise proves invaluable during the Wadi Tamet raid and other missions where he leads forces across challenging terrains with remarkable precision.

| Special Air Service |

Later, at David Stirling’s request, Sadler joins the Special Air Service’s (SAS) L Detachment, earning the status of an “original” member.

Mike Sadler’s initial combat mission with the Special Air Service occurs in December 1941, marking the unit’s first ground operation following a previous failed attempt. His crucial role is to navigate from the Jalo Oasis to the German airfield at Tamet, a journey spanning over 650 kilometres of desert terrain. The mission, taking two days and three nights, is successfully executed without detection by the enemy.

Under the cover of darkness, the men of the Special Air Service infiltrate the airfield. They meticulously attach timed bombs to thirty aircraft. Additionally, they target ammunition and fuel dumps, as well as a building housing 30 Italian pilots and several German pilots. After setting the explosives, the team reunites with Sadler at a predetermined rendezvous point. As they make their escape, the bombs detonate, causing substantial damage. Intelligence reports later confirm that twenty-four aircraft are destroyed and nearly all the German and Italian pilots in the quarters are killed.

For his pivotal role in this successful mission, Sadler receives commendations. He is promoted to the rank of corporal and awarded the Military Medal for his bravery and skill. Recognising his exceptional navigational talents, Colonel David Stirling, the founder of the Special Air Service jeeps, appoints Sadler to the unit’s planning staff as the principal navigator. In this capacity, Sadler plays a key role in planning future Special Air Service operations.

During the raid on the Sidi Haneish landing strip on July 26th–27th, 1942 Mike Sadler, serving as the navigator, guides the men of the Special Air Service to their target, the German airfield at Fuka, near Sidi Haneish. This airfield, vital for General Erwin Rommel’s campaign in Egypt, is a significant base for Junker 52 transport planes. Approaching the airfield, the Special Air Service fires a green signal flare, marking the start of the attack. Eighteen Special Air Service jeeps then charge down the tarmac, opening fire on the parked Luftwaffe aircraft, including Stukas, Messerschmitts, and crucial Junker 52s.

Sadler, positioned to assist any wounded, observes the attack. The jeeps drive in formation, as rehearsed, and commence firing into the aircraft. The Vickers guns, loaded with a mixture of ball and tracer ammunition, quickly ignite the aircraft. Despite the German guards not being the primary target, they are overwhelmed by the intense fire. The raid, lasting around 10 minutes, destroys thirty-seven aircraft.

After the raid, a thick sea mist aids the jeeps’ retreat into the desert. The Special Air Service units disperse as planned, later reassembling at a prearranged rendezvous before heading back to base.

For his role in these two airfield raids, Sadler is awarded the Military Medal.

In January 1943, Mike Sadler is part of the team accompanying Stirling on his final Special Air Service patrol. Their mission involves crossing the Tunisian desert to meet with the British-American 1st Army. During the expedition, the entire patrol, exhausted from the long journey, falls asleep without setting up guards in a Tunisian wadi. Unbeknownst to them, they are discovered by Fallschirmjäger z.b.V 250, a German unit targeting British special forces. While sleeping near the leading jeep, Sadler is abruptly awakened by a poke in the ribs from a German soldier. Momentarily left unguarded as the German moves on to the next British soldiers a few metres away from them, Sadler and Johnny Cooper seize the opportunity to escape.

Joined by a French Special Air Service member, Sadler and Cooper, dressed only in their sleeping attire, embark on a grueling five-day trek across the desert. They cover a distance of some 160 kilometres, relying on a goatskin filled with water. Sadler’s expertise in navigation proves crucial in guiding them in the correct direction. Throughout their journey, they face severe hunger, subsisting on just a few dates. The harsh desert conditions, including intense heat, strong winds, and persistent flies, further test their endurance. When they finally reach the Free French lines, they are in a severely weakened state, with badly blistered feet and disheveled appearances, testament to the arduous nature of their escape.

Upon arrival in Gafsa, they are initially mistaken for German spies and are apprehended. However, the situation is resolved with the help of some Western journalists, including A.J. Liebling from The New Yorker, who recognises the significance of their story. Liebling interviews them, and his article, published in November 1943, brings the exploits of the Special Air Service in North Africa to the attention of the American public.

Their day concludes with a bit of relief when an intelligence officer from the Allied forces arrives with whiskey, offering some much-needed respite. After a brief conversation, the officer confirms their identities and acknowledges them as allies, ending their ordeal and confirming their status as part of the Allied forces.

| Europe |

This is also the end of Mike Sadler’s life in the desert. He is send back to Great Britain where is moves to Scotland. Here he recruits and trains soldiers for the Special Air Service

During the early stages of the D-Day Special Air Service operations, Sadler takes on the crucial role of Mission briefer and debriefer. His responsibilities include accompanying SAS members who are set to parachute into France, escorting them to their aircraft, and subsequently debriefing the aircraft crew following the drop. On occasion, Sadler has the opportunity to be on board the flight himself, allowing him to directly witness the parachute drops.

On August 7th, 1944, Sadler himself parachutes into France, accompanying the then-commander of the Special Air Service, Blair “Paddy” Mayne. Contrary to his usual role of leading from Britain, Mayne decides to lead his men from the front lines. After the drop, while Mayne diverges in pursuit of his next Distinguished Service Order (DSO), Sadler heads south with the objective of establishing contact with a missing SAS patrol.

Navigating in a jeep through German-occupied territory, Sadler undertakes the perilous task of reaching the missing patrol amidst the challenges and dangers posed by enemy forces.

| After War Life |

In his professional life, following the war, Sadler undertakes a year-long expedition to Antarctica alongside his formal commander in the Special Air Service, Blair “Paddy” Mayne. Sadler’s Passage in Stonington Island, Antarctica is named after him in recognition of his work there.

Post this adventure, Sadler joins the British Foreign Office, most likely MI 6, engaging in tasks believed to be of a classified nature. Throughout, he maintains a discreet approach to his post-war activities, often describing them simply as “foreign service work.”

He marries Anne Hetherington in 1947, but this union eventually leads to divorce. In 1958, he finds love again and weds Patricia Benson, who remains his companion until her passing in 2001. From this second marriage, he has a daughter named Sally Sadler.

Until his death, Sadler resides in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, about 150 kilometres west of London, having moved there a few years before his 100th birthday from a nursing home in Cambridge.

Despite progressively losing his eyesight, Sadler’s zest for life remains vibrant. He celebrates a significant milestone, his 100th birthday, in 2020 with a jubilant gathering at the Special Forces Club in London, surrounded by friends and peers who have been integral to his remarkable journey.

Mike Sadler died at the age of 103 on Thursday, January 4th, 2024.

| Multimedia |