| Page Created |

| June 4th, 2023 |

| Last Updated |

| October 15th, 2023 |

| Country |

|

| Related Operations |

| Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein Unternehmen Greif |

| Special Forces |

| Fallschirmjäger |

| December 17th, 1944 – December 23rd, 1944 |

| Unternhemen Stößer |

| Objectives |

- Take and hold the crossroads at Belle Croix Jalhay N-68 and N-672 until the arrival of the 12. SS-Panzer Division. Both roads were main supply routes, the N-68 Eupen and the N-672 Verviers up to Belle-Croix that leads to either Malmedy or Elsenborn.

| Operational Area |

Malmédy Region, Belgium

| Unit Force |

- Nachtschlachtgruppe 20

- Kampfgruppe von der Heydte

- Nachrichtenzug

- 1. Fallschirmjäger-Kompanie

- 2. Fallschirmjäger-Kompanie

- 3. Fallschirmjäger-Kompanie

- 4. Fallschirmjäger-Kompanie

- 5. schwere Kompanie (with twelve machine guns and four mortars)

- 6. Pionier Kompanie

| Opposing Forces |

- U.S. 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division

- Combat Command B, 3rd Armored Division

| Unternehmen Stößer |

| December 4th, 1944 |

Amid the planning of Unternehmen Wacht Am Rhein, concerns loom large about the potential threat posed by the significant American forces to the north of the 6. Panzer-Armee. Field Marshal Model, responsible for Heeresgruppe B and overseeing the offensive operations of Unternehmen Wacht Am Rhein, envisions a special operation to counter this threat.

Model’s proposal calls for an airborne force to be dropped behind American lines in Belgium’s Krinkelt/Rocherath region. The mission’s objective: to disrupt enemy movements southward, thus securing the northern flank of the 6. Panzer-Armee. This strategic maneuver aims to thwart potential advances by American forces, safeguarding the offensive’s success.

| December 6th, 1944 |

Hitler, despite reservations about airborne operations due to heavy casualties during the Crete invasion, approves the concept but shifts the drop location to Hohes Vennen, north of Malmedy, Belgium. This places the paratroopers deeper within American lines than Model’s original plan. The initial drop area raised concerns, given the presence of the American 20th Infantry Regiment and 99th Infantry Battalion in Krinkelt/Rocherath.

This adjustment aims to position paratroopers beyond the immediate reach of American armored units until a breach can be achieved in the enemy lines.

| December 8th, 1944 |

Heeresgruppe B headquarters quickly revises operation plans. Securing the Fallschirmjäger unit becomes a challenge, but appointing a commander poses no such difficulty. In December 1944, Oberst der Fallschirmtruppe, Freiherr Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte, commands the Fallschirm-Armee Waffenschule Aalten in Aalten, Holland. His experience and leadership make him a natural choice for this critical role.

That same day, Oberst von der Heydte is summoned to headquarters and briefed on the operation by General Student, his superior officer. Hitler’s orders call for a significant offensive with a parachute detachment playing a vital role. Von der Heydte’s task: assemble and lead this specialized force, a Kampfgruppe of Fallschirmjäger comprising 1,000 to 1,200 men for immediate deployment.

During the briefing, von der Heydte is led to believe his mission involves parachuting behind enemy lines to support German troops encircling a bridgehead on the Vistula River in Poland. He’s given the impression that his force must be ready for action by December 13th, 1944, the initial planning date for the offensive. This deliberate misinformation aims to ensure the operation’s security and success.

Despite his desire to use his own regiment, the 6. Fallschirmjäger Regiment, he’s forbidden from doing so, as their movement could alert the Allies. However, out of loyalty to their commander, 150 men from von der Heydte’s regiment defy orders and join him. The II Fallschirm-Korps is instructed to contribute one hundred men from each of its Fallschirmjäger Regiments, but they send individuals considered inexperienced, misfits, or troublemakers.

Because of their unsuitability, Von der Heydte returns 150 men to their units. Only a handful have prior combat jump experience, with just 20 percent of his composite unit qualified for weaponized jumps, necessitating the use of containers.

Oberst von der Heydte can’t resist too strongly against the troops assigned to him, as he’s under scrutiny due to his cousin, Claus Philipp Maria Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg’s central role in the July 20th, 1944, assassination attempt on Hitler.

The troops receive their equipment and minimal jump training, even though many have never attended jump school. They gather 112 worn-out Junkers troop-carrier planes, as the Luftwaffe faces a pilot shortage. Many pilots have never operated Junker 52 aircraft, and half have no combat experience. Joint training for pilots and jumpmasters is absent. Given that this is the first German Fallschirmjäger assault at night and into wooded areas, the preparations are undeniably inadequate and leave much to be desired.

| December 9th, 1944 |

The personnel promised to von der Heydte are ordered to assemble at his designated headquarters in Aalten, the Netherlands. Von der Heydte systematically organizes this improvised force into a streamlined battle group configuration. The newly formed Kampfgruppe comprises four light infantry companies, supplemented by a heavy weapons company, a signal and supply platoon, and a compact group headquarters.

However, as is often the norm in military organizations, von der Heydte did not hold overly optimistic expectations regarding the caliber of soldiers he receives. Instead of the best recruits from the parachute regiments, he finds himself dealing with what he candidly referred to as the “usual deadbeats and troublemakers,” individuals whom battalion commanders traditionally aim to transfer elsewhere on such occasions. He remarks, “Never in my entire military career had I been entrusted with a unit displaying such a lack of fighting spirit. Yet, who willingly relinquishes their finest soldiers to another unit?” Of the contingent that converges in Aalten, fewer than three hundred soldiers possess prior combat jump experience. Encouragingly, approximately 150 of these veterans come from von der Heydte’s former 6. Fallschirmjäger Regiment, an inclusion that he perceived as a welcome boon for the Kampfgruppe.

To address the deficit in combat readiness and morale, von der Heydte strategically introduces roughly 150 dependable volunteers sourced from the Aalten jump school. However, it’s noteworthy that several of these recruits are yet to undertake their inaugural parachute jump. Although the numerical strength on paper might have seemed sufficient for the impending mission, the reality is that the Kampfgruppe is still a far cry from a seasoned and harmoniously functioning combat unit.

Due to the limited timeframe available before the commencement of the offensive, the unit finds itself unable to engage in any meaningful training or rehearsal for their upcoming mission. The condensed schedule barely allows for the organization of the different companies and the distribution of necessary equipment. Complicating matters, a significant portion of the soldiers is recently transferred from Luftwaffe ground elements and lacks even the fundamental skills expected of infantry personnel. Von der Heydte’s company commanders are consistently astonished by the glaring deficiencies in the troops’ knowledge and capabilities.

| December 10th, 1944 |

6. Panzer-Armee, the unit that von der Heydte is tasked to support, is notified by Heeresgruppe B about Unternehmen Stößer.

| December 11th, 1944 |

Oberst von der Heydte reports to 6. Panzer-Armee Headquarters and is provided with detailed mission guidance outlining the true objective of his operation. The orders for Operation Stößer are issued to von der Heydte by SS-Brigadeführer Kraemer, the Army Chief of Staff:

“On the first day of the attack, 6. Panzer-Armee will secure Liege or the bridges across the Meuse south of the city. At dawn on the second day of the attack, Kampfgruppe von der Heydte will conduct a parachute drop into the Baraque Michel area, located eleven kilometers north of Malmédy. The objective is to secure the critical road junction at Baraque Michel for use by the armored units of the 6. Panzer-Armee, potentially elements of the 12. SS-Panzer-Division. If, for technical reasons, this mission cannot be carried out on the morning of the first day of the attack, Kampfgruppe von der Heydte will execute the drop early on the following morning into the Ambleve river or Amay areas to secure the bridges there for the advance of the 6. Panzer-Armee’s armored units.”

The parachute drop was scheduled to commence at 03:00 hours on December 14th, 1944, and was planned as a night jump. To confuse the Americans, three hundred dummy figures would be dropped along with the Fallschirmjäger. Their dropzone was north of Camp Elsenborn. The intention was to make the unit appear larger than it actually was.

Oberst von der Heydte also met SS-Oberstgruppenführer Josef Dietrich, the commander of the 6. Panzer-Armee. During an uncomfortable meeting in which Dietrich was under the influence of alcohol, he repeated the instructions from earlier that day. Von der Heydte was to conduct a dawn jump on the first day, the primary objective being to clear the roads in the Hohes Venn area for the advancing armored spearhead units. These roads led from Elsenborn-Malmédy towards Eupen. Additionally, they were to impede any attempts by Allied forces to intervene. He also informed von der Heydte that German armored reinforcements would reach his location within twenty-four hours. When von der Heydte conferred with his commander, Dietrich’s headquarters could provide neither photographs nor reconnaissance of the drop zones. In order to avoid alerting the Allied forces, the German command devised a plan to carry out the airdrop without conducting prior reconnaissance or taking aerial photographs.

When asked to carry carrier pigeons in case of radio problems, Dietrich replied, “This is an army, not a zoo! If I can run a panzer army without pigeons, then you should be able to lead a Kampfgruppe without them.”

During their meeting, von der Heydte’s inquiry about an estimation of the enemy situation prompted the following response from Dietrich: “I am not a prophet. You will likely discover sooner than I the American forces that will be deployed against you.”

Later that day, von der Heydte made an attempt to gather additional information from 6. Panzer-Armee Headquarters. However, his efforts yielded limited results. He noted: “We had thoroughly reconnoitered the American front lines, and the enemy’s chain of command was well known. Yet,

| December 12th ,1944 |

Oberst von der Heydte pays a visit to the Model’s headquarters of Heeresgruppe B near Bad Münstereifel. Here he attends a high-level gathering held there. During this crucial meeting, the last set of orders were disseminated to the various corps and division commanders involved in the upcoming operations. Model specifically tasked Skorzeny with delivering a briefing to the assembled commanders regarding the intricacies of Operation Greif.

Upon inadvertently becoming privy to the existence of Skorzeny’s Operation Greif, von der Heydte promptly takes measures to ensure a clear demarcation between Skorzeny’s forces and his own men. This decision aims to mitigate the potential for confusion, miscommunication, and even accidental friendly fire between the two separate operations.

Von der Heydte’s request to establish a boundary line between the two units is granted, successfully establishing a clear separation that kept the forces of Operation Greif at a distance from the activities of Unternehmen Stößer. This proactive step ensures that each operation could proceed with its objectives without hindrance or interference from the other.

In addition to securing this boundary, von der Heydte recognises the significance of having effective communication and coordination capabilities on the battlefield. To this end, he requests and is granted a forward observer team from the 12. SS-Panzer-Division. This specialised team is equipped with long-range radios, enabling them to call for crucial fire support from the division’s artillery battery when needed. Furthermore, this observer team would play a crucial role in facilitating the synchronisation and coordination of forces during the operation. The approval of this request is a strategic decision that underscores the importance of well-coordinated communication and support mechanisms for the success of Unternehmen Stößer.

| December 13th, 1944 |

The essential weapons, attire, and equipment are distributed among the different companies. The vital long-range radio sets, crucial for maintaining communication links with 6. Panzer-Armee headquarters and the artillery units of the 12. SS-Panzer-Division are also allocated. Simultaneously, preparations are underway to assemble the necessary parachutes at a camp situated near the departure airfields designated for the upcoming mission. Although the Stößer units encounter minor setbacks such as the denial of backup communication pigeons and the inherent challenge of being a lightweight force, significant equipment-related hurdles are relatively minimal.

That very same day, orders are issued for the Stößer Kampfgruppe to relocate to its designated holding area at Sennelager, Germany. Interestingly, due to heightened security measures, the arrival of the parachutists at the camp seems to have caught the camp personnel off guard, leaving them unprepared to accommodate the group. Consequently, Baron von der Heydte has to resort to enlisting the help of a friendly civilian acquaintance to secure lodging in houses within the nearby village of Verlinghausen. Adding to the logistical complexities, von der Heydte is informed that he will depart from two airfields: Senne I and Senne II. However, the existence of these airfields turns out to be more of a conceptual idea within certain staff planners’ minds, as these facilities are still in the process of being constructed.

During that day, Transportgeschwader 3 of the Luftwaffe, is designated to assist von der Heydte’s operation. The unit has an adequate fleet of Junker52 transport aircraft at their disposal, capable of carrying and deploying nearly the entire kampfgruppe in a single lift. However, there is a notable deficiency in trained pilots. The majority of these pilots are recent graduates from flight school, lacking significant experience. In fact, an overwhelming seventy percent of them are not even certified to operate the Junker52 aircraft. This lack of qualification extends to crucial areas such as formation flying, airborne operations, and particularly night flying and navigation.

Nonetheless, a series of coordinated measures are devised to assist the Luftwaffe pilots in successfully navigating to the designated drop zone. Firstly, a route illuminated by ground searchlights will guide the aircraft from Paderborn and Lippespringe airfield to the frontline, serving as a visual guide for the initial part of the flight. As they approach the frontline, the searchlights will be substituted with tracer fire from anti-aircraft batteries situated along the flanks.

Moreover, the transport planes themselves will deploy flares to illuminate their positions and facilitate the formation of a column. A specialised Ju-88 bomber from Nachtschlachtgruppe 20 is assigned to precede the transport aircraft by a quarter of an hour. This bomber will mark the drop zone with incendiary bombs, providing a clear indication of the target area.

During the final leg of the journey, the transport planes will maintain their navigation lights, ensuring visibility among the formation. Once the drop operation is initiated, they will continue to release flares over the drop zone itself. The strategic combination of these measures aims to overcome the inherent challenges of nighttime aviation and enhance the prospects of an accurate and successful parachute drop.

| December 14th, 1944 |

On this day, Unternehmen Wacht Am Rhein (commonly known as the Battle of the Bulge) and, consequently, Unternehmen Stößer (the parachute operation led by Oberst von der Heydte) are postponed. This delay is primarily due to the failure to assemble the attacking divisions in time for the planned offensive.

| December 15th, 1944 |

Oberst von der Heydte once again pays a visit to the headquarters of Generalfeldmarschall Model’s Heeresgruppe B near Bad Münstereifel. At this point, Model is still asleep, having worked through the night. General Krebs, Model’s Chief of Staff, briefs von der Heydte on the attack plans and objectives. The time of the drop, referred to as “P-hour”, is set for 02:00 on December 16th, 1944.

When von der Heydte expresses serious doubts about the success of a parachute drop, Krebs wakes Model. After von der Heydte relays his report, Generalfeldmarschall Model inquires whether von der Heydte believes the parachute drop had a ten percent chance of success. When von der Heydte confirms this, Model remarks that the entire offensive has no more than a ten percent chance of success. However, he emphasises the necessity of attempting it, as it represents the last remaining opportunity to achieve a favourable outcome for the war.

Generalfeldmarschall Model concludes that if they don’t maximize this ten percent chance, Germany will undoubtedly face certain defeat. This decision underscores the desperation of the situation faced by the German high command during this phase of World War II.

With only 12 hours to issue his orders for the jump, Oberst von der Heydte quickly organises his Fallschirmjäger companies. Afterward, the Fallschirmjäger prepare to embark on trucks that will bring them to Lippespringe and Paderborn Airfields, where the planes for the parachute drop are assembled.

However, a significant logistical setback occurs when the trucks fail to arrive due to a lack of fuel. Another division apparently requisitioned the gasoline intended for the trucks that were supposed to carry the paratroopers to the airfields. This delay results in the rescheduling of the jump for 03:00 on December 17th, 1944.

These logistical challenges and delays further highlight the complexities and difficulties faced by the German forces in executing this operation, as they struggle with limited resources and deteriorating circumstances on the Western Front.

| December 17th, 1944 |

In the early hours, amidst a severe snowstorm, strong winds and thick cloud cover, a total of 109 Ju 52 transport planes carrying approximately 1,000 Fallschirmjäger take off. More than 150 members of the Kampfgruppe are unable to participate in the airdrop due to insufficient transport capacity. The plan for these individuals is to make their way overland and join the Fallschirmjäger after 6. Panzer-Armee has advanced to their location. As the transports cross the Allied lines, they encounter difficulties maintaining formation. Inexperience plays a role, compounded by a strong headwind that many pilots fail to anticipate.

The efforts taken to aid the pilots in identifying the drop zone during nighttime operations has limited effectiveness, particularly for the less-experienced aircrews. Despite the presence of German searchlight batteries situated behind German lines, which provide partial guidance to aircraft, a significant gap of sixty kilometres existed between the last searchlights and the incendiary markers near the designated drop zone. Additionally, the presence of Allied flak intensifies the dispersal of the aircraft formations. This causes several pilots to veer significantly off course.

In an attempt to mark the designated drop zone, a Messerschmitt fighter drops flares a few minutes prior to the scheduled drop time. Unfortunately, only a handful of pilots are able to spot these flares amidst the chaotic conditions.

A Junker88 night-bomber from the Nachtschlachtgruppe 20 is assigned to lead the way as a pathfinder. The aircraft departs by 03:30 hours, by which time the initial lift of aircraft already had completed their drops. Consequently, numerous aircraft encounter challenges in accurately locating the designated drop zone.

However, as a result of the pilot’s inexperience, they end up flying with their navigation lights turned on. The overall lack of training for conducting nighttime drops and flying in formation results in a bad drop.

Numerous planes deviate from their intended course during the operation. It is fair to say that the parachute jump turns out to be a complete disaster. It results in a chaotic situation for the Fallschirmjäger who found themselves scattered all over the Belgian countryside. Instead of landing in their designated drop zone, many of them are dropped kilometres away. The drop zone itself is located in the woods and exacerbated by ground winds of almost a sixty kilometres per hour. Normally, German Fallschirmjäger are only permitted to jump when ground winds were less than 25 kilometres per hour. As a result, the casualty rate during the jump exceeds 10 percent.

A significant portion of the signals platoon mistakenly lands in front of surprised Volksgrenadiers, just south of Monschau. The Fallschirmjäger, are joined by a communications squad of four SS men from the 12. SS-Panzer-Division Hitlerjugend, SS-Panzer Artillerie Regiment 12, 7. Batterie, wearing portable radio equipment and led by SS-Obersturmführer Harald Etterich. They too suffer a major setback, when the only radio set they carry turns out to be damaged beyond repairment after the landing.

Some unfortunate soldiers even end up as far as Holland. Around 250 men land near Bonn, a location approximately eighty kilometres away from the designated drop zone. Another rifle company mistakenly drops behind enemy lines a staggering fifty kilometres away from the designated drop zone. Out of the total of 106 aircraft that participate in the airdrop operation, only thirty-five of them successfully deploy their Fallschirmjäger over the Hohen Venn area, and even fewer reach the intended drop zone. Of these thirty-five aircraft, only ten manage to release their payloads directly on or in close proximity to the originally planned drop zone.

Out of the 1,000 men strong Kampfgruppe that took off on December 17th, 1944, only around 450 soldiers successfully land within the Hohen Venn area. About one hundred of them manage to land near the designated drop zone.

The situation was so dire that some of the Fallschirmjäger, who lost their lives upon landing, remained undiscovered until the arrival of the spring thaw months later. The harsh weather conditions took a toll on the injured, and sadly, some of them die in the following days to exposure.

Due to the widespread scattering of the parachute drop, the Americans observe Fallschirmjäger throughout the Ardennes region. The Allies, mis interpreter the situation, believing that a significant jump involving a division-sized force has occurred. This causes substantial confusion among the American troops. It leads them to allocate resources towards securing their rear areas instead of directly confronting the main German thrust at the front. As a result, the U.S. 18th Infantry Regiment consisting of 3,000 men and an armoured combat command consisting of three hundred tanks and 2,000 men are deployed for several days in search of the presumed German force.

Notably, Colonel von der Heydte, is the first to parachute out of his aircraft, reportedly lands in the correct drop zone. Upon landing, he initially gather only six other paratroopers who have also successfully landed on the designated drop zone. Von der Heydte, still recovering from an accident, had his left arm and shoulder immobilised in a splint. Consequently, he makes the jump using a captured Russian “triangular” parachute. Unlike the German designs, this parachute experienced less oscillation during descent and offers more maneuverability, enabling von der Heydte to select a safer landing spot and minimize further injuries. However, despite his precautions, he ends up injuring his right arm during the jump.

Oberst von der Heydte, leading this small group, heads towards the designated objective area, specifically the Baraque Michel crossroads. By 05:00, approximately twenty-five men have gathered at the objective site. By dawn only a meager number of Fallschirmjäger manage to rendezvous with their commander at the assembly area near the fork in the Eupen road, just north of Monte Rigi. By the morning of the 17th, 1944 von der Heydte has gathered only a company-sized contingent of Fallschirmjäger. Some men of whom being already wounded. A little over ten percent of the Kampfgruppe. With such a limited force available for action, von der Heydte organises a defensive perimeter within the woods. He dispatches small patrols to gather intelligence, sets ambushes for any encountered American units. Searches for their missing weapons containers and tries to locate stragglers.

Due to the challenges of jumping with weapons while using the German RZ parachute, only a small fraction of the men manages to bring their weapons during the jump. This resulted in the loss of most of the weapon containers during the chaotic drop. Consequently, a significant number of Fallschirmjäger found themselves without rifles.

Von der Heydte finds himself isolated, approximately fifteen kilometres away from the German ground forces, but without any means to establish contact with them. In an attempt to establish communication, He dispatches reconnaissance patrols to seek out elements of the 6. SS-Panzer-Armee. Unfortunately, many of these patrols fail to return, and those that do are unable to make successful contact. By the evening of December 17th, 1944, von der Heydte manages to regroup with approximately 150 scattered stragglers under the command of war correspondent Oberleutnant Bruno von Kayser from his composite battalion, but he still lacks a cohesive and effective fighting force.

Furthermore, they are devoid of support weapons, lack fire support, and have no means of radio communication. Given these limitations, von der Heydte decides to maintain a low profile throughout the day while continuing to dispatch small patrols. However, it has become too late to execute the originally planned operation of blocking American reinforcements. Instead, Von der Heydte and his group build a defensive perimeter in the woods 2-3 kilometres Northeast of the crossroads.

Departing from Sennelager Paderborn Airfield, three Ju-52 aircraft take off at 19:00, destined for the Ardennes. It is an attempt to provide the Fallschirmjäger with additional provisions, including food, ammunition, and the 36-man heavy platoon. Regrettably, this operation proves to be unsuccessful as well, yielding limited results.

| December 18th, 2023 |

To prevent detection by American forces, von der Heydte decided to relocate his main body approximately three kilometres north of the crossroads during the early hours, taking cover within the dense forest of the Hertogenwald. Despite suggestions from junior leaders to launch an immediate attack and disrupt the roads with the available forces, von der Heydte choses to persist with reconnaissance and ambush tactics. With a severe shortage of heavy weaponry, a mere quarter of his initial force remaining, and only enough ammunition for a single significant engagement, von der Heydte opts to exercise patience and wait for a more opportune moment.

Therefor the main force of German Fallschirmjäger conceals themselves within the woods. Unable to intervene as the reinforcements they are meant to impede carry on without hindrance.

A group of Fallschirmjäger encounters a nerve-wracking situation. They have to seek refuge in a ditch when a substantial convoy of American vehicles passes by. This convoy happens to be from the American 1st Infantry Division. Fortunately, the Americans mistake the German Fallschirmjäger for fellow Americans. The passing American forces simply wave at the Germans in a friendly manner.

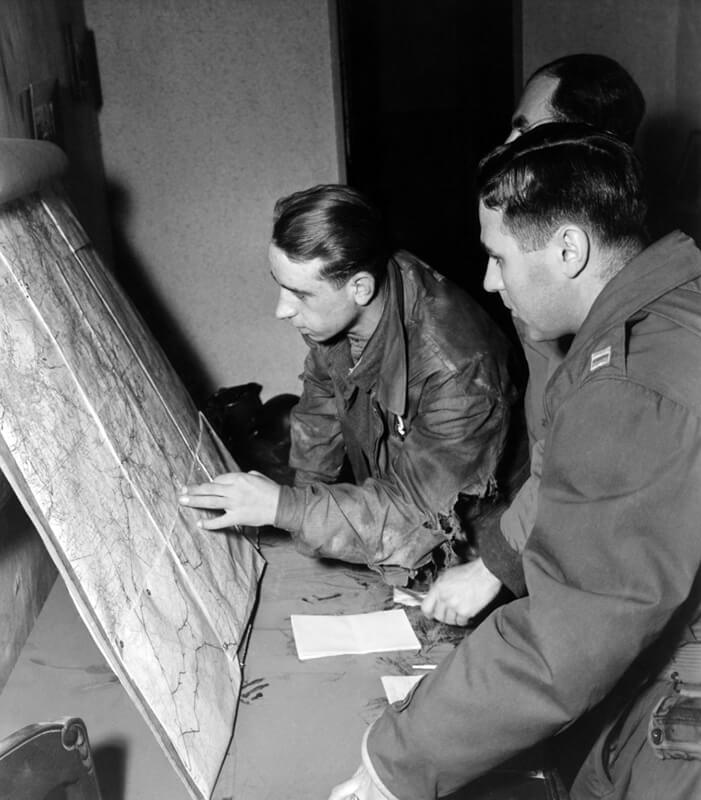

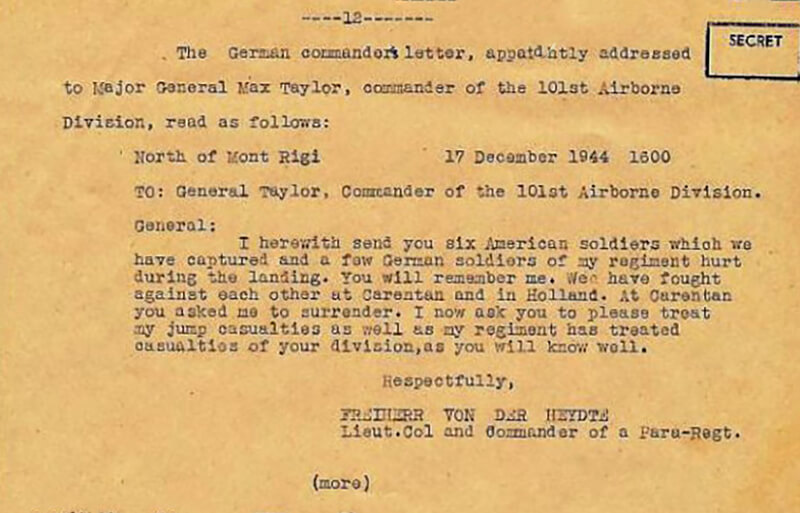

During their patrols, the German forces manage to capture a small number of prisoners, including a motorcycle dispatch rider who happens to be carrying the operational orders for the U.S. Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps. Regrettably, the German troops lack the means to transport or detain the prisoners, so they make the decision to send them back to the American lines alongside with their wounded comrades. Von der Heydte, recognising the name of Major General Maxwell Taylor, commander of the 101st Airborne Division on the papers, personally writes a note to him, appealing for the compassionate care of the wounded Fallschirmjäger.

North of Mont Rigi

To General Taylor commander of the 101st Airborne Division

General:

I herewith send you six American soldiers which we have captured and a few German soldiers from my regiment hurt during the landing. You will remember me. We have fought against each other at Carentan and in Holland. At Carentan you asked us to surrender. I now ask you to please treat my jump casualties as well as my regiment treated casualties of your division, as you will well know.

Respectfully

Freiherr von der Heydte

Oberst and Commander of a Paratroopers Regiment

During the night, a solitary Junker 88 bomber tries to air-drop supplies to the Stoesser force. However, only a few of the “Essenbomben” containers are successfully retrieved, and to the disappointment of the Fallschirmjäger, these containers did not contain any provisions such as food, ammunition, or weapons. The Fallschirmjäger carried only a 24-hour ration and are now starting to experience the effects of wintry weather and the lack of sustenance.

Meanwhile, American patrols persist in their search for von der Heydte’s force, and the scope of the search expand as larger American units join the efforts to locate the German Fallschirmjäger.

| December 19th, 1944 |

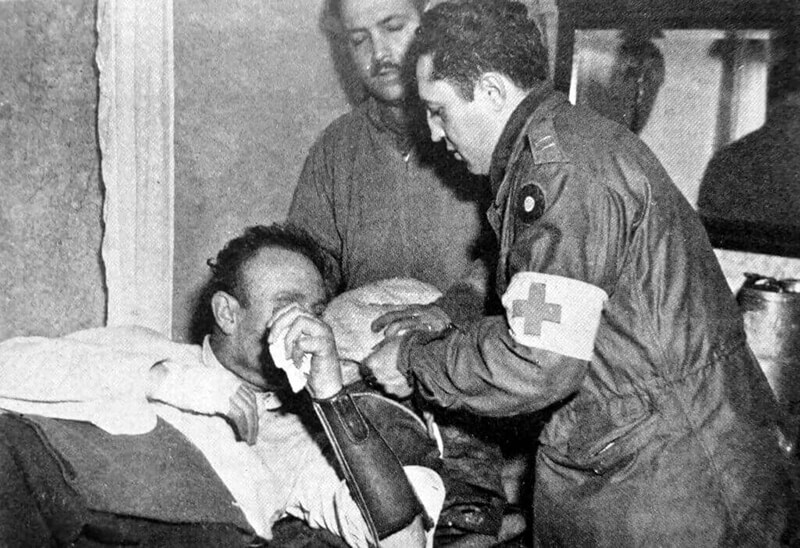

The American forces launch an operation aimed at dislodging von der Heydte’s group located northeast of Mont Rigi. A short but intense exchange of gunfire ensues as the Germans tactically withdraw to the east, resulting in three Fallschirmjägers being wounded. Despite the earnest attempts of the Luftwaffe, their efforts to resupply the Fallschirmjägers with essential provisions such as weapons, ammunition, food, warm clothing, and medical supplies prove to be fruitless. The situation becomes desperate.

During the afternoon, a search party comprising eight soldiers is dispatched to locate the missing parachute food containers. Their efforts lead them to discover two containers. Unfortunately, these containers only contain ammunition without the accompanying weapons, except for a Panzerfaust. Unfortunately, during the search, two of the men are captured, while the remaining members of the search party return empty-handed during the night, without any food.

Subsequently, von der Heydte comes to the realisation that maintaining the cohesion of the Kampfgruppe for more than one, or at most, two days is not feasible. The available ammunition for the machine guns will be depleted after a single engagement. Within a day or two, the soldiers will be severely weakened due to hunger and exposure to cold weather. Initially, his plan is to execute a lone engagement aimed at opening the Eupen-Malmedy road, timed to coincide with the advance of the approaching German armored units toward their position, situated within the 6. SS-Panzer-Armee’s designated attack zone. However, it appears to him that the offensive of the German armored units has become stalled. He makes the decision to deviate from his original mission and instead attempts a breakout to reach the German lines. The planned single engagement will now be fought not to secure the Eupen-Malmedy road but rather to create an opportunity for their movement towards the east, seeking a path to rejoin German forces.

Confronted with the imminent danger of being surrounded, von der Heydte makes the difficult decision to evacuate the wounded and unfit soldiers. He directs them to return to what he believes to be the German front line. In a bid to escape the encirclement imposed by the Allied forces, the remaining fit Fallschirmjägers are assembled and formed into an assault group. Their objective is to break through the encirclement and regain their freedom. Regrettably, despite their determined efforts, the breakout attempts ultimately prove to be unsuccessful, resulting in significant losses and casualties among the Fallschirmjägers.

| December 20th, 1944 |

As the clock struck midnight, the eastward journey leads the group to the Helle River, where they cautiously cross its frigid waters near the confluence of a small stream called Ruisseau de Petit Bonheur. The men wade through the icy waters, intent on advancing beyond the steep riverbank towards Neu Hattlich.

However, their plans are once again thwarted by the presence of American infantry actively searching for them. In the ensuing exchange of gunfire, another Fallschirmjäger is wounded. Faced with uncertainty about the enemy’s strength and position, von der Heydte chooses to disengage and retreat back across the river to establish a defensive position on higher ground for the night. In the early hours, American infantry and armored units begin conducting probing actions to locate von der Heydte’s position.

As the day progresses, with the enemy forces closing in and considering the deteriorating condition of his men, von der Heydte makes the difficult decision to dissolve the battle group. The Fallschirmjäger are instructed to break into small groups of three, employing “escape and evade” tactics to make their way back to German lines. They take advantage of their individual mobility and cover to navigate the challenging terrain and elude the enemy.

| December 21st, 1944 |

As, von der Heydte makes the decision to regroup the surviving Fallschirmjäger into small teams consisting of two to three individuals, he orders them to reach what he believes to be the German lines located in Monschau. Monschau is one of the initial objectives of Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein. The surviving men are instructed to regroup at the Truppenübungsplatz, the training grounds located in Köln-Wahn, Germany. Here, they will receive their long-awaited and well-deserved Christmas furloughs.

Shortly after these final instructions are given, the encampment in the woods is disbanded as advancing American forces press forward into the Königliches Torf Moor, once again firing their weapons. From the east, the sound of approaching tanks from the 3rd Armored Division can be heard along the road connecting Eupen and Monschau. In their haste, some Fallschirmjäger discard their weapons before dispersing into the surrounding woods. The majority of Fallschirmjäger manages to slip away with their weapons and equipment. Like his men, von der Heydte, accompanied by his adjutant and orderly, moves toward Monschau with the belief that it has fallen into German hands, as it was one of the initial objectives of Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein.

To their surprise, Monschau is not under German control. Instead, a U.S. Army engineer battalion has occupied it. Von der Heydte’s physical condition is worsening, burdened by pain in his shattered left forearm and the injury to his right arm sustained during the parachute jump. This is worsened by frostbite and pneumonia. Shivering in anticipation until nightfall, on that evening, von der Heydte summons his adjutant and orderly to go on without him and ventures into town.

At precisely 23:00, he presses the doorbell of a squat two-story house located at Am Oberer Kalk 6, just west of the main road in Monschau. Answering the call, a 56-year-old schoolteacher named Karl Bouschery discovers a frail German officer outside the lattice-work door. Assisting him inside, Bouschery supports von der Heydte’s injured shoulder as they enter the kitchen. Here, the officer promptly collapses onto the wooden floor. The family gathers around him near the comforting glow of the wood stove. Bouschery, having experienced the trenches of World War I himself and harboring disillusionment towards both the war and the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), find a kindred spirit in von der Heydte, who expresses similar sentiments. Overwhelmed by illness and weakened to the point of incapacity, von der Heydte declares, “I’m sick and too weak to fight,” revealing his imminent surrender the following morning.

| December 22nd, 1944 |

Von de Heydte drinks some of the family’s ersatz coffee brewed from wheat berries. His illness prevents him from consuming any solid food. Eugene, Karl’s son, possessing first aid training, improvised a splint for von der Heydte’s fractured fingers using tongue depressors. Despite the town now being under American control, Eugene reveals his affiliation with the Jungvolk. Von der Heydte remains silent and requests pen and paper and writes a letter.

22 December

To the American Commander of the Military Government of Monschau,

Dear Sir,

I tried to meet German soldiers near Monschau. As I could find there no German troops, I surrender because I am hurt and ill and at the end of my physical resources. Please be kind enough to send a doctor and ambulance because I cannot go further. I lie in the bed of Herr Bouschery and await your help and orders.

Yours sincerely,

Freiherr von der Heydte

Obstl Commando of the German Fallschirmjäger troops, region Eupen – Monschau.

With a high fever of 40 degrees Centigrade, the family places von der Heydte on a sofa near the stove, covering him with blankets.

| December 23rd, 1944 |

During the morning, Eugene Bouschery brings the surrender letter to the Hotel Horchem, knowing that some Americans were present there. Captivated by the news, Captain Goetscheus is thrilled to learn that the leader of the German airborne operation is willing to surrender in their town. Goetscheus hurriedly brings the note to the Monschau Postamt, where the headquarters of the 47th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, is situated.

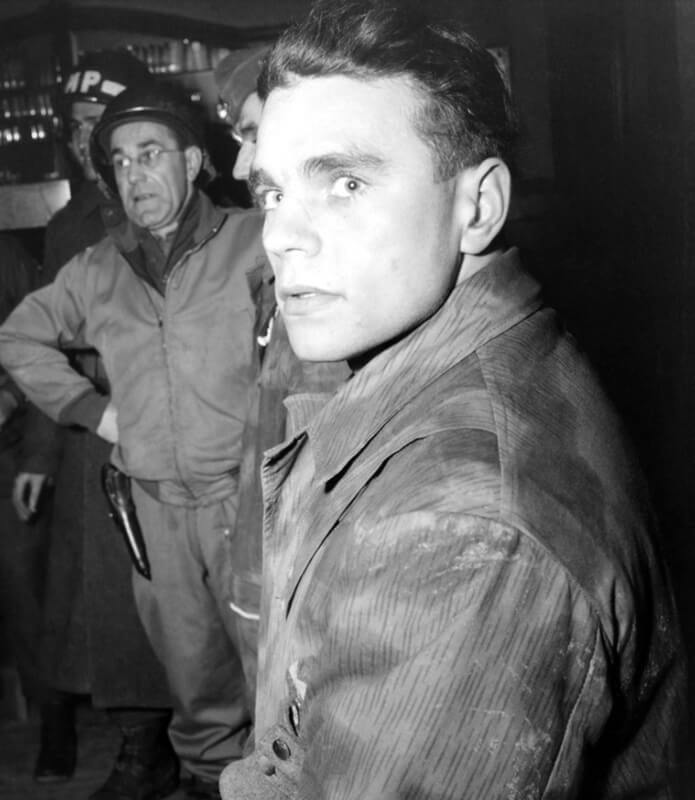

A little later, Lieutenant Colonel Lawrence Q. Langland, Headquarters, 9th Infantry Division, leaves in a jeep with an American doctor, a crewed ambulance, several other jeeps, and a halftrack of heavily armed soldiers. They reach the Bouschery home at 09:00. Langland and the others go in to find von der Heydte hardly a threat. He is extremely ill. Shortly after, being examined by the doctor, he is loaded onto a stretcher, the American soldiers pose with the captured Baron. By 10:00, von der Heydte is on his way to the headquarters of the V Corps in Eupen.

| Remains of December |

Approximately 150 men under von der Heydte’s command successfully manage to escape and reach the German lines, with a significant number finding refuge near Kalterherberg. However, many of them are captured, often handed over to the U.S. Army military government in Monshau by local residents.

| Conclusion |

The operation faced substantial challenges, including adverse weather conditions that caused the dispersion of Fallschirmjäger units across a wide area. Von der Heydte’s troops were further hampered by logistical issues, inadequate supplies, and limited communication capabilities. These difficulties prevented the German paratroopers from effectively accomplishing their mission.

While Kampfgruppe von der Heydte’s mission fails to achieve its primary objective of capturing the crucial crossroads and impeding American reinforcements, it will be inaccurate to categorize Unternhemen Stößer, the final large-scale German airborne operation of the war, as an absolute failure. The mere presence of German Fallschirmjäger infiltrating behind Allied lines induces alarm among both frontline troops and high-ranking commanders. Particularly, the deployment of dummy Fallschirmjäger emerges as one of the operation’s most successful facets. These decoy Fallschirmjäger are strategically placed north of Camp Elsenborn, sowing confusion and bewilderment among American forces. The wide dispersion of the Fallschirmjäger across a vast area during the drop, along with isolated units engaging Allied troops, leads to a significant overestimation of their actual numbers.

The initial impression that an entire division is deployed, rather than a dispersed battalion, had a profound psychological impact on American units stationed in the Ardennes. This perception is further heightened by the presence of SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny’s English-speaking commandos, who operate American jeeps while wearing authentic U.S. uniforms behind enemy lines. The combined effect of these elements, along with the operation’s initial success, leaves a lasting impression on American forces. Reports of enemy Fallschirmjäger lurking in the area triggered numerous alerts in the American rear, diverting their focus from reinforcing the front lines to hunting for German Fallschirmjäger. Consequently, they tie up the American reserve for several days as they diligently scoure for the perceived threat. In this manner, the Fallschirmjäger effectively disrupts the deployment of American troops and manage to delay their reinforcement efforts.

In conclusion, while Operation Stößer did not achieve its primary objectives, it played a crucial role in creating chaos and disruption in the early stages of the Battle of the Bulge or Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein. The mere presence of Fallschirmjäger units infiltrating behind Allied lines and the strategic deployment of decoys had a significant psychological impact on American forces, delaying their reinforcement efforts. This demonstrates the complexity and multifaceted nature of military operations and the importance of psychological warfare in addition to physical engagements.

| Multimedia |

| Photographs |

| Oberst von der Heydte loaded into an Ambulance after being captured. |

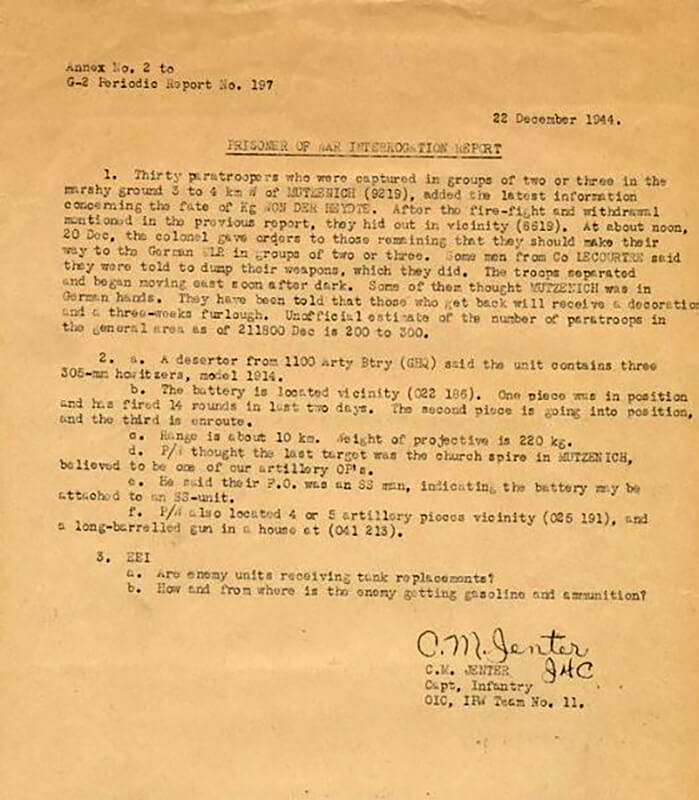

| PW Interrogation Report Oberst von der Heydte |