| Length |

| Wide |

| Height |

| Weight |

| Propulsion |

| Electric |

| Armour |

| – |

| Armament |

| – |

| History |

In 1942, the Combined Operations Command (CCO) tasks the Inter-Service Research Bureau (ISRB) to create a device that assists underwater swimmers in operations against enemy shipping and harbours, suitable for transportation to the operation site in a two-man canoe. Unfortunately, the device, known as the Welbum, proves impractical due to significant drag, and it is confused post-war with the “Underwater Glider” in military documents.

Hugh Quentin Alleyne Reeves command the Inter-Service Research Bureau. He attends Cambridge University where he graduates in 1931 with a Second-Class bachelor’s degree in engineering. Before his commission into the Royal Army Service Corps, he serves as a joint Managing Director for a firm of Consulting Engineers, involved in boiler and electrical generating plant and water services. Seconded from the War Office to the Inter-Service Research Bureau, Major Reeves, is stationed at Station IX. Known for his quiet and analytical nature, and as a man of detail, Reeves later becomes the Commanding Officer of Inter-Service Research Bureau Station VIII at Staines. Here, Major Reeves proposes an alternative: a highly manoeuvrable, electrically propelled, one-man submersible canoe that can be transported on a Motor Torpedo Boat deck or inside a submarine’s pressure hull. This proposal is initially rejected by the Admiralty’s Department of Naval Construction due to concerns about stability during submersion. Undeterred, Maj. Reeves successfully advocates for his design, which leads to the prototype being built and tested at Inter-Service Research Bureau’s Frythe workshops.

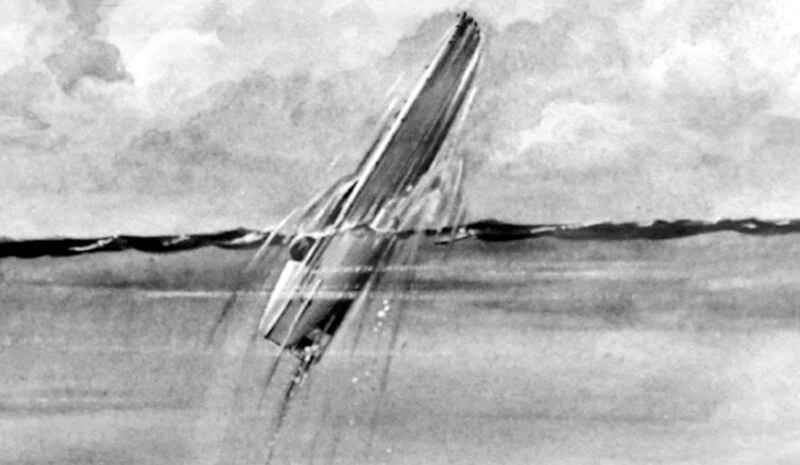

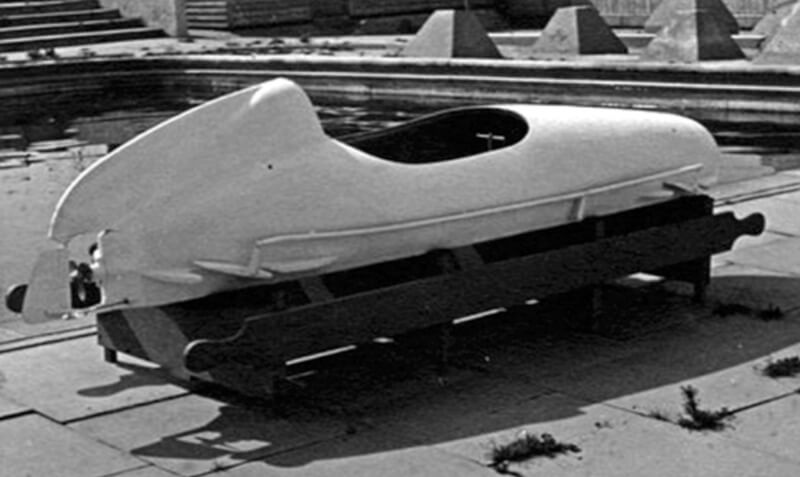

The prototype, initially named the Underwater Glider, undergoes trials in 1942. By April 1943, it demonstrates good stability and handling with an estimated range of approximately 10 kilometres at a surface speed of about 4.6 km/h with the pilot’s head above water, or 5.6 kilometres/hour when fully submerged. Despite these successes, comprehensive underwater trials are not conducted due to concerns about insufficient hydroplane area.

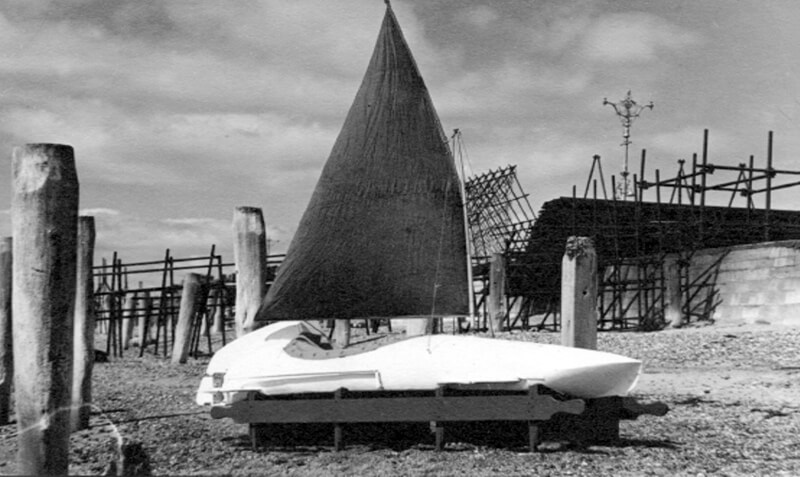

The Underwater Glider Mark I is satisfactorily tested by May 29th, 1943. It features hydroplanes at both ends with exterior connecting rods. Launched from a beach cradle into the Solent, it undergoes trials for motorised movement and paddling. However, most records and photographs from these trials obscure its identity as the Underwater Glider, with few showing it with sail and canopy rigging.

Further tests at the Admiralty Experimental Works and field trials at Southsea by the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment and Saint Albans indicate a promising future for this craft, leading Prof. Newitt to endorse the design to Colonel R.H. Barry. The craft’s primary function is attacking enemy ships below the waterline, reconnaissance up to a depth of about 15 metres, and delivering correspondence to enemy-occupied shores.

| Underwater Glider Mark II |

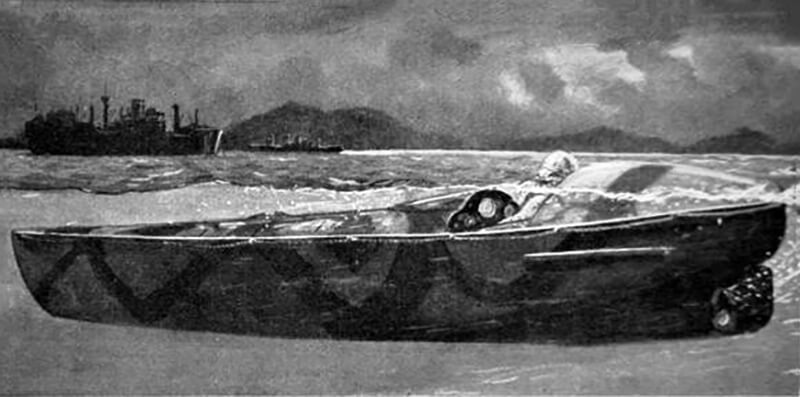

Major Reeves’s report in October 1943 describes the Underwater Glider Mark II, detailing transport, operation, and training for underwater operation. The craft is a steel-built single-seater canoe, about four metres long with a beam of sixty-nine centimetres, capable of carrying neutrally buoyant charges weighing up to about twenty-seven kilograms. It can travel on the surface with only the pilot’s head showing or fully submerged, propelled by sail, paddles, or an electric motor. The Underwater Glider is also manoeuvrable by hand for short distances or to turn around, illustrating its versatility and strategic utility in covert operations.

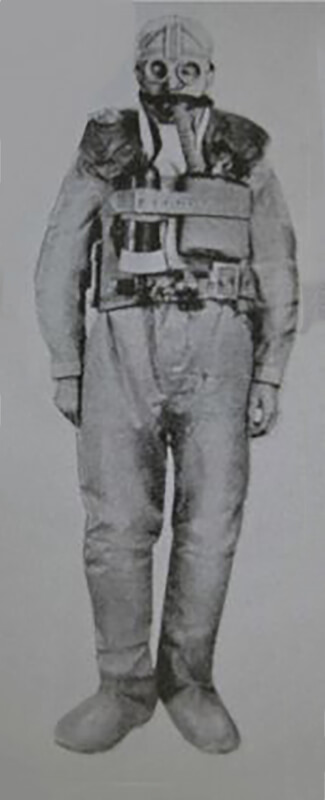

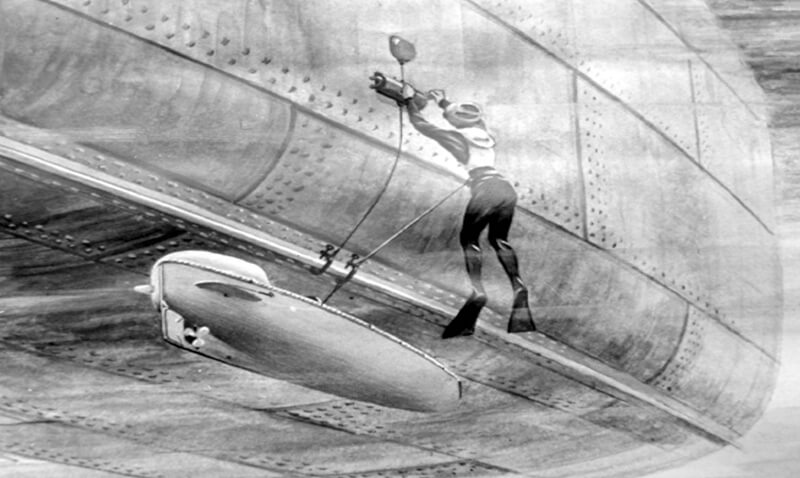

At that time, the canoe pilot wears a lightweight rubber suit and carries onboard oxygen breathing gear, which he dons before submerging. The standard breathing setup provides the pilot with one hour of oxygen underwater, with an auxiliary system on the craft offering an additional hour’s supply. The operator can also wear swim fins, allowing for easy entry and exit from the craft.

Training for underwater operation is considered straightforward, necessitating only ten minutes of instruction on land, provided the operator is fully trained in using the oxygen breathing apparatus. The craft is controlled via a single stick that manages both the rudder and hydroplanes, which is simple to operate and exhibits no problematic characteristics. To ascend or descend, the pilot merely pulls or pushes the stick, respectively.

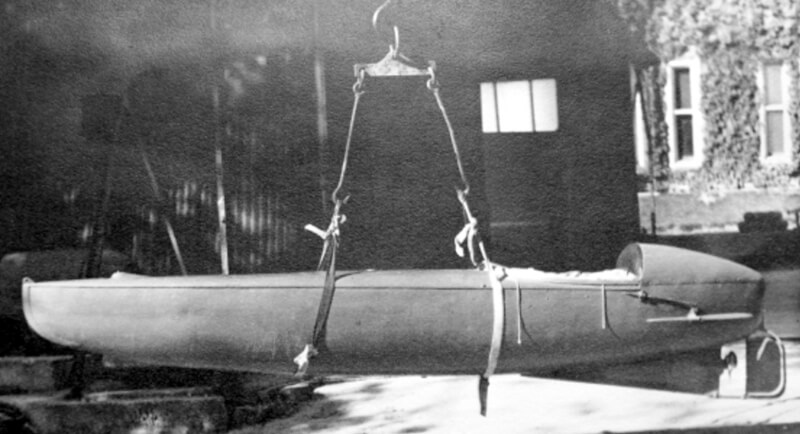

The Underwater Glider weighs between 250-272 kilograms and is transportable on a motor cutter, Motor Torpedo Boat, or Welfreighter; it can also be airdropped, although this has not been achieved by October 1943. The vessel is launched from the parent craft, either from rollers in the case of the motor cutter or by being lowered by slings in the case of the Motor Torpedo Boats, typically released 8-16 kilometres from the target.

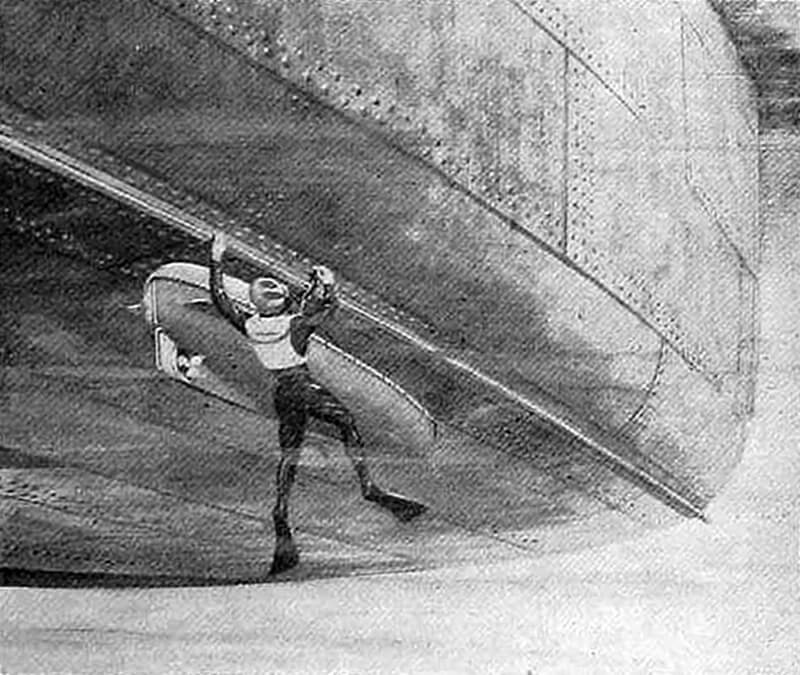

In the trimmed-down position, barring movement through a narrow channel heavily guarded by sentries, the operator may opt to travel at a shallow depth of 3-4.5 metres below the surface. The final approach is usually undertaken 55-91 metres underwater, at slow speed. The target is located by bumping, followed by brief reconnaissance before the charges are placed. Once back at the 30-metre mark, eye-level buoyancy is achievable.

After navigating through defences and channels to open sea, the operator can surface fully on tanks by expelling water from the craft using the keel’s ejection gear, which leverages the propeller’s suction, supplemented by a hand pump below the dashboard. The operator then removes the breathing apparatus and can proceed along the surface as an electric canoe, aided by sail if necessary, to rendezvous with the parent craft.

| Trials |

As of October 1943, the Motorised Submersible Canoe Mark II is under rigorous testing overseen by the Combined Operations Headquarters. The trials, occurring in Southsea, feature Sub Lieutenant Riggs of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve and Major Hasler of the Royal Marines. They conduct a series of detailed manoeuvres to assess the operational capabilities and endurance of the craft.

Despite challenges such as adverse tides and frequent engine failures requiring assistance from an attendant dinghy, the craft covers an estimated distance of 38.8 kilometres. After an electric switch malfunctions, a replacement is installed, allowing further tests. Major Reeves subsequently takes command, and the craft performs satisfactorily through various power dives and handling tests.

In response to the promising trial outcomes, a strategic decision is made to escalate production. Plans are underway to construct six additional units of the Motorised Submersible Canoe Mark II at an estimated cost of £5,000 each. However, the Inter-Service Research Bureau Station faces production constraints, prompting discussions about outsourcing part of the production to Fairmile Marine Co. Ltd.

The craft demonstrates robustness and adaptability in naval operations, managing long distances at cruising speeds under various conditions, including tests from Southsea to Cowes Roads and beyond. These trials not only confirm the craft’s physical capabilities but also its strategic utility for covert operations near enemy lines.

Endurance trials further validate the operational viability of the Motorised Submersible Canoe Mark II, with the craft proving capable of sustained long durations at sea, covering significant distances, and maintaining stability and speed. These trials involve multiple pilots and rigorous testing regimes, underscoring the craft’s potential to enhance naval stealth and attack capabilities.

By December 1943, official specifications and further development plans for the Motorised Submersible Canoe Mark II are established, marking significant advancements in the design and functionality of submersible craft for combat purposes. The refined specifications and operational parameters are confirmed by Admiral Taylor, setting the stage for broader deployment and integration into naval operations.

The craft is engineered to endure pressures equivalent to 18 metres of water depth, with its individual tanks rigorously tested to exceed this specification.

As early as December 6th, 1943, preliminary considerations are in place for a two-seater version of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’. The envisaged specifications for this craft are that it measures approximately 6.7 metres in length with a beam of eighty-four centimetres, and a weight of about 771 kilograms, inclusive of the charge. The total weight of the container and explosives, designed to be neutrally buoyant, stands at approximately 181 kilograms. The cruising speed is targeted to not fall below 5.5 kilometres/hour, ideally approaching 6.5 kilometres/hour, with a maximum speed of about ten kilometres/hour. The range is expected to reach eighty kilometres at surface cruising speed. The craft is to be powered by a 2 horse power, 60 Volt electric motor, with power supplied by a bank of 60 Volt nickel-iron accumulators, providing an approximate capacity of 120 ampere-hours at 60 Volts.

The primary use and specifications remain fundamentally the same as those of the single-seat version and similarly mirror those of a “Chariot”, featuring the designed capability to attach the charge to the target via bilge keel clamps and by manipulating buoyancy. A distinctive feature of this two-seater variant is its method of delivery, which includes being carried, attached to the keel of fishing or cargo boats.

In early December 1943, Commander Sims from the Department of Naval Construction at Bath and Major Reeves review the complexities involved in contracting out three additional Motorised Submersible Canoes. Reeves informs Sims that the trio of crafts under production at The Frythe incorporates several modifications from the original prototype and anticipates the first will be trial-ready by month’s end. At this point, a complete set of blueprints is unavailable, though they possess drawings for various components.

Colonel Dolphin suggests that Sims, along with a representative from Fairmile and a draughtsman, should visit Station IX on December 8th, 1943, to discuss the craft and its drawings to ascertain what further details Fairmile requires. Reeves considers the production process straightforward, despite the need for skilled panel beating in manufacturing the hull and battery tank, which would be facilitated using press tools.

The meeting on 8th December 1943 at The Frythe is attended by Admiral Taylor, Lieutenant Commander C.E. Nisbet of the Royal Navy (Admiralty Miscellaneous Weapons), Colonel Dolphin, Major Reeves (Inter-Service Research Bureau Station), and representatives from Fairmile, the Department of Naval Construction, and Department of Electrical Engineers. It is agreed that Inter-Service Research Bureau Station will provide Fairmile with two sets of all available blueprints along with a materials specification, samples of turned parts, contractor details, and order information. The Department of Naval Construction will also receive all relevant data affecting propeller design, and Inter-Service Research Bureau Station will liaise with Siebe Gorman about the cockpit hood, enabling Fairmile to place a direct order.

It is noted that during the fitting out of production hulls from Briggs bodies by Fairmile, all authority for production modifications remains with Reeves, who positions two inspectors at Fairmile, one civilian and one a Royal Engineers Captain. Department of Electrical Engineers is tasked with supplying motors and batteries, while the Admiralty Miscellaneous Weapons and DCD provide diving suits and compasses, respectively. This comprehensive information is necessary for Fairmile to quote for the three pending ‘Sleeping Beauties’. By December 13th, 1943, Royal Marine Boom Patro Detachment is preparing to expand its establishment to four teams, each comprising one officer and three sergeants, supported by sufficient maintenance staff, and is also considering a training base on the northwest coast of Scotland.

The ‘Sleeping Beauty’ is somewhat untested but seen as highly promising, especially if it can be produced timely for Operation Overlord. Despite the Force Commander for Operation Overlord being unaware of its existence, it is expected that he will be informed once an order is placed.

By the end of December 1943, it is clear that the submersible single-seater canoe known as Motorised Submersible Canoe will either carry one anti-capital ship charge or several type A & B underwater swimming charges, then being produced by SMD for the Chief of Combined Operations, designed for easy detachment during transport.

Just before Christmas 1943, the board approves building three more crafts by Fairmile. Commander Sims and Major Reeves discuss drag issues, aiming for a top speed of 8.34 km/h and half-speed of 5.56 km/h using a 21.6 cm propeller. By December 1943, the Motorised Submersible Canoe Mark II shows improved speeds of 6.30 km/h cruising and 8.40 km/h top speed. Construction and testing go smoothly, and further tests are planned. Major Reeves remains optimistic due to positive feedback. The crew prepares for training with new equipment.

From May 8th, 1944, to May 10th, 1944, an exercise at Loch Corrie and Linnhe, Oban, showcases the canoe’s capabilities. Despite cold water, the exercise, led by Major J. D. Stewart, by then the Commanding Officer of the Royal Marine Boom Patrol detachment, proceeds with successful day and night drills, demonstrating the craft’s effectiveness in stealth and attack. The service ship H.M.S. Quentin Roosevelt, commanded by Lieutenant Dingwall, serves as the target vessel for drills conducted both day and night. The exercise concludes successfully with the simulated destruction of the target ship, demonstrating the craft’s stealth and attack effectiveness.

Throughout 1945, the Motorised Submersible Canoe is integral to several operations, including trials with “S” class submarines, demonstrating their utility in attacking targets in shallow waters. Despite the formal renaming to Motorised Submersible Canoe, operational communications frequently revert to the original name, underscoring a persistent preference for the initial nomenclature. Further developments in design continue into post-war, highlighting ongoing improvements and adaptations to enhance operational efficiency and range, marking the Motorised Submersible Canoe not just as a wartime expedient but a significant advancement in naval submersible technology.

| Specifications |

The primary function of the Motorised Submersible Canoe is to deliver an underwater swimmer and multiple anti-ship charges to a target. The swimmer could either deploy the charges independently after exiting the submersible or operate directly from the submerged craft. Charges could be set while the craft is fully flooded, rendering both swimmer and craft completely submerged, or in a trimmed-down position with the driver’s head above water. Equipped with a lightweight diving suit, fins, and an oxygen apparatus, the swimmer can operate underwater for approximately forty-five minutes, depending on depth and exertion levels. Under full power, the craft achieves a range of approximately 65-74 kilometres at cruising speed in still conditions, and over 55 kilometres in open sea with winds up to Force 5.

Designed for extreme seaworthiness, the Motorised Submersible Canoe maintains positive stability in all conditions, whether flooded or not, and shows no propensity to capsize even in rough seas. The craft can navigate through waves and, if fully flooded, remains buoyant and can be pumped dry via a bilge pump located at the front left of the pilot. Structurally, it is engineered to withstand depths up to approximately fifteen metres and is easy to dive, controlled mainly by hydroplanes once in diving trim. The swimmer can easily enter and exit the submerged craft, and surfacing is achieved by blowing the tanks with air bottles. The pilot, seated comfortably, can operate the craft for extended periods without fatigue, benefiting from adjustable seat heights.

The craft’s stealth is enhanced by its minimal surface silhouette and high cruising speed, with an almost invisible bow wave and a silent motor. In a trimmed-down state, only the pilot’s head is visible, and in fully submerged conditions, the pilot is entirely out of sight. However, the craft’s weight makes onshore handling by the pilot impractical. The maximum payload excluding the swimmer is approximately 27 kilograms, suitable primarily for carrying charges intended for static, unarmoured ships.

The Motorised Submersible Canoe can be transported through a submarine’s torpedo hatch and carried on specially modified 7.6-meter motorboats, which can be hoisted on a destroyer’s davits. The potential for parachute deployment via seaplane is under exploration at that time. In late November to early December 1944, three submersibles are tested for resistance at the Vickers-Armstrong testing tank in Saint Albans, where it humorously emerges that official communications still refer to the craft as ‘Sleeping Beauty’ rather than its designated Motorised Submersible Canoe, reflecting a light-hearted disregard for stringent nomenclature rules.

The diverse configurations of the three crafts, identified by the letters A, B, and C, include variations in rudder design and motor housing, demonstrating the evolving design and production scale of the Motorised Submersible Canoe. The inclusion of these craft in the Admiralty’s numbering system highlights their ongoing role in testing and operational refinement.

| Multimedia |

| Conceptual and Instruction Art |

| Indoor Testing |

| Outdoor Testing |

| Pilots |