| Page Created |

| January 30th, 2023 |

| Last Updated |

| March 19th, 2023 |

| Country |

|

| Additional Information |

| Unit Order of Battle Commanders Operations Equipment Multimedia Sources Interactive Page |

| Badge |

|

| Motto |

| Any Place, Any Time, Any Where |

| Founded |

| September 13th, 1943 |

| Disbanded |

| October 8th, 1948 |

| Theater of Operations |

| India Burma |

| Organisational History |

In July, the British Prime Minister Churchill summons, General Wingate, commander of the Chindits to London to talk about the Chindit Long-Range Penetration (LRP) operation, Operation Longcloth, in Burma. After speaking with him, the Prime Minister invites Wingate to the Quadrant Conference in Quebec, Canada. The goal of the conference was to determine Allied strategy, with a focus on the European Theater but also covering Burma operations. Churchill wants Wingate to present his recent Long-Range Penetration operation and views on its future use. At the conference, Wingate proposed increasing Long-Range Penetration units to eight brigades for the 1943-1944 dry season offensive. Four would lead the attack and four would be in reserve, with a 90-day combat limit before rotation. The main objectives included occupying Bhamo and Lashio, securing Katha-lndaw airfield and advancing towards Pinlebu and Kalewa, and attacking Ledo towards Myitkina. Wingate’s Long-Range Penetration units would coordinate with British and Chinese forces with the limited goal of conquering Burma north of the 23rd Parallel. Wingate’s plan also includes aircraft support, such as sixteen DC-3 aircraft for parachute operations and a bomber squadron per unit for close air support. At the suggestion of Royal Air Force liaison officer Squadron Leader Robert Thompson, Wingate requests a “Light Plane Force” to evacuate wounded Long-Range Penetration personnel. The United States approves of reopening the Burma Road and British had to seek their assistance.

Due to high demands for war materials in Europe, the British supply capability is stretched thin, causing the China Burma India (CBI) Theater to have the lowest priority. Essential items like food, weapons, vehicles, planes, and medicine are in short supply. The British cannot fulfill General Wingate’s Quadrant plan demands for two Long Range Patrol brigades, DC-3 Dakotas, and evacuation aircraft. Churchill believes England has enough bombers but lacks the other resources. At the Quadrant Conference, Churchill has Wingate brief President Roosevelt, who approves the mission, leading to Churchill’s request for American support. The US President endorses the plan and passes Churchill’s request through channels to US General Arnold, who saw a chance to expand airpower. Arnold aims to form a new air organisation dedicated to supporting Wingate’s troops on the ground in Burma, with the success dependent on his choice of commander.

On August 26th, 1943, Lord Mountbatten, the newly appointed Supreme Allied Commander of SEAC, meets with General Arnold to talk about CBI (China-Burma-India) Theater plans. Mountbatten suggests expanding on General Wingate’s mission, to which Arnold reaffirms his support for Long-Range Penetration and pledges to create an independent organisation for the purpose. Arnold envisioned this new force as a highly mobile fighting unit with its own transportation and services.

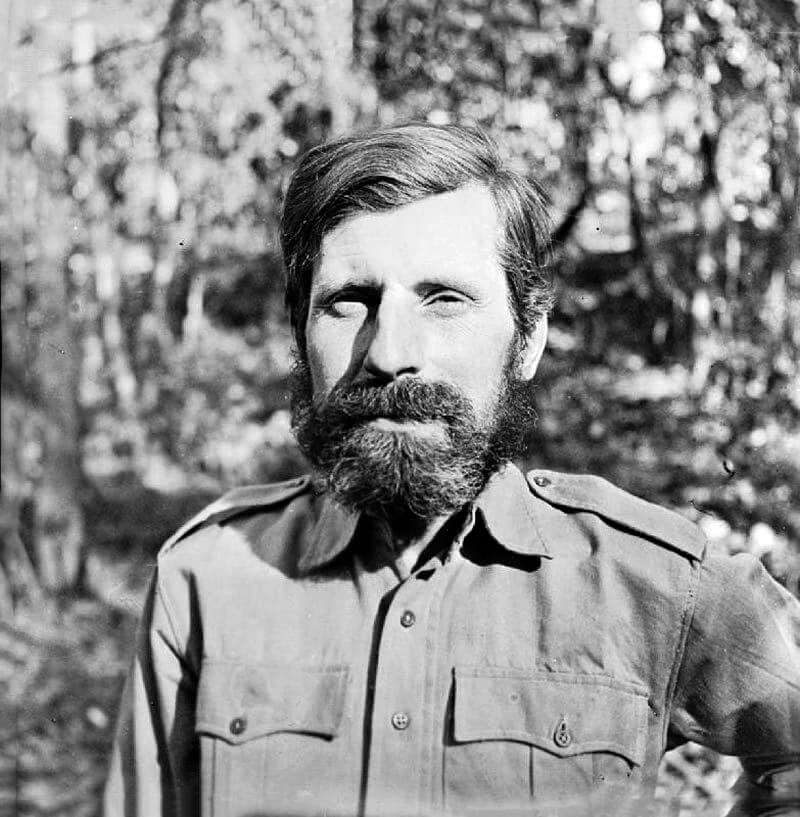

General Arnold searched for men who could bring the US “can-do” spirit to the CBI (China-Burma-India) Theater. He was concerned about past experiences where unique forces were absorbed and lost their purpose in the theater. Therefore, he saw the selection of the commander as crucial, as they would impact the unit’s composition, morale, and employment. After staff members submit five nominations, the search is narrowed down to two individuals: Lieutenant Colonel Philip G. Cochran and Lieutenant Colonel John R. Alison.

Philip G. Cochran is considered a desirable candidate due to his confidence, aggressiveness, imagination, and successful war record as a fighter pilot. He trained a group of thirty-five replacement pilots in Morocco as the Joker Squadron before being sent to Tunisia to reinforce two P-40 squadrons. Cochran becomes the leader of the 58th Squadron and leads successful raids on Axis truck and train routes, causing the Germans to move supplies at night. He personally destroys the German headquarters at Kairouan and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, Croix de Guerre, and others for his combat achievements. Cochran is also the inspiration for the character of Flip Corkin in the comic strip “Terry and the Pirates”. General Arnold did not know Cochran but recognises John R. Alison as a candidate for qualities desired by him. Alison is a tactful, organised pilot with a great flying record and experience in the Far East. As a 1936 engineering graduate from the University of Florida, he uses his technical skills for the US-Russian lend-lease program of P-40 aircraft in Russia in 1941. Alison and Captain Hubert Zemke teach Russian pilots to operate the planes, but when Zemke leaves for the numbing Russian winter, Alison stays on as the Assistant Military Attache for Air. In April 1942, he is officially declared absent without leave (AWOL) but had attached himself to a small engineering unit assisting the British with lend-lease A-20’s. In June, he is sent to the China Theater as a pilot for US Major General Claire L. Chennault’s 23rd Fighter Group and becomes an ace by downing six enemy aircraft. Alison returns to the United States in May 1943 and is training the 367th Fighter Group when General Arnold summoned him for an interview.

|  |

| Lieutenant Colonel Philip G. Cochran | Lieutenant Colonel John R. Alison |

During the interviews with the two men General Arnold looks for a leader for his unique organisation who has aggressive, imaginative, and highly organised qualities. He found that both Cochran and Alison possessed these qualities but has difficulty choosing one over the other. Eventually, he names them co-commanders and finally outlines the details of the project.

To gain a better understanding of Long Range Penetration (LRP) and the purpose of the new unit, Lieutenant Colonel Cochran travels to England to meet with Admiral Mountbatten and General Wingate. During their discussions about the past campaign and the theory of long-range penetration, Cochran starts to put together General Arnold’s vision for the project, referred to as Project 9. After his conversations with Wingate, Cochran expands his ideas for the mission of Project 9. Influenced by the 1943 Chindit campaign and emphasising the principle of air support in Long Range Penetration (LRP), Cochran and Alison take on the task of fulfilling all of Wingate’s air needs. They aim to create a miniature area of warfare that would include ground troops, artillery, infantry, air and ground support, fighter support, and bombardment support.

Cochran and Alison have to use their imagination to create a table of organisation for Projects 9 as there is no established unit of this kind. They are given a lot of freedom by General Arnold to gather men and resources under high priority. The first personnel assignments included Major Samson Smith as Executive Officer, Major Arvid E. Olson as Operations Officer, and Captain Charles L. Engelhardt as Administrative Assistant. Later, Captain Robert E. Moist is added as Adjutant. The recruitment process is made easier by the appeal of combat duty and the secretive nature of the project. Applicants are only told a minimal amount of information and are not told the destination. Cochran and Alison select Major Grant Mahony to lead the fighter section, with support from other experienced pilots and crew members. The fighter section is proposed to provide air support to LRP (Long Range Penetration) units and test Wingate’s theory of airborne artillery. After being denied the requested P-38 Lightnings, Cochran and Alison substitute them with P-47 Thunderbolts and requests thirty aircraft.

For transport requirements, three separate units are proposed for transport-, glider-, and light-cargo airplanes. Major William T. Cherry, Jr. is selected to lead the transport section, with Captain Jacob B. Sartz as his deputy. The glider section is proposed to transport heavy artillery and resupply the Chindits, with Captain William H. Taylor, Jr. and 1st Lieutenant Vincent Rose selected as commander and deputy. The light-cargo section is led by Lieutenant Colonel Clinton B. Gaty and is needed for unit support and maintenance. Captain Edward Wagner is selected to assist Lieutenant Colonel Gaty.

The transport section requests thirteen C-47 Dakotas, the glider section one hundred CG-4A Waco gliders and twenty-five TG-5 training gliders, and the light-cargo section selects the UC-64 Noorduyn Norseman for unit support. The L-1 Vigilant is requested for the Light Plane Force. It has the capability to carry 2-3 stretchers and has a short take-off distance. Major Rebori needs one hundred of these planes, but due to a shortage of serviceable aircraft, he adds the newer L-5 Sentinel to the fleet. Although the L-5 is faster, it can only carry one patient and required a much longer runway of nine hundred metres making it less desirable.

Cochran and Alison also decide to use the new helicopter for rescue missions in Burma. Alison is tasked with securing the YR-4 helicopter for the jungle rescue service. Despite initial setbacks, Alison successfully convinces Wright Field to send a representative to India to test the Sikorsky helicopters in real combat.

The equipment of the organisation is equivalent to a United States Air Force wing with 2,000 personnel. However, due to time constraints, all Project 9 personnel had to be air transported, requiring a leaner setup with eighty-seven officers and 436 enlisted men to cover medical, supply, engineering, intelligence, and communication sections.

Lieutenant Colonel Cochran and Alison submit their proposed organisation to General Arnold, who receives approval from General George Marshall on September 13th, 1943. The only change was the use of P-51 A Mustangs instead of Thunderbolts for the fighters. In less than a month, Cochran and Alison had formed the unit and received approval. Their next step is to activate the unit and train the personnel for deployment.

The formation of the unit leads to the men feeling exceptional and acting accordingly. Project 9 begins acquiring specialised equipment in North Carolina on October 1st, 1943, with fighters and gliders at Seymour-Johnson Field and light planes at Raleigh-Durham. Innovative ideas are promoted, leading to the inclusion of a mobile hospital and plans for experimental rocket tubes for the fighters. The Dakotas are equipped with the latest glider towing reel and the Waco’s with gyro towing devices. Major Rebori designs bomb racks for parachute packs on the wings of the L-1 and L-5 aircraft. The co-commanders convince the army to issue weapons to all flyers, and they train in spare time at the rifle range instead of the typical Port of Embarkation training. Flight training is also conducted in North Carolina, with the fighter sections receiving training on the P-51A and its Allison engine and the gliders practicing flying techniques. Double tow is emphasised for airlift capability and two C-47 pilots are asked to join Project 9 after showing their skills.

The light plane pilots are also working with gliders by towing TG-5 training gliders, but their primary focus is getting familiar with their aircraft. Both the outdated L-1 and the new-to-the-USAAF L-5 aircraft pose a challenge for the “flying sergeants,” as they have not flown either plane, especially not under the difficult conditions they will face in Burma. To prepare the pilots, Major Rebori creates a simulation by stretching ropes across the runway at Raleigh-Durham and having the pilots practice short-field landings and take-offs repeatedly. With their aircraft fully loaded, the pilots can take off in as little as 500-600 metres and are honing their low-level flying skills. When residents complain about the planes flying low, Major Rebori replies that they should be flying even lower.

Due to the earlier departure date, the group must shorten their entire training program. As the departure date nears, the unit’s morale is high. The first group to leave Goldsboro receives gear, including ammunition, and some of them are discharging their weapons in the railway station while waiting for the train. However, bullets are not given to subsequent groups. With a transportation priority that allows them to bypass even generals, the unit is poised to fly from Miami to Karachi, India, via stops in Puerto Rico, Trinidad, British Guiana, Brazil, Ascension Island, Gold Coast, Nigeria, Ango-Egyptian Sudan, Aden, and Mastra Island. Colonel Cochran sets off earlier, leaving Miami on November 3rd, 1943, ahead of the main unit.

General Arnold keeps his promise and puts the organisation under the authority of South East Asia Command (SEAC) by sending a letter to Major General George Stratemeyer, who is part of Mountbatten’s staff and soon to be the commander of the Eastern Air Command. The letter, dated September 13th, 1943, states that “the Air Task Force will be assigned to the Commanding General of the United States Army Forces in the China-India-Burma Theater for administration and supply and will operate under the control of the Allied Commander-in-Chief, South-East Asia.” General Arnold also clearly defines the objectives of Project 9 as:

- Supporting the forward movement of the Chindit columns.

- Supporting the supply and evacuation of the columns.

- Providing a small air cover and strike force.

- Gaining air experience under expected conditions.

Colonel Cochran arrives in India with the mission defined by General Arnold. He first must meet up with Admiral Mountbatten. Secondly, he needs to find facilities for his personnel and aircraft, and thirdly he must complete the training programs. Despite an engine change and a brief delay, Cochran and a small group of his men arrive in Western India on November 13th, 1943. Cochran’s first priority was to report to Delhi, where Admiral Mountbatten has temporarily established his headquarters. When Cochran first met with the South East Asia Command (SEAC) staff, the details of General Arnold’s letter are not well-known, and changes are made to the Quadrant Conference plans.

When Colonel Cochran arrives, the initial plan for Wingate’s operation was to have three long-range penetration brigades march into Burma. One would cross the Chindwin River from the West, another would march down from the North, and a third would be flown to China and march across the Salween to spearhead a Chinese advance. However, due to airlift limitations, General Stilwell declares that this would be impossible and that the entire plan for offensive operations in Burma was in danger of being scrapped.

At a meeting attended by General Auchinleck, the Commander-in-Chief in India, General Stilwell, the Deputy Supreme Commander of SEAC, General Chennault, the Commander of the 14th Air Force, Admiral Mountbatten, and General Stratemeyer’s representative, Colonel Cochran is asked to explain the purpose of the 1st Air Commando Group’s presence in the theater. Despite being unaware of the group’s intended involvement in Wingate’s operation, he explains that it is not necessary to fly the third brigade to China, and that the 1st Air Commando Force could move the brigade directly into the heart of Burma from bases in India. When asked if this is feasible, and if the 1st Air Commando Force could complete the task in two weeks’ time. Colonel Cochran confidently replies that they could do it in one week or less.

On November 24th, 1943, Colonel Cochran reinforces his statement by sending a cable to Colonel Alison in the United States, asking for an additional 50 GC-4A Waco gliders. Despite being a politically charged issue, the mission is back on track for the time being. The next day, the extra gliders leave the US for India.

As the unit’s aircraft start to arrive, Cochran makes plans for their facilities. To hasten the equipment’s arrival, the C-47 Dakotas are flown over the same route as the rest of the personnel. All other planes are shipped by sea: the P-51A Mustangs are loaded onto carriers and everything else is disassembled and crated, except for the gliders. The non-glider aircraft head for Karachi.

He secures Karachi Airport dirigible hangar to assemble the unit’s aircraft. However, just before Christmas, two shipments of P-51A Mustangs are received in inoperable condition due to saltwater corrosion and storm damage. No replacements are available in the theater, so priority spares are ordered. The crated planes are in better shape. The unit’s officers and enlisted men help to put together the UC-64 and L-series planes as the crates are unloaded. Visitors to the site are impressed by the unit’s spirit of cooperation.

Project 9 establishes a temporary headquarters near Karachi at the Malir Airfield and is renamed as the 5318th provisional unit (Air). At Karachi it starts training its exercises and theater orientation. On December 1st, 1943, the glider section is transported to Barrackpore Airfield near Calcutta to rig and test the gliders. Although all gliders are supposed to be shipped to Calcutta, on December 23rd, 1943, Captain Taylor is forced to send four of his personnel to Karachi to assemble some gliders that were mistakenly sent there. As the gliders are rigged, the pilots practice and evaluate each one by test flying them.

Colonel Alison arrives on Christmas Eve and joins military officials including Colonel Cochran, Captain Taylor, and others as they fly to Northeast India’s Assam region to survey two airfields, Lalaghat and Hailakandi. The airfields have grass strips built in a British style with barracks made of native bamboo huts. The group decides that Lalaghat’s 1,900 metres strip will be used for transports and gliders while Hailakandi, located on a tea plantation and only 1,400 metres long, will be for the fighters and light planes.

Initially, Lieutenant Colonel Gaty is to command Lalaghat and Cochran to run Hailakandi. After the arrival of Colonel Alison both co-commanders decide that the co-command arrangement is awkward. To simplify things, they decide that Colonel Cochran becomes the commander and Colonel Alison takes on the role of his deputy. They are in such accord that a decision by one is automatically accepted by the other.

With a permanent home secured, Cochran and Alison focus their attention on supporting Wingate’s 3rd Indian Division, also known as Special Force. The 5318th conducts training exercises with the Chindits, enlarges their assault force, and gains air experience under the conditions they will encounter in future missions, in accordance with General Arnold’s fourth purpose.

While rigging gliders, Captain Taylor’s men conduct joint training drills with the Chindits, strengthening the bond between the two units. Flight training begins on December 29th, 1943, with a 20-glider exercise ten days later that successfully lands four hundred men on a mud field at Lalitpur, despite four gliders did not releasing. The gliders, however, get stuck in the mud and can’t be moved by ground personnel. To solve the problem, Colonel Cochran arranges to have the gliders “snatched” out during the night and the following morning.

During a day training exercise, the assault force reassures concerns about the evacuation airplanes. 1st Lieutenant Paul G. Forcey, a former RAF pilot, demonstrates the survivability of a L-5 Sentinel to the Chindits by performing a mock dogfight with Major Petit in a Mustang. Using the smaller radius to his advantage, Forcey continually outmaneuvers the faster aircraft, as verified by gun cameras.

These exercises help the Special Forces and Colonel Cochran’s men find solutions to each difficulty they face. For example, they find a solution to the problem of transporting mules. After considering various suggestions, they finally test the feasibility of transporting the animals in gliders on January 10th, 1944. The glider floors are reinforced, the mules’ legs are hobbled, their heads are tied down to keep the ears out of the control cables, and they are restricted in a sling-like contraption. Flight Officer Allen Hall, Jr. is selected to fly the glider, with last-minute instructions given to the muleteers to shoot the animals if they become unmanageable. The worries are unfounded, as the mules perform well and reportedly even bank during turns.

After the nighttime session, General Wingate is inspired to participate in a “snatch” exercise. Admiral Mountbatten, who also attends the exercise, is impressed, and discusses expanding the mission with General Wingate and Colonel Cochran. They agree to send a team of Chindits and an engineering unit in gliders to clear jungle areas in Burma. The Chindits will defend the engineers as they clear a landing strip for C-47 Dakotas. Once the strip is built, the rest of General Wingate’s brigades can be airlifted behind enemy lines. Captain Taylor supports the idea and continues daily glider training as the unit prepares Lalaghat and Hailakandi for operation. The 5318th Provisional Unit follows the established procedures as used at Karachi to make the airfields operational.

Officers and enlisted personnel work together to transfer oil and fuel drums from Dimapur to Lalaghat and Hailakandi. The men of the 5318th work around the clock, straining petroleum through chamois skins to remove rust and impurities, disregarding their own physical exhaustion.

Meanwhile, as glider training continues, Captain Taylor decides against the normal 360-degree overhead landing pattern and opts for a quicker straight-in approach. The release point for the gliders is established two hundred meters ahead of the landing field, marked with four lights in a diamond shape, 150 metres on each side, creating two landing strips. However, on February 15th, 1944, a night double tow leads to a mishap killing four British and three US troops. The next day, General Wingate’s unit commander lifts the potential negative impact with a message: “Please be assured that we will go with your boys any place, any time, anywhere.” This phrase captures the high degree of teamwork between the British and American groups and becomes the motto of the 1st Air Commandos. On the other hand, Royal Air Force support for the Chindits is not as well coordinated. This, along with the need for an engineering unit, leads to the growth of the 5318th Provisional Unit one last time. This enlargement happens when issues arise regarding the Royal Air Force’s bomber support to General Wingate’s columns. The Royal Air Force recently equipped their bombers with radios that are incompatible with the Chindits’. Facing the same slow response from the Royal Air Force as during the first Chindit operation, General Wingate appeals to Colonel Cochran. As a result, Colonel Cochran requests twelve North American B-25H Mitchell medium bombers to be diverted from the theater to the 5318th Provisional Unit (Air). Washington agrees and Colonel Alison secures the commitment by January 21st, 1944. Although Colonel Cochran gets the planes in early February, he is unable to secure experienced crews, so he decides to use fighter pilots instead. He assigns some inexperienced B-25 crew to other aircraft within the 5318th and reasons that the B-25H model is ideal for close air support due to its equipment of six 50-caliber machine guns and a 75 mm cannon. The B-25H requires only one pilot and can be flown much like a fighter, convincing Colonel Cochran to have Major R. T. (Tadpole) Smith as the B-25H section commander and Major Walter V. Radovich as his deputy.

The last addition of the 5318th Provisional Unit is the addition of the 900th Airborne Engineers Company. Their mission is to construct airfields in Japanese-occupied territories. Equipped with air-transportable tractors, road graders, and bulldozers, the company immediately begins training by building a new landing strip east of Lalaghat. 1st Lieutenant Patrick H. Casey leads the 900th Engineers.

In February, the light aircraft are split into four groups and deployed to various locations in India. A Squadron is dispatched to Ledo to assist General Wingate’s 16th Brigade, B Squadron is sent to Taro to support General Stilwell, C Squadron is sent to Tamu in preparation for the invasion of Burma, and ten planes from D Squadron are temporarily sent to the Arakan front for additional support.

During the month of February, the unit starts performing their first missions. The intelligence collected some of these missions is just as important as the missions themselves. High-ranking Chindits join the B-25 Mitchell missions to identify potential jungle clearings for the invasion, assisted by the 10th Combat Camera Unit using handheld cameras. The commander, 1st Lieutenant Charles L. Russhon, develops the pictures at night in the open with a sentry standing guard and a nearby well providing water. Pilots also report on enemy defenses, troop movements, and supply lines. This information, along with aerial images, is used by General Wingate’s staff to plan Operation Thursday.

During their time in India and Burma, the unit had evolved from a small air operation to a substantial assault force. With its growth, the definition of mission support shifted, exemplified by the use of gliders. Initially intended for resupply, Colonel Cochran proposed their utilisation to airlift one of General Wingate’s brigades. Later, the idea of constructing a fortified airstrip was presented, leading to a change in the role of the gliders. After completing training on March 5th, 1944, No. 1 Air Commando Force was ready to carry out its portion of the Quadrant Conference plan. However, even as the operation’s launch approached, events raised concerns about its successful execution. The upcoming Allied invasion of Burma would be a test of General Arnold’s vision.

Since the Wingate’s Chindits are not in action in January 1944, General Stilwell attempts to incorporate No. 1 Air Commando Force into his operations, but this is declined after a letter from General Arnold. Despite this, other CBI units attempted to access the unit’s resources. General Arnold’s letter to Admiral Mountbatten makes it clear that No. 1 Air Commando Force is to support General Wingate only. However, the efforts of Admiral Mountbatten’s staff result in the loss of support from Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Army and General Slim’s 14th Corps is not committed to the invasion. This leaves only General Stilwell and General Wingate’s 16th Brigade advancing into Burma.

General Wingate releases two American Long Range Patrols units, known as Merrill’s Marauders, to assist General Stilwell in January. By February 4th, 1944, while General Stilwell is marching down the Hukawng Valley, General Wingate receives new orders for his mission. The orders are to assist the advance of General Stilwell’s troops, create a favourable situation for Chinese forces, and inflict maximum damage on enemy forces in North Burma.

On February 5th, 1944, the first Chindit units of Operation Thursday start moving, and the No. 1 Air Commando Force is tasked with providing fighter cover, bombing support, and air transportation for the Chindits (also known as Wingate’s Raiders) who were conducting guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines in Burma. Their operations encompassed the delivery of troops, food, and equipment through airdrops and landings, the evacuation of casualties, and attacks on enemy airfields and communication lines.

On March 13th, 1945, just two days after Operation Thursday wrapped up, Japanese fighter planes finally locate Broadway and attempt to displace the air commandos stationed there. In preparation for this eventuality, General Wingate had strategically positioned Royal Air Force Spitfires and P-51 A Mustangs on the field. Unfortunately, these fighter planes prove too susceptible to enemy attacks. The Japanese launch air assaults daily, causing minimal personnel casualties but damaging radio equipment, early warning radar sets, and a few light planes. Despite this, the Allies maintain in control of the jungle fortress. Later on, Japanese ground troops attack, Colonel Claude Rome and his Chindit garrison at Broadway but the Japanese are ultimately repelled. In an act of frustration, the Japanese attack the light planes with bayonets before retreating into the jungle. Nevertheless, the airfield is never overrun, and it eventually grows to include maintenance shops, a hospital, a small garden, and even a chicken farm.

On March 25th, 1944, the unit is redesignated as the 1st Air Commando Group. More changes mark the end of March, as the leadership of the L-l/L-5 section switched hands. This alteration became necessary when one of the squadrons was relocated to a Burmese airfield called Dixie, and intelligence reports warned of imminent enemy advancement in the region. Unfortunately, the evacuation from Dixie was not carried out effectively, with code books and reports left behind, and Staff Sergeant Raymond J. Ruksas uninformed of the field’s abandonment, landing there. Although the enemy did not manage to penetrate the camp during Ruksas’s absence, the debacle leads Cololnel Cochran to modify the organisation of the light plane section. In particular, the four squadrons’ operations prove difficult to monitor effectively, and thus the L-series aircraft are placed under Lieutenant Colonel Gaty’s command.

The second key change is that Colonel Cochran lost his right-hand man, as Colonel Alison is called home by General Arnold on March 28th, 1945. Alison is needed to help establish additional air commando units, and he wastes no time returning to India, commandeering a damaged Royal Air Force Dakota plane for the trip. Being unfamiliar with the C-47, he requests assistance from a pilot at Hailakandi before landing. However, shortly after touching down, Colonel Alison is summoned to provide a briefing on Operation Thursday to General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s European Theater Staff. He leaves India for Washington via the British Isles on April 1st, 1944.

Starting from April 1944, the 1st Air Commando Group begins receiving P-51B Mustangs with enhanced performance, which are eventually replaced by D-Model P-47 Thunderbolt fighters by September 1945. They also phase out their B-25 Mitchell bomber section in May 1944. In September 1944, the original unit is merged with the new establishment’s headquarters component to form the 1st Air Commando Group. The former sections are replaced by a troop carrier squadron, two fighter squadrons, and three liaison squadrons, which continue to provide supply, evacuation, and liaison services for the allied forces in Burma. The group also attacks various targets in Burma, such as bridges, railroads, airfields, barges, oil wells, and troop positions while escorting bombers to Rangoon and other targets in Burma. This halts with the monsoons arriving.

Despite the increasing danger, Colonel Cochran makes a risky decision to continue operating out of the airfields in Eastern India for as long as possible. However, the heavy monsoon rains transform the grass strips at Hailakandi and Lalaghat into mud pits, and Colonel Cochran knows he has waited too long when a particularly fierce rainstorm floods the landing strip with several feet of water. Consequently, he orders the air commandos to evacuate back to Asansol, an abandoned British airfield in Central India before it was too late. On May 23rd, 1944, the last UC-64 barely managed to take off from the Halakandi strip amid the pouring rain.

Once the air commandos reached Asansol, the number of personnel began to decrease. Colonel Cochran convinces General Stilwell to send home those who have completed two tours of duty in the war, including himself. He leaves his command of the 1st Air Commando Group to Colonel Gaty who entrusts Lieutenant Colonel Boebel with leading the far-flung light plane section.

Upon taking over, Lieutenant Colonel Boebel orders all the light planes back to India, unaware that a part of his section had remain in Burma to transport casualties to hospitals. Without the support of the light planes, the 111th Brigade retreats from Blackpool on May 24th, 1944, and flees west towards Lake Indawgyi. During the withdrawal, American pilots from the Light Plane Force continue to shuttle the sick and wounded to safety. According to Colonel Masters, the support he receives from the American pilots is invaluable, as they came hour after hour and day after day to evacuate the casualties. A group of eight light plane pilots continues to evacuate the sick and wounded until a new solution is found. Finally, Colonel Masters convinces General Lentaigne to divert a Sunderland seaplane from the Bay of Bengal to Lake Indawgyi to assist the effort. In total, almost four hundred casualties are airlifted to hospitals northeast of Dimapur. When Lieutenant Colonel Boebel discovers that some of his pilots were still in Burma, he immediately orders them to return to India. This marks the end of the 1st Air Commando Group’s actions during Operation Thursday.

General Arnold recognises the impact of his vision on the Japanese even before the monsoon season of 1944 and their defeat at Imphal and Kohima. He begins planning the creation of more air commando units shortly after Operation Thursday. With the 1st Air Commando Group, he had a way of projecting air power without relying on ground transportation, which could be especially useful in a region like Burma where surface communication lines were often impossible. General Arnold intends to deploy four more air commando groups and associated cargo support to India to airlift the British Army further into Central and Southern Burma, with the goal of retaking the country from the air.

General Arnold sees the 1st Air Commando Group and the Troop Carrier Command as two complementary organisations, with the former seizing and defending landing sites and providing close air support to ground troops, and the latter providing large-scale air transport of ground troops and supplies to forward areas established by the Air Commando Groups. He proposes using them in combination to place troops behind enemy lines and keep them supplied. As each Air Commando Group is activated, a Combat Cargo Group would also be activated alongside.

By April 1944, General Arnold has activated two other Air Commando and Combat Cargo Groups, with the intention of activating two more in the future. The newly formed 2nd and 3rd Air Commando Groups are modeled after the Cochran-Alison original, with each unit consisting of two P-51 Squadrons, one Troop Carrier Squadron specialised in gliders, three Liaison Squadrons, and support organisations including airborne engineers, service groups, airdrome squadrons, and an Air Depot Group common to both Air Commando Groups and Combat Cargo Groups. Colonel Alison is tasked with directing the training of the air commando units and monitoring the activation, organisation, and training of the two additional groups in the future.

General Arnold plans to use the Combat Cargo Group to maintain the logistic lifeline once ground soldiers are deployed in the field. The cargo unit are composed of two parts:

- Airlift forces consisting of four C-47 Squadrons of twenty-five aircraft each. Their primary job is to transport troops and supplies to be used in enemy territory.

- Various service organisations including a special service group for each three Combat Cargo Groups, four airdrome squadrons, and an Aerial Re-supply Depot for packing supplies to be delivered by air.

If all four Air Commando and Combat Cargo organisations were activated, General Arnold’s commitment to retake Burma would have been impressive. He intends to allocate an additional 200 P-51 Mustangs, 464 C-47 Dakotas, 128 CG-4A Waco gliders, 384 L-5 Sentinels, and around 50 UC-64 Norsemen, in addition to the air assets already in the China-Burma-India theater. However, General Arnold’s plan is never fully implemented after Colonel Alison expresses his belief that the British would not invade Central and Southern Burma.

General Arnold confirms this with Colonel Cochran and subsequently visits Sir John Dill, the senior British officer stationed in Washington. Colonel Alison’s evaluation of British intentions is confirmed, and despite General Arnold’s efforts to keep his idea alive by appealing to Admiral Mountbatten, he is unsuccessful. The SEAC staff procrastinates and finally agrees to take only one of the units. General Arnold even offers both the 2nd and 3rd Air Commando Groups to General Stilwell, but the infantry General effectively declines.

In January 1945, the group switches back to P-51 Mustangs (D-models).

The 1st Air Commando Group leaves Burma in October 1945 and is inactivated in New Jersey, in November 1945.