| Page Created |

| April 6th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| May 26th, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Additional Information |

| Unit Order of Battle Commanders Operations Equipment Multimedia References Biographies |

| Badge |

|

| Motto |

| – |

| Founded |

| July 6th, 1942 |

| Disbanded |

| – |

| Theater of Operations |

| Europe Mediterranean |

| Organisational History |

| Introduction |

In 1941, Major Herbert George ‘Blondie’ Hasler, authors a visionary paper detailing methods for attacking enemy ships using canoes and underwater swimmers. At the time, his ideas are considered far ahead of their time, primarily because the necessary equipment to execute such operations has not yet been developed. As a result, Combined Operations rejects the paper, citing the lack of practical application for Hasler’s concepts without the appropriate technology and tools to support such missions. This rejection underscores the challenges innovators often encounter when their forward-thinking ideas surpass the existing technological capabilities or strategic thinking of their time, highlighting a common struggle to reconcile visionary concepts with contemporary practicalities.

The perspective on such tactics changes dramatically after the Italians’ successful attack deploying manned torpedoes of the Decima Flottiglia MAS (Decima Flottiglia Motoscafi Armati Siluranti) in Alexandria Harbour on December 19th, 1941. This attack severely damages H.M.S. Queen Elizabeth and H.M.S. Valiant. The same Italian unit had also previously damaged the cruiser York and the Norwegian tanker Pericles on March 26th, 1941, in the Mediterranean, and had been engaging in guerrilla warfare against merchant shipping near Gibraltar.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, perturbed by the incident, issues a directive to his Chief of Staff, General Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay, demanding an assessment of British capabilities in conducting similar bold operations.

Churchill’s intervention serendipitously benefits Major Hasler, when somebody at Combined Operations remembers his paper that covered more or less a similar method as the attacks by the Italians. These proposals, are now revisited by Combined Operations Headquarters, leading to Hasler’s recall for further discussion.

| Combined Operations Development Centre |

On the January 26th, 1942, Major Herbert George ‘Blondie’ Hasler takes up his role within the Combined Operations Development Unit under the command of Captain T.A. Hussey Royal Navy, (Previously known as the Inter-Services Training and Development Centre) located at the Royal Marines Eastney Barracks, Southsea. The primary mission of this unit involves the research and development of novel equipment, crafts, and materials to enhance amphibious warfare capabilities. This unit, with great foresight and sharp judgment but limited funding, has prepared excellent pre-war plans and developed the first of the assault landing crafts that would later prove invaluable.

Upon joining the Combined Operations Development Centre (CODC), Major Hasler immediately dives into his work with zeal. On his first day, he travels with Captain Hussey to Gosport to inspect an Italian “explosive motorboat” seized during the enemy’s attack on Malta on July 26th, 1941. The next day, he heads to the Combined Operations Headquarters (COHQ) for a meeting with Lord Mountbatten, facilitated by Tom Hussey, where his drafted terms of reference are approved. Hasler is tasked with studying, coordinating, and developing stealthy seaborne attacks by very small parties, focusing particularly on developing a British version of the explosive motorboat and enhancing methods for attacking ships in harbour.

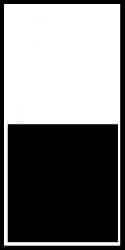

Hasler engages deeply in research on various devices and collaborates with numerous military and civilian experts. He leads a small ‘Experimental Party’ in Southsea, training them intensively. His initial projects revolve around the explosive boat, working closely with Vosper’s boatbuilders to adapt the Italian high-speed planing motorboat, equipped with a 225-kilogram charge at the bow, into a British variant. This version, named Boom Patrol Boat (BPB), is designed to allow the pilot to escape, unlike the Italian model where operators often surrendered after their missions.

His innovation extends to exploring alternative transport and delivery methods, including discussions with the Royal Air Force and civilian designers about launching small craft and swimmers from aircraft into enemy waters. A significant advancement includes adapting the explosive motorboat to be air-dropped by parachute, with trials conducted by Sir Raymond Quilter of G.Q. Parachutes Ltd.

Despite these technical developments, Hasler remains particularly interested in the potential of canoes for stealth operations, revisiting his initial 1941 proposals that advocated their use. He consults with experienced operators like Lieutenant-Commander Nigel Willmott and others who have used canoes in covert operations. Valuing their inconspicuousness, silence, and lightweight design, ideal for penetrating enemy defenses undetected, Hasler finds the existing canoes inadequate for complex operations, especially those involving submarines.

Determined to develop a more suitable canoe, Hasler commits to designing a new type. His comprehensive evaluations of various models and consultations with experts, including Professor Debenham from the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge, underscore his dedication to creating a canoe that meets stringent operational criteria, focusing on stealth, compactness, and ease of deployment from submarines.

| 101 Troop |

Early 1942, 101 Troop draws Major Hasler’s attention. Their leader Gerald Montanaro, a Regular officer of the Royal Engineers is known as one of the pioneering wartime canoeists. His troop rigorously trains in Scottish waters, mastering their Folbot-type canoes in strong currents and adverse weather conditions. They specialise in nocturnal operations and develop stealth techniques to stay nearly submerged and concealed during daylight. Inspired by their techniques, Hasler visits Dover to witness Montanaro’s successful raid on Boulogne Harbour, where they sink a large enemy tanker using limpets.

Gerald Montanaro and his team of the 101 Troop of the Army Commandos continually innovate in camouflage techniques, employing an ‘octopus suit’ and reversible flaps for their canoes. These adaptations allow them to switch color outlines from light to dark to evade detection by sentries on quays or ships. Montanaro himself also contributes to the development of a submersible mothership for raiding canoes, the Mobile Flotation Unit.

Despite these achievements, the Folbot-type canoe does not fully meet Hasler’s requirements, particularly intriguing him with Montanaro’s use of limpets and a placing rod. On March 31st, 1942, Montanaro demonstrates a special attack method in Dover Harbour, which Hasler participates in during a two-hour night exercise.

| Creating a Unit |

Motivated by the limitations of the Folbot, Hasler consults with Captain Hussey and later collaborates with Mr. Fred Goatley of Saro Laminated Woodwork Ltd. to design a new canoe, the Cockle Mark II. This canoe features a sturdy, flat, rigid bottom suitable for harsh operational conditions. The construction of the prototype begins shortly after, with Hasler and Goatley rigorously testing and refining it. The production of the Cockle Mark II eventually provides a significant advancement in stealthy waterborne operations for the newly formed special unit.

Major Hasler’s exploration into operational swimming broadens his innovative scope beyond just boats. He first comes across swim fins, already popular in California, when he captures a pair from the Italians during a raid in Alexandria. Traditionally, operational swimming relied on conventional strokes, but Hasler, already a qualified diver familiar with heavy diver’s gear and the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus (DSEA), consults with its inventor, Sir Robert Davis. Initially skeptical, Davis doubts the practicality of swimming long distances with the gear.

Hasler, undeterred, revolutionises his approach by integrating swim fins. He uses them along with a Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus set on summer evenings, hunting flatfish and pipefish along the Solent’s seabed near Southsea. His catch is not just for sustenance but also transformed into desk ornaments, blending utility with creativity.

On April 15th, 1941, Hasler’s focus pivots back to Boom Patrol Boats. He drafts a development paper that stresses the need for Boom Patrol Boats to be air transportable and launchable, which are currently under trials at Vosper’s. He presents this innovative document to Combined Operations Headquarters, sparking significant new ideas. After revising and gaining approval, Hasler elaborates on air transport methods at Combined Operations Headquarters.

Seeking to transition from experimental setups to operational deployment himself, Hasler gets a great idea on April 20th, 1942. Hasler thinks about establishing a dedicated unit. He envisions this unit using both Boom Patrol Boats and canoes, where canoes would manage surface obstructions and facilitate extraction after missions. This leads to discussions with Hussey about creating a Royal Marine unit under the guise of harbor patrol to mask their true purpose. The proposal emphasises the need for exceptionally high morale among the personnel.

On April 24th, 1942, Hasler pitches the formation of the Royal Marines Harbour Patrol Detachment at Combined Operations Headquarters During this meeting he highlights its defensive role to win support from the Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth. Lieutenant-Colonel H.F.G. Langley, Royal Artillery formalises this proposal on May 12th, 1942, advocating the joint operational capabilities of Boom Patrol Boats and Canoes to handle surface obstructions and aid in operations. In brief, the canoes handle obstructions and defenses, preparing the operational area for the Boom Patrol Boats to enter and complete the mission. The canoes then assist the pilots, who evacuate their boats before hitting their target, to escape.

By May 20th, 1942, Mountbatten approves Hasler’s proposals, albeit with a change in the unit’s name to the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment. The plan is forwarded to the Admiralty’s Director of Training and Staff Duties on May 26th, 1942.

| Raising a Unit |

During this challenging period, Major Hasler dedicates himself to intensive self-training, aiming to master his craft under a variety of conditions, enhance his physical endurance, and perfect the art of stealth. His objective is clear: to infiltrate enemy harbors undetected and escape without harm. Night after night, Hasler ventures alone into the dark waters, using either a canoe or his sailing dinghy, to refine his stealthy approaches. Although intercepted by patrol boats on two occasions, he successfully completes an all-night patrol on June 4th, 1942, landing ashore undetected.

Hasler’s preparation is comprehensive, extending beyond just watercraft. He undertakes long walks, continues his swimming routine, and practices with both a revolver and a Bren gun. He tests various techniques and tools critical for covert operations. These vary from choosing the appropriate varnish for the boat to reduce visibility, applying camouflage cream for facial concealment, and using fluorescent paint on key equipment for easy identification in the dark. He also explores survival logistics for extended periods in nature, such as eating, sleeping, and staying under a camouflage net in a hedge. Furthermore, he refines the optimal shape of a paddle for minimal silhouette and maximum efficiency, navigates without traditional tools, and devises methods for signalling other boats in darkness.

Following the approval of the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment, the Royal Marines Office at the Admiralty issues a recruitment call for “volunteers for hazardous service.” The advertisement aims to attract individuals who are “eager to engage the enemy,” “indifferent to personal safety,” and “free of strong family ties.” However, the response, while prompt, is not overwhelming, largely because many of the Corps’ most adventurous members have already enlisted in Commando service.

The volunteers who answer the call are a diverse group, coming from a wide range of backgrounds and with varying dispositions. Such recruitment efforts often attract not only the bravest of the brave but also those individuals known as scallywags, men for whom the regular strictures of military life are a poor fit, but who are attracted to the prospect of what promises to be a thrilling, somewhat piratical venture. These individuals see the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment as an opportunity to partake in the kind of daring and unconventional adventure that aligns with their more colourful and adventurous spirits.

In the weeks following the establishment of the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment, Major Hasler swiftly begins assembling his team, prioritising the recruitment of trusted and capable officers. His first strategic move is to secure Captain J. D. Stewart as his deputy. Captain Stewart, also known as Jock, had previously collaborated with Hasler in the Royal Marines Fortress Unit, making him a prime candidate due to their shared history and his proven reliability.

With Captain Stewart onboard, Hasler proceeds to meticulously select the rest of his team, ensuring a mix of skills and temperaments suited to the unit’s daring missions. He organises the unit into two operational sections, each commanded by a lieutenant and consisting of thirteen men. These sections are designed to carry out the core activities of the unit, focusing on direct engagements and operations requiring high levels of stealth and efficiency.

In addition to the operational teams, Hasler establishes maintenance and administrative sections to support the logistical and organizational needs of the unit. This structure brings the total strength of the detachment to forty-six members. This careful planning and organisation underscore Hasler’s strategic vision for the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment, setting a solid foundation for its future operations.

Major Hasler sets about forming his unit with zeal, beginning with the recruitment of two executive officers to lead the operational sections. Lieutenant J. W. Mackinnon, a native of Glasgow from a humble background, is appointed to command No. 1 Section. Mackinnon, who climbed the ranks from the enlisted to the officer class, is not only athletic and lively but also highly intelligent and full of initiative. Known for his patriotism and Vigor, he’s well-loved in the unit, often found playing jazz drums during their frequent social gatherings. Despite his tough training methods, his charismatic leadership fosters high morale among his men.

Lieutenant W. H. A. Pritchard-Gordon leads No. 2 Section. A distinguished and athletic figure educated at Shrewsbury, Pritchard-Gordon maintains a close friendship with Mackinnon, both having trained together as young officers.

The backbone of the unit is Colour-Sergeant W. J. Edwards, a steadying influence known as “Bungy,” who is instrumental in maintaining discipline. He’s supported by seven other Regulars, including Sergeant Samuel Wallace of No. 1 Section, a devoted and respected figure among his men, known for his strength and cheerful disposition.

After staying at the Barclay Hotel in Southsea, the officers established a Mess at No. 9 Spencer Road, Southsea. Later, when the enlisted men arrived, they set up quarters at No. 27 Worthing Road in Southsea with Mrs. Leonora Powell, whose husband was a member of the Royal Marines. At that time, No. 27 was operated as a guest house called “White Heather,” likely named after the Powells’ daughter Heather, who was 16 years old when the marines were billeted with them.

Hasler’s challenges include a lack of small boat experience among his volunteers, many of whom also cannot swim, a significant hurdle given the unit’s maritime focus. Nevertheless, training progresses with Hasler himself teaching boating skills due to a shortage of qualified instructors. This situation forces him to initially handle much of the training single-handedly, though he later delegates more responsibilities to his officers, particularly Jock Stewart, as the training regime becomes more established.

Despite their inexperience, the young officers quickly prove their worth, maintaining their authority and earning the respect of their men through close and personal leadership. Hasler, recognising the importance of traditional military discipline, consults with Lieutenant-Colonel J. P. Phillipps, reinforcing the necessity of maintaining parade-ground discipline to instil instincts vital for action. This adherence to traditional forms is crucial for unit cohesion and effectiveness.

Thus, the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment officially comes into existence on July 6th, 1942, at Lumps Fort, Southsea. Lumps Fort is a fortification built on Portsea Island as part of the defences for the naval base at Portsmouth. The detachment is based in two Nissen huts outside the fort adjacent to the car park as well as within the fort itself.

| Starting a Unit |

The Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment commences a rigorous training schedule on July 7th, 1942. Major Herbert George ‘Blondie’ Hasler, leading the unit, sets about assessing the new recruits. Despite his satisfaction with the selection, he acknowledges that many recruits possess limited small boat and canoeing experience, necessitating a thorough and prolonged training period. While the unit is being raised there are significant problems with the development of the Boom Patrol Boat.

The unit now focuses on the canoe aspect, as Hasler is convinced that developing the Boom Patrol Boat will be a lengthy process. He envisions that the canoes could also serve as an alternative for attacking ships. As the unit undergoes formation and training, the Vosper Company encounters a major challenge in sourcing a suitable engine for the boats. The only engine with sufficient horsepower available is the Lagonda V12 Engine, originally from the Lagonda V12 car. This engine must be removed and modified to fit the vessel; however, it turns out to be too heavy. As a result, the Vosper Company is urgently exploring alternative engine options.

From its inception, the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment fosters an extraordinary sense of unity and pride, viewing themselves as an elite group distinct from the rest of the military. This pride is partly fuelled by their exceptional physical fitness and the example set by the Regulars in the unit. Their distinct march, the “Southsea Stroll,” along with their impeccable off-duty attire in the handsome “blues” of the Royal Marines, further reinforces their esteemed identity. They live independently from barracks, which not only fosters a sense of responsibility but also removes the burden of administrative tasks, contributing to their sharp, responsible demeanour.

Training and relationships within the unit are intimate, with officers and men sharing many aspects of their military life closely. They train together, share accommodations, and even socialise together, yet maintain a respectful hierarchy that ensures discipline and camaraderie. Officers lead by example, never asking their men to undertake anything they hadn’t first tackled themselves.

Despite the close bonds, Major Hasler is careful about maintaining a balance between camaraderie and discipline. He recognises the potential risks of too much familiarity but sees the unit’s spirit as a vital asset worth preserving. This balance is key to maintaining morale and effectiveness, allowing for informal interactions without undermining the officers’ authority.

The unit also has a supportive and efficient headquarters staff who manage logistics and maintenance, contributing to the smooth operation of the unit. This includes dedicated storemen, Marine Officers’ Attendants, and support from the local Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens), who are integral to the daily functions of the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment.

The Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment benefits significantly from the support of a small naval workshop unit, which is crucial for maintaining and enhancing their specialised equipment, particularly the mechanically propelled explosive boats. This workshop unit is led by Lieutenant (E) R. W. Ladbrook, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, who was previously stationed at the landing-craft base on Hayling Island. Ladbrook and his team of ratings become increasingly vital as the unit’s operations expand, showing remarkable dedication and ingenuity in ensuring the operational readiness of the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment’s equipment.

The training headquarters and depot for Major Hasler’s team is modestly established in two Nissen huts located on the seafront of Southsea, strategically positioned near the historic Lumps Fort and Canoe Lake, a site where Hasler himself had learned canoeing as a boy. The proximity to these locations is not just convenient but also symbolically tied to the unit’s marine operations. Their administrative offices are set up at 24 Dolphin Court, previously occupied by the Combined Operations Development Centre, which has since moved to Combined Operations Headquarters in London and been renamed the Directorate of Experiments.

In Dolphin Court, the detachment enjoys certain luxuries and administrative advantages. Exploiting their obscure status as a new and somewhat mysterious entity under Combined Operations Headquarters, they adeptly maneuver to acquire useful stores and resources, often bypassing formal requisites and leveraging misunderstandings among local authorities. This includes drawing unexpected benefits from both naval and army supply chains, depending on their needs.

The Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment is tasked with the critical mission of disrupting enemy shipping within harbours, a role that requires exceptional skills in handling a variety of small craft. Initially, their primary tool, the Boom Patrol Boat, is still undergoing development, which necessitates a focus on basic seamanship and navigation across all ranks to prepare for future missions. Major Hasler’s approach to training emphasizes collective operations in formation to mitigate the risks associated with individual decision-making under pressure, ensuring that the team can operate cohesively and effectively during missions.

In the early days, the unit is equipped with only Mk. I two-man folbots, which are canoes with rubberized canvas skins stretched over a framework of battens. The original training, which includes using these canoes, lacks any specialised underwater swimming equipment. The team relies on the Davis Escape Submarine Apparatus, a device consisting of a breathing bag with a purifier on the back, supplied with oxygen. This setup is the most basic available for learning the necessary skills for both canoeing and underwater swimming.

It is essential to use oxygen rather than compressed air because compressed air would leave a trail of bubbles on the surface, while oxygen on a contained circuit does not. However, using oxygen carries significant risks, as it can eventually convert to carbon dioxide if not carefully monitored. Regrettably, the unit suffers the loss of an officer during training due to this issue.

The Mk. I folbots are entirely unsuitable for the tasks the men are undertaking. It is crucial that these boats can be dragged in a loaded condition across various terrains, not only sandy beaches but also rocky ones. In many instances, they even need to be pulled fully loaded across the countryside. The primary benefit of these Mk. I folbots is that they teach them how to canoe in all conditions and enable us to conduct navigational exercises. However, they are impractical from the perspective of being lifted into a mother craft or stored in the torpedo hatches of a submarine or similar vessels. Ultimately, they provide the basic training in seamanship required for handling the new type of boats that the unit would eventually receive.

Safety is paramount in all training activities. The strict enforcement of wearing life jackets during water-based exercises ensures that despite the steep learning curve and the inherent dangers of their training, there are no fatalities. This careful balance of rigorous training, adherence to safety protocols, and the youthful vigour of Hasler’s team lays the groundwork for the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment’s eventual success in highly specialized maritime operations. This foundation not only prepares them for the technical aspects of their missions but also instils a strong sense of discipline and teamwork essential for operating in high-stakes environments.

As the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment begins focusing on training for explosive boat operations, they quickly gravitate towards using canoes. Among these, the Mk II canoe becomes a key feature in the detachment’s story. Initially, the unit uses Mk. I folbots, but as said earlier these prove prone to leaks and lack durability. The Mk II canoe, collaboratively developed by Goatley and Hasler, is still in its prototype stage during the initial training phases but eventually replaces the Mk. I just before a significant operation of the unit.

The unit’s early days on the water are marked by enthusiasm tempered by inexperience. Their initial outing on July 24th, 1942, turns chaotic, with many of the Mk. I folbots capsizing, leading to an afternoon spent in recovery and salvaging efforts. This incident, detailed in Hasler’s diary, underscores the challenges faced by the unit but also highlights their resolve to improve and adapt.

Major Hasler is deeply involved in testing and refining the Mk. II canoe on July 28th, 1942, after an all-night patrol, demonstrating his commitment to perfecting this craft for operational effectiveness. He continually adjusts the design, including adapting larger boats for various roles within the unit, ensuring the Mk. II is a stealthy, efficient craft suited for the special operations envisioned by Hasler and his team.

Simultaneously, as the physical training unfolds, Major Hasler is also intricately involved in planning and supervising his men’s daily activities. He dedicates significant efforts to refining the prototype canoe, alongside attending strategic meetings at the Combined Operations Headquarters in London and later with the Admiralty in Scotland, demonstrating his comprehensive commitment to the project.

| Trainingsregime |

During this demanding period, the young officers and men face exacting requirements. These tasks require city lads to master nighttime navigation without lights, manage their craft in all conditions, and exercise a high degree of initiative, cunning, and deception. They need to swim underwater, handle explosives, draw maps, navigate on land, and devise escape strategies from the enemy both overland and by water.

The training is intense and often taxing. Many crew members initially struggle with navigation, leading to frequent capsizes and rescues. The primary cover for their unit—the patrol of the defensive boom—provides rigorous training, particularly at night. This boom, stretching for six miles and filled with both surface and underwater obstacles, serves as a challenging training ground. The crews are trained to operate both in formation and individually, enhancing their skills in stealth and self-reliance.

Training sessions vary from navigating challenging harbors to dealing with soft mud, where they learn the technique of using their canoe as a sledge to avoid sinking into the mud. Explosives training begins with handling smaller anti-personnel depth charges, providing practical experience and adding an element of realism to their exercises.

Physical fitness is paramount, requiring regular and strenuous exercises to prepare for the physical demands of their missions. Psychological resilience is also critical, as the solitude and silence of the missions often lead to hallucinations and tensions among crew members. Managing these mental challenges is as crucial as the physical preparations.

Stealth tactics are honed to perfection, involving various methods to avoid detection and disguise their movements, both on land and water. The training also emphasises the importance of maintaining night vision, with practical tips and scientific testing to enhance their natural abilities.

During this period of rigorous training, the young marines are often tasked with the art of stealthy approach, particularly during slack periods when naval patrol boats, manned entirely by Women’s Royal Naval Service personnel engaged in less active duties like sunbathing, present an unconventional training opportunity. These exercises enhance their skills in stealth, an essential component of their training, which also includes escape techniques from enemy-occupied territories. Such skills are vital for raiding operations, as they often entail the risk of being stranded among enemy forces.

Training includes day and night exercises in the local countryside to master inconspicuous movement and effective use of maps. Initiatives aren’t always planned; for instance, one night, returning after a bombing raid, some of the trainees respond to cries for help from a side street, leading to an impromptu rescue mission from a bombed shelter, despite an air-raid warden’s objections.

It is clear that the training regimen imposed on the men is as exhaustive and detailed as the canoe’s development. Covering a wide range of skills essential for covert operations, the program includes navigation, the handling of various small vessels, reading charts and tide tables, compass navigation, underwater diving, survival techniques, camouflage, map reading, stealth tactics, combat training, rope work, canoe maintenance and repair, sabotage techniques, explosives handling, and the use of secret communication codes for potential capture scenarios. The training also prepares them for writing potential last letters to their families.

Meanwhile, Major Hasler busies himself with logistical preparations for operations. He focuses on the storage of expedition essentials, the design of equipment such as the optimal type of compass, the best paddle shape, and modifications to the canoe to ensure it remains flood-resistant in rough waters. He evaluates what clothing and food would best suit their needs, alongside developing effective camouflage techniques.

These also include discussions on new technologies and equipment that could enhance operational effectiveness, such as the underwater glider and developments in parachute deployment techniques for canoes. He continuously tests and refines the equipment, such as the Cockle Mk. II canoe, to ensure it meets the rigorous demands of stealth operations.

The approach to deployment in distant operational theatres is a significant concern. Experimentation includes parachuting with canoes and the development of an inflatable canoe for sea drops, aligning with the broader strategy of using submarines for stealth insertion. Hasler’s engagements include frequent visits to Combined Operations Headquarters in London, consultations with experts, and overseeing tests that are crucial for the strategic deployment of the Cockle Mk. II.

By Autumn 1942, the section contains twenty-four men, all ranks. The “Boom Patrol Detachment” disguises the unit’s training activities in kayaks and diving under the cover name “Boom Patrol Boat”. They had 10 weeks of harsh training behind them and Major Hasler.

| Preparations for Operations |

On September 18th, 1942, Major Hasler, accompanied by Colonel Neville, Combined Operations Headquarters chief planning coordinator, scrutinises potential operations at Combined Operations Headquarters in London. No suitable operation emerges. Unexpectedly, over the weekend, Colonel Horton contacts Hasler, leading to his return to London by Monday. Hasler dedicates this day to examining the Bordeaux file, targeting the Bordeaux docks, quickly drafting a plan that Colonel Neville lauds for its unprecedented promptness.

Training intensifies from September 22nd, 1942, at Southsea, closely adhering to Hasler’s specifications. Despite the development of the Cockle Mk II, the operation remains shrouded in secrecy, known only to Hasler and his second-in-command, Lieutenant Jock Stewart. The mission is kept secret from the rest of the team until their departure.

Once officially approved, Hasler selects his team, leading Number One section and assigning Number Two section to Stewart. They move to Scotland on October 30th, 1942, for final preparations. At H.M.S. Forth in The Clyde, home of the Number 3 Submarine Flotilla, they focus on camouflaging their canoes and practicing the attachment of magnetic Limpet Mines, crucial for the anticipated conditions in Bordeaux. They participate in Exercise Blanket, a demanding training simulation that mimics the operational challenges of Frankton, including nocturnal navigation and daytime hiding while evading local defenses and patrols.

Despite Exercise Blanket falling short of its objectives and being deemed an unsuccessful rehearsal, Hasler’s honest discussion of the outcomes with Mountbatten leads to a constructive view. Mountbatten highlights the lessons learned from the exercise, stressing the importance of not repeating the same errors in the actual operation.

| Operation Frankton |

On December 7th, 1942, 13 Royal Marines Commandos from the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment embark on Operation Frankton, a bold raid targeting German blockade runners at the Bordeaux-Bassens docks. These ships are prepared to transport critical electronic equipment to Japan. Despite the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment’s recent formation and the kayak section’s short training period, the details of the mission remain highly classified, with the raiders only informed of their target two days prior. From a submarine off the French coast, five kayaks set out on the mission, although one is already damaged. They paddle 112 kilometres up the Gironde River, managing to inflict significant damage on four ships, though none are carrying cargo at the time of the attack. Tragically, eight canoeists either drown or are captured and executed under Hitler’s “Commando Order”. Only Major Hasler and his No. 2, Bill Sparks manage to evade capture, returning to Britain by April 1943. On return Marines Eric Fisher, Norman Colley, and Bill Sparks all join Bill Pritchard Gordon’s No. 2 Section.

| Captain Stewart takes the lead |

Captain Stewart, serving as the acting Major, remains in Great Britain to oversee Dolphin Court, the headquarters of the Unit at 24 Saint Helens Parade, Southsea, Hampshire, also known as the Combined Operations Development Centre (CODC). Hasler has instructed him, the day before leaving on the H.M.S. Tuna, to investigate swimming attacks. Hasler also reveals the existence of the Underwater Glider, which Hasler has been developing with the Special Operations Executive. Hasler informs Stewart about a letter from Lieutenant Bruce Wright of the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve, (RCNVR), who proposes the inclusion of American-style swimming fins in underwater swimming. Hasler has asked for him to be brought to Great Britain with his equipment.

Earlier the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment had procured the only available underwater diving dress, which includes the Sladen suit and the Davis Submarine Escape Apparatus (DSEA). However, the Sladen suit proves unsuitable for Hasler’s purposes; it is too loose-fitting, made of thin silk and rubber, covering the body and sealing at the wrists, with a hood featuring a small fixed-glass face piece that can be lifted as needed. The suit also incorporates roughly made canvas boots, allowing wearers to walk or crawl on the seabed, and a large breathing bag attached to the chest, connected to the hood by a gas mask breathing hose. Two large oxygen bottles, made from an aluminium alloy sourced from shot-down German aircraft, since such materials are unobtainable in wartime Britain, are carried on the back.

After Operation Frankton begins, Captain Stewart contacts Lieutenant Commander W. O. “Bill” Shelford, the Royal Navy Superintendent of Diving at H.M.S. Dolphin, located at Fort Blockhouse in Gosport. During their initial training with the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment, the men were trained in using the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus, and Lieutenant Commander Shelford had assisted them during this phase. Stewart requests Shelford’s assistance in developing a thin, flexible, close-fitting suit that enhances mobility for activities such as climbing in and out of canoes and other small crafts, whilst being easy to put on and effectively keeping the wearer dry. In response, Lieutenant Commander Shelford introduces Captain Stewart with the Diving Committee of the Admiralty. The Admiralty Diving Committee reviews this design and expresses scepticism, particularly regarding how the diver would maintain warmth in such a suit. Despite these concerns, Stewart insists that the design is essential for the tasks at hand after which the design is allowed by the Committee to be developed.

Lieutenant Commander Shelford then introduces Captain Stewart to the Dunlop Rubber Company. Although Dunlop has no experience in manufacturing diving suits, focusing instead on balloons, and flying suits, they take on the challenge. The collaboration results in a close-fitting suit made of rubberised stockinet, designed with a flexible neck large enough for a man to enter through. Rubber cuffs at the wrists ensure a watertight seal, and a separate hood is developed to accommodate the use of underwater breathing apparatus as needed.

To solve the issue of warmth, divers wear long underwear and a thick woollen under-suit beneath the new diving suit, effectively allowing them to operate efficiently in cold underwater environments.

At the same time, Lieutenant Wright from the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve arrives in Southsea to join the unit. His equipment is still en route by sea; the only item he could bring on the bomber that transported him to Great Britain was a diving mask. While training in the swimming pool with the unit, he familiarises himself with the Dunlop Suit, but they lack a set of fins. The Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment had previously experimented with two pairs of fins sent by Combined Operations Headquarters. One pair, sourced from Italian divers of the Decima Flottiglia Motoscafi Armati Siluranti, proved too small to be effective. The other pair, made of canvas and larger, was still not very useful.

It soon becomes apparent that Lieutenant Wright’s equipment has been lost, as the ship carrying it was sunk. Consequently, he sketches a design for the pair of fins he intended to bring. Captain Stewart then approaches the Dunlop Rubber Company, requesting the production of a pair of fins that could be attached to the Dunlop Suit, based on Lieutenant Wright’s design.

The Dunlop Rubber Company develops a pair of rubber fins that can be attached to the diving suit. Simultaneously, the Siebe Gorman company devises a breathing apparatus that can be attached to the diver’s back. The company invites Captain Stewart to Manchester, where a complete set, comprising the diving suit, breathing apparatus, diving mask and fins, is ready for use. After testing and using it in a local pool in Manchester, it becomes clear that the British frogman has been invented.

| Back to Cockles |

In late December 1942, a meeting is convened to streamline the requirements for Cockles and small boats across Combined Operations and Admiralty departments. Chaired by Admiral de Meric from the Department of Naval Equipment (DNE), the meeting included Commander Todhunter from the same department, and Commander A.C. Hardy from Combined Operations Headquarters among twelve other officers and department heads. The group concurs that the diverse types of Cockles previously ordered can be consolidated into five distinct models: two dories of varying lengths, a six-man rigid canoe, a six-man inflatable or collapsible canoe, and a two/three-man semi-rigid canoe designed to fit through a submarine’s torpedo hatch, this last model embodying the optimal features of all prior designs. However, they note that if a sufficiently robust semi-rigid canoe proved unfeasible, a rigid alternative might be necessary.

Though Lieutenant Wymer is absent, he is charged with collaborating with Mr. W.V. Holt of the Department of Naval Construction (DNC), in Bath to finalise the Staff Requirements for these designated types. Following this, the Department of Naval Construction will then outline the technical specifications. This meeting is soon to be eclipsed by another scheduled for just twelve days later in Southsea.

On January 7th, 1943, Goatley resumes developmental discussions around the Cockle canoes now with Captain Stewart. He addresses the issue of bow slamming in rough waters observed during the Mk. II canoe’s tank tests in September 1942. Goatley informs Hasler, prior to his departure, of his plans to modify the design to alleviate this issue, and although the overall design remains unchanged, he submits a revised bow design to Stewart. Additionally, he extended the chine inside the canoe to enhance its speed.

On January 12th, 1943, Stewart communicates with the Department of Naval Construction, expressing their interest in this type of craft, and forwarding Goatley’s revised drawings. He also inquiries about the expected delivery date of the Mk. II Cockles then in production, likely referring to the initial batch of seventy ordered by Hasler.

A significant assembly on January 26th, 1943, at Southsea sees various departmental representatives and operational officers converge to discuss a unified canoe design that can replace the existing Cockle Mk. 1, Mk. II, and the Cockle Rigid. Despite the Department of Naval Construction’s initial interest in the Saro Mk. II Cockle, it does not meet the new requirements, prompting the Department of Naval Equipment to propose a redesign of the new May-Luard canoe. However, this suggestion is not well received by the operational officers present, leaving the Department of Naval Equipment no option but to attempt a redesign of the Saro Mk. II Cockle to meet the updated needs.

Goatley, still actively involved and enthusiastic about contributing, is at that time 67 years old and not receiving any remuneration for his designs during his retirement. He is also beginning to develop the Mk. II* for the Department of Naval Construction. Aware of the production advancements, Goatley notes that Saro’s has arranged for sub-contracting seven hundred Mk. 2 canoes to Parkstone Joinery Co. Ltd in Dorset, and to Messrs Tylers Ltd in Gloucestershire. Parkstone requests Goatley’s presence to consult on the jigging process, part of the arrangement with Saro’s, leading to a planned visit in mid-March 1943.

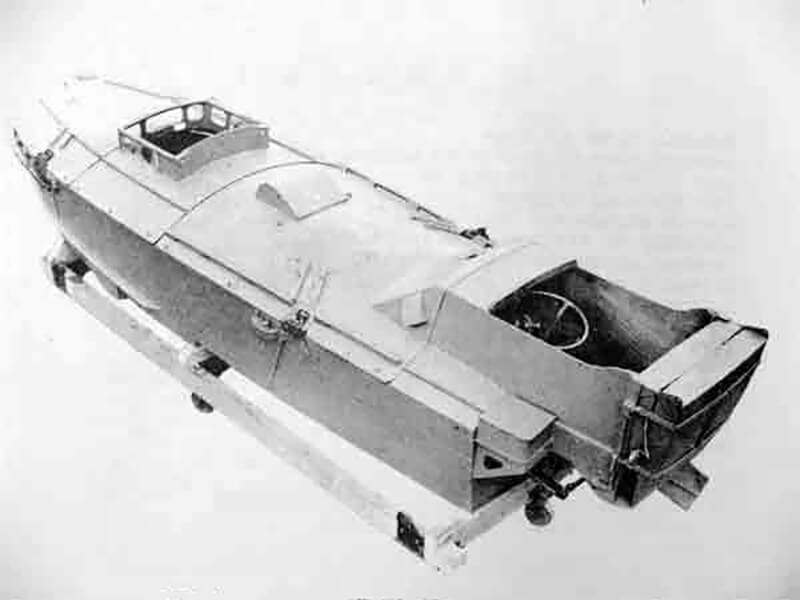

The Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment personnel also continues to contribute to the development of the Motorised Submersible Canoes (MSC), or “Sleeping Beauties”, of which the first arrive in July 1943. while training with the Motorised Submersible Canoe one young officer lost his life. Captain Stewart is witness of this event and tries to save the man without any success. Another young marine loses his life during training while using one of the breathing apparatus.

| Major Hasler’s return |

By that time Major Hasler had returned. Upon arriving he takes over command of the unit again from Captain Stewart. As shown earlier by that time the Frogman equipment is ready for use. Stewart and Hasler perform several trials with the frogman equipment for deep water diving at the Tolworth, Surrey. They did a lot of experimental work often being covered with bruises due to the lach of padding. The idea behind these experiments is if they could do it the men of the unit could also do it.

Meanwhile, the Commanding Officer of the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment faces ongoing challenges. He needs to resolve diving issues with the Underwater Glider, being developped by the Special Operations Executive. Hasler conducts increasingly longer underwater endurance swims, and oversees the first parachute drop of the Boom Patrol Boat. They also evaluate other equipment like the paddle board. This piece of equipment is eventually turned down due to the fact that it was an too obvious shape during operations.

Another piece of equipment the unit evaluates is the Intermediate Carrier. This is a 7.5 metres long vessel with the engine placed forward so it could carry two fully loaded Canoes in the stern. This vessel is developped to deliver the canoes to the operational area since the unit expected that the Admirality wouldn’t allow to use submarines anymore.

Moreover, hardly a week passes without least two trips to London for discussions concerning the future of the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment, the formation of Bruce Wright’s Sea Reconnaissance Unit, and often, the integration of similar formations under army control. Even a repeat of Operation Frankton is considered on August 19th, 1943, by the Combined Operations Haedquarters Plans Committee but is postponed on his advice until underwater swimming techniques had evolved further.

By late 1943, it becomes apparent that the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties (except those designated for the European invasion) and the Special Reconnaissance Unit are being relocated to India. Meanwhile, the Combined Operations Development Centre remains a hub for innovative thinking in small boat operations, even as the European theatre grows less conducive to such activities. It is therefore not surprising when Lord Mountbatten summons Hasler from Delhi to coordinate small boat operations in the South East Asia Command (SEAC) under the umbrella of the Small Operations Group. Despite his transfer to Bombay over Christmas, his connection with the European theatre is not severed. Following the Italian surrender on September 9th, 1943, and with their equipment now available for analysis, notably that of their Boat Assault Unit, the Decima MAS, which demonstrated remarkable bravery in small boat/underwater operations, Major Hasler is sent in January 1944 to assess any valuable insights firsthand. On February 18th, 1944, he reports back to Commander Combined Operations in London, now Major-General R.E. Laycock, that all members of the Italian Decima MAS seem were keen to engage against Germany. He also reports that he has not revealed any details of the British research while managing to gather much useful information about their equipment and techniques.

The visit offers a fascinating glimpse into the former enemy’s mindset and their apparent lack of advancement since their initial successes, particularly in the realm of breathing apparatus. Consequently, Major Hasler concludes that there is limited learning to be garnered from them and, despite their new allegiance, advised maintaining a cautious approach to information exchange while the advantage remains with us.

By the end of 1943, Major Stewart is requested by Combined Operations Headquarters to reevaluate the Bordeaux area. South of Lac Gironde lies Le Lac, home to a Dornier flying boats that conducts reconnaissance flights across the Atlantic to spot Allied convoys. Upon reviewing the proposed attack plan, Major Stewart concludes that he cannot approve it, noting that the lake is encircled by forest, making it unsuitable for dropping parachutists and their equipment. He suggests an alternative approach: dropping directly onto the lake and approaching the aircraft using a small inflatable raft.

Combined Operations Headquarters approves this new plan, and Major Stewart once again collaborates with the Dunlop Rubber Company to develop the required equipment. The innovative design features a two-piece raft: an interior raft that can float independently, allowing soldiers to keep their equipment and explosives dry, and an exterior raft that remains deflated during the jump but inflates upon hitting the water, capable of supporting the soldier’s weight and his equipment.

Lieutenant Pritchard-Gordon and his section are assigned to the operation. After briefing they follow, specialised training at Saint Andrews, Scotland chosen for its similarities to the target location in France. The training regimen includes parachuting into Loch Leven and swimming with essential equipment contained in a suitcase towards a predetermined target. After several weeks of intensive preparation at Saint Andrews, now involving a team of eight Royal Marines, the operation was unexpectedly cancelled, leaving the team with skills specifically tailored for a mission that would never be carried out.

As preparations for the operation progress, they receive intelligence that the Dornier flying boat has relocated to another base, resulting in the cancellation of the mission.

In November/December 1943, Lieutenant Pritchard-Gordon and the Earthworm section head to the Middle East to target Axis shipping in the Mediterranean and Aegean, clearing the way for operations by Raiding Forces Middle East, including the British Special Air Service, the Special Boat Squadron, the Long Range Desert Group and the Greek Sacred Squadron. The section involved in this mission comprises sixteen individuals, including two officers and twelve operational personnel, alongside a driver, two storemen, and a Military Operations Assistant. Many operations in this area are speculative, as at the time of planning, the harbours did not contain sufficient enemy shipping to justify a canoe attack.

The deployment is under the direct authority of the Flag Officer, Levant and East Mediterranean, Vice-Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings. The mission involves engaging enemy shipping in the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, with the primary goal of facilitating the clearance of pathways for raiding forces operating in the Middle East. This strategic operation was a crucial part of broader efforts to enable raids on the Aegean Islands and Crete, effectively laying the groundwork for subsequent actions towards Italy. The headquarters of the unit is based in Azzib, Palestine.

In Chichester Harbour, the unit adapts a sailing barge named the Celtic for use in training with the Boom Patrol Boat. The Celtic serves as a training base for the Boom Patrol Boats, accommodating the training boats which can be lifted out of the water. After some initial training in Chichester Harbour, the Celtic sails up to Scotland, near Oban in Loch Creran just off Loch Linnhe, with another temporary operational base in Lerwick on the Shetland Islands. At the advanced operational training base, they also take possession of the Combined Operations depot ship H.M.S. Quentin Roosevelt. Here, they set up advanced training with the Boom Patrol Boats, the cockle canoes, and the intermediate carriers, preparing for the future of the unit. This location allows them to practice with their equipment discreetly.

Meanwhile, Major H.G. Hasler, is promoted to Acting Lieutenant-Colonel on December 13th, 1943. Shortly thereafter, on December 18th, 1943, he is appointed at the Combined Operations naval base of H.M.S. Braganza in Bombay as Officer Commanding Special Boats Units, South East Asia Command. However, this role is short-lived, as by January 25th, 1944, he is re-appointed Officer Commanding Small Operations Group. Despite holding this official title, the group has not yet been formally established; for internal Royal Marines administrative reasons, he is scheduled to be re-appointed on April 24th, 1944, to Royal Marines Detachment 385. Nevertheless, he effectively continues as Officer Commanding Small Operations Group until the official formation of the group under a Royal Marines Commandant on June 12th, 1944. Captain Stewart (acting Major) takes over the command of the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment.

| Restructure |

The Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment is structured into a headquarters and administrative group comprising thirty-four members across all ranks, tasked with both the unit’s experimental endeavours and administrative duties. The operational side of the unit is divided into three distinct groups: A Group, consisting of sixteen members; B Group, made up of six members; and C Group, with seventeen members.

In June 1944, a significant Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment raid severely damages two destroyers and sinks three other vessels in Laki harbour, Leros, which the Royal Air Force ultimately sinks as they are towed to Piraeus for repairs. The elimination of these destroyers allows the highly successful raid on Simi by the Special Boat Squadron and Greek Sacred Squadron. In October 1944, the waning effectiveness of their operations precipitates the return of the Earthworm section to Great Britain.

The administration of the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment is transferred from the Commander Combined Operations (CCO) to the Deputy Director Operations Division, Irregular (DDOD(I)), who are already overseeing the Mobile Flotation Unit (MFU). This shift aims at improving the coordination of administration, training of Special Forces personnel, and the development of special craft. To support this objective, a captain is appointed specifically to coordinate the training of Special Service personnel under the Deputy Director Operations Division, Irregular. Approval for the commissioning of a dedicated establishment is given on August 28th, 1944, at Teignmouth, where the Mobile Flotation Unit is already been stationed for several weeks. This strategic realignment facilitates a more streamlined approach to the training and operational preparedness of Special Forces units. and moves to this shore base of H.M.S. Mount Stewart in Teignmouth, Devon.

During the autumn of 1944, the unit begins training for an operation using Boom Patrol Boats against the submarine pens in Bergen. The plan involves dropping the Boom Patrol Boats from aircraft. The unit training with these boats under command of Lieutenant David Cox relocates to Lincoln to join No. 617 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, which is tasked with dropping the boats. Throughout the autumn of 1944, the boats are repeatedly loaded onto the aircraft but are unloaded due to the persistently clouded weather in Norway. By Christmas, the operation has still not been undertaken, and the unit is sent on Christmas leave.

After Christmas, the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment starts training an American unit in the use of their equipment. However, in January 1945, Major Stewart becomes ill from tuberculosis and is admitted to the hospital. He probably contracted the illness from the frogman training. Major W. Pritchard-Gordon who has just returned from the Middle East, takes over the command of the unit.

Despite continuing its role in training and experimental activities, the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment’s anticipated deployment to the Far East does not materialise as the war comes to an end. By the end of 1945, the Teignmouth base is closed, resulting in the transfer of all craft and equipment belonging to the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment and other Teignmouth-based units of the Deputy Director Operations Division, Irregular, to the P.K. Harris shipyard in Appledore, known as H.M.S. Appledore.

| Surviving the War |

Remarkably, the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment is one of the three British Special Forces units to emerge intact from the Second World War, alongside two other Special Service units: the Royal Marines Commandos and the Parachute Regiment. With the war’s end, it is determined that the Royal Marines will assume responsibility for future amphibious operations. As a result, upon their return from the Far East, units such as the Special Boat Squadron, the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties, the Sea Reconnaissance Unit, and Detachment 385 are integrated into the Royal Marines, under the leadership of Hasler.

Transitioning into the post-war era, in 1946, the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment evolves into the School of Combined Operations, Beach and Boat Section, located in Fremington, Devon. This establishment swiftly transitions into the Combined Operations Beach and Boat Section. By 1948, it is rebranded as the Small Raid Wing within the Royal Marines Amphibious School. By 1950, this wing is reorganised into the Special Boat Wing, comprising various “Special Boat Sections.” The contemporary Special Boat Service proudly acknowledges its heritage, tracing its lineage directly back to the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment, underscoring a rich history of innovation, bravery, and strategic importance within British military operations.