| Page Created |

| October 27th, 2024 |

| Last Updated |

| November 1st, 2024 |

| Great Britain |

|

| Related Pages |

| British Aircraft |

| Crew |

| 2 |

| Length |

| 20.7 metres |

| Wide |

| 33.5 metres |

| Height |

| 6.1 metres |

| Weight |

| 8,346 kilograms |

| Loaded Weight |

| 16,329 kilograms |

| Propulsion |

| – |

| Armour |

| – |

| Armament |

| – |

| History |

The glider, demonstrated by the Luftwaffe at the Belgian fort of Eben Emael in 1940, has a significant attraction: like modern troop-lift helicopters, it can land a formed group, usually a platoon, on a compact landing zone. The British require their glider pilots not only to deliver men and equipment safely into battle but also to join the fight as infantry after landing. Paratroops, while less vulnerable, can be scattered by wind or the speed of their exit from the aircraft, delaying their formation into an effective fighting force.

In June 1940 British airborne establishment is formed, following Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s directive, in response to the German airborne tactics seen during the Battle of France. During the development of airborne forces, the War Office decides that gliders will be a crucial part of this new capability, intended to transport troops as well as heavier equipment, which by 1941 includes artillery and tanks.

By early 1941, the War Office issues four specifications for gliders. The first, Air Ministry specification X.10/40, is for an eight-seat glider, inspired by the German DFS 230, which later becomes the General Aircraft Hotspur I. The second specification, X.25/40, results in the Slingsby Hengist, capable of carrying fifteen troops. The third, X.26/40, leads to the 25-seat Airspeed Horsa. Lastly, X.27/40 demands a glider capable of transporting heavy loads, including light tanks.

The British aeronautical industry, already stretched by existing production commitments, has limited capacity for designing and manufacturing gliders. Consequently, the government allocates contracts to suitable firms rather than through competitive bidding. Slingsby is assigned to develop X.25/40 due to its limited size and production capacity, while Airspeed is given the task of building the X.26/40. Having already produced the Hotspur glider, General Aircraft Limited is chosen to develop X.27/40, as it is deemed capable of manufacturing a larger glider.

Prior to their selection, General Aircraft Limited is already working on designs for a glider capable of carrying a Mk VII “Tetrarch” light tank. This glider features a low-wing structure, and the tank driver serves as the pilot, controlling the glider from within the tank using internal modifications. The concept aims to eliminate the need for specialised glider pilots and allow the tank to engage in combat immediately upon landing. Surviving illustrations depict the tank within the glider fuselage with the turret exposed, potentially enabling it to engage targets during landing. However, both General Aircraft Limited and the War Office find the design impractical, leading to a joint decision in January 1941 to pursue a more conventional design.

The revised glider design is primarily made of wood and can carry either a Tetrarch light tank or two Universal Carriers, with a combined maximum load of approximately 7,720 kilograms. A requisition form from the Air Ministry shows the cost of each glider at £50,000. By February 1941, General Aircraft Limited’s chief designer completes the initial design for the glider, designated GAL. 49 and named “Hamilcar”, after the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca.

Since such a large glider has never been constructed by the British military, a half-scale prototype is created for testing. Designated as GAL. 50, the prototype requires an Armstrong Whitworth Whitley medium bomber to tow it into the air and makes its first flight in September 1941. Although the prototype crashes during landing due to an error by the test pilot, the trial is considered successful.

The first full-scale Hamilcar prototype is completed in March 1942 at General Aircraft Limited’s facility in Hanworth, Middlesex. Due to the short length of Hanworth’s airfield, the glider is transported to Royal Air Force Snaith in Yorkshire for its initial flight, which takes place on March 27th, 1942, towed by a Handley Page Halifax bomber. A second prototype is finished in June 1942, with subsequent testing conducted at various airfields, including Royal Air Force Beaulieu’s Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment. All flight trials prove successful, and the production models closely resemble the prototypes.

The number of Hamilcar gliders required by the War Office frequently fluctuates. In May 1942, the War Office requests 360 Hamilcars from General Aircraft Limited for two major airborne operations, but this target proves unrealistic. The production rate for the gliders is too slow, and there are not enough towing aircraft available to support this number. By November 1943, the War Office revises the requirement to 800 gliders, an even more unattainable figure. By the time production ends, only 344 Hamilcars are completed.

General Aircraft Limited initially produces 22 Hamilcars, including two prototypes and ten pre-production models for evaluation. Subsequent production involves subcontractors under the ‘Hamilcar Production Group’, including the Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company, the Co-operative Wholesale Society, and AC Cars. Production is intended to start in late 1941, with 40 to 50 gliders expected by the year’s end. However, this goal is overly ambitious, with the intended number only being reached by June 1944.

The slow production rate is attributed to several factors: shortages of the specific types of wood required for construction, difficulty in finding suitable airfields with skilled personnel to build and store the gliders, and poor management and lack of prioritisation at General Aircraft Limited. Between March and August 1942, General Aircraft Limited promises to deliver eighteen Hamilcars, but by September only one is completed. This prompts the Ministry of Aircraft Production to appoint an Industrial Panel of three senior experts to assess the issues.

The panel visits General Aircraft Limited in early September 1942 and issues a report on September 24th, 1944, identifying the root of the problem as General Aircraft Limited taking on more work than it can handle, compounded by poor organisation and management. Additionally, conflicts between General Aircraft Limited and the Hamilcar Production Group further hinder progress. The Group, formed by the Ministry on July 28th, 1942 to expedite production, faces resistance from General Aircraft Limited management, who fail to fully cooperate. The panel also highlights a “piecemeal method of ordering” by the Ministry as a cause of further delays. Ultimately, several senior managers at General Aircraft Limited are replaced to reduce internal conflicts and improve production efficiency.

The ten pre-production gliders are eventually delivered by the end of 1942, and the first production glider is assembled between March and April 1943. Parts production and glider assembly continue throughout 1943, but schedules continue to lag, especially when the United States Army Air Force express interest in the glider. The United States Army Air Force requires a significant number of Hamilcars for Operation Overlord, the airborne landings in Normandy, and for use in the Far East. This increases pressure on General Aircraft Limited and the Hamilcar Production Group, as the United States Army Air Force requirements necessitate further production and new flight trials to assess performance in tropical conditions.

In late 1943, the United States Army Air Force requests 140 Hamilcars for transporting bulldozers and other construction equipment for airfield building, and it is agreed that 50 will be supplied by June 1944. However, production remains slow, and by February 1944, the United States Army Air Force cancels its request, withdrawing its personnel involved in production, which further delays progress. As a result, only British airborne forces ultimately use the Hamilcar.

By January 1944, only 27 Hamilcars are fully assembled and ready for use, with a total of 53 produced, many of which are still awaiting parts or assembly. The shortage of personnel to assemble the gliders and the availability of airfields for storage continues to be an issue. By June 1944, however, eighty gliders are completed and ready for use, in time for limited deployment during Operation Tonga, the British airborne landings in Normandy.

| Operational Use |

The General Aircraft Limited Hamilcar gliders are flown by C Squadron of the Glider Pilot Regiment. C Squadron serves as the heavy glider unit within No. 2 Wing. The squadron consists of No. 6 Flight and No. 7 Flight and is stationed at Tarrant Rushton in Dorset for much of the war. Major Jim A.C. Dale commands C Squadron, with Captain Bernard Halsall leading No. 6 Flight and Captain Freddie C Aston in charge of No. 7 Flight.

Base Recovery Units are founded by the Royal Air Force trained to recover the gliders once landed. This allowed the gliders to be used again after operational use.

The Hamilcar gliders are deployed on three occasions, exclusively in support of British airborne forces. Their first use occurs in June 1944 during Operation Tonga, when around thirty Hamilcars transport Ordnance QF 17-pounder anti-tank guns, transport vehicles, and Tetrarch light tanks into Normandy to support British airborne troops. In September 1944, a similar number of Hamilcars are used to deliver anti-tank guns, transport vehicles, and supplies for airborne forces during Operation Market Garden. The third and final deployment of the Hamilcars takes place in March 1945 during Operation Varsity, transporting M22 Locust light tanks and other supplies. The gliders prove effective in all three operations, although their slow speed and large size make them vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire, resulting in several being damaged or destroyed.

Production of the Hamilcar continues until the end of the conflict, finally concluding in 1946, with a total of 344 gliders built.

The Hamilcar remains in service for several years following the end of the Second World War. The Hamilcar proves particularly valuable for transporting large and heavy loads. On December 31st, 1945, records indicate that 64 Hamilcars are stationed at Royal Air Force Tarrant Rushton, where they are utilised for routine training exercises. In January 1946, the process of disposing of surplus Hamilcars begins, with 44 moved to disposal facilities, leaving twenty still in service. These remaining gliders continue to be used for routine flying exercises until July 1946, when six are withdrawn from service due to glue deterioration. By February 1947, only twelve Hamilcars are still operational. These final units remain in use until 1950, with several participating in airshows and public displays organised by the Royal Air Force, before eventually being phased out as obsolete by the mid-1950’s.

| Design and Features of the Hamilcar Glider |

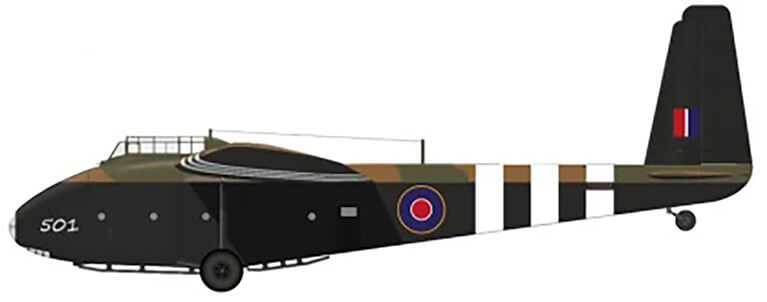

The Hamilcar glider is constructed primarily from wood, mainly birch and spruce, with a fabric-covered plywood skin and high-grade steel reinforcement beams in critical areas. It has a wingspan of 33.5 metres, a length of 20.7 metres, and a height of 6.1 metres to the top of the fin with the tail down. The empty weight is 8,346 kilograms, and it can carry a military load of 7,983 kilograms, resulting in a total weight of 16,329 kilograms. The entire aircraft is designed to be disassembled into smaller sections for transport.

Due to its size and weight, the Hamilcar requires the largest and most powerful aircraft to tow it; typically, four-engine bombers like the Handley Page Halifax are used. Both the wing and cockpit are positioned above the fuselage to maximise space in the cargo compartment and facilitate the loading of vehicles. The cargo area measures approximately 9.6 metres in length, 2.4 metres in width, and between 1.8 and 2.3 metres in height. The nose of the glider is hinged and opens to the side to ease loading, while the two pilots are seated in tandem in a cockpit atop the fuselage, accessed via an internal ladder around 4.6 metres above the ground. Eventually, the pilots are protected by a bulletproof windscreen and an armour plate behind the second pilot. An intercom system is added to allow communication between the pilots and personnel below.

An initial feature, later removed before full-scale production, is an under-fuselage hatch intended to allow the prone firing of a Bren light machine gun during approach to the landing zone. The Hamilcar’s length-to-wingspan ratio is similar to that of the Avro Lancaster bomber, which has a wingspan of 31 metres and a length of 21.2 metres. Unlike modern sport gliders with extended wingspans to improve gliding performance, the Hamilcar is designed for military use, intended to be released at a low altitude close to the landing zone to conduct a steep descent, minimising time in the air and exposure to enemy fire.

The glider is fitted with large flaps that assist in a steep and rapid descent. Adjusting the flap angles during landing allows for precise control over the descent rate and landing point, while also enabling a lower touchdown speed. The flaps are operated using a small bottle of compressed air, sufficient for a single landing, which saves weight and reduces the risk of an explosion if hit by enemy fire. The standard approach speed for the Hamilcar is 128 km/h, which can be reduced for shorter landings, and its stalling speeds vary depending on flap configuration.

The Hamilcar has a tailwheel landing gear with oleo-pneumatic shock absorbers, which can be deflated to lower the fuselage nose for loading or unloading purposes. Initially, the glider is designed with a jettisonable undercarriage, as it is found to travel a shorter distance when landing on skids. However, this is later replaced with a fixed undercarriage, as pilots prefer landing on wheels for greater control and the ability to avoid other gliders during landings. The wheeled undercarriage is not fitted until after the glider is loaded, using two 15-ton jacks to lift the aircraft for fitting.

When carrying tanks or other vehicles, it is standard practice to start their engines in the air, usually just before the glider is released from the tug. Special exhaust ducts are fitted to expel fumes. The Tetrarch and M22 Locust light tanks are so large they barely fit inside the glider, and their crews remain inside the tanks for the entire flight. Upon landing, the driver releases the anchorages by pulling a lanyard, and then drives the tank forward, which automatically operates the swing door release. Other vehicles, such as Universal Carriers, rely on the pilot to manually operate the door release. The pilot exits the cockpit, slides down the fuselage, drops to the ground, releases hydraulic fluid from the undercarriage legs, and then enters the glider to operate the door release line. If the swing door jams, it is possible for tanks to break through the forward fuselage to exit, which occurs in both airborne operations where Hamilcars transport tanks.

| Versions |

Several variants of the Hamilcar Mark I are planned, but only one is actually produced. The Hamilcar Mark X, also known as the GAL.58, is developed under specification X 4/44 to adapt the glider for use in the tropical climate of the Pacific. High temperatures and the altitude of many airfields reduce the efficiency of piston engines, making it challenging for Halifax bombers to tow Hamilcars without significantly reducing their fuel load, which in turn limits the range of the glider.

Two initial solutions are proposed to address this issue. The first involves converting a Hamilcar for rocket-assisted take-off (RATO). Two steel cylinders, each containing twenty-four 76 mm rockets, are attached to the sides of the glider to provide 89 kN of thrust during take-off; the cylinders are then jettisoned once airborne. Initial trials in January 1943 prove successful, but the idea is not pursued further for unknown reasons. The second solution involves double towing, where two Halifax bombers are used—one stripped of all unnecessary equipment—each attaching a tow rope to the Hamilcar. Once airborne, the normal Halifax would detach and land, while the modified Halifax continues towing the glider. However, this method does not advance beyond initial trials in England due to the high risk of serious accidents.

Instead, a powered version of the Hamilcar, the Mark X, is chosen, offering potential for long-range operations and the ability to retrieve the glider after use. Development begins in November 1943 when Allied planning considers the possibility of airborne operations against Japan. However, progress is relaxed, and the first production model is not available until early 1945.

The first prototype is converted from a Hamilcar Mark I, with two Bristol Mercury radial piston engines, each producing 965 horsepower, added to the wings. The wings and fuselage are reinforced to support the engines. Additional controls are installed in the cockpit, duplicated for both pilot positions, although limited space means the glider can only be started from the rear seat. Fuel tanks are added to the wings, with an option for a third tank in the fuselage. These modifications increase the glider’s weight to 21,319 kg, but its dimensions and cargo capacity remain unchanged.

The Hamilcar Mark X makes its first flight under its own power in February 1945, and initial trials demonstrate that it performs as expected. With the engines installed, the Mark X can be towed by a fully loaded Halifax, achieving an operational radius of approximately 1,448 km. However, when fully loaded and taking off under its own power, the glider cannot maintain altitude even at full engine power, necessitating a reduction in its cargo load to decrease weight to 14,742 kg.

Two Hamilcar Mark I gliders are converted for initial trials, and following satisfactory results, a further eight Mark I gliders are converted, with ten Mark Xs built from scratch. Additional orders are cancelled when the war ends in August 1945, although further tests are conducted in the United States.

Another variant of the Hamilcar is proposed but never moves beyond the design stage. This concept involves mounting a Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter above the Hamilcar, allowing the fighter to provide enough power to keep both aircraft in flight and relieve the glider pilots from flying duties until it is time to detach for landing.

The Hamilcar X is less sensitive to balance and centre of gravity issues compared to the unpowered glider, which needs ballast when lightly loaded. The Hamilcar X’s performance under its own power and at maximum weight is similar to that when towed. At a weight of 14,742 kg, it can take off within 1,267 metres. It has a maximum speed of 233 km/h and cruises at 193 km/h. With 1,818 litres of fuel, it can cover 1,135 km in still air, or 2,697 km with 3,909 litres of fuel replacing the cargo load.

| Multimedia |

| Hamilcar |

| Hamilcar loading a Tetrarch |

| Hamilcar Recovery |

| Hamilcar GAL. 58 Mark X |