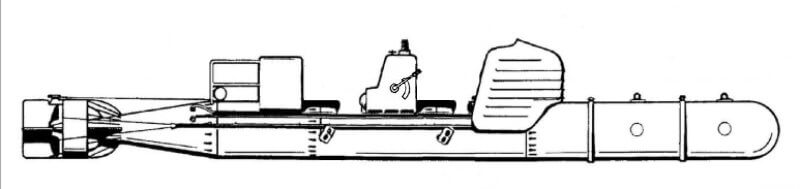

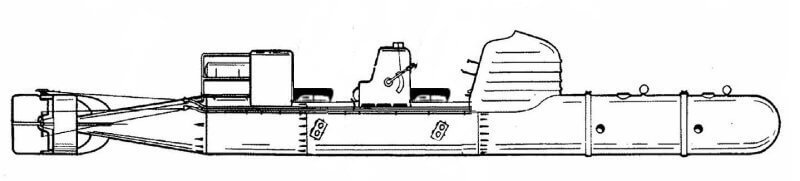

| Length |

| 7.3 metres |

| Wide |

| 0.53 metres |

| Height |

| 0.53 metres |

| Weight |

| 1,400 kilograms |

| Propulsion |

| 1.6 horse power electric motor |

| Armour |

| – |

| Armament |

- explosive charge of 300 kilograms

| History |

|

The Siluro a Lenta Corsa, colloquially known as the Maiale or Pig serves as a human-guided underwater assault craft operated by the Regia Marina during the Second World War. Modelled after a standard torpedo, the Siluro a Lenta Corsa is modified to accommodate two operators equipped with autonomous breathing apparatus, enabling them to covertly attach explosive charges to the hulls of enemy ships at anchor. The nickname Maiale or Pig is coined by Teseo Tesei, the engineer and naval officer instrumental in modernising the design. The term originates during an exercise when a frustrated sailor refers to the cumbersome craft as a pig, a label that is later adopted as a code name for secrecy.

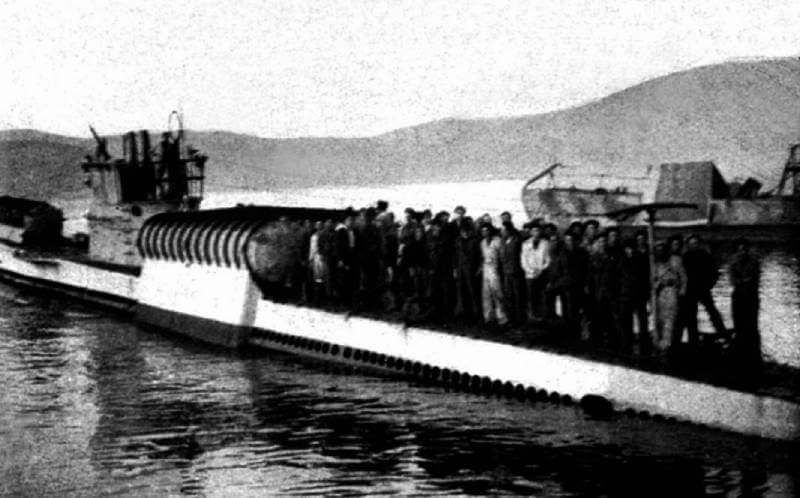

The Siluro a Lenta Corsa is deployed extensively by the Decima Flotilla MAS of the Regia Marina, targeting vessels within heavily defended ports in sabotage operations.

The roots of Italian assault craft trace back to the First World War, where the unique strategic circumstances prompt the Regia Marina to innovate weapons capable of infiltrating Austro-Hungarian naval bases. With no opportunity for decisive fleet engagements, Italy focuses on unconventional warfare, leading to the creation of MAS torpedo boats, “Barchini Saltatori” (jumping boats), and the “Mignatta,” conceived by Raffaele Rossetti and Raffaele Paolucci.

The Siluro a Lenta Corsa evolves directly from the Mignatta, the manned torpedo that successfully sank the Austro-Hungarian battleship Viribus Unitis during the First World War.

In 1935, during the height of the Ethiopian crisis, Teseo Tesei and Elios Toschi, two captains of the Genio Navale and engineers aboard La Spezia Group’s ‘H’ class submarines, begin developing the concept. In this context, Captains Teseo Tesei and Elios Toschi of the Genio Navale propose the “semovente,” an underwater adaptation of the Mignatta. Tesei had nurtured this idea since 1927 during his time at the Naval Academy, before qualifying in naval and mechanical engineering. The project centres on modifying a 533 millimetres torpedo to transport two operators equipped with self-contained breathing apparatus. This device would deliver an explosive charge discreetly to the hull of enemy vessels at anchor or in port.

Concurrently, Admiral Aimone di Savoia-Aosta advocates for “explosive motorboats,” designed to be transported close to their targets by Savoia-Marchetti SM.55 seaplanes, a concept inspired by his brother, Amedeo, Duke of Aosta.

These initiatives lead to the authorisation of experimental trials by Admiral Domenico Cavagnari, Chief of Staff, resulting in the development of Italy’s two principal types of assault craft during the Second World War: the Siluro a Lenta Corsa and the Explosive Motorboat (Motoscafo Turismo, or MT).

The Regia Marina accelerates its assault craft programme by further developing the ‘self-propelled torpedo,’ overseen by Captains Tesei and Toschi. This updated craft improves upon the Mignatta, offering increased speed, greater operational range, and the capacity to infiltrate enemy naval bases while submerged.

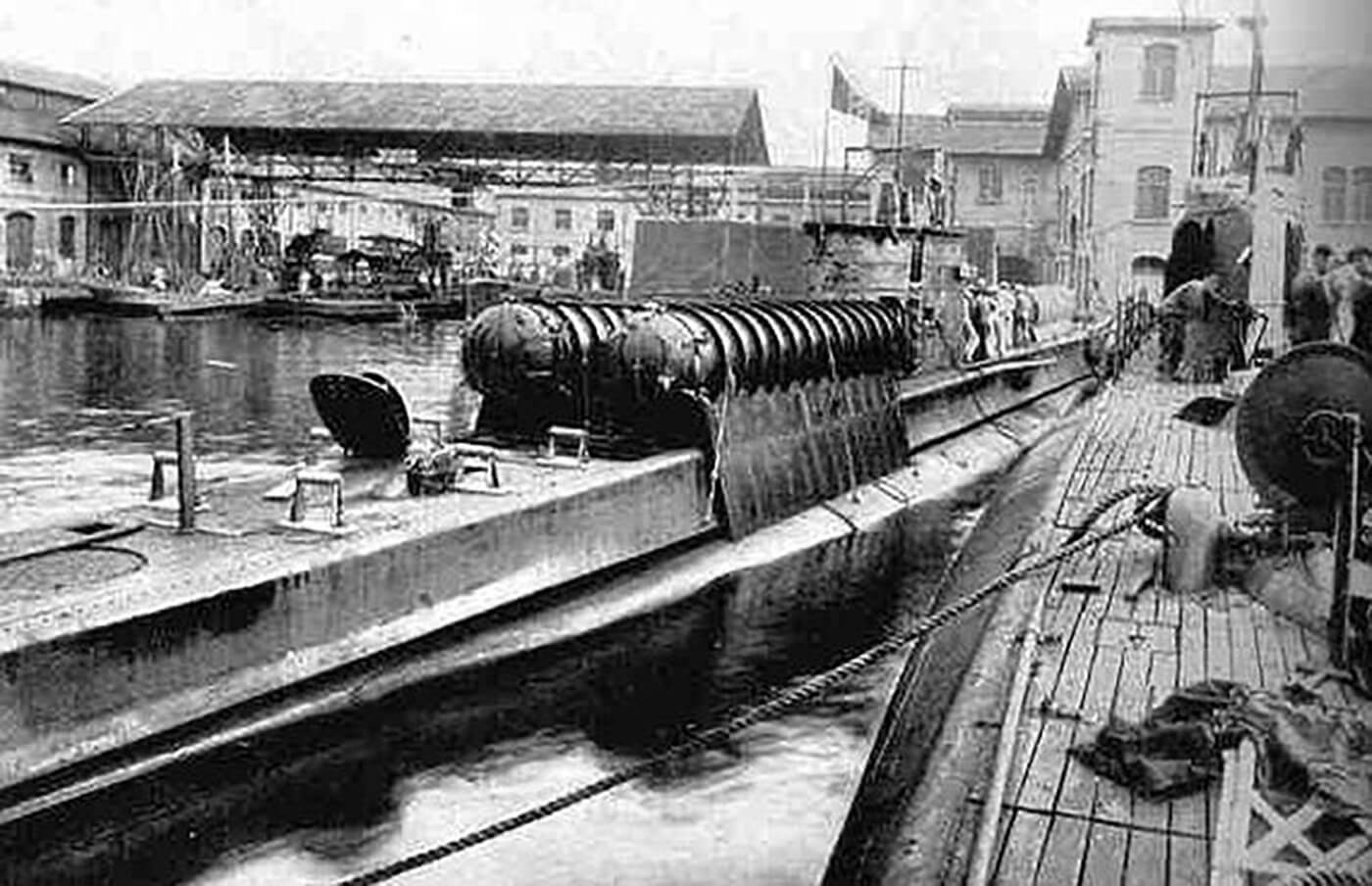

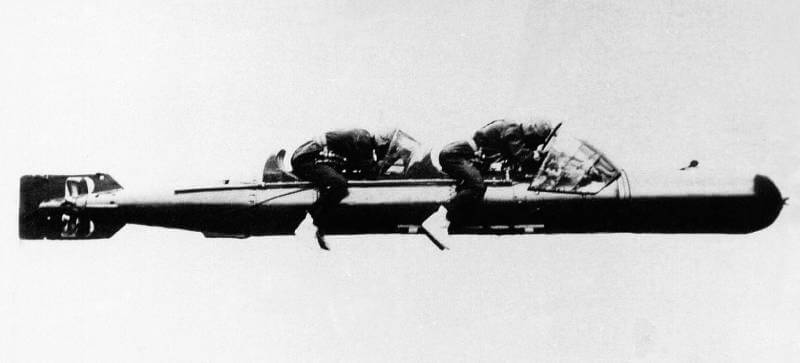

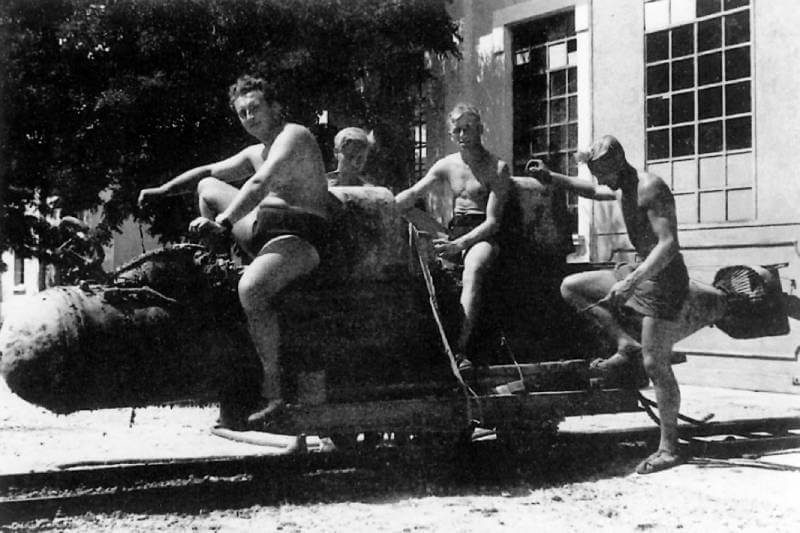

Designed for two operators, the craft is steered in a manner akin to riding horseback. The crew wear wetsuits and employ advanced scuba equipment produced by specialist manufacturers, facilitating extended underwater operations. Production is carried out in multiple series by the Officina Siluri San Bartolomeo at the La Spezia Dockyard.

Following an initial proposal, the Regia Marina sees potential in the project, prompting a thorough review by the Naval Staff. The response is positive, and in early October 1935, the San Bartolomeo Torpedo Workshop at La Spezia is discreetly instructed to construct a prototype. The design process prioritises using existing materials from the shipyard to maintain secrecy and reduce costs. By the time the first prototype (Device No 1) nears completion, a second (Device No 2) is already approved.

Device No 1 undergoes initial trim tests in a shipyard basin on October 26th, 1935, observed by Admiral Mario Falangola. Encouraged by the results, Falangola orders the construction of additional units. By 2 November, the craft is ready for sea trials, yielding modest yet promising results. Device No 2, trialled on January 6th, 1936, highlights several deficiencies but benefits from lessons learned with Device No 1. It returns for further testing on May 28th, 1936, by which time the Naval Staff orders four additional units under the cover name ‘self-propelled mines’. Construction remains at the San Bartolomeo workshops, now under the supervision of La Spezia’s Underwater Arms Department.

Despite progress, interest in the project wanes after the Ethiopian campaign concludes in May 1936. As the likelihood of imminent confrontation with the Royal Navy diminishes, so does the urgency to complete the Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s. By August 1936, personnel training slows before ultimately halting. Operators are reassigned to conventional roles but sworn to secrecy regarding their involvement.

The concept resurfaces in June 1937, when the Naval Staff orders an update of the two prototypes and proposes constructing six more units. In 1939, the Siluro a Lenta Corsa training programme relocates to a concealed facility at Bocca di Serchio, where intensive testing and refinements continue. By August 18th, 1939, reports indicate eleven Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s in existence, though only Devices No 9 and 10 are service-ready. Modifications continue, particularly to Device No 8, to enhance speed, stability, and buoyancy.

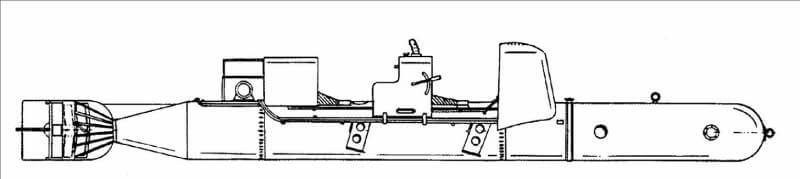

Commander Paolo Aloisi, leading the 1a Flottiglia MAS, enlists engineer Guido Cattaneo from Milan’s CABI to refine the Siluro a Lenta Corsa design. Project Trespolo sees significant changes to propulsion and trim systems, extending the craft’s length to 7.3 metres and increasing motor power to 1.6 hp. By July 1940, as Italy enters the war, an order is placed for a further eight improved units, designated Series 100, followed by Series 200 in early 1941.

By the end of 1940, Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s from the initial production batches are used in various missions in Alexandria. Series 100 craft are employed in actions at Gibraltar in May 1941 and Malta in July 1941. By December 1941, one Series 100 and two Series 200 Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s play key roles in the attack on Alexandria. Subsequent missions utilise Series 200 craft, some fitted with dual explosive charges.

Between 1935 and the armistice, it is believed that no more than 45 to 50 Siluro a Lenta Corsa (including prototypes) were constructed. The initial eleven craft consisted of two prototypes completed between 1935 and 1936, followed by a batch of four ordered in April 1936 and a subsequent five commissioned in 1939. These units were sequentially numbered from 1 to 11. In the summer of 1940, an additional series, likely comprising eight improved Siluro a Lenta Corsa, was ordered and designated within the ‘100’ series. This resulted in the 12th to 19th units being marked as 120, 130, 140, and so forth, reflecting a zero added to the sequence.

Craft produced after early 1941 appear to follow a numbering system within the ‘200’ series, beginning with the 20th unit and ascending with the prefix 2, resulting in numbers such as 220 and 221. The highest confirmed serial number is 236, completed in December 1942. This likely indicates the 36th craft constructed, suggesting that from autumn 1942 to September 1943, around fifteen additional units were manufactured.

An anomaly exists with Siluro a Lenta Corsa 210, which was deployed and lost off Gibraltar in September 1941. Its numbering does not align with the typical sequence, as it likely should have been recorded as 221 if it were the 21st unit produced. This discrepancy suggests that 210 may have been an earlier 100 series craft, modernised to match the 200 series specifications, necessitating a change in designation.

| Specifications |

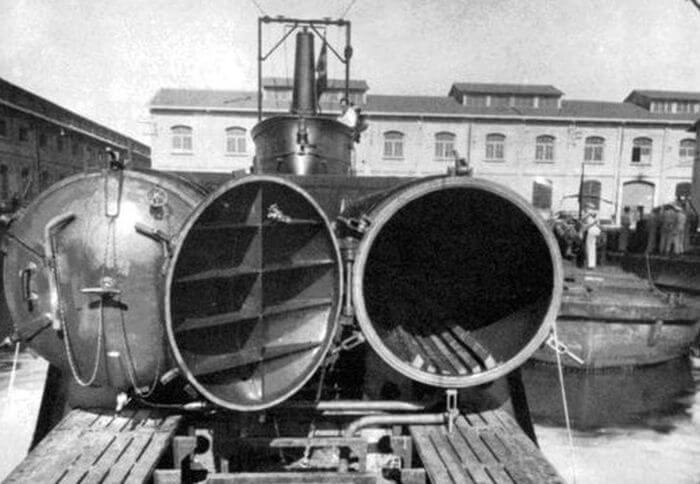

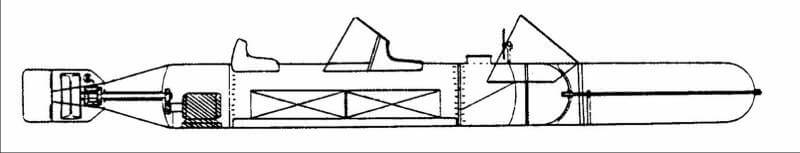

Early Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s are constructed using salvaged materials. Components such as the head, body, and tail originate from modified 533 millemetres submarine torpedoes. Transmission systems are re-engineered to replace traditional propulsion with electric motors, progressively increasing from 1.1 to 1.6 hp. Propellers transition from dual counter-rotating models to larger three- or four-bladed single designs, measuring approximately 38.5 centimetres.

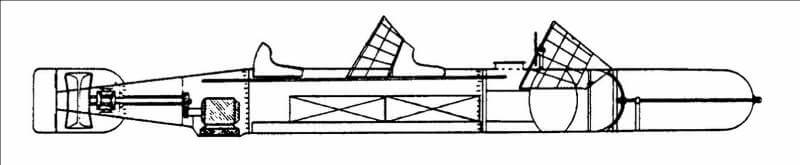

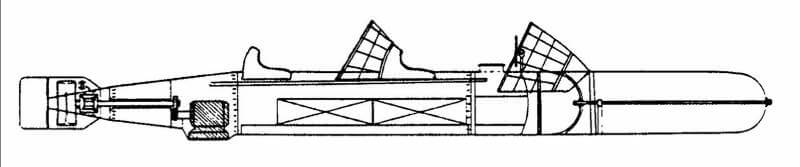

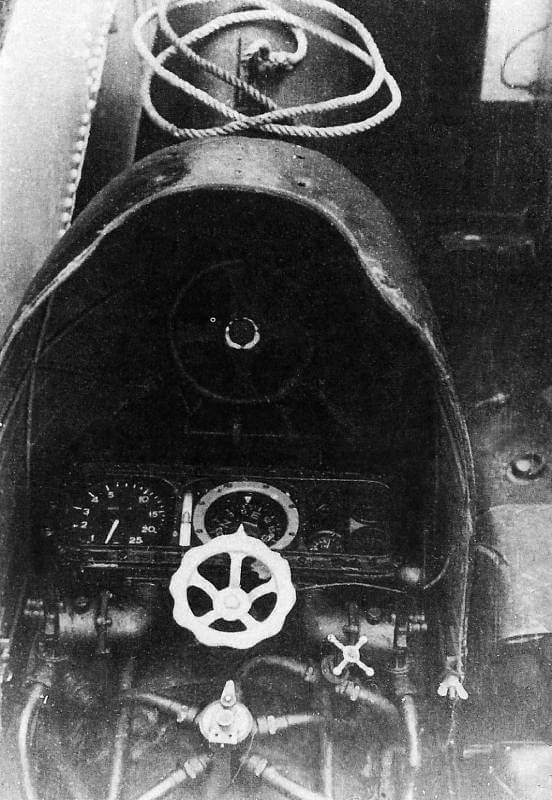

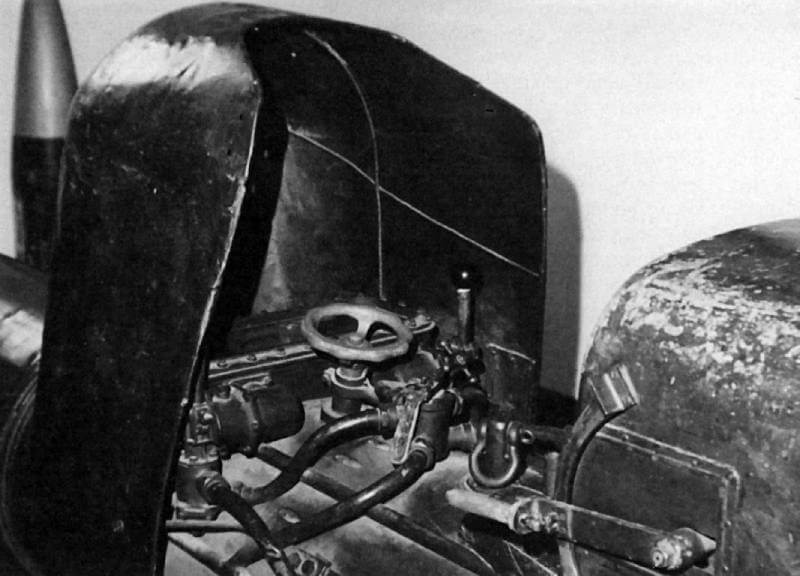

The Siluro a Lenta Corsa measures 7.3 metres in length, weighs around 1,400 kilograms, and features a cylindrical body 0.53 metres in diameter. The pilots, seated in tandem, initially straddle the craft without foot supports, which are later introduced to reduce fatigue. The vessel consists of five distinct sections: the head containing the explosive charge, the manoeuvring head with control mechanisms, the central body housing the batteries, the tail with the engine, and the structure featuring rudders and propellers. Trim tanks are integrated and can be emptied using two electric pumps. The torpedo head, designed to hold an explosive charge of approximately 300 kilograms (with the casing alone weighing 68 kilograms), undergoes modifications to include Borletti clockwork fuses from Milan. It can detach from the central body through a connecting band, later substituted by a longitudinal pin. The detachable warhead, is affixed to the target’s hull using cables and clamps. Operators manually detach the warhead and set timers before withdrawing.

A suspension eyebolt enables the explosive head to be suspended beneath the target vessel using a cable. The forward trim tank and manoeuvring controls are situated in the manoeuvring head. The central body, sealed by watertight bulkheads at both ends, contains 30 elements of a 150 Ah – 60 V battery. The tail houses the 1.1 HP engine, later upgraded to 1.6 HP. This allows a submerged speed of 3 knots and a range of approximately 28 kilometres at 2.3 knots. On the surface, the speed remains similar, but piloting the craft awash conserves oxygen for the operators. The aft trim tank, crossed by the propeller shaft, is also located in this section.

A speed reducer and thrust bearing link the engine to two counter-rotating axial propellers. The reducer, frequently prone to malfunctions, is later replaced by a single, four-bladed propeller that proves more efficient at lower speeds. A conical cage encases the propeller to prevent entanglement with nets or cables. Vertical and horizontal rudders are controlled through an intricate system of transmissions, pulleys, and cables.

The two operators straddle the torpedo, seated on metal brackets. The pilot, positioned at the front, is shielded by a protective cover that also houses a watertight instrument panel equipped with a depth gauge, clock, compass, voltmeter, two ammeters, and a spirit level. Speed adjustments are made via a rheostat, and the vessel is fitted with reverse gear. Directly behind the pilot sits the quick-release tank and 200 atm compressed air cylinders. The relief valve is controlled by a lever on the left side of the tank.

Behind the second operator’s seat, a block of balsa wood provides buoyancy to counterbalance the engine’s weight. Positioned above the tail is the final external feature, known as the tools bonnet, measuring approximately 1.10 metres in length. This lightweight structure, made from angle-irons, allows for free circulation and houses specialised equipment. The bonnet contains essential tools including:

- The net riser, initially a small tackle made from cables and blocks, is used to lift the slack of underwater nets, allowing the craft to pass beneath. This is later replaced by a more effective compressed air device designed and produced by CABI.

- The net cutter begins as a large hand-operated shear with wooden handles but is later upgraded to a compressed air-powered tool, also developed by CABI.

- Clamps are large screw fastenings used to secure the warhead suspension cable to the bilge keels of target vessels.

- The elevator, a simple cable originally wound on a wooden board and later on a reel, is fixed to the craft and unspooled by an operator. This helps locate the craft on the seabed in complete darkness after disembarkation.

- Reserve breathing apparatus with limited endurance compared to the standard units used by the operators.

- Small watertight containers (including a food container tube).

At the rear of the tail, the craft features a frame that includes a conical guard designed to protect the propeller or propellers from entanglement in nets or cables. Positioned behind the propeller, the vertical and horizontal rudders are connected to their control mechanisms through a pulley-operated tiller wire system.

For lifting during launch and recovery, two large eyebolts are welded to the upper section of the central body near the operators’ seating area. These attach to the steel cable sling via shackles. Each craft is also believed to be fitted with self-destruct charges equipped with time fuses, operated by the crew.

| Breathing Apparatus |

The oxygen system must provide sufficient air during the submerged approach and while attaching the explosive charge to the target. Interestingly, the breathing apparatus officially adopted by the Royal Navy, as described by Dr. Ferdinando Dorello in his 1938 manual, differs from the version used by Italian assault craft operators, likely to maintain secrecy over strategic equipment.

To address these issues, a commission is formed in January 1935. It includes Major Doctor Ferdinando Dorello, Frigate Captain Catalano Gonzaga di Cirella, and Commander Mario Moschini. The commission outlines essential specifications for the companies tasked with developing the apparatus. By early 1936, the first advanced prototype is completed by IAC (Industria Articoli Caoutchouc), a Tivoli-based company specialising in gas masks and underwater equipment. This division is led by Commander Angelo Belloni, a renowned inventor of diving gear.

The initial breathing apparatus, inspired by the Davis rebreather, features a sturdy frame and an anatomical rubber mask with dual eyepieces, which later becomes an iconic symbol of Italy’s combat divers. Designated as Modello 49, around thirty units are produced and used in the early training phases of SLC operators. Subsequent refinements lead to the development of Modello 49/bis, which is later adopted by the Xª MAS Flotilla and naval divers. This version eliminates the lateral overpressure valve, enabling divers to release excess oxygen by loosening their grip on the mouthpiece, and extends operational autonomy to five hours.

In addition to the long-range apparatus, a smaller, short-autonomy version is produced, offering reduced bulk for specialised missions. Throughout the war, further breathing apparatus are manufactured by Pirelli and Salvas for both Siluro a Lenta Corsa operators and Gamma divers, contributing to the versatility and effectiveness of Italy’s underwater assault forces.

| Tactics |

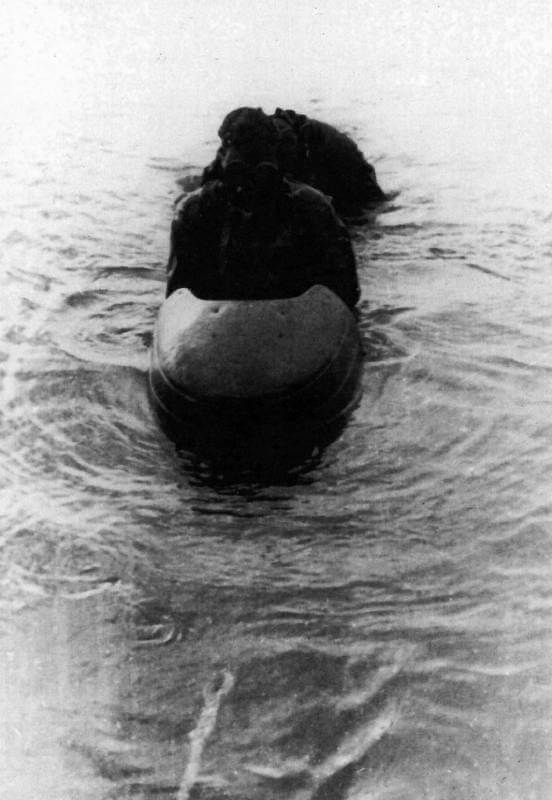

Under the cover of darkness, the Siluro a Lenta Corsa and its operators are typically deployed near the target from either a surface vessel or a submerged submarine, known as the approacher. Alternatively, operations may begin directly from forward bases such as the Olterra at Algeciras.

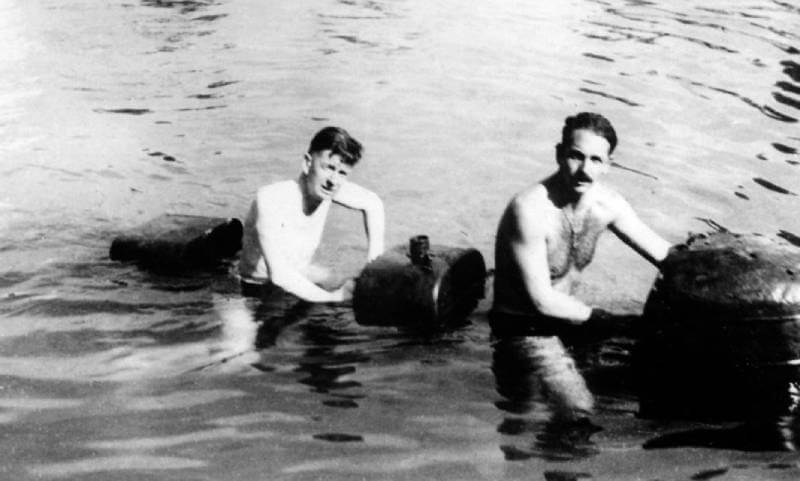

Upon extraction from the container cylinder, sometimes with the assistance of reserve operators if launched from a submarine, or lowered into the water from a surface ship, the operators adjust the trim and balance by redistributing liquid ballast. The craft’s buoyancy is carefully monitored, as water temperature and salinity, especially near estuaries, can cause natural variations.

This process is conducted swiftly and silently. The final approach to the target begins on the surface, as the operators conserve the limited oxygen supply of their breathing apparatus.

When surface navigation is unsafe, due to moonlight, phosphorescence, or increased enemy vigilance, the operators switch to submerged navigation. The craft proceeds at ‘glasses depth,’ with the forward operator’s head barely above water. In some cases, the breakwater remains visible. The second operator remains fully submerged, necessitating continuous use of the breathing apparatus.

Stealth is critical. Operators must avoid detection by enemy patrols and defences, which have increased in response to previous Siluro a Lenta Corsa missions. Following early attacks, enemy forces resort to dropping small underwater charges at random intervals to counter this threat.

As the Siluro a Lenta Corsa nears the target, sometimes within mere metres, the operators open the ballast tank valves, carefully avoiding noisy air bubble release. The craft descends and continues its approach guided by compass bearings taken during the final surface observation by the first operator.

Harbour defences or net obstructions often guard the target vessel. If surface passage is impossible, the Siluro a Lenta Corsa dives to the seabed, creeping forward to identify gaps. When necessary, the operators deploy the ‘net riser’ to lift the barrier by securing the upper tackle to the net and the lower hook to the seabed. By hauling on the line, the operators create just enough clearance to slip beneath.

This procedure, while simple, demands precision and is performed in complete darkness. British forces, adapting to these incursions, respond by extending net depths to prevent such lifts, making the net riser ineffective. When faced with these deeper nets, operators resort to cutting tools to shear through cables, taking care to avoid triggering any alarm wires integrated into the nets.

Once past the defences, the Siluro a Lenta Corsa navigates the final stretch towards the target ship. The craft moves in brief dives, occasionally surfacing to confirm bearings or sending the second operator to observe using the ‘elevator’ cable. Noise from the target’s machinery can further aid navigation.

Upon reaching the ship, the operators manoeuvre beneath the hull, targeting the bilge keels. The second operator secures a clamp and cable to one bilge keel, guiding the Siluro a Lenta Corsa under the keel to the opposite side, where another clamp is attached. By manually hauling the cable, they position the craft centrally beneath the hull.

The second operator connects a rope from the warhead’s eyebolt to the cable, securing the explosive in place. After loosening the strap or pin, the Siluro a Lenta Corsa detaches from the warhead, leaving it suspended beneath the target. A counter-clockwise turn of a knob activates the detonator, setting a timed fuse to allow the operators to retreat or destroy the craft if necessary.

| Operational Use |

The Siluro a Lenta Corsa achieves its most notable success on December 19th, 1941, when the X MAS Flotilla conducts a raid on Alexandria. Three Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s, launched from the submarine Sciré, penetrate the harbour and successfully damage the British battleships H.M.S. Valiant and HMS Queen Elizabeth, along with a tanker and a destroyer. The Italians also employ the merchant vessel Olterra, interned in Algeciras, as a forward base for operations in Gibraltar. Components of the Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s are smuggled in pieces and reassembled aboard the Olterra.

| Multimedia |

| Versions |

| Italian Use |

| Siluro a Lenta Corsa tested by the Allied |

| Support Craft |