| Length |

| 6.8 and 7.65 metres |

| Wide |

| 533 millimetres |

| Height |

| Weight |

| 1,500 kilograms |

| Propulsion |

| 2-horsepower, 60-volt DC electric motor |

| Armour |

| – |

| Armament |

| Detachable of 245 kilograms of TNT |

| History |

|

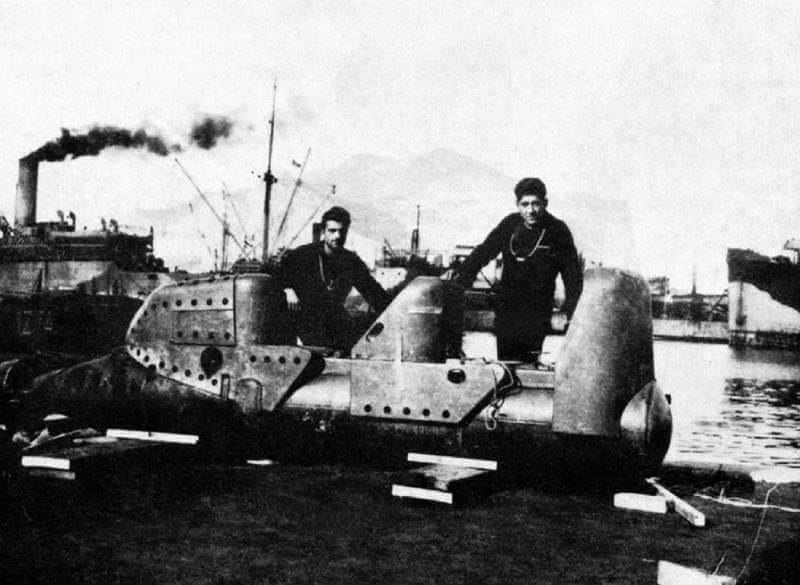

By the third month of the war, the Royal Navy begins to gather the first concrete intelligence on new submarine weapons designed to attack ships in harbours. Although broader information from intelligence sources may exist, little evidence confirms this. The first direct insight comes on September 30th, 1940, when aerial photographs capture the Italian submarine Gondar sinking off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt. The images clearly reveal three large, unfamiliar cylinders on the deck, evidently intended to carry special equipment. In addition to the standard crew of around forty-five under a Lieutenant’s command, British vessels rescue nine others, including a commander, four officers, and four petty officers, three of whom belong to the diver category. Among them is Capitano di Fregata Mario Giorgini, the head of the assault craft unit (then Sezione Armi Speciali) of the Xa Flottiglia MAS, along with six operators and two reserves designated for three manned torpedoes. This unusual discovery raises significant questions for the British.

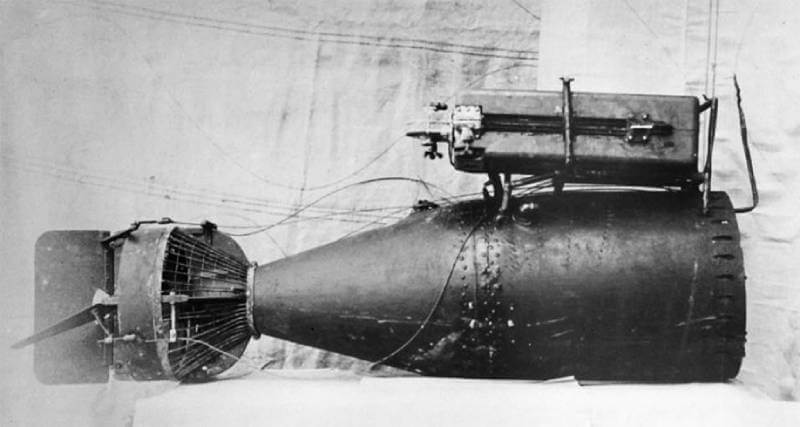

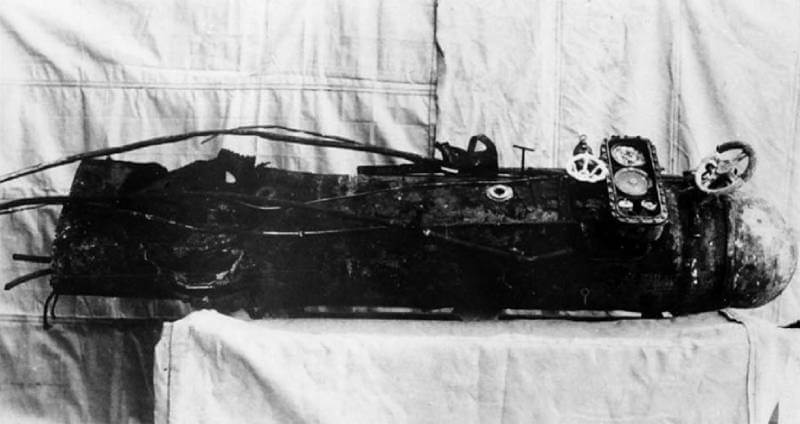

Further intelligence emerges following the failed Siluro a Lenta Corsa operation launched from the submarine Scirè in Gibraltar Harbour on October 29th, 1940. Italian commanders are well aware from the outset that there is a risk of the British discovering remnants of the manned torpedoes at the conclusion of missions. Despite self-destruct mechanisms and formal procedures for scuttling the Siluri a Lenta Corsa, it is inevitable that not all equipment is completely destroyed. During this operation, all three Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s suffer mechanical failures. One is recovered almost intact by the Spanish, while British divers locate the heavily damaged remains of a second at the bottom of the harbour. Two operators are also captured within the base after scuttling their torpedo, which sinks irreparably.

Although British efforts to persuade Spain to surrender the recovered craft are unsuccessful, it is likely that they manage to photograph significant details. These images, combined with wreckage and the gear of the captured operators, provide the British with a preliminary understanding of the ‘pigs’ and their operational methods. Interrogations yield further insights, although the Italian prisoners deliberately provide misleading information.

By July 1941, the British gain a clearer picture when they recover the wreck of one of the two Siluro a Lenta Corsa’s involved in the Malta attack. Despite being sabotaged and broken into three parts, the craft remains largely intact. Detailed examinations and technical drawings offer the British valuable intelligence on the characteristics of the torpedoes and the equipment used by their operators.

Following the remarkable success at Alexandria, the Royal Navy, driven by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, initiates the development of a similar craft known as the Chariot Mk I.

| Chariot |

On January 18th, 1942, Winston Churchill sends a directive to General Hastings Ismay, Secretary of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee, :

“Please report on what has been done to emulate the successes of the Italians in the port of Alexandria through similar methods. Is there some reason why we are incapable of the same kind of scientific aggressive action as demonstrated by the Italians?”

The Submarine Service is tasked with overseeing development, leveraging technical information on Italian Siluri a Lenta Corsa gathered since 1940. The formal development of the Chariot begins in April 1942 under the leadership of two officers from the Royal Navy’s submarine service: Commander Geoffrey Sladen DSO, DSC, and Lieutenant Commander William Fell. Initial crew training is conducted aboard the depot ship HMS Titania, first stationed at Gosport on England’s south coast.

As the project advances, operations shift to Scotland, utilizing several remote and secure locations. Training bases are established at Loch Erisort, designated as Port “HZD”; Loch a’ Choire, known as Port “HHX”; and Loch Cairnbawn, referred to as Port “HHZ.” Additional training is carried out from H.M.S. Bonaventure (F139), which operates in the same region. These facilities provide the isolated and protected environments required for testing and preparing crews for missions involving this groundbreaking human torpedo.

A prototype self-propelled model, closely resembling the Italian design, is constructed at the Gosport submarine base. Training commences alongside construction using a wooden, unpowered mock-up towed semi-submerged by a speedboat. Operators use modified Davis type self-contained breathing apparatus, and the mock-up evolves through various names, Kerry Mark II, Cassidy, and finally Chariot.

The breathing apparatus is a modified closed-circuit oxygen device with a lung bag on the chest and a tank initially worn underneath but later mounted on the back. Operators wear the Sladen suit, a watertight rubber outfit with a purge valve on the cap and a single-glass facemask secured by wing-nut screws.

The first prototype, nicknamed The Real One, is tested at sea in June 1942. The design, later officially named Chariot, is continually refined, though the Mk I models remain mechanically unreliable, mirroring the early Italian Siluri a Lenta Corsa’s. Training accelerates, and within three months, a few dozen operators are combat-ready. Early trials at Portsmouth lead to the relocation of the training base to Loch Cairnbawn in Scotland, where H.M.S. Titania, an old depot and support ship, is stationed. Despite improvements, technical issues with the craft, suits, and breathing apparatus persist.

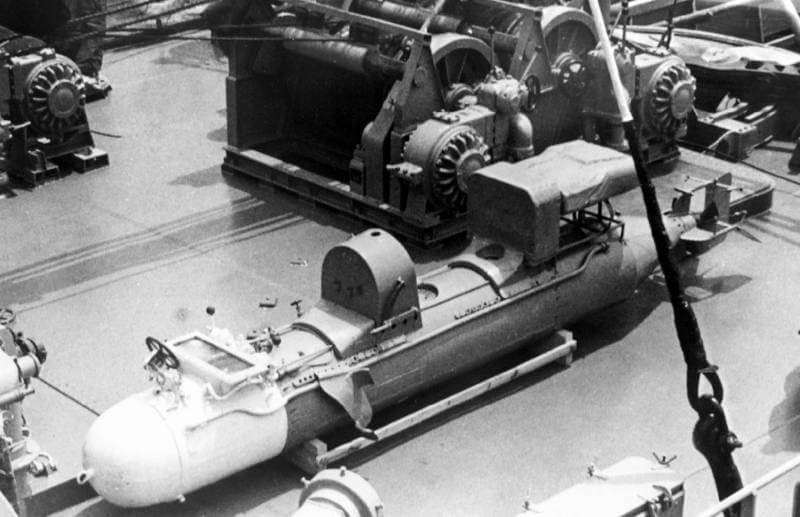

Towards the war’s end, the Chariot Mk II, known as the Terry Chariot, is introduced. Based on the Italian Siluro San Bartolomeo, this version features a back-to-back seating arrangement under a Perspex dome and is larger than the Mk I.

| Specifications Chariot Mk I |

The Chariot Mk. I weighs approximately 1,500 kilograms and measures between 6.8 and 7.65 metres in length. Its main body has a diameter of 533 millimetres. Propulsion is provided by a 2-horsepower, 60-volt DC electric motor, enabling a maximum speed of 2.9 knots. At this speed, the Chariot has a range of almost 30 kilometres or six hours of operation. It carries a detachable warhead containing 245 kilograms of TNT.

The electric motor is powered by a battery series with four forward and two reverse speed settings. The design adopts a combined joystick for steering and depth control, unlike the separate mechanisms on the Italian “pigs.” Italian operators later note that the Chariots are generally less reliable than late-series SLCs, suffering frequent propulsion failures. British wetsuits and breathing apparatus are also less effective, earning the “Sladen suit” the nickname “Clammy Death.”

| Specifications Chariot Mk II |

The Chariot Mark II is introduced in early 1944, featuring significant upgrades in size, performance, and firepower. Measuring 9.30 meters in length, 0.76 meters in diameter, and with a maximum height of 0.99 meters, the Mk. II weighs 2,400 kilograms. It achieves a maximum speed of 4.5 knots and can operate for 5 to 6 hours at full speed. Designed for a two-person crew, the operators sit back-to-back, ensuring efficient teamwork and control.

A major enhancement of the Mk. II is its warhead, which carries 540 kilograms of explosives, doubling the payload of the Mk. I and significantly increasing its destructive capability. In total, thirty Mk.II Chariots are produced during its operational period.

Visually, the Mk. II is easily distinguished from its predecessor. Unlike the Mk.I, where the crew is partially exposed, the Mk. II features a fully enclosed hull, with only the operators’ heads protruding, providing improved protection and a streamlined design for underwater operations.

| Transportation |

A Chariot’s limited range necessitates that it be transported close to its target before the crew can ride it under its own power to the objective. The warhead, which is activated by a timer, is detached and left against the enemy ship, after which the crew attempts to return to a prearranged rendezvous point with a friendly submarine. In cases where a rendezvous is not possible, the crew is forced to abandon the Chariot and escape by other means.

To avoid detection by German forces, unmanned Chariots are initially towed submerged beneath a vessel during part of their journey. However, in adverse weather conditions, both Chariots work loose from their securing mechanisms and are ultimately lost.

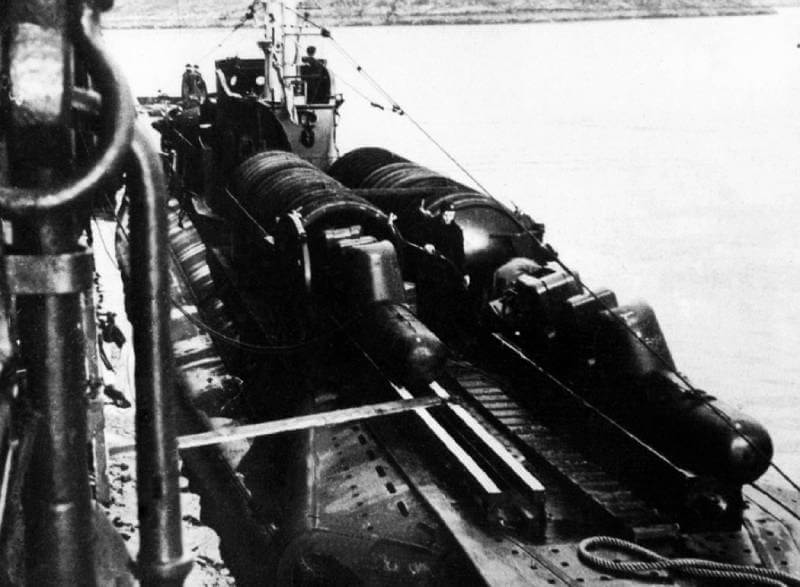

Later deployment involves transporting the Chariots to their departure points using submarines fitted with specialized containment tubes. These tubes, measuring 7.37 meters in length and 1.63 meters in external height, house the Chariots securely on wheeled bogeys, strapped down until ready for use. A total of ten tubes are constructed, with three installed on H.M.S. Trooper, two each on H.M.S. P311 and H.M.S. Thunderbolt, and one each on H.M.S. L23 and H.M.S. Saracen.

Later in the war, operational challenges with the tube system lead to a change in deployment strategy. Chariots are instead secured directly to the submarine’s deck using chocks, simplifying handling and improving reliability during transport.

| Operational Use |

The Chariot Mk I sees its first operational use in October 1942 against the German battleship Tirpitz in a Norwegian fjord. Transported via a fishing boat, the craft are lost en route due to unsafe conditions. Inspired by Italian techniques, the Royal Navy begins transporting Chariots using submarines equipped with waterproof cylinders, often mounted on T-class boats.

Operation Principal is launched in January 1943. It targets naval moorings in the Maddalena Islands (with the cruisers Trieste and Gorizia as objectives) and Palermo Harbour. The Maddalena mission fails after the loss of submarine P.311 with Chariots X and XVIII. However, the Palermo operation marks a success. On the night of January 2th, 1943 and January 3rd, 1943, H.M.S. Trooper and H.M.S. Thunderbolt, supported by H.M.S. Unruffled, release five Chariots (XV, XVI, XIX, XXII, XXIII) near the harbour. Mechanical failures force three to be scuttled, but Chariots XXII and XVI succeed. Lieutenant R.T.G. Greenland and Petty Officer A. Ferrier attach explosives to the hull of the cruiser Ulpio Traiano and other vessels, sinking the cruiser and severely damaging the motor vessel Viminale. However, charges on smaller ships fail to detonate. Most operators are captured, and Italian divers recover an intact Chariot.

Operation Welcome is an unsuccessful assault on Tripoli Harbour in January 1943. This mission, intended to disrupt Axis naval operations, fails when the two Chariots involved are lost before reaching their targets. Despite the setback, the Royal Navy continues to develop its underwater assault capabilities. Hydrographic surveys for the Allied invasion of Sicily play a critical role in Operation Husky, providing detailed information about landing beaches on the island’s southern coast. Plans to target major Italian fleet bases, such as those at Taranto and La Spezia, are subsequently drafted but abandoned following the Italian armistice in September 1943.

During Italy’s co-belligerence, Chariots LVIII and LX assist Italian forces in sinking the abandoned cruiser Bolzano at La Spezia on June 22nd, 1944. In April 1945, Mariassalto operators use two Chariots to attack the incomplete aircraft carrier Aquila in Genoa during Operation Toast, aiming to prevent its use as a blockship. Despite partial success, the vessel remains afloat when Genoa is liberated days later.

The Chariot MK II sees limited action, with two craft sinking Japanese-controlled ships in October 1944 near Penang.

| Multimedia |

| Photographs |

| Development |

| Chariot |

![CHARIOT CRAFT AND MEN. 3 MARCH 1944, ROTHESAY.. Image: IWM (A 22121) https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205154348]](https://worldwar2-sof.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/chariot-2.jpg)

| Trials |

| The Men |

| Operations |